Differential Expression of MYB29 Homologs and Their Subfunctionalization in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Gene Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis

2.3. Subcellular Localization Analysis

2.4. Transcription Activation Assay

2.5. Vector Construction and Stable Plant Transformation

2.6. Expression Profiling of BjuMYB29s in Brassica juncea

2.7. Insect Feeding Experiment

2.8. HPLC Analysis of Glucosinolate Content

2.9. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of Four BjuMYB29 Homologs in Brassica juncea

3.2. Subcellular Localization and Transcriptional Activity of BjuMYB29 Proteins

3.3. Spatiotemporal Expression Patterns of BjuMYB29s During Brassica juncea Development

3.4. Insect Herbivory Induces Differential Expression of BjuMYB29s

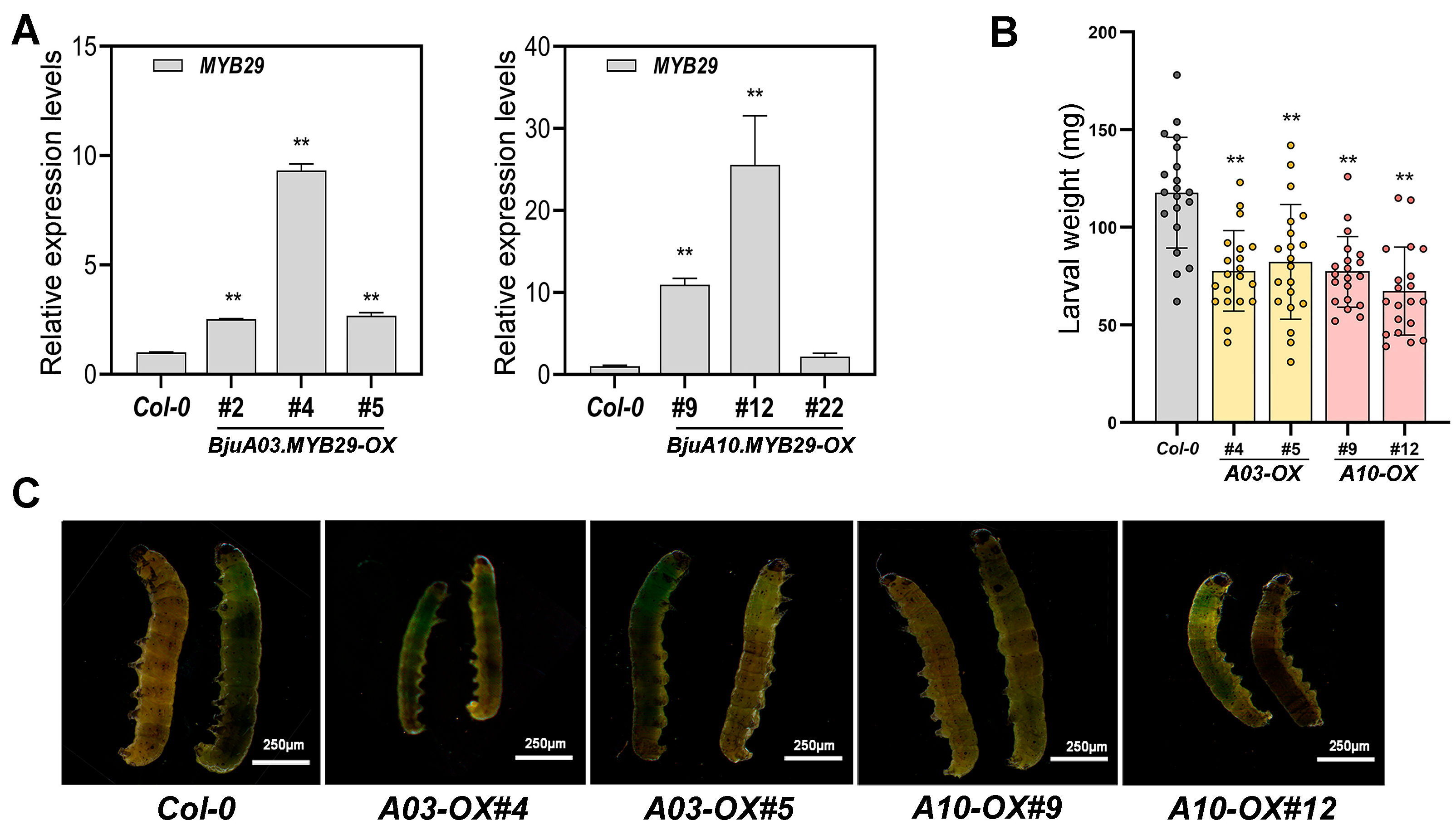

3.5. Overexpression of BjuA03.MYB29 and BjuA10.MYB29 Confers Enhanced Resistance to Beet Armyworm in Arabidopsis

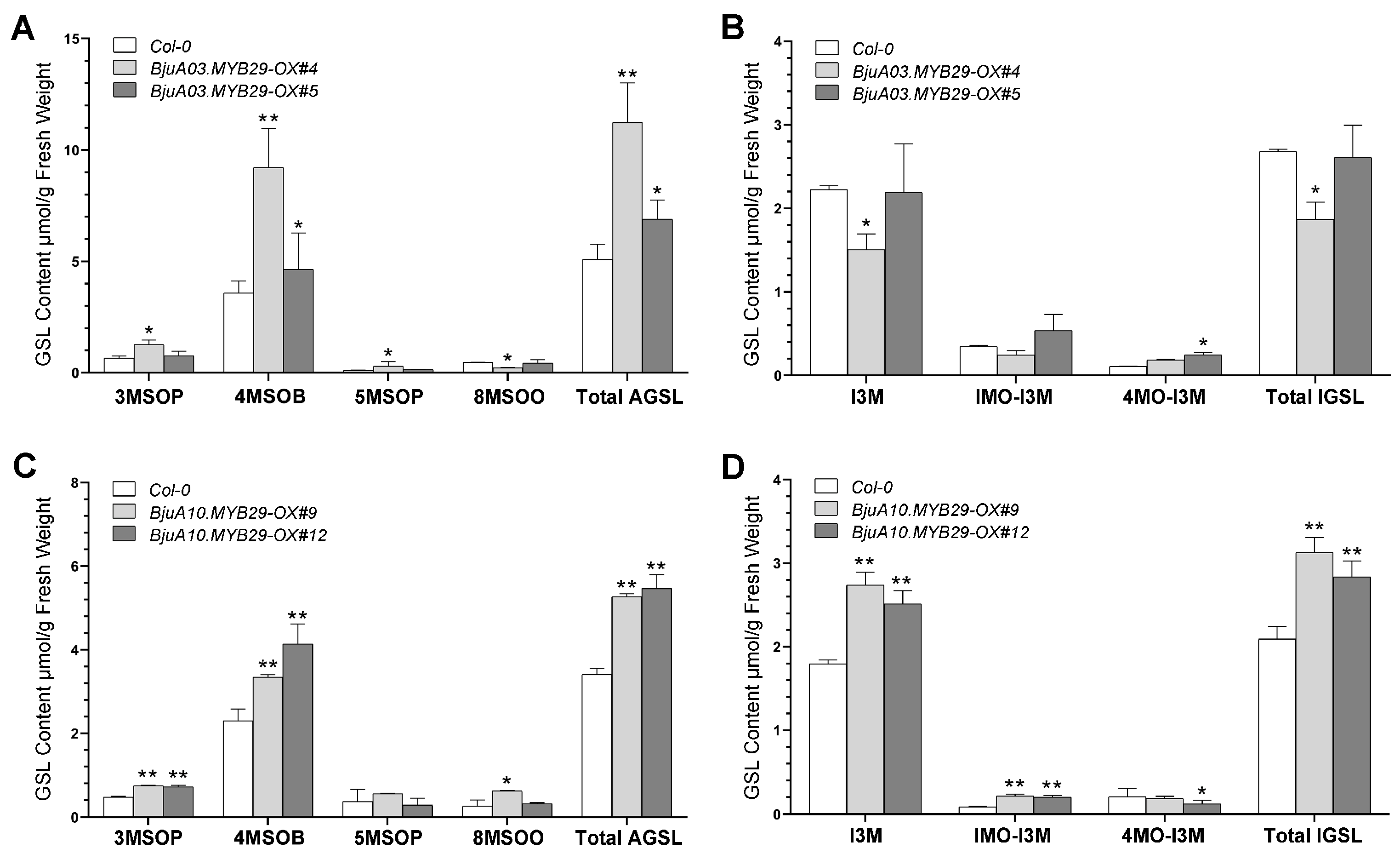

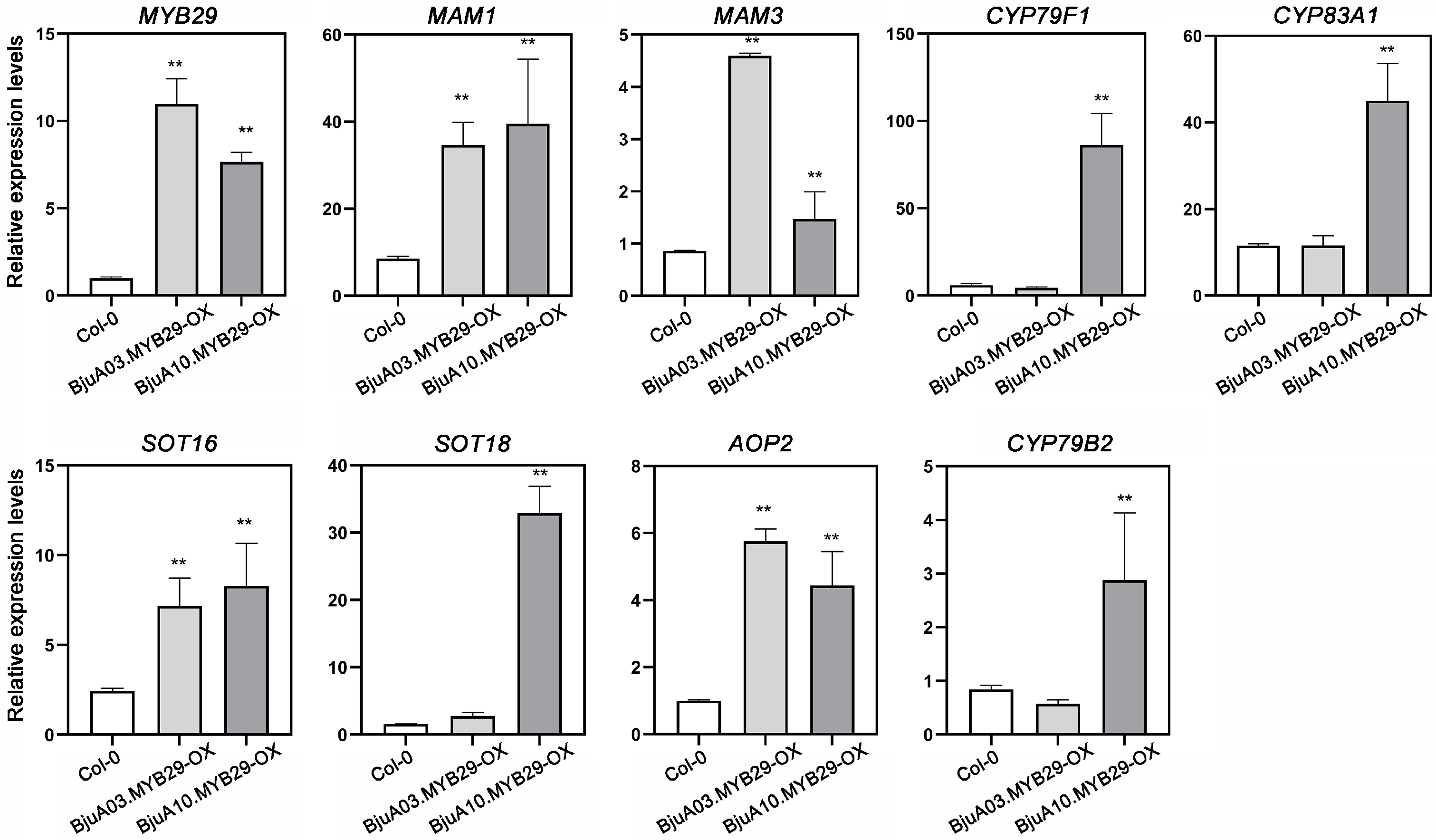

