Comparative Multi-Omics Insights into Flowering-Associated Sucrose Accumulation in Contrasting Sugarcane Cultivars

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

2.2. Sugar Content Measurement

2.3. RNA Sequencing and Transcriptomic Analysis

2.4. Metabolite Extraction and Metabolomic Profiling

2.5. Time Series Trend Analysis

2.6. Integrated Transcriptome–Metabolome Analysis

3. Results

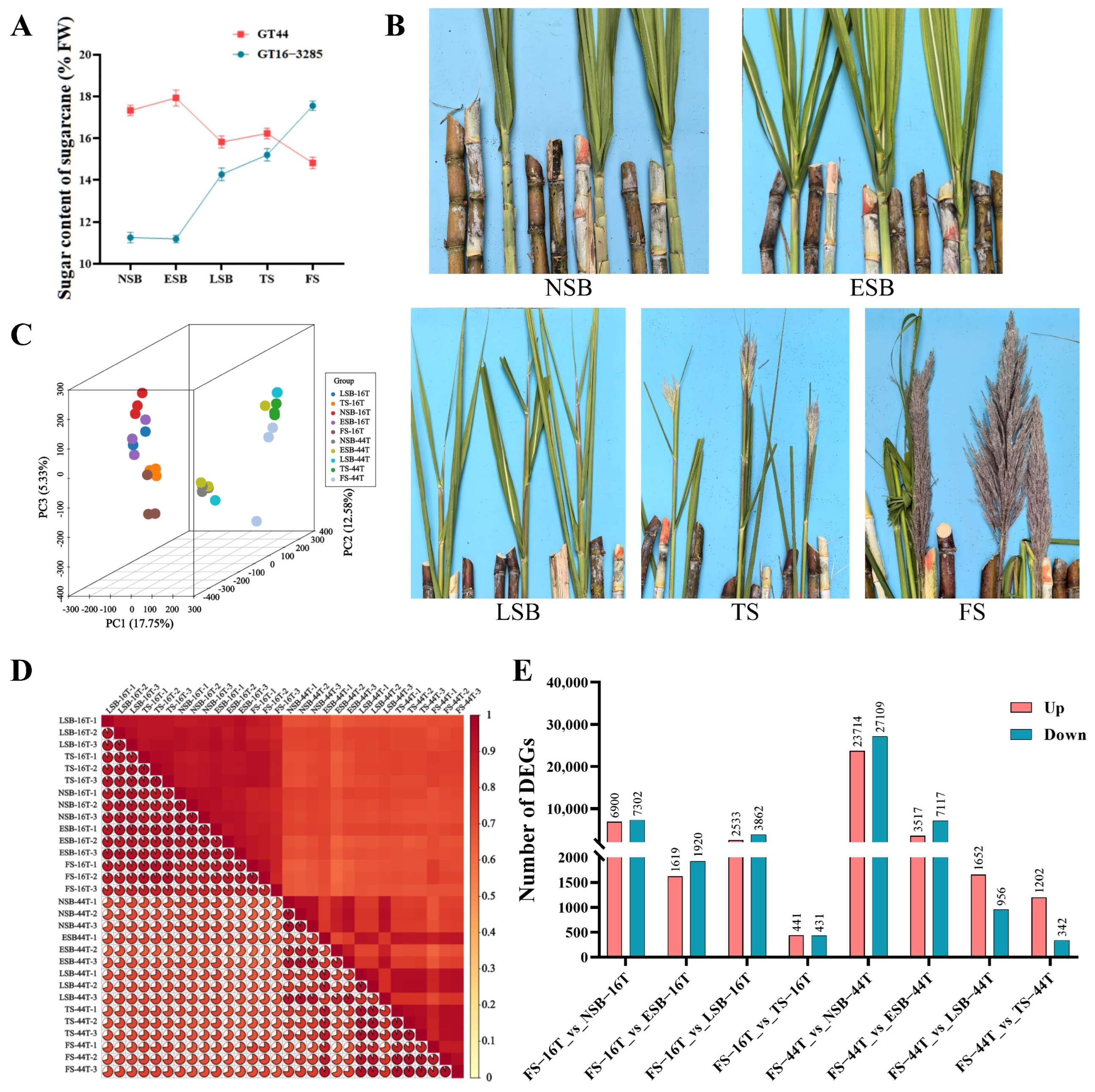

3.1. Sugar Content Dynamics and Transcriptome Sample Quality During Sugarcane Flowering

3.2. Comparative Functional Enrichment and Expression Dynamics of DEGs in GT16 and GT44 During Flowering

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Co-Expressed and Differentially Regulated Genes Between GT16 and GT44 During Flowering

