Abstract

The increasing demand for sustainable agriculture has accelerated research into eco-friendly plant health management, particularly through natural substances rich in bioactive compounds. In this study, various substances, including essential oils, extracts from Aloe vera, artichoke and ornamental plants, by-products from beer and coffee processing, and selected commercial formulations including biostimulants and a plant strengthener, were evaluated for their antimicrobial properties and ability to trigger plant defenses. Notably, Agapanthus spp. exhibited strong antifungal activity against the fungus Botrytis cinerea (Bc), while thyme, tea tree, and lavender essential oils were effective against both Bc and the bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst). Greenhouse trials on tomato plants demonstrated the protective effects of A. vera gel and ornamental plant extracts against Bc and Potato virus Y (PVY), while coffee and artichoke extracts were effective against Pst. An alginate-based formulation containing thyme oil showed enhanced in planta efficacy against the three pathogens. Gene expression analyses revealed early upregulation of PR-1 and PR-4, especially with alginate treatments and A. vera gel at 12 h post-treatment (hpt) while coffee extract triggered the strongest late response at 72 hpt. These findings highlight the potential of plant-derived substances in promoting sustainable plant disease management through both direct antimicrobial action and immune system activation.

1. Introduction

Agriculture is at the nexus of some of the most pressing global challenges, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and soil degradation. As both a driver of and a sector impacted by environmental change, it must shift toward more sustainable and resilient practices [1,2]. In this context, sustainable agriculture has emerged as a holistic framework aimed at maintaining agricultural productivity while conserving natural resources, supporting rural livelihoods, and minimizing environmental impact. It integrates ecological principles with farming practices to ensure long-term food security and agroecosystem health [2,3]. Its foundational principles include reducing chemical input, enhancing biodiversity, improving soil health, and promoting eco-friendly pest and disease management strategies. The need for such practices is further reinforced by the increasing frequency and intensity of biotic and abiotic stressors, which are responsible for up to 20–30% in global yield losses annually [4] and are further exacerbated by climate change [5,6,7].

As a sustainable alternative, to overcome these challenges without compromising food security, plant-derived natural extracts—such as essential oils (EOs), botanical formulations, and microbial metabolites—are gaining attention for their multifunctionality and safety [8]. Rich in diverse bioactive compounds like alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, and flavonoids, plant extracts offer both direct antimicrobial action and the ability to trigger plant defense responses. Certain secondary metabolites have demonstrated strong antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral properties, providing both preventive and curative benefits against phytopathogens [9]. Aligned with global sustainability initiatives—such as the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy, which targets a 50% reduction in chemical pesticide use by 2030 [10]—these natural products present a viable path toward integrated pest management. Their generally minimal toxicity to humans and the environment, combined with their capacity to enhance crop resilience and maintain yield quality, underscores their potential in sustainable agriculture. Beyond their direct antimicrobial roles, many plant-based extracts function as natural elicitors that stimulate the plant’s internal defense mechanisms. Plants possess complex immune systems that can be activated through induced resistance pathways. Two key types of induced resistance—Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) and Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR)—involve complex signaling networks often activated by natural elicitors or beneficial microorganisms [11,12,13]. These pathways lead to the induced expression of pathogenesis-related genes, such as PR-1 and PR-4 (common markers for the salicylic acid (SA)- and ethylene/jasmonic acid (ET/JA) pathways, respectively), the production of antimicrobial secondary metabolites, contributing to durable and broad-spectrum resistance.

Natural elicitors and resistance inducers have become promising alternatives to synthetic inputs, capable of activating plant defenses with reduced environmental impact [14,15]. These agents can trigger plant defense responses; however, their effectiveness varies and requires optimization under field conditions. Further research is required to improve their integration into crop protection strategies at the field level.

This research investigates the potential of natural substances as safer, bio-based alternatives for crop protection, focusing on their direct antimicrobial activity and ability to induce resistance in plants. Using tomato as a model system, the study assesses the efficacy of various natural extracts against three economically significant pathogens: the fungus Botrytis cinerea (Bc), the causal agent of gray mold, a widespread disease affecting numerous horticultural crops, and the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato (Pst), causing bacterial speck disease on tomato, and necrogenic strains of potato virus Y (PVYC-to), responsible for mosaic and leaf necrosis symptoms on potato and tomato. Through in vitro and in vivo assays, including efficacy tests and gene expression analyses, this study explores the potential of plant-derived and agro-industrial products as effective and environmentally safe alternatives for plant health management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Culture Media

Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) was prepared by infusing 200 g of peeled and sliced potatoes in water at 60 °C for 1 h, followed by the addition of 20 g D-(+)-glucose and adjustment of the pH to 6.5. Then 20 g of bacteriological agar (LLG Labware, Meckenheim, Germany) was added per liter of distilled water. Nutrient Sucrose Agar (NSA) was prepared by combining 50 g of sucrose, 8 g of nutrient broth, and 20 g of bacteriological agar (LLG Labware) per liter of distilled water. Luria–Bertani (LB) broth was prepared by dissolving 10 g of tryptone peptone (Difco™, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 5 g of yeast extract (Difco™), 10 g of NaCl, and 15 g of bacto-agar (Difco™) per liter of distilled water.

2.2. Fungal, Bacterial and Viral Strains and Culture Conditions

B. cinerea strain SAS56, P. syringae pv. tomato strain PST46, and potato virus Y strain PVYC-to, used in this study, were retrieved from well-characterized microbial and viral stock collections maintained within the DiSSPA-UNIBA laboratories. Fungal and bacterial cultures were stored in aqueous 10% glycerol at −80 °C and revitalized immediately prior to use. PVYC-to was maintained and propagated in plants of Solanum lycopersicum cv. UC82, highly susceptible to PVYC-to infection, grown under controlled conditions at 24 ± 2 °C with a 16-h photoperiod [16].

Bc was cultured on PDA, incubated at 21 ± 1 °C in darkness for 2 days, and subsequently exposed to a 12-h daily photoperiod under a combination of natural daylight and near-UV light for 7 days to induce sporulation. Conidia were collected in sterile distilled water containing Tween 20%, filtered through Miracloth Calbiochem® (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) to remove hyphal fragments, and adjusted to a final concentration of 1 × 105 conidia mL−1.

Pst was cultured on NSA and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C for 24–48 h. Individual colonies were used to inoculate LB broth and incubated overnight with shaking at 250 rpm. For plant inoculation, overnight bacterial cultures were centrifuged, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in sterile water to a final concentration of 2 × 108 cells mL−1. For in vitro assays, overnight cultures (200 µL) were inoculated in 5 mL of fresh LB broth and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C until reaching an optical density of 0.11, measured spectrophotometrically at 550 nm, corresponding to a concentration of 1 × 108 cells mL−1.

