Study of Wine Producers’ Marketing Communication in Extreme Territories–Application of the AGIL Scheme to Wineries’ Website Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Selection

2.2. Statistical Population

2.3. Focus Groups and Selection of Participants

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

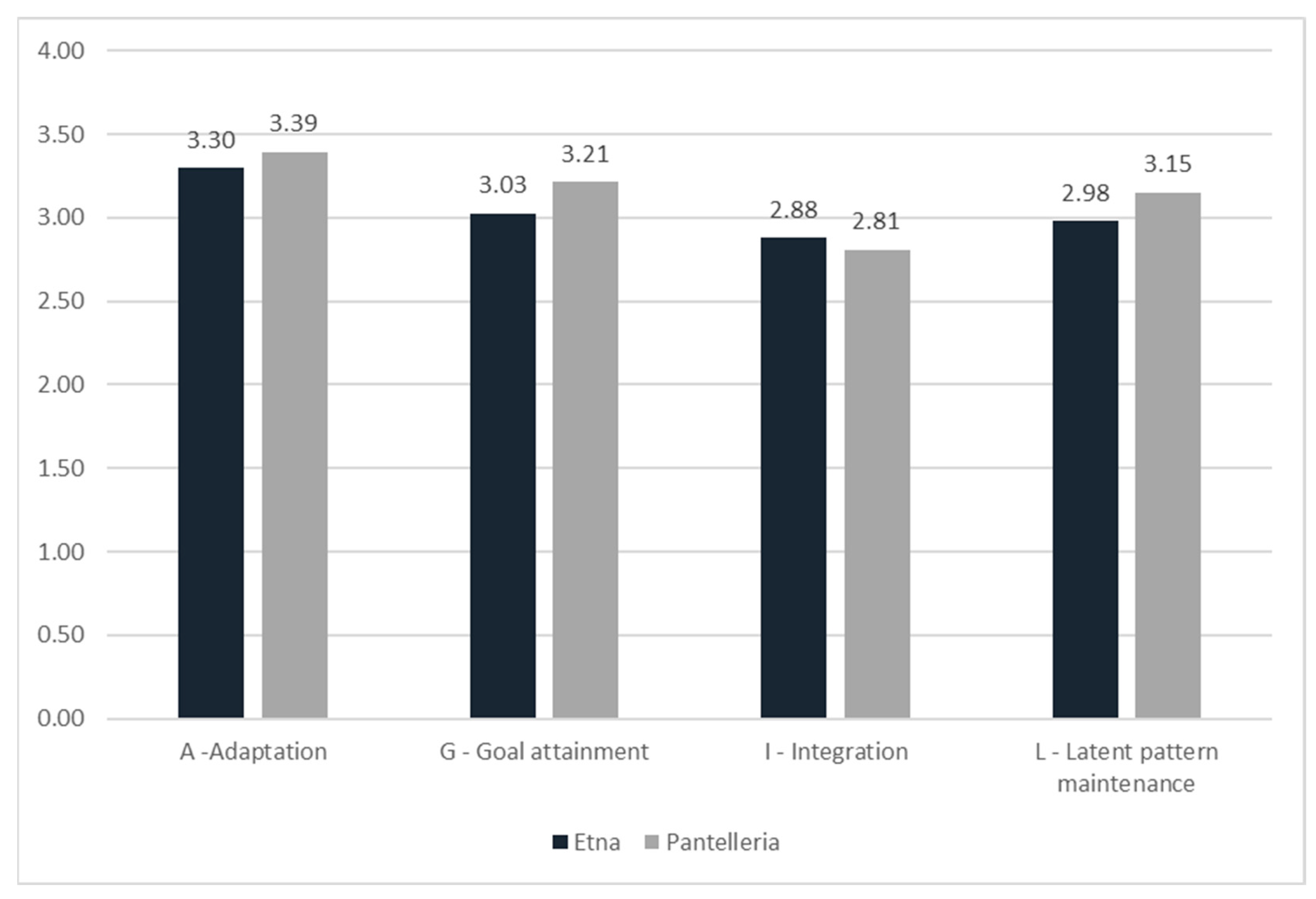

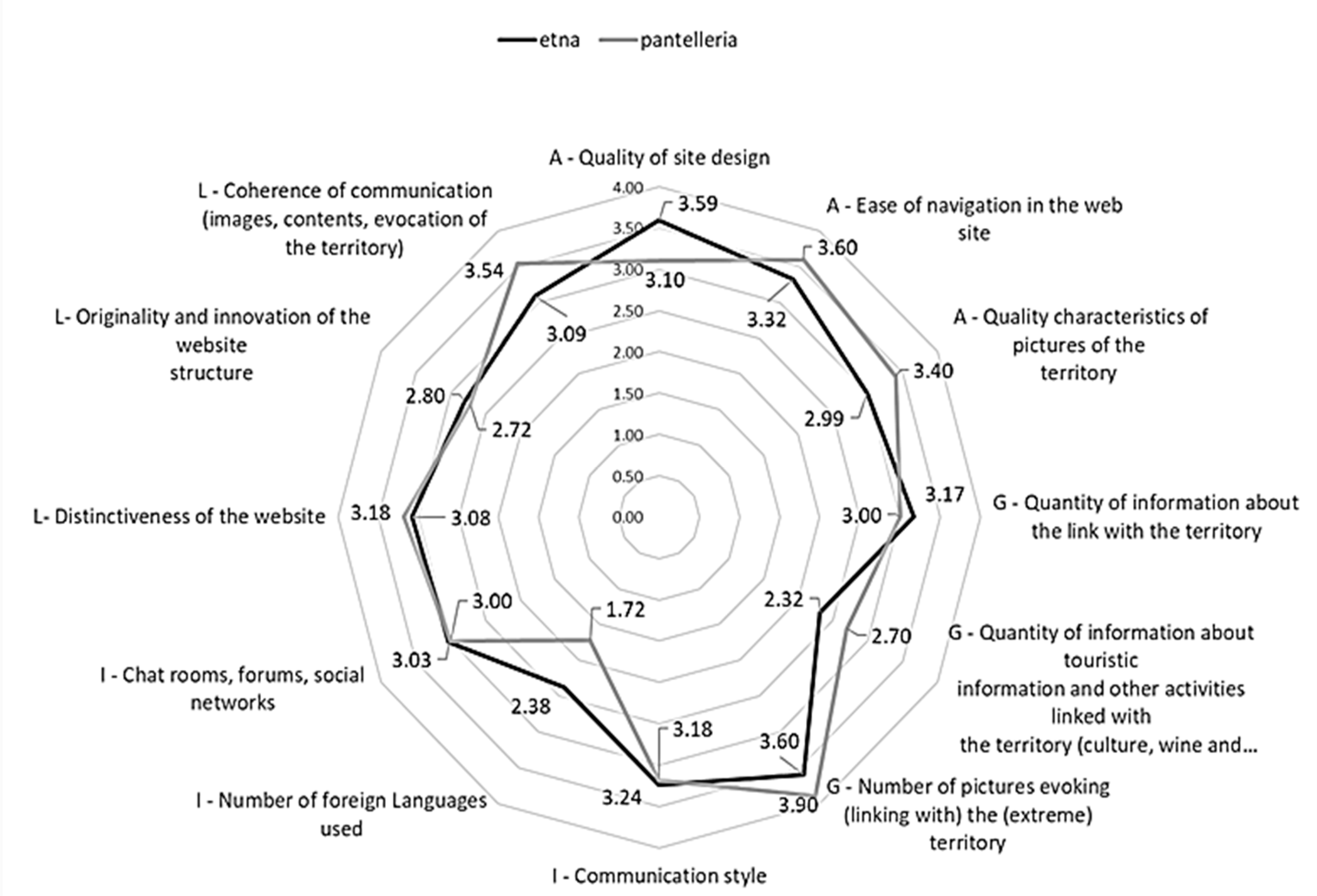

3. Results

4. Discussion

- poor communication of the heroic nature of viticulture practiced in the territory,

- lack of coordination between the entrepreneur and the designer of the website,

- a lack of strong identifying elements that allow visitors to properly distinguish the winery from others, except through the brand name,

- a lack of information on activities that affect the territory of origin,

- limited use of foreign languages.

