Bioaccumulation, Gender-Specific Differences, and Biomagnification of Heavy Metals Through a Tri-Trophic Chain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Model

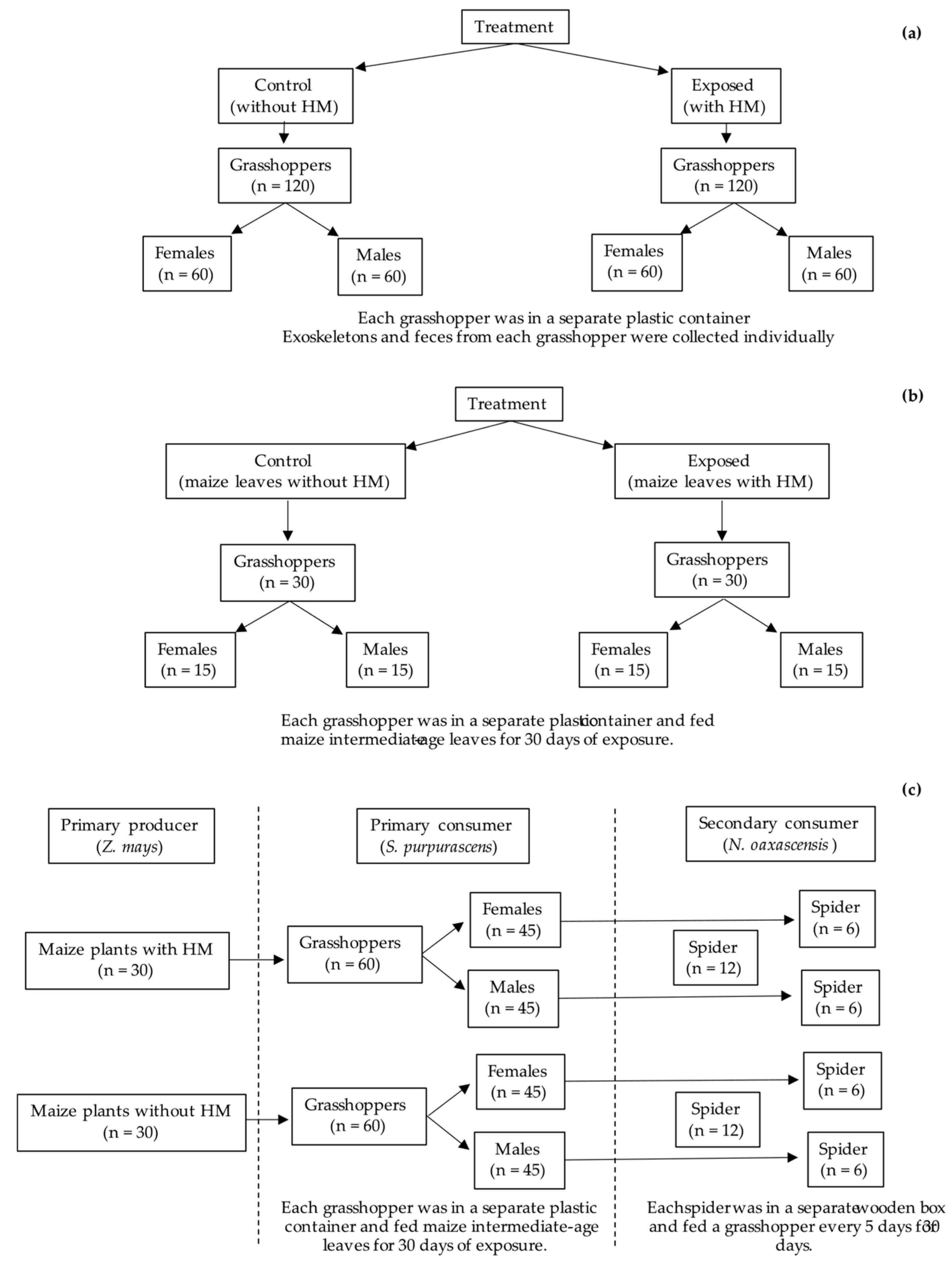

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Body Biomass of Grasshopper Sphenarium purpurascens and Percentage of Maize Leaf Material Consumed with and Without Heavy Metals

