Physics-Informed Neural-Network-Based Generation of Composite Representative Volume Elements with Non-Uniform Distribution and High-Volume Fractions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. RVE Generating Methods

2.1. Initialization of Fiber Coordinates

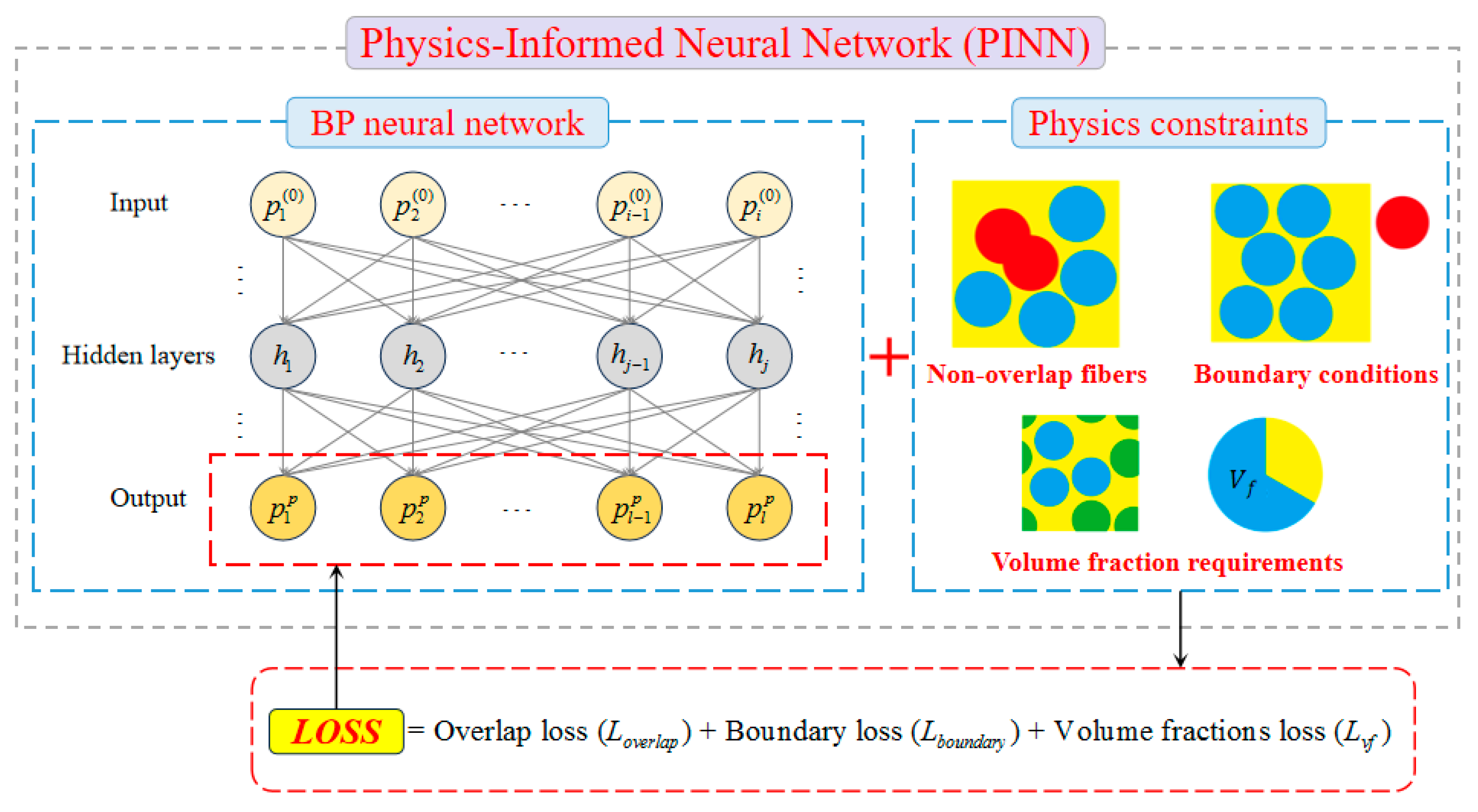

2.2. Definition of Loss Function

2.3. Backpropagation Neural Network and Optimization Process

3. Results and Discussion

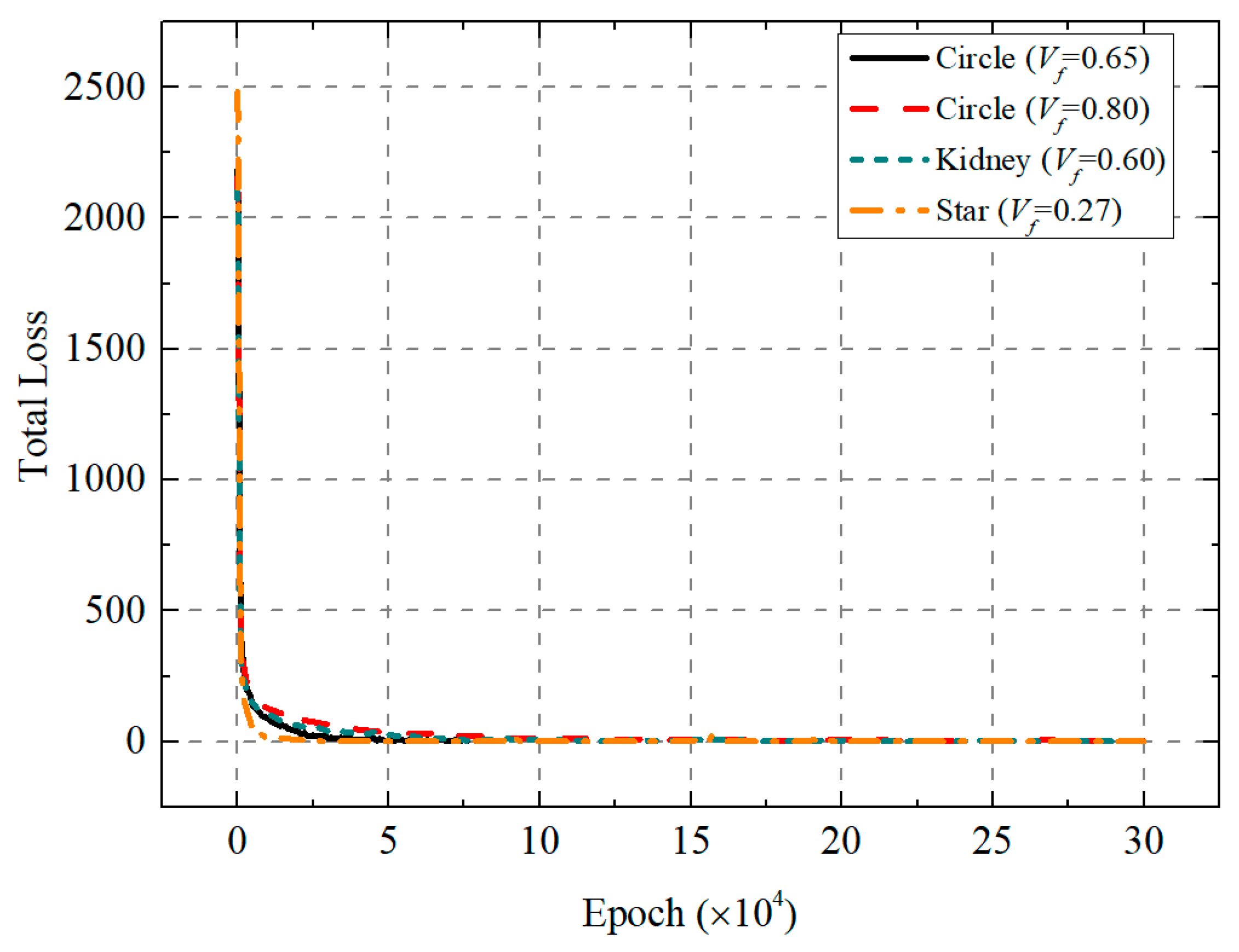