3.6. BjuA03.MYB29 and BjuA10.MYB29 Enhance Glucosinolate Production via Activating the Expression of GSL Biosynthetic Genes

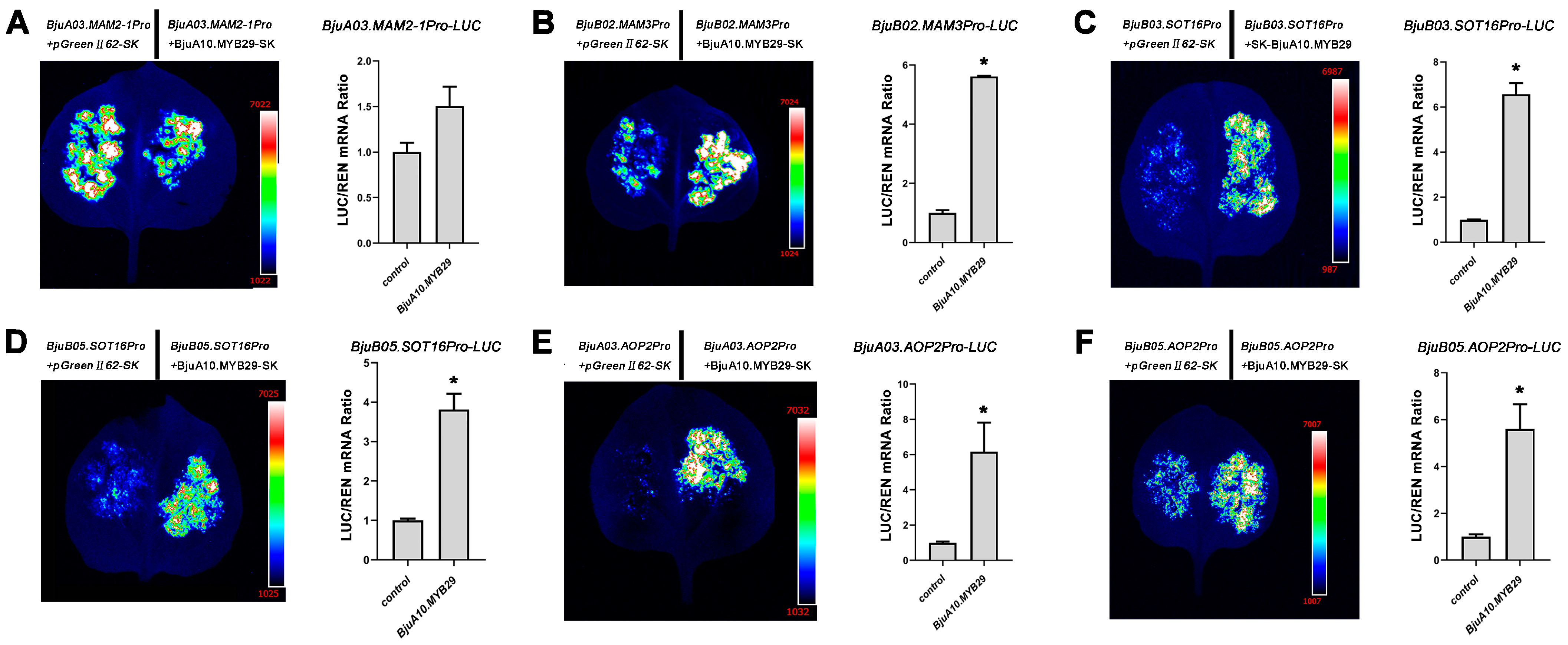

3.7. Direct Transcriptional Regulation of Glucosinolate Biosynthetic Genes by BjuA03.MYB29 and BjuA10.MYB29

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolutionary Expansion of MYB Regulators in Brassica Species

