Proline-Rich Specific Yeast Derivatives Enhance Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Water Status and Enable Reduced Irrigation Volumes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Layout and Weather Conditions

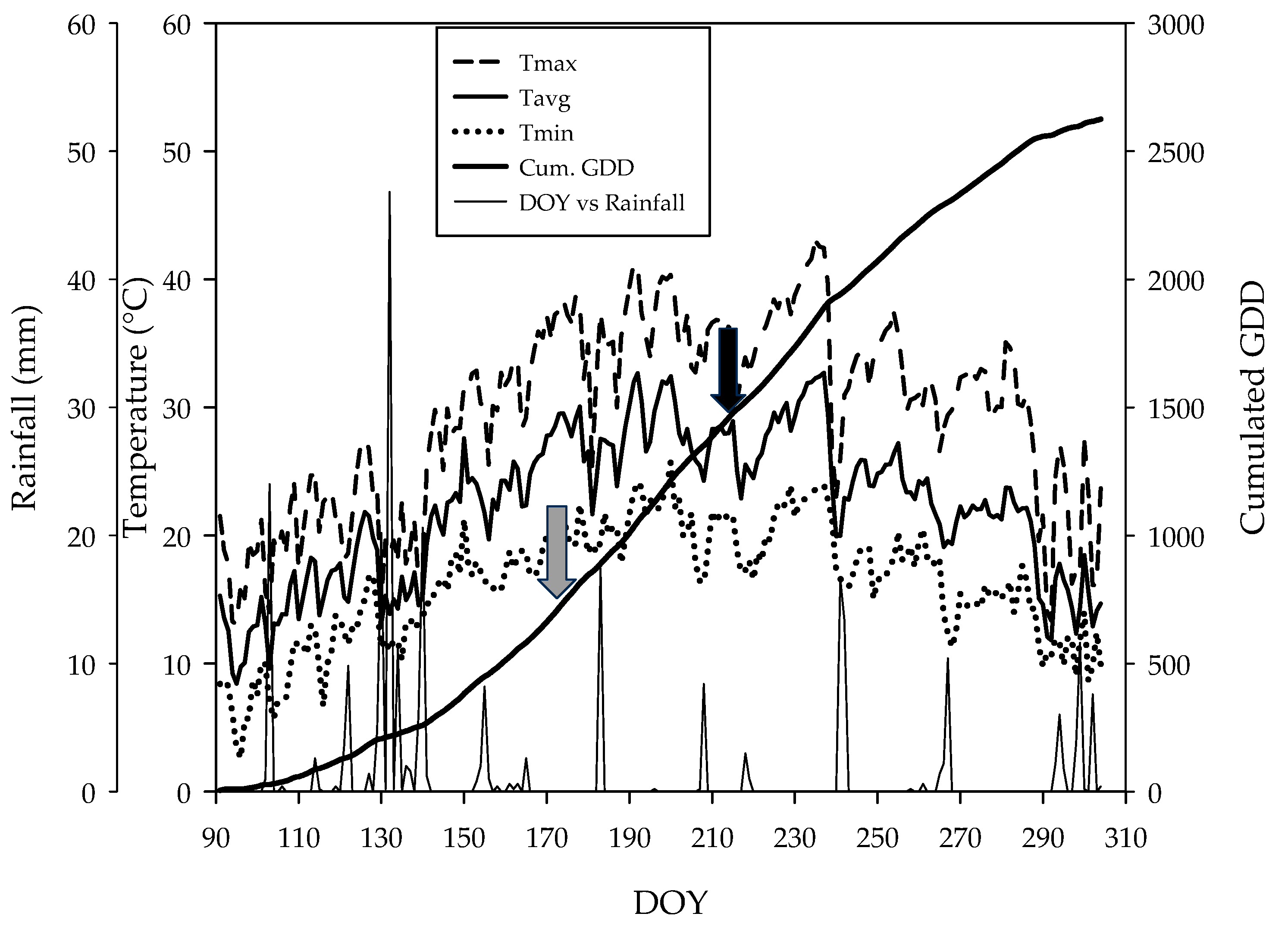

- Well-watered control vines (WW-C): These vines received full irrigation, equating to 100% of the daily evapotranspiration (ET), which averaged 5 L per vine per day, from DOY 171 to DOY 214.

