Agronomic Potential and Limitations of Factory-Derived Tea Waste in Kale Cultivation Under Drought Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Tea Waste and Soil Characteristics

2.3. Seedling Production

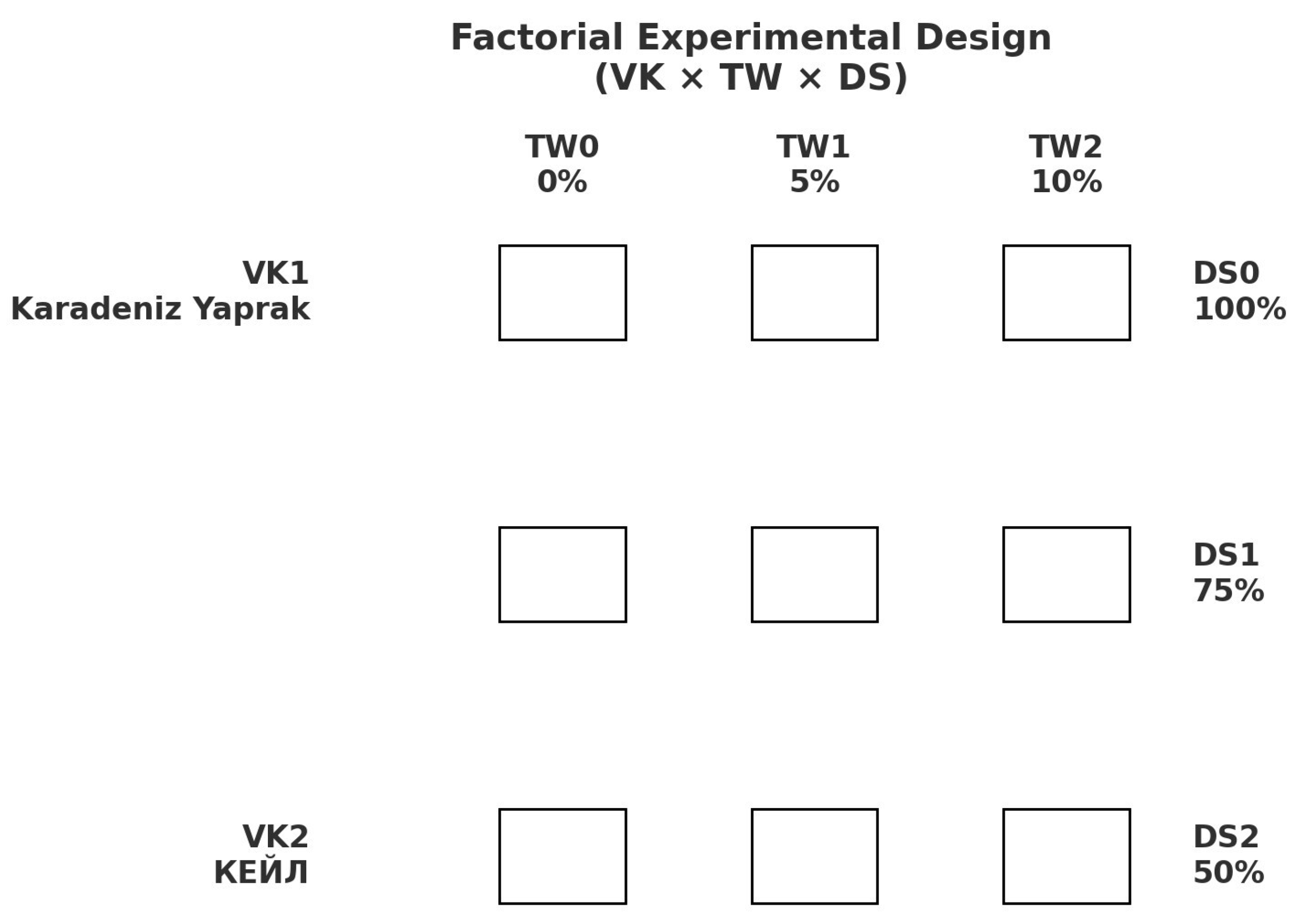

2.4. Pot Experiment and Drought Stress Application

2.5. Observations and Measurements

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Growth and Biomass

3.2. Water Status and Pigments

3.3. Root System Traits

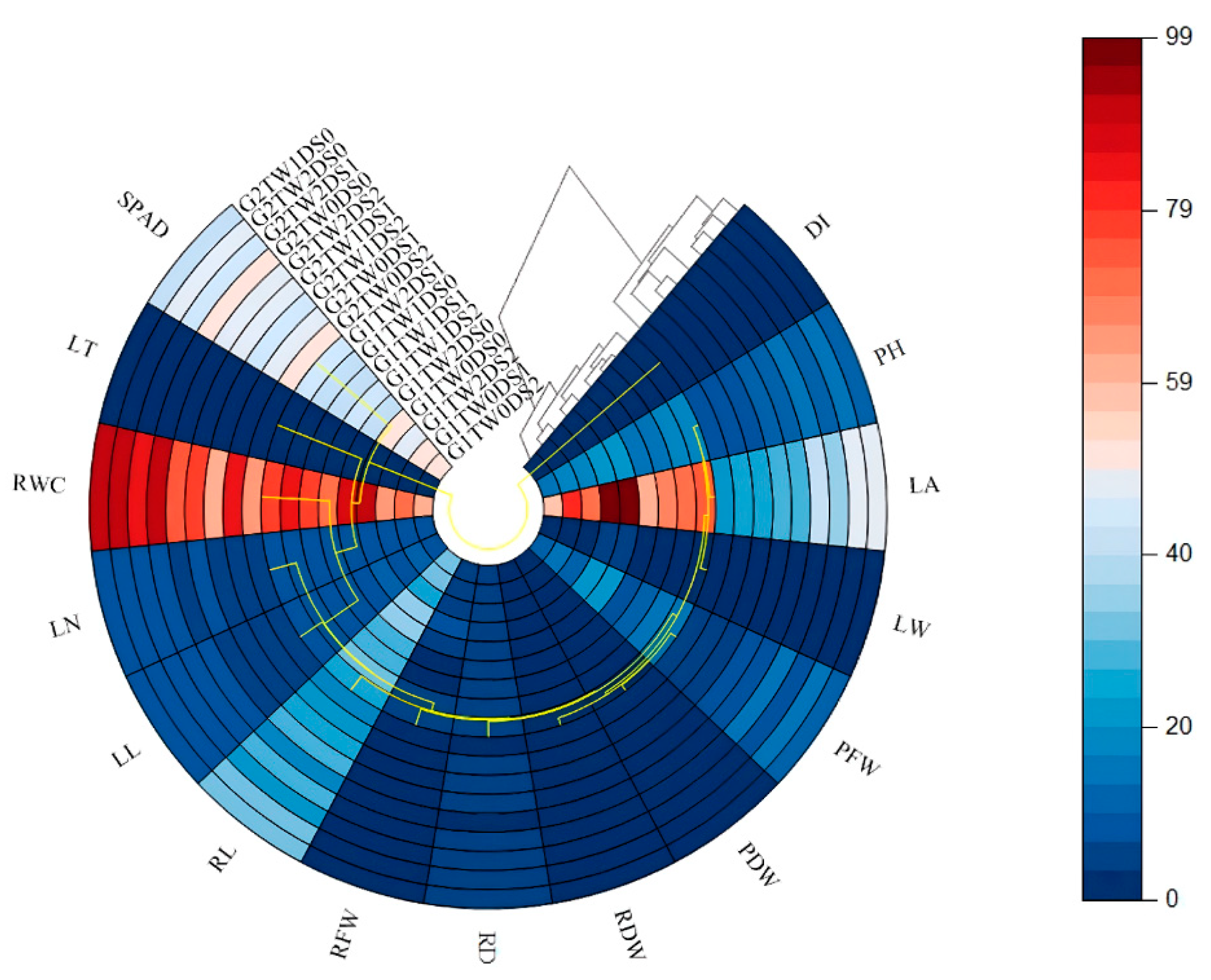

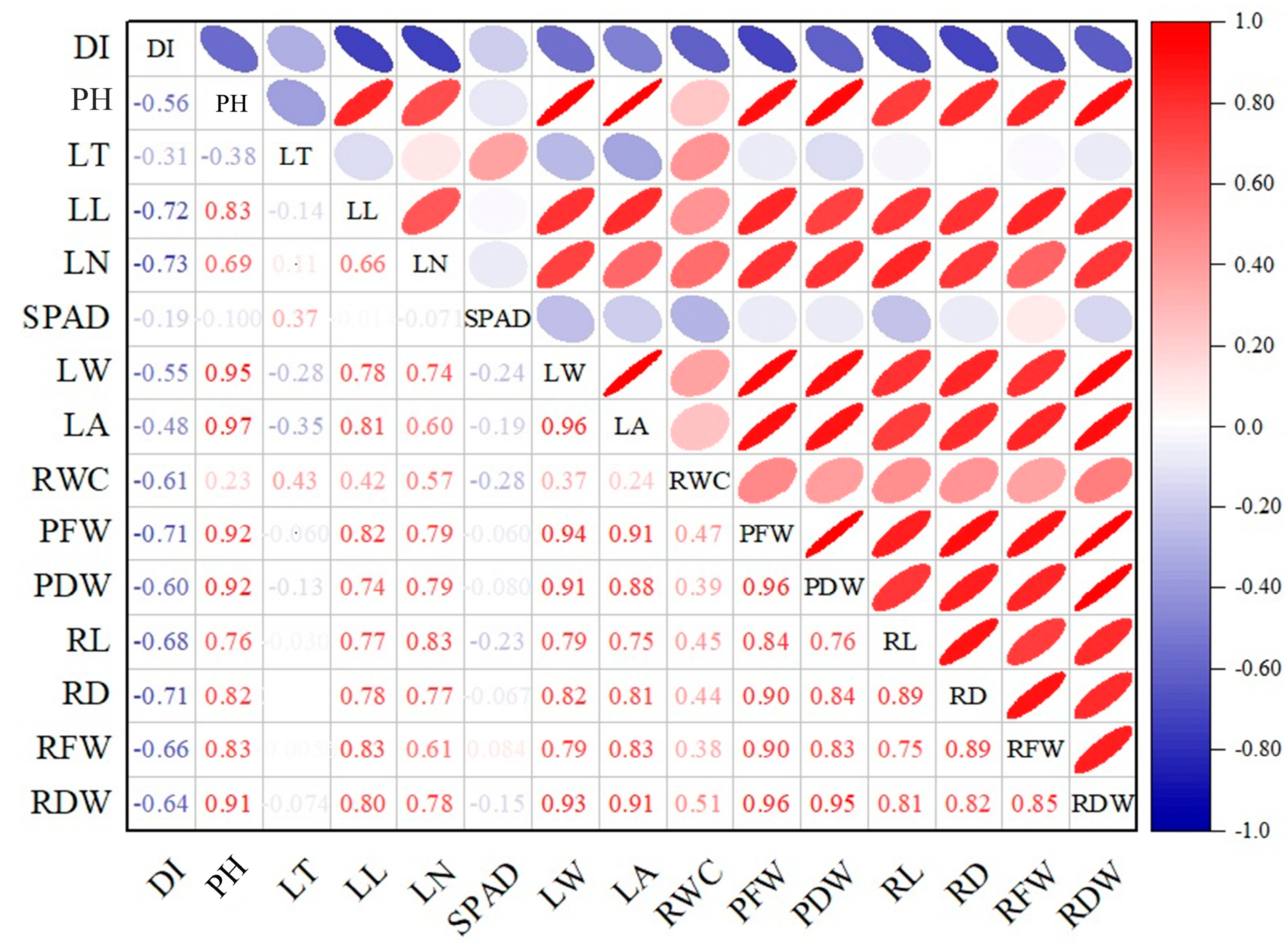

3.4. Multivariate Patterns (PCA, Correlations)

4. Discussion

4.1. Drought Stress Effects on Kale Growth and Biomass

4.2. Interaction Effects of Drought Stress and Tea Waste Amendment

4.3. Physiological and Biochemical Responses Under Drought and Tea Waste Amendment

4.4. Trait Interrelationships Revealed by PCA and Correlation Heatmap

4.5. Role of Organic Amendments in Mitigating Drought Stress

4.6. Composition and Variability of Tea Waste

4.7. Valorization Potential of Tea Waste

4.8. Comparative Stress Physiology with Other Crops

4.9. Agronomic Potential and Limitations of Tea Waste Under Drought Stress

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Šamec, D.; Urlić, B.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) as a superfood: Review of the scientific evidence behind the statement. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2019, 59, 2411–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkaya, A.; Yanmaz, R. Promising kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) populations from Black Sea region, Turkey. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2005, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, C.; Howard, N.P.; Albach, D.C. Different shades of kale—Approaches to analyze kale variety interrelations. Genes 2022, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferioli, F.; Manco, M.; Giambanelli, E.; D’Antuono, L.F.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Sanches-Silva, A.; Koçaoğlu, B.; Hayran, O. Variability of glucosinolates and phenolics in local kale populations from Turkey, Italy and Portugal. In Proceedings of the 9th International Food Data Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 September 2011; Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge, IP: Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Satheesh, N.; Workneh Fanta, S. Kale: Review on nutritional composition, bioactive compounds, antinutritional factors, health-beneficial properties and value-added products. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1811048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartea, M.E.; Picoaga, A.; Soengas, P.; Ordás, A. Morphological characterization of kale populations from northwestern Spain. Euphytica 2003, 129, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipan, B.; Neji, M.; Meglič, V.; Sinkovič, L. Genetic diversity of kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) using agro-morphological and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 71, 1221–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Hernández, E.