- small dimension of firms and territory dedicated to wine production,

- lack of funding for territorially coordinated communication activities,

- limited use of foreign languages.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaudour, E. The quality of grapes and wine in relation to geography: Notions of terroir at various scales. J. Wine Res. 2002, 13, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Seguin, G. The concept of terroir in viticulture. J. Wine Res. 2006, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunc, M.; Menival, D.; Charters, S. Champagne: The challenge of value co-creation through regional brands. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviezzo, A.; Garofano, A.; Granata, J.; Kakavand, S. Using terroir to exploit local identity and cultural heritage in marketing strategies: An exploratory study among Italian and French wine producers. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2017, 13, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C. The Business of Wine Tourism: Evolution and Challenges. In Management and Marketing of Wine Tourism Business; Sigala, M., Robinson, N.S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S. Marketing Terroir: A Conceptual Approach. In Proceedings of the 5th International Academy of Wine Business Research Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 8–10 February 2010; Available online: http://academyofwinebusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Charters-Marketing-terroir.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorrano, P.; Fait, M.; Maizza, A.; Vrontis, D. Online branding strategy for wine tourism competitiveness. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warman, R.; Lewis, G.K. Wine place research: Getting value from terroir and provenance in premium wine value chain interventions. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2019, 31, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Hanning, R.; Tsuji, L. Prevalence and severity of household food insecurity of First Nations People living in an on-reserve, sub-Arctic community within the Mushkegowuk Territory. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capece, A.; Romaniello, R.; Siesto, G.; Romano, P. Diversity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts associated to spontaneously fermenting grapes from an Italian heroic vine-growing area. Food Microbiol. 2012, 31, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero delle Politiche Agricole Alimentari e Forestali [“Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies”]. Disciplina Organica della Coltivazione della Vite e della Produzione e del Commercio del Vino [“Organic regulation of grape cultivation and wine production andtrade”]. Available online: https://www.politicheagricole.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/12012 (accessed on 3 September 2019).