2.3. Plant Extracts and Other Natural Compounds

A total of 38 plant-based extracts and natural compounds were evaluated for their antimicrobial activity and ability to induce resistance in tomato plants. These included extracts derived from Aloe vera, ornamental species, spent coffee grounds, artichoke and beer by-products, essential oils (EOs), alginate-based formulations, and various commercial biostimulants and plant activators (Table 1). Detailed preparation methods are provided in Supplementary File S1. Briefly, three distinct A. vera preparations were used: a gel extract in sterile distilled water [17,18]; a polysaccharide-rich extract [19]; and a powdered leaf extract [20]. Spent coffee grounds (Coffea arabica L.; 80% Arabica and 20% Robusta) were extracted at 4% using three aqueous methods: infusion, boiling, and room temperature incubation [21]. Extracts from ornamental plants were prepared by homogenizing surface-sterilized leaves in sterile distilled water at 2.5% (w/v). Various artichoke by-product extracts were tested: A1 and A2 were water extracts; A3 was a super-critical CO2 extract in 30% co-solvent ethanol (EtOH) [21]; A4 and A5 were methanolic (MeOH) extracts in 50% of solvent [22]. Beer by-products from a local craft brewery were used as either centrifuged (BEER-C) or non-centrifuged (BEER-NC) extracts. Essential oils, obtained by steam distillation and provided by Hekomia (Ostuni, BR, Italy) or LaborBIO (Collegno, TO, Italy), were tested undiluted in vitro. Thyme EO was applied in vivo either directly or encapsulated in 1.8 mm alginate microbeads, with empty microbeads serving as controls [23]. Commercial formulations included biostimulants and fertilizers, as well as a wood extract-based plant strengthener. The synthetic inducer of systemic acquired resistance (SAR), acibenzolar-S-methyl (BION® 50 WG; Syngenta Crop Protection, Basel, Switzerland), was used as a reference chemical control. These products were applied in vivo at label-recommended concentrations. For in vitro assays, products were used either directly (as received) for diffusion tests or applied at 1% and 10% (v/v) of the prepared label dose solution. All extracts were evaluated in both in vitro and in vivo assays, with their concentrations and key details summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Natural compounds and plant extracts used in in vitro and in planta assays.

2.4. In Vitro Antimicrobial Assays

The antimicrobial activity of plant extracts and natural compounds against Bc and Pst was assessed through in vitro assays using the disk diffusion method (Kirby–Bauer antibiotic testing), as described by EUCAST (2020). Briefly, 100 µL aliquots of fungal (1 × 105 conidia mL−1) or bacterial (1 × 108 cells mL−1) suspensions were uniformly spread onto the surface of 90 mm Petri dishes containing PDA or NSA, respectively. Sterile antimicrobial susceptibility test disks of 6 mm diameter (Oxoid, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basingstoke, UK) were impregnated with 20 µL of each test compound and aseptically placed onto the inoculated agar surface (five disks per plate). The plates were incubated in darkness at 21 ± 1 °C or 25 ± 1 °C, respectively. The diameter of the inhibition zones was measured daily, starting from two to seven days post-inoculation (dpi). All treatments were conducted in triplicate.

In addition, Bc was subjected to further in vitro testing to assess the inhibitory activity of the extracts on colony growth and conidial germination.

For the conidial germination test, the compounds were incorporated directly into the sterilized medium. Disks (6 mm diameter) were cut from PDA plates using a sterile cork borer, placed on microscope slides, and surface inoculated with 10 µL of conidial suspension containing 1 × 105 conidia mL−1. Slides were then incubated in a humid chamber at 21 ± 1 °C for 16–24 h. Germination was evaluated microscopically (200× magnification) by observing three randomly selected groups of 100 conidia each. The percentage of germinated conidia with morphologically normal germ tubes was recorded. The germination frequency in the treated medium was compared with that in the control (extract-unamended) medium to estimate the inhibitory activity of each compound.

For the colony growth assays, PDA plates (90 mm diameter) either unamended or amended with a 10% of extract concentration were inoculated with 4 mm mycelial plugs excised from the margins of actively growing 7–10-day-old colonies. Each treatment was replicated three times. Colony diameters were daily measured in two orthogonal directions after 2–8 days of incubation at 21 ± 1 °C in darkness. The percentage of mycelial growth inhibition (MGI) was calculated using the formula:

where Dc and Dt are the mean diameters of the colonies in the control (unamended) and treated (amended) media, respectively.

MGI (%) = [(Dc − Dt)/Dc] × 100

In parallel, Bc was exposed to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by thyme EO, thyme-alginate capsules, and alginate-only capsules using a non-vented VOC chamber system, as described by Álvarez-García et al. [24] with slight modification. Briefly, the setup allowed VOC diffusion without direct contact between the EO sources and the fungal culture. The chamber consisted of a Petri dish containing the inoculated medium as the lower plate, while the lid was replaced with a modified lid from another Petri dish featuring five evenly spaced holes of 2 cm diameter. This second dish was inverted and placed on top, forming the upper part of the chamber. In this configuration, the EO or capsule treatments were positioned above the fungal culture, with the perforated lid acting as a central interface to enable VOC flow. The entire assembly was sealed with two layers of Parafilm to prevent leakage and placed in a thermostatic cabinet at 22 ± 2 °C. Control treatments included inoculated plates without EO exposure. This method was used to evaluate both fungal growth inhibition and conidial germination, based on colony diameter measurements at 2-, 3-, and 5 dpi, and germinated conidia counted at 18 h post inoculation. Each treatment was replicated three times.

2.5. In Vivo Evaluation of Effectiveness on Tomato Plants

Tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Marmande) were sown in polystyrene trays and maintained in a greenhouse at 21 ± 5 °C and 16–18 h day/night photoperiod supplemented with artificial lighting (OSRAM SubstiTUBE Value LED Tube EM T8, 20W, 2200 lm). Seedlings reaching a height of 7–10 cm were transplanted into 7 × 10 cm pots containing Brill® 3 Special substrate (Agrochimica S.p.A., Bolzano, Italy).

The experimental design followed a completely randomized scheme with five replicates per treatment. Treatments were applied once the fourth true leaves were fully expanded. Plants were sprayed with extracts formulated in liquid form at the dosage listed in Table 1. Control plants were sprayed with the same volume of sterile distilled water. Alginate microcapsules with or without thyme EO, and thyme undiluted EO (four 6 µL droplets per plant) were applied to the soil.

For the efficacy test, plants were inoculated 72–96 h post-treatment (hpt) with one of the following pathogens: Bc, Pst, or PVYC-to.

The inoculum for Pst strain PST46 was prepared at 2 × 108 CFU mL−1, and that for Bc strain SAS56 at 5 × 105 conidia mL−1 in sucrose phosphate buffer (10 mM sucrose, 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.0). Fungal and bacterial inoculation was performed by spraying both leaf surfaces with aqueous suspensions until runoff, using a hand-held nebulizer. Plants were enclosed in transparent polyethylene bags and maintained at near-saturated relative humidity by placing pot bases in shallow water to facilitate infection establishment. Post-inoculation, plant responses were monitored at 2-day intervals, depending on disease progression and pathogen type.

PVYC-to was mechanically inoculated onto apical leaves by rubbing with celite-abrasion in the presence of inoculum prepared from symptomatic leaves of tomato, homogenized in 100 mM KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.2) and kept on ice [25]. Plants were maintained at 22 ± 1 °C, and symptom development was assessed starting from 14 dpi.

