Enhancing Processability and Multifunctional Properties of Polylactic Acid–Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Composites with Cellulose Nanocrystals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Composites

2.3. Preparation of Test Samples

2.4. Characterisation Methods

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy

2.4.3. Electrical Conductivity

2.4.4. Thermal Conductivity

2.4.5. Rheological Measurements

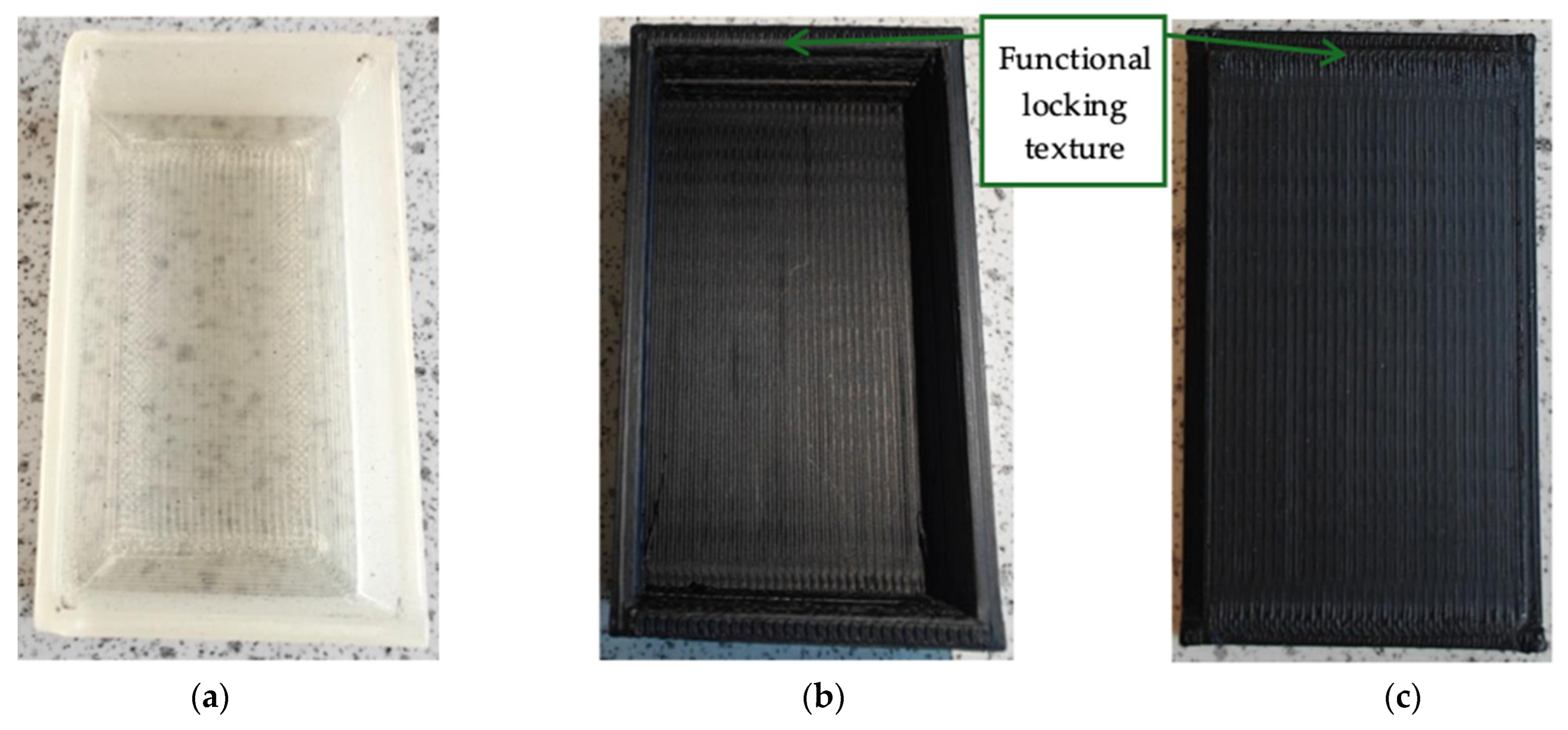

2.5. Prototyping Using Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) 3D Printing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Production of PLA and PLA-Based Composite Filaments