- Barbera, G.; Cullotta, S.; Rossi-Doria, I.; Rühl, J.; Rossi-Doria, B. In I paesaggi a terrazze in Sicilia: Metodologie per l’analisi, la tutela e la valorizzazione [“The Sicilian Terraced Landscapes: Methodology for Their Analysis, Protection, and Valorisation”]. In Collana Studi e Ricerche; ARPA Publisher: Palermo, Italy, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- EATALY Magazine. Alla Scoperta dei Vini Eroici [“Discovering Heroic Wines”]. Available online: https://www.eataly.net/it_it/magazine/eataly-racconta/cosa-sono-i-vini-eroici/ (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Parco dell’Etna [“The Etna Regional Park”]. Available online: http://www.parcoetna.it/default.aspx (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- UNESCO [United Nation Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization]. World Heritage List. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1427 (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Stupino, M.; Giacosa, E.; Pollifroni, M. Tradition and innovation within the wine sector: How a strong combination could increase the company’s competitive advantage. In Processing and Sustainability of Beverages; Grumezescu, A., Holban, A.-M., Eds.; Woodhead: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terraces and Landscapes. Available online: http://www.terracedlandscapes2016.it/en/pantelleria/ (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- Oliveri, C.; Bella, P.; Tessitori, M.; Catara, V.; La Rosa, R. Grape and environmental mycoflora monitoring in old, traditionally cultivated vineyards on mount Etna, Southern Italy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 97, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottini, V.A.; Barbierato, E.; Bernetti, I.; Capecchi, I.; Fabbrizzi, S.; Menghini, S. Winescape perception and big data analysis: An assessment through social media photographs in the Chianti Classico region. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. Special Issue: Wine tourism: Moving beyond the cellar door? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 338–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsana, L.; Jolibert, A. The effects of expertise and brand schematicity on the perceived importance of choice criteria: A Bordeaux wine investigation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.K.; Byrom, J.; Grimmer, M. Collaborative marketing in a premium wine region: The role of horizontal networks. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, J.M.; Costa, C.; Buhalis, D. Network analysis and wine routes: The case of the Bairrada Wine Route. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Fernández, R.; Vriesekoop, F.; Urbano, B. Social media as a means to access millennial wine consumers. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Buil, I.; de Chernatony, L. Consumer engagement with self-expressive brands: Brand love and WOM outcomes. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2014, 23, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Quinton, S. Let’s talk about wine: Does Twitter have value? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentina, I.; Guilloux, V.; Micu, A.C. Exploring social media engagement behaviors in the context of luxury brands. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media: Communication strategies, engagement and future research directions. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Taits, D.; Nagel, M.; Fortunato, A. Using social media in the wine business. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Krajsic, V. Website and social media usage: Implications for the further development of wine tourism, hospitality, and the wine sector. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, L.; Dreyer, A.; Pechlaner, H.; Schamel, G. Wein und Tourismus: Eine Wertschöpfungspartnerschaft zur Förderung regionaler Wirtschaftskreisläufe. In Proceedings of the Tagungsband anlässlich des 3. Symposiums des Arbeitskreises Weintourismus der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Tourismuswissenschaft (DGT), Bolzano, Italy, 24 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Canovi, M.; Pucciarelli, F. Social media marketing in wine tourism: Winery owners’ perceptions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, L.; Madill, J. Using winery web sites to attract wine tourists: An international comparison. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Altamore, L.; Bacarella, S.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S. The Wine Routes in Sicily as a tool for Rural development: An Exploratory Analysis. In Proceedings of the X International Agriculture Symposium “AGROSYM 2019”, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 3–6 October 2019; Available online: http://agrosym.ues.rs.ba/agrosym/agrosym_2019/BOOK_OF_PROCEEDINGS_2019_FINAL.pdf?fbclid=IwAR0FszNGDBh6a5HOkE2aWOGYlUTccJToaMpM-4-DVBYNFlT0mdOB8xxW8tk (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Westbrook, R.A.; Oliver, R.L. The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Customer-centric offer design: Meeting expectations for a wine bar and shop and the relevance of hybrid offering components. Int. J. Wine Bus. 2019, 31, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, M. Prosumers in the wine market: An explorative study. Wine Econ. Policy 2016, 5, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamore, L.; Ingrassia, M.; Chironi, S.; Columba, P.; Sortino, G.; Vukadin, A.; Bacarella, S. Pasta experience: Eating with the five senses—A pilot study. AIMS Agric. Food 2018, 3, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Prayag, G.; Disegna, M. Why wine tourists visit cellar doors: Segmenting motivation and destination image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T.; Canziani, B.; Boles, J.S.; Williamson, N.C.; Sonmez, S. Wine tourist valuation of information sources: The role of prior travel. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2017, 29, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortino, G.; Allegra, A.; Inglese, P.; Chironi, S.; Ingrassia, M. Influence of an evoked pleasant consumption context on consumers’ hedonic evaluation for minimally processed cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) fruit. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1141, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chironi, S.; Ingrassia, M. Study of the importance of emotional factors connected to the colors of fresh-cutcactus pear fruits in consumer purchase choices for a marketing positioning strategy. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1067, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarini, R.; Carbognin, C.; Casarotti, E.M.; Nicolis, E.; Nencini, A.; Meneghini, A.M. The emotional response to wine consumption. Food Quality Prefer. 2010, 21, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Bacarella, S.; Chironi, S. The communicative power of an extreme territory–the Italian island of Pantelleria and its passito wine. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Choi, S.M.; Lin, J.S. The interplay of culture and situational cues in consumers’ Brand evaluation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F. Methodology and Sociological Research; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Merton, R. Mass Communication Popular Taste and Organized Social Action; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Münch, R. Theory of Action: Towards a New Synthesis Going Beyond Parsons; Routledge Revivals: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T. An outline of the social system. In Theories of Society; Parsons, T., Shils, E., Naegele, K.D., Pitts, J.R., Eds.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T. Societies: Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Martelli, S. Multidimensional Communication: Websites of Public Institutions and Enterprises; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grosso, C.; Signori, P. Analisi multidimensionale della conversazione di marca nei Social Network. In Proceedings of the L’innovazione per la Competitività Delle Imprese, Ancona, Italy, 24–25 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neuninger, R.; Mather, D.; Duncan, T. Consumer’s scepticism of wine awards: A study of consumers’ use of wine awards. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Living within blurry boundaries: The value of distinguishing between qualitative and quantitative research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2018, 12, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.W.; Shamdasani, P.N. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chironi, S.; Bacarella, S.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Ingrassia, M. Study of product repositioning for the Marsala Vergine DOC wine. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 32, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chironi, S.; Bacarella, S.; Altamore, L.; Ingrassia, M. Quality factors influencing consumer demand for small fruit by focus group and sensory test. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; McKenna, K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods 2017, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdicca, R.; Paolanti, M.; Frontoni, E. eTourism: ICT and its role for tourism management. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.C.; Fortes, N.; Santiago, R. Influence of sensory stimuli on brand experience, brand equity and purchase intention. J. Bus. Econo. Manag. 2017, 18, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Nadal, E.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Sensory and Aroma Marketing; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Altamore, L.; Ingrassia, M.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S.; Bacarella, S. Italian Consumers’ Preferences for Pasta and Consumption Trends: Tradition or Innovation? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Lerro, M.; Chrysochou, P.; Vecchio, R.; Krystallis, A. One size does (obviously not) fit all: Using product attributes for wine market segmentation. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T.; Giancristofaro, R.A.; Corain, L.; Salmaso, L.; Tomasi, D.; Boatto, V. The importance of landscape in wine quality perception: An integrated approach using choice-based conjoint analysis and combination-based permutation tests. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Schimmenti, E.; Campolo, M.G.; Giannetto, C. The willingness to pay of Sicilian consumer for a wine obtained with sustainable production method: An estimate through an ordered probit sample-selection model. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Group | Participants (n) | Gender and Age Range | Competences and Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | Seven females, five males; age range 25–35 years old | Wine influencer; Wine blogger; Web designer of wineries and wine events; Researcher in Communication sciences; Oenologist with experience in Etna DOC1 wine |

