Resistance of Creeping Bentgrass to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: A Model System for Grass Stress Biology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research on Disease Resistance of Creeping Bentgrass

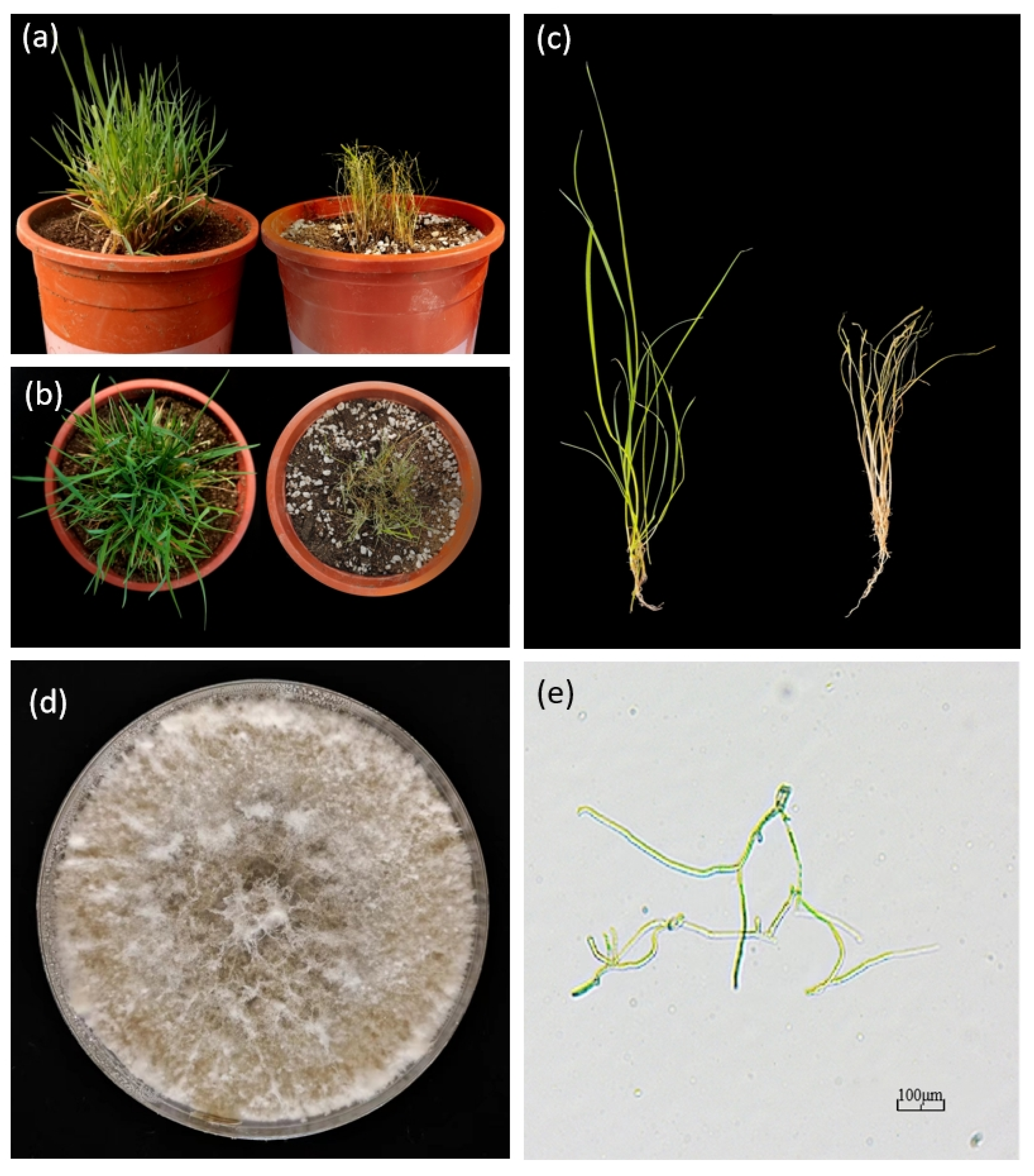

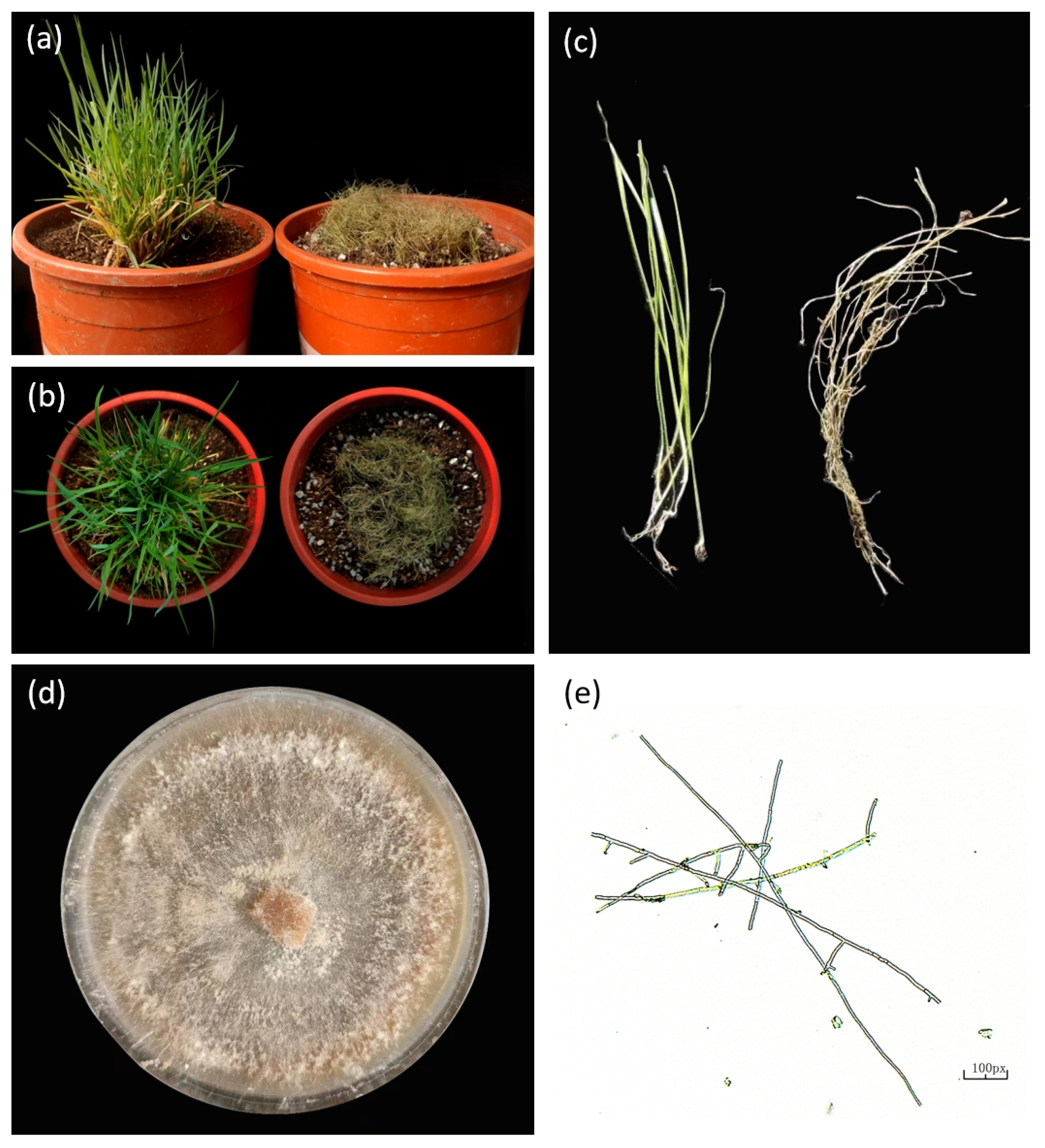

2.1. Dollar Spot Disease

2.2. Brown Patch

2.3. Bacterial Etiolation

2.4. Microdochium Patch

3. Research on Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Creeping Bentgrass

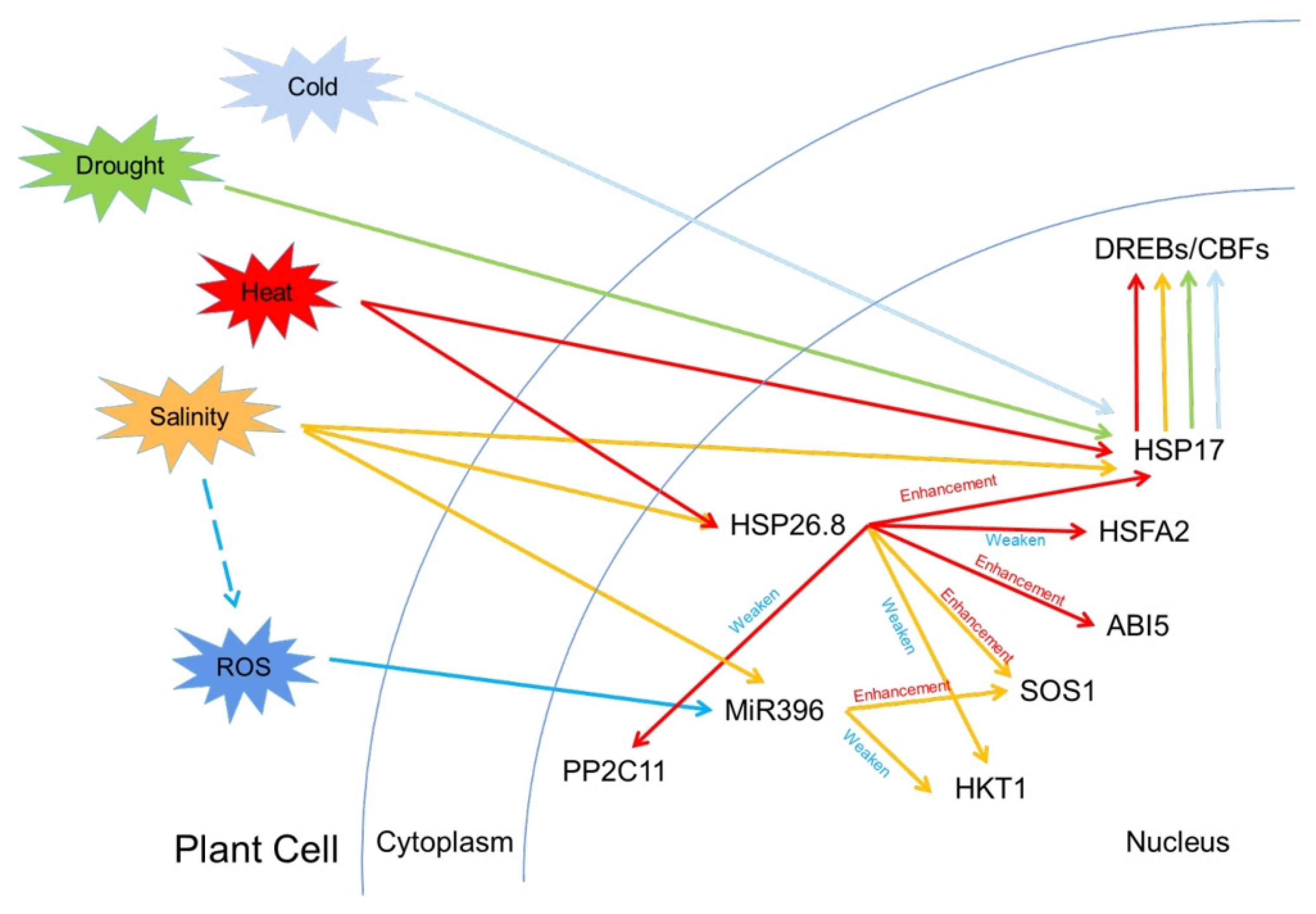

3.1. Heat Stress

3.2. Drought Stress

3.3. Saline-Alkali Stress

3.4. Heavy Metal Stress

4. Final Considerations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, N.; Lin, S.; Huang, B. Differential effects of glycine betaine and spermidine on osmotic adjustment and antioxidant defense contributing to improved drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2017, 142, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPaola, J.; Beard, J. Physiological effects of temperature stress. Turfgrass 1992, 32, 231–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bita, C.E.; Gerats, T. Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment: Scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.-J.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Shi, K.; Zhou, J.; Foyer, C.H.; Yu, J.-Q. Interplay between reactive oxygen species and hormones in the control of plant development and stress tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2839–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jespersen, D.; Yu, J.; Huang, B. Metabolite responses to exogenous application of nitrogen, cytokinin, and ethylene inhibitors in relation to heat-induced senescence in creeping bentgrass. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Huang, L.; Yan, Y. Exogenously applied spermidine improves drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass associated with changes in antioxidant defense, endogenous polyamines and phytohormones. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 76, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Skinner, D.; Liang, G.; Trick, H.; Huang, B.; Muthukrishnan, S. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of creeping bentgrass using GFP as a reporter gene. Hereditas 2001, 133, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Hu, Q.; Nelson, K.; Longo, C.; Kausch, A.; Chandlee, J.; Wipff, J.; Fricker, C. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) transformation using phosphinothricin selection results in a high frequency of single-copy transgene integration. Plant Cell Rep. 2004, 22, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonos, S.A.; Casler, M.D.; Meyer, W.A. Plant responses and characteristics associated with dollar spot resistance in creeping bentgrass. