Optimizing Sowing Time Using Cumulative Temperature-Tailored Yield of Vegetable Soybean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Weather Information

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.4. Growth Parameters, Yield, and Yield Components

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

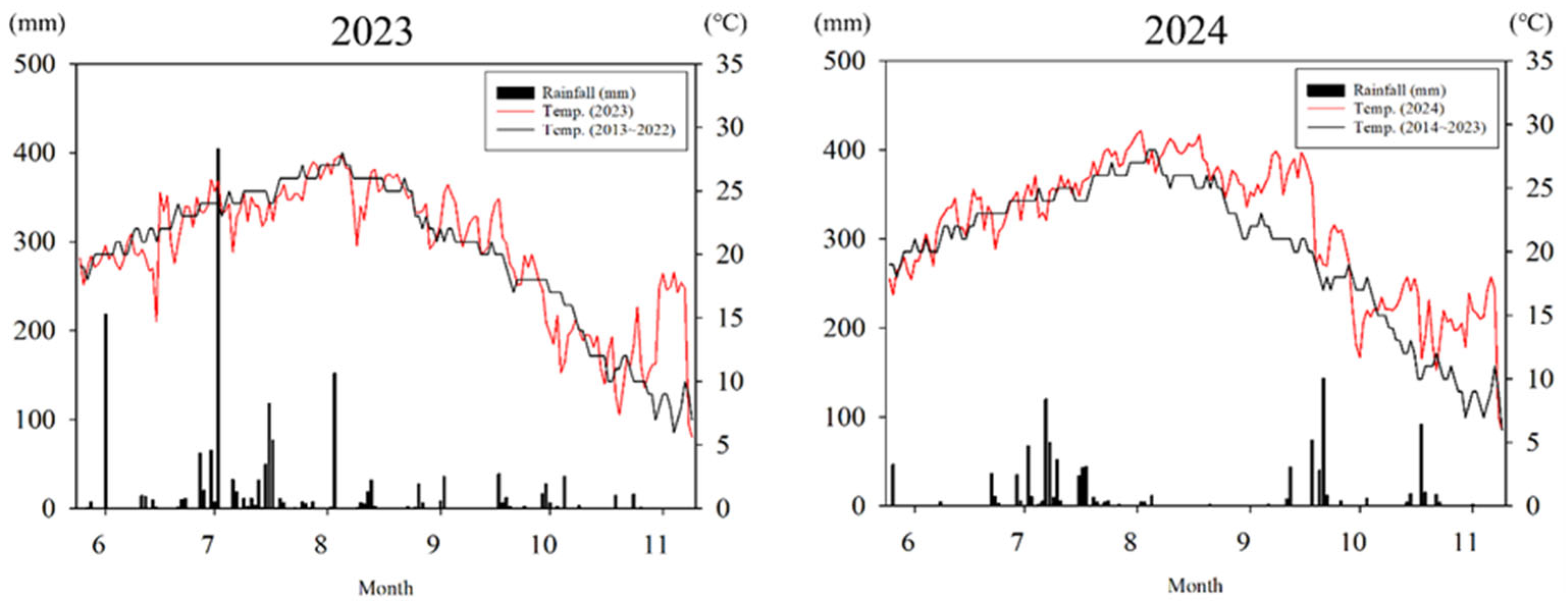

3.1. Temperature and Precipitation During the Experiment

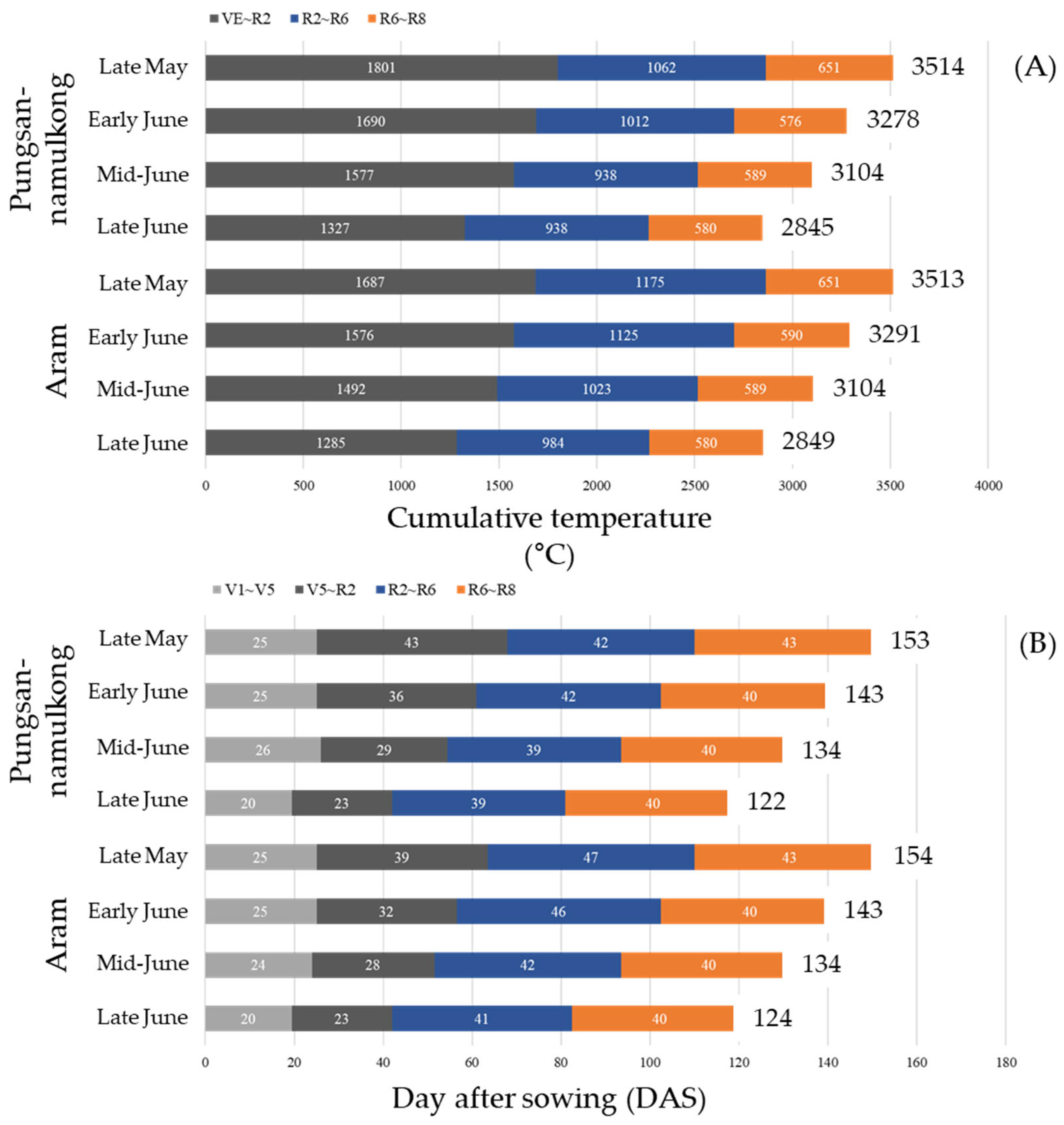

3.2. Cumulative Temperature and Growing Days by Sowing Date

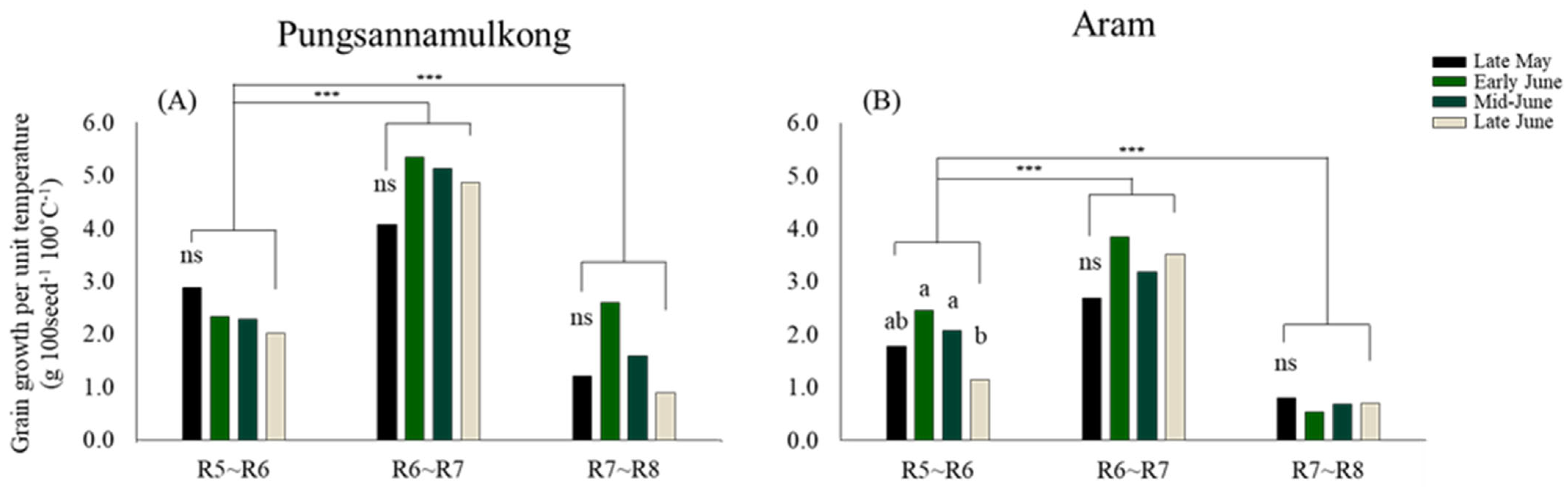

3.3. Growth Parameters, Yield Components, and Yield

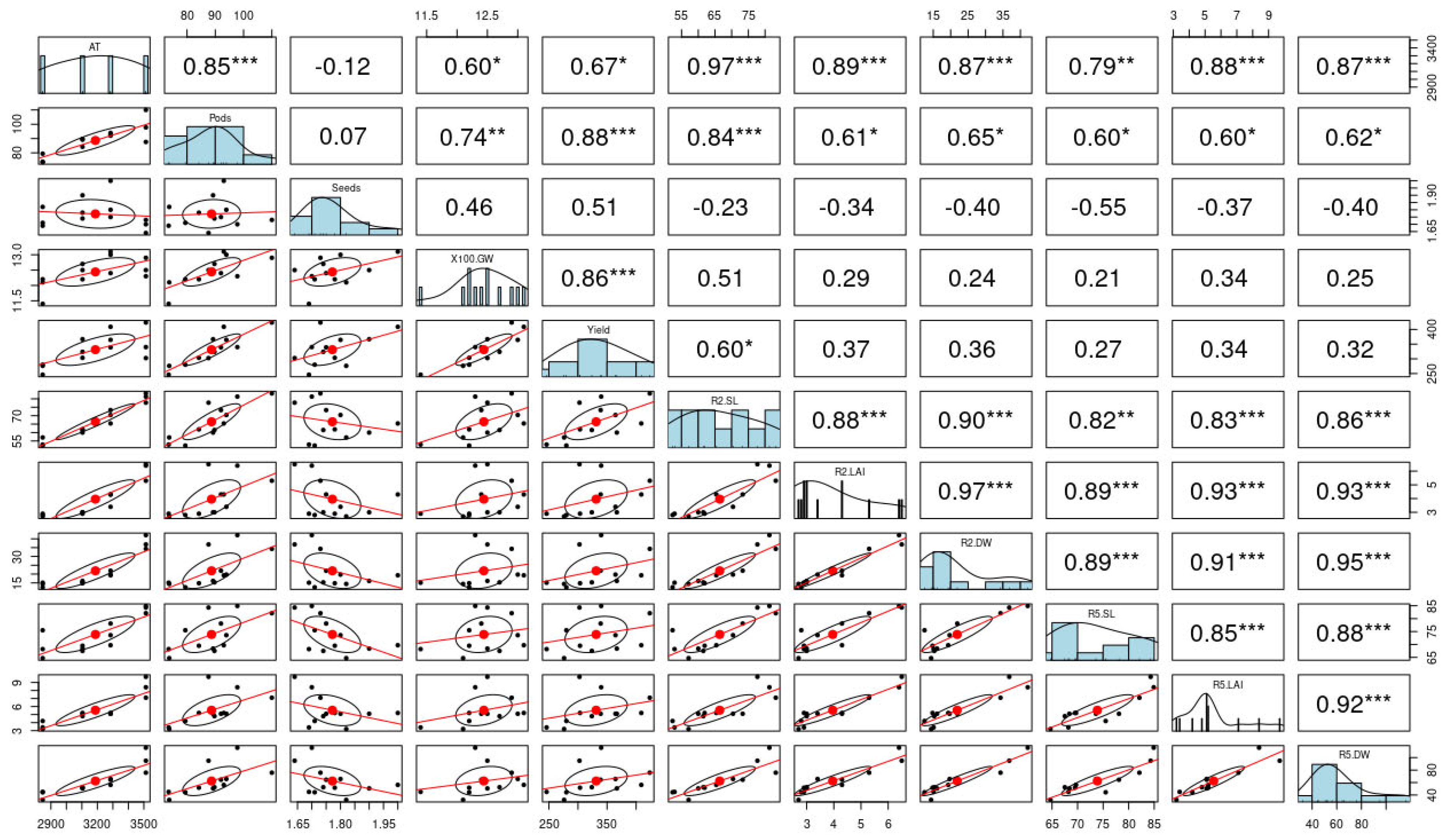

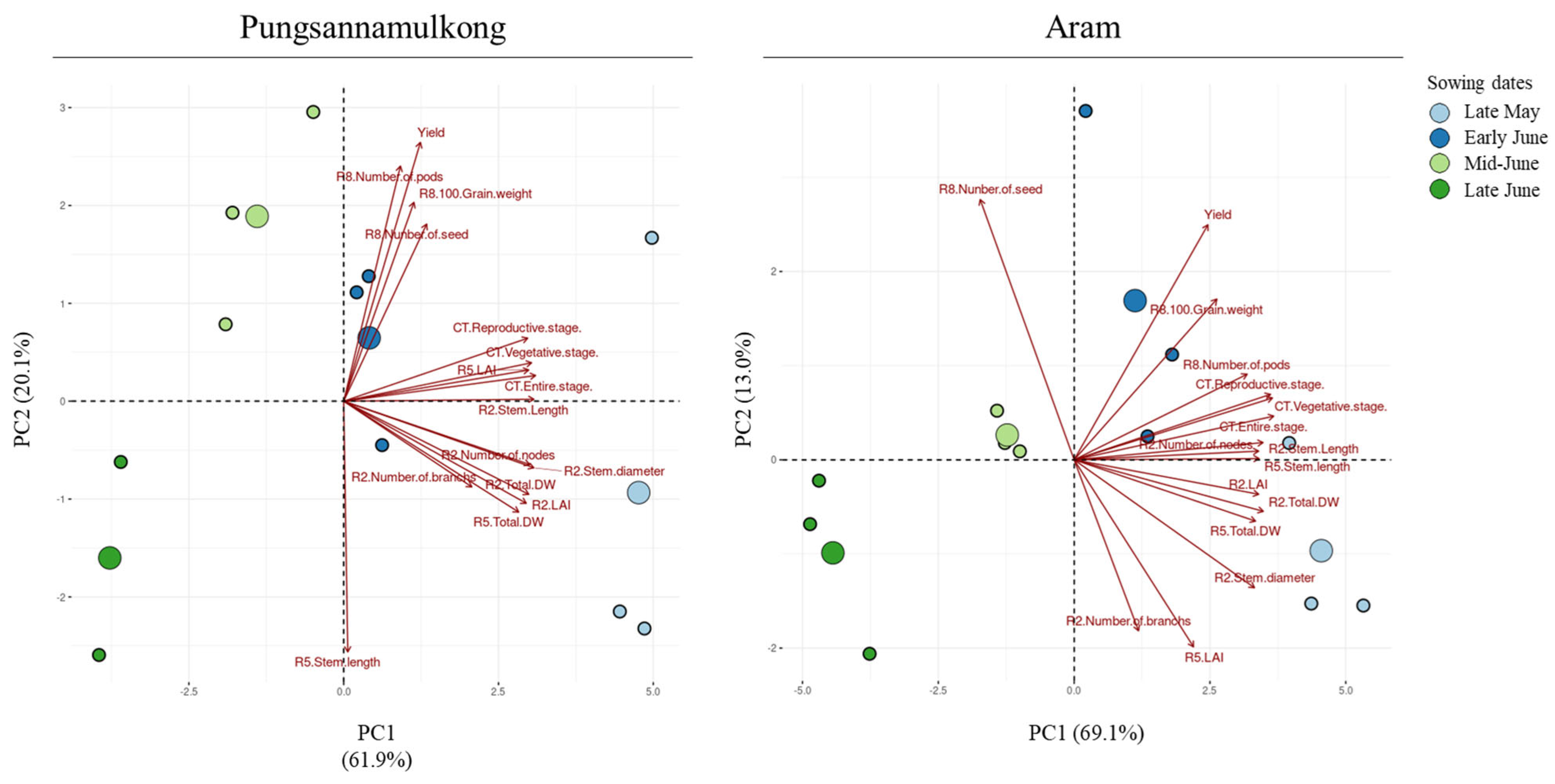

3.4. Correlation and Principal Components Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Cumulative Temperature (CT), Growing Days, Soybean Growth, and Yield