3.4. Metabolomic Dynamics in GT16 and GT44 During Flowering

3.5. Integrated Transcriptome–Metabolome Analysis Reveals Cultivar-Specific Carbon Partitioning During Flowering

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultivar-Specific Carbon Partitioning During Flowering Underlies Opposite Sugar Trajectories

4.2. Practical Measures During Flowering to Raise Sugar

4.3. Limitations and Comparison with Existing Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehdi, F.; Galani, S.; Wickramasinghe, K.P.; Zhao, P.; Lu, X.; Lin, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Current perspectives on the regulatory mechanisms of sucrose accumulation in sugarcane. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohwer, J.M.; Botha, F.C. Analysis of sucrose accumulation in the sugar cane culm on the basis of in vitro kinetic data. Biochem. J. 2001, 358 Pt 2, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uys, L.; Botha, F.C.; Hofmeyr, J.-H.S.; Rohwer, J.M. Kinetic model of sucrose accumulation in maturing sugarcane culm tissue. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2375–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavani, G.; Malhotra, P.K.; Verma, S.K. Flowering in sugarcane-insights from the grasses. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh Babu, K.S.; Janakiraman, V.; Palaniswamy, H.; Kasirajan, L.; Gomathi, R.; Ramkumar, T.R. A short review on sugarcane: Its domestication, molecular manipulations and future perspectives. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022, 69, 2623–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, L.; da Cruz, S.J.S.; Vilela, R.D.; dos Santos, J.M.; Barbosa, G.V.D.S.; Silva, J.A.C. Foliar Applications of Calcium Reduce and Delay Sugarcane Flowering. BioEnergy Res. 2016, 9, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berding, N.; Hurney, A.P. Flowering and lodging, physiological-based traits affecting cane and sugar yield: What do we know of their control mechanisms and how do we manage them? Field Crops Res. 2005, 92, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, F.; Liu, X.; Riaz, Z.; Javed, U.; Aman, A.; Galani, S. Expression of sucrose metabolizing enzymes in different sugarcane varieties under progressive heat stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1269521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manechini, J.R.V.; Santos, P.H.d.S.; Romanel, E.; Brito, M.D.S.; Scarpari, M.S.; Jackson, S.; Pinto, L.R.; Vicentini, R. Transcriptomic Analysis of Changes in Gene Expression During Flowering Induction in Sugarcane Under Controlled Photoperiodic Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 635784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdi, F.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gan, Y.; Cai, W.; Peng, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, B. Factors affecting the production of sugarcane yield and sucrose accumulation: Suggested potential biological solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1374228. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, O.; Granot, D. An Overview of Sucrose Synthases in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, I.; Roopendra, K.; Sharma, A.; Chandra, A.; Kamal, A. Expression analysis of genes associated with sucrose accumulation and its effect on source-sink relationship in high sucrose accumulating early maturing sugarcane variety. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2019, 25, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.K.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Verma, P.C.; Solomon, S.; Singh, S.B. Functional analysis of sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) and sucrose synthase (SS) in sugarcane (Saccharum) cultivars. Plant Biol. 2011, 13, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, J.S.; Chen, L.Q.; Sosso, D.; Julius, B.T.; Lin, I.W.; Qu, X.Q.; Braun, D.M.; Frommer, W.B. SWEETs, transporters for intracellular and intercellular sugar translocation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.M.; Wang, L.; Ruan, Y.L. Understanding and manipulating sucrose phloem loading, unloading, metabolism, and signalling to enhance crop yield and food security. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1713–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, A.-M.; Liao, F.; Qin, C.-X.; Chen, Z.-L.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.-R.; Li, X.-F.; Lakshmanan, P.; Huang, D.-L. Control of sucrose accumulation in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrids) involves miRNA-mediated regulation of genes and transcription factors associated with sugar metabolism. GCB Bioenergy 2022, 14, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zang, L.; Jiao, F.; Perez-Garcia, M.-D.; Ogé, L.; Hamama, L.; Le Gourrierec, J.; Sakr, S.; Chen, J. Sugar Signaling and Post-transcriptional Regulation in Plants: An Overlooked or an Emerging Topic? Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 578096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Qin, C.; Wang, M.; Liao, F.; Liao, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Lakshmanan, P.; Long, M.; Huang, D. Ethylene-mediated improvement in sucrose accumulation in ripening sugarcane involves increased sink strength. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, G.; Islam, M.R.; Fu, W.; Feng, B.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Abscisic acid synergizes with sucrose to enhance grain yield and quality of rice by improving the source-sink relationship. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Q.; Qin, Y.; Guo, D.-J.; Chen, J.-Y.; Zeng, X.-P.; Mahmood, A.; Yang, L.-T.; Liang, Q.; Song, X.-P.; Xing, Y.-X.; et al. Sucrose metabolism analysis in a high sucrose sugarcane mutant clone at a mature stage in contrast to low sucrose parental clone through the transcriptomic approach. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y.; Liang, G.; Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Xi, R. Sugar Metabolism and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal Key Sugar Transporters during Camellia oleifera Fruit Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirugnanasambandam, P.P.; Mason, P.J.; Hoang, N.V.; Furtado, A.; Botha, F.C.; Henry, R.J. Analysis of the diversity and tissue specificity of sucrose synthase genes in the long read transcriptome of sugarcane. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.J.; Hoang, N.V.; Botha, F.C.; Furtado, A.; Marquardt, A.; Henry, R.J. Comparison of the root, leaf and internode transcriptomes in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrids). Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Shen, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Akbar, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Functional characterization and analysis of transcriptional regulation of sugar transporter SWEET13c in sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassop, D.; Rae, A.L. Expression of sugarcane genes associated with perception of photoperiod and floral induction reveals cycling over a 24-hour period. Funct. Plant Biol. 2019, 46, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venail, J.; da Silva Santos, P.H.; Manechini, J.R.; Alves, L.C.; Scarpari, M.; Falcão, T.; Romanel, E.; Brito, M.; Vicentini, R.; Pinto, L.; et al. Analysis of the PEBP gene family and identification of a novel FLOWERING LOCUS T orthologue in sugarcane. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, D.A.; Martins, M.C.M.; Cheavegatti-Gianotto, A.; Carneiro, M.S.; Amadeu, R.R.; Aricetti, J.A.; Wolf, L.D.; Hoffmann, H.P.; de Abreu, L.G.F.; Caldana, C. Metabolite Profiles of Sugarcane Culm Reveal the Relationship Among Metabolism and Axillary Bud Outgrowth in Genetically Related Sugarcane Commercial Cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijma, M.; Lembke, C.G.; Diniz, A.L.; Santini, L.; Zambotti-Villela, L.; Colepicolo, P.; Carneiro, M.S.; Souza, G.M. Planting Season Impacts Sugarcane Stem Development, Secondary Metabolite Levels, and Natural Antisense Transcription. Cells 2021, 10, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Dong, F.; Pang, Z.; Fallah, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, C. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptome Analyses Unveil Pathways Involved in Sugar Content and Rind Color of Two Sugarcane Varieties. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 921536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Bai, X.; Wu, Z.; Ren, S.; Xie, H.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tian, D.; Song, S. SugarcaneOmics: An integrative multi-omics platform for sugarcane research. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlo, V.; Margarido, G.R.A.; Botha, F.C.; Furtado, A.; Hodgson-Kratky, K.; Correr, F.H.; Henry, R.J. Transcriptome changes in the developing sugarcane culm associated with high yield and early-season high sugar content. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 1619–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlo, V.; Furtado, A.; Botha, F.C.; Margarido, G.R.A.; Hodgson-Kratky, K.; Choudhary, H.; Gladden, J.; Simmons, B.; Henry, R.J. Transcriptome and metabolome integration in sugarcane through culm development. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.; Mueller, O.; Stocker, S.; Salowsky, R.; Leiber, M.; Gassmann, M.; Lightfoot, S.; Menzel, W.; Granzow, M.; Ragg, T. The RIN: An RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, N.J.; von Schaewen, A. The oxidative pentose phosphate pathway: Structure and organisation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.; Lawson, T.; Zakhleniuk, O.V.; Lloyd, J.C.; Raines, C.A.; Fryer, M. Increased sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase activity in transgenic tobacco plants stimulates photosynthesis and growth from an early stage in development. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, D.M.; Locke, A.M.; Khozaei, M.; Raines, C.A.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Over-expressing the C3 photosynthesis cycle enzyme Sedoheptulose-1-7 Bisphosphatase improves photosynthetic carbon gain and yield under fully open air CO2 fumigation (FACE). BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Ai, X. Changes in SBPase activity influence photosynthetic capacity, growth, and tolerance to chilling stress in transgenic tomato plants. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J.; Komor, E.; Moore, P.H. Sucrose Accumulation in the Sugarcane Stem Is Regulated by the Difference between the Activities of Soluble Acid Invertase and Sucrose Phosphate Synthase. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholme, R.; De Meester, B.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis and its integration into metabolism. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunn, J.E.; Delorge, I.; Figueroa, C.M.; van Dijck, P.; Stitt, M. Trehalose metabolism in plants. Plant J. 2014, 79, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.P.; Minow, M.A.A.; Chalfun-Júnior, A.; Colasanti, J. Putative sugarcane FT/TFL1 genes delay flowering time and alter reproductive architecture in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, A.L.; Grof, C.P.L.; Casu, R.E.; Bonnett, G.D. Sucrose accumulation in the sugarcane stem: Pathways and control points for transport and compartmentation. Field Crops Res. 2005, 92, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassop, D.; Roessner, U.; Bacic, A.; Bonnett, G.D. Changes in the sugarcane metabolome with stem development. Are they related to sucrose accumulation? Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanholme, R.; Demedts, B.; Morreel, K.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin Biosynthesis and Structure. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.; Roopendra, K.; Verma, I. Transcriptome analysis of the effect of GA3 in sugarcane culm. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, W.; Zhu, F.; Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Ming, R.; Zhang, J. Structure, phylogeny, allelic haplotypes and expression of sucrose transporter gene families in Saccharum. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini-Terzi, F.S.; Rocha, F.R.; Vêncio, R.Z.N.; Felix, J.M.; Branco, D.S.; Waclawovsky, A.J.; Del Bem, L.E.V.; Lembke, C.G.; Costa, M.D.L.; Nishiyama, M.Y.; et al. Sugarcane genes associated with sucrose content. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Hua, X.; Ma, X.; Zhu, F.; Jones, T.; Zhu, X.; Bowers, J.; et al. Allele-defined genome of the autopolyploid sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum L. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Q.; Chen, J.-Y.; Zeng, X.-P.; Qin, Y.; Guo, D.-J.; Mahmood, A.; Yang, L.-T.; Liang, Q.; Song, X.-P.; Xing, Y.-X.; et al. Transcriptomic exploration of a high sucrose mutant in comparison with the low sucrose mother genotype in sugarcane during sugar accumulating stage. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1448–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis Chemical Analysis Working Group (CAWG) Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI). Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene ID | Gene Annotation | NSB-16T | ESB-16T | LSB-16T | TS-16T | FS-16T | NSB-44T | ESB-44T | LSB-44T | TS-44T | FS-44T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sh_So07J0291059 | -- | 2.61 | 3.75 | 5.51 | 6.93 | 6 | 15.43 | 16.92 | 12.34 | 6.3 | 3.9 |