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Improving the health-benefits of kales (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala DC) through the application of controlled abiotic stresses: A Review. Plants 2021, 10, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagüzel, Ü.Ö. Blossoms amid drought: A bibliometric mapping of research on drought stress in ornamental plants (1995–2025). Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1644092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirana, I.; Thavarajah, P.; Siva, N.; Wickramasinghe, A.N.; Smith, P. Moisture deficit effects on kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) biomass, mineral, and low molecular weight carbohydrate concentrations. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 226, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, N.; Tkalec, M.; Major, N.; Vasari, A.T.; Tokić, M.; Vitko, S.; Ban, D.; Ban, S.G.; Salopek-Sondi, B. Mechanisms of kale (Brassica oleracea var. acephala) tolerance to individual and combined stresses of drought and elevated temperature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Miao, H.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B.; Wang, Q. Seasonal variation in nutritional substances in varieties of leafy Chinese kale (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra): A pilot trial. Agronomy 2025, 15, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issarakraisila, M.; Ma, Q.; Turner, D.W. Photosynthetic and growth responses of juvenile Chinese kale (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra) and caisin (Brassica rapa subsp. parachinensis) to waterlogging and water deficit. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 111, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barickman, T.C.; Ku, K.M.; Sams, C.E. Differing precision irrigation thresholds for kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) induce changes in physiological performance, metabolites, and yield. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 180, 104253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.; Fischer, S.; Lambert, C.; Hilger, T.; Jordan, I.; Cadisch, G. Combined effects of drought and soil fertility on the synthesis of vitamins in green leafy vegetables. Agriculture 2023, 13, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, K.; Li, J.; Gong, B.; Lu, Y.; Wu, X.; Lü, G.; Gao, H. Drought Stress Tolerance in Vegetables: The Functional Role of Structural Features, Key Gene Pathways, and Exogenous Hormones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.R.; MacDonald, M.T.; Abbey, L. Impact of Water Deficit Stress on Brassica Crops: Growth and Yield, Physiological and Biochemical Responses. Plants 2025, 14, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1513–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Caretta, M.A.; Mukherji, A.; Arfanuzzaman, M.; Betts, R.A.; Gelfan, A.