3.2. Structure and Morphology

3.3. Electrical Conductivity

3.4. Thermal Conductivity

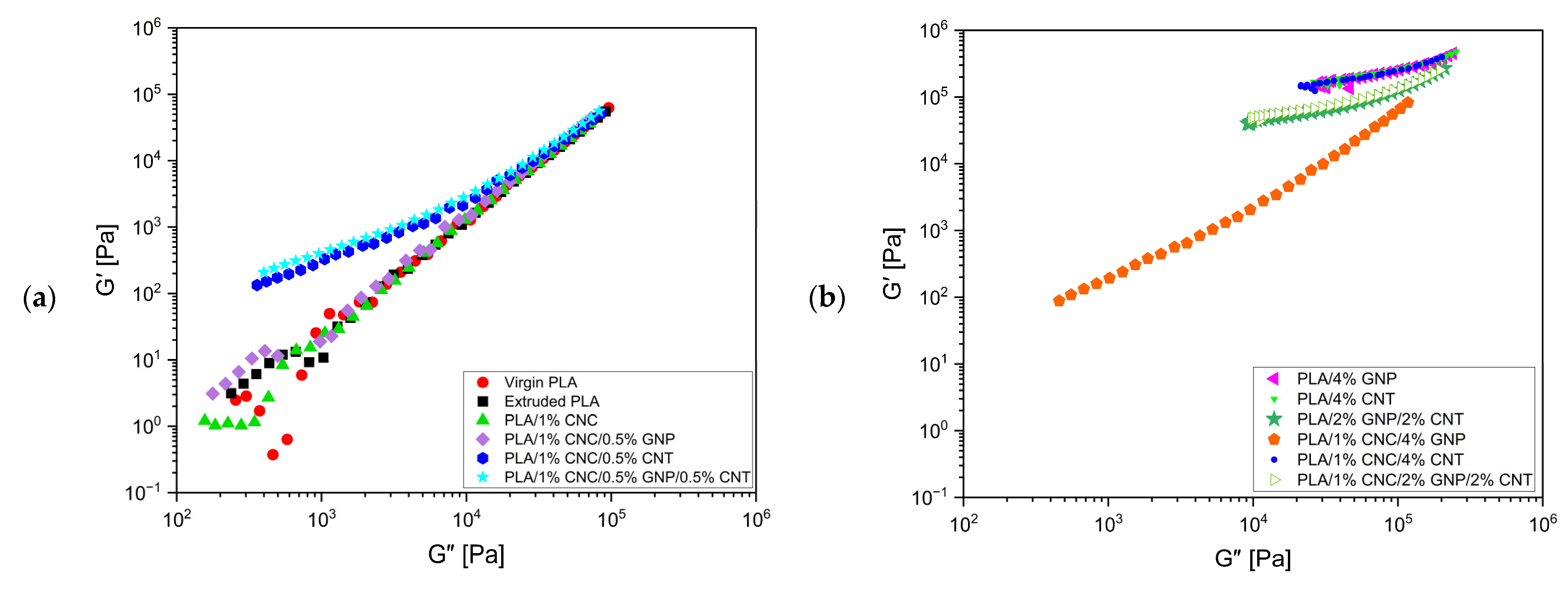

3.5. Rheological Properties

3.6. Correlation Between Structure and Multifunctional Properties

3.7. Comparison of Results with Literature and Prototyping

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CB | Carbon black |

| CNC | Cellulose nanocrystal |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| EHP | Electrically heated parallel plate |

| FDM | Fused deposition modelling |

| GNP | Graphene nanoplatelet |

| hBN | Hexagonal boron nitride |

| LVR | Linear viscoelastic region |

| PLA | Poly(lactic acid) |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscope |

| A | Cross-sectional area of filament |

| Specific heat capacity | |

| Cohesive energy density | |

| G’ | Storage modulus |

| Average storage modulus within the LVR | |

| G” | Loss modulus |

| L | Length |

| R | Electrical resistance |

| Thermal diffusivity | |

| Absolute strain | |

| Critical strain | |

| Complex viscosity | |

| Electrical conductivity | |

| Thermal conductivity | |

| Bulk density | |

| Elastic stress | |

| Angular frequency |

References

- Namazi, H. Polymers in Our Daily Life. Bioimpacts 2017, 7, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Matuana, L.M. Surface Texture and Barrier Performance of Poly(Lactic Acid)–Cellulose Nanocrystal Extruded-Cast Films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Panda, P.; Jebastine, J.; Ramarao, M.; Fairooz, S.; Reddy, C.K.; Nasif, O.; Alfarraj, S.; Manikandan, V.; Jenish, I. Exploration on Mechanical Behaviours of Hyacinth Fibre Particles Reinforced Polymer Matrix-Based Hybrid Composites for Electronic Applications. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 4933450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentano, I.; Bitinis, N.; Fortunati, E.; Mattioli, S.; Rescignano, N.; Verdejo, R.; Lopez-Manchado, M.A.; Kenny, J.M. Multifunctional Nanostructured PLA Materials for Packaging and Tissue Engineering. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1720–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Wei, Z.; Mo, Q.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, Y.; Huang, C.; et al. Research Progress in Polylactic Acid Processing for 3D Printing. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 112, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.; Gonçalves, I.C.; Magalhães, F.D.; Pinto, A.M. Poly(Lactic Acid) Composites Containing Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: A Review. Polymers 2017, 9, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasprilla, A.J.R.; Martinez, G.A.R.; Lunelli, B.H.; Jardini, A.L.; Filho, R.M. Poly-Lactic Acid Synthesis for Application in Biomedical Devices—A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboulsi, N.; Majid, F.; Louzazni, M. Environmentally Friendly PLA-Based Conductive Composites: Electrical and Mechanical Performance. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eynde, M.; Van Puyvelde, P. 3D Printing of Poly(Lactic Acid). In Industrial Applications of Poly(Lactic Acid); Di Lorenzo, M.L., Androsch, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Grau, S.; Lazaro-Hdez, C.; Pascual, J.; Fenollar, O.; Boronat, T. Enhancing Polylactic Acid Properties with Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Black Nanoparticles: A Study of the Electrical and Mechanical Characterization of 3D-Printed and Injection-Molded Samples. Polymers 2024, 16, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Radecka, I.; Eissa, A.M.; Ivanov, E.; Stoeva, Z.; Tchuenbou-Magaia, F. Recent Advances in Carbon-Based Sensors for Food and Medical Packaging Under Transit: A Focus on Humidity, Temperature, Mechanical, and Multifunctional Sensing Technologies—A Systematic Review. Materials 2025, 18, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, B.; Cappetti, N.; Di Maio, L.; Scarfato, P.; Incarnato, L. 3D Printing of PLA/Clay Nanocomposites: Influence of Printing Temperature on Printed Samples Properties. Materials 2018, 11, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueira, D.; Holmen, S.; Melbø, J.K.; Moldes, D.; Echtermeyer, A.T.; Chinga-Carrasco, G. Enzymatic-Assisted Modification of Thermomechanical Pulp Fibers to Improve the Interfacial Adhesion with Poly(Lactic Acid) for 3D Printing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9338–9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiao, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, F.; Luo, B.; Huang, S.; Shang, Y.; Wen, H.; Christiansen, J.D.C.; et al. Crystalline Structures and Crystallization Behaviors of Poly(L-Lactide) in Poly(L-Lactide)/Graphene Nanosheet Composites. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 3988–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, N.; Jawaid, M.; Al-Othman, O. An Overview on Polylactic Acid, Its Cellulosic Composites and Applications. Curr. Org. Synth. 2017, 14, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, W.; Yee, K.; Lee, K.-Y.; Tagarielli, V.L. Measurements of the Mechanical Response of Unidirectional 3D-Printed PLA. Mater. Des. 2017, 123, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeluga, U.; Kumanek, B.; Trzebicka, B. Synergy in Hybrid Polymer/Nanocarbon Composites. A Review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 73, 204–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Ahn, S.J.; Choi, H.J. Melt Rheology and Mechanical Characteristics of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Alkylated Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites. Polymers 2020, 12, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalal Uddin, A.; Araki, J.; Gotoh, Y. Toward “Strong” Green Nanocomposites: Polyvinyl Alcohol Reinforced with Extremely Oriented Cellulose Whiskers. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Banerjee, S.; Roy, P.; Pal, K. Melt-blending of Unmodified and Modified Cellulose Nanocrystals with Reduced Graphene Oxide into PLA Matrix for Biomedical Application. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 3049–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakahara, R.M.; Da Silva, D.J.; Wang, S.H. Composites of ABS with SEBS-g-MA and Copper Microparticles Modified by Mussel-Bioinspired Polydopamine: A Comparative Rheological Study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Gaur, S.S.; Soundararajan, N.; Gupta, A.; Bhasney, S.M.; Milli, M.; Kumar, A.; Katiyar, V. Reactive Extrusion of Polylactic Acid/Cellulose Nanocrystal Films for Food Packaging Applications: Influence of Filler Type on Thermomechanical, Rheological, and Barrier Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 4718–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, E.; Kotsilkova, R.; Xia, H.; Chen, Y.; Donato, R.K.; Donato, K.; Godoy, A.P.; Di Maio, R.; Silvestre, C.; Cimmino, S.; et al. PLA/Graphene/MWCNT Composites with Improved Electrical and Thermal Properties Suitable for FDM 3D Printing Applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, G.; Guarini, R.; Kotsilkova, R.; Ivanov, E.; Romano, V. Experimental, Theoretical and Simulation Studies on the Thermal Behavior of PLA-Based Nanocomposites Reinforced with Different Carbonaceous Fillers. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, G.; Lamberti, P.; Tucci, V.; Kotsilkova, R.; Ivanov, E.; Menseidov, D.; Naddeo, C.; Romano, V.; Guadagno, L.; Adami, R.; et al. Nanocarbon/Poly(Lactic) Acid for 3D Printing: Effect of Fillers Content on Electromagnetic and Thermal Properties. Materials 2019, 12, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinelli, G.; Kotsilkova, R.; Ivanov, E.; Petrova-Doycheva, I.; Menseidov, D.; Georgiev, V.; Di Maio, R.; Silvestre, C. Effects of Filament Extrusion, 3D Printing and Hot-Pressing on Electrical and Tensile Properties of Poly(Lactic) Acid Composites Filled with Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene. Nanomaterials 2019, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, P.; Spinelli, G.; Kuzhir, P.P.; Guadagno, L.; Naddeo, C.; Romano, V.; Kotsilkova, R.; Angelova, P.; Georgiev, V. Evaluation of Thermal and Electrical Conductivity of Carbon-Based PLA Nanocomposites for 3D Printing. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1981, 020158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, R.; Kotsilkova, R. Influence of Graphene Nanoplates and Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes on Rheology, Structure, and Properties Relationship of Poly (Lactic Acid). J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2021, 51, 317–334. [Google Scholar]