| 2 | 12 | Six females, six males; age range 35–45 years old | Food and wine journalist; Marketing manager with experience in territorial politics; Journalist expert in web communication; Researcher in communication sciences; Researcher in wine marketing and communication |

| 3 | 12 | Five females, six males; age range 45–65 years old | Wine marketing manager with experience in heroic wines; Wine marketing manager with experience in territorial politics; President of the “Strada del Vino Etna DOC”; Associate professor of wine marketing and communication; Full professor of wine economics and policies; President of the Italian Sommelier Association; Wine influencer |

| Phases 1 | Focus Group 1 (12 Participants: 6 Women and 6 Men) | Focus Group 2 (12 Participants: 5 Women and 7 Men) | Focus Group 3 (12 Participants: 7 Women and 5 Men) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operations | Outputs | Operations | Outputs | Operations | Outputs | |

| Phase 1 (after 4 months) | 4 months of individual website observation, followed by the first meeting of Focus group 1 | Personal judgements of experts on websites and discussion of Focus group 1 on identified topics | 4 months of individual website observation, followed by the first meeting of focus group 2 | Personal judgements of experts on websites and discussion of Focus group 2 on identified topics | 4 months of individual website observation, followed by the first meeting of Focus group 3 | Personal judgements of experts on websites and discussion of Focus group 3 on identified topics |

| Phase 2 (after 8 months) | 4 months of individual observation of the websites, followed by the second meeting of Focus group 1 | Personal judgements on websites and Focus group 1 discussion on identified topics | 4 months of individual observation of the websites, followed by the second meeting of focus group 2 | Personal judgements on websites and Focus group 2 discussion on identified topics | 4 months of individual observation of the websites, followed by the second meeting of Focus group 3 | Personal judgements on websites and Focus group 3 discussion on identified topics |

| Phase 3 (after 12 months) | 4 months of individual observation of the websites, followed by the third meeting of Focus group 1 | Final discussion of Focus group 1 on the identified topics and scoring of each website (for all indicators of the scheme) | 4 months of individual observation of the websites, followed by the third meeting of focus group 2 | Final discussion of Focus group 2 on the identified topics and scoring of each website (for all indicators of the scheme) | 4 months of individual observation of the websites, followed by the third meeting of Focus group 3 | Final discussion of Focus group 3 on the identified topics and scoring of each website (for all indicators of the scheme) |