Symptom assessment was conducted at specific intervals post-inoculation, depending on the pathogen: from 4 to 7 dpi for Bc, and from 7 to 14 dpi for Pst. Evaluations were performed on all leaves (6–10 per plant), using pathogen-specific empirical severity scales. For Bc, a 0–5 scale was used, based on the percentage of infected leaf surface (IFS) [0 = healthy leaf; 1 = 1–5% IFS; 2 = 6–25% IFS; 3 = 26–50% IFS; 4 = 51–75% IFS; 5 = 76–100% IFS], while a 0–7 scale was applied for Pst, [0 = healthy leaf, 1 = 1–5 small necrotic spots (SS) on the leaf, 2 = 6–10 SS, 3 = 11–15 SS; 4 = up to 25% IFS; 5 = 26–50% IFS; 6 = 51–75% IFS; 7 = 76–100% IFS]. In plants inoculated with PVYC-to, symptom assessments were carried out at 18 and 34 dpi to evaluate initial disease manifestation and potential recovery over time, using a 0–4 scale [0 = healthy plant, 1 = < 20% plant infection (PI), 2 = 20–50% PI, 3 = 51–75% PI, 4 = 76–100% PI] based on the extent of visible symptoms across the plant canopy. PI was estimated visually as the percentage of the total plant area showing virus-induced symptoms such as mosaic patterns, leaf deformation, or chlorosis. Only the most effective extracts from preliminary screenings were included in repeated trials. Disease incidence for Bc and Pst was quantified using the McKinney Index (MKI = [Σ (c × n) × 100] / N × C), where c represents the severity class, n the number of infected leaves per class, N the total number of assessed leaves, and C the maximum severity score [26]. For PVYC-to, the mean prevalence and disease severity were calculated as the arithmetic average of infection class values across the five plants per treatment.

2.6. Gene Expression Analysis

Plant responses to the treatment were studied through gene expression analysis carried out on tomato plants at 12 h and 72 h after treatment. For each treatment, 15 tomato plants were used to generate three biological replicates by collecting all leaves (4–6 leaves per plant) from five plants per replicate. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted from 100 mg of plant tissue crushed under liquid nitrogen. Subsequently, 1 mL of TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the sample in a 1.5 mL tube, centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the aqueous phase was separated. The sample was then incubated for 5 min at room temperature to improve phase separation. Chloroform (0.2 mL) was then added to the sample, and the mixture was then recentrifuged to separate the RNA into the upper aqueous phase. This was transferred to a new tube, and 0.5 mL of isopropanol was added to allow precipitation of the RNA. After washing the pellet with 1 mL of 75% ethanol, the RNA was resuspended in 50 µL of RNase-free ultrapure water.

After treatment with RQ1 RNase-free DNase I (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA) at 37 °C for 1 h, RNA was extracted with an equal volume of phenol and chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1), and once with chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1). RNA was then precipitated by adding 10 µL sodium acetate (3 M, pH 5.2), 1 µL glycogen (20 mg/mL) and 250 µL 100% EtOH. After incubation at −80 °C overnight, the sample was centrifuged at 12,000× g for 35 min at 4 °C, the pellet was air-dried and dissolved in 20 µL of RNase-free ultrapure water. Quantity and quality of RNA extracts were determined using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA integrity was assessed on a 1.2% standard agarose gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules CA, USA).

RNA extracts aliquots (0.5 μg) were then reverse transcribed by M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) using random hexanucleotide primers (50 ng/µL) and dNTPs (10 mM) in a 20 µL reaction volume and incubation at 25 °C for 10 min, and 37 °C for 50 min to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA), and heating at 70 °C for 15 min to inactivate the enzyme.

Primer pairs specific for the two target genes, PR-1 [27] and PR-4 [28], and for the reference gene, the elongation factor 1 α (EF-1) [29], were used in qPCR assays. Reaction mixture contained 1 × iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 25 μM of each forward and reverse primer, 1 μL of cDNA, and ultrapure water up to 25 μL. PCR amplification was performed using the following parameters: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, and 60 °C for 45 s for annealing and extension. Melting curve analysis was performed over the range of 60–95 °C. The relative fold change was calculated according to the 2−(ΔΔCt) method [30].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data reported are the mean values of three replicates for in vitro assays, and five replicates for the in vivo assays, from at least two independent biological experiments. Analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s test HSD (Honestly Significant Difference), was used to compare treatments using the OriginPro version 2024b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) at a p-value = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity

In vitro assays revealed antimicrobial efficacy with statistically significant differences among the tested treatments against Bc and Pst.

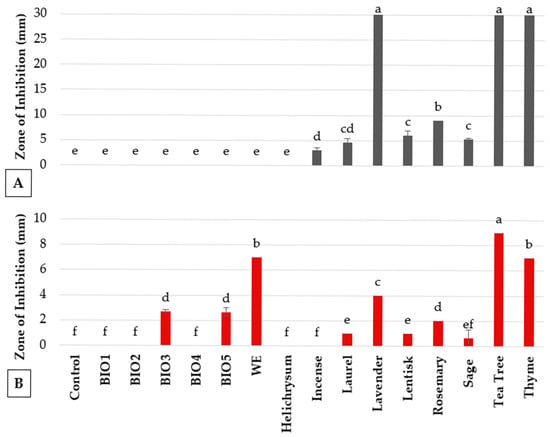

Figure 1 presents the inhibition results against these two pathogens obtained using the disk diffusion method, showing a selection of treatments that exhibited varying degrees of antimicrobial activity.

Figure 1.

In vitro antimicrobial activity of essential oils, plant biostimulants and strengthener against (A) B. cinerea and (B) P. syringae pv. tomato. Values are the mean of 3 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

Essential oils exhibited strong efficacy against Bc, with lavender, thyme, and tea tree oils producing inhibition areas of 30 mm in diameter in disk diffusion assays. Laurel, lentisk, rosemary, and sage oils showed moderate antifungal activity (3–9 mm of inhibition zone), while incense and helichrysum oils showed minimal or no activity, comparable to the untreated control (Figure 1A). Colony growth assays confirmed the antifungal effects of laurel, lavender, rosemary, thyme, and tea tree oils, all of which fully inhibited fungal growth (100%). Sage and lentisk oils provided high inhibition (84% and 74%, respectively), incense showed moderate efficacy, and helichrysum provided non-significant results (Table 2). In conidial germination assays, thyme oil was the most effective, achieving 100% inhibition. Lavender oil inhibited germination by approximately 16%, while laurel and tea tree oils showed weaker activity (5–9%). Other essential oils, including helichrysum, lentisk, rosemary, sage, and incense, showed minimal or no inhibitory effects (Table 2).

Table 2.

In vitro inhibition of B. cinerea conidial germination and colony growth by selected biostimulants, plant strengthener, plant defense activator, essential oils, and extract from ornamental plant, A. vera, coffee and artichoke extracts.

Regarding antibacterial activity, tea tree and thyme oils showed the strongest inhibition against Pst (9 mm and 7 mm inhibition areas, respectively), followed by moderate effects from lavender and rosemary essential oils (4 mm and 1 mm inhibition zones, respectively). Laurel and lentisk oils exhibited only slight inhibition, while incense and helichrysum were inactive (Figure 1B).