- Mármol, G.; Sanivada, U.K.; Fangueiro, R. Effect of GNPs on the Piezoresistive, Electrical and Mechanical Properties of PHA and PLA Films. Fibers 2021, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Tsou, C.-H.; Yu, Y.; Wu, C.-S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, T.; Ge, F.; Liu, P.; Guzman, M.R.D. Conductivity and Mechanical Properties of Carbon Black-Reinforced Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA/CB) Composites. Iran. Polym. J. 2021, 30, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xin, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, B.; Feng, X.; Mao, Z.; Sui, X. Poly(Lactic Acid)/Carbon Nanotube Composites with Enhanced Electrical Conductivity via a Two-Step Dispersion Strategy. Compos. Commun. 2022, 30, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosanenzadeh, S.G.; Khalid, S.; Cui, Y.; Naguib, H.E. High Thermally Conductive PLA Based Composites with Tailored Hybrid Network of Hexagonal Boron Nitride and Graphene Nanoplatelets. Polym. Compos. 2016, 37, 2196–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsilkova, R.; Georgiev, V.; Aleksandrova, M.; Batakliev, T.; Ivanov, E.; Spinelli, G.; Tomov, R.; Tsanev, T. Improving Resistive Heating, Electrical and Thermal Properties of Graphene-Based Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride) Nanocomposites by Controlled 3D Printing. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, E.; Kotsilkova, R.; Georgiev, V.; Batakliev, T.; Angelov, V. Advanced Rheological, Dynamic Mechanical and Thermal Characterization of Phase-Separation Behavior of PLA/PCL Blends. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzawi, M.K.; Rohn, C.L.; Beyoglu, B.; Haber, R.A. Rheological Assessment of Cohesive Energy Density of Highly Concentrated Stereolithography Suspensions. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 8473–8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakahara, R.; da Silva, D.J.; Wang, S.H. Melt Flow Characterization of Highly Loaded Cooper Filled Poly(Acrylonitrile-Co-Butadiene-Co-Styrene). Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 277, 111392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, S.; Etxeberria, A.; Mocholi, V.; Rekondo, A.; Grande, H.; Labidi, J. Effect of Combining Cellulose Nanocrystals and Graphene Nanoplatelets on the Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Based Films. Express Polym. Lett. 2018, 12, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.D.; Kusmono; Wildan, M.W. Herianto Preparation and Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystals-Reinforced Poly (Lactic Acid) Composite Filaments for 3D Printing Applications. Results Eng. 2023, 17, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsilkova, R.; Ivanov, E.; Georgiev, V.; Ivanova, R.; Menseidov, D.; Batakliev, T.; Angelov, V.; Xia, H.; Chen, Y.; Bychanok, D.; et al. Essential Nanostructure Parameters to Govern Reinforcement and Functionality of Poly(Lactic) Acid Nanocomposites with Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes for 3D Printing Application. Polymers 2020, 12, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Lavorgna, M.; Ronca, A.; Fei, G.; Xia, H. Simultaneous Realization of Conductive Segregation Network Microstructure and Minimal Surface Porous Macrostructure by SLS 3D Printing. Mater. Des. 2019, 178, 107874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achaby, M.; Arrakhiz, F.; Vaudreuil, S.; El Kacem Qaiss, A.; Bousmina, M.; Fassi-Fehri, O. Mechanical, Thermal, and Rheological Properties of Graphene-based Polypropylene Nanocomposites Prepared by Melt Mixing. Polym. Compos. 2012, 33, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Picot, O.T.; Bilotti, E.; Peijs, T. Influence of Filler Size on the Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA)/Graphene Nanoplatelet (GNP) Nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 86, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, S.; Gupta, R.K.; Baum, T.; Kao, N.; Bhattacharya, S.N. Morphology, Electromagnetic Properties and Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Performance of Poly Lactide/Graphene Nanoplatelet Nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2016, 95, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jeong, Y.G. Polylactide/Exfoliated Graphite Nanocomposites with Enhanced Thermal Stability, Mechanical Modulus, and Electrical Conductivity. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2010, 48, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Guerraf, A.; Ziani, I.; Ben Jadi, S.; El Bachiri, A.; Bazzaoui, M.; Bazzaoui, E.A.; Sher, F. Smart Conducting Polymer Innovations for Sustainable and Safe Food Packaging Technologies. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2024, 23, e70045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.J.; Azevedo, A.M.D.; Monteiro, S.N.; Araujo-Moreira, F.M. Electrical Properties of Composite Materials: A Comprehensive Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wan, Q.; Gao, J. Recent Development of Conductive Polymer Composite-based Strain Sensors. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 3167–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Jia, W.; Feng, X.; Yang, H.; Xie, Y.; Shang, J.; Wang, P.; Guo, Y.; Li, R.-W. Flexible Sensors Based on Conductive Polymer Composites. Sensors 2024, 24, 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, C.L.; Chen, F.C.; Luk, W.H. Thermal Conductivity of Oriented Crystalline Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. Ed. 1980, 18, 1187–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, C.L.; Greig, D. The Low-Temperature Thermal Conductivity of a Semi-Crystalline Polymer, Polyethylene Terephthalate. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1975, 8, 3121–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossinsky, E.; Müller-Plathe, F. Anisotropy of the Thermal Conductivity in a Crystalline Polymer: Reverse Nonequilibrium Molecular Dynamics Simulation of the δ Phase of Syndiotactic Polystyrene. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 134905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Zhang, Y. Thermal Conductive Polymer Composites: Recent Progress and Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Z.; Luo, T. Thermal Transport in Polymers: A Review. J. Heat. Transf. 2021, 143, 072101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, S.H. Nano-Bridge Effect on Thermal Conductivity of Hybrid Polymer Composites Incorporating 1D and 2D Nanocarbon Fillers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 222, 109072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, L.; Scaffaro, R.; Sutera, F.; Mistretta, M.C. Reprocessing of PLA/Graphene Nanoplatelets Nanocomposites. Polymers 2018, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Fonseca, A.A.; González-López, M.E.; Robledo-Ortíz, J.R. Reprocessing and Recycling of Poly(Lactic Acid): A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 4143–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezger, T. The Rheology Handbook—For Users of Rotational and Oscillatory Rheometers. Appl. Rheol. 2002, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileo, P.G.M.; Krauter, C.M.; Sanders, J.M.; Browning, A.R.; Halls, M.D. Molecular-Scale Exploration of Mechanical Properties and Interactions of Poly(Lactic Acid) with Cellulose and Chitin. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 42417–42428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, F.W.; Schrøder, T.B.; Glotzer, S.C. Effects of a Nanoscopic Filler on the Structure and Dynamics of a Simulated Polymer Melt and the Relationship to Ultrathin Films. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 021802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penu, C.; Hu, G.-H.; Fernandez, A.; Marchal, P.; Choplin, L. Rheological and Electrical Percolation Thresholds of Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Nanocomposites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2012, 52, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsilkova, R.; Tabakova, S.; Ivanova, R. Effect of Graphene Nanoplatelets and Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes on the Viscous and Viscoelastic Properties and Printability of Polylactide Nanocomposites. Mech. Time-Depend. Mater. 2022, 26, 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, S.; Gupta, R.K.; Baum, T.; Kao, N.; Bhattacharya, S.N. Phase Transition and Anomalous Rheological Behaviour of Polylactide/Graphene Nanocomposites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 135, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, G.; Lamberti, P.; Tucci, V.; Ivanova, R.; Tabakova, S.; Ivanov, E.; Kotsilkova, R.; Cimmino, S.; Di Maio, R.; Silvestre, C. Rheological and Electrical Behaviour of Nanocarbon/Poly(Lactic) Acid for 3D Printing Applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 167, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Electrical Conductivity (S/m) | Thermal Conductivity (W/mK) | Critical Strain (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 0.183 | — | [25,27] | |