2.3.2. Maize with Metals (Primary Producer)—Grasshopper (Primary Consumer)—Spider (Secondary Consumer)

2.4. Heavy Metal Concentrations in Maize, Grasshoppers, and Spider Tissues

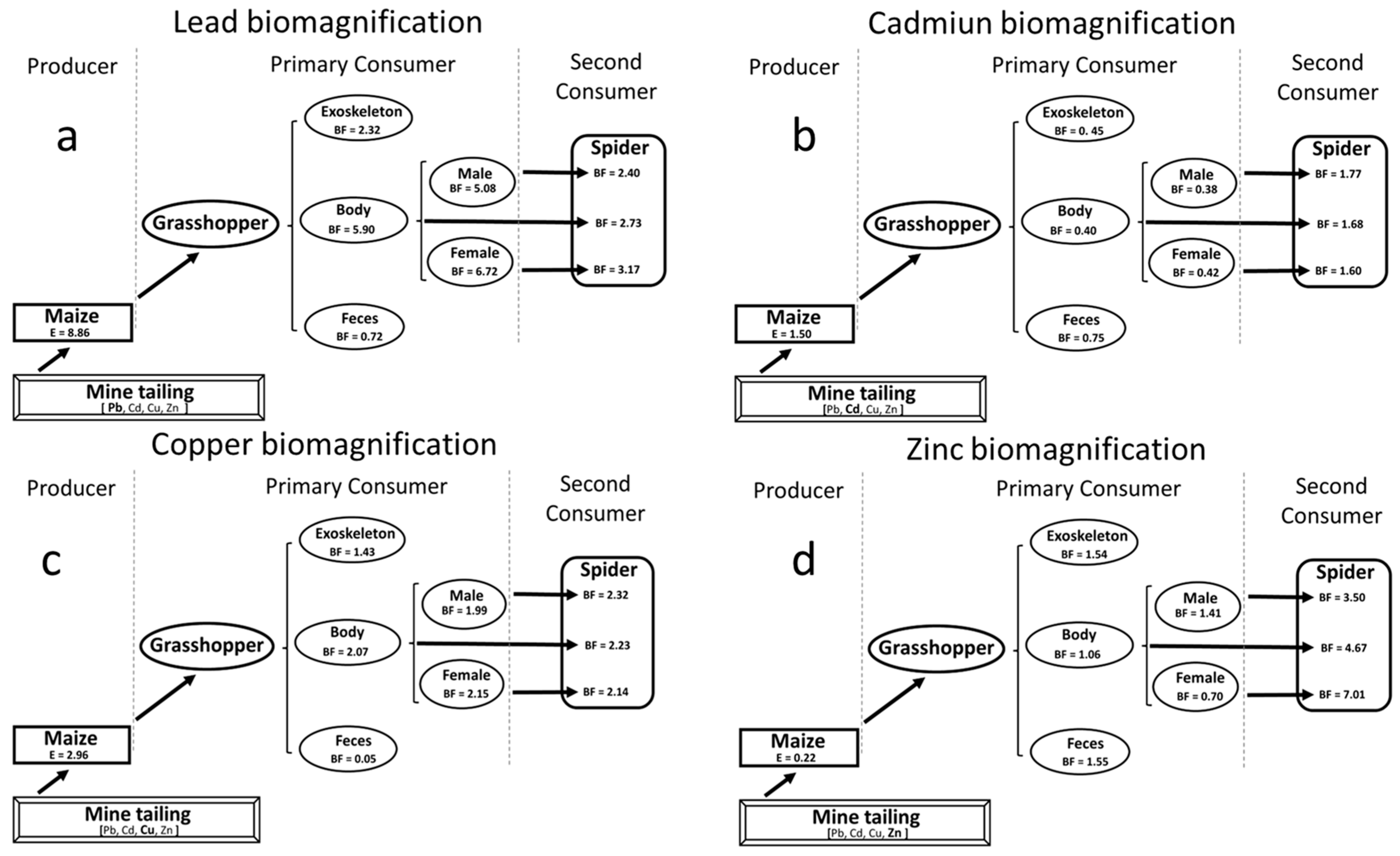

2.5. Bioconcentration Factor (BCF) and Biomagnification Factor (BMF)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biomass, Bioccumulation, Gender-Specific Differences, and Biomagnification of Heavy Metals Through a Tri-Trophic Chain

3.2. Heavy Metal Concentrations in Maize, Grasshoppers, and Spiders’ Tissues

4. Discussion

4.1. Body Biomass of the Grasshopper Sphenarium purpurascens and Percentage of Maize Leaf Material Consumed with and Without Heavy Metals

4.2. Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation in Females and Males of Sphenarium purpurascens

4.3. Heavy Metal Concentrations in Maize, Grasshoppers, and Spiders’ Tissues

4.4. Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms Implicated in Heavy Metals Bioaccumulation and Their Trophic Transference

