Soil Moisture Sensing Technologies: Principles, Applications, and Challenges in Agriculture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- Identification: The Scopus database was used to analyse the evolution of research on soil moisture sensors, given its comprehensive and authoritative coverage across disciplines and regions. To minimise publication bias and capture relevant grey literature, targeted Google searches were conducted for technical reports, books, and other non-peer-reviewed sources. All identified records were screened and assessed using the same eligibility and quality criteria applied to peer-reviewed publications.

- Screening: Before analysis, a rigorous data pre-processing procedure was implemented. A combination of keyword filtering and manual screening was used to remove irrelevant records. Relevance was determined by examining titles and abstracts, focusing on studies that address soil moisture sensing in an agricultural irrigation context. The search was restricted to articles and reviews published between 1980 and 2025. The following advanced query was applied: Topic Search = (“soil moisture sensor*” and pubyear > 1979 and pubyear < 2026 and (limit-to (subjarea, “agri”))). The database was queried on 4 June 2025.

- Eligibility assessment: The full texts of the screened records were critically appraised. Studies provides substantive information regarding the operating principles of the technology, its comparative advantages and limitations, and its documented practical applications were included.

- Inclusion and categorisation: Studies meeting the eligibility criteria were systematically classified according to two overarching categories forming the analytical framework of this review, complemented by a third category for general reference:

- a.

- Invasive methods (e.g., dielectric sensors, tensiometers);

- b.

- Non-invasive methods (e.g., ground-penetrating radar, microwave remote sensing, cosmic-ray and neutron sensing);

- c.

- Other general aspects, including references on soil moisture sensing that are not directly attributable to either invasive or non-invasive methodologies.

- Exclusion criteria: Studies were excluded if they focused on primary research outside the agricultural field (e.g., geophysics, engineering, physics and astronomy, mathematics, or social sciences); due to duplication of technological coverage; or because they lacked sufficient technical detail to enable a meaningful critical evaluation.

