Hydroponic and Soil-Based Screening for Salt Tolerance and Yield Potential in the Different Growth Stages of Thai Indigenous Lowland Rice Germplasm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment 1 Hydroponic Screening

2.2. Experiment 2 Responses in Growth and Ion Concentration of Selected Varieties of Rice Germplasm to Different Soil Salinity Media and Growth Stage

2.3. Data Analysis

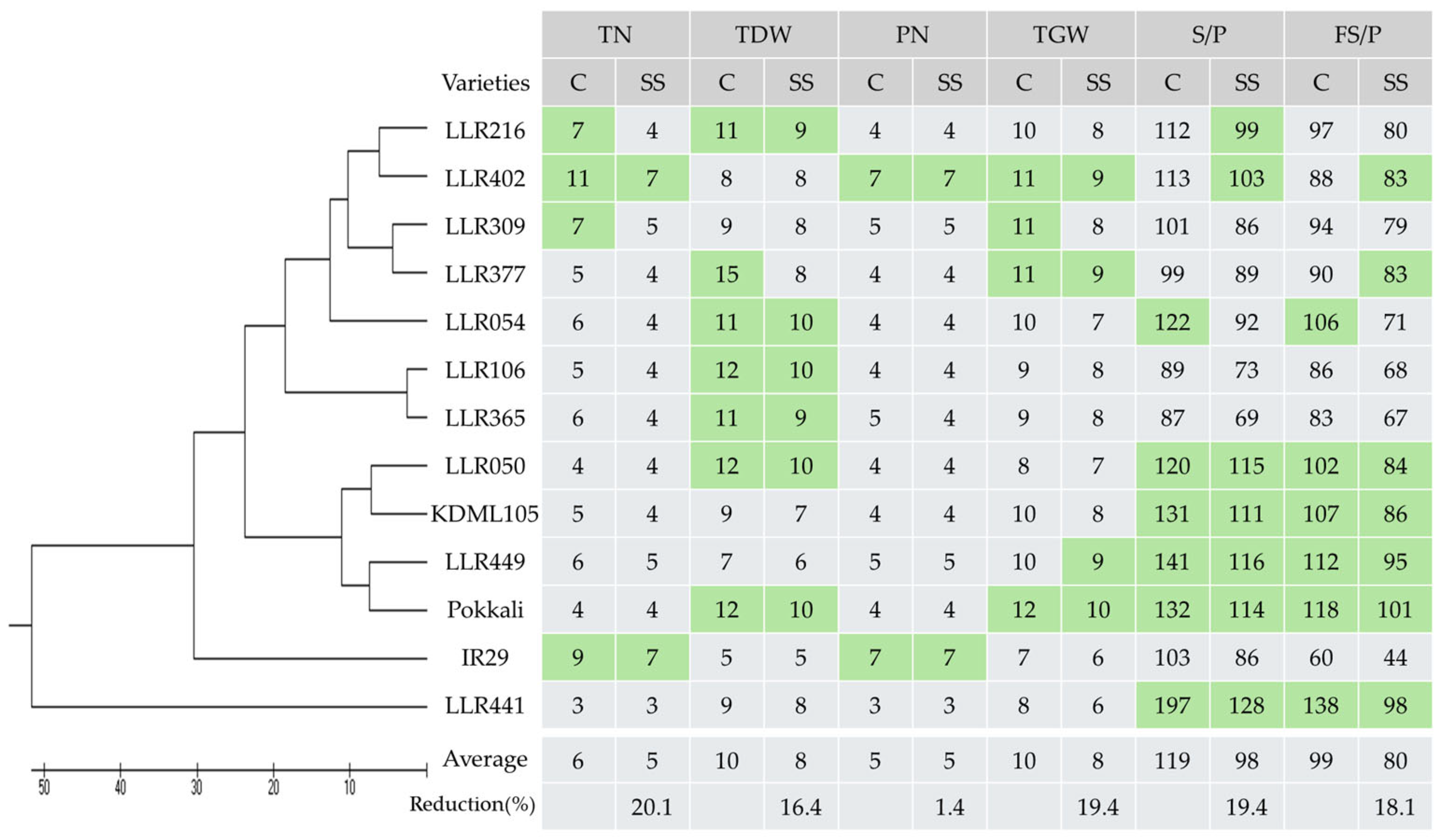

3. Results

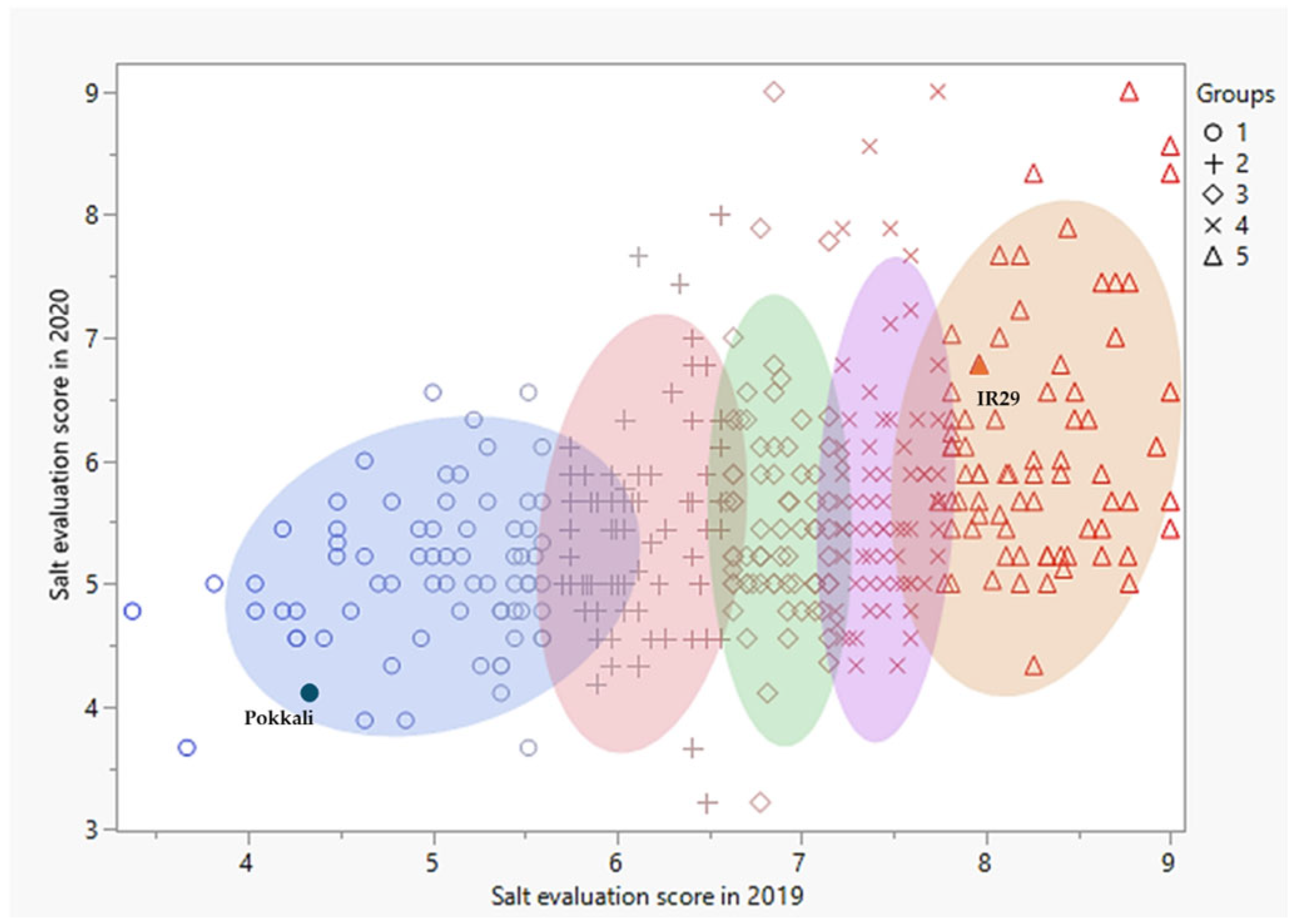

3.1. Solution Conditions

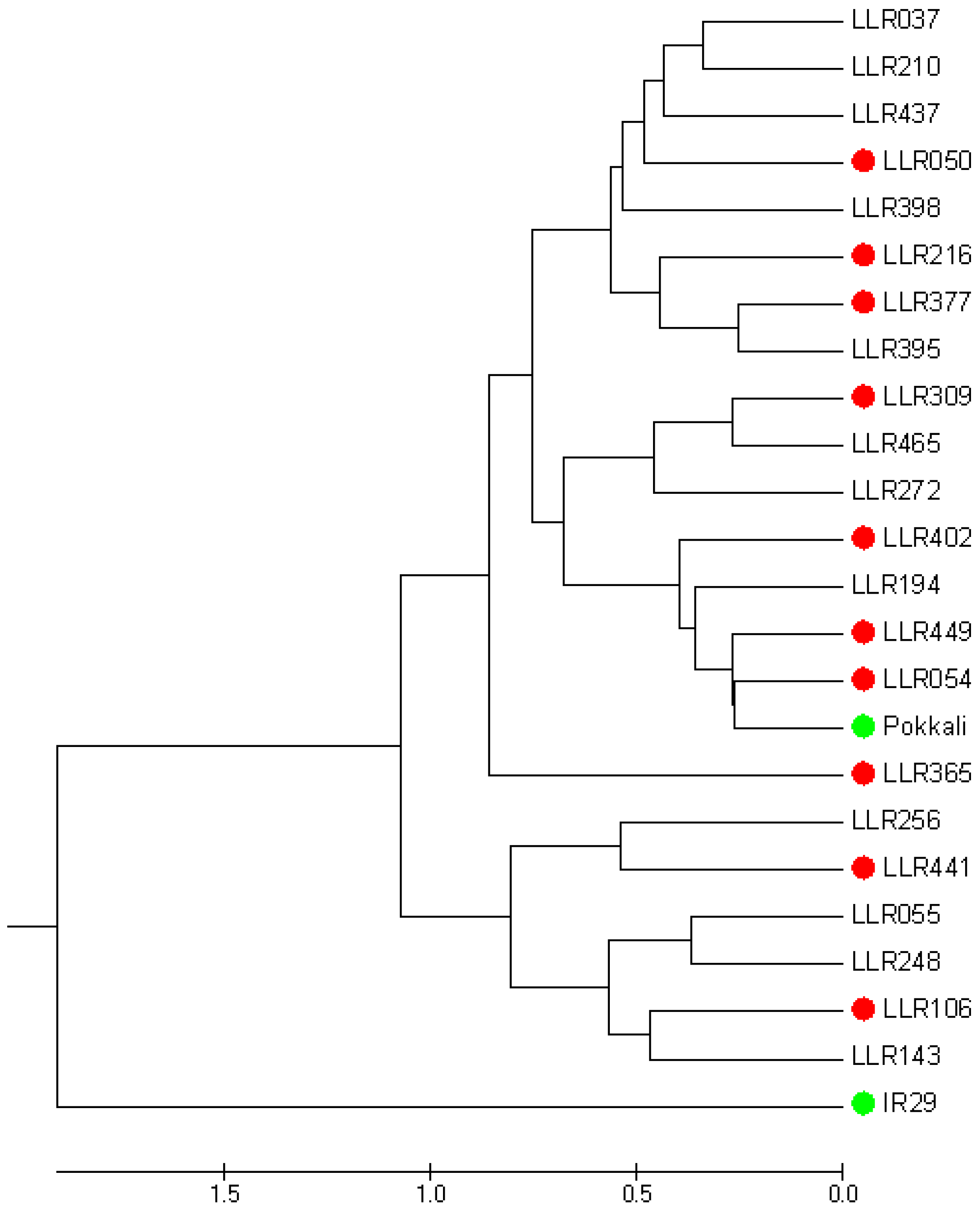

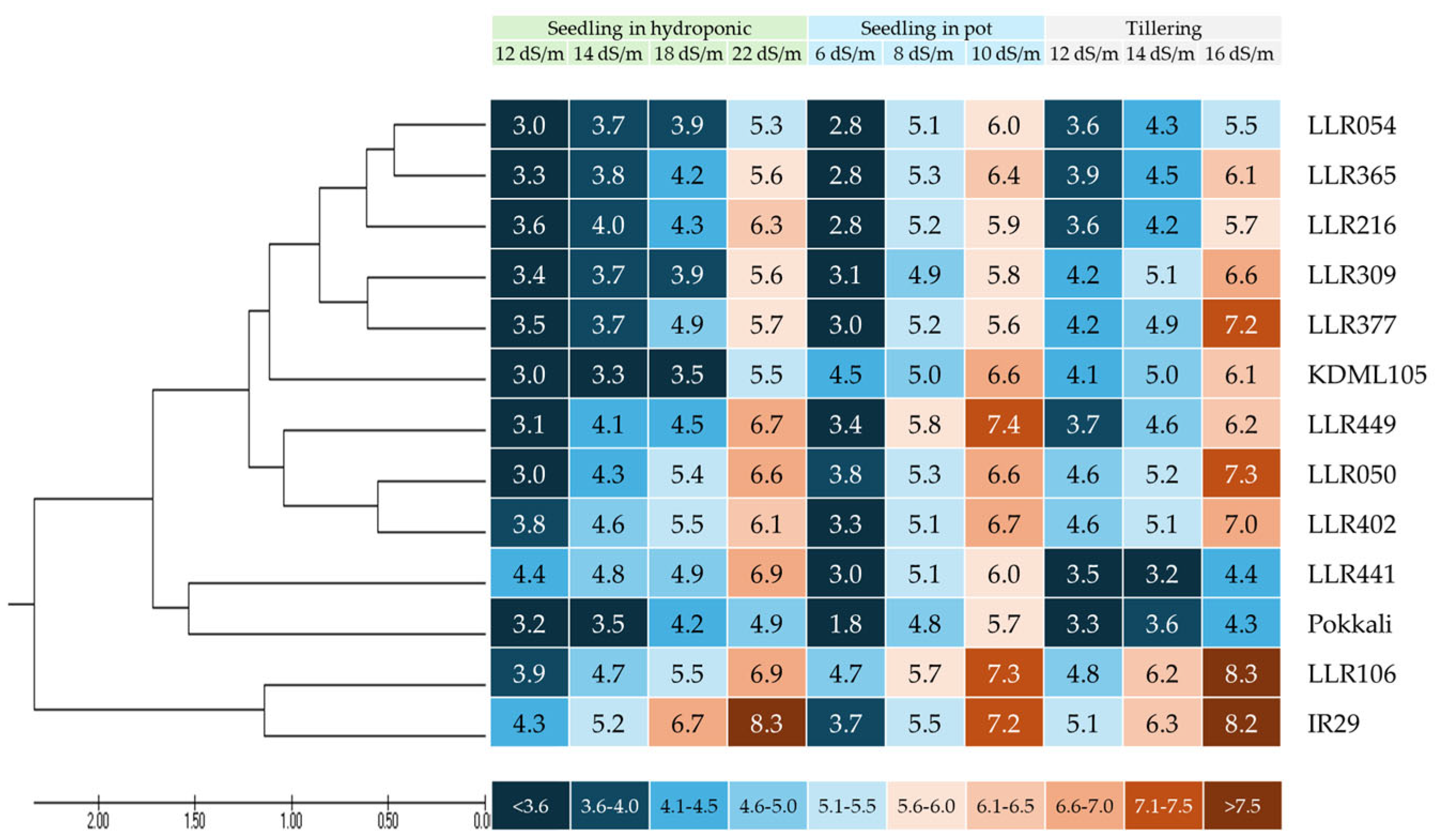

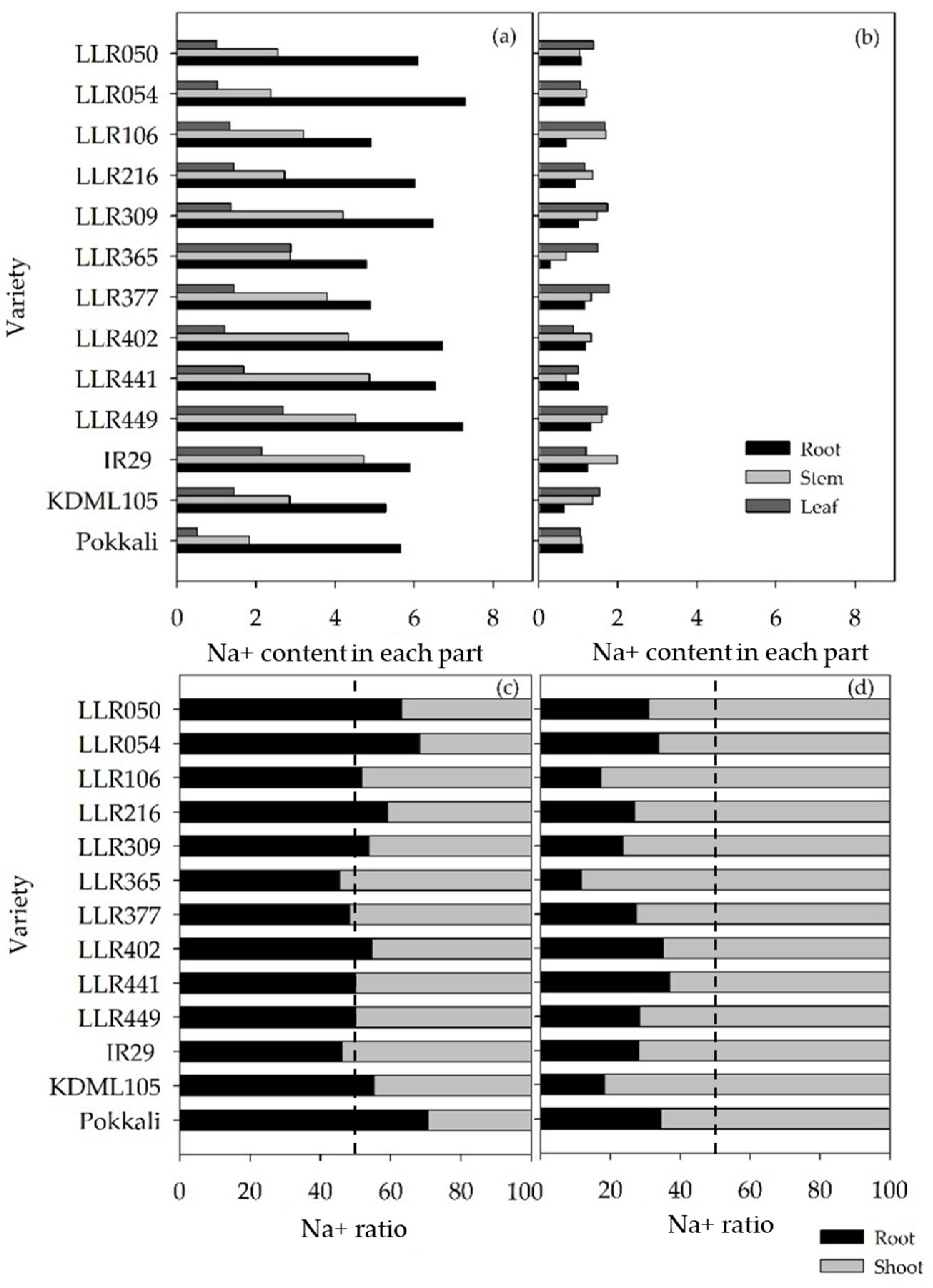

3.2. Evaluation of the Salt-Tolerant Rice Varieties in Different Media and Stages

