Abstract

(1) Objective: To investigate the chemical defense response mechanisms of two cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L., Malvaceae) varieties, Xinlu Zhong 57 and Xinlu Zhong 78, in response to feeding by the cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii Glover, 1877) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in the Kashi region. (2) Methods: The artificial infestation method was adopted to determine the dynamic changes in the contents of secondary metabolites (tannins, total phenols), activities of protective enzymes (SOD, POD, PPO), and contents of nutrients (soluble sugars, amino acids) in cotton leaves at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after infestation with cotton aphids. (3) Results: The contents of secondary metabolites and the activities of protective enzymes in both varieties showed an initial increase followed by a decrease. The response of Xinlu Zhong 57 was earlier and stronger. Its tannin and total phenol contents reached a peak at 48 h, with values of 264.2 nmol/g and 5.973 mg/g, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of Xinlu Zhong 78 (p < 0.05). The activities of SOD, POD, and PPO were consistently higher in Xinlu Zhong 57. At 48 h post-inoculation, SOD activity in Xinlu Zhong 57 was 238.1 U/g, significantly higher than in Xinlu Zhong 78 (p < 0.05). POD activity was 49.0 U/g, and PPO activity was 94.5 U/g, both significantly higher than those of Xinlu Zhong 78 (p < 0.05). This suggests that Xinlu Zhong 57 has a stronger ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species. Regarding nutrients, soluble sugar content in Xinlu Zhong 57 was 6.99 mg/g at 96 h, significantly higher than that in Xinlu Zhong 78 (p < 0.05). The amino acid content at 96 h was 224.4 μg/g, also significantly higher than in Xinlu Zhong 78 (p < 0.05). (4) Conclusions: Xinlu Zhong 57 forms a more effective chemical defense system by rapidly activating the defense enzyme system, efficiently accumulating secondary metabolites, and optimizing nutrient allocation. This study provides a theoretical basis for elucidating the physiological mechanisms of cotton resistance induced by cotton aphids by analyzing the effects of cotton aphid stress on the contents of secondary metabolites, protective enzyme activities, and nutrient contents in cotton leaves.

1. Introduction

Cotton is the most important natural fiber crop in China and worldwide [1]. It underpins global fiber production and trade, playing a significant role in the world fiber market [2]. Xinjiang, with its unique natural environment, efficient mechanized production system, and the development opportunities provided by the Belt and Road Initiative, holds a dominant position in China’s cotton industry: For 25 consecutive years, it has led the nation in total production, yield, and planting area, contributing significantly to the national cotton output [3]. The cotton aphid is one of the major pests of cotton in Xinjiang, posing a serious threat to production. Currently, chemical control remains one of the primary measures to manage cotton aphid damage. However, excessive pesticide use has led to increasing resistance in cotton aphids [4]. Moreover, the unsustainable nature of chemical pesticides and their harmful effects on non-target organisms and human health have become a growing concern [5]. Given these issues, there is an urgent need to explore effective and sustainable alternatives. With growing emphasis on green agriculture and sustainable development, breeding and utilizing aphid-resistant cotton varieties has become an important strategy for cotton aphid management [6]. Elucidating cotton’s aphid resistance mechanisms is fundamental for screening resistant varieties and provides far-reaching implications for future breeding at the physiological, biochemical, and molecular levels. Previous studies [7,8,9] have demonstrated that resistant cotton and related host plants not only possess higher activities of defense-related enzymes and accumulate greater levels of phenolic compounds but also experience markedly reduced cotton aphid damage. For example, resistant varieties showed 35–60% lower cotton aphid populations and exhibited delayed leaf curling or chlorosis by 48–72 h under comparable infestation densities (10–15 cotton aphids per leaf).

Studies have shown that plants can enhance their resistance under pest stress by adjusting secondary metabolite levels (such as tannins and total phenols) and activating antioxidant defense enzyme systems like superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) [10,11,12]. Previous work supports this: for example, Yu et al. [13] found that tannin and total phenol contents in an aphid-resistant goji berry variety were significantly higher than in susceptible varieties. Chen et al. [10] demonstrated that cotton aphid feeding can significantly induce PPO and POD activities in cotton, with a stronger response in resistant varieties. In addition, changes in nutrients such as soluble sugars and amino acids are closely related to insect resistance [14]. Cotton aphid feeding can significantly alter soluble sugar levels in cotton under different infestation densities and durations [11], and soluble sugar content is positively correlated with cotton aphid resistance [15].

