Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Fungal Community Diversity in Saline–Alkali Soil Cultivated with Oil Sunflowers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Collection and Processing

2.4. Measurement Items and Methods

2.4.1. Determination of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.4.2. High-Throughput Sequencing of Soil Fungi

- number of OTUs containing one sequence; number of OTUs containing “abund” or fewer sequences; number of OTUs containing more than “abund” sequences

- estimated number of OTUs; observed number of OTUs; number of OTUs containing only one sequence; number of OTUs containing only two sequences

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

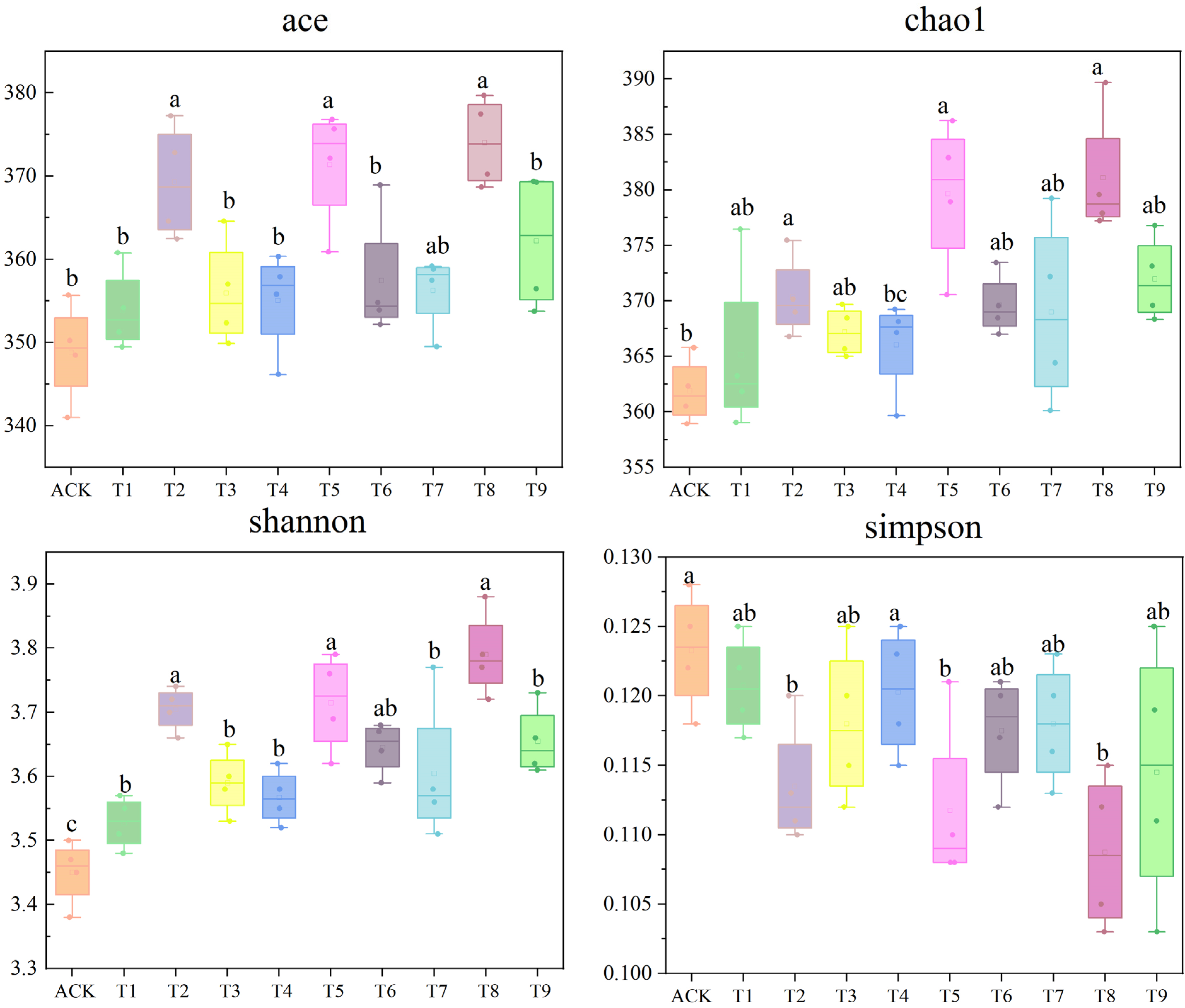

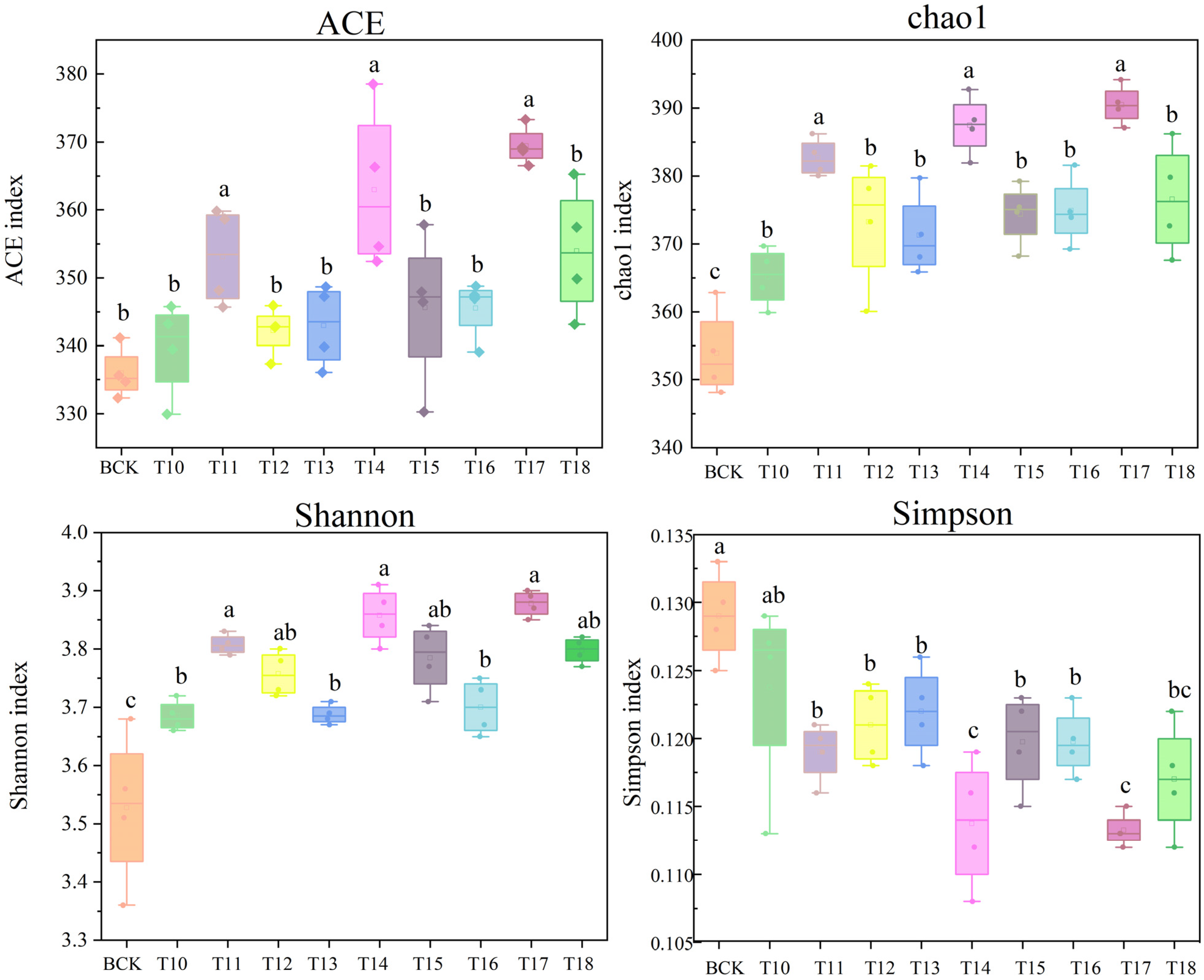