| PLA/1.5% GNP | — | — | [25] | |

| PLA/3% GNP | 0.323 | — | ||

| PLA/6% GNP | 0.448 | — | ||

| PLA/9% GNP | 0.550 | — | ||

| PLA/12% GNP | 6.27 | 0.664 | — | |

| PLA/1.5% CNT | — | — | ||

| PLA/3% CNT | 0.231 | — | ||

| PLA/6% CNT | 0.232 | — | ||

| PLA/9% CNT | 0.268 | — | ||

| PLA/12% CNT | 4.54 | 0.365 | — | |

| PLA/3% GNP/3% CNT | 0.270 | — | ||

| PLA/6% GNP/6% CNT | 0.352 | — | ||

| PLA/12% GNP/12% CNT | 0.533 | — | ||

| PLA/12% GNPs | 6.27 | 0.676 | — | [27] |

| PLA/12% CNT | 4.54 | 0.334 | — | |

| PLA/6% GNP | 0.577 | 0.09 | [23,28] | |

| PLA/6% CNT | 0.303 | — | ||

| PLA/1.5% GNP/1.5% CNT | 0.3013 | — | ||

| PLA/1.5% GNP/4.5% CNT | 0.3779 | 0.32 | ||

| PLA/3% GNP/3% CNT | 0.4253 | 0.30 | ||

| PLA/4.5% GNP/1.5% CNT | 0.4692 | 0.25 | ||

| PLA/3% GNP | — | — | [29] | |

| PLA/7.5% GNP | 0.20 | — | — | |

| PLA/1% CNC/15% GNP | 5.59 | — | — | |

| PLA/4% CB | 0.6 | — | — | [30] |

| PLA/20% CB | 14.3 | — | — | |

| PLA/5.6% CNT | 72.2 | — | — | [31] |

| PLA/33.3 vol%(GNP/hBN)(50 GNP:50 hBN) | 2.77 | — | [32] | |

| PLA/4% GNP | 0.200 | 5.72 | This work | |

| PLA/4% CNT | 30.70 | 0.226 | 1.04 | |

| PLA/2% GNP/2% CNT | 0.16 | 0.228 | 1.14 | |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% GNP | 0.211 | 12.66 | ||

| PLA/1% CNC/4% CNT | 38.30 | 0.245 | 0.51 | |

| PLA/1% CNC/2% GNP/2% CNT | 1.27 | 0.279 | 1.27 |

| Composition Code (wt%) | PLA Content (wt%) | CNC Content (wt%) | GNP Content (wt%) | CNT Content (wt%) | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA | 100 | - | - | - | Reference |