However, most previous studies focused on single indicators or short-term responses, lacking a systematic comparison of the physiological and biochemical dynamics of different cotton varieties under continuous cotton aphid feeding stress. In particular, the chemical defense characteristics of the main cultivated cotton varieties in the Kashi region under cotton aphid stress have not been clearly elucidated. Therefore, this study explored the differences and dynamic changes in leaf secondary metabolite contents (tannins and total phenols), protective enzyme activities (SOD, PPO, POD), and nutrient levels (soluble sugars and amino acids) in different cotton varieties under cotton aphid feeding stress. By measuring these parameters in multiple cotton varieties under cotton aphid stress, we aimed to clarify cotton’s resistance mechanisms from chemical and physiological perspectives. The findings are expected to provide a theoretical reference for aphid-resistant cotton breeding in southern Xinjiang and for further studies on induced cotton aphid resistance mechanisms in cotton.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Tested cotton: The two cotton varieties with the greatest difference in cotton aphid resistance (Xinlu Zhong 57 and Xinlu Zhong 78) were selected based on the cotton aphid ratio. They were sown on 19 April 2025, in the experimental field of the School of Modern Agriculture at Kashi University (39°29′29″ N, 76°5′1″ E). The planting pattern was “one film for four rows” with a plant spacing of 10 cm and a row spacing of (66 + 10) cm. The film width was 2.26 m. Field management practices were consistent, and the average plant height was approximately 55 cm. During the growth period, irrigation, fertilization, and weed control were conducted according to local standard operating procedures. No pesticides were applied, and no other major pests were observed during the experimental period.

Tested cotton aphids: The cotton aphids were collected from Awati Township, Kashi City (39°29′13″ N, 76°8′42″ E) and reared in an RXZ-500D intelligent climate chamber (Shanghai Kuncheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at the Insect Laboratory of the School of Modern Agriculture, Kashi University. The chamber was maintained at 26 ± 1 °C, with 70 ± 10% relative humidity and a 14 h light/10 h dark photoperiod.

Reagents and instruments: Tannic acid standard (Shanghai Yezhi Detection Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); tannin content detection kit (Shanghai Yezhi Detection Technology Co., Ltd.); gallic acid standard solution (Beijing Box Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); total phenol content detection kit (Beijing Box Biotech Co., Ltd.); peroxidase activity detection kit (Beijing Lanjieke Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); polyphenol oxidase activity detection kit (Beijing Box Biotech Co., Ltd.); superoxide dismutase activity detection kit (Beijing Leigen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); soluble sugar content detection kit (Beijing Box Biotech Co., Ltd.); amino acid detection kit (Beijing Leigen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.); constant temperature water bath (Changzhou Jintan Liangyou Instrument Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China); high-speed refrigerated centrifuge (Hunan Hengnuo Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., Changsha, China); ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Shanghai Lengguang Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); electrically heated blast drying oven (Changzhou Jintan Liangyou Instrument Co., Ltd.); ultrasonic cleaner (Kunshan Ultrasonic Instrument Co., Ltd., Kunshan, China).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Experimental Design

On 15 June 2025, cotton aphids were artificially inoculated onto the cotton plants to simulate field infestation levels. The experimental treatments were set up based on the cotton varieties to simulate real-world infestation conditions. For the two cotton varieties, Xinlu Zhong 57 and Xinlu Zhong 78, ten 1st to 2nd instar nymphs were placed on each plant, evenly distributed across the true leaves to allow feeding. Vaseline was applied under the cotyledons to prevent the cotton aphids from escaping [10]. There were two treatments in total (one for each variety), with three replicates per treatment, and each replicate consisted of 30 cotton plants. During the experiment, cotton aphid infestation was monitored in a timely manner. Any occurrence of other pests was promptly removed to ensure that no other pest affected the cotton plants during the trial. Control group plants were kept free from any pest damage. Sampling was conducted at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 96 h after inoculation. For each sampling time, 10 leaves were randomly collected from each replicate (three replicates per treatment). The collected leaf samples were processed differently according to the different analysis items. Some samples were wrapped in aluminum foil, labeled, and stored in a −80 °C freezer for later use in the determination of protective enzyme activities (SOD, PPO, POD) and nutrients (soluble sugar and amino acids). The other part was placed in a triangular bag, dried in an electrically heated blast drying oven at 60 °C until constant weight, ground with a mortar, passed through a 40-mesh sieve, and then stored in a plastic-sealed bag for later use in the determination of secondary metabolites (tannins and total phenols).

2.2.2. Determination of Secondary Metabolite Content in Cotton Leaves

Determination of Tannin Content: The method for measuring tannin content was based on that of Wang et al. [16] with slight modifications. A 10 mg of tannic acid standard was weighed and sequentially diluted with extraction solution to prepare a series of standard solutions with concentrations of 6.25, 3.125, 1.5625, 0.78625, 0.4, and 0.2 nmol/mL. The absorbance of each standard solution was measured at 275 nm, using the blank extraction solution as zero reference. A standard curve was plotted with the standard solution concentration on the x-axis and ΔA on the y-axis to obtain the equation y = kx + b. Cotton leaves were dried to constant weight and ground through a 40-mesh sieve; approximately 0.1 g of powder was weighed and added to 2 mL of extraction solution. The mixture was extracted in a 70 °C water bath for 30 min with occasional shaking. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm (25 °C, 10 min), the supernatant was collected and brought to 2 mL with extraction solution. The reagents and procedures from the tannin content detection kit were followed for control and sample tubes. Samples were thoroughly mixed and shaken for 5 min, then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min. The absorbance of the sample and control at 275 nm was recorded (,). The sample concentration x (nmol/mL) was then calculated by substituting the value into the standard curve Equation:

where x is the sample concentration obtained from the standard curve (nmol/mL), W is the sample mass, 0.1 g; Vextraction is the volume of the extraction solution, 2 mL.