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía), Economía y Sectores Productivos: Minería. 2025. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mineria/#informacion_general (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía), Información Demográfica y Social: Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (ENOE), Población de 15 Años y Más de Edad. 2024. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enoe/15ymas/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- SE (Secretaría de Economía), Minería. 2024. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/se/acciones-y-programas/mineria (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Covarrubias, S.A.; Cabriales, J.J.P. Contaminación ambiental por metales pesados en México: Problemática y estrategias de fitorremediación. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2017, 33, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, T.J.A.; De la Rosa, P.D.A.; Ramírez, I.M.E.; Volke, S.T. Evaluación de Tecnologías de Remediación Para Suelos Contaminados con Metales, Etapa II; Secretaria del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: Mexico City, Mexico, 2005; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo-Martínez, M.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Hernández-Plata, I.; Valencia-Cuevas, L.; Rodríguez, A.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. Phytoremediation potential of Crotalaria pumila (Fabaceae) in soils polluted with heavy metals: Evidence from field and controlled experiments. Plants 2024, 13, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Flores, M. Evaluación de la Concentración y Biodisponibilidad de Metales Pesados en Residuos Mineros de Huautla, Morelos. Bachelor Thesis, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Santoyo-Martínez, M.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Hernández-Plata, I.; Valencia-Cuevas, L.; Flores-Morales, A.; Ortiz-Hernández, L.; Flores-Trujillo, K.; Ramos-Quintana, F.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. Heavy metal bioaccumulation and morphological changes in Vachellia campechiana (Fabaceae) reveal its potential for phytoextraction of Cr, Cu, and Pb in mine tailings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 11260–11276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves-Aguilar, J.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Valencia-Cuevas, L.; García-Cigarrero, A.A.; Rodríguez, A.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. Ecotoxicological effects of heavy metal bioaccumulation in two trophic levels. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 49840–49855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E. Trophic transfer, bioaccumulation, and biomagnification of non-essential hazardous heavy metals and metalloids in food chains/webs—Concepts and implications for wildlife and human health. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2019, 25, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobritzsch, D.; Grancharov, K.; Hermsen, C.; Krauss, G.-J.; Schaumlöffel, D. Inhibitory effect of metals on animal and plant glutathione transferases. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 57, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, A.; Govarthanan, M.; Karmegam, N.; Biruntha, M.; Kumar, D.S.; Arthanari, M.; Govindarajan, R.K.; Tripathi, S.; Ghosh, S.; Kumar, P.; et al. Metallothionein dependent-detoxification of heavy metals in the agricultural field soil of industrial area: Earthworm as field experimental model system. Chemosphere 2021, 267, 129240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodchild, C.G.; Simpson, A.M.; Minghetti, M.; DuRant, S.E. Bioenergetics-adverse outcome pathway: Linking organismal and suborganismal energetic endpoints to adverse outcomes. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019, 38, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, R.K.; Prosser, R.S. Bioaccumulation and maternal transfer of copper in the freshwater snail Planorbella pilsbryi. Ecotoxicology 2025, 34, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipovic-Trajkovic, R.; Ilic, Z.; Šunić, L.; Andjelkovic, S. The potential of different plant species for heavy metals accumulation and distribution. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 959–964. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, P.K.; Uddin, M.d.N.; Ara, M.H.; Tonu, N.T. Heavy metals concentration in vegetables, fruits and cereals and associated health risk of human in Khulna. Bangladesh, J. Wat. Env. Sci. 2019, 3, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Gismondi, E.; Cossu-Leguille, C.; Beisel, J.N. Do male and female gammarids defend themselves differently during chemical stress? Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 140–141, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázová, T.; Syrota, Y.; Oros, M.; Uhrovič, D. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Freshwater Fish: The Role of Species, Age, Gender, and Parasites. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 114, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gade, M.; Comfort, N.; Re, D.B. Sex-specific neurotoxic effects of heavy metal pollutants: epidemiological, experimental evidence and candidate mechanisms. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, M.S.; Kindra, M.; Dargent, F.; Hu, L.; Flockhart, D.T.T.; Norris, D.R.; Kharouba, H.; Talavera, G.; Bataille, C.P. Metals and metal isotopes incorporation in insect wings: Implications for geolocation and pollution exposure. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1085903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, L. Trophic transfer of trace elements. In Encyclopedia of Aquatic Ecotoxicology; Férard, J.-F., Blase, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1171–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba-Tóvar, L.; Marrugo-Negrete, J.; Barón, P.R.; Díez, S. Drivers of biomagnification of Hg, as and Se in aquatic food webs: A review. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 112226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, J.E.; Boyd, R.S.; Rajakaruna, N. Transfer of heavy metals through terrestrial food webs: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibbett, M.; Green, I.; Rate, A.; De Oliveira, V.H.; Whitaker, J. The transfer of trace metals in the soil-plant-arthropod system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, T.; Greyvenstein, B.; Silva, J.; Siebert, S.J. Transfer of potentially toxic metals and metalloids from terrestrial plants to arthropods—A mini review. Ecol. Res. 2024, 39, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Razas de Maíz de México. Biodiversidad Mexicana. 2022. Available online: https://bioteca.biodiversidad.gob.mx/janium/Documentos/Graficos/16327.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Vergara-Allende, C.A. Biocumulación de Metales Pesados y Daño Genotóxico en Cultivos de Traspatio Zea mays (Raza Pepitilla) en Suelos Expuestos a Jales Mineros, en Huautla, Morelos: Base Para Generar una Propuesta de Mitigación. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos Vargas, I.; Cano Santana, Z. Variaciones ecomorfológicas de las ootecas de Sphenarium purpurascens Charpentier (Orthoptera: Pygomorphidae) en un matorral xerófilo del centro de México. Folia Entomol. Mex. 2017, 3, 54–69. Available online: https://revistas.acaentmex.org/index.php/folia/article/view/132 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Castellanos-Vargas, I.; Cano-Santana, Z. Historia natural y Ecología de Sphenarium purpurascens (Orthoptera: Pyrgomorphidae). In Biodiversidad del Ecosistema del Pedregal de San Ángel; Lot., A., Cano-Santana., Z., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009; pp. 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Peng, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, Z. Spiders as excellent experimental models for investigation of heavy metal impacts on the environment: A review. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, O.; Arias, D.; Ramírez, R.; Sousa, M. Leguminosas de la Sierra de Huautla; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Centro de Educación Ambiental e Investigación Sierra de Huautla: Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2005; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, Compendio de información geográfica municipal, Tlaquiltenango, Morelos. 2010. Available online: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/17/17025.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Acosta-Núñez, L.F.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Rodríguez-Solís, A.; Castañeda-Espinoza, J.D.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. In situ phytoremediation of mine tailings with high concentrations of cadmium and lead using Dodonaea viscosa (Sapindaceae). Plants 2025, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Santana, Z. Identificación de los estadios de desarrollo de Sphenarium purpurascens Charpentier (Orthoptera: Pyrgomrphidae) por el tamaño de su cabeza. Folia Entomol. Mex. 1997, 100, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, H.W. American Neoscona and corrections to previous revisions of Neotropical orb-weavers (Araneae: Araneidae). Psyche 1993, 99, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, L. Accumulation of Pb, Cu, and Zn in native plants growing on a contaminated Florida site. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarsan, E.; Yipel, M. The important terms of marine pollution “biomarkers and biomonitoring, bioaccumulation, bioconcentration, biomagnification”. J. Mol. Biomark. Diagn. 2013, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J. Biostatistical Analysis; Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 944. [Google Scholar]