The biostimulants BIO1, BIO2, BIO3, BIO4, BIO5, and the wood extract exhibited strong antifungal activity against mycelial growth at 10% concentration, achieving complete inhibition. However, these treatments were ineffective at 1%, showing no significant inhibition (Table 2). Diffusion tests revealed no antimicrobial activity for these compounds (Figure 1A). Likewise, in conidial germination assays, the wood extract, BIO1, BIO4, and BIO5 at 10% completely inhibited the fungus. However, at 1%, BIO5 partially inhibited germination, and BIO4 and the wood extract had negligible effects (Table 2). BIO2 and BIO3 prevented visible germination, although interpretation was complicated by media pigmentation. The wood extract showed an inhibition area of 7 mm with Pst, whereas BIO4 and BIO5 achieved modest antibacterial activity (2.8 mm), with no significant difference between them. BIO3 displayed slightly lower efficacy, with a 2.7 mm inhibition area (Figure 1B). All the other extracts did not produce measurable inhibition of bacterial growth.

Among extracts from ornamental plants, A. africanus completely inhibited both conidial germination and mycelial growth. Similarly, A. umbellatus ‘Albus’ totally suppressed conidial germination, though it showed progressive reduction in mycelial growth inhibition, 87.5% at 1 dpi, 32.5% at 2 dpi, and no inhibition at 3 dpi. In contrast, extracts from L. monopetalum, E. nivea, C. cineraria, D. margaretae, and A. unedo were ineffective (Table 2).

Extracts of A. vera (AVE, AG, AP), artichoke (A1, A3), and spent coffee grounds (C1-C3) exhibited none to low antifungal activity, with inhibition values of 0 to 1.7%, 2.4% to 6.5%, and 5.7% to 7.0%, respectively. These results demonstrate the overall inefficacy of these formulations in antimicrobial activity (Table 2).

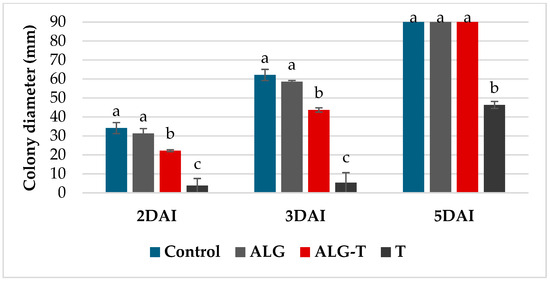

Furthermore, the results of the VOC assay with thyme oil and alginates showed significant inhibitory effects on mycelial growth of Bc, particularly during the early stages (Figure 2). At 2 to 3 dpi, thyme essential oil alone produced an inhibition of about 90%; however, at 5 dpi, the inhibitory effect decreased to 48%, highlighting the transient nature of its volatile components. The thyme oil microencapsulated in alginate gel (ALG-T) did not exhibit the same antifungal efficacy as free thyme oil, showing only ~30% inhibition of mycelial growth at 3 dpi and a complete loss of activity by 5 dpi. Alginate alone showed negligible effects on mycelial growth as compared to the control. Similarly, thyme oil completely suppressed conidial germination while the formulation with alginate showed a minimal inhibitory activity of 8%.

Figure 2.

B. cinerea colony growth inhibition at 2, 3, and 5 days post-inoculation (dpi) following treatment with control (non-treated), ALG (Alginate), ALG-T (Alginate + Thyme), and T (Thyme essential oil). Values are the means of 3 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

3.2. In Vivo Efficacy Evaluation

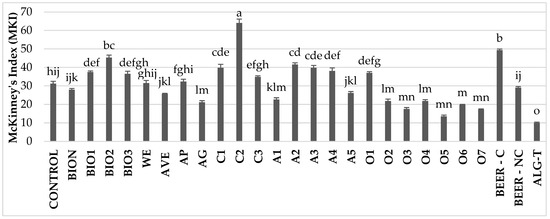

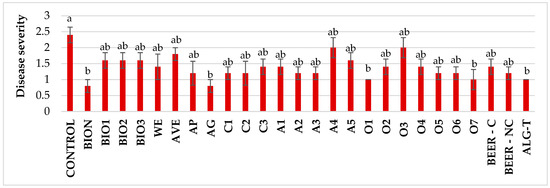

In experiments with various treatments against Bc on artificially inoculated tomato plants, a wide variation in disease incidence was observed across treatments. At the first assessment at 5 dpi, when the untreated plants showed a 31.2% disease incidence, some treatments already demonstrated a clear protective effect (Figure S1). Notably, significant reductions in MKI were recorded in plants treated with the alginate-thyme formulation (ALG-T; −67.9%), A. vera gel (AG; −32.4%), ornamental plant extracts O2, O3, O4, O5, O6, and O7 (ranging from −30.0% to −56.6%), and artichoke extract A1 (−27.6%). In contrast, the remaining treatments either exhibited MKI values significantly higher (C2, BEER-C, BIO1, BIO2, C1, A2, A3, A4, and O1) or no significantly different (BION, AP, BIO3, WE, and BEER-NC) compared to the untreated control (Figure 3). Similar results were obtained with the assessmnent at 7 dpi.

Figure 3.

Disease incidence on tomato plants treated with natural extracts/compounds and inoculated with B. cinerea, assessed at 5 dpi. Values are the mean of 5 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

Regarding the efficacy against Pst, significant differences across treatments were observed (Figure 4 and Figure S2). At 7 dpi the untreated plants showed a MKI of 27%, whereas several treatments already demonstrated clear protective effects. Notably, ALG-T was the most effective treatment, exhibiting a significant reduction in disease incidence (−83.3%) compared to the control. The resistance inducer BION significantly reduced disease incidence by 60.4%. Coffee extracts C1 (−46.9%) and C3 (−44.2%), artichoke extracts A2 (−39.8%), A3 (−46.0%), and A5 (−47.3%), as well as BIO3 (−31.0%), were also effective in controlling the disease. The results at 7 dpi were consistent with previous observations.

Figure 4.

Disease incidence on tomato plants treated with natural extracts/compounds and inoculated with P. syringae pv. tomato, assessed at 7 dpi. Values are the mean of 5 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at p = 0.05.

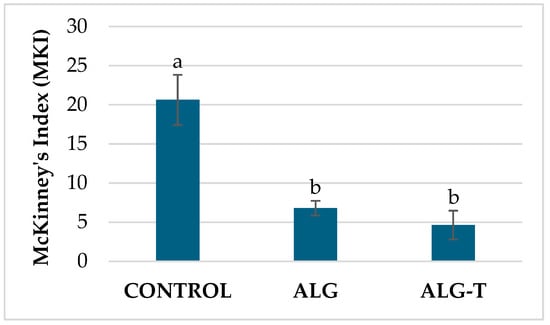

In a subsequent experiment performed against the bacterium, treatments with alginates were taken into consideration. The results demonstrated that both alginate formulations ALG and ALG-T exhibited significant efficacy in disease control. The MKI was maintained at 6.8% for ALG and at 4.6% for ALG-T, both markedly lower than the control (MKI = 20.6%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Disease incidence on tomato plants treated with alginates (ALG) and thyme essential oil microencapsulated in alginate gel (ALG-T) and inoculated with P. syringae pv. tomato. Values are the mean of 5 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

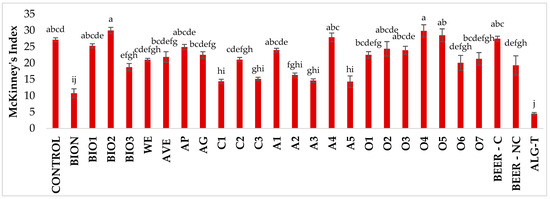

To evaluate the effectiveness of various treatments against PVYC-to, symptom severity was assessed at two time points (Figure 6 and Figure S1). The initial assessment, conducted at 18 dpi, when the untreated plants showed an average disease severity of 2.3, revealed that all treatments reduced average disease severity compared to the untreated control. Statistically significant reductions were observed for plants treated with BION and AG (−66.7%), as well as with O1, O7, and ALG-T (−58.3%). The remaining treatments showed milder effects with no statistical significance. In the second assessment, conducted at 34 dpi, the results showed a notable variability in disease severity across treatments, with AVE and O4 exhibiting the highest disease levels, whereas BIO2 and BIO3 demonstrated the lowest (Figure S4).