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Hsiang, T.; Li, J.; Luo, L. First report of dollar spot of Agrostis stolonifera, Poa pratensis, Festuca arundinacea and Zoysia japonica caused by Sclerotinia homoeocarpa in China. New Dis. Rep. 2011, 23, 2044-0588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.M. Management of Turfgrass Diseases; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bonos, S.A. Gene action of dollar spot resistance in creeping bentgrass. J. Phytopathol. 2011, 159, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, N.; Curley, J.; Warnke, S.; Casler, M.; Jung, G. Mapping QTL for dollar spot resistance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bonos, S.A.; Clarke, B.B.; Meyer, W.A. Breeding for disease resistance in the major cool-season turfgrasses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.; Powell, A.; Vincelli, P.; Dougherty, C. Dollar spot on bentgrass influenced by displacement of leaf surface moisture, nitrogen, and clipping removal. Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvalle, T.C.; Landschoot, P.J.; Kaminski, J.E. Effects of dew removal and mowing frequency on fungicide performance for dollar spot control. Plant Dis. 2011, 95, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.O.; Rogers, J.N.; Crum, J.R.; Vargas, J.M.; Nikolai, T.A. Effects of rolling and sand topdressing on dollar spot severity in fairway turfgrass. HortTechnology 2019, 29, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztur, E.D. Integrated Management of Dollar Spot Disease of Creeping Bentgrass Using Soil Conditioners. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiang, T.; Stone, K.; Rudland, M.; Chen, J. Non-conventional fungicides to control dollar spot disease. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2022, 14, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. Effect of watered-in demethylation-inhibitor fungicide and paclobutrazol applications on foliar disease severity and turfgrass quality of creeping bentgrass putting greens. Crop Prot. 2016, 79, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvin, J.W.; Kerr, R.A.; McCarty, L.B.; Bridges, W.; Martin, S.B.; Wells, C.E. Curative evaluation of biological control agents and synthetic fungicides for Clarireedia jacksonii. HortScience 2020, 55, 1622–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Earlywine, D.T.; Smeda, R.J.; Teuton, T.C.; English, J.T.; Sams, C.E.; Xiong, X. Effect of oriental mustard (Brassica juncea) seed meal for control of dollar spot on creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) Turf. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2017, 13, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, F.; Aşkın, A.; Koca, E.; Yıldırır, M. Identification, Genetic Diversity and Biological Control of Dollar Spot Disease Caused by Sclerotinia homoeocarpa on Golf Courses in Turkey. Int. J. Agric. For. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L.; Yin, Y.; Niu, Q.; Yan, X.; Yin, S. New insights into the mechanism of Trichoderma virens-induced developmental effects on Agrostis stolonifera disease resistance against Dollar spot infection. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Kaluwasha, W.; Xiong, X. Influence of calcium and nitrogen fertilizer on creeping bentgrass infected with dollar spot under cool temperatures. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2022, 14, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, R.; Millican, M.D.; Smith, D.; Nangle, E.; Hockemeyer, K.; Soldat, D.; Koch, P.L. Dollar spot suppression on creeping bentgrass in response to repeated foliar nitrogen applications. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanza, M.A.; Dernoeden, P.H. Brown patch severity in perennial ryegrass as influenced by irrigation, fungicide, and fertilizers. Crop Sci. 1996, 36, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, C.H.; Lyford, P.R. Use of fans and their effects on the turf microenvironment and disease development. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2022, 14, 1088–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Williams, D.; Wagner, G. Phylloplanins reduce the severity of gray leaf spot and brown patch diseases on turfgrasses. Crop Sci. 2011, 51, 2829–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.; Reis, M.; Guerrero, C.; Dionísio, L. Use of organic composts to suppress bentgrass diseases in Agrostis stolonifera. Biol. Control 2020, 141, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Hu, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Chen, C.-F.; Luo, H. Expression of a novel antimicrobial peptide Penaeidin4-1 in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) enhances plant fungal disease resistance. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cho, K.C.; Han, Y.J.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, S.S.; Hwang, O.J.; Song, P.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.I. Resistance to Rhizoctonia solani AG-2-2 (IIIB) in creeping bentgrass plants transformed with pepper esterase gene PepEST. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.; Vargas Jr, J.; Detweiler, A.; Dykema, N.; Yan, L. First report of a bacterial disease on creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) caused by Acidovorax spp. in the United States. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Investigating the Cause and Developing Management Options to Control Bacterial Etiolation in Creeping Bentgrass Putting Greens; North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.A.; Ma, B.; Tredway, L.P.; Ritchie, D.F.; Kerns, J.P. Identification and pathogenicity of bacteria associated with etiolation and decline of creeping bentgrass golf course putting greens. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.R. Identification and Characterization of a New Bacterial Disease of Creeping Bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) Caused by Acidovorax avenea subsp. Avenae; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mitkowski, N.; Browning, M.; Basu, C.; Jordan, K.; Jackson, N. Pathogenicity of Xanthomonas translucens from annual bluegrass on golf course putting greens. Plant Dis. 2005, 89, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Giordano, P.R.; Chaves, A.M.; Mitkowski, N.A.; Vargas, J.M., Jr. Identification, characterization, and distribution of Acidovorax avenae subsp. avenae associated with creeping bentgrass etiolation and decline. Plant Dis. 2012, 96, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Vargas, J.; Merewitz, E. Phytohormones associated with bacterial etiolation disease in creeping bentgrass. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 133, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Vargas, J.; Merewitz, E. Temperature and hormones associated with bacterial etiolation symptoms of creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 38, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Vargas, J.; Merewitz, E. Jasmonic and salicylic acid effects on bacterial etiolation and decline disease of creeping bentgrass. Crop Prot. 2018, 109, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Kerns, J.P.; Ritchie, D.F. Bacterial etiolation of creeping bentgrass as influenced by biostimulants and trinexapac-ethyl. Crop Prot. 2015, 72, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, P.J., Jr.; Horvath, B.; Kravchenko, A.; Vargas, J.M., Jr. Predicting Microdochium patch on creeping bentgrass. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2017, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, J.J.; Wilson, I.; Spencer-Phillips, P.T.; Arnold, D.L. Phosphite-mediated enhancement of defence responses in Agrostis stolonifera and Poa annua infected by Microdochium nivale. Plant Pathol. 