4.2. Correlation and PCA

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Cumulative temperature |

References

- Li, B.; Gao, K.; Ren, H.; Tang, W. Molecular Mechanisms Governing Plant Responses to High Temperatures. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 757–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenveettil, N.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Reddy, K.N.; Gao, W.; Reddy, K.R. Temperature and Elevated CO2 Alter Soybean Seed Yield and Quality, Exhibiting Transgenerational Effects on Seedling Emergence and Vigor. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1427086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lobell, D.B.; Huang, Y.; Huang, M.; Yao, Y.; Bassu, S.; Ciais, P.; et al. Temperature Increase Reduces Global Yields of Major Crops in Four Independent Estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9326–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsajri, F.A.; Wijewardana, C.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Irby, J.T.; Krutz, J.; Golden, B.; Reddy, V.R.; Reddy, K.R. Morpho-Physiological, Yield, and Transgenerational Seed Germination Responses of Soybean to Temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 839270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Alghabari, F.; Rauf, M.; Zhao, T.; Javed, M.M.; Alshamrani, R.; Ghazy, A.-H.; Al-Doss, A.A.; Khalid, T.; Yang, S.H. Optimization of Soybean Physiochemical, Agronomic, and Genetic Responses under Varying Regimes of Day and Night Temperatures. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1332414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mall, R.; Lal, M.; Bhatia, V.; Rathore, L.; Singh, R. Mitigating Climate Change Impact on Soybean Productivity in India: A Simulation Study. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzinis, S.; Specht, J.E.; Conley, S.P. Defining Optimal Soybean Sowing Dates Across the US. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowntree, S.C.; Suhre, J.J.; Weidenbenner, N.H.; Wilson, E.W.; Davis, V.M.; Naeve, S.L.; Casteel, S.N.; Diers, B.W.; Esker, P.D.; Specht, J.E.; et al. Genetic Gain × Management Interactions in Soybean: I. Planting Date. Crop Sci. 2013, 53, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nico, M.; Miralles, D.J.; Kantolic, A.G. Natural Post-Flowering Photoperiod and Photoperiod Sensitivity: Roles in Yield Determining Processes in Soybean. Field Crops Res. 2019, 231, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiyono, T.D.; Weiss, A.; Specht, J.; Bastidas, A.M.; Cassman, K.G.; Dobermann, A. Understanding and Modeling the Effect of Temperature and Daylength on Soybean Phenology Under High-Yield Conditions. Field Crops Res. 2007, 100, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divito, G.A.; Echeverría, H.E.; Andrade, F.H.; Sadras, V.O. Soybean Shows an Attenuated Nitrogen Dilution Curve Irrespective of Maturity Group and Sowing Date. Field Crops Res. 2016, 186, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, N.; Esendal, E. Response to Inoculation and Sowing Date of Soybean Under Bafra Plain Conditions in the Northern Region of Turkey. Turk. J. Agric. For. 1998, 22, 525–531. [Google Scholar]