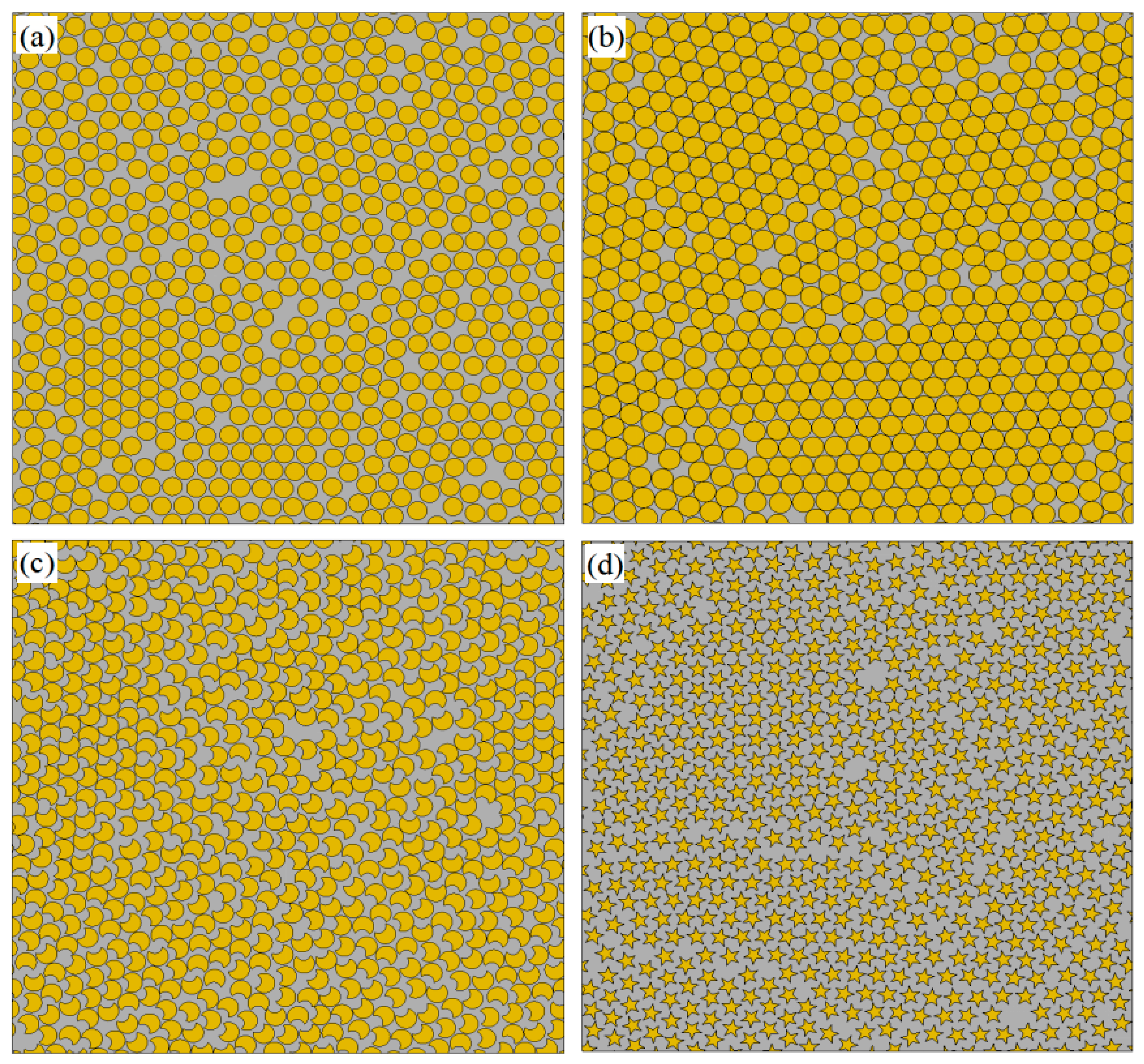

3.1. RVE Generation

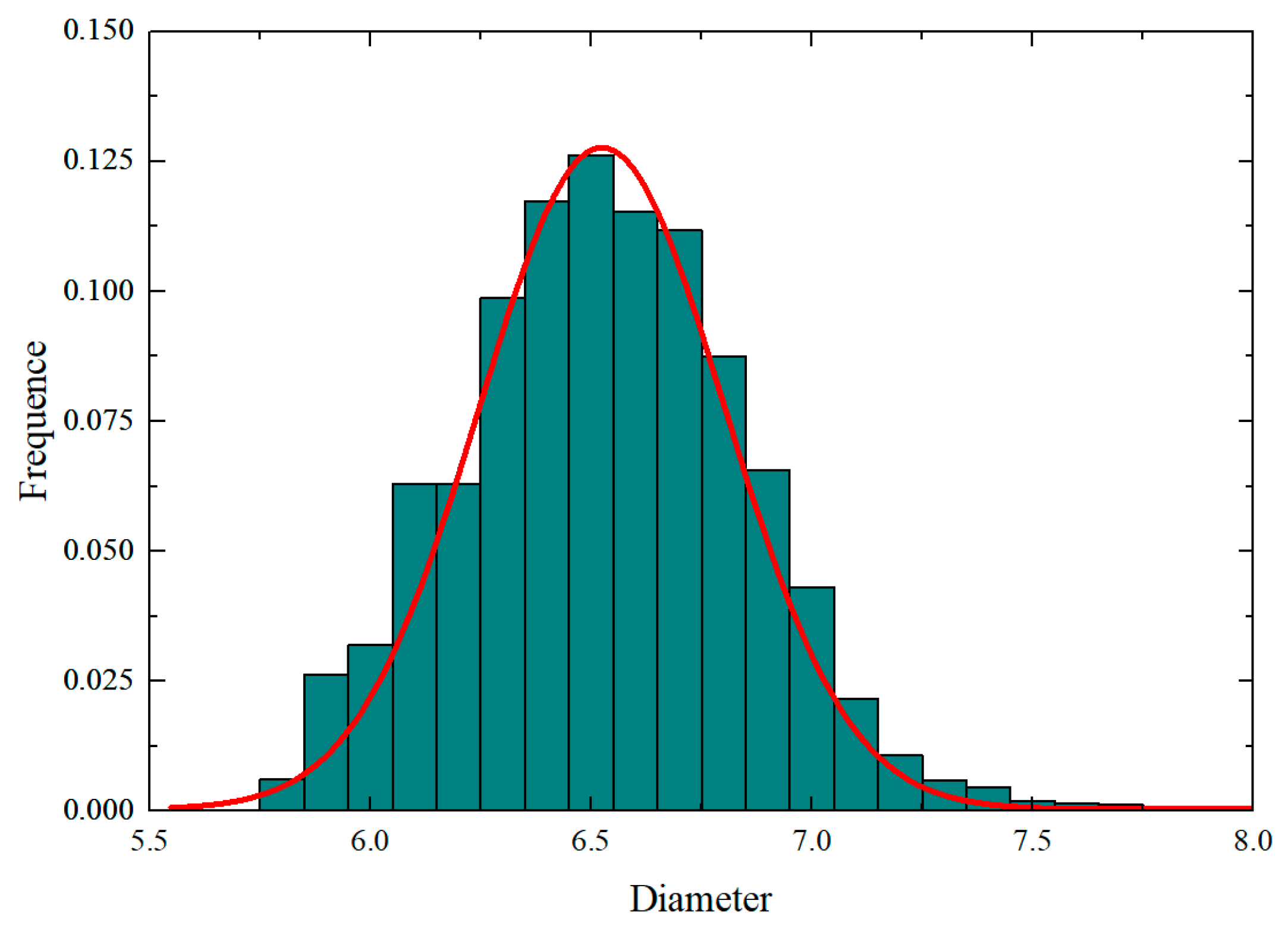

3.2. Statistical Characterization Analysis

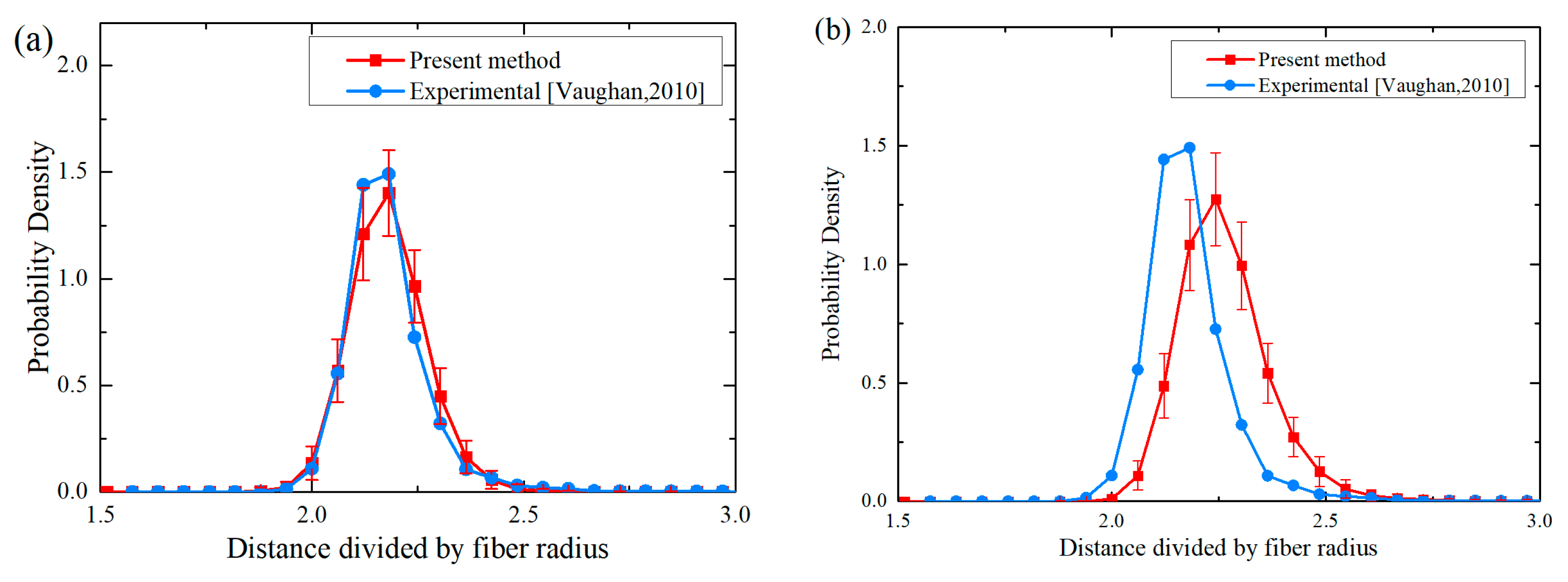

3.2.1. Nearest Neighbor Distances

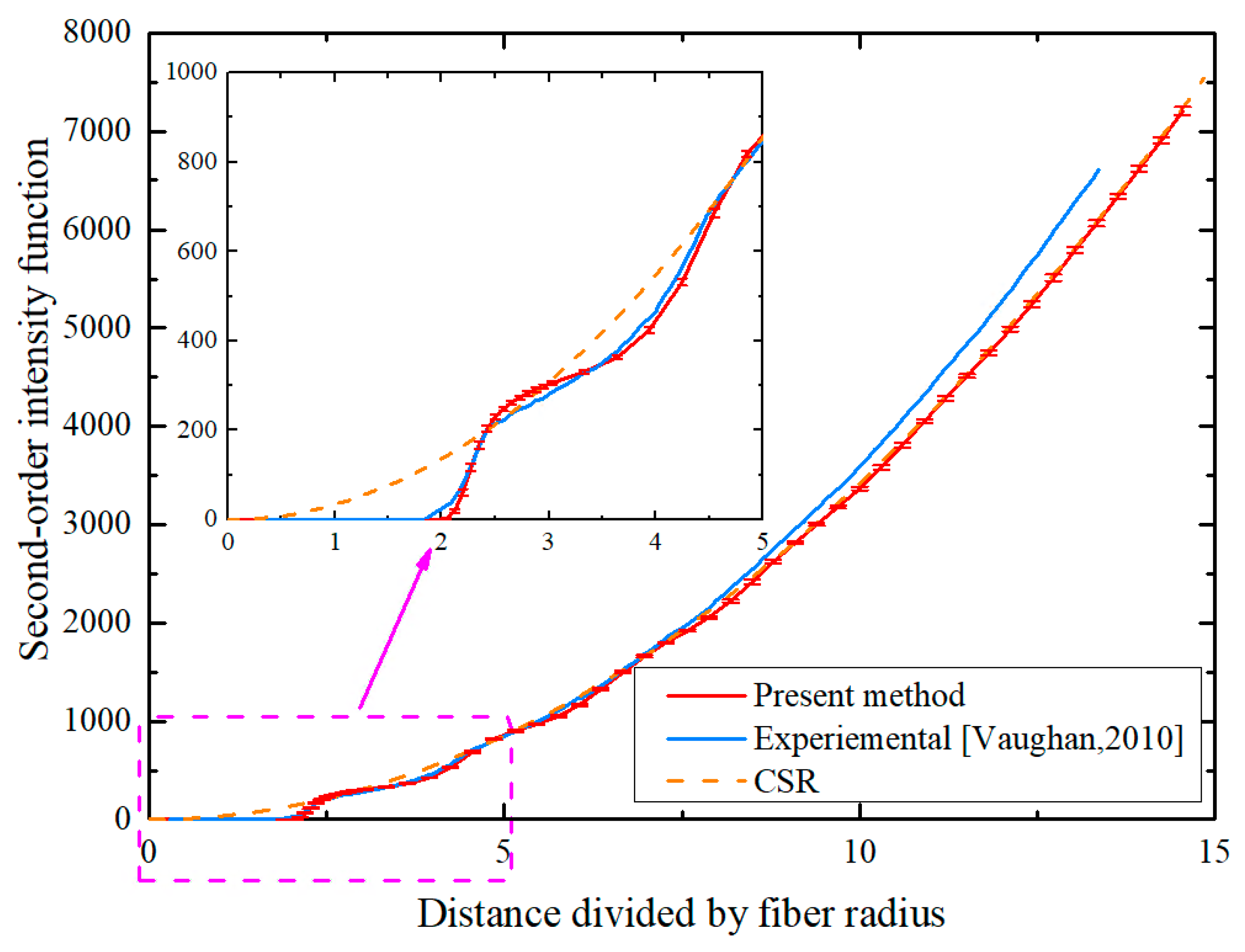