Determination of Total Phenol Content: The method for measuring total phenol content was based on that of Cao et al. [17] with slight modifications. A 5 mg/mL gallic acid standard solution was diluted with distilled water to prepare standard dilutions of 0.2, 0.15, 0.1, 0.05, 0.025, and 0.0125 mg/mL. A standard curve was plotted with the standard dilution concentration on the x-axis and the corresponding ΔA standard on the y-axis to obtain the standard equation y = kx + b. The sample concentration x(mg/mL) was calculated by substituting into the equation. The surface dirt of cotton leaves was wiped clean, and the leaves were dried to constant weight, crushed, and passed through a 30–50 mesh sieve. Dried and crushed sample (0.1 g) was weighed, and 2 mL of extraction solution was added. Ultrasonic extraction was performed using an ultrasonic cleaner at a power of 300 W and a temperature of 60 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at room temperature for 10 min, the supernatant was collected as the sample to be tested. The reagents and procedures provided in the total phenol content detection kit were followed for the control and experimental samples. The samples were thoroughly mixed and kept at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance of each tube was measured at a wavelength of 760 nm using a 1 mL cuvette with distilled water as the blank:

where x is the concentration of the sample extract obtained from the standard curve (mg·mL−1); W is the sample mass (0.1 g); Vextraction is the volume of the extraction solution (2 mL).

2.2.3. Determination of Enzyme Activity in Cotton Leaves

Determination of POD Activity: The method for measuring peroxidase activity was based on Li [18] and Wang et al. [19] with slight modifications. Leaf samples collected from the field and stored at −80 °C were thawed before use. The samples were rinsed to remove surface dust, cut into small pieces, and homogenized thoroughly. Approximately 0.1 g of tissue was weighed, and 1 mL of extraction buffer was added. The mixture was ground in an ice bath, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and kept on ice for testing. The reagents and procedures supplied with the POD activity detection kit were followed. Distilled water was used to zero the spectrophotometer at 470 nm. The absorbance was recorded immediately as A1 and again after 1 min as A2:

where W is the sample mass (0.1 g); V is the volume of extraction solution (1 mL); V1 is the volume of sample added (0.04 mL); T is the reaction time (1 min); and ΔA = A2 − A1.

Determination of PPO Activity: The method for measuring PPO activity was based on that of Ren et al. [20] with slight modifications. For the enzyme activity assays, the fresh leaf samples that had been stored at −80 °C were used. Fresh cotton leaves were cleaned to remove surface dirt, cut into small pieces, mixed well, and 0.1 g of the tissue was weighed. A total of 1 mL of extraction solution was added, and the mixture was shaken in an ice bath. After centrifugation at 8000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and kept on ice for further testing. The reagents and procedures provided in the polyphenol oxidase activity detection kit were followed for the control and test samples. After thorough mixing, the reaction was carried out accurately at 25 °C for 10 min, followed by immediate treatment at 90 °C for 10 min. The mixture was sealed to prevent water loss. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 1000 rpm at room temperature for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a 1 mL glass cuvette, and the absorbance at 410 nm was measured for each tube ( = Atest − Acontrol):

where Vreaction is the total reaction volume (0.9 mL); W is the sample mass (0.10 g); and T is the reaction time (10 min).

Determination of SOD Activity: The method for measuring SOD activity was based on that of Zhang et al. [21]. For the enzyme activity assays, the fresh leaf samples that had been stored at −80 °C were used. Fresh cotton leaves were cleaned to remove surface dirt, cut into small pieces, mixed well, and 0.4 g of the tissue was weighed. The tissue was placed in a pre-cooled mortar at 4 °C, and 1 mL of pre-cooled phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) was added. The mixture was ground at low temperature until homogenized, then transferred to a centrifuge tube. The mortar was rinsed with 3 mL of phosphate buffer, and the rinse was also transferred to the centrifuge tube. The total volume was adjusted to 4 mL. After centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 20 min, the supernatant was collected for testing. The reagents and procedures provided in the SOD activity detection kit were followed to measure the autoxidation rate of pyrogallol. At approximately 25 °C, the blank contained all reagents except the enzyme extract, and the test contained the same reagents plus the enzyme extract. Using a 1 cm cuvette and distilled water as the blank, the absorbance values at 325 nm were immediately measured at 0 s, 30 s, 60 s, 90 s, 120 s, 150 s, and 180 s after adding the coloring solution. This was denoted as . The SOD inhibition rate of pyrogallol autoxidation was measured according to the reagents and procedures provided in the kit. The control and test groups were treated with reagents. Using a 1 cm cuvette and distilled water as the blank, the absorbance values at 325 nm were immediately measured after adding the coloring solution. This was denoted as :

where 1.8 mL is the total volume of the reaction mixture; V is the aliquot of enzyme extract (0.08 mL) used in the assay; D = 1 is the dilution factor; VT is the total volume of the enzyme extract (4.0 mL); and m = 0.4 g is the mass of the fresh sample.