3.1. Effects of Different Microbial Fertilizers on the Diversity of Sunflower Rhizosphere Soil Fungal Communities

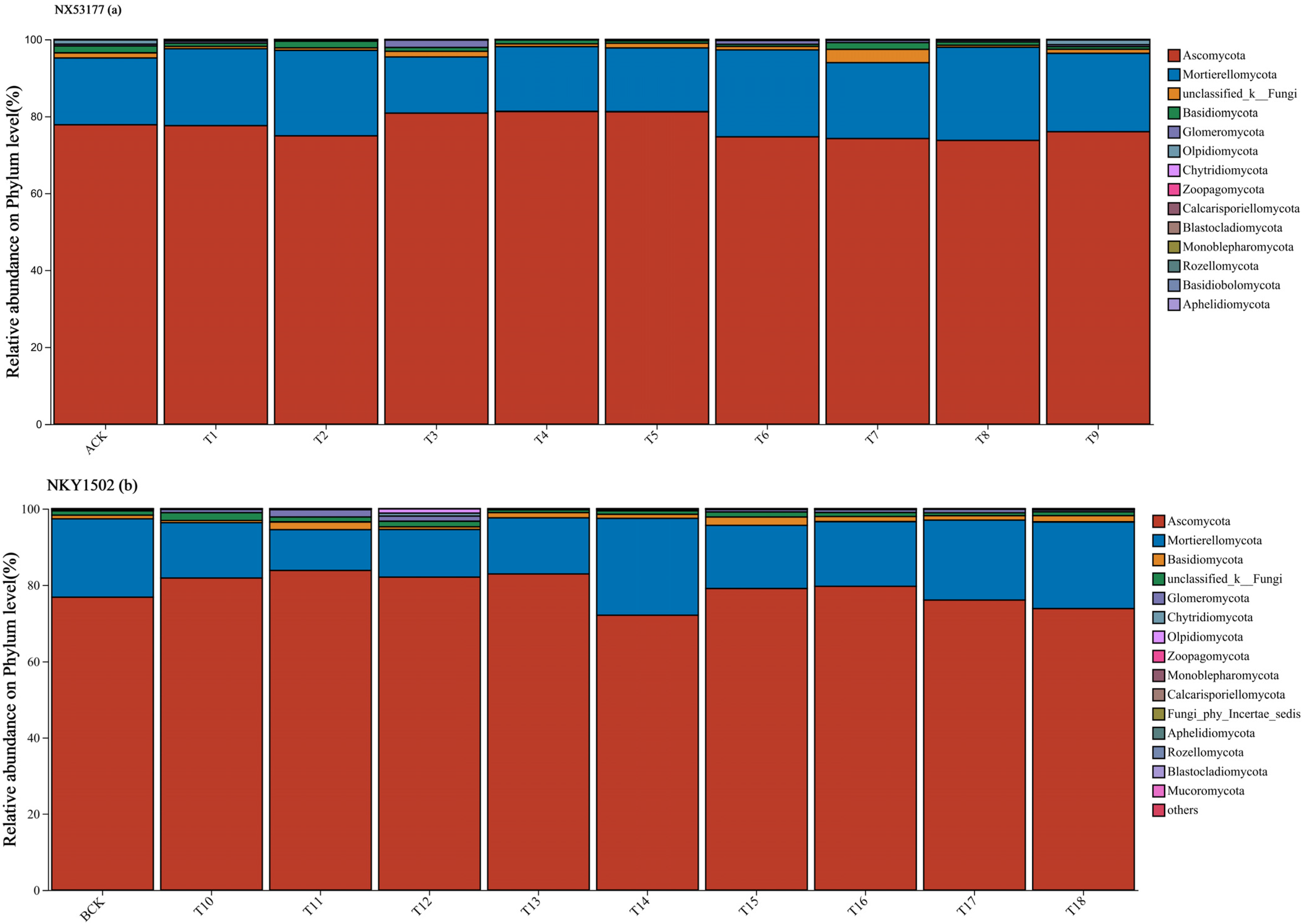

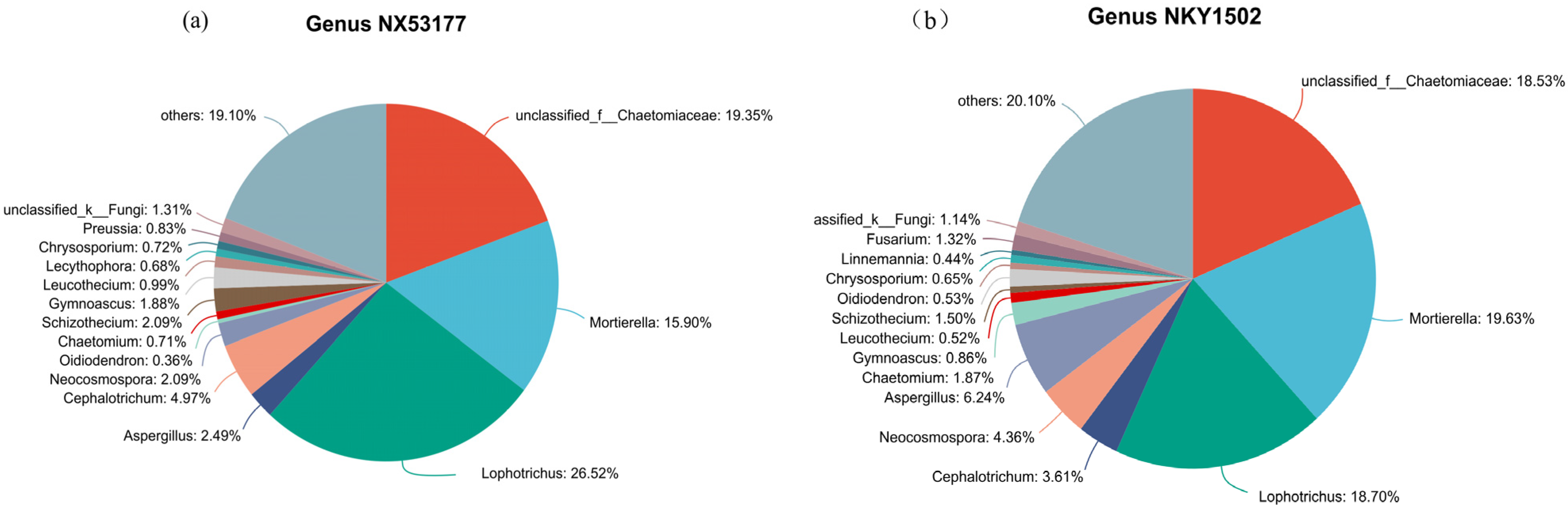

3.2. Effects of Different Microbial Fertilizers on the Abundance of Sunflower Rhizosphere Soil Fungal Communities

3.3. Effects of Different Microbial Fertilizer Treatments on Differential Species in the Rhizosphere Soil of Oil Sunflower

