Fermentation of Lignocellulosic Substrates Enhances the Safety and Nutritional Quality of Flake Soil for Rhinoceros Beetle Rearing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Raw Materials

2.2. Flake Soil Preparation and Fermentation Process

2.3. Sample Collection for Analysis

2.4. Characterization of Flake Soil Properties

2.5. DNA Sample Preparation of Flake Soil Microbiota

2.6. 16S Metagenomic Library Preparation

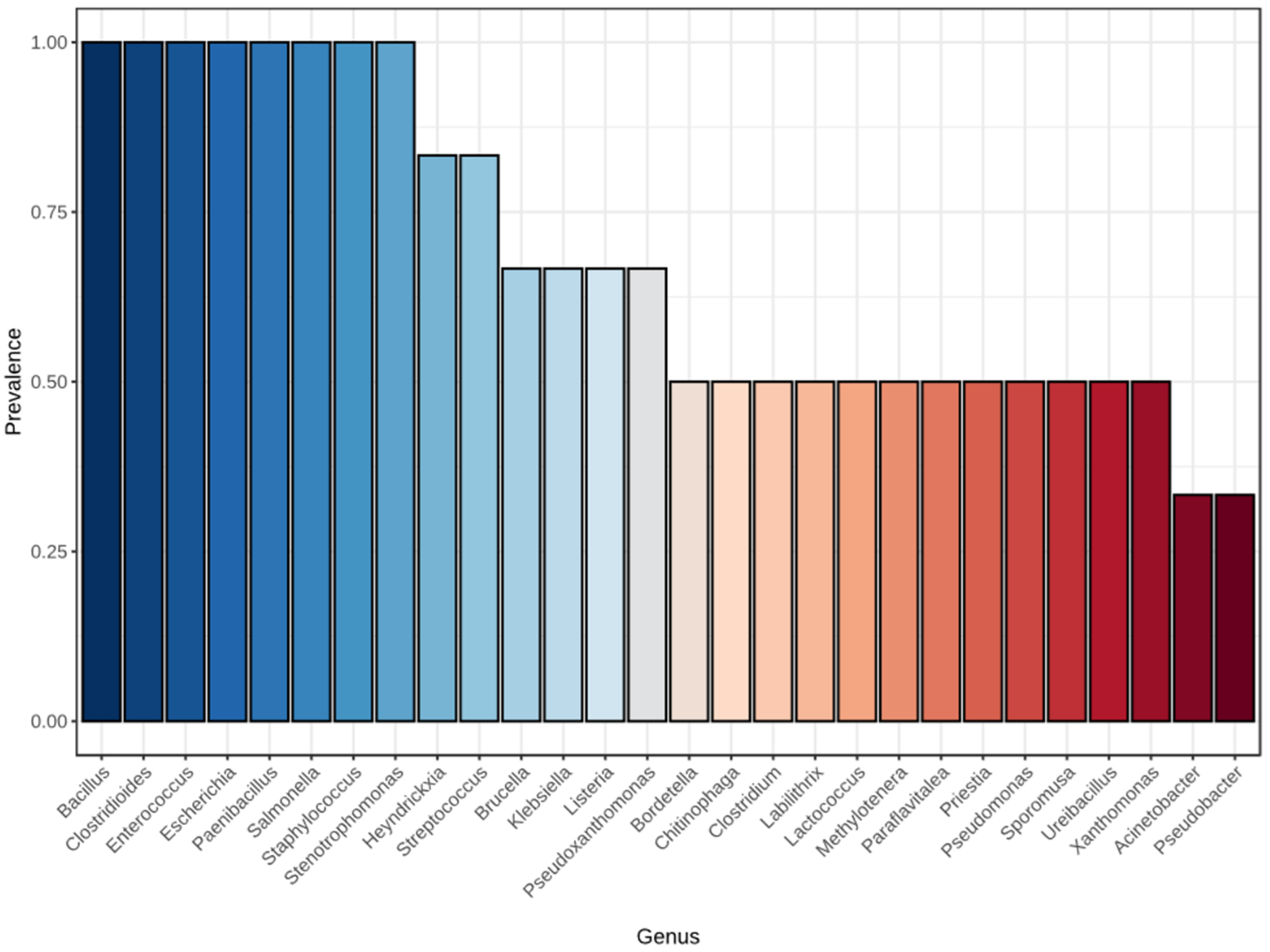

2.7. Nanopore Sequencing and Data Analysis

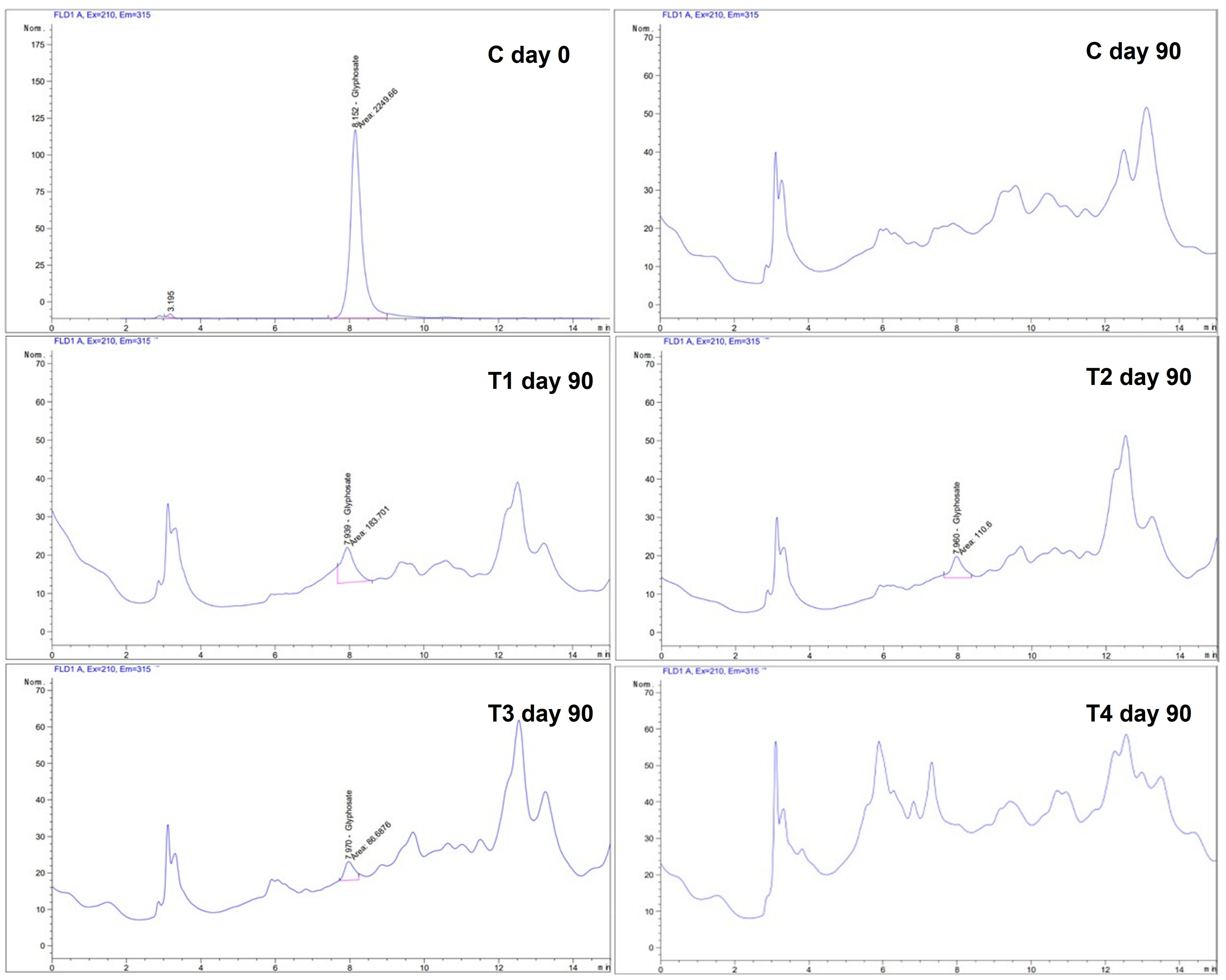

2.8. Glyphosate Residues in Fermented Flake Soil