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Lissner, T.K.; Liu, J.; Lopez Gunn, E.; Morgan, R.; et al. Water. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 551–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bot, A.; Benites, J. The Importance of Soil Organic Matter: Key to Drought-Resistant Soil and Sustained Food Production; FAO Soils Bulletin 80; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hueso, S.; Hernández, T.; García, C. Resistance and resilience of the soil microbial biomass to severe drought in semiarid soils: The importance of organic amendments. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2011, 50, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J. Water infiltration and soil structure related to organic matter and its stratification with depth. Soil. Tillage Res. 2002, 66, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, R.J.; Cotrufo, M.F. The ability of soils to aggregate, more than the state of aggregation, promotes protected soil organic matter formation. Geoderma 2024, 442, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Martínez-Zapata, A.; Navarro, S. Valorization of agro-industrial wastes as organic amendments to reduce herbicide leaching into soil. J. Xenobiotics. 2025, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Jilani, G.; Arshad, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Khalid, A. Bio-conversion of organic wastes for their recycling in agriculture: An overview of perspectives and prospects. Ann. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiranmai, R.Y.; Neeraj, A.; Vats, P. Improvement of soil health and crop production through utilization of organic wastes: A sustainable approach. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2024, 13, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Iqbal, R.; Deng, G. Biochar from agricultural waste as a strategic resource for promotion of crop growth and nutrient cycling of soil under drought and salinity stress conditions: A comprehensive review with context of climate change. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1832–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Haldar, D.; Purkait, M.K. Potential and sustainable utilization of tea waste: A review on present status and future trends. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, T.G.; Saricaoglu, B.; Ozkan, G.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Valorization of tea waste: Composition, bioactivity, extraction methods, and utilization. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3112–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunklová, B.; Jeníček, L.; Malaťák, J.; Neškudla, M.; Velebil, J.; Hnilička, F. Properties of biochar derived from tea waste as an alternative fuel and its effect on phytotoxicity of seed germination for soil applications. Materials 2022, 15, 8709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karataş, A. Is tea waste a promising co-substrate for optimizing the cultivation, growth, and yield of Charleston pepper (Capsicum annuum L.)? Res. Agric. Sci. 2024, 55, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, G.H.; Ay, E.B.; Şahin, M.D. The effects of tea wastes prepared using different composting methods on the seedling growth and selected biochemical properties of maize (Zea mays var. indurata). Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekbiç, E.; Keskin, A. Effects of tea waste compost applications on onion grown under salt stress conditions. Akademik Ziraat Dergisi 2018, 7, 1–8. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özenç, D.B.; Hut, D. Effects of tea waste compost and salt applications on the growth of pepper plants. Topr. Bil. Bitki Besl. Derg. 2018, 6, 86–94. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kıran, S.; Baysal Furtana, G. Responses of eggplant seedlings to combined effects of drought and salinity stress: Effects on photosynthetic pigments and enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıran, S.; Kuşvuran, Ş.; Özkay, F.; Ellialtıoğlu, Ş. The change of some morphological parameters in salt tolerant and salt sensitive eggplant genotypes under drought stress condition. MKUJAS 2016, 21, 130–138. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Kuşvuran, Ş.; Daşgan, H.Y.; Abak, K. Responses of different melon genotypes to drought stress. Yüzüncü Yil Üniversitesi J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 21, 209–219. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Smart, R.E.; Bingham, G.E. Rapid estimates of relative water content. Plant Physiol. 1974, 53, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ammar, H.; Picchi, V.; Arena, D.; Treccarichi, S.; Bianchi, G.; Lo Scalzo, R.; Branca, F. Variation of bio-morphometric traits and antioxidant compounds of Brassica oleracea L. accessions in relation to drought stress. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeltaif, S.A.; SirElkhatim, K.A.; Hassan, A.B. Estimation of phenolic and flavonoid compounds and antioxidant activity of spent coffee and black tea (processing) waste for potential recovery and reuse in Sudan. Recycling 2018, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiah, N.I.; Uthumporn, U. Determination of phenolic and antioxidant properties in tea and spent tea under various extraction methods and determination of catechins, caffeine, and gallic acid by HPLC. IJASEIT 2015, 11, 10–18517. [Google Scholar]