- Soft. Correspondence Analysis. Tulsa, StatSoft Inc. 2007. Available online: http://www.statsoftinc.com/textbook/stcoran.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Amadio, M.E.; Pietrantuono, A.L.; Lozada, M.; Fernández-Arhex, V. Effect of plant nutritional traits on the diet of grasshoppers in a wetland of Northern Patagonia. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2020, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.L.; Yin, Y.; Li, S.S.; Li, M.Q.; Tajdar, A.; Tan, S.Q.; Shi, W.P. Chemical composition and amino acids of Locusta migratoria (Orthoptera Acrididae) fed wheat seedlings (Triticum aestivum) or rape leaves (Brassica napus). J. Insects Food Feed 2024, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, L.E.; Lozano, E.; Gárate, A.; Carpena, R. Influence of cadmium on the uptake, tissue accumulation and subcellular distribution of manganese in pea seedlings. Plant Sci. 1998, 132, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, M.; Adesanwo, O.; Adepetu, J. Effect of copper (Cu) application on soil available nutrients and uptake. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 10, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yamaji, N.; Ma, J.F. Metal Transport Systems in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.A.; Qamar, Z.; Waqas, M. The uptake and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by food plants, their effects on plants nutrients, and associated health risk: A review. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2015, 22, 13772–13799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawęda, M. Changes in the contents of some carbohydrates in vegetables, cumulating lead. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2007, 16, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Widowati, H. The influence of cadmium heavy metal on vitamins in aquatic vegetables. Makara J. Sci. 2012, 16, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guédard, M.; Faure, O.; Bessoule, J.-J. Early changes in the fatty acid composition of photosynthetic membrane lipids from Populus nigra grown on a metallurgical landfill. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzuroglu, O.; Obek, E.; Karatas, F.; Tatar, S.Y. Effects of simulated acid rain on vitamins A, E, and C in strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Pak. J. Nutr. 2005, 4, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinasabapathi, B.; Rangasamy, M.; Froeba, J.; Cherry, R.H.; McAuslane, H.J.; Capinera, J.L.; Srivastava, M.; Ma, L.Q. Arsenic hyperaccumulation in the Chinese brake fern (Pteris vittata) deters grasshopper (Schistocerca americana) herbivory. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ullah, M.I.; Saeed, M.F.; Khalid, S.; Saqib, M.; Arshad, M.; Afzal, M.; Damalas, C.A. Heavy metal exposure through artificial diet reduces growth and survival of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 14426–14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Zhang, Z.T.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y. Effects of the metals lead and zinc on the growth, development, and reproduction of Pardosa astrigera (Araneae: Lycosidae). Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 86, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhafar, Z.M.; Sharaby, A. Effect of zinc sulfate against the red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus with reference to their histological changes on the larval midgut and adult reproductive system. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2012, 2, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, J.; Sharma, M.; Wani, K.A. Heavy metals in vegetables and their impact on the nutrient quality of vegetables: A review. J. Plant Nutr. 2018, 41, 1744–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldbauer, G.P. The Consumption and Utilization of Food by Insects. In Advances in Insect Physiology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1968; Volume 5, pp. 229–288. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, K.; Ohsaki, N. Examination of the food processes on mixed inferior host plants in a polyphagous grasshopper. Popul. Ecol. 2006, 48, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B.A.; Hunter, L.M.; Johnson, M.S.; Thompson, D.J. Dynamics of metal accumulation in the Grasshopper Chorthippus brunneus in contaminated grasslands. Arco. Reinar. Contam. Toxicol. 1987, 16, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.A.; Lepp, N.W.; Hodkinson, I.D. Accumulation and egestion of dietary copper and cadmium by the grasshopper Locusta migratoria R&F (Orthoptera: Arcididae). Environ. Pollut. 1996, 92, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devkota, B.; Schmidt, G.H. Accumulation of heavy metals in food plants and grasshoppers from the Taigetos Mountains, Greece. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 78, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Chardi, A.; Ribeiro, C.A.O.; Nadal, J. Metals in liver and kidneys and the effects of chronic exposure to pyrite mine pollution in the shrew Crocidura russula inhabiting the protected wetland of Doñana. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, M.; Babczyńska, A.; Augustyniak, M. Oxidative stress in newlyhatched Chorthippus brunneus—the effects of zinc treatment during diapause, depending on the female’s age and its origins. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 2011, 154, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heliövaara, K.; Väisänen, R.; Kemppi, E.; Lodenius, M. 1990. Heavy metal concentrations in males and females of three pine diprionids (Hymenoptera). Entomol. Fennica 1990, 4, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, Y.; Yang, W. Functions of essential nutrition for high quality spermatogenesis. ABB 2011, 2, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathke, C.; Baarends, W.M.; Awe, S.; Renkawitz-Pohl, R. Chromatin dynamics during spermiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2014, 1839, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migula, P.; Przybylowicz, W.J.; Nakonieczny, M.; Augustyniak, M.; Tarnawska, M.; Mesjasz-Przybylowicz, J. Micro-PIXE studies of Ni-elimination strategies in representatives of two families of beetles feeding on Ni hyperaccumulating plant Berkheya coddii. X-Ray Spectrom. 2011, 40, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, D.V.; Bura, M.; Gergen, I.; Harmanescu, M.; Bordean, D. Bioaccumulative and conchological assessment of heavy metal transfer in a soil-plant-snail food chain. Chem. Cen. J. 2012, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, D.J.; Luoma, S.N.; Wallace, W.G. Linking metal bioaccumulation of aquatic insects to their distribution patterns in a mining-impacted river. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2004, 23, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gekière, A. Terrestrial insect defences in the face of metal toxicity. Chemosphere 2025, 372, 144091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, E.; Tóthmérész, B.; Kis, O.; Jakab, T.; Eva Szalay, P.; Vincze, A.; Baranyai, E.; Harangi, S.; Miskolczi, M.; Dévai, G. Environmental-friendly contamination assessment of habitats based on the trace element content of dragonfly exuviae. Agua 2019, 11, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylowicz, W.J.; Mesjasz-Przybylowicz, J.; Migula, P.; Glowacka, E.; Nakonieczny, M.; Augustyniak, M. Functional analysis of metals distribution in organs of the beetle Chrysolina pardalina exposed to excess of nickel by Micro-PIXE. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 2003, 210, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Zhuang, P.; Li, Z.; Xia, H.; Lu, H. Accumulation and detoxification of cadmium by larvae of Prodenia litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) feeding on Cd-enriched amaranth leaves. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, H.R.; Kortje, K.H.; Alberti, G. Content, absorption quantities and intracellular storage sites of heavy metals in Diplopoda (Arthropoda). BioMetals 1995, 8, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek, M.; Dąbrowski, J.; Różański, S.; Janicki, B.; Długosz, J. Heavy Metals Bioaccumulation in Tissues of Spiny-Cheek Crayfish (Orconectes limosus) from Lake Gopło: Effect of Age and Sex. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2017, 98, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.; Zou, E. Cadmium is deposited to the exoskeleton during post-ecdysial mineralization in the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 798, 149358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.E.A.; Armienta, M.A. Acumulación de arsénico y metales pesados en maíz en suelos cercanos a jales o residuos mineros. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2012, 28, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Izasa-Guzmán, G. Efecto del plomo sobre la inhibición, germinación y crecimiento de Phaseolus vulgaris L. y Zea mays L. Biotecnol. Veg. 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Munive Cerrón, R.; Loli Figueroa, O.; Azabache Leyton, A.; Gamarra Sánchez, G. Fitorremediación con maíz (Zea mays L.) y compost de Stevia en suelos degradados por contaminación con metales pesados. Sci. Agropecu. 2018, 9, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeros-Márquez, O.; Tejo-Calzada, R.; Reveles-Hernández, M.; Valdez-Cepeda, R.D.; Arreola-Ávila, J.G.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Ruíz-Torres, J. Uso potencial del huizache (Acacia farnesiana L. Will) en la fitorremediación de suelos contaminados con plomo. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Ambient. 2011, 17, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Ramírez, L.T.; Ramírez-López, M.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Ortiz-Hernández, M.L.; Sánchez-Salinas, E.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. Heavy metal biomagnification and genotoxic damage in two trophic levels exposed to mine tailings: A network theory approach. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2018, 91, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Ramírez, M.; Tovar-Sánchez, E.; Rodríguez-Solís, A.; Flores-Trujillo, K.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Mussali-Galante, P. Assisted phytoremediation between biochar and Crotalaria pumila to phytostabilize heavy metals in mine tailings. Plants 2024, 13, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussali-Galante, P.; Gómez-Arroyo, S.; Rodríguez-Solís, A.; Valencia-Cuevas, L.; Flores-Márquez, A.R.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. Multi-biomarker approach reveals the effects of heavy metal bioaccumulation in the foundation species Prosopis laevigata (Fabaceae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 47116–47131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wu, L. Effects of copper concentration on mineral nutrient uptake and copper accumulation in protein of coppertolerant and nontolerant Lotus purshianus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1994, 29, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardea-Torresdey, J.; Peralta-Videa, J.; Montes, M.; de la Rosa, G.; Corral-Diaz, B. Bioaccumulation of cadmium, chromium and copper by Convolvulus arvensis L.: Impact on plant growth and uptake of nutritional elements. Bioresour. Technol. 