2022, 71, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K. Efficacy of Non-Conventional Fungicides for Control of the Plant Pathogens Clarireedia jacksonii and Microdochium nivale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stricker, S.; Hsiang, T.; Bertrand, A. Reaction of bentgrass cultivars to a resistance activator and elevated CO2 levels when challenged with Microdochium nivale, the cause of Microdochium Patch. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2017, 13, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, B. Heat stress injury in relation to membrane lipid peroxidation in creeping bentgrass. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, B. Carbohydrate accumulation in relation to heat stress tolerance in two creeping bentgrass cultivars. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2000, 125, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkindale, J.; Huang, B. Changes of lipid composition and saturation level in leaves and roots for heat-stressed and heat-acclimated creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 51, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Huang, B. Lowering soil temperatures improves creeping bentgrass growth under heat stress. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 1878–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, M.; He, Y.; Huang, B. Leaf senescence and protein metabolism in creeping bentgrass exposed to heat stress and treated with cytokinins. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2007, 132, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.E.; Dernoeden, P.H. Dead spot severity, pseudothecia development, and overwintering of Ophiosphaerella agrostis in creeping bentgrass. Phytopathology 2006, 96, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanza, M.; Wetzel Iii, H.; Agnew, M.; Kaminski, J. Evaluation of fungicide and plant growth regulator tank-mix programmes on dollar spot severity of creeping bentgrass. Crop Prot. 2006, 25, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardella, P.A.; Tian, Z.; Clarke, B.B.; Belanger, F.C. The Epichloë festucae antifungal protein Efe-AfpA protects creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) from the plant pathogen Clarireedia jacksonii, the causal agent of dollar spot disease. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraisamy, K.; Ha, A.; Kim, J.; Park, A.R.; Kim, B.; Song, C.W.; Song, H.; Kim, J.-C. Enhancement of disease control efficacy of chemical fungicides combined with plant resistance inducer 2, 3-butanediol against turfgrass fungal diseases. Plant Pathol. J. 2022, 38, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settle, D.; Fry, J.; Tisserat, N. Effects of irrigation frequency on brown patch in perennial ryegrass. Int. Turfgrass Soc. Res. J. 2001, 9, 710–714. [Google Scholar]

