Enhanced Energy Absorption and Flexural Performance of 3D Printed Sandwich Panels Using Slicer-Generated Interlocking Interfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

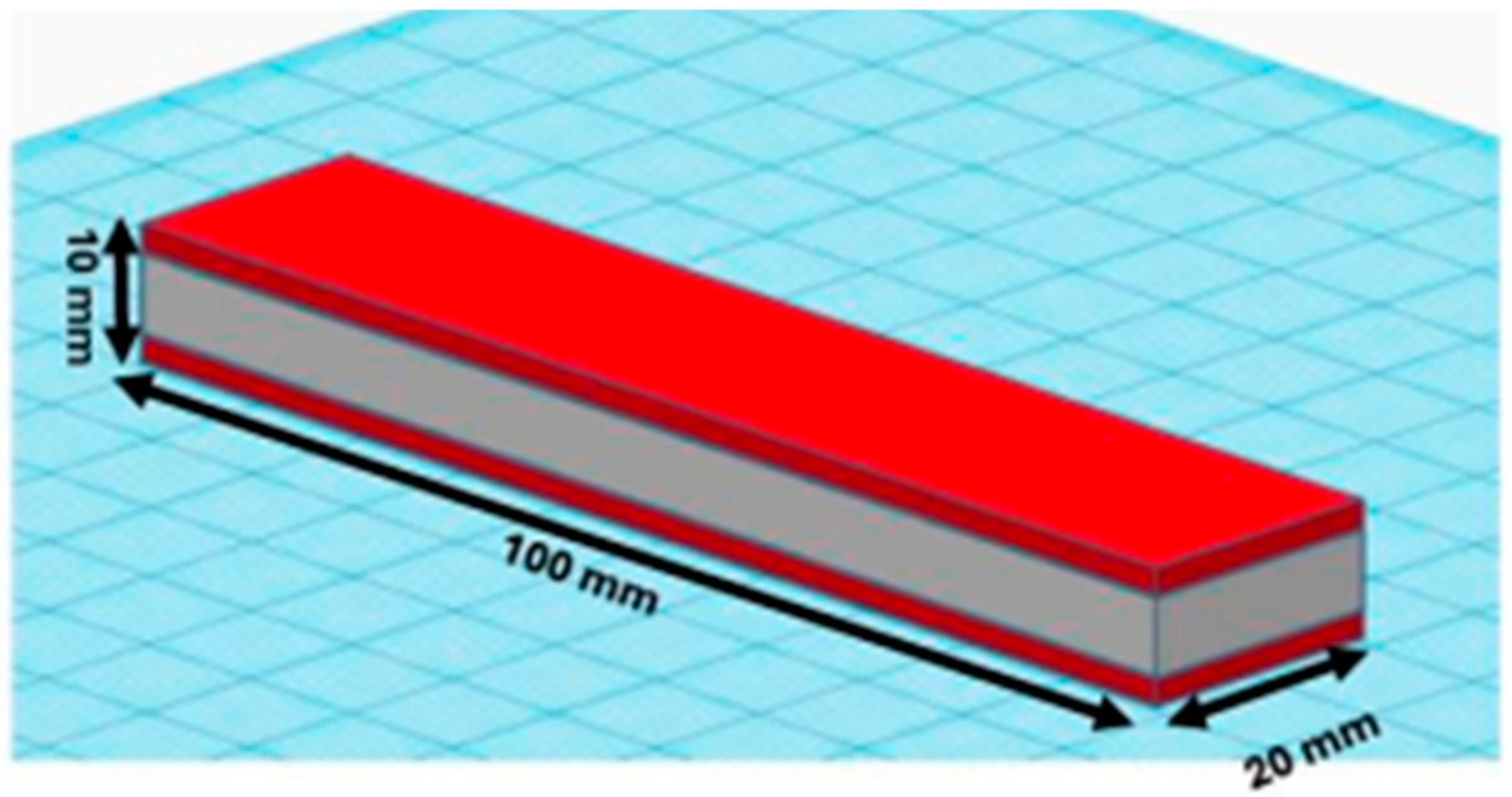

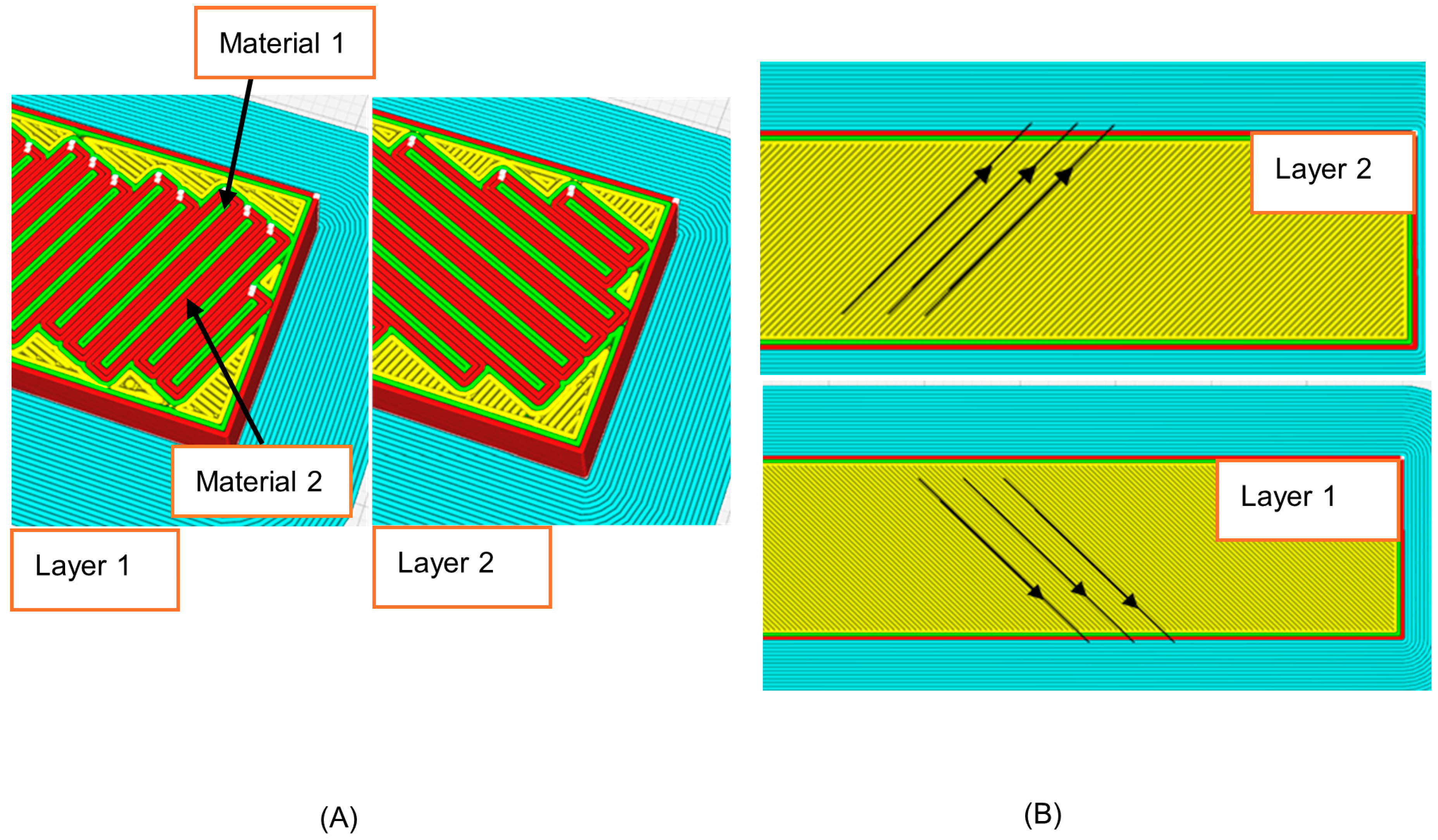