| Dimension | Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Adaption | 1 | Site design | Quality of site design | From 0 to 5 |

| 2 | Ease of access and browsing | Ease of navigation on the website | From 0 to 5 | |

| 3 | Quality of images | Quality characteristics of pictures of the territory | From 0 to 5 | |

| G-Goal attainment | 1 | Information provided | Quantity of information about the link with the Etna Mountain territory | From 0 to 5 |

| 2 | Thematic areas | Quantity of touristic information, i.e., information and other activities linked to the territory (culture, wine & food activities, nature, sport, art, folklore, etc.) | From 0 to 5 | |

| 3 | Pictures of the territory | Number of pictures evoking (linking with) the Etna Mountain territory | From 0 to 5 | |

| I-Integration | 1 | Communication style of the website’s reception | Communication style | From 0 to 5 |

| 2 | International profile | Number of foreign languages used | From 0 to 5 | |

| 3 | Interactivity of website | Chat rooms, forums, social networks | From 0 to 5 | |

| L-Latent pattern maintenance | 1 | Identity | Distinctiveness of the website | From 0 to 5 |

| 2 | Originality/innovation | Originality and innovation of the website structure | From 0 to 5 | |

| 3 | Coherence/consistency | Coherence of communication (images, language, contents, text, immediacy of the comprehensibility of the message, evocation of the territory) | From 0 to 5 | |

| Scoring Band on a 1–10 Scales | Scoring Band Obtained | Assigned Level of Communicativeness | Percentage of Wineries Belonging to This Group | Number of Wineries Belonging to This Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9–10 | 52–55 | Excellent | 8% | 3 |

| 7–8 | 40–50 | Good | 32% | 12 |

| 5–6 | 30–39 | Acceptable | 26% | 10 |

| 3–4 | 21–27 | Poor | 24% | 9 |

| 1–2 | 15–20 | None | 10% | 4 |

| Scoring Band on a 1–10 Scales | Scoring Band Obtained | Assigned Level of Communicativeness | Percentage of Wineries Belonging to This Group | Number of Wineries Belonging to This Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9–10 | 52–55 | Excellent | 13% | 5 |

| 7–8 | 40–50 | Good | 24% | 9 |

| 5–6 | 30–39 | Acceptable | 37% | 14 |

| 3–4 | 21–27 | Poor | 26% | 26 |

| Scoring Band on a 1–10 Scales | Scoring Band Obtained | Assigned Level of Communicativeness | Percentage of Wineries Belonging to This Group | Number of Wineries Belonging to This Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9–10 | 52–55 | Excellent | 3% | 1 |

| 7–8 | 40–50 | Good | 47% | 18 |

| 5–6 | 30–39 | Acceptable | 42% | 16 |

| 3–4 | 21–27 | Poor | 8% | 3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chironi, S.; Altamore, L.; Columba, P.; Bacarella, S.; Ingrassia, M. Study of Wine Producers’ Marketing Communication in Extreme Territories–Application of the AGIL Scheme to Wineries’ Website Features. Agronomy 2020, 10, 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10050721

Chironi S, Altamore L, Columba P, Bacarella S, Ingrassia M. Study of Wine Producers’ Marketing Communication in Extreme Territories–Application of the AGIL Scheme to Wineries’ Website Features. Agronomy. 2020; 10(5):721. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10050721

Chicago/Turabian StyleChironi, Stefania, Luca Altamore, Pietro Columba, Simona Bacarella, and Marzia Ingrassia. 2020. "Study of Wine Producers’ Marketing Communication in Extreme Territories–Application of the AGIL Scheme to Wineries’ Website Features" Agronomy 10, no. 5: 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10050721

APA StyleChironi, S., Altamore, L., Columba, P., Bacarella, S., & Ingrassia, M. (2020). Study of Wine Producers’ Marketing Communication in Extreme Territories–Application of the AGIL Scheme to Wineries’ Website Features. Agronomy, 10(5), 721. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10050721