Figure 6.

Disease severity on tomato plants treated with natural extracts/compounds and inoculated with PVYC-to at 18 days after inoculation. Values are the mean of 5 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

Following the initial screening, a subsequent experiment was conducted focusing exclusively on the extracts that demonstrated the highest efficacy against PVYC-to in the preliminary tests. Among these, the A. vera gel (AG), ornamental plant extracts O5 and O6, and artichoke-derived extracts A3 and A5 significantly reduced disease severity by 53–59% compared to the untreated control. The average severity levels observed for these treatments were statistically comparable to those achieved with the resistance inducer BION (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Disease severity on tomato plants treated with selected natural extracts/compounds and inoculated with PVYC-to in a second experiment. Values are the mean of 5 replicates. Bars represent standard errors. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

3.3. Gene Expression and Early Post-Treatment Plant Responses

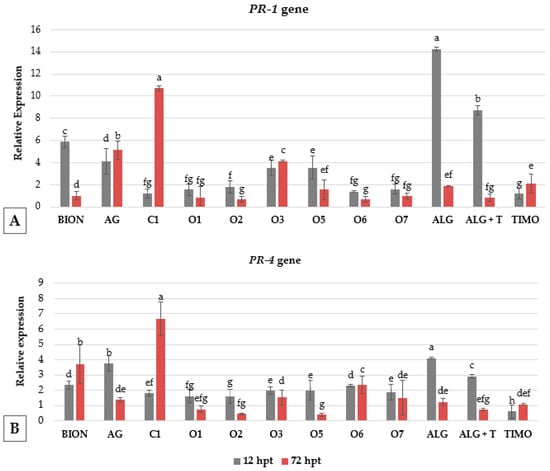

To evaluate the defense-related responses induced by the treatments, a time-course analysis was performed at 12- and 72-h post-treatment (hpt) using PR-1 and PR-4 genes as markers for resistance induction in plants. Overall, PR-1 gene expression showed the strongest changes, with significant variability depending on the compound and timing (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Differential expressions of PR-1 (A) and PR-4 (B) genes in tomato leaves treated with various extracts/compounds, sampled at early (12 hpt) and late (72 hpt) time-points. Relative expression levels are shown following various treatments compared to the untreated control. Error bars represent standard error from three biological replicates. For each of the two-sampling time, columns with the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey’s HSD test at the probability level of p = 0.05.

Alginates, both alone (ALG) and in combination with thyme (ALG-T), induced the highest early overexpression of PR-1 at 12 hpt compared to the control (reaching up to 14.3 and 8.7 relative expression, respectively), followed by BION (5.9), A. vera gel (AG, 4.1), and the ornamentals D. margaretae (O5) and A. umbellatus (O3) showing 3.5 of relative expression. At 72 hpt, PR-1 expression was strongly induced by coffee extract C1 (10.7), and by AG (5.1), and O3 (4.1), indicating a late-phase or sustained induction, while ALG and ALG-T showed reduced elicitation activity at this time point. Notably, BION declined to baseline levels at 72 hpt, suggesting an early transient response.

For PR-4, early induction at 12 hpt was most prominent in ALG (up to 4.2 relative expression), AG (3.8), and ALG-T (2.9), followed by BION, O6, O5, O3, and O7 (1.9–2.3). At 72 hpt, C1 exhibited the highest expression level (6.7), followed by BION (3.7) and O6 (2.4), indicating a late-phase response, whereas most other treatments declined below 2.0 of relative expression (Figure 8).

4. Discussion

The increasing concerns regarding the environmental and human health impacts of synthetic pesticides necessitate the development and implementation of sustainable alternatives, a goal resonating with the objectives of the European Green Deal [31,32]. This urgency is further amplified by the growing threats of climate change, which exacerbate pathogen spread and pesticide resistance, demanding resilient and adaptive agricultural solutions [6]. This research comprehensively investigated the antimicrobial and plant resistance-inducing capabilities of various natural products, including essential oils, plant extracts, and biostimulants, against critical tomato phytopathogens: the fungus Bc, the bacterium Pst, and the virus PVY. The findings highlight the potential of bio-based substances as effective disease management tools in agriculture, contingent upon strategic formulation to enhance stability and efficacy.

In vitro analyses revealed that EOs derived from thyme (T. vulgaris), lavender (L. angustifolia), and tea tree (M. alternifolia) exhibited significant antifungal activity against Bc. The inhibition areas observed in disk diffusion assays against Bc corroborate previous reports attributing potent antifungal properties to thymol, carvacrol, and terpinen-4-ol, known to disrupt fungal membrane integrity and oxidative homeostasis [33,34]. Similarly, thyme and tea tree oils demonstrated bactericidal activity against Pst, aligning with prior studies indicating the ability of EOs to inhibit bacterial quorum sensing, adhesion, and biofilm formation [35].

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted from thyme essential oil (EO) demonstrated strong antifungal activity in non-contact assays, achieving approximately 90% inhibition of Bc during early stages. However, efficacy declined rapidly to ~48% at 5 days post-treatment (DPT), likely due to the high volatility of the EO. Alginate alone, while not directly antifungal, contributed to disease mitigation in planta—possibly through moisture regulation and physical barrier effects [24,36]. Although some of the literature highlights the potential of carrier systems to enhance EO performance, our results suggest that the combined use of thyme EO and alginate, as formulated in our study, did not yield improved antifungal efficacy. Specifically, when thyme EO was microencapsulated in alginate beads (ALG-T), its in vitro activity was significantly reduced, showing only 30% inhibition at 3 days post-inoculation (dpi) and complete loss of activity by 5 dpi. This reduction cannot be attributed solely to slower EO release; rather, the residual effects observed in planta may stem from resistance induction mechanisms triggered by alginate itself. While alginate is not inherently antifungal, it may influence plant defense responses through its physical and biochemical properties. Direct application of thyme EO to plant tissues, by contrast, is expected to exert measurable antifungal effects, and immersion treatments which involve direct exposure of plant tissues to EO solutions, may additionally stimulate protective responses. Overall, our findings indicate that although encapsulation can mitigate volatility, it does not necessarily preserve EO efficacy. The role of alginate as a carrier system requires further optimization, as our formulations did not outperform alginate alone. VOC assays confirmed the potent antifungal activity of thyme EO, and alginate demonstrated resistance-inducing properties that contributed to disease reduction on tomato plants. However, the expected synergistic effect between EO and alginate, as suggested in the literature, was not observed in our trials, underscoring the need for reformulation strategies to improve performance.

Furthermore, EOs like tea tree, thyme, rosemary, lavender, and laurel effectively suppressed mycelial growth of Bc, achieving complete inhibition, with rosemary oil’s efficacy attributed to its antimicrobial constituents such as 1,8-cineole and camphor disrupting hyphal development [37]. Conidial germination assays demonstrated the superior efficacy of thyme oil, achieving complete inhibition.