| Sh_Ss03I0175557 | -- | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.16 | 1.86 | 2.27 | 0.82 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Sh_Ss06A0234469 | FOG: RRM domain | 1.28 | 1.83 | 1.49 | 2.54 | 2.59 | 1.12 | 1.03 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Sh_Ss02J0139920 | Serine protease | 0.56 | 0.7 | 0.92 | 1.05 | 1.61 | 10.84 | 12.94 | 6.42 | 3.78 | 2.15 |

| Sh_So03C0150236 | -- | 2.42 | 2.63 | 3.85 | 3.66 | 5.11 | 7.81 | 6.32 | 5.09 | 3.65 | 2.67 |

| Sh_Ss04H0210996 | Fumarylacetoacetase | 8.56 | 7.69 | 16.71 | 14.51 | 18.87 | 1.7 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Sh_So06G0249797 | Predicted Yippee-type zinc-binding protein | 2.8 | 4.58 | 5.61 | 6.77 | 9.78 | 0.9 | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.09 |

| Sh_Ss02H0127675 | Acyl-CoA reductase | 0.23 | 0.56 | 0.4 | 0.92 | 1.77 | 3.73 | 3.02 | 1 | 0.76 | 0.87 |

| Sh_Ss02I0131514 | Succinate dehydrogenase | 2.81 | 3.63 | 4.96 | 6.45 | 6.88 | 2.07 | 1.44 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Sh_Ss01G0068962 | Mitochondrial processing peptidase | 4.56 | 6.09 | 6.3 | 10.88 | 10.16 | 6.44 | 3.07 | 2.76 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| Sh_So01C0044634 | Branched chain aminotransferase BCAT1 | 3.52 | 2.69 | 3.89 | 8.89 | 8.91 | 6 | 4.66 | 3.11 | 0.59 | 0.34 |