2.9. Statistical Analysis

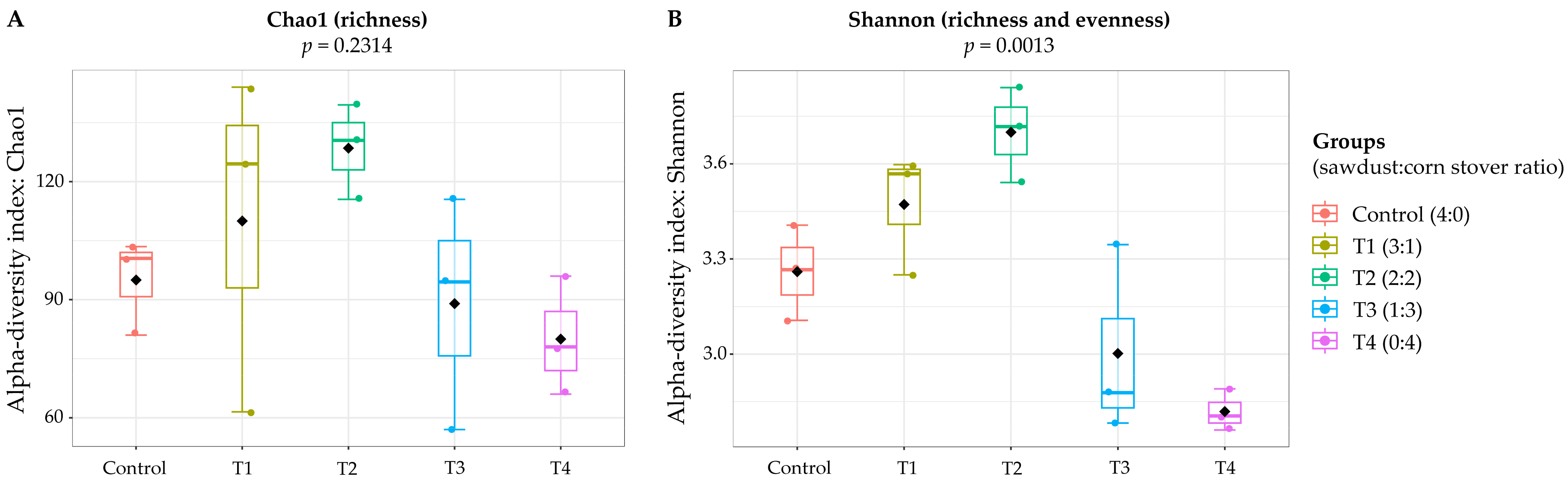

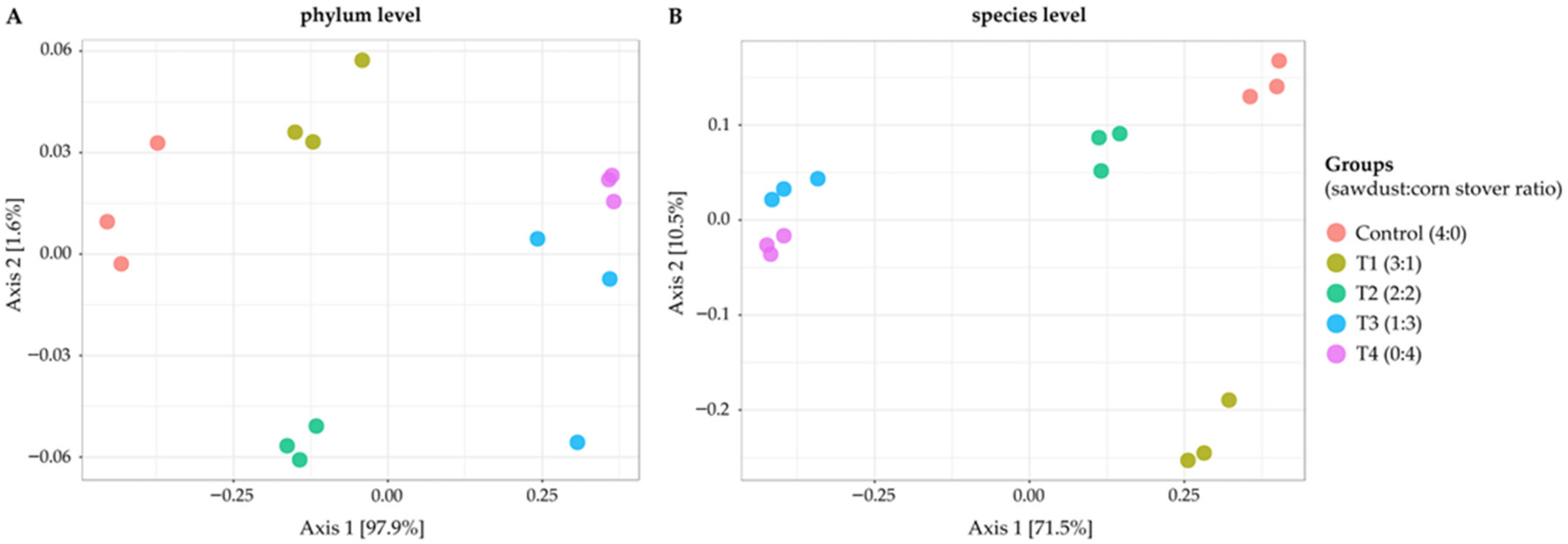

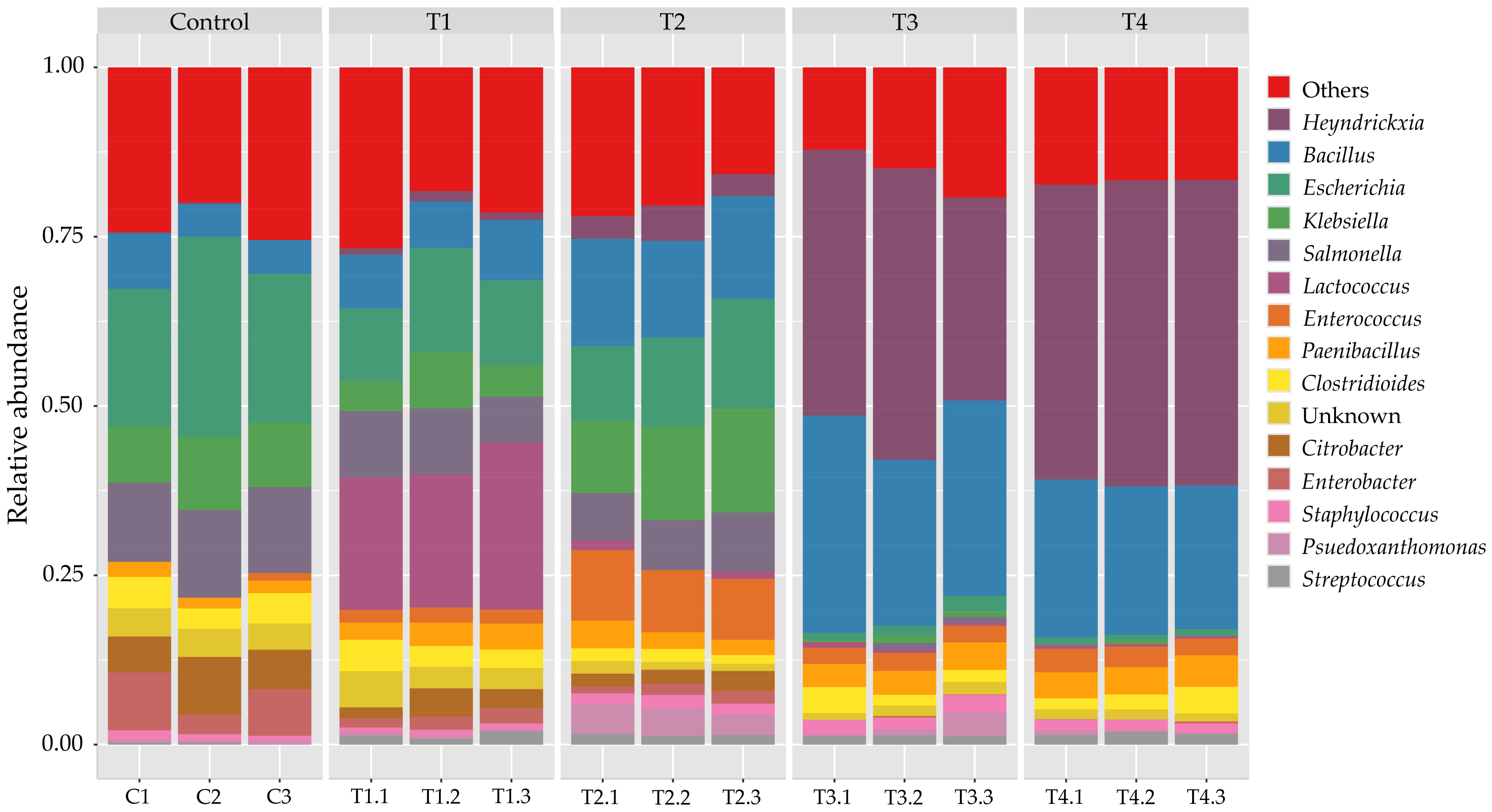

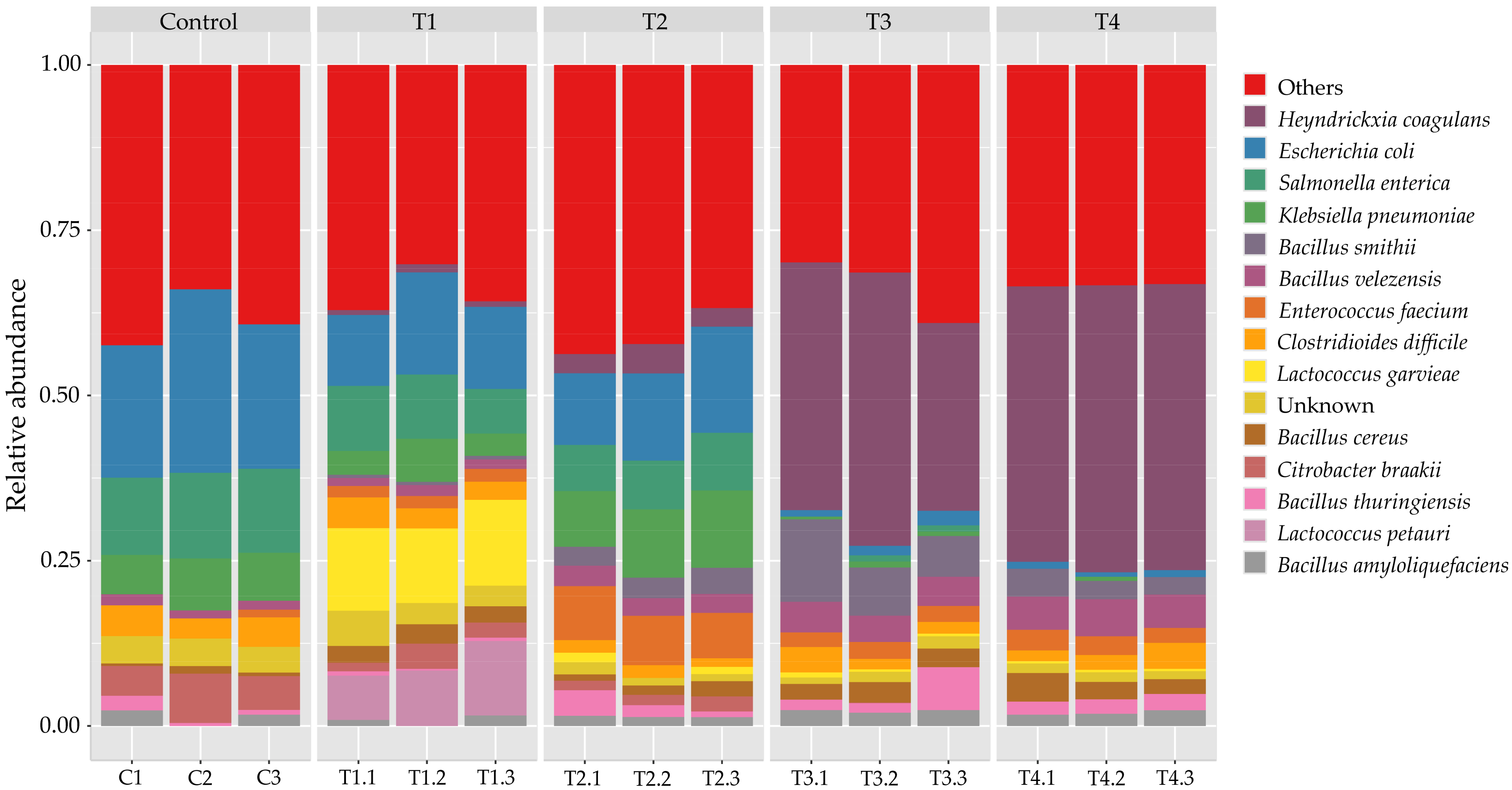

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Collaboration |

| GC-FID | Gas chromatography with flame ionization detector |

| FAMEs | Fatty acid methyl esters |

| FMOC-Cl | 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate |

| EAAs | Essential amino acid |

| NAAs | Non-essential amino acids |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