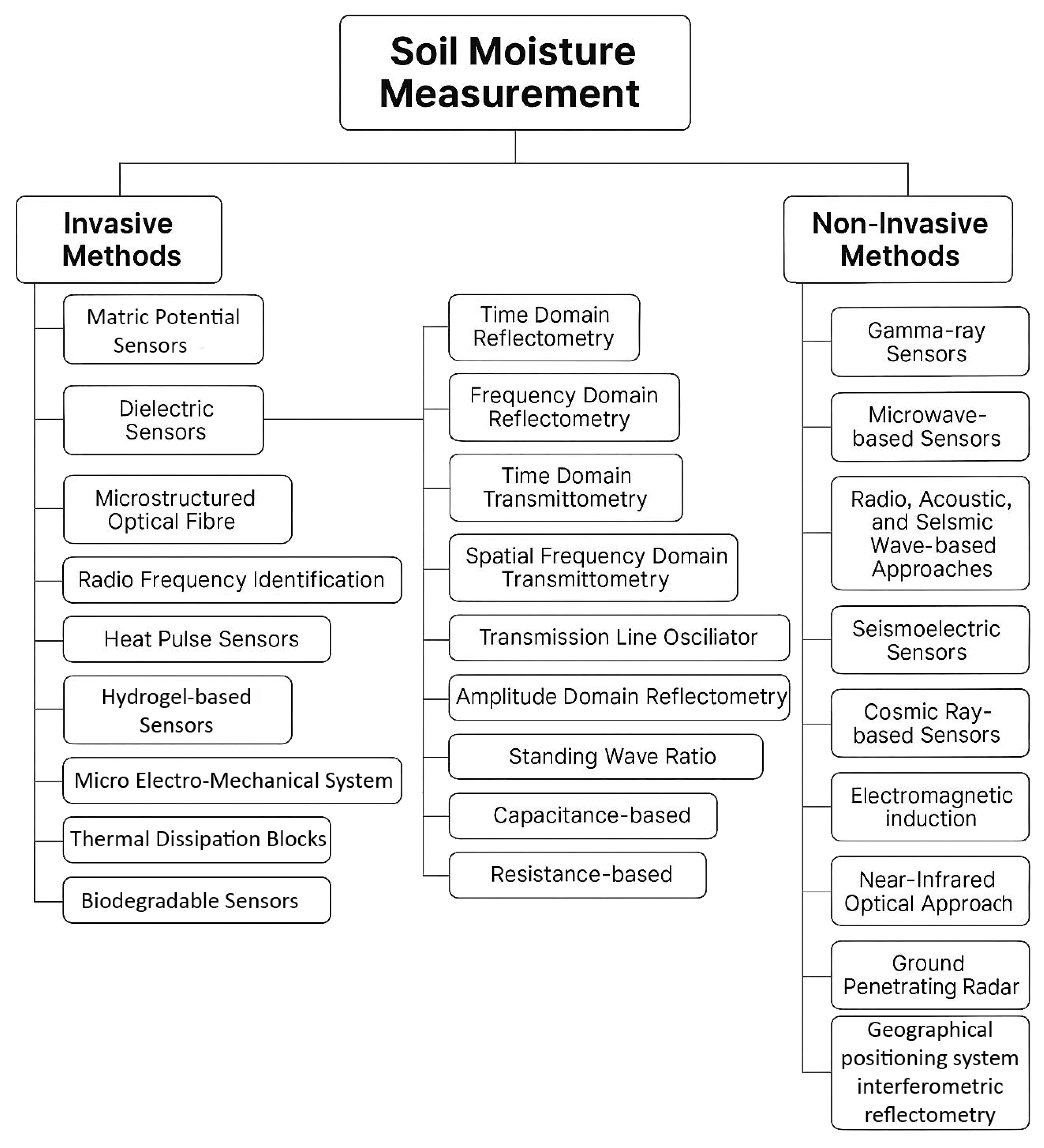

3. Invasive Methods

3.1. Matric Potential Sensors

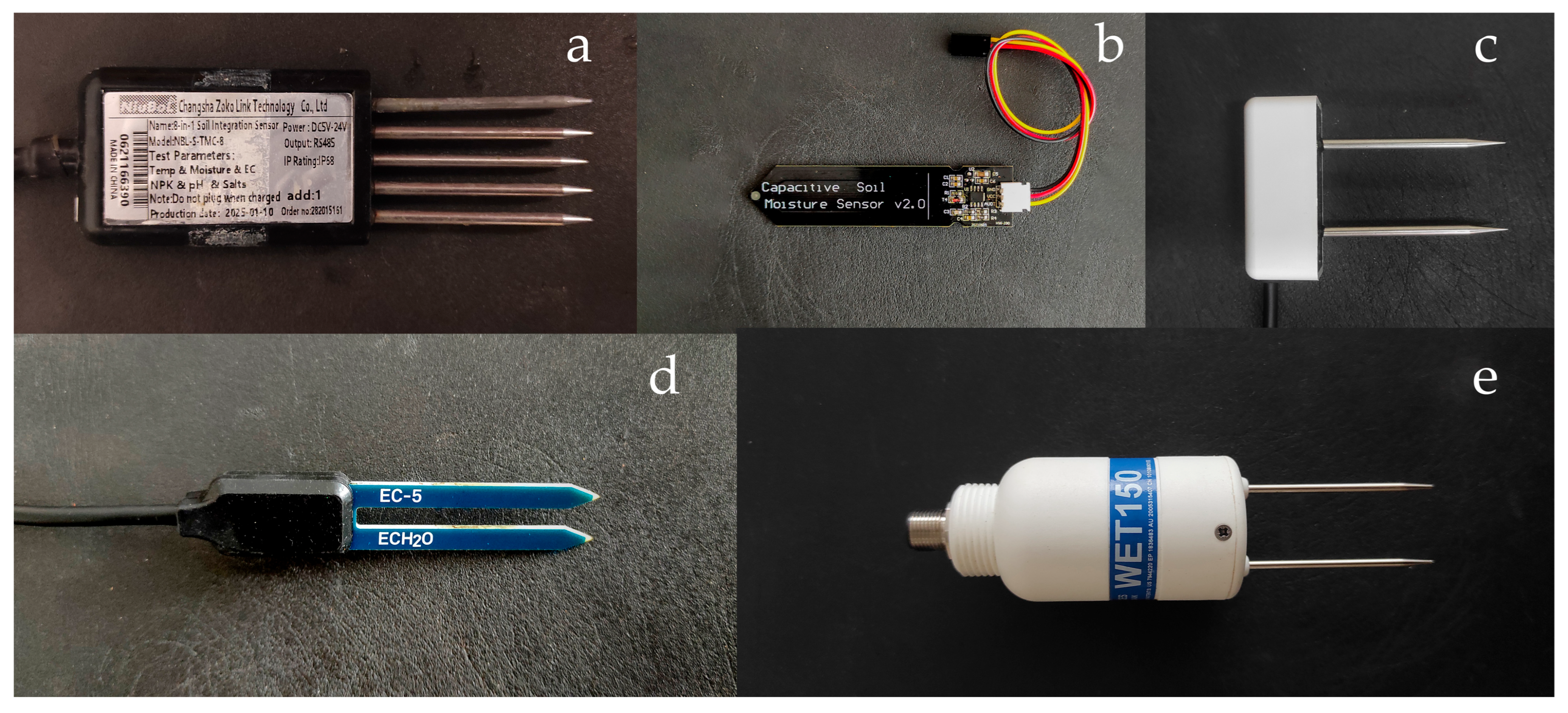

3.2. Dielectric Sensors

3.2.1. Time-Domain Reflectometry

3.2.2. Frequency Domain Reflectometry

3.2.3. Time-Domain Transmittometry

3.2.4. Spatial Frequency-Domain Transmittometry

3.2.5. Transmission Line Oscillator

3.2.6. Amplitude Domain Reflectometry

3.2.7. Standing-Wave Ratio

3.2.8. Capacitance-Based

3.2.9. Resistance-Based

3.3. Microstructured Optical Fibre

3.4. Neutron Probe

3.5. Radio Frequency Identification

3.6. Heat-Pulse Sensors

3.7. Fibre Optic Sensors

3.8. Hydrogel-Based Sensors

3.9. Thermal Dissipation Blocks

3.10. Micro Electro-Mechanical System

3.11. Biodegradable Sensors

4. Non-Invasive Soil Moisture Sensors

4.1. Gamma-Ray Sensors

4.2. Microwave-Based Sensors

4.3. Radio, Acoustic, and Seismic Wave-Based Approaches

4.4. Seismoelectric Sensors

4.5. Cosmic Ray-Based Sensors

4.6. Electromagnetic Induction

4.7. Near-Infrared Optical Approach

4.8. Ground-Penetrating Radar

4.9. Geographical Positioning System Interferometric Reflectometry

5. Critical Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vories, E.; O’Shaughnessy, S.; Sudduth, K.; Evett, S.; Andrade, M.; Drummond, S. Comparison of precision and conventional irrigation management of cotton and impact of soil texture. Precis. Agric. 2021, 22, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwambale, E.; Abagale, F.K.; Anornu, G.K. Smart irrigation monitoring and control strategies for improving water use efficiency in precision agriculture: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Werling, B.; Cao, Z.; Li, G. Implementation of an in-field IoT system for precision irrigation management. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1353597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, Y.K.; Joshi, A.; Panigrahi, R.K.; Pandey, A. Development of a smart irrigation monitoring system employing the wireless sensor network for agricultural water management. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 3224–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Campbell, C.S.; Hopmans, J.W.; Hornbuckle, B.K.; Jones, S.B.; Knight, R.; Ogden, F.; Selker, J.; Wendroth, O. Soil moisture measurement for ecological and hydrological watershed-scale observatories: A review. Vadose Zone J. 2008, 7, 358–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazueta, F.S.; Xin, J.N. Soil moisture sensors. In Florida Cooperative Extension Service. Bulletin; Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1994; Volume 292, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.; Panda, R.K.; Bisht, D.S. Improved generalized calibration of an impedance probe for soil moisture measurement at regional scale using bayesian neural network and soil physical properties. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2021, 26, 04020068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.; Singh, G.; Das, N.N.; Kanungo, A.; Nagpal, N.; Cosh, M.; Dong, Y. Development of low-cost handheld soil moisture sensor for farmers and citizen scientists. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1590662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahage, E.A.A.D.; Nagahage, I.S.P.; Fujino, T. Calibration and validation of a low-cost capacitive moisture sensor to integrate the automated soil moisture monitoring system. Agriculture 2019, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, H.; Huisman, J.A.; Bogena, H.; Vanderborght, J.; Vrugt, J.A.; Hopmans, J.W. On the value of soil moisture measurements in vadose zone hydrology: A review. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W00D06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.L.; Singh, D.N.; Baghini, M.S. A critical review of soil moisture measurement. Measurement 2014, 54, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsner, T.E.; Cosh, M.H.; Cuenca, R.H.; Dorigo, W.A.; Draper, C.S.; Hagimoto, Y.; Kerr, Y.H.; Larson, K.M.; Njoku, E.G.; Small, E.E.; et al. State of the art in large-scale soil moisture monitoring. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 1888–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, M. Review of novel and emerging proximal soil moisture sensors for use in agriculture. Sensors 2020, 20, 6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Gao, W.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Tao, S.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, G. Review of research progress on soil moisture sensor technology. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Han, X.; Jia, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hou, L.; Mei, S. Performance of soil moisture sensors at different salinity levels: Comparative analysis and calibration. Sensors 2024, 24, 6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, R.; Shrestha, D. Assessment of low-cost and higher-end soil moisture sensors across various moisture ranges and soil textures. Sensors 2024, 24, 5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, S.; Montesinos, C.; Campillo, C. Evaluation of different commercial sensors for the development of their automatic irrigation system. Sensors 2024, 24, 7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieberding, F.; Huisman, J.A.; Huebner, C.; Schilling, B.; Weuthen, A.; Bogena, H.R. Evaluation of three soil moisture profile sensors using laboratory and field experiments. Sensors 2023, 23, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustirandi, B.; Inayah, I.; Aminah, N.S.; Budiman, M. Analysis comparison, calibration, and application of low-cost soil moisture in smart agriculture based on internet of things. Telkomnika 2024, 22, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasta, P.; Bogena, H.R.; Sica, B.; Weuthen, A.; Vereecken, H.; Romano, N. Integrating Invasive and Non-invasive Monitoring Sensors to Detect Field-Scale Soil Hydrological Behavior. Front. Water 2020, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.S. Soil water potential measurement: An overview. Irrig. Sci. 1988, 9, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L. Soil moisture tensiometer materials and construction. Soil Sci. 1942, 53, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnett, M.; Bell, J.; Koon, P.A.; Soopramanien, G.; Batchelor, C. The control of drip irrigation of sugarcane using “index” tensiometers: Some comparisons with control by the water budget method. Agric. Water Manag. 1990, 17, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthaler, H.; Vogelsanger, W.; Richard, F.; Wierenga, P. A pressure transducer for field tensiometers. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1983, 47, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalheimer, M. Tensiometer modification for diminishing errors due to the fluctuating inner water column. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.; Buzzi, O. New insight into cavitation mechanisms in high-capacity tensiometers based on high-speed photography. Can. Geotech. J. 2013, 50, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.B.; Kean, J.W. Long-Term Soil-Water Tension Measurements in Semiarid Environments: A Method for Automated Tensiometer Refilling. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take, W.A.; Bolton, M.D. Tensiometer saturation and the reliable measurement of soil suction. Géotechnique 2003, 53, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukes, M.D.; Simonne, E.H.; Davis, W.E.; Studstill, D.W.; Hochmuth, R. Effect of sensor-based high frequency irrigation on bell pepper yield and water use. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Irrigation and Drainage, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–15 May 2003; pp. 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmoneim, A.A.; Khadra, R.; Derardja, B.; Dragonetti, G. Internet of Things (IoT) for soil moisture tensiometer automation. Micromachines 2024, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Silva, S.; Duarte, D.; Pinto, F.C.; Soares, S. Low-Cost LoRaWAN Node for agrointelligence IoT. Electronics 2020, 9, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrov, P.P.; Belyaeva, T.A.; Kroshka, E.S.; Rodionova, O.V. Soil moisture measurement by the dielectric method. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, G.C.; Davis, J.L.; Annan, A.P. Electromagnetic determination of soil water content: Measurements in coaxial transmission lines. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleners, T.J.; Robinson, D.A.; Shouse, P.J.; Ayars, J.E.; Skaggs, T.H. Frequency dependence of the complex permittivity and its impact on dielectric sensor calibration in soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 69, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisso, R.; Alley, M.; Holshouser, D.; Thomason, W. Precision Farming Tools: Soil Electrical Conductivity; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walthert, L.; Schleppi, P. Equations to compensate for the temperature effect on readings from dielectric Decagon MPS-2 and MPS-6 water potential sensors in soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2018, 181, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargas, G.; Soulis, K.X. Performance evaluation of a recently developed soil water content, dielectric permittivity, and bulk electrical conductivity electromagnetic sensor. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, I.A.; Wang, M.; Ren, Y.; Shi, Q.; Malik, M.H.; Tao, S.; Cai, Q.; Gao, W. Performance analysis of dielectric soil moisture sensor. Soil Water Res. 2019, 14, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner-Feldegg, H. Measurement of dielectrics in the time domain. J. Phys. Chem. 1969, 73, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, K.; Tiemann, R. Determination of the complex permittivity from thin-sample time domain reflectometry: Improved analysis of the step response waveform. Adv. Mol. Relax. Interact. Process. 1975, 7, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, G.C.; Davis, J.L. Measurement of soil water content using time-domain reflectrometry (TDR): A field evaluation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaeger, S. A fast TDR-inversion technique for the reconstruction of spatial soil moisture content. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2005, 9, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noborio, K. Measurement of soil moisture content and electrical conductivity by time domain reflectometry: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2001, 31, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, S.; Livingston, N.J.; Hook, W.R. Temperature-dependent measurement errors in time domain reflectometry determinations of soil moisture. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1995, 59, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, W.R.; Livingston, N.J. Errors in converting time domain reflectometry measurements of propagation velocity to estimates of soil moisture content. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1996, 60, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.J.; Young, G.D.; McFarlane, R.A.; Chambers, B.M. The effect of soil electrical conductivity on moisture determination using time-domain reflectometry in sandy soil. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2000, 80, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelbach, H.; Lehner, I.; Seneviratne, S.I. Comparison of four soil moisture sensor types under field conditions in Switzerland. J. Hydrol. 2012, 430–431, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Crespo, J.; van Iersel, M.W. A calibrated time domain transmissometry soil moisture sensor can be used for precise automated irrigation of container-grown plants. HortScience 2011, 46, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, E.; Cannazza, G.; Masciullo, A.; Demitri, C.; Cataldo, A. Reflectometric system for continuous and automated monitoring of irrigation in agriculture. Adv. Agric. 2018, 2018, 2849250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.F.; Conchesqui, M.E.S.; da Silva, M.B. Semiautomatic irrigation management in tomato. Eng. Agríc. 2019, 39, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.; Lipiński, M.; Janik, G. Application of the TDR sensor and the parameters of injection irrigation for the estimation of soil evaporation intensity. Sensors 2021, 21, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comegna, A.; Di Prima, S.; Hassan, S.B.M.; Coppola, A. A novel time domain reflectometry (TDR) system for water content estimation in soils: Development and application. Sensors 2025, 25, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilhorst, M.A.; Breugel, K.V.A.N.; Plumgraaff, D.J.M.H.; Kroese, W.S. Dielectric sensors used in environmental and construction engineering. MRS Proc. 1995, 411, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacheder, M.; Koeniger, F.; Schuhmann, R. New dielectric sensors and sensing techniques for soil and snow moisture measurements. Sensors 2009, 9, 2951–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.B.; Gallardo, M.; Fernández, M.D.; Valdez, L.C.; Martínez-Gaitán, C. Salinity effects on soil moisture measurement made with a capacitance sensor. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woszczyk, A.; Szerement, J.; Lewandowski, A.; Kafarski, M.; Szypłowska, A.; Wilczek, A.; Skierucha, W. An open-ended probe with an antenna for the measurement of the water content in the soil. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 167, 105050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, M.; Hess, A.; Wadzuk, B.M.; Traver, R.G. Quantifying the Impact of Soil Moisture Sensor Measurements in Determining Green Stormwater Infrastructure Performance. Sensors 2025, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyfried, M.S.; Grant, L.E.; Du, E.; Humes, K. Dielectric loss and calibration of the hydra probe soil water sensor. Vadose Zone J. 2005, 4, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houa, X.; Fenga, X.-R.; Jianga, K.; Zhenga, Y.-C.; Liua, J.-T.; Wanga, M. Recent progress in smart electromagnetic interference shielding materials. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 186, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P. Frequency domain versus travel time analyses of TDR waveforms for soil moisture measurement. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A. Soil moisture sensing in saltwater: A review. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Matsuoka, M.; Ariki, T.; Yoshioka, T. Time domain transmission sensor for simultaneously measuring soil water content, electrical conductivity, temperature, and matric potential. Sensors 2023, 23, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, R.; Shariati, N. High-sensitivity and compact time domain soil moisture sensor using dispersive phase shifter for complex permittivity measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 71, 8001010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; Mendez, D.; Avellaneda, D.; Fajardo, A.; Páez-Rueda, C.I. Time-domain transmission sensor system for on-site dielectric permittivity measurements in soil: A compact, low-cost and stand-alone solution. HardwareX 2023, 13, e00398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Oishi, T.; Inoue, M.; Iida, S.; Mihota, N.; Yamada, A.; Shimizu, K.; Inumochi, S.; Inosako, K. Low-Error Soil Moisture Sensor Employing Spatial Frequency Domain Transmissometry. Sensors 2022, 22, 8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kizito, F.; Campbell, C.S.; Campbell, G.S.; Cobos, D.R.; Teare, B.L.; Carter, B.; Hopmans, J.W. Frequency, electrical conductivity and temperature analysis of a low-cost capacitance soil moisture sensor. J. Hydrol. 2008, 352, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleners, T.J.; Soppe, R.W.O.; Robinson, D.A.; Schaap, M.G.; Ayars, J.E.; Skaggs, T.H. Calibration of capacitance probe sensors using electric circuit theory. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Jones, S.B.; Wraith, J.M.; Or, D.; Friedman, S.P. A review of advances in dielectric and electrical conductivity measurement in soils using time domain reflectometry. Vadose Zone J. 2003, 2, 444–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, T.G.; Bongiovanni, T.; Cosh, M.H.; Halley, C.; Young, M.H. Field and laboratory evaluation of the CS655 soil water content sensor. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.; Das, N.; Singh, G.; Cosh, M.; Dong, Y. Advancements in dielectric soil moisture sensor Calibration: A comprehensive review of methods and techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, D.D.; Lakshmi, V.; Jackson, T.J.; Choi, M.; Jacobs, J.M. Large scale measurements of soil moisture for validation of remotely sensed data: Georgia soil moisture experiment of 2003. J. Hydrol. 2006, 323, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleners, T.J.; Verma, A.K. Measured and modeled dielectric properties of soils at 50 megahertz. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilski, B.M.; Granouillac, F.; Claverie, N.; Lemaire, B.; Brut, A.; Tallec, T. Calculation of soil water content using dielectric-permittivity-based sensors—Benefits of soil-specific calibration. Geosci. Instrum. Methods Data Syst. 2023, 12, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittelli, M. Measuring soil water content: A review. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, K.; Nishimura, T.; Kato, M.; Nakagawa, M. Field estimation of soil dry bulk density using amplitude domain reflectometry data. J. Jpn. Soc. Soil Phys. 2004, 97, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroizumi, T.; Sasaki, Y. Estimating the nonaqueous-phase liquid content in saturated sandy soil using amplitude domain reflectometry. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2008, 72, 1520–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, G.J.; Miller, J.D. Measurement of soil water content using a simplified impedance measuring technique. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1996, 63, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatrinon, S.; Chantaweesomboon, W.; Chinrungrueng, J.; Kaemarungsi, K. Moisture sensor based on standing wave ratio for agriculture industry. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology (ECTI-CON), Bangkok, Thailand, 20–22 March 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Shi, Q. Comparison of standing wave ratio, time domain reflectometry and gravimetric method for soil moisture measurements. Sensor Lett. 2011, 9, 1140–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bai, C.; Kuang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wolfgang, P. Performance of three types of soil moisture sensors: SWR, TDR and FD. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2006, 28, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Yu, C.; Xie, T.; Zheng, T.; Sun, M. A Novel Portable Soil Water Sensor Based on Temperature Compensation. J. Sens. 2022, 2022, 1061569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, Y. Determining Forest Duff Water Content Using a Low-Cost Standing Wave Ratio Sensor. Sensors 2018, 18, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Rose, R.L. The electrical properties of soils for alternating currents at radio frequencies. Proc. R. Soc. A. 1933, 140, 359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.M. In situ measurement of moisture in soil and similar substances by ‘fringe’ capacitance. J. Sci. Instrum. 1966, 43, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulraheem, M.I.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Moshood, A.Y.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Taiwo, L.B.; Farooque, A.A.; Hu, J. Recent Advances in Dielectric Properties-Based Soil Water Content Measurements. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; Bell, J.P.; Baty, A.J.B. Soil moisture measurement by an improved capacitance technique, Part I. Sensor design and performance. J. Hydrol. 1987, 93, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, A.; Polyakov, V. Advances in crop water management using capacitive water sensors. Adv. Agron. 2006, 90, 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, F.; Facini, O.; Piana, S.; Rossi Pisa, P. Soil moisture measurements: A comparison of instrumentations performances. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2010, 136, 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüser, M.A.; Pichlhöfer, A.; Korjenic, A. A comparison of capacitive soil moisture sensors in different substrates for use in irrigation systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwamback, D.; Persson, M.; Berndtsson, R.; Bertotto, L.E.; Kobayashi, A.N.A.; Wendland, E.C. Automated Low-Cost Soil Moisture Sensors: Trade-Off between Cost and Accuracy. Sensors 2023, 23, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, Y.K.; Panigrahi, R.K.; Pandey, A. Performance analysis of capacitive soil moisture, temperature sensors and their applications at farmer’s field. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Carpena, R.; Dukes, M.D.; Li, Y.; Klassen, W. Design and field evaluation of a new controller for soil-water based irrigation. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2008, 24, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarezi, R.S.; Dove, S.K.; van Iersel, M.W. An automated system for monitoring soil moisture and controlling irrigation using low-cost open-source microcontrollers. HortTechnology 2015, 25, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoneim, A.A.; Al Kalaany, C.M.; Khadra, R.; Derardja, B.; Dragonetti, G. Calibration of low-cost capacitive soil moisture sensors for irrigation management applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroobosscher, Z.J.; Athelly, A.; Guzmán, S.M. Assessing capacitance soil moisture sensor probes’ ability to sense nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium using volumetric ion content. Front. Agron. 2024, 6, 1346946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedeep, S.; Reshma, A.C.; Singh, D.N. Measuring Soil Electrical Resistivity Using a Resistivity Box and a Resistivity Probe. Geotech. Test. J. 2004, 27, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasantrao, B.M.; Bhaskarrao, P.J.; Mukund, B.A.; Baburao, G.R.; Narayan, P.S. Comparative study of Wenner and Schlumberger electrical resistivity method for groundwater investigation: A case study from Dhule district (M.S.), India. Appl. Water. Sci. 2017, 7, 4321–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, I.R.; Kincaid, D.C.; Wang, D. Operational characteristics of the watermark model 200 soil water potential sensor for irrigation management. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1992, 8, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, N.A.; Reinhart, D.R.; Thomas, P.A.; McCreanor, P.T.; Townsend, T.G. Municipal solid waste in situ moisture content measurement using an electrical resistance sensor. Waste Manag. 2003, 23, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelli, I.; Parri, L.; Bichi, B.; Mugnaini, M.; Vignoli, V.; Fort, A. Low-cost sensors for soil moisture measurement: Modeling and characterization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), Pisa, Italy, 6–8 November 2023; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Adla, S.; Rai, N.K.; Karumanchi, S.H.; Tripathi, S.; Disse, M.; Pande, S. Laboratory calibration and performance evaluation of low-cost capacitive and very low-cost resistive soil moisture sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Sen, S.; Janardhanan, S. Comparative analysis and calibration of low cost resistive and capacitive soil moisture sensor. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.03019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Elhajj, I.H.; Asmar, D.; Bashour, I.; Kidess, S. Experimental evaluation of low-cost resistive soil moisture sensors. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Multidisciplinary Conference on Engineering Technology (IMCET), Beirut, Lebanon, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Aldaba, A.; Lopez-Torres, D.; Campo-Bescós, M.A.; López, J.J.; Yerro, D.; Elosua, C.; Arregui, F.J.; Jean-Louis, A.; Jamier, R.; Roy, P.; et al. Comparative study of capacitive and microstructured optical fiber sensors for soil moisture measurement. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardane, N.S.; Meyer, W.S.; Barrs, H.D. Moisture measurement in a swelling clay soil using neutron moisture meters. Aust. J. Soil Res. 1984, 22, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fityus, S.; Wells, T.; Huang, W. Water content measurement in expansive soils using the neutron probe. Geotech. Test. J. 2011, 34, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, N.J.; Leeds-Harrison, P.B. Some problems associated with the use of the neutron probe in swelling/shrinking clay soils. J. Soil Sci. 1987, 38, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.; Kirkham, D. Determination of soil moisture by neutron scattering. Soil Sci. 1952, 73, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, C.H.M.; Underwood, N.; Swanson, R.W. Soil moisture measurement by neutron moderation. Soil Sci. 1956, 82, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichorim, S.F.; Gomes, N.J.; Batchelor, J.C. Two solutions of soil moisture sensing with RFID for landslide monitoring. Sensors 2018, 18, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada, M.; Lazaro, A.; Villarino, R.; Girbau, D. Battery-less soil moisture measurement system based on a NFC device with energy harvesting. Sensors 2018, 18, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chang, L.; Aggarwal, S.; Abari, O.; Keshav, S. Soil moisture sensing with commodity RFID systems. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Service (MobiSys ′20), Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–19 June 2020; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Carpena, R. Field devices for monitoring soil water content: BUL343/AE266, 7/2004. EDIS 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Dyck, M.; Lv, J. The Heat Pulse Method for Soil Physical Measurements: A Bibliometric Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Horton, R.; Ren, T. Simultaneous determination of soil bulk density and water content: A heat pulse-based method. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanna, J.; Jha, S.; Muruganant, M.; Singh, A.K.; Vyas, A.K.; Kumar, S. Heat pulse probe-based smart soil moisture detection system. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 11428–11436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Shi, B.; Liu, J.; Sun, M.Y.; Fang, K.; Yao, J.; Gu, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.W. Improvement and performance evaluation of a dual-probe heat pulse distributed temperature sensing method used for soil moisture estimation. Sensors 2022, 22, 7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, J.L.; Sauer, T.J.; Horton, R.; Xiao, X. Measuring in situ soil water evaporation with a sensible heat balance approach. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 710–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, M.J.; Ananthasuresh, G.K. Semi-Automated Setup for the Manufacture of Dual-Probe Heat Pulse (DPHP) Soil-Moisture Sensor. In Recent Advances in Industrial Machines and Mechanisms; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, R.S.; Morais, F.O.; França, M.B. Temperature-stable heat pulse driver circuit for low-voltage single supply soil moisture sensors based on junction transistors. Electron. Lett. 2016, 52, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Noborio, K.; Mizoguchi, M.; Kawahara, Y. Matric potential sensor using dual probe heat pulse technique. Agric. Inf. Res. 2017, 26, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamai, T.; Kluitenberg, G.J.; Hopmans, J.W. Design and Numerical Analysis of a Button Heat Pulse Probe for Soil Water Content Measurement. Vadose Zone J. 2009, 8, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorapur, N.; Palaparthy, V.S.; Sarik, S.; John, J.; Baghini, M.S.; Ananthasuresh, G.K. A low-power, low-cost soil-moisture sensor using dual-probe heat-pulse technique. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2015, 233, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, T.L.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V. Fibre-optic sensor technologies for humidity and moisture measurement. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2008, 144, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M.; Principe, S.; Consales, M.; Parente, R.; Laudati, A.; Caliro, S.; Cutolo, A.; Cusano, A. Fiber optic thermo-hygrometers for soil moisture monitoring. Sensors 2017, 17, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Buelga, J.; Sayde, C.; Rodríguez-Sinobas, L.; Selker, J.S. Heated fiber optic distributed temperature sensing: A dual-probe heat-pulse approach. Vadose Zone J. 2014, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidana Gamage, D.N.; Biswas, A.; Strachan, I.B.; Adamchuk, V.I. Soil water measurement using actively heated fiber optics at field scale. Sensors 2018, 18, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.F.; Shi, B.; Wei, G.Q.; Chen, S.E.; Zhu, H.H. An improved distributed sensing method for monitoring soil moisture profile using heated carbon fibers. Measurement 2018, 123, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.F.; Shi, B.; Zhu, H.H.; Tang, C.S.; Song, Z.P.; Wei, G.Q.; Garg, A. Characterization of soil moisture distribution and movement under the influence of watering-dewatering using AHFO and BOTDA technologies. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2019, 25, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-Y.; Shi, B.; Guo, J.-Y.; Zhu, H.-H.; Jiang, H.-T.; Liu, J.; Wei, G.-Q.; Zheng, X. Development and Application of Fiber-Optic Sensing Technology for Monitoring Soil Moisture Field. Front. Sens. 2022, 2, 796789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Agate, S.; Salem, K.S.; Lucia, L.; Pal, L. Hydrogel-based sensor networks: Compositions, properties, and applications—A review. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.Q.; Ran, Z.Q.; Bao, H.Y.; Ye, Q.; Chen, H.; Fu, Q.; Ni, W.; Xu, J.M.; Ma, N.; Tsai, F.C. Intelligent hydrogel on–off controller sensor for irrigation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, G. A self-healing hydrogel electrolyte for flexible solid-state supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 389, 124441. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Lao, J.; Gao, H.; Yu, J. Hydrogels for flexible electronics: Materials, structures, and applications. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 9681–9693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noborio, K.; McInnes, K.J.; Heilman, J.L. Measurements of soil moisture content, heat capacity and thermal conductivity with a single TDR probe. Soil Sci. 1996, 161, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, A.L.; Campbell, G.S.; Ellett, K.M.; Calissendorff, C. Calibration and temperature correction of heat dissipation matric potential sensors. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Ochsner, T.E.; Horton, R.; Ju, Z. Heat-pulse method for soil water content measurement: Influence of the specific heat of the soil solids. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2003, 67, 1631–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.S.; Calissendorff, C.; Williams, J.H. Probe for measuring soil specific heat using a heat-pulse method. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1991, 55, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarara, J.M.; Ham, J.M. Measuring soil water content in the laboratory and field with dual-probe heat-capacity sensors. Agron. J. 1997, 89, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsner, T.E.; Horton, R.; Ren, T. A new perspective on soil thermal properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, K.L.; Kluitenberg, G.J.; Horton, R. Measurement of soil thermal properties with a dual-probe heat-pulse technique. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1994, 58, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, J.L.; Xiao, X.; Horton, R.; Sauer, T.J. Sensible heat measurements indicating depth and magnitude of subsurface soil water evaporation. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W00D05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Mansfield, K.; Saafi, M.; Colman, M.; Romine, P. Measuring soil temperature and moisture using wireless MEMS sensors. Measurement 2008, 41, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, C.; Andonovic, I.; Tachtatzis, C.; Davison, C.; Konka, J. Wireless MEMS sensors for precision farming. In Wireless MEMS Networks and Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Parameswari, P.; Belagalla, N.; Singh, B.V.; Abhishek, G.; Rajesh, G.; Katiyar, D.; Hazarika, B.; Paul, S. Nanotechnology-Based Sensors for Real-Time Monitoring and Assessment of Soil Health and Quality: A Review. Asian J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 10, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusser, S.; Poghossian, A.; Bäcker, M.; Leinhos, M.; Wagner, P.; Schöning, M.J. Characterization of biodegradable polymers with capacitive field-effect sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 187, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, G.A.; Sülzle, J.; Dalla Valle, F.; Cantarella, G.; Robotti, F.; Jokic, P.; Knobelspies, S.; Daus, A.; Büthe, L.; Petti, L.; et al. Biodegradable and highly deformable temperature sensors for the internet of things. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1702390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yu, W.; Rahimi, R.; Ziaie, B. A Biodegradable Sensor Housed in 3D Printed Porous Tube for in-Situ Soil Nitrate Detection. In Proceedings of the Hilton Head Workshop 2018: A Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Workshop, Hilton Head Island, SC, USA, 3–7 June 2018; pp. 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal, S.; Yilma, W.; Sui, Y.; Atreya, M.; Bryan, S.; Davis, V.; Whiting, G.L.; Khosla, R. Degradability of Biodegradable Soil Moisture Sensor Components and Their Effect on Maize (Zea mays L.) Growth. Sensors 2020, 20, 6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, T.; Mizui, A.; Koga, H.; Nogi, M. Wirelessly powered sensing fertilizer for precision and sustainable agriculture. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2024, 8, 2300314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, H.; Huisman, J.A.; Hendricks Franssen, H.J.; Brüggemann, N.; Bogena, H.R.; Kollet, S.; Javaux, M.; van der Kruk, J.; Vanderborght, J. Soil hydrology: Recent methodological advances, challenges, and perspectives. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 2616–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Sadeghi, M.; Jones, S.B.; Montzka, C.; Vereecken, H.; Tuller, M. Ground, proximal, and satellite remote sensing of soil moisture. Rev. Geophys. 2019, 57, 530–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocca, L.; Ciabatta, L.; Massari, C.; Camici, S.; Tarpanelli, A. Soil moisture for hydrological applications: Open questions and new opportunities. Water 2017, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, N. Gamma-ray spectrometry for the measurement of mass attenuation coefficient and bulk density of soil: A review. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2023, 54, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Khan, M.J.; Brodie, G.; Gupta, D.; Pang, A.; Jacob, M.V.; Antunes, E. Measurement and modelling of soil dielectric properties as a function of soil class and moisture content. J. Microw. Power Electromagn. Energy 2020, 54, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardinelli, A.; Luciani, G.; Crescentini, M.; Romani, A.; Tartagni, M.; Ragni, L. Application of non-linear statistical tools to a novel microwave dipole antenna moisture soil sensor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 282, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, S. Microwave technology for moisture measurement. Subsurf. Sens. Technol. Appl. 2000, 1, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.G.D.; Pinto, E.N.M.G.; Neto, V.P.S.; D’assunção, A.G. CSRR-based microwave sensor for dielectric materials characterization applied to soil water content determination. Sensors 2020, 20, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschelli, L.; Berardinelli, A.; Crescentini, M.; Iaccheri, E.; Ragni, L. A non-invasive soil moisture sensing system electronic architecture: A real environment assessment. Sensors 2020, 20, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, F.; Andria, G.; Attivissimo, F.; Giaquinto, N. Soil moisture measurement with acoustic methods. In Proceedings of the 12th IMEKO TC4 International Symposium on Electrical Measurements and Instrumentation, Zagreb, Croatia, 25–27 September 2002; pp. 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo, F.; Andria, G.; Attivissimo, F.; Giaquinto, N. An acoustic method for soil moisture measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2004, 53, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, F.; Attivissimo, F.; Fabbiano, L.; Saving, M. Improvements of seismic sensor design for soil moisture measurement. In Proceedings of the 18th IMEKO World Congress, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 17–22 September 2006; pp. 1740–1745. [Google Scholar]