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Office of Agricultural Economics. Agricultural Statistics of Thailand. 2022. Available online: https://www.oae.go.th/assets/portals/1/files/jounal/2566/yearbook2565.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Suebpongsang, P.; Ekasingh, B.; Cramb, R. Commercialisation of rice farming in northeast Thailand. In White Gold: The Commercialisation of Rice Farming in the Lower Mekong Basin; Gateway East: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, J.; Hirose, M.; Tanaka, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Nakao, A.; Dejbhimon, K.; Sriprachote, A.; Kanyawongha, P.; Lattirasuvan, T.; Abe, S. Changes in paddy soil fertility in Thailand due to the Green Revolution during the last 50 years. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 66, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwongchai, W.; Tananuwong, K.; Krusong, K.; Thitisaksakul, M. Yield, grain quality, and starch physicochemical properties of 2 elite Thai rice cultivars grown under varying production systems and soil characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, L.S. Report of Investigation—Thailand, Department of Mineral Resources; Thailand Department of Mineral Resources: Bangkok, Thailand, 1967; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Arunin, S.; Pongwichian, P. Salt-affected soils and management in Thailand. Bull. Soc. Sea Water Sci. 2015, 69, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Ye, R.; Srisutham, M.; Nontasri, T.; Sritumboon, S.; Maki, M.; Yoshida, K.; Oki, K.; Homm, K. Rice production in farmer fields in soil salinity classified areas in Khon Kaen, Northeast Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanism of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.; Jini, D.; Sujatha, S. Biological and physiological perspectives of specificity in abiotic salt stress response from various. Asian J. Agric. Sci. 2010, 2, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Aref, F.; Ebrahimi-Rad, H. Physiological characterization of rice under salinity stress during vegetative and reproductive stages. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2012, 5, 2578–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Shannon, M.C. Salinity effects on seedling growth and yield components of rice. Crop Sci. 2000, 40, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Shannon, M.C.; Lesch, S.M. Timing of salinity stress affects rice growth and yield components. Agric. Water Manag. 2001, 48, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, T.U.; Akhtar, J.; Nawaz, S.; Ahmad, R. Morpho-physiological response of rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties to salinity stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 2943–2956. [Google Scholar]