References

- Rennesson, S.; Grimaud, E.; Césard, N. Insect magnetism: The communication circuits of Rhinoceros beetle fighting in Thailand. HAU J. Ethnogr. Theory 2012, 2, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.-J.; Cheng, C.-H.; Yeh, T.-F.; Pauchet, Y.; Shelomi, M. Coconut rhinoceros beetle digestive symbiosis with potential plant cell wall degrading microbes. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Weng, L.; Zhang, X.; Long, K.; An, X.; Bao, J.; Wu, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S. Trypoxylus dichotomus gut bacteria provides an effective system for bamboo lignocellulose degradation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02147-02122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhuang, T.; Hu, M.; Liu, S.; Wu, D.; Ji, B. Gut microbiota contributes to lignocellulose deconstruction and nitrogen fixation of the larva of Apriona swainsoni. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1072893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seastedt, T.R.; Crossley, D.A. Soil Arthropods and Their Role in Decomposition and Mineralization Processes. In Forest Hydrology and Ecology at Coweeta; Swank, W.T., Crossley, D.A., Eds.; Springe: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, G. Observations on the biology of Xylotrupes gideon (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae) in Melanesia. Aust. J. Entomol. 1975, 14, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laruna, M.A.; Azman, E.A.; Ismail, R. Effect of rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros) larvae compost and vermicompost on selected soil chemical properties. World Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 7, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ambühl, D.G.J.; Bischof, T. Food from Wood; Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften, ZHAW, Institut für Umwelt und Natürliche Ressourcen, IUNR, Forschungsgruppe Phytomedizin: Wädenswil, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappini, E.; Molinari, P.; Busconi, M.; Callegari, M.; Fogher, C.; Bani, P. Hylotrupes bajulus (L.) (Col., Cerambycidae): Nutrition and attacked material. In Proceedings of the 10th International Working Conference on Stored Product Protection, Estoril, Portugal, 27 June—2 July 2010; pp. 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kartika, T.; Yoshimura, T. Evaluation of wood and cellulosic materials as fillers in artificial diets for Lyctus africanus Lesne (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae). Insects 2015, 6, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishanti, N.P.R.A.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Afifi, O.A.; Tarmadi, D.; Himmi, S.K.; Umezawa, T.; Ohmura, W.; Yoshimura, T. Effects of dietary variation on lignocellulose degradation and physiological properties of Nicobium hirtum larvae. J. Wood Sci. 2023, 69, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishanti, N.P.R.A.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Fujimoto, I.; Kartika, T.; Umezawa, T.; Hata, T.; Yoshimura, T. Structural basis of lignocellulose deconstruction by the wood-feeding anobiid beetle Nicobium hirtum. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanti, S.; Pizzo, B.; Feci, E.; Fiorentino, L.; Torniai, A.M. Nutritional requirements for larval development of the dry wood borer Trichoferus holosericeus (Rossi) in laboratory cultures. J. Pest Sci. 2010, 83, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmel, M.E.; Ding, S.-Y.; Johnson, D.K.; Adney, W.S.; Nimlos, M.R.; Brady, J.W.; Foust, T.D. Biomass recalcitrance: Engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science 2007, 315, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, K.; Rybarczyk, P.; Hołowacz, I.; Łukajtis, R.; Glinka, M.; Kamiński, M. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials as substrates for fermentation processes. Molecules 2018, 23, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, P.F.H.; Huijgen, W.; Bermudez, L.; Bakker, R. Literature Review of Physical and Chemical Pretreatment Processes for Lignocellulosic Biomass; Food & Biobased Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010; Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/150289 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Wongdao, S.; Black, R. Xylotrupes gideon eating bark of apple and pear trees in Northern Thailand. Trop. Pest Manag. 1987, 33, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, J.M. Male horn dimorphism, phylogeny and systematics of rhinoceros beetles of the genus Xylotrupes (Scarabaeidae: Coleoptera). Aust. J. Zool. 2003, 51, 213–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, T. Analysis of the structure and mechanism of wing folding and flexion in Xylotrupes gideon beetle (L. 1767) (Coloptera, Scarabaeidae). Acta Mech. Autom. 2012, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pradipta, A.P.; Wagiman, F.; Witjaksono, W. The coexistence of Oryctes rhinoceros L. and Xylotrupes gideon L. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) on immature plant in oil palm plantation. J. Perlindungan Tanam. Indones. 2020, 24, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livia, F.; Tjandrawinata, R.; Marpaung, C.D.; Pratiwi, D.; Komariah, K. The effect of horn beetle nano chitosan (Xylotrupes gideon) on the surface roughness of glass-ionomer cement. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2022, 1069, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiafe-Kwagyan, M.; Odamtten, G.T.; Kortei, N.K. Influence of substrate formulation on some morphometric characters and biological efficiency of Pleurotus ostreatus EM-1 (Ex. Fr) Kummer grown on rice wastes and “wawa” (Triplochiton scleroxylon) sawdust in Ghana. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Le Roux, S.; Ziebal, C.; Pinsard, G.; Sadet-Bourgeteau, S.; Oliva, A.; Piveteau, P. Soil-dependent fate of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Listeria monocytogenes after incorporation of digestates in soil microcosms. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 208, 105965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundharrajan, I.; Park, H.S.; Rengasamy, S.; Sivanesan, R.; Choi, K.C. Application and Future Prospective of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Natural Additives for Silage Production—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.; Gold, M.; Bosch, G.; Guillaume, J.; Rumbos, C.; El Deen, S.N.; Sandrock, C.; Oddon, S.B.; Athanassiou, C.; Cambra-Loópez, M. Bugbook: Nutritional requirements for edible insect rearing. J. Insects Food Feed 2025, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, X.B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.J.; Gao, Z.Z. Study on the Chemical Properties of Anthocephalus chinensis. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 518–523, 5366–5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer, G.W., Jr. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 19th ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC, 15th ed.; Methods 932.06, 925.09, 985.29, 923.03; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lepage, G.; Roy, C.C. Direct transesterification of all classes of lipids in a one-step reaction. J. Lipid Res. 1986, 27, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Jung, C. Nutritional value of bee-collected pollens of hardy kiwi, Actinidia arguta (Actinidiaceae) and oak, Quercus sp. (Fagaceae). J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Morales, J.B.; Cabrera, R.; Bastidas-Bastidas, P.d.J.; Valenzuela-Quintanar, A.I.; Pérez-Camarillo, J.P.; González-Mendoza, V.M.; Perea-Domínguez, X.P.; Márquez-Pacheco, H.; Amillano-Cisneros, J.M.; Badilla-Medina, C.N. Validation and application of liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry method for the analysis of glyphosate, aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), and glufosinate in soil. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyiem, W.; Hongsibson, S.; Chantara, S.; Kerdnoi, T.; Patarasiri, V.; Prapamonto, T.; Sapbamrer, R. Determination and assessment of glyphosate exposure among farmers from northern part of Thailand. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2017, 12, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Campenhout, L. Fermentation technology applied in the insect value chain: Making a win-win between microbes and insects. J. Insects Food Feed 2021, 7, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Kokko, C.; Ballard, C.; Dann, H.; Fustini, M.; Palmonari, A.; Formigoni, A.; Cotanch, K.; Grant, R. Influence of fiber degradability of corn silage in diets with lower and higher fiber content on lactational performance, nutrient digestibility, and ruminal characteristics in lactating Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 1728–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos, G.; Gonçalves, L.; Rodrigues, J.; Keller, K.; Coelho, M.; Michel, P.; Ottoni, D.; Jayme, D. Effect of re-ensiling on the quality of sorghum silage. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 6047–6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnomo, N.; Natsir, A.; Ako, A.; Ismartoyo, I. Comparative analysis of the biomass yield and nutrient content of corn varieties grown in rice fields during the dry season for ruminant feed. Open Vet. J. 2025, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, N.; Na, N.; Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, H.; Fang, Y.; Wang, T.; Xue, Y.; Zhong, J. Fermentation weight loss, fermentation quality, and bacterial community of ensiling of sweet sorghum with lactic acid bacteria at different silo densities. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1013913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Mertens, D.; Phillips, R. Effect of reduced ferulate-mediated lignin/arabinoxylan cross-linking in corn silage on feed intake, digestibility, and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5124–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Jung, C. Changes in nutritional composition from bee pollen to pollen patty used in bumblebee rearing. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2020, 23, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Olk, D.C.; Tewolde, H.; Zhang, H.; Shankle, M. Carbohydrate and amino acid profiles of cotton plant biomass products. Agriculture 2019, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanife, G. General principles of insect nutritional ecology. Trak. Univ. J. Sci. 2006, 7, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, H.M.; Nascimento, A.; Arruda, A.; Sarinho, A.; Lima, J.; Batista, L.; Dantas, M.F.; Andrade, R. Unlocking the potential of insect-based proteins: Sustainable solutions for global food security and nutrition. Foods 2024, 13, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley-Samuelson, D.W.; Jurenka, R.A.; Cripps, C.; Blomquist, G.J.; de Renobales, M. Fatty acids in insects: Composition, metabolism, and biological significance. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1988, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Sun, Q.; Tan, X.; You, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, M. Growth and fatty acid composition of black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) larvae are influenced by dietary fat sources and levels. Animals 2022, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolobe, S.D.; Manyelo, T.G.; Malematja, E.; Sebola, N.A.; Mabelebele, M. Fats and major fatty acids present in edible insects utilised as food and livestock feed. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, H.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, C.; Sun, L.; Wang, S. Impact of substrate digestibility on microbial community stability in methanogenic digestors: The mechanism and solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 352, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhang, K.; Liu, P.; Khan, A.; Xiong, J.; Tian, F.; Li, X. A critical review on the interaction of substrate nutrient balance and microbial community structure and function in anaerobic co-digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, J.; Muñoz-Dorado, J.; De la Rubia, T.; Martinez, J. Biodegradation and biological treatments of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin: An overview. Int. Microbiol. 2002, 5, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, D.J.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Van Elsas, J.D. Metataxonomic profiling and prediction of functional behaviour of wheat straw degrading microbial consortia. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satpathy, P.; Steinigeweg, S.; Cypionka, H.; Engelen, B. Different substrates and starter inocula govern microbial community structures in biogas reactors. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mondéjar, R.; Brabcová, V.; Štursová, M.; Davidová, A.; Jansa, J.; Cajthaml, T.; Baldrian, P. Decomposer food web in a deciduous forest shows high share of generalist microorganisms and importance of microbial biomass recycling. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1768–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Hong, J.; Jeong, S.; Chandran, K.; Park, K.Y. Interactions between substrate characteristics and microbial communities on biogas production yield and rate. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 303, 122934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, Y.; Chang, Z.; Yao, B.; Han, Z.; Wang, T.; Shang, N.; Wang, R. Innovative Lactic Acid Production Techniques Driving Advances in Silage Fermentation. Fermentation 2024, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.O.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, J. The performance of lactic acid bacteria in silage production: A review of modern biotechnology for silage improvement. Microbiological Research 2023, 266, 127212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma, O.B.; Rafatullah, M.; Tajarudin, H.A.; Ismail, N. Lignocellulolytic enzymes in biotechnological and industrial processes: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ni, K.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yang, F. Fermentation characteristics, chemical composition and microbial community of tropical forage silage under different temperatures. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 32, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisham, M.B.; Hashim, A.M.; Mohd Hanafi, N.; Abdul Rahman, N.; Abdul Mutalib, N.E.; Tan, C.K.; Nazli, M.H.; Mohd Yusoff, N.F. Bacterial communities associated with silage of different forage crops in Malaysian climate analysed using 16S amplicon metagenomics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.; Tashiro, Y.; Sakai, K. New application of Bacillus strains for optically pure L-lactic acid production: General overview and future prospects. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016, 80, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ke, W.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, G. Effects of Bacillus coagulans and Lactobacillus plantarum on the Fermentation Characteristics, Microbial Community, and Functional Shifts during Alfalfa Silage Fermentation. Animals 2023, 13, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Hindrichsen, I.; Klop, G.; Kinley, R.; Milora, N.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J. Effects of lactic acid bacteria silage inoculation on methane emission and productivity of Holstein Friesian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 7159–7174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, W.-I.; Chung, M.-S. Bacillus spores: A review of their properties and inactivation processing technologies. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 1447–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaracharanya, A.; Lorliam, W.; Tanasupawat, S.; Lee, K.C.; Lee, J.-S. Paenibacillus cellulositrophicus sp. nov., a cellulolytic bacterium from Thai soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2680–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Fu, W.; Bai, M.; Zhang, L.; Guo, B.; Qiao, Q.; Tao, R.; Kou, J. The degradation of residual pesticides and the quality of white clover silage are related to the types and initial concentrations of pesticides. J. Pestic. Sci. 2021, 46, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, D.; Li, F.; Bai, J.; Su, R. Current approaches on the roles of lactic acid bacteria in crop silage. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicini, J.L.; Reeves, W.R.; Swarthout, J.T.; Karberg, K.A. Glyphosate in livestock: Feed residues and animal health. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 4509–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Flake Soil Formulation | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient (%) | C | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |

| Sawdust | 46 | 34.5 | 23 | 11.5 | 0 | - |

| Corn stover | 0 | 11.5 | 23 | 34.5 | 46 | - |

| Cattle manure | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | - |

| Rice bran | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | - |

| Water | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | - |

| Proximate analysis (% DM) | ||||||

| Dry matter (DM) | 74.31 ± 0.34 | 74.25 ± 1.09 | 72.86 ± 0.17 | 73.04 ± 0.10 | 72.98 ± 0.65 | 0.285 |

| Ash | 16.22 ± 1.01 a | 15.38 ± 0.31 ab | 14.74 ± 0.50 ab | 11.81 ± 0.46 c | 12.48 ± 0.52 c | <0.001 |

| Crude fiber (CF) | 35.58 ± 0.84 a | 36.01 ± 1.53 a | 30.99 ± 1.19 b | 28.02 ± 0.58 b | 28.68 ± 0.87 b | <0.001 |

| Ether extract (EE) | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 0.86 ± 0.11 | 0.99 ± 0.18 | 0.99 ± 0.20 | 0.125 |

| Crude protein (CP) | 5.46 ± 0.27 b | 6.12 ± 0.28 ab | 6.95 ± 0.19 a | 7.53 ± 1.04 a | 7.49 ± 0.65 a | <0.001 |

| Nitrogen-free extract (NFE) | 24.17 ± 2.95 b | 27.89 ± 1.51 ab | 31.72 ± 0.87 a | 34.12 ± 1.41 a | 34.14 ± 2.87 a | <0.001 |

| Cellulose | 29.73 ± 2.25 b | 31.93 ± 0.14 ab | 32.61 ± 0.50 ab | 33.83 ± 0.70 a | 33.05 ± 0.22 ab | <0.001 |

| Hemicellulose | 6.76 ± 3.35 c | 11.13 ± 1.89 bc | 13.18 ± 1.36 abc | 15.61 ± 1.93 ab | 17.42 ± 1.87 a | <0.001 |

| Lignin | 25.07 ± 3.68 a | 22.14 ± 1.82 a | 13.60 ± 1.53 b | 6.67 ± 1.52 c | 7.30 ± 0.13 c | <0.001 |

| Gross Energy (GE) (kcal/100g) | 282.6 ± 11.53 | 303.5 ± 35.71 | 314.6 ± 22.91 | 300.2 ± 55.01 | 329.9 ± 36.04 | 0.469 |

| Amino Acid (mg/g Protein) | Treatments | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | ||

| Essential amino acid (EAAs) | ||||||

| His | 173 ± 1.5 e | 274 ± 1.7 d | 341 ± 0.5 c | 384 ± 1.7 b | 451 ± 1.1 a | <0.001 |

| Ile | 277 ± 7.57 d | 463 ± 15.94 c | 456 ± 3.4 c | 652 ± 4.6 b | 722 ± 6.3 a | <0.001 |

| Leu | 291 ± 4.0 e | 475 ± 36.2 d | 520 ± 5.1 c | 709 ± 8.0 b | 790 ± 1.1 a | <0.001 |

| Lys | 153 ± 0 e | 280 ± 2.6 d | 305 ± 1.1 c | 387 ± 5.5 b | 448 ± 3.6 a | <0.001 |

| Met | 23 ± 3.0 d | 31 ± 2.5 c | 56 ± 3.4 b | 55 ± 3.2 b | 64 ± 1.1 a | <0.001 |

| Phe | 104 ± 2.5 c | 202 ± 2.5 b | 195 ± 1.5 b | 243 ± 82.5 ab | 318 ± 2.8 a | <0.001 |

| Thr | 184 ± 30.0 c | 319 ± 5.0 b | 300 ± 0.5 b | 453 ± 8.6 a | 464 ± 0.0 a | <0.001 |