Interestingly, wood extract surpassed the in vitro efficacy of the biostimulants BIO4, BIO5 against bacterial strains, while plant extracts rich in polyphenols in all the biostimulants tested and in the wood extract achieved complete growth inhibition, further validating the antimicrobial potency of some botanical extracts [38,39]. Complementing these findings, biostimulants (BIO1-BIO3) also achieved direct antimicrobial activity.

In vivo studies presented a more complex scenario, with treatment effectiveness varying under physiological conditions and revealing pathogen-specific responses. Against Bc, most treatments showed limited suppression, with the highest disease severity observed in C2 and BEER-C. However, ALG–T, ornamental extracts O2–O7, A. vera gel, and artichoke extracts A1 significantly reduced symptoms, possibly indicating antifungal activity and potential induction of defensive mechanisms in plants, including the activation of antimicrobial secondary metabolites and pathogenesis-related proteins [15,17,18,19,20,22,40,41]. Regarding substrates such as C2 or beer, these may contain nutrients for pathogens or influence plant physiology by rendering the plant more susceptible to fungal growth. Alternatively, certain extract components may interfere with plant defense signals, indicating that the chemical composition of the treatment is critical in determining whether it improves resistance or unintentionally increases pathogen development.

For Pst, BION, ALG–T, coffee extracts C1 and C3, and artichoke extracts A2, A3 and A5 showed notable disease suppression likely due to their higher concentrations of antimicrobial terpenoids and flavonoids [39,42]. It can be stated that the composition of all plant extracts should be correlated with their chemical profile, which will be the subject of future research. In that study, the costs associated with achieving efficacy or biological activity will also be related to the presence of specific compounds. In this study, the efficacy of artichoke extracts was not related to their total content of polyphenols. The biostimulants, such as BIO1, BIO2, BIO3, BIO4, and BIO5, deserve attention: some, like BIO1, have shown effects on conidial germination, while for others, the necessary data are not yet available. In general, for these complex extracts, even without precise quantification of individual compounds, the observed antimicrobial effects can be attributed to the presence of terpenoids, flavonoids, and other bioactive metabolites.

Alginate-based formulations likely enhanced stability and delivery of thyme EO, aligned with findings by Benavides et al. [43], who demonstrated that alginate beads can effectively encapsulate essential oils, prolonging their antimicrobial activity through controlled release. These formulations may also function as activators of plant immunity in addition to physical stabilization. Alginate and its derivatives can initiate SA-dependent defense pathways, which help to induce resistance against a variety of pathogens, according to Saberi Riseh et al.. [44]. Similarly, Dawood et al. [40] emphasized alginate’s dual function as a natural elicitor and biocompatible carrier that can alter hormonal signaling and activate genes involved in plant defense in response to biotic stress.

BION, AG, and ALG–T significantly reduced the severity of infection caused by PVYC-to early on, with BIO2 showing complete symptoms absence at later stages. Extracts from artichoke and ornamental plants, even if with variable results in repeated experiments, also showed efficacy in the reduction in disease severity. Selected extracts (AG, O1, O7, ALG-T) matched BION in efficacy, supporting their role in SAR activation [45].

Ornamental plant extracts, particularly A. africanus, demonstrated potent antifungal activity, achieving complete inhibition of Bc conidial germination and mycelial growth in vitro and significant symptom reduction in planta. These results suggest the presence of novel bioactive compounds with potential antimicrobial activity. While their mechanisms remain underexplored, their consistent performance across assays supports further investigation into their phytochemical profiles and signaling effects [46].

Gene expression profiling revealed nuanced temporal dynamics in the regulation of PR-1 and PR-4 genes—key markers of systemic acquired resistance (SAR). Early activators such as alginate formulations and AG rapidly induced strong expression, suggesting activation of SA-dependent signaling pathways [45,47,48]. This rapid onset positions ALG-based treatments as effective initiators of defense, capable of triggering early immune responses. This is consistent with findings that alginate systems can enhance PR gene expression [40,44] and stabilize volatile bioactive compounds such as essential oils, improving their retention and controlled release [43]. BION exhibited a transient spike in PR-1 gene expression, consistent with its role as a short-term plant inducer that activates SA signaling without prolonged stimulation [40]. In contrast, coffee extract C1 led to delayed but sustained gene activation for both markers of SAR and ISR pathways, PR-1 and PR-4, indicating its potential for maintaining long-term resistance through extended signaling cascades. This extended activation may involve crosstalk between SA and JA/ET pathways, enhancing basal resistance. Medeiros et al. [49] found that a formulation of coffee-leaf extract, resulted in a sustained upregulation of several defense-related genes, including PR-4, in tomato plants for a duration of up to five days following treatment. Furthermore, according to Gammoudi et al. [21], coffee extracts have been shown to trigger physiological responses in different plant species. This latter study reported that extracts from spent coffee grounds improved germination and early seedling growth in Capsicum annuum under salt and drought stress, suggesting a wider priming effect. Overall, these findings show that coffee extracts can initiate both immediate and lasting defense responses, supporting the significant late-phase activation we observed in our study. Differences in efficacy observed between in vitro and in vivo models likely arise from the phytochemical composition of coffee extract, which affects absorption, distribution, metabolism, and overall bioactivity. The coffee extract is rich in chlorogenic acids, caffeine, and other phenolic compounds [50,51], which are known for their antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties rather than direct antimicrobial activity. These compounds did not exert strong bactericidal effects under in vitro conditions, yet they effectively induced plant immune responses, as evidenced by PR gene overexpression. Such systemic activation suggests engagement of SA and JA/ET pathways, consistent with polyphenol-mediated defense induction [38], and aligns with previous findings on the role of extract formulation in enhancing plant immunity [40,44]. Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of tailoring the extract’s composition to its intended application—whether for rapid pathogen suppression or long-term immune induction—thereby highlighting the strategic role of phytochemical profiling in biostimulant design.

These expression patterns highlight the importance of strategic timing of resistance-inducing treatments. The long-term effects of repeated applications of these potential resistance inducers require more research, especially in terms of their effects on plant immunity and overall physiological balance. Frequent applications of ALG-based formulations may enhance immediate defense, while spaced applications of C1 could help sustain basal immunity. However, repetitive elicitor use must be carefully managed to avoid receptor desensitization or metabolic overload, as discussed by Walters et al. [45], who emphasized that overstimulation of plant defenses can lead to growth penalties and reduced fitness. As noted by Ranatnuge and Hasara [52], optimizing application intervals based on immune response kinetics can amplify efficacy while preserving plant health. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of plant responses to these treatments, future studies should also incorporate transcriptomic analyses, which can reveal the range and dynamics of gene expression changes beyond specific markers.

The formulation characteristics of the treatments, particularly the role of alginate encapsulation, may explain the observed expression patterns. The reduction in disease incidence across all three pathogens suggests that alginate primarily contributed through resistance induction by modulating immune-mediated signaling, while thyme essential oil provided direct antimicrobial activity. Although the in vivo antifungal efficacy of thyme oil applied to soil was not specifically assessed in this study, its known bioactive constituents, such as thymol and carvacrol, are well documented to inhibit pathogens and interact with root tissues and soil microbiota, as confirmed by in vitro results. Encapsulation in alginate may have further enhanced the formulation by stabilizing thyme essential oil, reducing volatility and phytotoxicity, and sustaining its bioactivity; however, the results also highlight the need for further improvements in the formulation [44,53]. These findings highlight the importance of delivery systems in optimizing elicitor performance.