3.4. Effects of Different Concentrations of Microbial Fertilizers on Soil Salinity

3.5. Effects of Different Concentrations of Microbial Fertilizers on Soil Nutrients

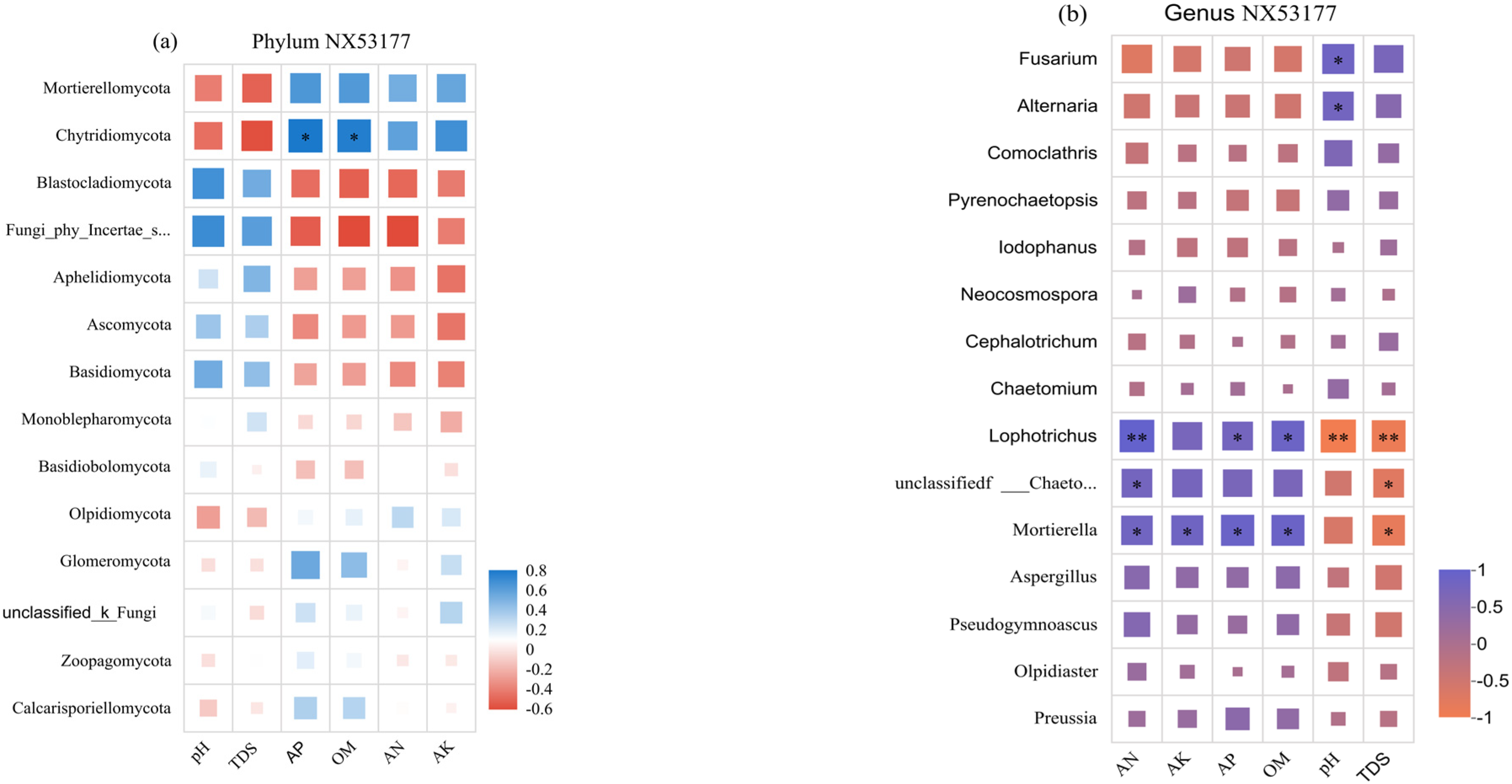

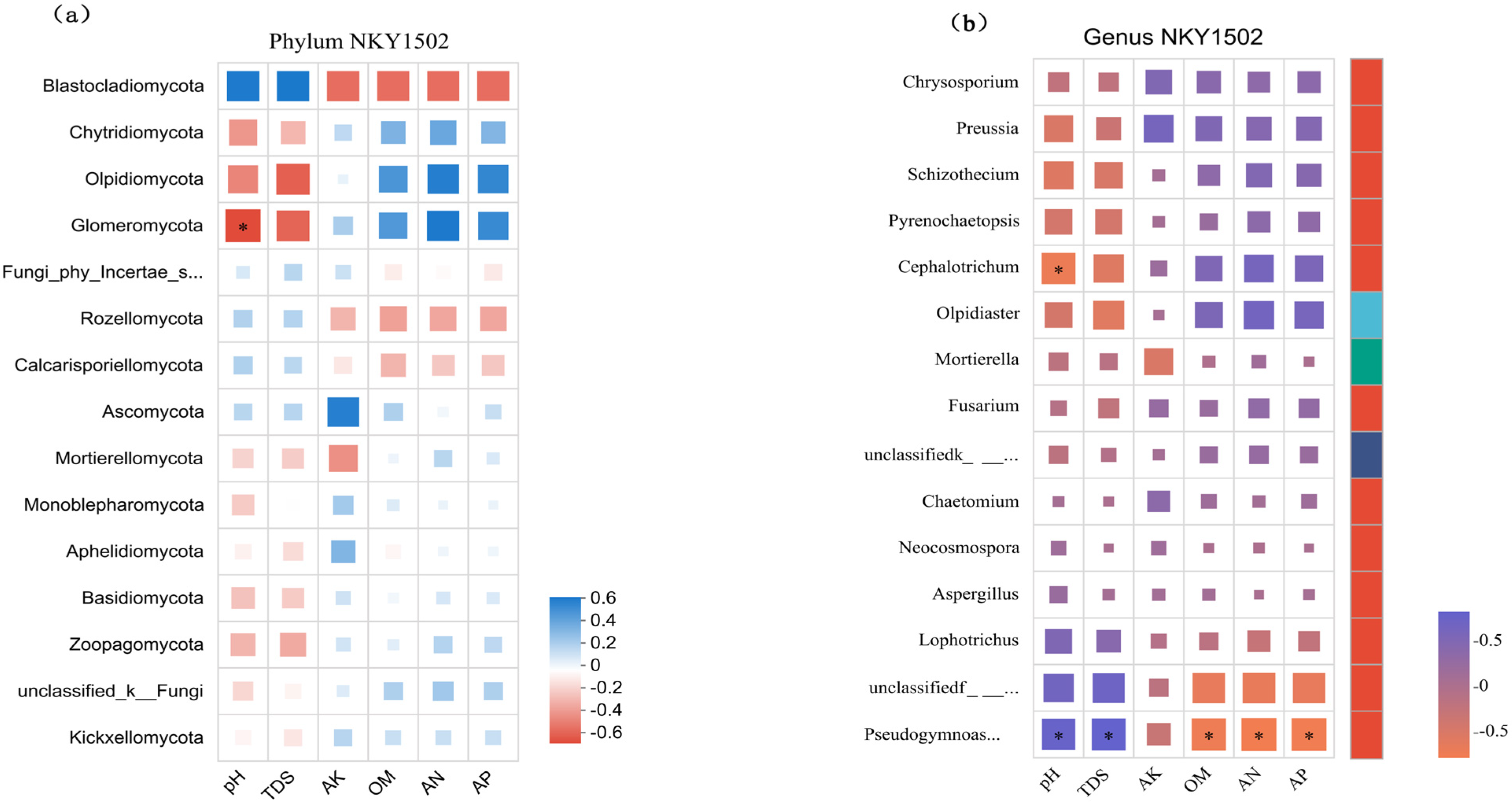

3.6. Correlation Between Soil Environmental Factors and Fungal Community Structure Under Different Microbial Fertilizer Treatments

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on the Abundance and Diversity of the Rhizosphere Soil Fungal Community

4.2. Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on Soil Salinity and Nutrients