- Heenan, D.P.; Lewin, L.G.; McCaffery, D.W. Salinity tolerance in rice varieties at different growth stages. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1988, 28, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Zhang, X.; Ge, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wei, H.; Dai, Q. Agronomic and physiological traits facilitating better yield performance of japonica/indica hybrids in saline fields. Field Crops Res. 2021, 271, 108255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.M.; Horie, T. Genomics, physiology, and molecular breeding approaches for improving salt tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 405–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, J.; Nazim, H.; Cai, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, B.; Haider, S.I.; Zhang, G. The influence of salinity on cell ultrastructures and photosynthetic apparatus of barley genotypes differing in salt stress tolerance. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Chakraborty, K.; Mondal, S.; Jena, P.; Panda, R.K.; Samal, K.C.; Chattopadhyay, K. Relative contribution of ion exclusion and tissue tolerance traits govern the differential response of rice towards salt stress at seedling and reproductive stages. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 206, 105131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, G.; Song, X.; Ibrahim, M.E.H.; Salih, E.G.I. Effect of N on growth, antioxidant capacity, and chlorophyll content of sorghum. Agronomy 2022, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.M.L.; Moghaddam, L.; Williams, B.; Khanna, H.; Dale, J.; Mundree, S.G. Development of salinity tolerance in rice by constitutive-overexpression of genes involved in the regulation of programmed cell death. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisham, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Bhatla, S.C. Mechanisms of Sodium Transport in Plants—Progresses and Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fita, A.; Rodríguez-Burruezo, A.; Boscaiu, M.; Prohens, J.; Vicente, O. Breeding and domesticating crops adapted to drought and salinity: A new paradigm for increasing food production. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Ceccarelli, S.; Blair, M.W.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Are, A.K.; Ortiz, R. Landrace germplasm for improving yield and abiotic stress adaptation. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Forno, D.A.; Cock, J.H.; Gomez, K.A. Routine Procedures for Growing Rice Plants in Culture Solution; Laboratory Manual for Physiological Studies of Rice; IRRI: Manila, Philippines, 1976; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Shavrukov, Y. Salt stress or salt shock: Which genes are we studying? J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Standard Evaluation System for Rice, 5th ed.; The International Rice Research Institute: Manila, Philippines, 2013; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dionisio-Sese, M.L.; Tobita, S. Antioxidant responses of rice seedlings to salinity stress. Plant Sci. 1998, 135, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analytical Software. Statistix (Version 10) [Computer Software]; Analytical Software: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sneath, P.H.A.; Sokal, R.R. Numerical Taxonomy: The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. W. H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A Review on Plant Responses to Salt Stress and Their Mechanisms of Salt Resistance. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Shabala, S.; Niu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shabala, L.; Meinke, H.; Venkataraman, G.; Pareek, A.; Xu, J.; Zhou, M. Molecular mechanisms of salinity tolerance in rice. Crop J. 2021, 9, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Mo, J.; Zhou, H.; Shen, X.; Xie, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, S. Comparative transcriptome analysis of gene responses of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive rice cultivars to salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.H.; Fu, B.Y.; Xu, H.X.; Zhu, L.H.; Zhai, H.Q.; Li, Z.K. Cell death in response to osmotic and salt stresses in two rice (Oryza sativa L.) ecotypes. Plant Sci. 2007, 172, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Jiang, A.L.; Zhang, W. Salt stress-induced programmed cell death in rice root tip cells. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007, 49, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Srivastava, A.K.; Sharma, D.; Pandey, S.P.; Pandey, M.; Dudwadkar, A.; Parab, H.J.; Suprasanna, P.; Das, B.K. Antioxidant defense and ionic homeostasis govern stage-specific response of salinity stress in contrasting rice varieties. Plants 2024, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Espín, G.; Clemente-Moreno, M.J.; Álvarez, S.; García-Legaz, M.F.; Hernandez, J.A.; Diaz-Vivancos, P. Salicylic acid negatively affects the response to salt stress in pea plants. Plant Biol. 2011, 13, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Shaw, B.P. Biochemical and molecular characterisations of salt tolerance components in rice varieties tolerant and sensitive to NaCl: The relevance of Na+ exclusion in salt tolerance in the species. Funct. Plant Biol. 2020, 48, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bu, W.; Xu, Y.; Fei, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ahmad, I.; Nimir, N.E.A.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, G. Effects of Salt Stress on Physiological and Agronomic Traits of Rice Genotypes with Contrasting Salt Tolerance. Plants 2024, 13, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunkao, S.; Theerakulpisut, P. Effects of salinity on photosynthesis and growth of rice and alleviation of salt-stress by exogenous spermidine. Khon Kaen Agric. J. 2019, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Santanoo, S.; Lontom, W.; Dongsansuk, A.; Vongcharoen, K.; Theerakulpisut, P. Photosynthesis performance at different growth stages, growth, and yield of rice in saline fields. Plants 2023, 12, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, M.; Davenport, R. Na+ tolerance and Na+ transport in higher plants. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.H.; Panda, S.K. Alterations in root lipid peroxidation and antioxidative responses in two rice cultivars under NaCl salinity stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2008, 30, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, B.; Sudiro, C.; Jabir, R.; Schiavo, F.L.; Hyder, M.Z.; Yasmin, T. Adaptive behaviour of roots under salt stress correlates with morpho-physiological changes and salinity tolerance in rice. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2019, 21, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.K.; Flowers, T.J. The physiology and molecular biology of the effects of salinity on rice. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, 3rd ed.; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 899–942. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, R.; Mendioro, M.S.; Diaz, G.Q.; Gregorio, G.B.; Singh, R.K. Genetic analysis of salt tolerance at seedling and reproductive stages in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Breed. 2014, 133, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment | Year | Condition | Plant Stage | No. Varieties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | 2019 and 2020 | Hydroponic | Seedling | 382 |