2004, 92, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, G.; Babczyńska, A.; Augustyniak, M.; Doleżych, B.; Migula, P.; Młyńska, H. Relations between metals (Zn, Pb, Cd and Cu) and glutathione-dependent detoxifying enzymes in spiders from a heavy metal pollution gradient. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 132, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migula, P.; Wilczek, G.; Babczynska, A. Effects of heavy metal contamination. In Spider Ecophisiology; Wolfgang, N., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, L. Accumulation of cadmium, copper, and zinc in five species of phytophagous insects. Environ. Entomol. 1992, 21, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Camenzuli, L.; Van Der Lee, M.K.; Oonincx, D.G.A.B. Uptake of cadmium, lead and arsenic by Tenebrio molitor and Hermetia illucens from contaminated substrates. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.; Santos, C.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Mann, R.M. Does subcellular distribution in plants dictate the trophic bioavailability of cadmium to Porcellio dilatatus (Crustacea, Isopoda). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, R.M.; Vijver, M.G.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Metals and Metalloids in Terrestrial Systems: Bioaccumulation, Biomagnification and Subsequent Adverse Effects. In Ecological Impacts of Toxic Chemicals; Sánchez-Bayo, F., van den Brink, P.J., Mann, R., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: Dubai, UAE, 2011; pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Merrington, G.; Miller, D.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Keller, M.A. Trophic barriers to fertilizer Cd bioaccumulation through the food chain: A case study using a plant-insect predator pathway. Arch Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, I.D.; Merrington, G.; Tibbett, M. Transfer of cadmium and zinc from sewage sludge amended soil through a plantaphid system to newly emerged adult ladybirds (Coccinella septempunctata). Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 99, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, G.; Babczyńska, A.; Wilczek, P.; Doleżych, B.; Migula, P.; Młyńska, H. Cellular stress reactions assessed by gender and species in spiders from areas variously polluted with heavy metals. Ecotoxical. Environ. Saf. 2008, 70, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schipper, A.M.; Wijnhoven, S.; Leuven, R.S.; Ragas, A.M.; Hendriks, A.J. Spatial distribution and internal metal concentrations of terrestrial arthropods in a moderately contaminated lowland floodplain along the Rhine river. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 151, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, F.; Maelfait, J.P.; Langenbick, F. Absence of cadmium excretion and high assimilation result in cadmium biomagnification in a wolf spider. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2003, 55, 287e292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, G.; Yang, M.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Song, S.; Ma, E.; Guo, Y. Chronic accumulation of cadmium and its effects on antioxidant enzymes and malondialdehyde in Oxya chinensis (Orthoptera: Acridoidea). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.C.S.; dos Santos, A.S.; dos Santos Santana, T.; Winkaler, E.U.; Lhano, M.G. Activity of biochemical biomarkers in grasshoppers Abracris flavolineata (De Geer, 1773) (Orthoptera: Acrididae: Ommatolampidinae). Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e409101119877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Waseem, M.; Ullah, S.; Arshad, R.; Akram, A. A review of heavy metals bioaccumulation in insects for environmental monitoring. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2025, 86, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Finet, C.; Cong, H.; Wei, H.Y.; Chung, H. The evolution of insect metallothioneins. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20202189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalakshmi, K.S.V.; Liu, W.C.; Balamuralikrishnan, B.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Sattanathan, G.; Pappuswamy, M.; Joseph, K.S.; Lee, J.W. Cadmium as an endocrine disruptor that hinders the reproductive and developmental pathways in freshwater fish: A review. Fishes 2023, 8, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M. Insect excretory mechanisms. Adv. Insect Physiol. 2008, 35, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, P.; Bedini, S.; Conti, B. Multiple functions of Malpighian tubules in insects: A review. Insects 2022, 13, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.B.; Zou, X.P.; Zhang, N.; Feng, Q.L.; Zheng, S.C. Detoxification of insecticides, allechemicals and heavy metals by glutathione S-transferase SlGSTE1 in the gut of Spodoptera litura. Insect Sci. 2015, 22, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, D.; Wang, G.; He, Q.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhao, P. Adaptive changes in detoxification metabolism and transmembrane transport of Bombyx mori malpighian tubules to artificial diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.A.; Willi, Y. Detecting genetic responses to environmental change. Nat. Rev. Gen. 2008, 9, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.C. Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology: The Science of Pollution, 5th. ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; p. 458. [Google Scholar]