2.2.4. Determination of Nutrient Content in Cotton Leaves

Determination of Soluble Sugar Content: The method for measuring soluble sugar content was based on Leach et al. [22]. A 10 mg/mL glucose stock solution was diluted with distilled water to prepare standard solutions of 0.2, 0.1, 0.05, 0.025, 0.0125, and 0.00625 mg/mL. A standard curve was plotted with the standard concentration on the x-axis and the corresponding absorbance on the y-axis to obtain the equation y = kx + b. The sample concentration x (mg/mL) was calculated by substitution into the equation. Fresh cotton leaves were cleaned to remove surface dirt, cut into small pieces and mixed well, and 0.1 g of plant sample was weighed. Then 1 mL of distilled water was added, and the sample was ground into a homogenate. The homogenate was heated at 95 °C for 10 min (sealed to prevent evaporation) and then cooled to room temperature. After centrifugation at 8000 rpm (room temperature, 10 min), the supernatant was collected as the sample solution. The reagents and procedures from the soluble sugar content detection kit were followed for control and sample tubes. The mixture was heated in a water bath at 95 °C for 10 min, cooled to room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 630 nm in a 1 cm cuvette (distilled water as blank):

where X is the sample concentration obtained from the standard curve (mg·mL−1); Vsample total is the total volume of the extracted sample (1.5 mL); D is the dilution factor (1); and W is the sample mass (0.1 g).

Determination of Amino Acid Content: Amino acid content was determined using the ninhydrin colorimetric method [23]. An amino acid standard solution (50 μg/mL) was diluted with chlorine-free distilled water to prepare standard solutions of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 μg/mL. The absorbance of each standard at 570 nm was measured (blank tube set to zero). A standard curve was plotted with the standard concentration on the x-axis and absorbance on the y-axis. Fresh cotton leaves were cleaned to remove surface dirt, cut into small pieces and mixed well, and 0.4 g of plant sample was weighed. Then 2 mL of 1× amino acid lysis buffer was added, and the sample was homogenized. The homogenate was diluted to 40 mL with distilled water, mixed well, and filtered through filter paper. The filtrate was stored at 4 °C as the crude amino acid extract. The reagents and procedures from the amino acid detection kit were followed for control and sample tubes. The mixture was heated at 80 °C for 20 min, then quickly cooled in an ice bath. Next, 2.1 mL of 60% ethanol was added and mixed well. The absorbance was immediately measured at 570 nm (blank set to zero):

where C is the amino acid concentration of the test tube obtained from the standard curve (μg/mL); VT is the total volume of the dilution sample (40 mL); and W is the fresh sample mass (0.2 g).

2.3. Data Processing

Experimental data were organized using Microsoft Excel 2021 and analyzed using SPSS 26.0. All data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance before analysis. Differences between the two cotton varieties at each sampling time were assessed using independent-sample t-tests. To examine changes over time within each variety, one-way analysis of variance was performed. Significant differences were considered at p < 0.05. Figures were produced using Origin 2022.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Cotton Aphid Feeding on the Activity of Protective Enzymes in Cotton Leaves

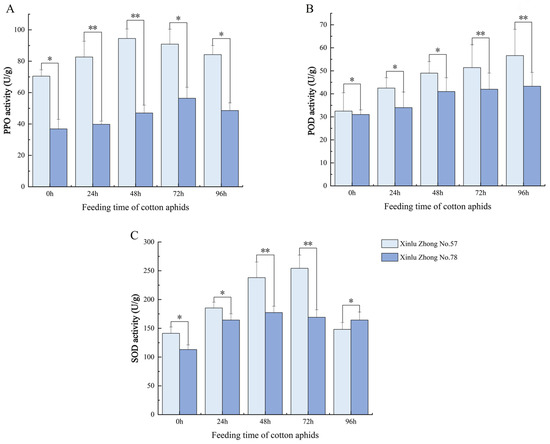

As shown in Figure 1, cotton aphid infestation significantly affected the activities of PPO, POD, and SOD in both cotton varieties (p < 0.05). The cotton aphid feeding caused a marked and rapid increase in PPO activity within 24 h. Throughout the experimental period, Xinlu Zhong 57 consistently exhibited higher PPO activity than Xinlu Zhong 78, and the difference between the two varieties was statistically significant (p < 0.05). PPO activity in Xinlu Zhong 57 peaked at 48 h, whereas Xinlu Zhong 78 reached a lower maximum at 72 h, followed by a gradual decline in both varieties by 96 h.