| Experiment 2 | 2021 and 2022 | Hydroponic | Seedling | 22 |

| 2023 | Hydroponic | Seedling | 10 | |

| 2023 | Soil | Seedling | 10 | |

| 2023 | Soil | Tillering | 10 | |

| 2023 | Soil | Flowering | 10 |

| 2021 | 2022 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varieties | 12 (dS/m) 1 | 14 (dS/m) | 18 (dS/m) | 22 (dS/m) | 12 (dS/m) | 14 (dS/m) | 18 (dS/m) | 22 (dS/m) |

| LLR037 | 2.17 b–f | 3.5 b–e | 3.63 b–e | 4.04 def | 2.37 | 3.80 | 5.16 a–e | 6.02 b–f |

| LLR050 | 2.60 abc | 3.50 b–e | 3.88 b–e | 4.17 cde | 2.90 | 3.81 | 4.82 b–e | 5.56 c–h |

| LLR054 | 2.22 b–f | 3.38 b–e | 3.25 b–e | 3.34 fg | 2.07 | 3.32 | 4.27 de | 5.00 fgh |

| LLR055 | 2.52 a–d | 3.88 abc | 4.03 abc | 4.23 b–e | 3.14 | 4.61 | 5.67 abc | 6.53 a–d |

| LLR106 | 2.57 abc | 3.60 b–e | 3.97 b–e | 4.60 bcd | 2.56 | 3.80 | 5.51 a–d | 6.69 abc |

| LLR143 | 2.07 b–f | 3.46 b–e | 3.78 b–e | 4.21 b–e | 2.80 | 4.13 | 5.93 ab | 6.95 ab |

| LLR194 | 2.17 b–f | 3.25 def | 3.38 def | 4.03 def | 1.93 | 3.33 | 4.14 e | 5.29 d–h |

| LLR210 | 2.13 b–f | 3.28 c–f | 3.50 c–f | 3.83 d–g | 2.61 | 4.03 | 4.68 b–e | 5.91 b–h |

| LLR216 | 1.79 def | 3.61 bcd | 3.83 bcd | 4.65 bcd | 2.68 | 4.07 | 4.47 cde | 5.22 e–h |