- Ekbiç, H.B.; Akbulut, Ş.; Özenç, D.B. Effects of mixtures of hazelnut husk and tea waste compost on the development of 41B American grapevine rootstock cuttings grown under saline conditions. Akademik Ziraat Dergisi 2022, 11, 1–8. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Mohi-Ud-Din, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Rohman, M.M.; Uddin, M.N.; Haque, M.S.; Ahmed, J.U.; Hossain, A.; Hassan, M.M.; Mostofa, M.G. Multivariate analysis of morpho-physiological traits reveals differential drought tolerance potential of bread wheat genotypes at the seedling stage. Plants 2021, 10, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevilly, S.; Dolz-Edo, L.; López-Nicolás, J.M.; Morcillo, L.; Vilagrosa, A.; Yenush, L.; Mulet, J.M. Physiological and molecular characterization of the differential response of broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) cultivars reveals limiting factors for broccoli tolerance to drought stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 10394–10404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, M.J.; Hwang, Y.; Koh, Y.M.; Zhu, F.; Deshpande, A.S.; Bechard, T.; Andreescu, S. Physiological and molecular modulations to drought stress in the Brassica species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M. Impact of biochar in mitigating the negative effect of drought stress on cabbage seedlings. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 2297–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.G.; Choi, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, D.G.; Yun, Y.U. Response of biochar amendment for substituting organic fertilizer ingredients in kale-grown soils. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 51, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepsilvisut, O.; Srikan, N.; Chutimanukul, P.; Athinuwat, D.; Chuaboon, W.; Marubodee, R.; Ehara, H. Practical guidelines for farm waste utilization in sustainable kale production. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, R.; Almela, C.; Bernal, M.P. A remediation strategy based on active phytoremediation followed by natural attenuation in a soil contaminated by pyrite waste. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 143, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780123849052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güçlü Üstündağ, Ö.; Erşan, S.; Özcan, E.; Özan, G.; Kayra, N.; Ekinci, F.Y. Black tea processing waste as a source of antioxidant and antimicrobial phenolic compounds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, E. Comparative evaluation of eggplant genotypes with their wild relatives under gradually increased drought stress. Bragantia 2024, 83, e20230246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kıran, S.; Baysal Furtana, G.; Ellialtıoğlu, Ş.Ş. Physiological and biochemical assay of drought stress responses in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) inoculated with commercial inoculant of Azotobacter chroococcum and Azotobacter vinelandii. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 305, 111394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 5.57 |