| Sh_Ss10F0013919 | -- | 4.52 | 8.18 | 5.37 | 14.77 | 12.05 | 12.54 | 11.56 | 6.83 | 2.91 | 1.91 |

| novel.10541 | -- | 4.16 | 1.54 | 0.68 | 2.02 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.73 | 1.81 | 6.5 | 4.34 |

| Sh_So10J0024098 | -- | 7.19 | 3.94 | 2.38 | 2.15 | 1.69 | 1.51 | 1.43 | 2.23 | 4.34 | 4.15 |

| Sh_So01B0036338 | -- | 1.11 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.63 |

| Sh_So01H0074036 | -- | 13.39 | 8.72 | 7.9 | 7.03 | 4.87 | 6.51 | 6 | 13.43 | 20.75 | 14.11 |

| Sh_So01H0071334 | Conserved protein, contains TBC domain | 3.29 | 1.38 | 0.92 | 1.92 | 1.15 | 0.11 | 0.23 | 1.95 | 1.69 | 1.36 |

| Sh_Ss03F0161019 | -- | 3.49 | 1.45 | 1.39 | 1.22 | 1.14 | 1.68 | 1.34 | 2.24 | 2.73 | 3.89 |

| novel.11560 | -- | 9.01 | 4.31 | 4.49 | 4.01 | 2.67 | 4.76 | 2.3 | 5.36 | 9.74 | 8.92 |

| Sh_Ss03B0147646 | Glutathione S-transferase | 36.59 | 8.47 | 12.49 | 2.95 | 1.84 | 3.96 | 3.21 | 14.58 | 11.53 | 12.64 |

| Sh_Ss04H0212092 | -- | 7.91 | 9.54 | 4.78 | 4.66 | 2.78 | 0.17 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 1.59 | 1.45 |

| Sh_So03C0151558 | Calcyclin-binding protein CacyBP | 5.04 | 1.6 | 1.28 | 1.87 | 1.29 | 3.96 | 4.84 | 8.24 | 6.97 | 7.81 |

| Sh_Ss03B0147107 | Aspartyl protease | 0.91 | 0.46 | 0.2 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.9 | 0.67 | 1.38 |

| Sh_Ss04H0213186 | Aspartyl protease | 13.58 | 6.03 | 6.35 | 7.72 | 4.16 | 6.27 | 8 | 7.38 | 14.61 | 13.43 |

| Sh_Ss02H0129712 | Predicted spermine/spermidine synthase | 6.43 | 3.47 | 3.08 | 1.38 | 1.21 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 1.1 | 2.24 | 1.84 |

| Sh_Ss04E0202415 | -- | 13.95 | 13.99 | 7.2 | 4.74 | 4.35 | 2.11 | 3.04 | 4.39 | 4.35 | 5.83 |

| Sh_So01K0090514 | Deoxyribodipyrimidine | 5.16 | 4.28 | 2.48 | 0.4 | 5.93 | 2.03 | 0.58 | 2.46 | 5.46 | 11.66 |

| Sh_Ss10I0022398 | -- | 4.04 | 2.86 | 1.48 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.95 |

| novel.16372 | -- | 4.43 | 2 | 2.29 | 1.92 | 1.07 | 1.94 | 1.17 | 2.46 | 4.54 | 3.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Fang, W.; Yan, J.; Yan, H.; Lei, J.; Qiu, L.; Srithawong, S.; Li, D.; Luo, T.; Zhou, H.; et al. Comparative Multi-Omics Insights into Flowering-Associated Sucrose Accumulation in Contrasting Sugarcane Cultivars. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122747

Li M, Fang W, Yan J, Yan H, Lei J, Qiu L, Srithawong S, Li D, Luo T, Zhou H, et al. Comparative Multi-Omics Insights into Flowering-Associated Sucrose Accumulation in Contrasting Sugarcane Cultivars. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122747

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ming, Weikuan Fang, Jing Yan, Haifeng Yan, Jingchao Lei, Lihang Qiu, Suparat Srithawong, Du Li, Ting Luo, Huiwen Zhou, and et al. 2025. "Comparative Multi-Omics Insights into Flowering-Associated Sucrose Accumulation in Contrasting Sugarcane Cultivars" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122747

APA StyleLi, M., Fang, W., Yan, J., Yan, H., Lei, J., Qiu, L., Srithawong, S., Li, D., Luo, T., Zhou, H., Tang, S., Zhou, H., He, S., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Comparative Multi-Omics Insights into Flowering-Associated Sucrose Accumulation in Contrasting Sugarcane Cultivars. Agronomy, 15(12), 2747. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122747