| LLR248 | 2.63 abc | 3.53 b–e | 3.98 b–e | 4.62 bcd | 3.21 | 4.69 | 5.22 a–e | 6.74 abc |

| LLR256 | 2.80 ab | 3.60 b–e | 4.10 b–e | 5.00 ab | 2.03 | 3.47 | 4.78 b–e | 6.47 b–e |

| LLR272 | 2.60 abc | 3.73 a–d | 4.20 a–d | 4.54 bcd | 1.84 | 3.50 | 4.32 de | 5.15 fgh |

| LLR309 | 2.40 a–d | 3.65 bcd | 3.83 bcd | 4.50 bcd | 2.27 | 3.20 | 4.02 e | 4.60 h |

| LLR365 | 1.52 f | 2.98 ef | 3.09 ef | 3.10 g | 2.85 | 3.70 | 4.43 cde | 5.63 c–h |

| LLR377 | 2.27 b–f | 3.38 b–e | 3.60 b–e | 4.37 b–e | 2.12 | 3.72 | 4.63 cde | 5.36 d–h |

| LLR395 | 2.10 b–f | 3.43 b–e | 3.85 b–e | 4.58 bcd | 2.28 | 3.70 | 4.72 b–e | 5.65 c–h |

| LLR398 | 2.03 c–f | 2.75 f | 3.60 f | 3.93 def | 2.39 | 3.68 | 4.84 b–e | 5.53 c–h |

| LLR402 | 1.63 ef | 3.25 def | 3.73 def | 3.83 d–g | 2.32 | 3.43 | 4.28 de | 4.99 fgh |

| LLR437 | 2.30 b–e | 3.38 b–e | 3.45 b–e | 4.23 b–e | 2.89 | 4.16 | 5.45 a–d | 6.12 b-f |

| LLR441 | 2.31 b–e | 3.90 ab | 4.35 ab | 4.97 abc | 2.70 | 3.82 | 4.85 b–e | 6.04 b–f |

| LLR449 | 1.97 c–f | 3.23 def | 3.45 def | 3.57 efg | 1.97 | 3.33 | 4.45 cde | 5.23 e–h |

| LLR465 | 2.00 c–f | 3.50 b–e | 4.08 b–e | 4.50 bcd | 2.13 | 3.27 | 4.07 e | 4.72 gh |

| Pokkali (Tolerant control) | 1.98 c–f | 3.16 def | 3.24 def | 3.59 efg | 2.39 | 3.29 | 4.30 de | 4.99 fgh |

| IR29 (Susceptible control) | 3.10 a | 4.28 a | 5.05 a | 5.67 a | 3.48 | 4.62 | 6.18 a | 7.78 a |

| Mean | 2.24 | 3.47 | 3.78 | 4.25 | 2.50 | 3.77 | 4.80 | 5.76 |

| F-test | * | * | ** | ** | ns | ns | * | ** |

| C.V. (%) | 23.77 | 12.72 | 13.85 | 13.65 | 23.21 | 18.47 | 16.14 | 13.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khamnonin, W.; Wongsa, T.; Ponsen, M.; Sanitchon, J.; Chankaew, S.; Monkham, T. Hydroponic and Soil-Based Screening for Salt Tolerance and Yield Potential in the Different Growth Stages of Thai Indigenous Lowland Rice Germplasm. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112574

Khamnonin W, Wongsa T, Ponsen M, Sanitchon J, Chankaew S, Monkham T. Hydroponic and Soil-Based Screening for Salt Tolerance and Yield Potential in the Different Growth Stages of Thai Indigenous Lowland Rice Germplasm. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112574

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhamnonin, Wilai, Tanawat Wongsa, Monchita Ponsen, Jirawat Sanitchon, Sompong Chankaew, and Tidarat Monkham. 2025. "Hydroponic and Soil-Based Screening for Salt Tolerance and Yield Potential in the Different Growth Stages of Thai Indigenous Lowland Rice Germplasm" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112574

APA StyleKhamnonin, W., Wongsa, T., Ponsen, M., Sanitchon, J., Chankaew, S., & Monkham, T. (2025). Hydroponic and Soil-Based Screening for Salt Tolerance and Yield Potential in the Different Growth Stages of Thai Indigenous Lowland Rice Germplasm. Agronomy, 15(11), 2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112574