- KOSIS 2023 Crop Production Statistics (2214-5141). 2024. Available online: https://kosis.kr (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- RDA. Standard Fertilization Recommendation; Version 5; RDA: Jeonju, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J.; Sung, J.K.; Lee, S.B.; Lim, J.E.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, D.B.; Hong, S.Y. Plant analysis methods for evaluating mineral nutrient. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2017, 50, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.-Y.; Park, K.-Y.; Kim, H.-T.; Ko, J.-M.; Baek, I.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y.; Choung, M.-G. Variations in Growth Characteristics and Seed Qualities of Korean Soybean Landraces. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2008, 53, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.E.; Jung, G.H.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, M.T.; Shin, S.H.; Jeon, W.T. Effects of Growth Period and Cumulative Temperature on Flowering, Ripening and Yield of Soybean by Sowing Times. Korean J. Crop Sci. 2019, 64, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantolic, A.G.; Peralta, G.E.; Slafer, G.A. Seed Number Responses to Extended Photoperiod and Shading during Reproductive Stages in Indeterminate Soybean. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 51, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh-e, I.; Uwagoh, R.; Jyo, S.; Kurahashi, T.; Saitoh, K.; Kuroda, T. Effect of Rising Temperature on Flowering, Pod Set, Dry-Matter Production and Seed Yield in Soybean. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 2007, 76, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhuang, Q.; Luo, Y. Adaptation of Paddy Rice in China to Climate Change: The Effects of Shifting Sowing Date on Yield and Irrigation Water Requirement. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 228, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Wiatrak, P. Effect of Planting Date on Soybean Growth, Yield, and Grain Quality. Agron. J. 2012, 104, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Księżak, J.; Bojarszczuk, J. The Seed Yield of Soybean Cultivars and Their Quantity Depending on Sowing Term. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin-Andrzejewska, M.; Helios, W.; Jama-Rodzeńska, A.; Kozak, M.; Kotecki, A.; Kuchar, L. Effect of Sowing Date on Soybean Development in South-Western Poland. Agriculture 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Shin, P.; Youn, J.; Sung, J.; Jeon, S. The Effect of Sowing Date on Soybean Growth and Yield under Changing Climate in the Southern Coastal Region of Korea. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Zheng, A.; Harrison, M.T.; Li, W.; Zou, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, F.; Yin, X. Optimal Sowing Time to Adapt Soybean Production to Global Warming with Different Cultivars in the Huanghuaihai Farming Region of China. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzinis, S.; Gaspar, A.P.; Naeve, S.L.; Conley, S.P. Planting Date, Maturity, and Temperature Effects on Soybean Seed Yield and Composition. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 2040–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsajri, F.A.; Wijewardana, C.; Irby, J.T.; Bellaloui, N.; Krutz, L.J.; Golden, B.; Gao, W.; Reddy, K.R. Developing Functional Relationships Between Temperature and Soybean Yield and Seed Quality. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.P.; Conley, S.P.; Volenec, J.J.; Santini, J.B. Analysis of High-Yielding, Early-Planted Soybean in Indiana. Agron. J. 2009, 101, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.; Mullen, R. Soybean Seed Quality Reductions by High Day and Night Temperature. Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 1615–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, A.; Shiraiwa, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Horie, T. The Effect of Temperature during the Reproductive Period on Development of Reproductive Organs and the Occurrence of Delayed Stem Senescence in Soybean. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 2005, 74, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variety | Sowing Date | R2 (Full Bloom) | R5 (Beginning Seed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Length (cm) | LAI | Dry Weight (g plant−1) | Stem Length (cm) | LAI | Dry Weight (g plant−1) | ||