3.2.2. Second-Order Intensity Function

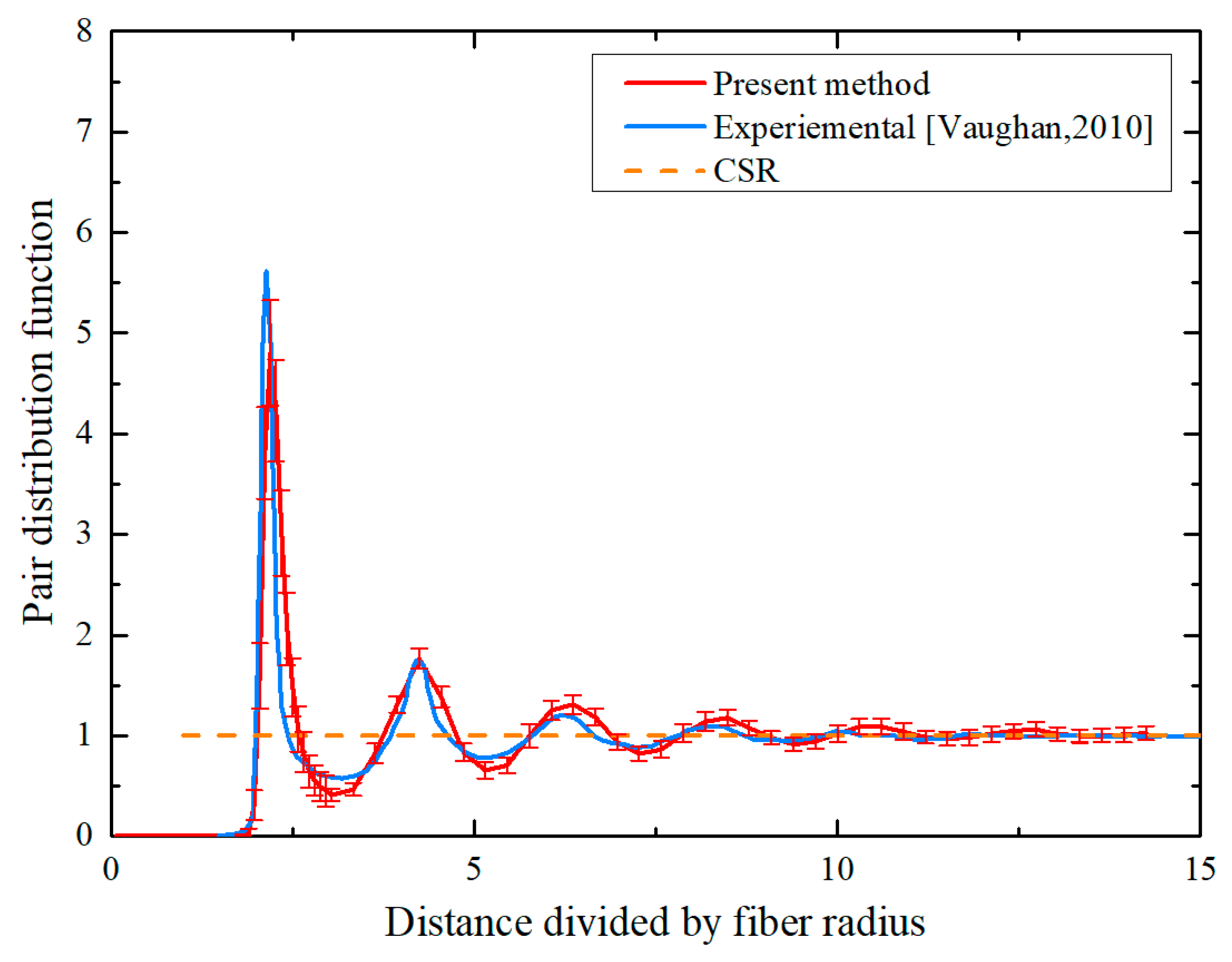

3.2.3. Pair Distribution Function

3.3. Mechanical Performance Prediction

3.3.1. Effective Elastic Property Prediction

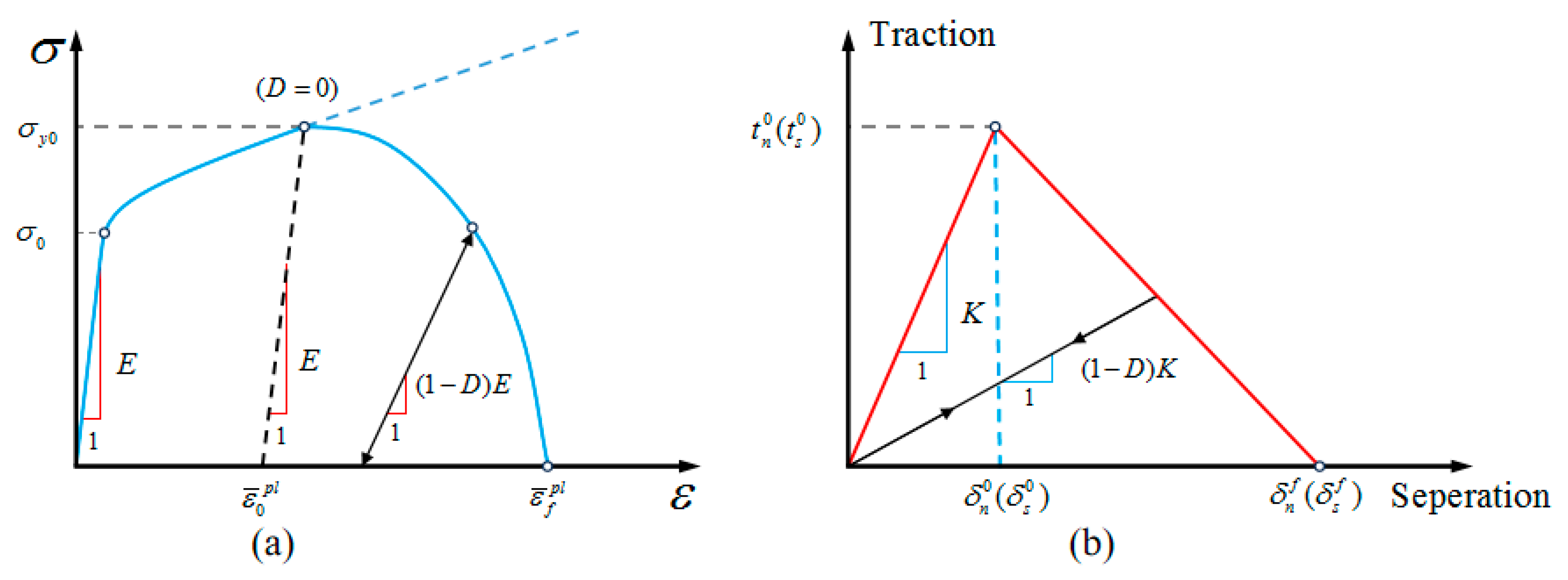