- Moderate irrigation reduction control vines (WS1-C): These vines were irrigated daily at 80% ET, averaging 4 L per vine per day, from DOY 171 to DOY 214.

- Moderate irrigation reduction treated vines (WS1-T): These vines also received daily irrigation at 80% ET, averaging 4 L per vine per day, from DOY 171 to DOY 214, and were subjected to multiple foliar applications of a proline-rich SYD.

- Severe irrigation reduction treated vines (WS2-T): These vines were irrigated daily at 40% ET, averaging 2 L per vine per day, from DOY 171 to DOY 214, and were subjected to multiple foliar applications of a proline-rich SYD.

2.2. Leaf Gas Exchange Parameters and Vine Vegetative Growth

2.3. Leaf Metabolites

2.4. Yield, Vine Balance, and Fruit Composition

2.5. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Weather Conditions

3.2. Soil Moisture and Leaf Water Status

3.3. Leaf Gas Exchanges and Photosystem Efficiency

3.4. Leaf Metabolites

3.5. Yield and Fruit Composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SYD | Specific yeast derivative |

| WW | Well-watered vines |

| WS1 | Vines maintained at 80% ET irrigation |

| WS2 | Vines maintained at 40% ET irrigation |

| C | Untreated control |

| T | Vines subjected to SYD foliar application |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| DOY | Day of Year |