| Pungsan namulkong | Late May | 74.2 ± 3.1 a | 7.48 ± 3.05 a | 47.3 ± 19.3 a | 70.4 ± 4.8 ab | 9.57 ± 5.24 a | 112.0 ± 45.1 a |

| Early June | 64.7 ± 5.2 b | 3.96 ± 1.06 b | 20.1 ± 6.3 b | 63.0 ± 8.7 bc | 6.08 ± 1.34 b | 66.5 ± 14.7 b | |

| Mid-June | 52.4 ± 8.2 c | 2.93 ± 0.34 b | 16.0 ± 6.2 b | 54.5 ± 4.5 c | 5.60 ± 1.81 b | 50.7 ± 14.0 b | |

| Late June | 50.6 ± 6.8 c | 2.99 ± 0.85 b | 15.1 ± 3.3 b | 75.0 ± 17.9 a | 2.52 ± 0.67 c | 46.0 ± 10.9 b | |

| F-value | 32.83 *** | 24.8 *** | 96.83 *** | 11.98 ** | 30.68 *** | 15.59 ** | |

| Aram | Late May | 87.2 ± 6.6 a | 4.67 ± 0.73 a | 28.0 ± 5.1 a | 97.1 ± 6.5 a | 7.21 ± 4.42 ns | 79.0 ± 31.7 a |

| Early June | 74.7 ± 4.7 b | 4.02 ± 1.53 ab | 20.5 ± 7.1 b | 84.6 ± 8.2 a | 4.18 ± 0.47 | 57.8 ± 13.0 ab | |

| Mid-June | 69.8 ± 3.1 b | 3.01 ± 0.93 bc | 14.9 ± 4.4 bc | 82.4 ± 1.6 a | 4.40 ± 0.77 | 52.5 ± 13.1 ab | |

| Late June | 57.5 ± 11.5 c | 2.62 ± 0.56 c | 12.9 ± 4.4 c | 63.9 ± 12.9 b | 4.64 ± 2.53 | 35.1 ± 7.0 b | |

| F-value | 23.39 *** | 14.76 ** | 19.94 *** | 14.85 ** | 4.251 * | 7.884 ** | |

| ANOVA | Var (V) | 59.93 (***) | 12.227 (**) | 28.264 (***) | 60.771 (***) | 2.596 (ns) | 7.359 (*) |

| Sowing (S) | 56.572 (***) | 48.047 (***) | 108.725 (***) | 11.162 (***) | 15.445 (***) | 25.537 (***) | |

| Year (Y) | 1.869 (ns) | 0.488 (ns) | 0.743 (ns) | 1.099 (ns) | 23.334 (***) | 12.295 (**) | |

| V × S | 2.19 (ns) | 10.161 (***) | 19.515 (***) | 19.529 (***) | 3.823 (*) | 2.426 (ns) | |