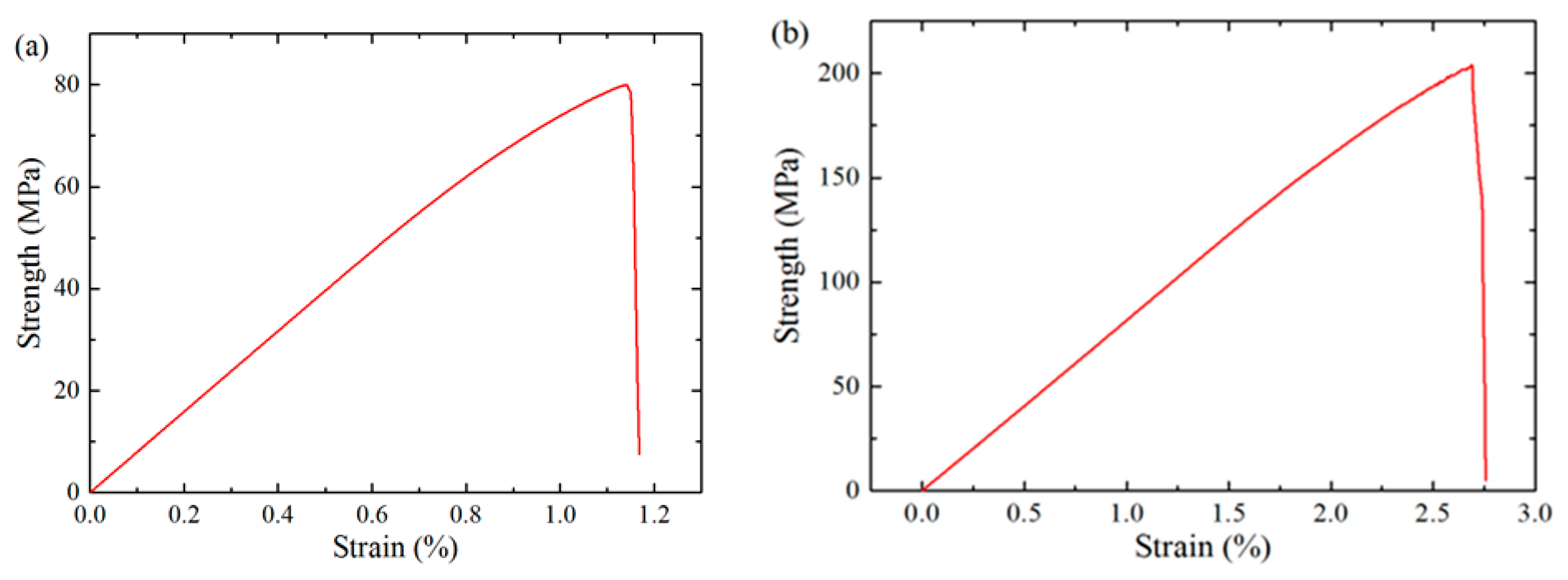

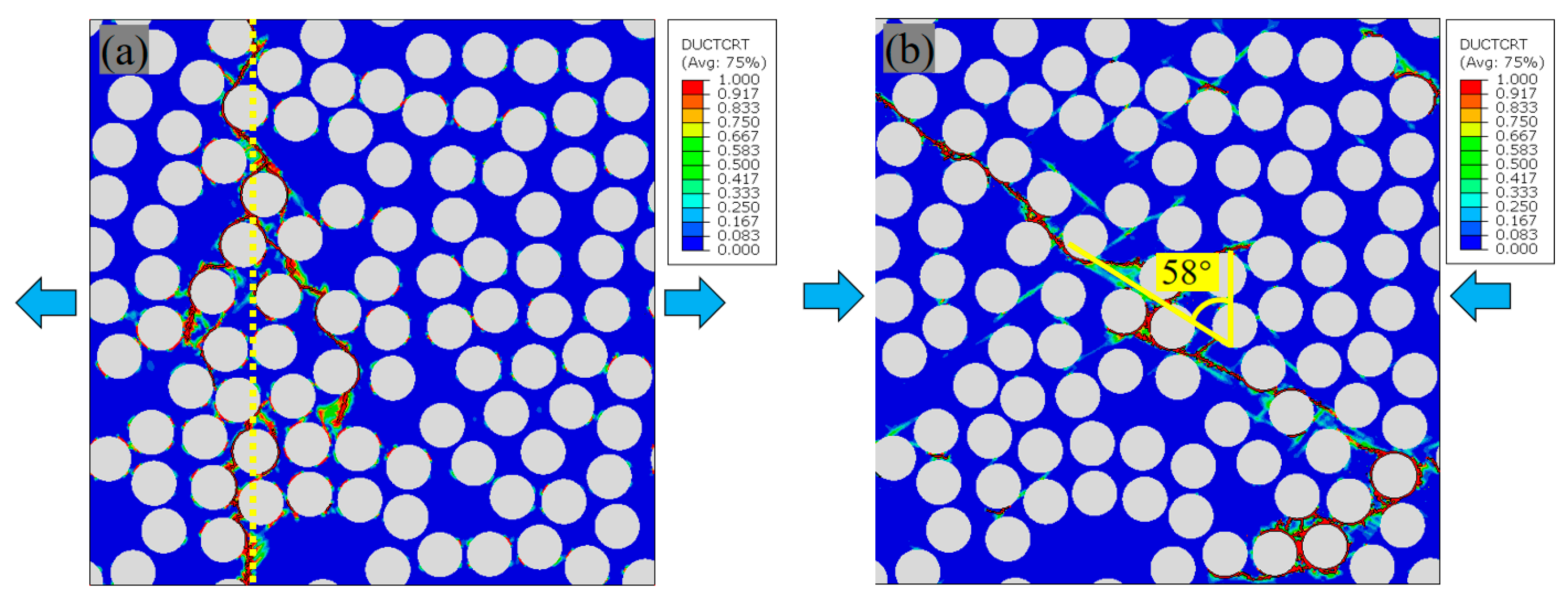

3.3.2. Strength and Damage Behavior Analysis

4. Conclusions

- The PINN-based method proposed in this work eliminates the reliance on massive training sets required by conventional neural networks and overcomes the jamming limit in traditional generation techniques like RSA, raising the maximum achievable volume fraction to 0.8 while simultaneously enabling controllable spatial gaps in fiber arrangements.