Figure 1.

Dynamic changes in protective enzyme activities in leaves of two cotton varieties under cotton aphid feeding. (A) PPO, (B) POD, and (C) SOD activities at different feeding times (0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h). Values are means ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between varieties at the same time point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

POD activity also increased progressively over the feeding period, reaching the highest level at 96 h (p < 0.05). At each time point, Xinlu Zhong 57 displayed higher POD activity than Xinlu Zhong 78, reflecting a stronger peroxidase-mediated defense response to cotton aphid stress. Similarly, cotton aphid feeding induced a pronounced increase in SOD activity in both varieties. Xinlu Zhong 57 showed a more intense and prolonged SOD response, peaking at 72 h, while Xinlu Zhong 78 peaked earlier at 48 h and then declined.

Overall, cotton aphid feeding induced pronounced activation of antioxidant enzymes in cotton leaves, and Xinlu Zhong 57 displayed significantly higher PPO, POD, and SOD activities than Xinlu Zhong 78 across all time points (p < 0.05), suggesting a more robust antioxidative defense mechanism against cotton aphid stress.

3.2. Effects of Cotton Aphid Feeding on Secondary Metabolites in Cotton Leaves

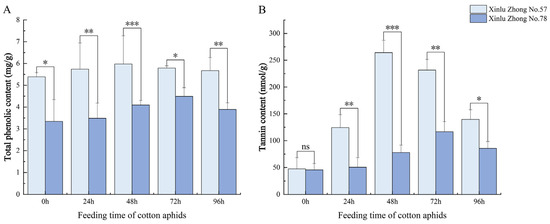

As shown in Figure 2, cotton aphid feeding markedly affected the accumulation of phenolic secondary metabolites in cotton leaves. The total phenolic content increased significantly within 24 h in both varieties (p < 0.05). Throughout the feeding period, Xinlu Zhong 57 consistently exhibited higher total phenolic levels than Xinlu Zhong 78. The phenolic content of Xinlu Zhong 57 reached its maximum at 48 h, while Xinlu Zhong 78 peaked later at 72 h with a lower amplitude. Although the phenolic content of both varieties declined slightly by 96 h, Xinlu Zhong 57 maintained significantly higher levels than Xinlu Zhong 78 at all time points (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Dynamic changes in phenolic secondary metabolite content in leaves of two cotton varieties under cotton aphid feeding. (A) Total phenolic content and (B) tannin content measured at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of cotton aphid feeding. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between varieties at the same time point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). “ns” indicates no significant difference between different varieties at the same time point (p > 0.05).

The cotton aphid feeding also induced significant changes in tannin accumulation (Figure 2B). In both varieties, tannin content increased sharply during the early stages of infestation, reaching the highest level between 48 h and 72 h (p < 0.05). However, Xinlu Zhong 57 consistently accumulated more tannins than Xinlu Zhong 78, and the difference between the two varieties was statistically significant at most sampling times (p < 0.05). By 96 h, tannin content declined in both varieties, but Xinlu Zhong 57 still maintained a markedly higher concentration, indicating a stronger and more sustained secondary metabolic response to cotton aphid stress.

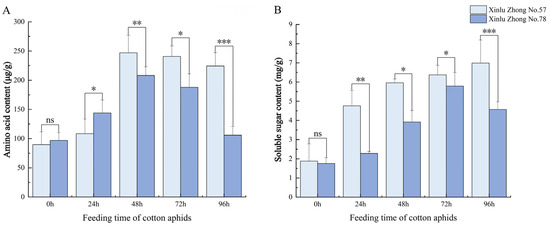

3.3. Effects of Cotton Aphid Feeding on Nutritional Substances in Cotton Leaves

As shown in Figure 3, cotton aphid feeding significantly influenced the accumulation of amino acids and soluble sugars in cotton leaves (p < 0.05). Both Xinlu Zhong 57 and Xinlu Zhong 78 exhibited significant increases in amino acid content after 24 h of cotton aphid feeding. Xinlu Zhong 57 consistently showed higher amino acid content than Xinlu Zhong 78 throughout the experiment. The maximum amino acid accumulation occurred at 48 h, with Xinlu Zhong 57 reaching 247.1 μg/g, while Xinlu Zhong 78 peaked at 208.2 μg/g, with a significant difference between them (p < 0.05). By 96 h, both varieties exhibited a decline in amino acid content, but the difference remained significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Dynamic changes in nutrient content in the leaves of two cotton varieties induced by cotton aphid feeding. (A) Amino acid content and (B) soluble sugar content measured at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of cotton aphid feeding. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between varieties at the same time point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).“ns” indicates no significant difference between different varieties at the same time point (p > 0.05).