4.2. Expression Divergence of MYB29 Genes in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea

4.3. Subfunctionalization of BjuMYB29s in the Regulation of Glucosinolate Biosynthesis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fahey, J.W.; Zalcmann, A.T.; Talalay, P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 5–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitreiter, S.; Gigolashvili, T. Regulation of glucosinolate biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blažević, I.; Montaut, S.; Burčul, F.; Olsen, C.E.; Burow, M.; Rollin, P.; Agerbirk, N. Glucosinolate structural diversity, identification, chemical synthesis and metabolism in plants. Phytochemistry 2020, 169, 112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.B. Glucosinolates, structures and analysis in food. Anal. Methods 2010, 2, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Bong, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Park, Y.-K.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Park, S.U. De novo transcriptome analysis and glucosinolate profiling in watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.). BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, B.A.; Gershenzon, J. Biology and Biochemistry of Glucosinolates. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønderby, I.E.; Geu-Flores, F.; Halkier, B.A. Biosynthesis of glucosinolates--gene discovery and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, R.J.; van Dam, N.M.; van Loon, J.J.A. Role of glucosinolates in insect-plant relationships and multitrophic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2009, 54, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, P.; Cartea, M.E.; Gonzalez, C.; Vilar, M.; Ordas, A. Factors affecting the glucosinolate content of kale (Brassica oleracea acephala group). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Hara, M.; Fukino, N.; Kakizaki, T.; Morimitsu, Y. Glucosinolate metabolism, functionality and breeding for the improvement of Brassicaceae vegetables. Breed. Sci. 2014, 64, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E.; Nisani, S.; Chamovitz, D.A. Indole-3-carbinol: A plant hormone combatting cancer. F1000Research 2018, 7, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harun, S.; Abdullah-Zawawi, M.-R.; Goh, H.-H.; Mohamed-Hussein, Z.-A. A Comprehensive Gene Inventory for Glucosinolate Biosynthetic Pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 7281–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; King, G.J.; Borpatragohain, P.; Zou, J. Developing multifunctional crops by engineering Brassicaceae glucosinolate pathways. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.-S.; Kim, J.S. Understanding of MYB Transcription Factors Involved in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Brassicaceae. Molecules 2017, 22, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigolashvili, T.; Yatusevich, R.; Berger, B.; Müller, C.; Flügge, U.-I. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor HAG1/MYB28 is a regulator of methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007, 51, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigolashvili, T.; Engqvist, M.; Yatusevich, R.; Müller, C.; Flügge, U.-I. HAG2/MYB76 and HAG3/MYB29 exert a specific Blackwell Publishing Ltd and coordinated control on the regulation of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2008, 177, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønderby, I.E.; Hansen, B.G.; Bjarnholt, N.; Ticconi, C.; Halkier, B.A.; Kliebenstein, D.J. A systems biology approach identifies a R2R3 MYB gene subfamily with distinct and overlapping functions in regulation of aliphatic glucosinolates. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønderby, I.E.; Burow, M.; Rowe, H.C.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Halkier, B.A. A complex interplay of three R2R3 MYB transcription factors determines the profile of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celenza, J.L.; Quiel, J.A.; Smolen, G.A.; Merrikh, H.; Silvestro, A.R.; Normanly, J.; Bender, J. The Arabidopsis ATR1 Myb transcription factor controls indolic glucosinolate homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frerigmann, H.; Gigolashvili, T. MYB34, MYB51, and MYB122 distinctly regulate indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2014, 7, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, Z.; Gerenda’s, J.; Zimmermann, N. Glucosinolates in Chinese Brassica campestris Vegetables: Chinese Cabbage, Purple Cai-tai, Choysum, Pakchoi, and Turnip. Hortscience 2008, 43, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangkadilok, N.; Nicolas, M.E.; Bennett, R.N.; Premier, R.R.; Eagling, D.R.; Taylor, P.W.J. Developmental changes of sinigrin and glucoraphanin in three Brassica species (Brassica nigra, Brassica juncea and Brassica oleracea var. italica). Sci. Hortic. 