| EC (dS m−1) | 0.102 |

| Total N (%) | 2.19 |

| P (ppm) | 395.6 |

| K (ppm) | 5792 |

| Organic matter (%) | 47 |

| Water holding capacity (%) | 96.02 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Texture class | Clayey |

| EC (dS m−1, saturated paste) | 0.62 |

| pH (saturated paste) | 6.93 |

| CaCO3 (%) | 1.80 |

| Total N (%) | 0.09 |

| P (ppm) | 4.18 |

| K (ppm) | 31.7 |

| Organic matter (%) | 2.58 |

| Variety (VK) | Tea Waste (TW, %) | Irrigation Regime (RI) |

|---|---|---|

| Karadeniz Yaprak (VK1) | 0 (TW0) | DS0: Control (100% field capacity) DS1: Light stress (75% field capacity) DS2: Moderate stress (50% field capacity) |

| 5 (TW1) | DS0: Control (100% field capacity) DS1: Light stress (75% field capacity) DS2: Moderate stress (50% field capacity) | |

| 10 (TW2) | DS0: Control (100% field capacity) DS1: Light stress (75% field capacity) DS2: Moderate stress (50% field capacity) | |

| KEЙЛ (VK2) | 0 (TW0) | DS0: Control (100% field capacity) DS1: Light stress (75% field capacity) DS2: Moderate stress (50% field capacity) |

| 5 (TW1) | DS0: Control (100% field capacity) DS1: Light stress (75% field capacity) DS2: Moderate stress (50% field capacity) | |

| 10 (TW2) | DS0: Control (100% field capacity) DS1: Light stress (75% field capacity) DS2: Moderate stress (50% field capacity) |

| Sources of Variation | df | DI | PH | LT | LL | LN | SPAD | LW | LA | RWC | PFW | PDW | RL | RD | RFW | RDW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VK | 1 | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| TW | 2 | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| DS | 2 | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| VK × TW | 2 | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| VK × DS | 2 | ** | * | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ns | ns | ** | * | ** | ns |

| TW × DS | 4 | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| VK × TW × DS | 4 | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ns | * | ** | ns | ** | ns |

| Error | 68 | 0.0026 | 0.236 | 0.0005 | 0.0243 | 0.1369 | 0.7464 | 0.0101 | 0.58 | 0.181 | 1.008 | 0.035 | 0.194 | 0.037 | 0.027 | 0.005 |

| CV (%) | 4.39 | 3.32 | 4.14 | 2.07 | 4.82 | 1.86 | 4.29 | 1.40 | 0.55 | 8.89 | 11.30 | 1.610 | 4.23 | 5.16 | 12.71 |

| Variety | TW (%) | DS | DI | PH (cm) | LT (mm) | LL (cm) | LN (Number Plant−1) | SPAD | LW (g) | LA (cm2) | RWC (%) | PDW (g Plant−1) | RL (cm) | RFW (g Plant−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VK1 | TW0 | DS0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 l | 21.67 ± 1.01 a | 0.200 ± 0.01 b | 12.44 ± 0.26 a | 8.60 ± 0.12 bc | 50.30 ± 0.48 bc | 3.62 ± 0.08 b | 98.6 ± 0.90 a | 92.36 ± 0.32 a | 2.84 ± 0.18 a | 35.36 ± 0.46 a | 7.64 ± 0.29 a |

