Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Sequence Analysis of the WOX Transcription Factor Family Members in Passion Fruit

2.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment and the Phylogenetic Tree

2.3. Gene Structure, Conserved Motif, and Cis-Regulatory Elements Analysis

2.4. Chromosome Localization and Synteny Analysis

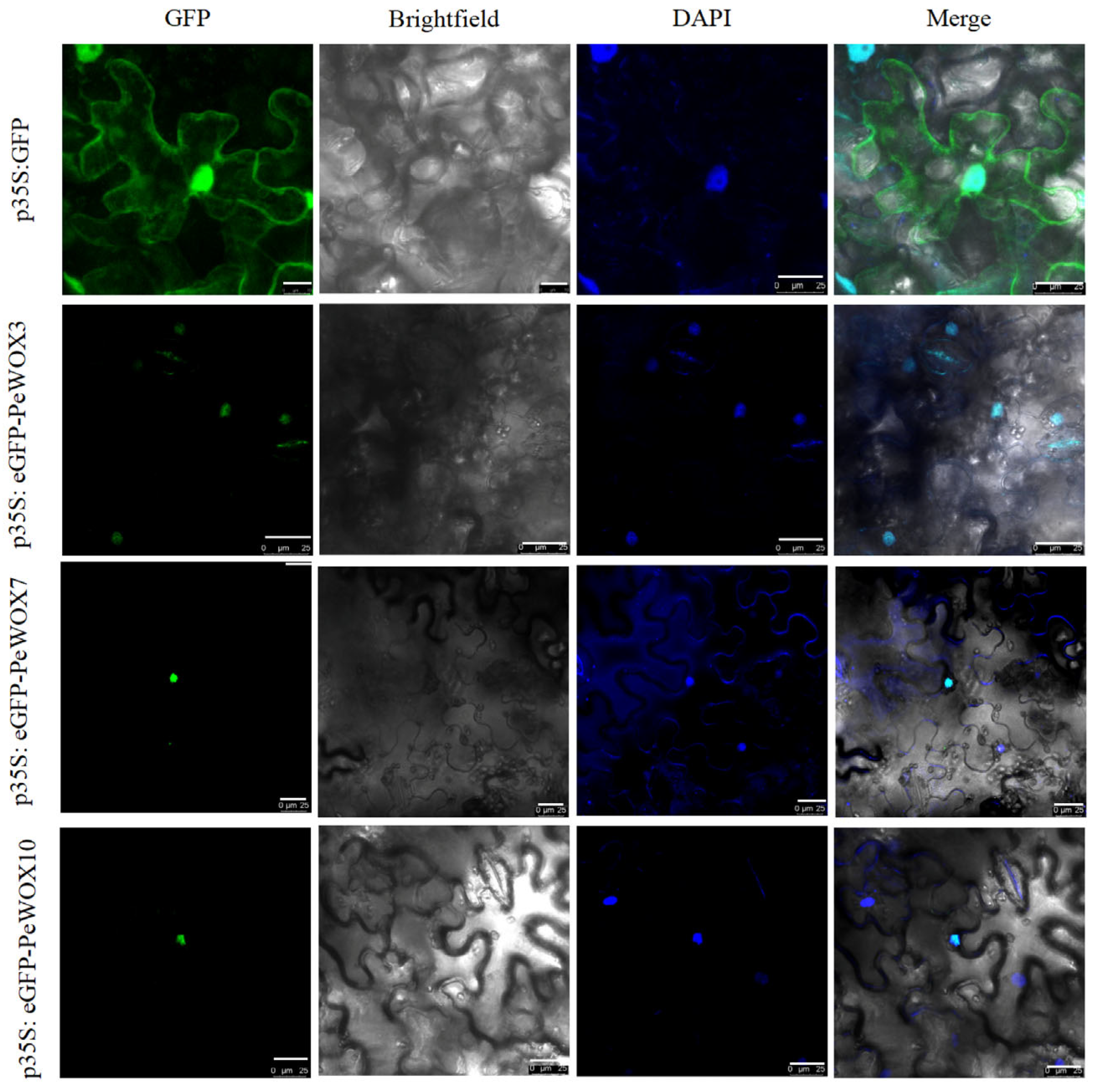

2.5. Subcellular Localization of PeWOXs

2.6. Expression Patterns Analysis Based on RNA-SEQ Data

2.7. Plant Materials and Treatment Methods

2.8. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of PeWOX Genes

3.2. Identification and Analysis of Homeodomain

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

3.4. Analysis of the Exon/Intron Structure and Conserved Motifs of the Passion Fruit WOX Gene Family

3.5. Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements in PeWOX Promoters