4.3. Correlation Between the Soil Fungal Community and Soil Environmental Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhao, M.; Wang, M.; Jiang, M. Direct and indirect effects of soil salinization on soil seed banks in salinizing wetlands in the Songnen Plain, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 152035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, P.; Zhou, J.; Ge, J.; Xu, G. Characterization of the molecular, cellular, and behavioral changes caused by exposure to a saline-alkali environment in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloch, M.Y.J.; Zhang, W.; Sultana, T.; Akram, M.; Al Shoumik, B.A.; Khan, M.Z.; Farooq, M.A. Utilization of sewage sludge to manage saline–alkali soil and increase crop production: Is it safe or not? Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Zeng, W.; Jiang, Y.; Chang, A.; Wu, J.; Huang, J. Sensitivity analysis of the SWAP (soil-water-atmosphere-plant) model under different nitrogen applications and root distributions in saline soils. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Jansen, B.; Kalbitz, K.; Faz, A.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Salinity increases mobility of heavy metals in soils. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, J.; Wang, D. Phytoremediation of uranium and cadmium contaminated soils by sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) enhanced with biodegradable chelating agents. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Xu, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Divergence in fungal abundance and community structure between soils under long-term mineral and organic fertilization. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 196, 104491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xun, W.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R. Rhizosphere microbes enhance plant salt tolerance: Toward crop production in saline soil. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 6543–6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Sun, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; Lu, P.; Wu, M.; Xue, Q.; Guo, Q.; Tang, D.; Lai, H. Harnessing biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles for recruitment of beneficial soil microbes to plant roots. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cai, K.; Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Shen, H.; Zhu, S.; Xu, K.; Sun, X. Rhizobia–legume symbiosis modulates the rhizosphere microbiota and proteins which affect the growth and development of pear rootstock. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, D.; Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Reduced soil ecosystem multifunctionality is associated with altered complexity of the bacterial-fungal interkingdom network under salinization pressure. Environ. Res. 2025, 269, 120863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Xue, Z.; Yang, Z.; Chai, Z.; Shi, Z. Effects of microbial organic fertilizers on Astragalus membranaceus growth and rhizosphere microbial community. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.M.; Dean, D.R.; Seefeldt, L.C. Climbing nitrogenase: Toward a mechanism of enzymatic nitrogen fixation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, J.-X.; Shi, P.-P.; Wang, X.-X.; Du, C.-H.; Zhang, S.-S.; Zhan, H.-X. Effects of different microbial fertilizers on Codonopsis pilosula physiology and rhizosphere soil environment. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2024, 49, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lian, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Zhang, J. Combined application of organic fertilizer with microbial inoculum improved aggregate formation and salt leaching in a secondary salinized soil. Plants 2023, 12, 2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Li, P.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M.; Meng, Q.; Ye, F.; Yin, W. Study of the mechanism by which Bacillus subtilis improves the soil bacterial community environment in severely saline-alkali cotton fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 958, 178000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hao, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Tao, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, B.; Shen, Z.; et al. Biodiversity of the beneficial soil-borne fungi steered by Trichoderma-amended biofertilizers stimulates plant production. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, E. Soil biota, ecosystem services and land productivity. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 64, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Lentendu, G.; Schloter, M.; Pecyna, M.J.; Kapturska, D.; Hofrichter, M.; Krüger, D.; Buscot, F. Life in leaf litter: Novel insights into community dynamics of bacteria and fungi during litter decomposition. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 4059–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Qiu, S.; Xu, X.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Zhang, S.; He, P. Change in straw decomposition rate and soil microbial community composition after straw addition in different long-term fertilization soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 138, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000; p. 495. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chang, C.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Y.; Pan, J. Spatial-temporal characteristics of soil water and salt and its coupling relationship in the coastal area of the Yellow River Delta. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 36, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, D.; Ma, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, Q. Denitrifying sulfide removal process on high-salinity wastewaters in the presence of Halomonas sp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackebrandt, E.; Goebel, B.M. Taxonomic Note: A Place for DNA-DNA Reassociation and 16S rRNA Sequence Analysis in the Present Species Definition in Bacteriology. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1994, 44, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Lv, M.; Tian, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Jiang, Y.; Ge, S. Soil Fertility, Microbial Biomass, and Microbial Functional Diversity Responses to Four Years Fertilization in an Apple Orchard in North China. Hortic. Plant J. 2020, 6, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Din, I.U.; Arafat, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wu, T.; Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Qin, X.; et al. Antagonistic activity of Trichoderma spp. against Fusarium oxysporum in rhizosphere of Radix pseudostellariae triggers the expression of host defense genes and improves its growth under long-term monoculture system. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 579920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsonowati, W.; Marian, M.; Surono, N.K. The effectiveness of a dark septate endophytic fungus, Cladophialophora chaetospira SK51, to mitigate strawberry Fusarium wilt disease and with growth promotion activities. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhong, S.; Su, L.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Effect of biofertilizer for suppressing Fusarium wilt disease of banana as well as enhancing microbial and chemical properties of soil under greenhouse trial. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 93, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, H.; Huang, J.; Chen, Z.; Nie, Y. The rhizosphere microbial community response to a bio-organic fertilizer: Finding the mechanisms behind the suppression of watermelon Fusarium wilt disease. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2018, 40, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Feng, J.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Guo, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Integrated biocontrol of tobacco bacterial wilt by antagonistic bacteria and marigold. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Lv, N.; Deng, X.; Xiong, W.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, N.; Geisen, S.; Li, R.; et al. Additive fungal interactions drive biocontrol of Fusarium wilt disease. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1198–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Guan, Z.; Chen, S. Effects of inorganic, organic and bio-organic fertilizer on growth, rhizosphere soil microflora and soil function sustainability in chrysanthemum monoculture. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M.; Vara Prasad, M.N.; Freitas, H.; Ae, N. Biotechnological applications of serpentine soil bacteria for phytoremediation of trace metals. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2009, 29, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Z.; Liu, H. Modification of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities: A Possible Mechanism of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Enhancing Plant Growth and Fitness. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 920813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, D.; Ren, X.; Yan, J.; Ahmed, T.; Li, B. Effects of Different Microbial Fertilizers on Growth and Rhizosphere Soil Properties of Corn in Newly Reclaimed Land. Plants 2022, 11, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y. Maize (Zea mays) growth and nutrient uptake following integrated improvement of vermicompost and humic acid fertilizer on coastal saline soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 142, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Chen, A.; Chen, G.; Li, H.; Guan, S.; He, J. Microbial biofertilizer decreases nicotine content by improving soil nitrogen supply. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 180, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Yao, X.; Wu, K.; Yao, Y. Effects of different fertilization levels on rhizosphere soil fungal community structure and diversity of hulless barley and pea mixed cropping pattern. Soils 2023, 55, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.F.; Cui, X.S.; Zhu, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Characterization of root microbial communities associated with Astragalus membranaceus and their correlation with soil environmental factors. Rhizosphere 2022, 24, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.C.; Zhang, J.T.; Ye, S.P.; Wang, L.; Chen, H. Isolation, identification of a phosphate-solubilizing Penicillium strain from soil and its application effects. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2020, 6, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Chen, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, C.Z.; Ma, D.H.; Cai, Z.J.; Zhang, J.B. Effects of Mortierella on Nutrient Availability and Straw Decomposition in Soil. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2022, 59, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hydrolysable N (mg·kg−1) | Available K (mg·kg−1) | Available P (mg·kg−1) | Organic Matter (g·kg−1) | Total Soil Salinity (g/kg) | pH | EC (µS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.17 | 215.68 | 23.99 | 18.93 | 5.87 | 8.01 | 1408 |