Similarly, cotton aphid feeding induced a pronounced increase in soluble sugar content (Figure 3B). Both varieties showed a significant increase in soluble sugars after 24 h (p < 0.05), with Xinlu Zhong 57 accumulating significantly more than Xinlu Zhong 78. At 48 h, Xinlu Zhong 57 reached 5.96 mg/g, while Xinlu Zhong 78 reached 3.92 mg/g, with a significant difference (p < 0.05). By 96 h, Xinlu Zhong 57 maintained its peak concentration of 6.99 mg/g, while Xinlu Zhong 78 decreased to 4.57 mg/g, showing a significant difference between the varieties (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Cotton aphids feed mainly on the sap of cotton leaves, and continuous feeding can cause leaf curling, nutrient loss, and reduced photosynthetic efficiency. When plants are subjected to pest stress, they adapt to adverse conditions and survive by inducing secondary metabolite production and related signaling responses [24]. This study reveals differences between cotton varieties under cotton aphid stress in three aspects: phenolic secondary metabolites, defensive enzyme activity changes, and nutrient allocation. The results indicate that both Xinlu Zhong 57 and Xinlu Zhong 78 possess some resistance after cotton aphid stress, but Xinlu Zhong 57 responds faster and more strongly, suggesting a higher cotton aphid resistance potential.

Phenolic metabolites, including tannins and total phenols, play a critical role in cotton’s defense against cotton aphids by reducing cotton aphid palatability and inhibiting reproduction [7,25]. In this experiment, tannin and total phenol levels in Xinlu Zhong 57 peaked at 48 h after cotton aphid feeding, significantly higher than those in Xinlu Zhong 78, indicating that the former can rapidly mobilize defensive metabolites in the early phase. This trend is consistent with observations in sugarcane cotton aphid resistance research by Zhao et al. [26]. Combined with recent studies on regulatory genes [8,9], it can be speculated that accumulation of these phenolic compounds is closely related to phenylpropanoid metabolism and transcription factor regulation. Stronger regulatory capacity likely leads to faster and greater accumulation of phenolic defense substances, and thus greater cotton aphid resistance potential in cotton.

The cotton aphid damage often leads to rapid accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant tissues, and the defensive enzyme system is an important pathway for ROS scavenging [6]. In this study, SOD, POD, and PPO activities in Xinlu Zhong 57 were higher than those in Xinlu Zhong 78, and they followed a pattern of an initial rise and then fall. This indicates that the more resistant variety can quickly alleviate oxidative damage in the short term and maintain a relatively stable state at later stages. A similar induction pattern has been reported in the pea aphid-mung bean system [27]. When mung beans are attacked by pea aphids, PPO activity increases significantly, accompanied by accumulation of phenolic metabolites related to insect resistance. This suggests that enhancing oxidative detoxification via the PPO pathway may be a conserved cotton aphid resistance mechanism in leguminous plants. This is consistent with findings in the cotton-aphid system here, collectively highlighting the importance and ubiquity of PPO induction as an early insect resistance signal in plants. Recent studies have shown that resistant varieties usually have advantages in ROS clearance ability and the magnitude of enzyme system induction [28]. In addition, POD promotes lignin synthesis to strengthen cell walls, and PPO can convert phenols into quinones that bind to proteins to reduce palatability-both processes play important roles in cotton’s resistance to cotton aphids [29,30].

In addition to chemical defenses and enzyme activity regulation, changes in nutrients are key factors affecting resistance. This study showed that soluble sugar levels in Xinlu Zhong 57 continued to rise after cotton aphid feeding, whereas those in Xinlu Zhong 78 decreased significantly after 72 h. This indicates that high sugar accumulation in plant tissues reduces cotton aphid feeding suitability by increasing phloem sap osmotic pressure and raising the excretion burden of honeydew [31]. This result is consistent with observations by Slosser et al. [32] and Gao et al. [33], who reported that cotton aphid populations in cotton fields are negatively correlated with leaf sugar content. Our study further elucidates a potential mechanism whereby high sugar content directly affects cotton aphid feeding behavior from physiological and ecological perspectives-namely, by imposing osmotic stress and increasing energy expenditure in cotton aphids, thereby weakening their fitness. In terms of amino acids, Xinlu Zhong 57 maintained higher levels than Xinlu Zhong 78 at later stages, which is speculated to be related to the accumulation of defense-related amino acids such as proline and glutamic acid. Proline has been shown to limit cotton aphid colonization and development [34], while increased glutamic acid enhances plant resistance [35], suggesting that resistant varieties manage nutrient allocation to inhibit cotton aphid feeding while maintaining their own growth.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically compared the chemical defense responses of the two main cotton cultivars, Xinlu Zhong 57 and 78 in the Kashi region to cotton aphid feeding stress. The results showed that both cultivars exhibited a dynamic change trend of “first increasing and then decreasing” in the content of secondary metabolites and the activity of protective enzymes. However, Xinlu Zhong 57 demonstrated an earlier and stronger comprehensive resistance mechanism. Its tannin and total phenol contents reached a peak at 48 h after cotton aphid infestation, with significantly higher accumulation levels than Xinlu Zhong 78 Meanwhile, the activities of SOD, POD, and PPO in Xinlu Zhong 57 were maintained at a higher level throughout the stress period, indicating a stronger ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species and alleviate oxidative stress. In terms of nutrients, the soluble sugar content of Xinlu Zhong 57 continued to increase, and its amino acid content was significantly higher than that of the control variety in the later stage of cotton aphid infestation, reflecting its physiological flexibility in nutrient allocation. In summary, Xinlu Zhong 57 formed a more coordinated and effective chemical defense system by rapidly activating the defense enzyme system, efficiently accumulating secondary metabolites, and optimizing nutrient allocation strategies. This study provides a theoretical basis for elucidating the physiological mechanisms of the induced resistance of cotton to cotton aphids and has important reference value for the breeding of cotton aphid-resistant varieties and the practice of green pest control in the southern Xinjiang cotton region.