| GDD | Growing degree days |

| WUE | Water use efficiency |

| TSS | Total soluble solids |

| TA | Titratable acidity |

References

- Bertamini, M.; Zulini, L.; Muthuchelian, K.; Nedunchezhian, N. Effect of water deficit on photosynthetic and other physiological responses in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Riesling) plants. Photosynthetica 2006, 44, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesa, I.; Mirás-Avalos, J.M.; De Paz, J.M.; Visconti, F.; Sanz, F.; Yeves, A.; Guerra, D.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Soil management in semi-arid vineyards: Combined effects of organic mulching and no-tillage under different water regimes. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 123, 126198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; VanderWeide, J.; Palliotti, A.; Tombesi, S.; Poni, S.; Sabbatini, P. Foliar vs. soil application of Ascophyllum nodosum extracts to improve grapevine water stress tolerance. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 277, 109807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Bonini, P.; Colla, G. Synergistic action of a microbial-based biostimulant and a plant derived-protein hydrolysate enhances lettuce tolerance to alkalinity and salinity. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, E.; Gonçalves, B.; Cortez, I.; Castro, I. The Role of Biostimulants as Alleviators of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Grapevine: A Review. Plants 2022, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, L.J.; Setati, M.E.; Blancquaert, E.H. Towards a Better Understanding of the Potential Benefits of Seaweed Based Biostimulants in Vitis vinifera L. Cultivars. Plants 2022, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Zozzo, F.; Barmpa, D.M.; Canavera, G.; Giordano, L.; Palliotti, A.; Battista, F.; Poni, S.; Frioni, T. Effects of foliar applications of a proline-rich specific yeast derivative on physiological and productive performances of field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L.). Sci. Hortic. 2024, 326, 112759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Sensoy, S.; Boukhriss, M.; Ben Abdullah, F. Exogenous proline effects on photosynthetic performance and antioxidant defense system of young olive tree. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4216–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Rady, M.O.A.; Marey, R.A.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A. Exogenously applied proline enhances growth and productivity of drought stressed onion by improving photosynthetic efficiency, water use efficiency and up-regulating osmoprotectants. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.A.; Banu, M.N.A.; Nakamura, Y.; Shimoishi, Y.; Murata, Y. Proline and glycinebetaine enhance antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification systems and reduce NaCl-induced damage in cultured tobacco cells. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, P.; Sharmila, P.; Pardha Saradhi, P. Proline Alleviates Salt-Stress-Induced Enhancement in Ribulose-1,5-Bisphosphate Oxygenase Activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 279, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo, E.C.G.; Schuster, I.; Pileggi, M.; Scapim, C.A.; Molinari, H.B.C.; Marur, C.J.; Vieira, L.G.E. Stress-induced synthesis of proline confers tolerance to water deficit in transgenic wheat. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehr, P.P.; Hernández-Montes, E.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Keller, M.; Zörb, C. Abscisic acid and proline are not equivalent markers for heat, drought and combined stress in grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 28, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, M.; Demirel, U.; Kahraman, A. Effects of proline on antioxidant system in leaves of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) exposed to oxidative stress by H2O2. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 119, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.L.; Wang, Z.X.; He, Y.F.; Xue, S.; Zhang, S.Q.; Pei, M.S.; Liu, H.N.; Yu, Y.H.; Guo, D.L. Proline synthesis and catabolism-related genes synergistically regulate proline accumulation in response to abiotic stresses in grapevines. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 305, 111373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.H.; Eichorn, K.W.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, E. Growth Stages of the Grapevine: Phenological growth stages of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and descriptions according to the extended BBCH scale. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Romero, P.; Gohil, H.; Smithyman, R.P.; Riley, W.R.; Casassa, L.F.; Harbertson, J.F. Deficit Irrigation Alters Grapevine Growth, Physiology, and Fruit Microclimate. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 67, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskerville, G.L.; Emin, P. Rapid Estimation of Heat Accumulation from Maximum and Minimum Temperatures. Ecology 1969, 50, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troll, W.; Lindsley, J. A photometric method for the determiation of proline. J. Biol. Chem. 1955, 215, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P.; Gibon, Y. Protocol: Extraction and determination of proline. Prometh. Wiki 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Loreto, F.; Velikova, V. Isoprene produced by leaves protects the photosynthetic apparatus against ozone damage, quenches ozone products, and reduces lipid peroxidation of cellular membranes. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deloire, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Rogiers, S. A few words on grapevine leaf water potential. IVES Tech. Rev. Vine Wine 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments: A review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueh, J.S.H.; Bright, S.W.J. Biochemical and genetical analysis of three proline-accumulating barley mutants. Plant Sci. Lett. 1982, 27, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.E.; Savouré, A.; Szabados, L. Proline metabolism as regulatory hub. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campobenedetto, C.; Agliassa, C.; Mannino, G.; Vigliante, I.; Contartese, V.; Secchi, F.; Bertea, C.M. A biostimulant based on seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum and Laminaria digitata) and yeast extracts mitigateswater stress effects on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Agriculture 2021, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, K.; Attia, K.A.; Niedbała, G.; Wojciechowski, T.; Hafez, Y.; Alamery, S.; Alateeq, T.K.; Arafa, S.A. Mitigation of drought damages by exogenous chitosan and yeast extract with modulating the photosynthetic pigments, antioxidant defense system and improving the productivity of garlic plants. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Puthur, J.T. Biostimulant priming in Oryza sativa: A novel approach to reprogram the functional biology under nutrient-deficient soil. Cereal Res. Commun. 2022, 50, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.M.A.; Shanan, N.T.; Reda, F.M. Active yeast extract counteracts the harmful effects of salinity stress on the growth of leucaena plant. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 201, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohari, G.; Panahirad, S.; Sepehri, N.; Akbari, A.; Zahedi, S.M.; Jafari, H.; Dadpour, M.R.; Fotopoulos, V. Enhanced tolerance to salinity stress in grapevine plants through application of carbon quantum dots functionalized by proline. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 42877–42890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysik, J.; Alia; Bhalu, B.; Mohanty, P. Molecular mechanisms of quenching of reactive oxygen species by proline under stress in plants. Curr. Sci. 2002, 82, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- De Miccolis Angelini, R.M.; Rotolo, C.; Gerin, D.; Abate, D.; Pollastro, S.; Faretra, F. Global transcriptome analysis and differentially expressed genes in grapevine after application of the yeast-derived defense inducer cerevisane. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2020–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, Ș.-O.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Tritean, N.; Ghiurea, M.; Capră, L.; Nicolae, C.-A.; Faraon, V.; Neamțu, C.; Oancea, F. Spectroscopic Analyses Highlight Plant Biostimulant Effects of Baker’s Yeast Vinasse and Selenium on Cabbage through Foliar Fertilization. Plants 2023, 12, 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombe, B.G.; McCarthy, M.G. Dynamics of grape berry growth and physiology of ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2000, 6, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, S.E.; Threlfall, R.T.; Howard, L.R. Impact of Inactivated Yeast Foliar Spray on Chambourcin (Vitis Hybrid) Wine Grapes. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, C.; Allegro, G.; Valentini, G.; Pizziolo, A.; Battista, F.; Spinelli, F.; Filippetti, I. Foliar application of specific yeast derivative enhances anthocyanins accumulation and gene expression in Sangiovese cv (Vitis vinifera L.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portu, J.; López, R.; Baroja, E.; Santamaría, P.; Garde-Cerdán, T. Improvement of grape and wine phenolic content by foliar application to grapevine of three different elicitors: Methyl jasmonate, chitosan, and yeast extract. Food Chem. 2016, 201, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šuklje, K.; Antalick, G.; Buica, A.; Coetzee, Z.A.; Brand, J.; Schmidtke, L.M.; Vivier, M.A. Inactive dry yeast application on grapes modify Sauvignon Blanc wine aroma. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; López, R.; Portu, J.; González-Arenzana, L.; López-Alfaro, I.; Santamaría, P. Study of the effects of proline, phenylalanine, and urea foliar application to Tempranillo vineyards on grape amino acid content. Comparison with commercial nitrogen fertilisers. Food Chem. 2014, 163, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Portu, J.; López, R.; Santamaría, P. Effect of Foliar Applications of Proline, Phenylalanine, Urea, and Commercial Nitrogen Fertilizers on Stilbene Concentrations in Tempranillo Musts and Wines. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | DF | Sig. 1 | F | SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 2 | *** | 27 | 385.415 |