- Smiley, R.W.; Dernoeden, P.; Clarke, B. Compendium of Turfgrass Diseases, 3rd ed.; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aamlid, T.S.; Espevig, T.; Tronsmo, A. Microbiological products for control of microdochium nivale on golf greens. Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Han, L.; Luo, H. AsHSP26. 8a, a creeping bentgrass small heat shock protein integrates different signaling pathways to modulate plant abiotic stress response. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Han, L.; Luo, H. AsHSP17, a creeping bentgrass small heat shock protein modulates plant photosynthesis and ABA-dependent and independent signalling to attenuate plant response to abiotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1320–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, B.; Banowetz, G. Cytokinin effects on creeping bentgrass responses to heat stress: I. Shoot and root growth. Crop Sci. 2002, 42, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.E.; Huang, B. Effects of trinexapac-ethyl foliar application on creeping bentgrass responses to combined drought and heat stress. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Goatley, M.; Wang, K.; Goddard, B.; Harvey, R.; Brown, I.; Kosiarski, K. Silicon Improves Heat and Drought Stress Tolerance Associated with Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Root Viability in Creeping Bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.). Agronomy 2024, 14, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Taylor, Z.; Goatley, M.; Wang, K.; Brown, I.; Kosiarski, K. Photosynthetic rate and root growth responses to Ascophyllum nodosum extract–based biostimulant in creeping bentgrass under heat and drought Stress. HortScience 2023, 58, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Huang, B. Protease inhibitors suppressed leaf senescence in creeping bentgrass exposed to heat stress in association with inhibition of protein degradation into free amino acids. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 102, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, B. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals common molecular factors responsive to heat and drought stress in Agrostis stolonifera. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Huang, B. Research advances in molecular mechanisms regulating heat tolerance in cool-season turfgrasses. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e21339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, M.; Vandenbrink, J.; Li, D.; Menchyk, N.; Reighard, S.; Norris, A.; Liu, H.; Sun, D. Heterologous expression of Os SIZ 1, a rice SUMO E 3 ligase, enhances broad abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013, 11, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, S.; Jia, H.; Gao, F.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, N.; Wu, P.; Hu, Q.; Sun, D.; Luo, H. Ectopic expression of a cyanobacterial flavodoxin in creeping bentgrass impacts plant development and confers broad abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Che, R.; Douglass, M.; Benza, K.; Angove, M.; Luo, K.; Hu, Q.; Chen, X. Gene pyramiding for boosted plant growth and broad abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Huang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Liang, G.H. Overexpression of barley hva1 gene in creeping bentgrass for improving drought tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, N.; Li, X.; Zhu, J.; Bian, X.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Hu, Q.; Luo, H. A chloroplast heat shock protein modulates growth and abiotic stress response in creeping bentgrass. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1769–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Peng, Y. Nitric oxide signal, nitrogen metabolism, and water balance affected by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in relation to enhanced tolerance to water stress in creeping bentgrass. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tang, M.; Cheng, B.; Han, L. Transcriptional regulation and stress-defensive key genes induced by γ-aminobutyric acid in association with tolerance to water stress in creeping bentgrass. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1858247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Yin, S. Mitigating effect of glycinebetaine pretreatment on drought stress responses of creeping bentgrass. HortScience 2018, 53, 1842–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, B.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, G.; Peng, Y. Spermine-mediated metabolic homeostasis improves growth and stress tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) under water or high-temperature stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 944358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Schmidt, R. Hormone-containing products’ impact on antioxidant status of tall fescue and creeping bentgrass subjected to drought. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 1344–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errickson, W.; Huang, B. Rhizobacteria-enhanced drought tolerance and post-drought recovery of creeping bentgrass involving differential modulation of leaf and root metabolism. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Huang, B. Differential proteomic responses to water stress induced by PEG in two creeping bentgrass cultivars differing in stress tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 1477–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Fiorentino, A.; Kuess, M.; Tharayil, N.; Kumar, R.; Leonard, E.; Noorai, R.; Hu, Q.; Luo, H. MicroRNA169 integrates multiple factors to modulate plant growth and abiotic stress responses. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2541–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zhuang, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, B. Transcriptional Regulation Mechanisms in AsAFL1-mediated Drought Tolerance for Creeping Bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswath, C.R.; Kim, S.H.; Mo, S.Y.; Kim, D.H. Transgenic plants of creeping bent grass harboring the stress inducible gene, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, are highly tolerant to drought and NaCl stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2005, 47, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, B. Transcriptional factors for stress signaling, oxidative protection, and protein modification in ipt-transgenic creeping bentgrass exposed to drought stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 144, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Luo, H. Role of microRNA319 in creeping bentgrass salinity and drought stress response. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 9, 1375–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Yang, C.; Zhu, L.; Luo, H. Constitutive expression of a miR319 gene alters plant development and enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1375–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, N.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Bethea, F.G., Jr.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Luo, H. Transgenic creeping bentgrass overexpressing Osa-miR393a exhibits altered plant development and improved multiple stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Yuan, N.; Zhou, M.; Xia, X.; Noorai, R.; Saski, C.; Li, S. MicroRNA396-mediated alteration in plant development and salinity stress response in creeping bentgrass. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Yuan, N.; Hu, Q.; Luo, H. Constitutive expression of rice microRNA528 alters plant development and enhances tolerance to salinity stress and nitrogen starvation in creeping bentgrass. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Baldwin, C.M.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Luo, H. Heterologous expression of Arabidopsis H+-pyrophosphatase enhances salt tolerance in transgenic creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Sun, X.; Ren, J.; Fan, J.; Lou, Y.; Fu, J.; Chen, L. Genetic diversity and association mapping of cadmium tolerance in bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers.]. Plant Soil 2015, 390, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladkov, E.; Gladkova, O.; Glushetskaya, L. Estimation of heavy metal resistance in the second generation of creeping bentgrass (Agrostis solonifera) obtained by cell selection for resistance to these contaminants and the ability of this plant to accumulate heavy metals. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2011, 47, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Bai, Y.; Chao, Y.; Sun, X.; He, C.; Liang, X.; Xie, L.; Han, L. Genome-wide analysis reveals four key transcription factors associated with cadmium stress in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.). PeerJ 2018, 6, e5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gururani, M.A.; Ganesan, M.; Song, I.-J.; Han, Y.; Kim, J.-I.; Lee, H.-Y.; Song, P.-S. Transgenic turfgrasses expressing hyperactive Ser599Ala phytochrome A mutant exhibit abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 35, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Pathogen | Symptoms | Prevention Measures | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dollar Spot | Clarireedia spp. | Small round, sunken, bleached, or straw-colored patches | Resistance materials: Declaration, Kingpin, Benchmark DSR, 007, 13M, HTM, HTL Physical control: removal of dew, sand cover, rolling. Chemical control: ferric sulfate/ferrous sulfate, azoxystrobin + propiconazole, triadimefon/paclobutrazol + fungicide, antifungal protein Efe-AfpA, mustard powder. Agricultural control: calcium fertilizer, nitrogen fertilizer Biological control: Pseudomonas putida 88cfp and 166fp, Bacillus cereus 44bac, Bacillus licheniformis | [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] |