- Attivissimo, F.; Cannazza, G.; Cataldo, A.; De Benedetto, E.; Fabbiano, L. Enhancement and metrological characterization of an accurate and low-cost method based on seismic wave propagation for soil moisture evaluation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2010, 59, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Vuran, M.C. Impacts of soil moisture on cognitive radio underground networks. In Proceedings of the 1st International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking, Batumi, Georgia, 3–5 July 2013; pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, A. An underground radio wave propagation prediction model for digital agriculture. Information 2019, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, C.; Barnhart, B.; Katti, S.; Winstein, K.; Chandra, R. RF soil moisture sensing via radar backscatter tags. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiv, D.; Allabadi, G.; Kaplan, B.; Kravets, R. smol: Sensing Soil Moisture using LoRa. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2110.01501. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, A.K.; Al-Jumaili, M.; Sut-Lohmann, M.; Durner, W. Wi-Fi signal for soil moisture sensing. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.K.; Do, W.; Hong, J.; Choi, H. A novel and non-invasive approach to evaluating soil moisture without soil disturbances: Contactless ultrasonic system. Sensors 2022, 22, 7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Adams, K.H.; Biondi, E.; Zhan, Z. Fiber-optic seismic sensing of vadose zone soil moisture dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atun, R.; Gürsoy, Ö.; Koşaroğlu, S. Field scale soil moisture estimation with ground penetrating radar and Sentinel 1 data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, J.; Brito, D.; Bordes, C.; Brun, Y.; Guatarbes, B. Experimental quantification of the seismoelectric transfer function and its dependence on conductivity and saturation in loose sand. Geophys. Prospect. 2017, 65, 1097–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyserman, F.I.; Monachesi, L.B.; Jouniaux, L. Dependence of shear wave seismoelectrics on soil textures: A numerical study in the vadose zone. Geophys. J. Int. 2017, 208, 918–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McJannet, D.; Hawdon, A.; Baker, B.; Renzullo, L.; Searle, R. Multiscale soil moisture estimates using static and roving cosmic-ray soil moisture sensors. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 6049–6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreda, M.; Desilets, D.; Ferré, T.P.A.; Scott, R.L. Measuring soil moisture content non-invasively at intermediate spatial scale using cosmic-ray neutrons. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L21402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, H.S.; Brown, P.; Best, T. A systematic literature review of the factors affecting the precision agriculture adoption process. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 1292–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, I.; Phadikar, S.; Majumder, K. State-of-the-art technologies in precision agriculture: A systematic review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4878–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova-Petrova, K.; Geris, J.; Wilkinson, M.E.; Rosolem, R.; Verrot, L.; Lilly, A.; Soulsby, C. Opportunities and challenges in using catchment-scale storage estimates from cosmic ray neutron sensors for rainfall-runoff modelling. J. Hydrol. 2020, 586, 124878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, R.; Evans, J.G.; Battilani, A.; Solimando, D. The Cosmic-ray Soil Moisture Observation System (Cosmos) for estimating the crop water requirement: New approach. Irrig. Drain. 2017, 66, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, W.; Shi, Y.; Liu, W.; Lu, Y.; Pang, Z.; Chen, X. Application of cosmic-ray neutron sensor method to calculate field water use efficiency. Water 2022, 14, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, C.; Pisinaras, V.; Köhli, M.; Dombrowski, O.; Hendricks Franssen, H.-J.; Babakos, K.; Anna Chatzi, A.; Panagopoulos, A.; Bogena, H.R. Monitoring irrigation in small orchards with cosmic-ray neutron sensors. Sensors 2023, 23, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Using Cosmic Rays to Measure Moisture Levels in Soil; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, J.A.; Sudduth, K.A.; Kitchen, N.R.; Indorante, S.J. Estimating depths to claypans using electromagnetic induction methods. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1994, 49, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, D.J.; Freeland, R.S.; Ammons, J.T.; Yoder, R.E. Soil investigations using electromagnetic induction and ground-penetrating radar in southwest Tennessee. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.A.; Bramley, R.G.V.; Gobbett, D.L. Proximal soil sensing for Precision Agriculture: Simultaneous use of electromagnetic induction and gamma radiometrics in contrasting soils. Geoderma 2015, 243–244, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, E.; Werban, U.; Zacharias, S.; Pohle, M.; Dietrich, P.; Wollschläger, U. Repeated electromagnetic induction measurements for mapping soil moisture at the field scale: Validation with data from a wireless soil moisture monitoring network. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altdorff, D.; Galagedara, L.; Nadeem, M.; Cheema, M.; Unc, A. Effect of agronomic treatments on the accuracy of soil moisture mapping by electromagnetic induction. Catena 2018, 164, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.N.; Lamb, D.W.; Falzon, G.; Schneider, D.A. Apparent electrical conductivity (ECa) as a surrogate for neutron probe counts to measure soil moisture content in heavy clay soils (Vertosols). Soil Res. 2014, 52, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Estimation of vegetation water content and photosynthetic tissue area from spectral reflectance: A comparison of indices based on liquid water and chlorophyll absorption features. Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 84, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitel, J.U.H.; Gessler, P.E.; Smith, A.M.S.; Robberecht, R. Suitability of existing and novel spectral indices to remotely detect water stress in Populus spp. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 229, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Kooistra, L.; Schaepman, M.E. Using spectral information from the NIR water absorption features for the retrieval of canopy water content. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2008, 10, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessi, R.S.; Prunty, L. Soil water determination using fiber optics. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1986, 50, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleita, A.L.; Tian, L.F.; Hirschi, M.C. Relationship between soil moisture content and soil surface reflectance. Trans. ASAE 2005, 48, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, C.; Metzger, K.; Debaene, G.; Stenberg, B.; Götzinger, S.; Borůvka, L.; Sandén, T.; Bragazza, L.; Liebisch, F. In-field soil spectroscopy in Vis–NIR range for fast and reliable soil analysis: A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakkala Manage, L.P.; Humlekrog Greve, M.; Knadel, M.; Moldrup, P.; De Jonge, L.W.; Katuwal, S. Visible-near-infrared spectroscopy prediction of soil characteristics as affected by soil-water content. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 82, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Lei, T.; Yan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Dong, Y. A near-infrared reflectance sensor for soil surface moisture measurement. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 99, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Maleki, M.R.; Cockx, L.; Van Meirvenne, M.; Van Holm, L.H.J.; Merckx, R.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Ramon, H. Optimum three-point linkage set up for improving the quality of soil spectra and the accuracy of soil phosphorus measured using an on-line visible and near infrared sensor. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 103, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, Y.; Kuang, B.; Mouazen, A.M. Potential of on-line visible and near infrared spectroscopy for measurement of pH for deriving variable rate lime recommendations. Sensors 2013, 13, 10177–10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, A.; Welp, G.; Damerow, L.; Berg, T.; Amelung, W.; Pätzold, S. Towards on-the-go field assessment of soil organic carbon using Vis-NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy: Developing and testing a novel tractor-driven measuring chamber. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 145, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajícová, K.; Chuman, T. Application of ground penetrating radar methods in soil studies: A review. Geoderma 2019, 343, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirana, S.; Lambot, S.; Krishnapillai, M.; Cheema, M.; Smeaton, C.; Galagedara, L. Ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic induction: Challenges and opportunities in agriculture. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzsche, A.; Jonard, F.; Looms, M.C.; van der Kruk, J.; Huisman, J.A. Measuring soil water content with ground penetrating radar: A decade of progress. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambot, S.; Slob, E.; Minet, J.; Jadoon, K.Z.; Vanclooster, M.; Vereecken, H. Full-waveform modelling and inversion of ground-penetrating radar data for non-invasive characterisation of soil hydrogeophysical properties. In Proximal Soil Sensing; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, H.; Huisman, J.A.; Pachepsky, Y.; Montzka, C.; van der Kruk, J.; Bogena, H.; Weihermüller, L.; Herbst, M.; Martinez, G.; Vanderborght, J. On the spatio-temporal dynamics of soil moisture at the field scale. J. Hydrol. 2014, 516, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, T.; Yu, P.; Zhang, C. Parameter measurement of soil moisture based on GNSS-R signals. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), Dalian, China, 29–31 March 2019; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Desesquelles, H.; Cockenpot, R.; Guyard, L.; Cuisiniez, V.; Lambot, S. Ground-penetrating radar full-wave inversion for soil moisture mapping in trench-hill potato fields for precise irrigation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokossi, K.; Calabia, A.; Jin, S.; Molina, I. GNSS-Reflectometry and Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture: A Review of Measurement Techniques, Methods, and Applications. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K.M.; Small, E.E.; Gutmann, E.; Bilich, A.; Braun, J.; Zavorotny, V. Use of GPS receivers as a soil moisture network for water cycle studies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L24405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Calvet, J.C.; Darrozes, J.; Roussel, N.; Frappart, F.; Bouhours, G. Deriving surface soil moisture from reflected GNSS signal observations from a grassland site in southwestern France. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, C.C.; Small, E.E.; Larson, K.M.; Zavorotny, V.U. Vegetation sensing using GPS-interferometric reflectometry: Theoretical effects of canopy parameters on signal-to-noise ratio data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 53, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Kameyama, K.; Nishiya, M. Effect of sensor installation on the accurate measurement of soil water content. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2017, 68, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.C.; Xu, Z.H.; Ross, D.; Dignan, J.; Fan, Y.Z.; Huang, Y.K.; Wang, G.; Bagtzoglou, A.C.; Lei, Y.; Li, B. Towards water-saving irrigation methodology: Field test of soil moisture profiling using flat thin mm-sized soil moisture sensors (MSMSs). Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 298, 126857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, A.B.; Barnard, D.M.; Chapman, P.L.; Bauerle, W.L. Optimizing substrate moisture measurements in containerized nurseries. HortScience 2012, 47, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauerle, T.L.; Bauerle, W.L.; Goebel, M.; Barnard, D.M. Root system distribution influences substrate moisture measurements in containerized ornamental tree species. HortTechnology 2013, 23, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, J.; Conejero, W.; Mira-García, A.B.; Conesa, M.R.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C. Towards irrigation automation based on dielectric soil sensors. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, M.W.; Chappell, M.; Lea-Cox, J.D. Sensors for Improved Efficiency of Irrigation in Greenhouse and Nursery Production. HortTechnology 2013, 23, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starry, O. The Comparative Effects of Three SEDUM Species on Green Roof Stormwater Retention. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfried, M.S.; Grant, L.E. Temperature effects on soil dielectric properties measured at 50 MHz. Vadose Zone J. 2007, 6, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evett, S.R.; Tolk, J.A.; Howell, T.A. Soil profile water content determination: Sensor accuracy, axial response, calibration, temperature dependence, and precision. Vadose Zone J. 2006, 5, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaparthy, V.S.; Baghini, M.S.; Singh, D.N. Compensation of temperature effects for in-situ soil moisture measurement by DPHP sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaparthy, V.S.; Baghini, M.S.; Singh, D.N. Review of polymer-based sensors for agriculture-related applications. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2013, 2, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Fujimaki, H.; Inoue, M. Calibration and simultaneous monitoring of soil water content and salinity with capacitance and four-electrode probes. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 4, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogena, H.R.; Huisman, J.A.; Oberdörster, C.; Vereecken, H. Evaluation of a low-cost soil water content sensor for wireless network applications. J. Hydrol. 2007, 344, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orangi, A.; Narsilio, G.A.; Ryu, D. A laboratory study on non-invasive soil water content estimation using capacitive based sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martinort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s Optical High-Resolution Mission for GMES Operational Services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, B.; Eash, N.; Freeland, R.; Martinez, L.; Wishart, D. Effective and efficient agricultural drainage pipe mapping with UAS thermal infrared imagery: A case study. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 229, 105930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonard, F.; Weihermüller, L.; Schwank, M.; Jadoon, K.Z.; Vereecken, H.; Lambot, S. Estimation of hydraulic properties of a sandy soil using ground-based active and passive microwave remote sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 53, 3095–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.G.; Ward, H.C.; Blake, J.R.; Hewitt, E.J.; Morrison, R.; Fry, M.; Ball, L.A.; Doughty, L.C.; Libre, J.W.; Hitt, O.E.; et al. Soil water content in southern England derived from a cosmic-ray soil moisture observing system—COSMOS-UK. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrön, M.; Köhli, M.; Scheiffele, L.; Iwema, J.; Bogena, H.R.; Lv, L.; Martini, E.; Baroni, G.; Rosolem, R.; Weimar, J.; et al. Improving calibration and validation of cosmic-ray neutron sensors in the light of spatial sensitivity. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 5009–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, H.; Schnepf, A.; Hopmans, J.; Javaux, M.; Or, D.; Roose, T.; Vanderborght, J.; Young, M.; Amelung, W.; Aitkenhead, M.; et al. Modeling soil processes: Review, key challenges, and new perspectives. Vadose Zone J. 2016, 15, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, D.; Montemurro, F.; Diacono, M. Mapping an agricultural field experiment by electromagnetic induction and ground penetrating radar to improve soil water content estimation. Agronomy 2019, 9, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolittle, J.A.; Brevik, E.C. The use of electromagnetic induction techniques in soils studies. Geoderma 2014, 223–225, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouniaux, L.; Zyserman, F. A review on electrokinetically induced seismo-electrics, electro-seismics, and seismo-magnetics for Earth sciences. Solid Earth 2016, 7, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibertoni, G.; Lenzini, N.; Ferrari, L.; Rovati, L. Design and performance of a near-infrared spectroscopy measurement system for in-field alfalfa moisture measurement. Photonics 2022, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukal, M.S.; Irmak, S.; Sharma, K. Development and Application of a Performance and Operational Feasibility Guide to Facilitate Adoption of Soil Moisture Sensors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method/Approach | Salinity Sensitivity | Temperature Sensitivity | Soil Type Sensitivity | Installation Sensitivity | Calibration Need | Output Temporal Resolution | IoT Suitability | Power Request | Expertise Request | User-Friendliness | Accuracy | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensiometers | ** (1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | ** |