| DS1 | 0.34 ± 0.05 k | 18.98 ± 0.39 c | 0.188 ± 0.01 cd | 10.20 ± 0.23 b | 8.04 ± 0.36 def | 50.36 ± 0.69 bc | 3.18 ± 0.13 c | 81.80 ± 1.55 b | 71.54 ± 0.40 j | 2.06 ± 0.32 cd | 31.28 ± 0.41 b | 3.90 ± 0.21 cd | ||

| DS2 | 1.10 ± 0.10 h | 16.48 ± 0.48 e | 0.176 ± 0.01 e | 8.08 ± 0.08 d | 8.38 ± 0.29 bcd | 52.60 ± 0.63 a | 2.60 ± 0.07 e | 58.88 ± 0.48 g | 60.22 ± 0.27 o | 1.80 ± 0.16 ef | 29.72 ± 0.54 e | 3.76 ± 0.15 d | ||

| TW1 | DS0 | 0.72 ± 0.04 i | 17.90 ± 0.22 d | 0.140 ± 0.01 j | 9.10 ± 0.10 c | 7.78 ± 0.22 efgh | 40.04 ± 1.05 h | 3.04 ± 0.11 d | 70.56 ± 0.34 d | 84.41 ± 0.27 e | 1.84 ± 0.18 def | 30.50 ± 0.43 cd | 3.46 ± 0.09 e | |

| DS1 | 1.46 ± 0.05 e | 15.86 ± 0.68 f | 0.142 ± 0.01 ij | 7.52 ± 0.08 e | 7.60 ± 0.20 fgh | 40.78 ± 0.72 h | 2.68 ± 0.08 e | 66.74 ± 0.87 e | 77.57 ± 0.14 h | 1.54 ± 0.05 gh | 28.70 ± 0.63 f | 2.86 ± 0.18 g | ||

| DS2 | 1.74 ± 0.05 c | 15.22 ± 0.34 g | 0.156 ± 0.01 gh | 7.26 ± 0.05 f | 7.02 ± 0.08 i | 43.00 ± 0.83 fg | 2.20 ± 0.12 g | 61.28 ± 0.88 f | 70.46 ± 0.38 k | 1.18 ± 0.15 ij | 26.90 ± 0.29 g | 2.50 ± 0.12 h | ||

| TW2 | DS0 | 1.04 ± 0.05 h | 19.90 ± 0.31 b | 0.198 ± 0.01 b | 7.92 ± 0.08 d | 8.80 ± 0.25 b | 42.32 ± 1.19 g | 4.18 ± 0.13 a | 97.66 ± 0.63 a | 86.52 ± 0.34 d | 2.98 ± 0.26 a | 35.78 ± 0.30 a | 4.88 ± 0.39 b | |

| DS1 | 1.36 ± 0.05 fg | 18.54 ± 0.40 c | 0.160 ± 0.01 fg | 7.52 ± 0.08 e | 8.04 ± 0.58 def | 42.96 ± 1.09 fg | 3.10 ± 0.10 cd | 73.64 ± 0.76 c | 78.56 ± 0.36 g | 2.58 ± 0.13 b | 25.28 ± 0.24 h | 4.00 ± 0.10 c | ||

| DS2 | 1.74 ± 0.05 c | 17.62 ± 0.33 d | 0.150 ± 0.01 hi | 7.08 ± 0.08 fg | 7.54 ± 0.18 gh | 49.30 ± 0.71 cd | 2.98 ± 0.08 d | 70.10 ± 0.65 d | 65.33 ± 0.36 l | 2.00 ± 0.16 cde | 24.58 ± 0.22 i | 3.38 ± 0.13 e | ||

| VK2 | TW0 | DS0 | 0.00 ± 0.00 l | 13.64 ± 0.56 h | 0.224 ± 0.01 a | 6.94 ± 0.09 g | 8.58 ± 0.10 bc | 50.42 ± 1.39 b | 2.38 ± 0.08 f | 42.40 ± 0.76 j | 91.78 ± 0.60 b | 1.66 ± 0.27 fg | 27.44 ± 0.42 g | 3.14 ± 0.05 f |

| DS1 | 1.42 ± 0.04 ef | 8.80 ± 0.42 l | 0.220 ± 0.01 a | 5.28 ± 0.19 j | 6.24 ± 0.19 kj | 49.06 ± 0.90 d | 1.02 ± 0.13 k | 23.96 ± 0.50 n | 82.74 ± 0.56 f | 0.70 ± 0.12 lm | 21.50 ± 0.57 k | 2.36 ± 0.11 h | ||