| V × Y | 0.625 (ns) | 25.398 (***) | 27.69 (***) | 5.095 (*) | 0.304 (ns) | 0 (ns) | |

| S × Y | 7.684 (***) | 21.781 (***) | 37.689 (***) | 2.448 (ns) | 10.274 (***) | 7.741 (***) | |

| V × S × Y | 2.027 (ns) | 4.115 (*) | 15.47 (***) | 7.659 (***) | 2.098 (ns) | 2.56 (ns) | |

| Variety | Sowing Time | Pods (No. plant−1) | Seeds (No. pod−1) | 100-Seed Weight (g) | Yield (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pungsan namulkong | Late May | 87.4 ± 19.2 ab | 1.77 ± 0.25 ns | 13.4 ± 1.0 ns | 3525 ± 888 ns |

| Early June | 82.7 ± 26.3 ab | 1.80 ± 0.27 | 13.7 ± 1.6 | 3409 ± 145 | |

| Mid-June | 96.1 ± 32.0 a | 1.77 ± 0.32 | 13.2 ± 0.9 | 3725 ± 610 | |

| Late June | 75.8 ± 12.7 b | 1.70 ± 0.21 | 12.7 ± 1.1 | 2807 ± 338 | |

| F-value | 4.882 * | 0.615 | 0.844 | 1.448 | |

| Aram | Late May | 110 ± 14 a | 1.61 ± 0.25 ns | 11.8 ± 1.1 a | 3581 ± 430 ab |

| Early June | 103 ± 10 a | 1.90 ± 0.26 | 12.0 ± 0.5 a | 4007 ± 591 a | |

| Mid-June | 79. 3 ± 9.2 b | 1.84 ± 0.26 | 11.7 ± 0.2 a | 2902 ± 43 bc | |

| Late June | 75.2 ± 7.5 b | 1.79 ± 0.11 | 11.0 ± 0.2 b | 2540 ± 120 c | |

| F-value | 13.26 ** | 2.143 | 20.8 *** | 9.514 ** | |

| ANOVA | Var (V) | 2.925 (ns) | 0.215 (ns) | 65.867 (***) | 0.358 (ns) |

| Sowing (S) | 7.057 (***) | 2.323 (ns) | 3.793 (*) | 6.276 (**) | |

| Year (Y) | 31.139 (***) | 53.414 (***) | 1.424 (ns) | 0.749 (ns) | |

| V × S | 6.351 (**) | 1.838 (ns) | 0.085 (ns) | 2.677 (ns) | |

| V × Y | 9.587 (**) | 2.201 (ns) | 27.521 (***) | 11.487 (**) | |

| S × Y | 1.671 (ns) | 3.005 (*) | 4.055 (*) | 3.126 (*) | |

| V × S × Y | 1.465 (ns) | 0.721 (ns) | 1.6 (ns) | 1.426 (ns) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, B.; Kim, M.; Jeon, S.; Shin, P.; Jang, H.; Sung, J. Optimizing Sowing Time Using Cumulative Temperature-Tailored Yield of Vegetable Soybean. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122767

Lee J, Kim M, Lee B, Kim M, Jeon S, Shin P, Jang H, Sung J. Optimizing Sowing Time Using Cumulative Temperature-Tailored Yield of Vegetable Soybean. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122767

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jeongmin, Minji Kim, Boyun Lee, Minchang Kim, SeungHo Jeon, Pyeong Shin, Hyeonsoo Jang, and Jwakyung Sung. 2025. "Optimizing Sowing Time Using Cumulative Temperature-Tailored Yield of Vegetable Soybean" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122767

APA StyleLee, J., Kim, M., Lee, B., Kim, M., Jeon, S., Shin, P., Jang, H., & Sung, J. (2025). Optimizing Sowing Time Using Cumulative Temperature-Tailored Yield of Vegetable Soybean. Agronomy, 15(12), 2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122767