However, this study also has certain limitations. The number of cotton cultivars selected was relatively small, and the cotton aphid feeding time was relatively short, which may have limited the complete revelation of the entire process of the chemical response mechanism to cotton aphid feeding. Future research can expand the range of cotton cultivars selected and extend the cotton aphid feeding time to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the entire process of the chemical response mechanism to cotton aphid feeding and further optimize the cotton aphid resistance traits of cotton.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; Methodology, P.X., J.D. and X.W. Investigation, H.L., W.G. and B.F. Data Curation, S.W. and P.X. Formal Analysis, P.X. and X.W.; Visualization, P.X.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, P.X. and J.D.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.S.; Supervision, S.S.; Project Administration, S.S.; Funding Acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Monitoring and Key Technology Research and Demonstration of Cotton Aphid Resistance in the Kashi Region (Grant No. KS2024002); Investigation of Population Dynamics and Monitoring of Cotton Aphid Resistance in the Kashi Region (Grant No. S202510763046); and the Talent Introduction Start-up Fund of Kashi University (Grant No. GCC2023ZK-007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The cotton aphids used in this study were standard laboratory-reared, and the experimental procedures did not involve any actions likely to cause pain, distress, or lasting harm.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by the School of Modern Agriculture, Kashi University. We also thank the field management team for their assistance during the cultivation and sampling process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fang, L.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Chen, J.D.; Liu, B.L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Guan, X.Y.; Chen, S.Q.; Zhou, B.L. Genomic analyses in cotton identify signatures of selection and loci associated with fiber quality and yield traits. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, W.; Devadoss, S. Competition and trade policy in the world cotton market: Implications for US cotton exports. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2023, 105, 1365–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, S.; Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Ai, N.; Guan, X. The impact of temperature on cotton yield and production in Xinjiang, China. npj Sustain. Agric. 2024, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Xu, Y.H.; Gao, Y.G.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, A.H.; Zang, L.S.; Wu, C.S.; Zhang, L.X. Panaxadiol saponins treatment caused the subtle variations in the global transcriptional state of Asiatic corn borer, Ostrinia furnacalis. J. Ginseng Res. 2020, 44, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Huang, J.M.; Ni, H.G.; Guo, D.Y.; Yang, F.X.; Wang, X.W.; Wu, S.F.; Gao, C.F. Susceptibility of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith), to eight insecticides in China, with special reference to lambda-cyhalothrin. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 168, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, H.Q.; Chen, L.S.; Wang, P.L.; Li, J. Correlation Between Induced Resistance to Aphids and Secondary Metabolism Enzyme Activities of Cotton Varieties in Xinjiang. Plant Prot. 2017, 43, 51–55+96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, T.C.; Katageri, I.S.; Jadhav, M.P.; Adiger, S.; Vamadevaiah, H.M.; Olekar, N.S. Biochemical constituents imparting resistance to sucking pest aphid in cotton (Gossypium spp.). Int. J Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 2749–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.W.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, H.R.; Luo, X.C.; Wang, Y.X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.P.; An, H.L. GhMYB18 confers Aphis gossypii Glover resistance through regulating the synthesis of salicylic acid and flavonoids in cotton plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, T.; Luo, X.C.; Wang, Y.; Chu, L.Y.; Li, J.P.; An, H.L.; Wan, P.; Xu, D. GhMYC1374 regulates the cotton defense response to cotton aphids by mediating the production of flavonoids and free gossypol. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 205, 108162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.H.; Patima, U.; Cui, Y.H.; Li, Y.; Feng, H.Z. The effect of cotton aphid feeding on the defensive enzyme activity of different cotton varieties. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2015, 52, 1866–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patima, U.; Ma, S.J.; Guo, P.P.; Wu, M.M.; Liu, F.; Ma, D.Y. Effects of Aphis gossypii feeding stresses with different densities on soluble sugar and free proline contents in cotton leaves. J. Xinjiang Agric. Univ. 2018, 41, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N.; Zang, Y.D.; Cai, X.H.; Shi, Y.H.; Han, R.; Wang, J.G. The activity of related enzymes in cotton is affected after cotton aphids feed on it, which is harmed by cotton long-tubed aphids. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2020, 57, 2056–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.P.; Ma, Y.X.; Gu, X.; Wang, X.P. Chemical defense response of four Lycium barbarum varieties to feeding by cotton aphid. Plant Prot. 2025, 51, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.N.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.J.; Kong, Z.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Q.C.; Cheng, S.H.; Qin, P. Combined transcriptome and metabolome analysis of the resistance mechanism of quinoa seedlings to Spodoptera exigua. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 931145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.B.; Fang, L.P.; Lv, Z.Z.; Zang, Z. Relationships between the cotton resistance to the cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii) and the content of soluble sugars. Plant Prot. 2008, 34, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.J.; Ren, F.P.; Gao, L. Testing Methods of the Vegetable Tannin Content. Westleather 2010, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.H.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.G. Research on the extraction process of total phenols from reed leaves and its antioxidant properties. Anhui Chem. Ind. 2024, 50, 29–33+39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.S. Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Experiments; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 164–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.Y. Optimization of Determination Method of Peroxidase Activity in Plant. Res. Explor. Lab. 2010, 29, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.X.; Ying, W.; Huang, Y.Q.; Xu, S.C.; Ruan, S.S.; Zhang, S. Effects of Plant Immune Inducers on the Growth of Soybean Seedlings. Soybean Sci. 2024, 43, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Peng, J.; Wang, J. Protective enzyme activity regulation in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) in response to Scirpus planiculmis stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1068419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, K.A.; Braun, D.M. Soluble Sugar and Starch Extraction and Quantification from Maize (Zea mays) Leaves. Curr. Protoc. Plant Biol. 2016, 1, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.P.; Yu, H.M.; Cai, D.L.; Fan, S.M.; Liu, W.W.; Yang, C.Z.; Lin, Y. Detection of total amino acids of Pholidota cantonensis Rolfe from Fujian province by ninhydrin colorimetric method. J. Bengbu Med. Univ. 2024, 49, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.H.; Kang, Z.W.; Hu, X.S.; Zhang, Z.F.; Liu, T.X. Effects of foliage nutrients of different wheat cultivars on the grain aphid, Sitobion avenae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Plant Prot. 2017, 44, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.S.; Tang, Q.L.; Liang, P.Z.; Xia, J.Z.; Zhang, B.Z.; Gao, X.W. Toxicity and sublethal effects of two plant allelochemicals on the demographical traits of cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.Y.; Zhou, Y.S.; Su, L.Y.; Li, G.H.; Huang, Z.Z.; Huang, D.Y.; Wu, W.M.; Zhao, Y. Expression of Pinellia pedatisecta agglutinin PPA gene in transgenic sugarcane led to stomata patterning change and resistance to sugarcane woolly aphid, Ceratovacuna lanigera Zehntner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.Y.; Jin, Y.L.; Zhang, H.Y.; Liu, R.; Sun, Y.J.; Guo, S.M.; Zeng, Y.T.; Wang, L.Y. Effects of Aphis craccivora Koch Infestation on the Nutrient Contents and Protective Enzyme Activities in Mung Bean Resistant and Susceptible Varieties. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2020, 49, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Mandhania, S.; Pal, A.; Kaur, T.; Banakar, P.; Sankaranarayanan, K.; Arya, S.S.; Malik, K.; Datten, R. Morpho-physiological and biochemical responses of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) genotypes upon sucking insect-pest infestations. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 2023–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thipyapong, P.; Stout, M.J.; Attajarusit, J. Functional analysis of polyphenol oxidases by antisense/sense technology. Molecules 2007, 12, 1569–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, A.R.; Paulraj, M.G.; Ahmad, T.; Buhroo, A.A.; Hussain, B.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Sharma, H.C. Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1306–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Wu, N.; Zhang, Y.D.; Han, R.; Zhang, Q.C.; Wang, J.G. Effects of aphid damage to cotton plants on the nutritionalmetabolism of Aphis gossypii. Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2022, 59, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slosser, J.E.; Parajulee, M.N.; Hendrix, D.L.; Henneberry, T.J.; Pinchak, W.E. Cotton aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) abundance in relation to cotton leaf sugars. Environ. Entomol. 2004, 33, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Z. Effects of saline-alkali stress on cotton growth and aphid (Aphis gossypii) infestation: Mechanistic insights into soluble sugar and secondary metabolites in leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1459654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, J.Y.; Zhang, X.Z.; Gao, X.K.; Cui, J.J. Regulation of Free Amino Acid in Cotton at the Seedling Stage by Aphis gossypii Feeding. Cotton Sci. 2020, 32, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).