| PLA/1% CNC | 99 | 1 | - | - | Mono-filler (CNC) |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% GNP | 98.5 | 1 | 0.5 | - | Bi-filler (CNC + GNP) |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% CNT | 98.5 | 1 | - | 0.5 | Bi-filler (CNC + CNT) |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% GNP/0.5% CNT | 98 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | Tri-filler (CNC + GNP + CNT) |

| PLA/4% GNP | 96 | - | 4 | - | Mono-filler (GNP) |

| PLA/4% CNT | 96 | - | - | 4 | Mono-filler (CNT) |

| PLA/2% GNP/2% CNT | 96 | - | 2 | 2 | Bi-filler (GNP + CNT) |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% GNP | 95 | 1 | 4 | - | Bi-filler (CNC + GNP) |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% CNT | 95 | 1 | - | 4 | Bi-filler (CNC + CNT) |

| PLA/1% CNC/2% GNP/2% CNT | 95 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Tri-filler (CNC + GNP + CNT) |

| Composition Code (wt%) | Electrical Conductivity (S/m) |

|---|---|

| PLA | — |

| PLA/1% CNC | — |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% GNP | |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% CNT | |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% GNP/0.5% CNT | |

| PLA/4% GNP | |

| PLA/4% CNT | 30.70 ± 2.1 |

| PLA/2% GNP/2% CNT | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% GNP | |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% CNT | 38.30 ± 0.67 |

| PLA/1% CNC/2% GNP/2% CNT | 1.27 ± 0.24 |

| Materials | Tonset (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin PLA | 341.10 | 361.22 | 58.72 | 154.08 |

| Extruded PLA | 341.34 | 359.77 | 57.48 | 150.94 |

| Composition Code (wt%) | Yield Stress (Pa) | Yield Strain (-) | (%) | (Pa) | (J/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin PLA | 2571.88 | 2.07 | 63.34 | 2427.87 | 487.05 |

| Extruded PLA | 2299.64 | 2.36 | 63.32 | 1923.87 | 385.68 |

| PLA/1% CNC | 1057.78 | 2.60 | 79.59 | 753.20 | 238.58 |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% GNP | 1709.54 | 2.07 | 63.32 | 1482.19 | 297.15 |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% CNT | 1680.80 | 1.86 | 7.98 | 2898.19 | 9.22 |

| PLA/1% CNC/0.5% GNP/0.5% CNT | 1707.11 | 1.65 | 7.95 | 4029.43 | 12.74 |

| PLA/4% GNP | 9085.03 | 1.69 | 5.72 | 22,089.56 | 35.77 |

| PLA/4% CNT | 16,924.93 | 0.76 | 1.04 | 226,452.63 | 12.18 |

| PLA/2% GNP/2% CNT | 10,384.81 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 78,757.90 | 5.20 |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% GNP | 2163.85 | 1.86 | 12.66 | 3311.70 | 26.54 |

| PLA/1% CNC/4% CNT | 15,334.67 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 235,215.63 | 3.04 |

| PLA/1% CNC/2% GNP/2% CNT | 9199.63 | 1.06 | 1.27 | 78,674.00 | 6.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, S.; Ivanov, E.; Georgiev, V.; Stanley, P.; Radecka, I.; Eissa, A.M.; Tolve, R.; Tchuenbou-Magaia, F. Enhancing Processability and Multifunctional Properties of Polylactic Acid–Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Composites with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Polymers 2026, 18, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010099

Guo S, Ivanov E, Georgiev V, Stanley P, Radecka I, Eissa AM, Tolve R, Tchuenbou-Magaia F. Enhancing Processability and Multifunctional Properties of Polylactic Acid–Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Composites with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Siting, Evgeni Ivanov, Vladimir Georgiev, Paul Stanley, Iza Radecka, Ahmed M. Eissa, Roberta Tolve, and Fideline Tchuenbou-Magaia. 2026. "Enhancing Processability and Multifunctional Properties of Polylactic Acid–Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Composites with Cellulose Nanocrystals" Polymers 18, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010099

APA StyleGuo, S., Ivanov, E., Georgiev, V., Stanley, P., Radecka, I., Eissa, A. M., Tolve, R., & Tchuenbou-Magaia, F. (2026). Enhancing Processability and Multifunctional Properties of Polylactic Acid–Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Composites with Cellulose Nanocrystals. Polymers, 18(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010099