| DS2 | 1.96 ± 0.05 a | 8.62 ± 0.46 l | 0.200 ± 0.01 b | 4.56 ± 0.09 k | 5.82 ± 0.18 k | 50.54 ± 0.61 b | 0.80 ± 0.10 l | 22.08 ± 0.59 o | 63.30 ± 0.35 m | 0.60 ± 0.10 m | 17.16 ± 0.47 m | 1.98 ± 0.13 i | ||

| TW1 | DS0 | 1.34 ± 0.05 g | 12.12 ± 0.19 i | 0.204 ± 0.01 b | 8.04 ± 0.11 d | 8.24 ± 0.18 cde | 39.90 ± 1.01 h | 2.64 ± 0.05 e | 48.92 ± 0.73 h | 90.11 ± 0.49 c | 1.28 ± 0.16 i | 30.30 ± 0.51 d | 3.14 ± 0.05 f | |

| DS1 | 1.44 ± 0.05 e | 11.62 ± 0.38 i | 0.196 ± 0.01 bc | 6.34 ± 0.34 i | 8.00 ± 0.27 defg | 49.04 ± 0.58 d | 1.28 ± 0.08 j | 27.78 ± 0.54 m | 78.01 ± 0.42 h | 1.32 ± 0.15 hi | 28.48 ± 0.42 f | 2.40 ± 0.07 h | ||

| DS2 | 1.64 ± 0.05 d | 9.52 ± 0.29 k | 0.186 ± 0.01 d | 5.16 ± 0.05 j | 6.42 ± 0.30 j | 43.60 ± 0.79 f | 1.02 ± 0.13 k | 25.52 ± 0.53 n | 61.96 ± 0.61 n | 0.92 ± 0.08 kl | 25.64 ± 0.49 h | 1.98 ± 0.13 i | ||

| TW2 | DS0 | 0.48 ± 0.04 j | 15.24 ± 0.69 g | 0.204 ± 0.01 b | 8.10 ± 0.10 d | 9.42 ± 0.27 a | 46.20 ± 0.86 e | 2.42 ± 0.08 f | 46.72 ± 0.80 i | 90.56 ± 0.46 c | 2.16 ± 0.25 c | 30.86 ± 0.65 bc | 3.08 ± 0.13 f | |

| DS1 | 1.44 ± 0.05 e | 11.52 ± 0.41 i | 0.220 ± 0.01 a | 6.94 ± 0.09 g | 7.36 ± 0.18 hi | 45.50 ± 0.68 e | 1.66 ± 0.05 h | 35.98 ± 0.37 k | 84.83 ± 0.44 e | 1.30 ± 0.20 i | 22.68 ± 0.40 j | 1.66 ± 0.09 j | ||

| DS2 | 1.86 ± 0.05 b | 10.46 ± 0.67 j | 0.168 ± 0.01 ef | 6.62 ± 0.26 h | 6.42 ± 0.30 j | 48.70 ± 0.78 d | 1.42 ± 0.08 i | 29.26 ± 0.83 l | 72.85 ± 0.55 i | 1.00 ± 0.16 jk | 19.58 ± 0.29 l | 1.36 ± 0.09 k | ||

| LSD %5 | 0.065 | 0.614 | 0.023 | 0.197 | 0.467 | 1.090 | 0.127 | 0.959 | 0.537 | 0.236 | 0.555 | 0.208 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oğuz, A.; Boyacı, H.F. Agronomic Potential and Limitations of Factory-Derived Tea Waste in Kale Cultivation Under Drought Stress. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112478

Oğuz A, Boyacı HF. Agronomic Potential and Limitations of Factory-Derived Tea Waste in Kale Cultivation Under Drought Stress. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112478

Chicago/Turabian StyleOğuz, Alparslan, and Hatice Filiz Boyacı. 2025. "Agronomic Potential and Limitations of Factory-Derived Tea Waste in Kale Cultivation Under Drought Stress" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112478

APA StyleOğuz, A., & Boyacı, H. F. (2025). Agronomic Potential and Limitations of Factory-Derived Tea Waste in Kale Cultivation Under Drought Stress. Agronomy, 15(11), 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112478