| Time-domain reflectometry | * | * | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | **** | **** | ** | **** | **** |

| Frequency-domain reflectometry | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Time-domain transmittometry | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Frequency-domain transmittometry | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Amplitude-domain reflectometry | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Standing-wave ratio | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Capacitance-based sensors | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | ** | ** | **** | *** | ** |

| Resistance-based sensors | **** | *** | *** | **** | **** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | ** | * |

| Microstructured optical fiber | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | **** | *** | **** | **** | ** | **** | **** |

| Neutron probe sensors | * | ** | ** | **** | **** | ** | * | **** | **** | ** | **** | **** |

| RFID sensors | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** | *** | ** |

| Heat-pulse sensors | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Fiber optic sensors | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | **** | *** | **** | **** | ** | **** | **** |

| Spatial frequency domain transmittometry | *** | ** | *** | *** | ** | **** | **** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| Transmission line oscillator | *** | ** | *** | *** | ** | **** | **** | ** | ** | ** | *** | ** |

| Hydrogel-Based Sensors | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | **** | *** | ** |

| Thermal Dissipation Block | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| MEMS | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** | *** | *** |

| Biodegradable Sensors | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | **** | ** | ** |

| Method/Approach | Salinity Sensitivity | Temperature Sensitivity | Soil Type Sensitivity | Vegetation Cover Sensitivity | Calibration Need | Real-Time Data | IoT Suitability | Power Request | Expertise Request | User-Friendliness | Accuracy | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma-ray sensors | * (1) | ** | ** | ** | **** | ** | * | **** | **** | ** | **** | **** |

| Microwave-based sensors | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | **** | *** | ** | *** | **** |

| Acoustic, seismic, wave-based approaches | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** |

| Seismoelectric sensors | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** |

| Cosmic ray-based sensors | * | ** | ** | *** | *** | **** | ** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** |

| EMI approach | *** | ** | *** | ** | *** | **** | *** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** |

| Near-infrared optical sensors | ** | *** | *** | *** | *** | **** | *** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** |

| Ground penetrating radar | ** | ** | *** | *** | *** | **** | ** | **** | **** | ** | *** | **** |

| GPS sensors | * | * | * | * | * | *** | **** | ** | ** | **** | ** | ** |

| Sensor Type | Technical Maturity (a/b/c) |

|---|---|

| Matric Potential Sensors | a |

| Time-Domain Reflectometry | a |

| Frequency-Domain Reflectometry | a |

| Time-Domain Transmittometry | a |

| Spatial Frequency-Domain Transmittometry | b |

| Transmission Line Oscillator | b |

| Amplitude-Domain Reflectometry | b |

| Standing-Wave Ratio | b |

| Capacitance-based | a |

| Resistance-based | a |

| Microstructured Optical Fibre | b |

| Neutron Probe | a |

| Radio Frequency Identification | b |

| Heat-Pulse Sensors | b |

| Fibre Optic Sensors | b |

| Hydrogel-based Sensors | b |

| Thermal Dissipation Blocks | b |

| Biodegradable Sensors | c |

| Gamma-ray Sensors | b |

| Microwave-based Sensors | a |

| Radio/Acoustic/Seismic Wave Approaches | b |

| Seismoelectric Sensors | b |

| Cosmic Ray-based Sensors | a |

| Electromagnetic Induction | a |

| Near-Infrared Optical Approach | b |

| Ground-Penetrating Radar | b |

| Geographical Positioning Systems (GNSS-R) | c |

| Operational Feasibility (O.F.) Scores | Performance Accuracy (P.A.) Scores | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor | 1 a | 2 b | 3 c (Non-TM) | 3 c (TM e) | 4 d | Silt Loam V f | Silt Loam H g | Loamy Sand V | Loamy Sand H | ||||

| F.C. h | S.S.C. i | F.C. | S.S.C. | F.C. | S.S.C. | F.C. | S.S.C. | ||||||

| CS655 | 100 | 38 | 0 | 52 | 0 | 100 | 76 | 73 | 47 | 90 | 66 | 100 | 53 |

| CS616 | 100 | 84 | 6 | 56 | 0 | 87 | 80 | 0 | 31 | 94 | 74 | 95 | 79 |

| SM150 | 100 | 37 | 26 | 0 | 100 | 74 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 85 | 0 | 98 | 0 |

| 10HS | 100 | 95 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 44 | 84 | 95 | 2 | 87 | 100 | 41 | 8 |

| EC-5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 75 | 73 | N/A j | 84 | 17 | 65 | 84 |

| 5TE | 100 | 40 | 92 | 95 | 100 | 97 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 11 | 91 | 100 |

| TEROS 21 | 100 | 40 | 92 | 95 | 50 | 67 | 80 | 85 | 72 | 0 | 23 | 0 | N/A |

| JD Probe | 100 | 58 | N/A | 60 | 100 | 99 | 0 | N/A | N/A | 100 | 81 | N/A | N/A |

| TDR315L | 0 | 0 | 96 | N/A | 100 | N/A | N/A | 98 | 83 | N/A | N/A | 97 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loconsole, D.; Elia, M.; Conversa, G.; De Lucia, B.; Cristiano, G.; Elia, A. Soil Moisture Sensing Technologies: Principles, Applications, and Challenges in Agriculture. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122788

Loconsole D, Elia M, Conversa G, De Lucia B, Cristiano G, Elia A. Soil Moisture Sensing Technologies: Principles, Applications, and Challenges in Agriculture. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122788

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoconsole, Danilo, Michele Elia, Giulia Conversa, Barbara De Lucia, Giuseppe Cristiano, and Antonio Elia. 2025. "Soil Moisture Sensing Technologies: Principles, Applications, and Challenges in Agriculture" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122788

APA StyleLoconsole, D., Elia, M., Conversa, G., De Lucia, B., Cristiano, G., & Elia, A. (2025). Soil Moisture Sensing Technologies: Principles, Applications, and Challenges in Agriculture. Agronomy, 15(12), 2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122788