| Val | 347 ± 4.6 e | 600 ± 21.0 c | 560 ± 11.9 d | 810 ± 27.7b | 865 ± 8.6 a | <0.001 |

| Non-essential amino acid (NAAs) | ||||||

| Ala | 297 ± 2.3 d | 506 ± 9.2 c | 499 ± 1.5 c | 660 ± 3.7 b | 718 ± 0.5 a | <0.001 |

| Arg | 151 ± 20.7 c | 298 ± 37.8 b | 327 ± 1.5 b | 482 ± 3.0 a | 489 ± 1.1 a | <0.001 |

| Asp | 396 ± 7.0 e | 653 ± 9.7 c | 595 ± 1.1 d | 866 ± 9.2 b | 971 ± 2.8 a | <0.001 |

| Cys | ND | 13 ± 6.3 | 9 ± 0.5 | 14 ± 7.5 | 17 ± 9.8 | 0.563 |

| Gly | 271 ± 1.5 e | 451 ± 7.0 c | 437 ± 2.5 d | 615 ± 3.6 b | 666 ± 0.5 a | <0.001 |

| Glu | 513 ± 2.5 e | 883 ± 0.5 c | 863 ± 8.0 d | 1096 ± 17.0 b | 1260 ± 11.5 a | <0.001 |

| Pro | 234 ± 13.0 d | 396 ± 28.0 c | 411 ± 6.6 c | 530 ± 53.0 b | 639 ± 1.1 a | <0.001 |

| Ser | 160 ± 41.5 c | 298 ± 1.5 b | 286 ± 2.0 b | 419 ± 18.7 a | 438 ± 1.1 a | <0.001 |

| Tyr | ND | 34 ± 2.3 d | 91 ± 8.7 c | 117 ± 11.2 b | 165 ± 2.3 a | <0.001 |

| Fatty Acid (% of Total Fatty Acid) | Treatments | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | ||

| Saturated fatty acid (SFA) | ||||||

| Arachidic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Behenic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Butyric acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Capric acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Caproic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Caprylic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Heneicosanoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Heptadecanoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Lauric acid | 1.95 ± 0.63 | 1.98 ± 0.31 | 2.56 ± 0.31 | 2.13 ± 0.14 | 2.50 ± 0.16 | 0.183 |

| Lignoceric acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Myristic acid | 3.71 ± 0.37 | 4.44 ± 0.20 | 4.46 ± 0.62 | 3.70 ± 0.29 | 4.40 ± 0.33 | 0.066 |

| Palmitic acid | 56.83 ± 3.47 | 54.47 ± 2.79 | 48.98 ± 4.01 | 52.62 ± 7.23 | 53.95 ± 10.63 | 0.659 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Stearic acid | 20.22 ± 1.06 | 21.21 ± 2.37 | 20.70 ± 5.30 | 24.23 ± 3.01 | 18.81 ± 0.81 | 0.320 |

| Tricosanoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Tridecanoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Undecanoic acid (I.S) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) | ||||||

| cis-10-Heptadecenoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-10-Pentadecenoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis11-Eicosenic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Elaidic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Erucic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Linolelaidic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Myristoleic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Nervonic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Oleic acid | 34.87 ± 0.96 | 36.03 ± 2.96 | 34.38 ± 2.30 | 33.95 ± 2.99 | 34.55 ± 1.89 | 0.847 |

| Palmitoleic acid | 3.51 ± 0.35 | 5.05 ± 0.46 | 5.26 ± 1.10 | 3.45 ± 0.88 | 5.46 ± 0.91 | 0.054 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) | ||||||

| Arachidonic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-11,14,17-Eicosatrienoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-11,14-Eicosadienoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-13,16-Docosadienoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-4,7,10,13,16,19-Docosahexaenoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-5,8,11,14,17-Eicosapentaenoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| cis-8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Linoleic acid | 13.38 ± 0.63 | 13.59 ± 0.71 | 14.40 ± 1.68 | 15.42 ± 1.06 | 15.79 ± 0.40 | 0.054 |

| Linolenic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| r-Linolenic acid | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Danmek, K.; Pisithkul, T.; Jung, C.; Sun, S.; Jang, H.; Hongsibsong, S.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, M.C.; Praphawilai, P.; Burgett, M.; et al. Fermentation of Lignocellulosic Substrates Enhances the Safety and Nutritional Quality of Flake Soil for Rhinoceros Beetle Rearing. Polymers 2026, 18, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010095

Danmek K, Pisithkul T, Jung C, Sun S, Jang H, Hongsibsong S, Ghosh S, Wu MC, Praphawilai P, Burgett M, et al. Fermentation of Lignocellulosic Substrates Enhances the Safety and Nutritional Quality of Flake Soil for Rhinoceros Beetle Rearing. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010095

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanmek, Khanchai, Tippapha Pisithkul, Chuleui Jung, Sukjun Sun, Hyeonjeong Jang, Surat Hongsibsong, Sampat Ghosh, Ming Cheng Wu, Pichet Praphawilai, Michael Burgett, and et al. 2026. "Fermentation of Lignocellulosic Substrates Enhances the Safety and Nutritional Quality of Flake Soil for Rhinoceros Beetle Rearing" Polymers 18, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010095

APA StyleDanmek, K., Pisithkul, T., Jung, C., Sun, S., Jang, H., Hongsibsong, S., Ghosh, S., Wu, M. C., Praphawilai, P., Burgett, M., & Chuttong, B. (2026). Fermentation of Lignocellulosic Substrates Enhances the Safety and Nutritional Quality of Flake Soil for Rhinoceros Beetle Rearing. Polymers, 18(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010095