- Majlesi, S.; Roivainen, P.; Kasurinen, A.; Tuovinen, T.; Juutilainen, J. Transfer of elements from soil to earthworms and ground beetles in boreal forest. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2023, 62, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Bejarano, P.I.; Puente-Rivera, J.; Cruz-Ortega, R. Metal and metalloid toxicity in plants: An overview on molecular aspects. Plants 2021, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, U.; Khan, S.M.; Khalid, N.; Ahmad, Z.; Jehangir, S.; Fatima Rizvi, Z.; Lho, L.H.; Han, H.; Raposo, A. Detoxifying the heavy metals: A multipronged study of tolerance strategies against heavy metals toxicity in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1154571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Prasad, M.N.V. Plant-lead interactions: Transport, toxicity, tolerance, and detoxification mechanisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 166, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Stoleru, V.; Gavrilescu, M. Analysis of heavy metal impacts on cereal crop growth and development in contaminated soils. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, C.; Rodríguez-Celma, J.; Kraemer, U.; Sanders, D.; Balk, J. The BRUTUS-LIKE E3 ligases BTSL1 and BTSL2 fine-tune transcriptional responses to balance Fe and Zn homeostasis. bioRxiv 2022, 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiello, E.M.; Ruiz, H.A.; Neves, J.C.L.; Ventrella, M.C.; Araújo, W.L. Zinc deficiency affects physiological and anatomical characteristics in maize leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 183, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mleczek, M.; Budka, A.; Gąsecka, M.; Budzyńska, S.; Drzewiecka, K.; Magdziak, Z.; Rutkowski, P.; Goliński, P.; Niedzielski, P. Copper, Lead and zinc interactions during phytoextraction using Acer platanoides L.—A Pot trial. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 27191–27207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutrowska, A.; Małecka, A.; Piechalak, A.; Masiakowski, W.; Hanć, A.; Barałkiewicz, D.; Andrzejewska, B.; Zbierska, J.; Tomaszewska, B. Effects of binary metal combinations on zinc, copper, cadmium and lead uptake and distribution in Brassica juncea. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 44, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, M.; Li, R.; Shen, X.; Yu, L.; Han, J. Multiple heavy metals affect root response, iron plaque formation, and metal bioaccumulation of Kandelia Obovata. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Song, Z.; Liu, W.; Lyu, B. Molecular and proteomic analyses of effects of cadmium exposure on the silk glands of Trichonephila clavata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wen, L.; Wang, L.; Zheng, C.; Yuan, Z.; Li, C. Influence of lead exposure on growth and transcriptome in wolf spider Pardosa laura. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2024, 27, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, Q.-s. Integrated transcriptome and proteome unveiled distinct toxicological effects of long-term cadmium pollution on the silk glands of Pardosa pseudoannulata. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site/Treatment | pH | EC (dS∙cm−1) | OM (%) | Texture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quilamula (without metals) | 6.58–6.71 | 0.21–0.25 | 6.45–7.04 | clay loam |