| NX53177 | NKY1502 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Fertilizer Concentration (g/L) | Treatment | Fertilizer Concentration (g/L) | Treatment | Fertilizer Concentration (g/L) | Treatment | Fertilizer Concentration (g/L) |

| ACK | No microbial fertilizer | T5 | 100 g Polylactic acid (medium) | BCK | No microbial fertilizer | T14 | 100 g Polylactic acid (medium) |

| T1 | 100 g Qiaosengen (low) | T6 | 150 g Polylactic acid (high) | T10 | 100 g Qiaosengen (low) | T15 | 150 g Polylactic acid (high) |

| T2 | 200 g Qiaosengen (medium) | T7 | 25 g Aikesa (low) | T11 | 200 g Qiaosengen (medium) | T16 | 25 g Aikesa (low) |

| T3 | 300 g Qiaosengen (high) | T8 | 50 g Aikesa (medium) | T12 | 300 g Qiaosengen (high) | T17 | 50 g Aikesa (medium) |

| T4 | 50 g Polylactic acid (low) | T9 | 75 g Aikesa (high) | T13 | 50 g Polylactic acid (low) | T18 | 75 g Aikesa (high) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, S.; Liu, Y.; Duan, W.; Wang, K.; Wang, P.; Liu, S.; Jia, X.; Hu, Y. Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Fungal Community Diversity in Saline–Alkali Soil Cultivated with Oil Sunflowers. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2769. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122769

Guan S, Liu Y, Duan W, Wang K, Wang P, Liu S, Jia X, Hu Y. Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Fungal Community Diversity in Saline–Alkali Soil Cultivated with Oil Sunflowers. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2769. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122769

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Shangqi, Yantao Liu, Wei Duan, Kaiyong Wang, Peng Wang, Shengli Liu, Xiuping Jia, and Yutong Hu. 2025. "Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Fungal Community Diversity in Saline–Alkali Soil Cultivated with Oil Sunflowers" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2769. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122769

APA StyleGuan, S., Liu, Y., Duan, W., Wang, K., Wang, P., Liu, S., Jia, X., & Hu, Y. (2025). Effects of Microbial Fertilizer on Soil Physicochemical Properties and Fungal Community Diversity in Saline–Alkali Soil Cultivated with Oil Sunflowers. Agronomy, 15(12), 2769. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122769