3.6. Chromosomal Distribution and Synteny Analysis

3.7. Subcellular Localization of PeWOXs Protein

3.8. Expression Patterns of PeWOXs in Different Tissues of Passion Fruit

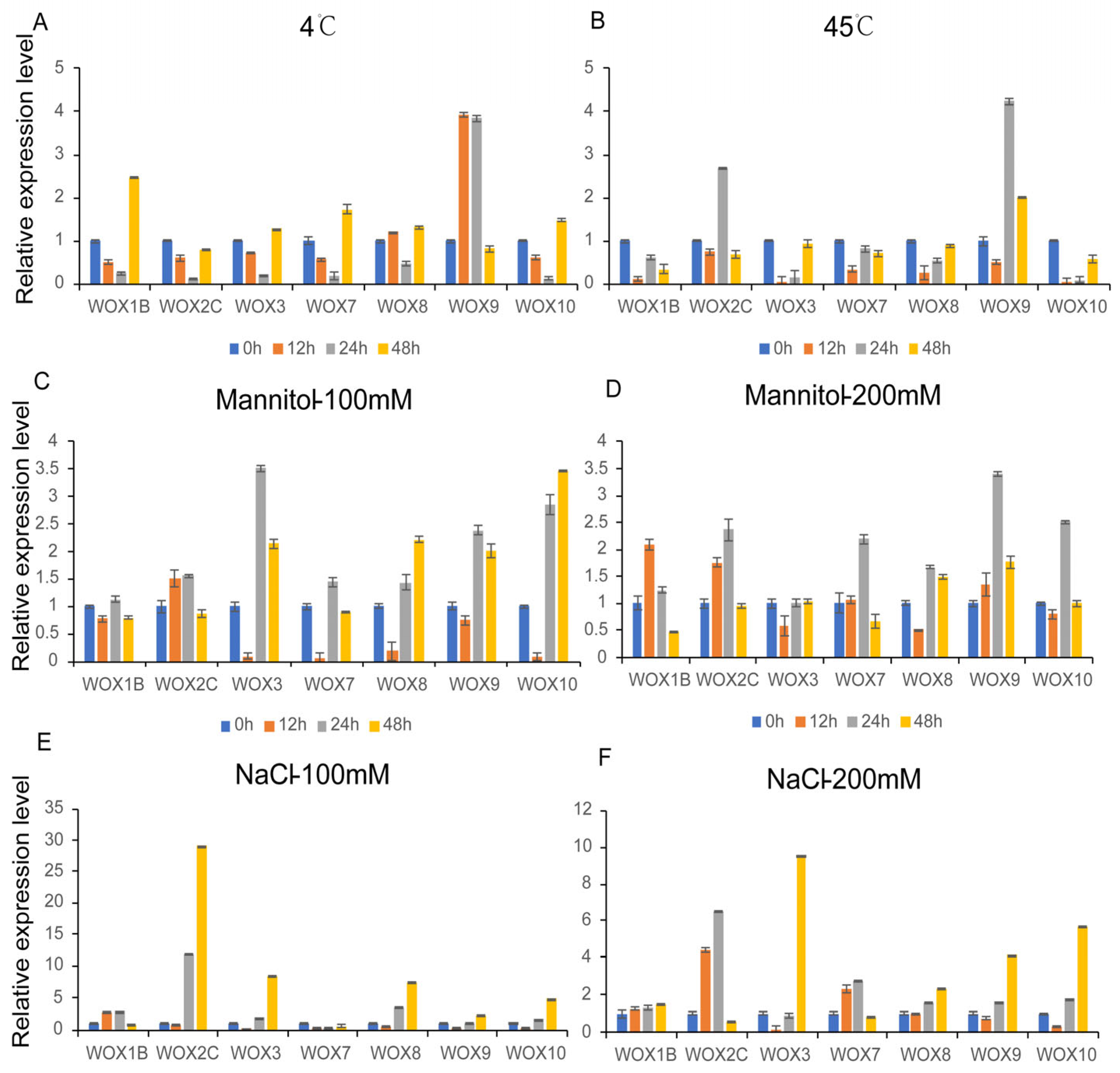

3.9. Expression Patterns of PeWOXs in Different Abiotic Stress Treatments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gehring, W.J.; Müller, M.; Affolter, M.; Percival-Smith, A.; Billeter, M.; Qian, Y.Q.; Otting, G.; Wüthrich, K. The structure of the homeodomain and its functional implications. Trends Genet. 1990, 6, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, W.J.; Qian, Y.Q.; Billeter, M.; Furukubo-Tokunaga, K.; Schier, A.F.; Resendez-Perez, D.; Affolter, M.; Otting, G.; Wüthrich, K. Homeodomain-DNA recognition. Cell 1994, 78, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehring; Walter, J.J.G. Exploring the homeobox. Gene 1993, 135, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Graaff, E.; Laux, T.; Rensing, S.A.J.G.B. The WUS homeobox-containing (WOX) protein family. Genome Biol. 2009, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Brocchieri, L.; Bürglin, T.R. A comprehensive classification and evolutionary analysis of plant homeobox genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 2775–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuil-Broyer, S.; Trehin, C.; Morel, P.; Boltz, V.; Sun, B.; Chambrier, P.; Ito, T.; Negrutiu, I. Analysis of the Arabidopsis superman allelic series and the interactions with other genes demonstrate developmental robustness and joint specification of male–female boundary, flower meristem termination and carpel compartmentalization. Ann. Bot. 2016, 117, mcw023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, T.; Mayer, K.F.; Berger, J.; Jurgens, G. The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 1996, 122, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.; Hao, Y.; Cui, H. The WUSCHEL Related Homeobox Protein WOX7 Regulates the Sugar Response of Lateral Root Development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suer, S.; Agusti, J.; Sanchez, P.; Schwarz, M.; Greb, T. WOX4Imparts Auxin Responsiveness to Cambium Cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3247–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haecker, A. Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 2004, 131, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, R.; Ji, J.; Kelsey, E.; Ohtsu, K.; Schnable, P.S.; Scanlon, M.J. Tissue specificity and evolution of meristematic WOX3 function. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera-Branchat, M.; Ripoll, J.J.; Yanofsky, M.F.; Pelaz, S. The WOX13 homeobox gene promotes replum formation in the Arabidopsis thaliana fruit. Plant J. 2013, 73, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, R.; Qin, G.; Chen, Z.; Gu, H.; Qu, L.J. Over-expression of WOX1 Leads to Defects in Meristem Development and Polyamine Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzali, S.; Novi, G.; Loreti, E.; Paolicchi, F.; Poggi, A.; Alpi, A.; Perata, P. A turanose-insensitive mutant suggests a role for WOX5 in auxin homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005, 44, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sheng, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Huang, H.; Xu, L. WOX11 and 12 Are Involved in the First-Step Cell Fate Transition during de Novo Root Organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Dabi, T.; Weigel, D. Requirement of Homeobox Gene STIMPY/WOX9 for Arabidopsis Meristem Growth and Maintenance-ScienceDirect. Curr. Biol. Cb 2005, 15, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.O. The PRETTY FEW SEEDS2 gene encodes an Arabidopsis homeodomain protein that regulates ovule development. Development 2005, 132, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Lucini, L.; Torchio, F.; Dordoni, R.; De Faveri, D.M.; Lambri, M. Metabolite profiling and volatiles of pineapple wine and vinegar obtained from pineapple waste. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talcott, S.T.; Percival, S.S.; Pittet-Moore, J.; Celoria, C. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant stability of fortified yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leterme, P.; Buldgen, A.; Estrada, F.; Londoño, A.M. Mineral content of tropical fruits and unconventional foods of the Andes and the rain forest of Colombia. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, P.R.; Valvassori, S.S.; Bordignon, C.L., Jr.; Kappel, V.D.; Martins, M.R.; Gavioli, E.C.; Quevedo, J.; Reginatto, F.H. The aqueous extracts of Passiflora alata and Passiflora edulis reduce anxiety-related behaviors without affecting memory process in rats. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleta, M.; Batista, M.T.; Campos, M.G.; Carvalho, R.; Cotrim, M.D.; Lima, T.C.M.d.; Cunha, A.P.d. Neuropharmacological evaluation of the putative anxiolytic effects of Passiflora edulis Sims, its sub-fractions and flavonoid constituents. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, L.M.; Zucolotto, S.M.; Reginatto, F.H.; Schenkel, E.P.; De Lima, T.C. Neuropharmacological activity of the pericarp of Passiflora edulis flavicarpa degener: Putative involvement of C-glycosyl flavonoids. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 234, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Doerks, T.; Bork, P. SMART 7: Recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D302–D305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artimo, P.; Jonnalagedda, M.; Arnold, K.; Baratin, D.; Csardi, G.; de Castro, E.; Duvaud, S.; Flegel, V.; Fortier, A.; Gasteiger, E.; et al. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W597–W603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C.; Shen, H.-B. Cell-PLoc: A package of Web servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Xu, J. Origins and evolution of WUSCHEL-related homeobox protein family in plant kingdom. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 534140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I.M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouet, P.; Robert, X.; Courcelle, E. ESPript/ENDscript: Extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3320–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, T.; Berg, H.; Li, C.; Xia, Y. The Arabidopsis U-box/ARM repeat E3 ligase AtPUB4 influences growth and degeneration of tapetal cells, and its mutation leads to conditional male sterility. Plant J. 2013, 74, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Hou, Z.; Liao, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Su, W.; Cai, Z.; Fang, Y.; Aslam, M.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of LBD Transcription Factor Genes in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, D.; Deng, K.; Chai, G.; Huang, Y.; Ma, S.; Qin, Y.; Wang, L. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the SBP Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Su, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, H.; Qin, Y. ERECTA signaling controls Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture through chromatin-mediated activation of PRE1 expression. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 1579–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zong, J.; Liu, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, D. Genome-wide analysis of WOX gene family in rice, sorghum, maize, Arabidopsis and poplar. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2010, 52, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, M.; Cheng, H.; Yan, M.; Priyadarshani, S.; Zhang, M.; He, Q.; Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; et al. Identification and expression analysis of the DREB transcription factor family in pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.). PeerJ 2020, 8, e9006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cui, X.; Meng, Z.; Huang, X.; Xie, Q.; Wu, H.; Jin, H.; Zhang, D.; Liang, W. Transcriptional regulation of Arabidopsis MIR168a and argonaute1 homeostasis in abscisic acid and abiotic stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Jin, X.F.; Xiong, A.S.; Peng, R.H.; Hong, Y.H.; Yao, Q.H.; Chen, J.M. Expression of a rice DREB1 gene, OsDREB1D, enhances cold and high-salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. BMB Rep. 2009, 42, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.E.; Kadonaga, J.T. The RNA polymerase II core promoter: A key component in the regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 2583–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Sun, L.; Bao, N.; Zhang, T.; Cui, C.X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Jasmonate-mediated wound signaling promotes plant regeneration. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Fu, Q.; Jing, W.; Zhang, H.; Jian, H.; Qiu, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Genome-wide identification of WOX family members in rose and functional analysis of RcWUS1 in embryogenic transformation. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, E.; Trehin, C.; Vandenbussche, M. The role of WOX genes in flower development. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Huang, L.; Lu, H.; Xia, C.; Ramirez, C.; Gao, M.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, F. The ubiquitin ligase SINA3 and the transcription factor WOX14 regulate tomato growth and development. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.F.; Li, Y.C.; Shen, Y.H.; Yang, C.H. PaWOX3 and PaWOX3B Regulate Flower Number and the Lip Symmetry of Phalaenopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2024, 65, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-C.; Lin, K.-H.; Ho, S.-L.; Chiang, C.-M.; Yang, C.-M. Enhancing the abiotic stress tolerance of plants: From chemical treatment to biotechnological approaches. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 164, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | Chromosome | PL (aa) | pI | MW (kDa) | pI | Exons | SCLpred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PeWOX1A | P_edulia010000107.g | Chr01 | 438 | 6.35 | 49.90 | 6.35 | 7 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX1B | P_edulia010004045.g | Chr01 | 215 | 5.45 | 24.62 | 5.45 | 4 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX2A | P_edulia020006114.g | Chr02 | 256 | 5.98 | 28.45 | 5.98 | 2 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX2B | P_edulia020006459.g | Chr02 | 401 | 8.73 | 44.06 | 8.73 | 5 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX2C | P_edulia020006727.g | Chr02 | 842 | 5.93 | 92.06 | 5.93 | 18 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX3 | P_edulia030008708.g | Chr03 | 185 | 5.39 | 21.22 | 5.39 | 2 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX7 | P_edulia070018572.g | Chr07 | 839 | 6.18 | 92.64 | 6.18 | 18 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX8 | P_edulia080019407.g | Chr08 | 870 | 6.08 | 94.78 | 6.08 | 20 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX9 | P_edulia090020960.g | Chr09 | 851 | 5.97 | 93.33 | 5.97 | 17 | Nucleus |

| PeWOX10 | P_eduliaContig30022774.g | Contig 3 | 867 | 5.7 | 94.97 | 5.7 | 17 | Nucleus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, J.; Zhang, D.; Xu, L.; Wu, T.; Olunuga, O.A.; Arabzai, M.G.; Wang, X.; Zheng, P.; Cheng, Y.; Tang, B.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis). Agronomy 2025, 15, 2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122766

Gao J, Zhang D, Xu L, Wu T, Olunuga OA, Arabzai MG, Wang X, Zheng P, Cheng Y, Tang B, et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis). Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122766

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Jingai, Dan Zhang, Lixin Xu, Ting Wu, Omotola Adebayo Olunuga, Mohammad Gul Arabzai, Xiaomei Wang, Ping Zheng, Yan Cheng, Boping Tang, and et al. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis)" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122766

APA StyleGao, J., Zhang, D., Xu, L., Wu, T., Olunuga, O. A., Arabzai, M. G., Wang, X., Zheng, P., Cheng, Y., Tang, B., Cai, H., Qin, Y., & Wang, L. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the WUSCHEL-Related Homeobox (WOX) Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora edulis). Agronomy, 15(12), 2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122766