| Mine tailing (with metals) | 7.52–7.85 | 0.18–0.19 | 0.46–0.52 | clay loam |

| Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metal | Female | Male | Student t-test |

| Treatment without HMs | |||

| Pb | ND | ND | |

| Cd | ND | ND | |

| Cu | 3.18 ± 0.08 | 2.89 ± 0.35 | 3.182 ** |

| Zn | 22.98 ± 3.15 | 29.61 ± 6.60 | 3.511 ** |

| Treatment with HMs | |||

| Pb | 313.90 ± 32.50 | 415.12 ± 82.26 | 4.435 *** |

| Cd | 5.25 ± 1.23 | 4.74 ± 1.39 | 1.060 n.s. |

| Cu | 51.16 ± 9.78 | 47.26 ± 12.45 | 0.953 n.s. |

| Zn | 65.90 ± 33.25 | 131.93 ± 24.00 | 6.236 *** |

| Trophic Level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metal | Mine Tailing | Producer (Z. mays) | Primary Consumer (S. purpurascens) | Secondary Consumer (N. oaxacensis) | F2,63 | |||

| Treatment without HMs | ||||||||

| Pb | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| Cd | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| Cu | 2.12 ± 0.34 | a | 3.04 ± 5.41 | b | 6.33 ± 0.83 | c | 336.086 *** | |

| Zn | 23.14 ± 6.54 | a | 26.29 ± 6.10 | ab | 30.427 ± 0.44 | b | 4.572 ** | |

| Treatment with HMs | ||||||||

| Pb | 6.97 | 61.80 ± 4.45 | a | 364.55 ± 80.19 | b | 994.59 ± 156.99 | c | 477.666 *** |

| Cd | 8.37 | 12.56 ± 6.54 | a | 5.00 ± 0.95 | b | 8.41 ± 0.95 | a | 97.943 *** |

| Cu | 8.02 | 23.74 ± 3.15 | a | 49.21 ± 11.18 | b | 109.60 ± 8.21 | c | 288.416 *** |

| Zn | 428.11 | 93.75 ± 23.47 | a | 98.92 ± 44.04 | a | 461.69 ± 76.90 | b | 225.466 *** |

| Heavy Metal | Body | Exoskeleton | Feces | F2,87 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment without HMs | |||||||

| Pb | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Cd | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||

| Cu | 3.04 ± 5.41 | a | 2.32 ± 0.78 | b | 0.78 ± 0.13 | c | 108.466 *** |

| Zn | 26.29 ± 6.10 | a | 32.83 ± 4.93 | b | 16.07 ± 5.61 | c | 45.585 *** |

| Treatment with HMs | |||||||

| Pb | 364.550 ± 80.193 | a | 143.491 ± 20.070 | b | 44.667 ± 3.615 | c | 352.630 *** |

| Cd | 4.997 ± 0.947 | a | 5.705 ± 0.854 | a | 9.463 ± 1.511 | b | 109.392 *** |

| Cu | 49.213 ± 11.178 | a | 34.015 ± 7.312 | b | 1.135 ± 0.438 | c | 480.164 *** |

| Zn | 98.915 ± 44.037 | a | 143.926 ± 10.826 | b | 145.076 ± 16.902 | b | 26.630 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rebollo-Salinas, D.B.; Mussali-Galante, P.; Valencia-Cuevas, L.; Cano-Santana, Z.; Rodríguez, A.; Castrejón-Godínez, M.L.; Tovar-Sánchez, E. Bioaccumulation, Gender-Specific Differences, and Biomagnification of Heavy Metals Through a Tri-Trophic Chain. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122762

Rebollo-Salinas DB, Mussali-Galante P, Valencia-Cuevas L, Cano-Santana Z, Rodríguez A, Castrejón-Godínez ML, Tovar-Sánchez E. Bioaccumulation, Gender-Specific Differences, and Biomagnification of Heavy Metals Through a Tri-Trophic Chain. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122762

Chicago/Turabian StyleRebollo-Salinas, Dania Berenice, Patricia Mussali-Galante, Leticia Valencia-Cuevas, Zenón Cano-Santana, Alexis Rodríguez, María Luisa Castrejón-Godínez, and Efraín Tovar-Sánchez. 2025. "Bioaccumulation, Gender-Specific Differences, and Biomagnification of Heavy Metals Through a Tri-Trophic Chain" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122762

APA StyleRebollo-Salinas, D. B., Mussali-Galante, P., Valencia-Cuevas, L., Cano-Santana, Z., Rodríguez, A., Castrejón-Godínez, M. L., & Tovar-Sánchez, E. (2025). Bioaccumulation, Gender-Specific Differences, and Biomagnification of Heavy Metals Through a Tri-Trophic Chain. Agronomy, 15(12), 2762. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122762