| Brown Patch | Rhizoctonia solani | Brown or tan plaque | Physical control: Fan Chemical control: 2,3-butanediol, PepEST protein Agricultural control: Potassium Fertilization Biological control: T-phylloplanins, S-phylloplanins, Trichoderma atroviride | [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] |

| Bacterial Etiolation | Acidovorax avenae subsp. /Xanthomonas translucens /Pantoea ananatis | Leaf tip necrosis, wilting, yellowing and stem yellowing, electrolyte leakage in leaves and roots increased, chlorophyll content decreased and root activity decreased. | Chemical control: Salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, oxytetracycline, acibenzolar-S-methyl + chlorothalonil, trinexapac-ethyl | [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Microdochium patch | Microdochium nivale | Round, watery patches; leaves light gray, brown, white or grayish black, pink margin; pink mildew | Chemical control: Medallion, Headway, ferric sulfate, Civitas + Harmonizer, Phosphite Biological control: Turf WPG, Turf S+ | [47,48,49,50,51] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, M.; Li, M.; Ren, X.; Wang, X. Resistance of Creeping Bentgrass to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: A Model System for Grass Stress Biology. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122761

Ren Z, Sun X, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Yuan M, Li M, Ren X, Wang X. Resistance of Creeping Bentgrass to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: A Model System for Grass Stress Biology. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122761

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Zhuang, Xinbo Sun, Yalin Chen, Yaxi Zhang, Meng Yuan, Mengyu Li, Xiaopeng Ren, and Xiaodong Wang. 2025. "Resistance of Creeping Bentgrass to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: A Model System for Grass Stress Biology" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122761

APA StyleRen, Z., Sun, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Yuan, M., Li, M., Ren, X., & Wang, X. (2025). Resistance of Creeping Bentgrass to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: A Model System for Grass Stress Biology. Agronomy, 15(12), 2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122761