In line with these findings, the present study demonstrated that A. vera extracts primarily stimulated host defense mechanisms, as evidenced by the upregulation of defense-related gene expression. These findings align with those demonstrating that aloe-derived polysaccharides in tomato plants activate disease-associated proteins and mitigate symptom severity [19]. Although our study utilized whole gel rather than isolated compounds, similar active compounds may have caused the effects we observed. Collectively, these results suggest that A. vera gel functions predominantly as an inducer of host resistance rather than as a direct antimicrobial agent, despite previous reports of antimicrobial activity under specific experimental conditions [18,54].

In summary, the study evaluated various natural extracts as sustainable alternatives to synthetic compounds against Bc, Pst, and PVYC-to. In vitro, thyme, lavender, and tea tree EOs were effective against Bc, with thyme and tea tree also showing bactericidal activity against Pst; thyme EO’s volatiles provided strong initial antifungal activity but declined due to volatility. In vivo, ALG–T, ornamental extracts, AG, and artichoke significantly reduced Bc symptoms, while BION, ALG–T, coffee, and artichoke extracts were notable against Pst. For PVYC-to, BION, AG, and ALG–T decreased severity, and BIO2 ultimately prevented symptoms. Alginate contributed to disease mitigation through the possible activation of salicylic acid-dependent defenses and PR gene expression, although encapsulation sometimes reduced the activity of thyme EO, suggesting that formulation optimization is needed. Coffee extract, rich in polyphenols, induced delayed but sustained activation of SAR and ISR pathways, indicating potential for long-term resistance. These findings underscore the importance of strategic formulation and timing to enhance both direct antimicrobial effects and plant defense induction for effective disease management.

Taken together, these findings emphasize the multifaceted potential of natural products—particularly thyme EO, Agapanthus extracts, and alginate-based delivery systems—as bioactive elicitors and protective agents. Their ability to activate early defense responses, suppress pathogen development, and maintain efficacy through formulation strategies positions them as promising components in sustainable crop protection programs [55,56].

5. Conclusions

This study confirms the substantial antimicrobial potential of natural products, notably thyme essential oil, Agapanthus spp. extracts, artichoke derivatives, and coffee extract against economically significant tomato pathogens. While in vitro results were more consistently positive, in vivo assays emphasized the critical importance of formulation and application methods. The consistent performance of alginate-encapsulated thyme oil across fungal, bacterial, and viral models underscores the value of carrier systems in enhancing stability and controlling release. Moreover, such systems help translate efficacy from tightly controlled laboratory and greenhouse settings to the more unpredictable and variable conditions encountered in the field.

Moreover, treatments such as A. vera gel, coffee extract C1, and BION demonstrated resistance-inducing effects through the induction of defense-related genes, notably PR-1 and PR-4, with C1 showing sustained activation linked to its unique phytochemical profile. These findings highlight the importance of aligning extract chemistry with intended application, whether for direct microbial suppression or long-term plant resistance induction, and optimizing dosage and timing to avoid overstimulation of receptors and reduce metabolic stress.

Future research should prioritize long-term field trials, compound isolation, and the elucidation of synergistic interactions among bioactives. Further investigations could incorporate chemical characterization analyses to assess the efficacy of specific antimicrobial compounds and to account for variability resulting from extract composition or extraction methodology. Integrating these treatments into pest management programs could offer sustainable, eco-friendly alternatives to synthetic pesticides, aligning with the principles of integrated pest management (IPM) and the goals of green agriculture, while addressing the dual challenges of food security and climate change mitigation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15102342/s1, Supplementary File S1: Extraction protocols for plant-based materials; Figures S1–S4: Disease severity on tomato plants treated with natural extracts/compounds and inoculated with PVYc-to at 34 days after inoculation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.C., R.M.D.M.A., F.F. and C.B.; methodology and validation, C.B., R.M.D.M.A., F.F., D.E.C., T.M. and A.A.L.; investigation, C.B., S.L., L.V., P.R.R., M.D. and M.M.; data curation and formal analysis, C.B., S.L., and L.V.; resources, D.E.C., R.M.D.M.A., S.P., R.S., T.M. and A.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B., R.M.D.M.A., F.F., D.E.C., S.P., R.S., T.M. and A.A.L.; visualization, C.B.; supervision, R.M.D.M.A., P.R.R., F.F. and D.E.C.; project administration and funding acquisition, R.M.D.M.A., and D.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR)—MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4—D.D. 1032 17/06/2022, CN00000022)—CUP H93C22000440007. and by Product and process innovation in organic floricolture for public green spaces, healing e kitchen garden BIOGARDEN (MASAF Progetti di Ricerca in agricoltura Biologica Avviso pubblico per la concessione di contributi per la ricerca in agricoltura biologica n. 9220340 del 8 ottobre 2020—CUP H93C24000920001). Christine Bilen was supported by a PhD fellowship granted by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—PNRR, Mission 4, component 2 “From Research to Enterprise”—Investment 3.3 “Introduction of innovative doctorates that respond to the innovation needs of companies and promote the recruitment of researchers from companies”—CUP H91I22000070007 and by TIMAC AGRO Italia S.p.A.