| Intercept | 1 | *** | 27 | 837.709 |

| Interaction (treatmentx gs) | 2 | *** | 27 | 385.415 |

| Treatment | Yield (kg/Vine) | Cluster Weight (g) | Berry Weight (g) | Cluster Compactness (g/cm) | Vine Leaf Area (m2) | Leaf Area/ Yield (m2/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WW-C | 1.82 a 1 | 126.07 ab | 1.62 a | 10.99 | 2.58 | 1.44 |

| WS1-C | 1.54 ab | 118.62 ab | 1.40 ab | 9.78 | 2.41 | 1.49 |

| WS1-T | 1.76 a | 134.7 a | 1.59 a | 11.85 | 1.86 | 1.39 |

| WS2-T | 1.37 b | 105 b | 1.21 b | 9.73 | 2.32 | 1.51 |

| Sig. | ** 2 | * | ** | ns | ns | ns |

| Treatment | TSS (Brix) | pH | TA (g/L) | TSS/TA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WW-C | 19.00 b 1 | 3.15 | 7.77 a | 2.45 b |

| WS1-C | 19.89 ab | 3.18 | 6.15 b | 3.23 ab |

| WS1-T | 20.89 ab | 3.19 | 6.62 ab | 3.16 ab |

| WS2-T | 21.06 a | 3.18 | 6.15 b | 3.42 a |

| Sig. | ** 2 | ns | ns | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tiwari, H.; Bonicelli, P.G.; Ripa, C.; Poni, S.; Battista, F.; Frioni, T. Proline-Rich Specific Yeast Derivatives Enhance Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Water Status and Enable Reduced Irrigation Volumes. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122759

Tiwari H, Bonicelli PG, Ripa C, Poni S, Battista F, Frioni T. Proline-Rich Specific Yeast Derivatives Enhance Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Water Status and Enable Reduced Irrigation Volumes. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122759

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiwari, Harsh, Pier Giorgio Bonicelli, Clara Ripa, Stefano Poni, Fabrizio Battista, and Tommaso Frioni. 2025. "Proline-Rich Specific Yeast Derivatives Enhance Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Water Status and Enable Reduced Irrigation Volumes" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122759

APA StyleTiwari, H., Bonicelli, P. G., Ripa, C., Poni, S., Battista, F., & Frioni, T. (2025). Proline-Rich Specific Yeast Derivatives Enhance Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Water Status and Enable Reduced Irrigation Volumes. Agronomy, 15(12), 2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122759