- Statistical examinations involve nearest neighbor distances, the second-order intensity function, and the pair distribution function conducted on the generated RVEs. These examinations reveal that the PINN-based methodology can accurately reconstruct fiber spatial distributions observed in actual composite materials, particularly at the crucial short-range level where fiber interactions are most significant.

- Finite element simulations were conducted on RVEs generated by the proposed method to predict their elastic properties and damage behaviors. The results show that the predictions are consistent with experimental data, validating the effectiveness of the PINN-based method in generating RVEs for micromechanical studies in composite materials.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vijayan, D.S.; Sivasuriyan, A.; Devarajan, P.; Stefańska, A.; Wodzyński, Ł.; Koda, E. Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Composites in Civil Engineering Application. Buildings 2023, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Llorca, J. Mechanical behavior of unidirectional fiber-reinforced polymer-sunder transverse compression: Microscopic mechanisms and modeling. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 2795–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Monastyreckis, G.; Zeleniakiene, D. Numerical Study on Elastic Properties of Natural Fibres in Multi-Hybrid Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Luan, X.; Meng, B.; Liu, J.; Lu, Y. Effects of Void Characteristics on the Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polyetheretherketone Composites: Micromechanical Modeling and Analysis. Polymers 2025, 17, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayoor, H.; Hoa, V.; Marsden, C. A micromechanical study of stress concentrations in composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 132, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Yin, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, R.; He, X. A versatile and highly efficient algorithm to generate representative microstructures for heterogeneous materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 241, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostoja-Starzewski, M.; Kale, S.; Karimi, P.; Malyarenko, A.; Raghavan, B.; Ranganathan, S.; Zhang, J. Scaling to RVE in random media. Compos. Struct. 2016, 49, 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hojo, M.; Mizuno, M.; Hobbiebrunken, T.; Adachi, T.; Tanaka, M.; Ha, S.K. Effect of fiber array irregularities on micro-scopic interfacial normal stress states of transversely loaded UD-CFRP from viewpoint of failure initiation. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1726–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Gokhale, A. Application of image analysis for characterization of spatial arrangements of features in microstructure. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1995, 26, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, Z.; Sun, X.; Tang, Z. A virtual experimental approach to estimate composite mechanical properties: Modeling with an explicit finite element method. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2010, 49, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, J. Random Sequential Adsorption. J. Theor. Biol. 1980, 87, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tewari, A.; Gokhale, A.M. Modeling of non-uniform spatial arrangement of fibers in a ceramic matrix composite. Acta Mater. 1997, 45, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buryachenko, V.; Pagano, N.; Kim, R.; Spowart, J. Quantitative description and numerical simulation of random microstructures of composites and their effective elastic moduli. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2003, 40, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Random sequential adsorption, series expansion and Monte Carlo simulation. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 1998, 254, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melro, A.; Camanho, P.; Pinho, S. Generation of random distribution of fibres in long-fibre reinforced composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yan, Y.; Ran, Z.; Liu, Y. A new method for generating random fibre distributions for fibre reinforced composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 76, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Mao, L.; Xin, Z.; Ding, L. Experimental characterization and micro-modeling of transverse tension behavior for unidirectional glass fibre-reinforced composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 222, 109359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, T.; McCarthy, C. A combined experimental-numerical approach for generating statistically equivalent fibre distributions for high strength laminated composite materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, X.; Zhao, M. Micromechanical modeling of fiber-reinforced composites with statistically equivalent random fiber distribution. Materials 2016, 9, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusev, A.; Hine, P.; Ward, I. Fiber packing and elastic properties of a transversely random unidirectional glass/epoxy composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsto, A.; Li, S. Micromechanical FE analysis of UD fibre-reinforced composites with fibres distributed at random over the transverse cross-section. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2005, 36, 1246–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalanotti, G. On the generation of RVE-based models of composites reinforced with long fibres or spherical particles. Compos. Struct. 2016, 138, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Y.; Yang, D.; Ye, J. Discrete element method for generating random fibre distributions in micromechanical models of fibre reinforced composite laminates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 90, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisram, M.; Ahmed, J.; Hood, A.; Cao, J. A novel method for creation of complex microstructure cells through artificial molecular dynamics simulations. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 232, 109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, A.; Li, G.; Willett, T.L.; Montesano, J. Three-dimensional microscopic assessment of randomly distributed representative volume elements for high fiber volume fraction unidirectional composites. Compos. Struct. 2018, 192, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sharifpour, F.; Bahmani, A.; Montesano, J. A new approach to rapidly generate random periodic representative volume elements for microstructural assessment of high volume fraction composites. Mater. Des. 2018, 150, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herráez, M.; Segurado, J.; González, C.; Lopes, C. A microstructures generation tool for virtual ply property screening of hybrid composites with high volume fractions of non-circular fibers—VIPER. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 129, 105691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, M.; Tagarielli, V.; Patsias, S.; Baiz-Villafranca, P. A new algorithm to generate representative volume elements of composites with cylindrical or spherical fillers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakka, R.; Harursampath, D.; Pathan, M.; Ponnusami, S.A. A computationally efficient approach for generating RVEs of various inclusion/fibre shapes. Compos. Struct. 2022, 291, 115560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Xu, L.; Qi, L.; Chao, X. Minimum potential method appropriate to generate 2D RVEs of composites with high fiber volume fraction. Compos. Struct. 2023, 318, 117070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Wang, B.; Yin, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, R.; He, X. A new algorithm to generate non-uniformly dispersed representative volume elements of composite materials with high volume fractions. Mater. Des. 2022, 219, 110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, Z.; Cai, C.; He, X. A novel algorithm to generate representative volume elements with cylindrical fibers and sphere particles. J. Compos. Mater. 2024, 58, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Ke, Y. Greedy-based approach for generating anisotropic random fiber distributions of unidirectional composites and transverse mechanical properties prediction. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 218, 111966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, A.; Marshall, D.; Legault, Z.; Makovetsky, R.; Provencher, B.; Piché, N.; Marsh, M. Automated segmentation of computed tomography images of fiber-reinforced composites by deep learning. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 16273–16289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Ke, Y. Machine learning and materials informatics approaches for predicting transverse mechanical properties of unidirectional CFRP composites with microvoids. Mater. Des. 2022, 224, 111340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q. Mechanical Field Guiding Structure Design Strategy for Meta-Fiber Reinforced Hydrogel Composites by Deep Learning. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2310141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, N.; Rodet, T.; Lesselier, D. Identification and characterization of damaged fiber-reinforced laminates in a Bayesian framework. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2024, 74, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Marco, A.; Mahoor, M.; Christian, B.; Yentl, S. Synthesising realistic 2D microstructures of unidirectional fibre-reinforced composites with a generative adversarial network. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 250, 110539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linghu, J.; Gao, W.; Dong, H.; Nie, Y. Higher-order multi-scale physics-informed neural network (HOMS-PINN) method and its convergence analysis for solving elastic problems of authentic composite materials. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 456, 116223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Cheng, H.; Wang, C.; He, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Liang, B. A micromechanical solving method integrating the physics-informed neural network with the self-consistent cluster analysis method for composites laminate. Compos. Struct. 2025, 368, 119264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley, D. Modelling Spatial Patterns. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1977, 39, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. Elastic properties of reinforced solids: Some theoretical principles. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1963, 11, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostoja-Starzewski, M. Material spatial randomness: From statistical to representative volume element. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2006, 21, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soden, P.; Hinton, M.; Kaddour, A. Lamina properties, lay-up configurations and loading conditions for a range of fibre-reinforced composite laminates. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1998, 58, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Qi, L.; Chao, X.; Xue, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, H. The effects of interphase parameters on transverse elastic properties of Carbon-Carbon composites based on FE model. Compos. Struct. 2021, 268, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, M.; Vaughan, T.; McCarthy, C. Fibrous composite matrix characterisation using nanoindentation: The effect of fibre constraint and the evolution from bulk to in-situ matrix properties. Compos. Part A 2015, 68, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; McCarthy, M.; McCarthy, C. Comparison of open hole tension characteristics of high strength glass and carbon fibre-reinforced composite materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, D. Yielding of steel sheets containing slits. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1960, 8, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HKS Inc. ABAQUS Theory Manual; HKS Inc.: Dallas, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stachurski, H. Yield strength and anelastic limit of amorphous ductile polymers. J. Mater. Sci. 1986, 21, 3237–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ran, Z. Microscopic failure mechanisms of fiber-reinforced polymer composites under transverse tension and compression. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2012, 72, 1818–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, R. Effects of triangle-shape fiber on the transverse mechanical properties of unidirectional carbon fiber reinforced plastics. Compos. Struct. 2016, 152, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Algorithm Complexity | Achievable Maximum Volume Fraction | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scanning–reconstruction method | Easy to implement, requires substantial resources | Depends on the actual microstructures | Low |