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated in this study are provided within the manuscript or Supplementary Information files.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the companies and collaborators who generously provided botanical extracts and essential oils used in this study. We are grateful to Giuseppe De Mastro and Laura Scalvenzi for providing the artichoke water extract, Café Chic for supplying the raw coffee material, and Fabrizio Pellegrino (Hekomia, Ostuni, BR, Italy) for kindly providing essential oils.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Daniel El Chami was employed by the company TIMAC AGRO Italia S.p.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Rockström, J.; Williams, J.; Daily, G.; Noble, A.; Matthews, N.; Gordon, L.; Wetterstrand, H.; DeClerck, F.; Shah, M.; Steduto, P.; et al. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 2017, 46, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOLAW)—Systems at Breaking Point; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb7654en/cb7654en.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: Concepts, principles and evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2008, 363, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, A.J.; Watson, J.; Lobell, D.B.; Howden, S.M.; Smith, D.R.; Chhetri, N. A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahlali, R.; Taoussi, M.; Laasli, S.-E.; Gachara, G.; Ezzouggari, R.; Belabess, Z.; Aberkani, K.; Assouguem, A.; Meddich, A.; El Jarroudi, M.; et al. Effects of climate change on plant pathogens and host-pathogen interactions. Crop Environ. 2024, 3, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, C.; El Moujabber, M.; Ben Slimen, A.; Incerti, O.; Jreijiri, F.; Choueiri, E. Detecting new emerging viruses and phytoplasmas of grapevine in Lebanon for developing future adaptation strategies to climate change. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E. Integrated benefits to agriculture with Trichoderma and other endophytic or root-associated microbes. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, P. Chemical warfare or modulators of defense responses—The function of secondary metabolites in plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System; COM(2020) 640 Final European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Osbourn, A.E. Saponins and plant defence—A soap story. Trends Plant Sci. 1996, 1, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, W.E.; Dong, X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallad, G.E.; Goodman, R.M. Systemic acquired resistance and induced systemic resistance in conventional agriculture. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztahelyi, T.; Holb, I.J.; Pócsi, I. Secondary metabolites in fungus-plant interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi Riseh, R.; Gholizadeh Vazvani, M.; Ebrahimi-Zarandi, M.; Skorik, Y.A. Alginate-induced disease resistance in plants. Polymers 2022, 14, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanò, R.; Ferrara, M.; Gallitelli, D.; Mascia, T. The role of grafting in the resistance of tomato to viruses. Plants 2020, 9, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D.; Díaz-Mula, H.M.; Guillén, F.; Zapata, P.J.; Castillo, S.; Serrano, M.; Valero, D.; Martínez-Romero, D. Reduction of nectarine decay caused by Rhizopus stolonifer, Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium digitatum with Aloe vera gel alone or with the addition of thymol. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 151, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, G.; Abbas, H.T.; Ali, I.; Waseem, M. Aloe vera gel enriched with garlic essential oil effectively controls anthracnose disease and maintains postharvest quality of banana fruit during storage. Hort. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz, C.; Felipini, R.B.; Costa, M.E.B.; Di Piero, R.M. Polysaccharides from Aloe barbadensis reduce the severity of bacterial spot and activate disease-related proteins in tomato. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 94, 387–393. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20123315709 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Uda, M.N.A.; Shaari, N.H.; Said, N.S.; Ibrahim, N.H.; Akhir, M.A.; Hashim, M.K.R.; Gopinath, S.C. Antimicrobial activity of plant extracts from Aloe vera, Citrus hystrix, Sabah snake grass and Zingiber officinale against Pyricularia oryzae that causes rice blast disease in paddy plants. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 318, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammoudi, N.; Nagaz, K.; Ferchichi, A. Potential use of spent coffee grounds and spent tea leaves extracts in priming treatment to promote in vitro early growth of salt- and drought-stressed seedlings of Capsicum annuum L. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2021, 12, 3341–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanò, R.; Gena, P.; Linsalata, V.; Sini, V.; D’Antuono, I.; Cardinali, A.; Cotugno, P.; Calamita, G.; Mascia, T. Spotlight on secondary metabolites produced by an early-flowering Apulian artichoke ecotype sanitized from virus infection by meristem-tip-culture and thermotherapy. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopedota, A.A.; Arduino, I.; Lopalco, A.; Iacobazzi, R.M.; Cutrignelli, A.; Laquintana, V.; Racaniello, G.F.; Franco, M.; la Forgia, F.; Fontana, S.; et al. From oil to microparticulate by prilling technique: Production of polynucleate alginate beads loading Serenoa Repens oil as intestinal delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 599, 120412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-García, S.; Moumni, M.; Romanazzi, G. Antifungal activity of volatile organic compounds from essential oils against the postharvest pathogens Botrytis cinerea, Monilinia fructicola, Monilinia fructigena, and Monilinia laxa. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1274770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, T.; Finetti-Sialer, M.M.; Cillo, F.; Gallitelli, D. Biological and molecular characterization of a recombinant isolate of Potato virus Y associated with a tomato necrotic disease occurring in Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 92, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, H.H.; Davis, R.J. Influence of soil temperature and moisture on infection of young wheat plants by Ophiobolus graminis. J. Agric. Res. 1925, 31, 827–840. [Google Scholar]

- Molinari, S.; Fanelli, E.; Leonetti, P. Expression of tomato salicylic acid (SA)-responsive pathogenesis-related genes in Mi-1-mediated and SA-induced resistance to root-knot nematodes. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 15, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, S.; Dong, C.; Li, B.; Dai, H. A PR-4 gene identified from Malus domestica is involved in the defense responses against Botryosphaeria dothidea. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 62, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.; Ortiz, J.; Saavedra, N.; Salazar, L.A.; Meneses, C.; Arriagada, C. Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR in Solanum lycopersicum L. inoculated with the mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 101, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Green Deal; COM(2019) 640 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tataridas, A.; Kanatas, P.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Zannopoulos, S.; Travlos, I. Sustainable crop and weed management in the era of the EU Green Deal: A survival guide. Agronomy 2022, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, V.K.; Kang, S.; Xu, H.; Lee, S.G.; Baek, K.H.; Kang, S.-C. Potential roles of essential oils on controlling plant pathogenic bacteria Xanthomonas species: A review. Plant Pathol. J. 2011, 27, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, J.S.; Karuppayil, S.M. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1451–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotor-Vila, A.; Teixidó, N.; Usall, J.; Torres, R.; Viñas, I. Antifungal activity of volatile organic compounds from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CPA-8 against postharvest pathogens of cherry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 265, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, S.; Subramanyam, V.R.; Kole, C.R. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of aromatic constituents of essential oils. Microbios 1997, 89, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.F.A.; Muhammed, M.; Mitra, D.; Mir, M.I.; Thabet, S.G. Alginate-induced immunity: A new frontier in plant health. In Elicitors for Sustainable Crop Production; Abd-Elsalam, K.A., Mohamed, H.I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegne, G.; Pretorius, J.C.; Swart, W.J. Antifungal properties of Agapanthus africanus L. extracts against plant pathogens. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides, S.; Cortés, P.; Parada, J.; Franco, W. Development of alginate microspheres containing thyme essential oil using ionic gelation. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi Riseh, R.; Ebrahimi-Zarandi, M.; Tarkka, M.T. Actinobacteria as effective biocontrol agents against plant pathogens: An overview on their role in eliciting plant defense. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.R.; Ratsep, J.; Havis, N.D. Controlling crop diseases using induced resistance: Challenges for the future. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1263–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, D.; Bautista-Baños, S. A review on the use of essential oils for postharvest decay control and maintenance of fruit quality during storage. Crop Prot. 2014, 64, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Khurana, J.P. Role of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins in plant defense mechanism. In Molecular Aspects of Plant-Pathogen Interaction; Singh, A., Singh, I.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Mou, Z. Salicylic acid and its function in plant immunity. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, F.C.L.; Resende, M.L.V.; Medeiros, F.H.V.; Zhang, H.M.; Paré, P.W. Defense gene expression induced by a coffee-leaf extract formulation in tomato. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 74, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.; Donangelo, C.M. Phenolic compounds in coffee. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M. Functional properties of coffee and coffee by-products. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranatnuge, R.; Hasara, H. Biostimulants in sustainable agriculture: Emerging roles and mechanisms. Discov. Agric. 2024, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Jabeur, M.; Ghabri, E.; Myriam, M.; Hamada, W. Thyme essential oil as a defense inducer of tomato against gray mold and Fusarium wilt. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 94, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saks, Y.; Barkai-Golan, R. Aloe vera gel activity against plant pathogenic fungi. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1995, 6, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltos-Rezabala, L.A.; Da Silveira, P.R.; Tavares, D.G.; Moreira, S.I.; Magalhães, T.A.; Botelho, D.M.S.; Alves, E. Thyme essential oil reduces disease severity and induces resistance against Alternaria linariae in tomato plants. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Khan, A.; Asif, M.; Khan, F.; Ansari, T.; Shariq, M.; Siddiqui, M.A. Biological control: A sustainable and practical approach for plant disease management. Acta Agric. Scand. B 2020, 70, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).