2002, 96, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; de Vos, R.C.H.; Qian, H.; Bucher, J.; Bonnema, G. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Profiles in Diverse Brassica oleracea Crops Provide Insights into the Genetic Regulation of Glucosinolate Profiles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 16032–16044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzl, G.; Rezaeva, B.R.; Kumlehn, J.; Dörmann, P. Ablation of glucosinolate accumulation in the oil crop Camelina sativa by targeted mutagenesis of genes encoding the transporters GTR1 and GTR2 and regulators of biosynthesis MYB28 and MYB29. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhi, Y.S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Arumugam, N.; Verma, J.K.; Gupta, V.; Pental, D.; Pradhan, A.K. Genetic analysis of total glucosinolate in crosses involving a high glucosinolate Indian variety and a low glucosinolate line of Brassica juncea. Plant Breed. 2002, 121, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, E.; Zang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, Z. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals Candidate Key Genes Involved in Sinigrin Biosynthesis in Brassica nigra. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, B.; Cheng, F.; Sun, R.; Wang, X. Glucosinolate biosynthetic genes in Brassica rapa. Gene 2011, 487, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Cao, W.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Ji, J. Glucosinolate Biosynthetic Genes of Cabbage: Genome-Wide Identification, Evolution, and Expression Analysis. Genes 2023, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Xu, L.; Hao, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, Y. Transcriptome Dynamics of Brassica juncea Leaves in Response to Omnivorous Beet Armyworm (Spodoptera exigua, Hübner). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.-E.; Robin, A.H.K.; Yang, K.; Park, J.-I.; Kang, J.-G.; Yang, T.-J.; Nou, I.-S. Identification and expression analysis of glucosinolate biosynthetic genes and estimation of glucosinolate contents in edible organs of Brassica oleracea subspecies. Molecules 2015, 20, 13089–13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.-X.; Kim, H.U.; Kim, J.A.; Lim, M.-H.; Jin, M.; Lee, S.C.; Kwon, S.-J.; Lee, S.-I.; Hong, J.K.; Park, T.-H.; et al. Genome-wide identification of glucosinolate synthesis genes in Brassica rapa. FEBS J. 2010, 276, 3559–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization By One Table (tvBOT): A web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, C.; Yuan, W.; Miao, H.; Deng, M.; Wang, M.; Lin, J.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Q. Functional Characterization of BoaMYB51s as Central Regulators of Indole Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra Bailey. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, H.; Miao, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Xia, C.; Zeng, W.; Sun, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; et al. WRKY33-mediated indolic glucosinolate metabolic pathway confers resistance against Alternaria brassicicola in Arabidopsis and Brassica crops. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, R.; Majee, M.; Gershenzon, J.; Bisht, N.C. Four genes encoding MYB28, a major transcriptional regulator of the aliphatic glucosinolate pathway, are differentially expressed in the allopolyploid Brassica juncea. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 4907–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysak, M.A.; Koch, M.A.; Pecinka, A.; Schubert, I. Chromosome triplication found across the tribe Brassiceae. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Genome triplication drove the diversification of Brassica plants. Hortic. Res. 2014, 1, 14024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, W.C.; Swain, M.L.; Ma, D.; An, H.; Bird, K.A.; Curdie, D.D.; Wang, S.; Ham, H.D.; Luzuriaga-Neira, A.; Kirkwood, J.S.; et al. The final piece of the Triangle of U: Evolution of the tetraploid Brassica carinata genome. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4143–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Li, X.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Park, S.U. MYB transcription factors regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis in different organs of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Molecules 2013, 18, 8682–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.J.; Fitzgerald, T.L.; Stiller, J.; Berkman, P.J.; Gardiner, D.M.; Manners, J.M.; Henry, R.J.; Kazan, K. The defence-associated transcriptome of hexaploid wheat displays homoeolog expression and induction bias. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Ma, Z.; Mao, H. Duplicate Genes Contribute to Variability in Abiotic Stress Resistance in Allopolyploid Wheat. Plants 2023, 12, 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliebenstein, D.J. A role for gene duplication and natural variation of gene expression in the evolution of metabolism. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhunova, A.R.; Matniyazov, R.T.; Liang, H.; Akhunov, E.D. Homoeolog-specific transcriptional bias in allopolyploid wheat. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, B.; Flagel, L.; Stupar, R.M.; Udall, J.A.; Verma, N.; Springer, N.M.; Wendel, J.F. Reciprocal silencing, transcriptional bias and functional divergence of homeologs in polyploid cotton (gossypium). Genetics 2009, 182, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Magusin, A.; Trick, M.; Fraser, F.; Bancroft, I. Use of mRNA-seq to discriminate contributions to the transcriptome from the constituent genomes of the polyploid crop species Brassica napus. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M.-J.; Szadkowski, E.; Wendel, J.F. Homoeolog expression bias and expression level dominance in allopolyploid cotton. Heredity 2013, 110, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Feng, M.; Yang, G.; Sun, L.; Qin, Z.; Cao, J.; Wen, J.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Changes in Alternative Splicing in Response to Domestication and Polyploidization in Wheat. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.G.; Huang, S.Z.; Pin, A.-L.; Adams, K.L. Extensive divergence in alternative splicing patterns after gene and genome duplication during the evolutionary history of Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix, K.; Gérard, P.R.; Schwarzacher, T.; Heslop-Harrison, J.S.P. Polyploidy and interspecific hybridization: Partners for adaptation, speciation and evolution in plants. Ann. Bot. 2017, 120, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop-Harrison, J.S.P.; Schwarzacher, T.; Liu, Q. Polyploidy: Its consequences and enabling role in plant diversification and evolution. Ann. Bot. 2023, 131, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc, G.; Wolfe, K.H. Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGiorgio, M.; Assis, R. Learning Retention Mechanisms and Evolutionary Parameters of Duplicate Genes from Their Expression Data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 1209–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, R.; Hasumi, A.; Nishizawa, O.I.; Sasaki, K.; Kuwahara, A.; Sawada, Y.; Totoki, Y.; Toyoda, A.; Sakaki, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Novel bioresources for studies of Brassica oleracea: Identification of a kale MYB transcription factor responsible for glucosinolate production. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013, 11, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, D.L.; Graham, N.S.; Klinder, A.; van Ommen Kloeke, A.E.E.; Marcotrigiano, A.R.; Wagstaff, C.; Verkerk, R.; Sonnante, G.; Aarts, M.G.M. Overexpression of the MYB29 transcription factor affects aliphatic glucosinolate synthesis in Brassica oleracea. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 101, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittipol, V.; He, Z.; Wang, L.; Doheny-Adams, T.; Langer, S.; Bancroft, I. Genetic architecture of glucosinolate variation in Brassica napus. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 240, 152988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandayu, E.; Borpatragohain, P.; Mauleon, R.; Kretzschmar, T. Genome-Wide Association Reveals Trait Loci for Seed Glucosinolate Accumulation in Indian Mustard (Brassica juncea L.). Plants 2022, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Zeng, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B.; Wang, Q. Improvement of glucosinolates by metabolic engineering in Brassica crops. aBIOTECH 2021, 2, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, L. Differential Expression of MYB29 Homologs and Their Subfunctionalization in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122770

Zhang L, Wang J, Wang S, Yu Y, Zhu Z, Xu L. Differential Expression of MYB29 Homologs and Their Subfunctionalization in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122770

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lili, Jingjing Wang, Shanyi Wang, Youjian Yu, Zhujun Zhu, and Liai Xu. 2025. "Differential Expression of MYB29 Homologs and Their Subfunctionalization in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122770

APA StyleZhang, L., Wang, J., Wang, S., Yu, Y., Zhu, Z., & Xu, L. (2025). Differential Expression of MYB29 Homologs and Their Subfunctionalization in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea. Agronomy, 15(12), 2770. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122770