| RSA algorithms | Easy to implement | <0.54 | Depends on volume fraction |

| Modified RSA algorithms | Depends on the algorithm | Depends on the algorithm | Depends on the algorithm |

| Initial periodic vibration models | Complex | Depends on the algorithm, cannot eliminate the initial pattern in high volume fraction | Depends on the algorithm |

| MD-based method | Complex | >0.8 | High |

| Displacement-based optimization method | Depends on the algorithm | >0.8 | Depends on optimization method |

| Biomimetic-based optimization method | Complex | Depends on the algorithm | Depends on optimization method |

| General machine learning method | Fair, requires substantial extensive training data | >0.8 | Low, training data preparation requires time |

| PINN-based method (presented work) | Easy to implement, no training samples required | >0.8 | High |

| (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 13.935 | 0.389 | 13.924 | 0.392 | 4.657 |

| Melro et al. [15] | 13.376 | 0.370 | 13.387 | 0.371 | 4.851 |

| Yang et al. [16] | 13.047 | 0.405 | 13.068 | 0.405 | 4.673 |

| Experiment [46] | 16.2 | 0.4 | 16.2 | 0.4 | 5.786 |

| Error (%) | 13.98 | 2.75 | 14.05 | 2.00 | 19.51 |

| Average | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.08 |

| Fiber (HTA) | |||||||

| 238 GPa | 28 GPa | 24 GPa | 7.2 GPa | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.02 | |

| Matrix (6376) | |||||||

| Elastic Properties | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental [49] | 139 | 10 | 10 | 5.2 | 0.32 |

| Average values | 142.32 | 10.32 | 10.24 | 4.96 | 0.29 |

| Errors (%) | 2.39 | 3.20 | 2.40 | 4.62 | 9.38 |

| Fiber | (GPa) | ||||

| 23.34 | 0.25 | ||||

| Matrix | (GPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | d (MPa) | |

| 3.45 | 0.35 | 85.7 | 232.5 | 104.8 | |

| β | k | (J/m2) | |||

| 37.7° | 0.8 | 0.025 | 0.25 | 5 | |

| Interphase | (GPa/m) | (MPa) | (J/m2) | ||

| 85.7 | 100 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, T.; Cai, C.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.; Liu, W. Physics-Informed Neural-Network-Based Generation of Composite Representative Volume Elements with Non-Uniform Distribution and High-Volume Fractions. Polymers 2026, 18, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010097

Zheng T, Cai C, Yang F, Wang R, Liu W. Physics-Informed Neural-Network-Based Generation of Composite Representative Volume Elements with Non-Uniform Distribution and High-Volume Fractions. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Tianlu, Chaocan Cai, Fan Yang, Rongguo Wang, and Wenbo Liu. 2026. "Physics-Informed Neural-Network-Based Generation of Composite Representative Volume Elements with Non-Uniform Distribution and High-Volume Fractions" Polymers 18, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010097

APA StyleZheng, T., Cai, C., Yang, F., Wang, R., & Liu, W. (2026). Physics-Informed Neural-Network-Based Generation of Composite Representative Volume Elements with Non-Uniform Distribution and High-Volume Fractions. Polymers, 18(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010097