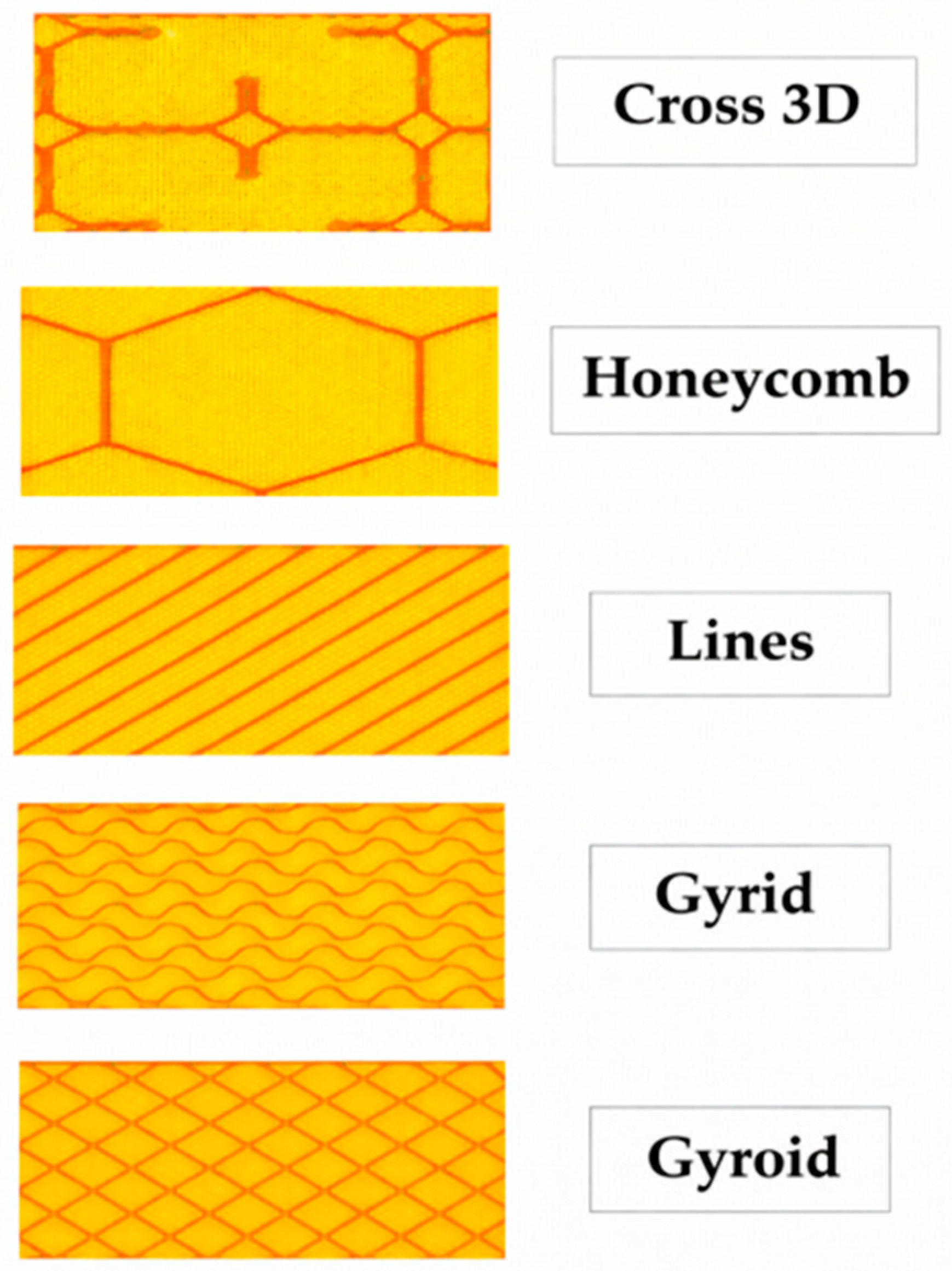

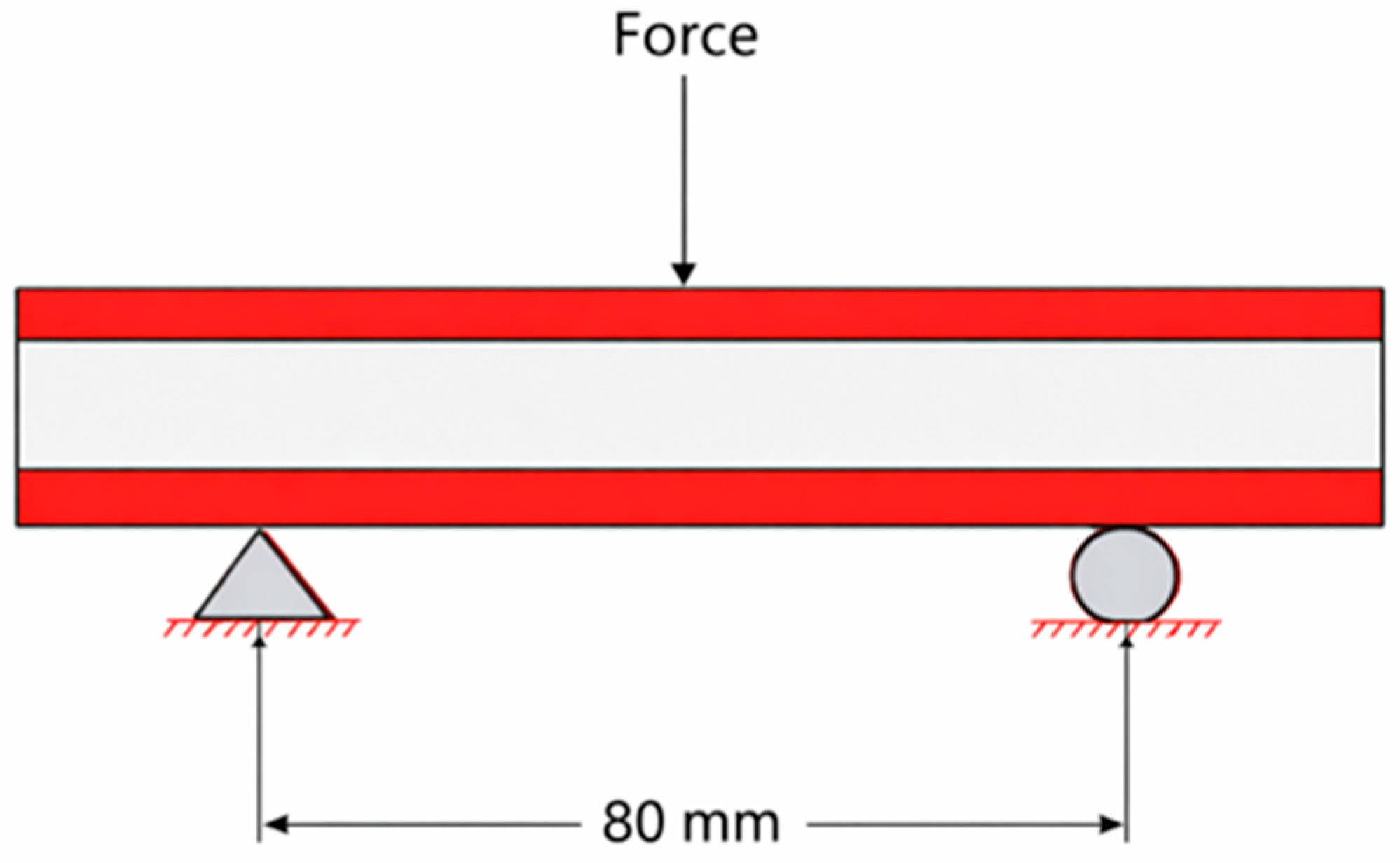

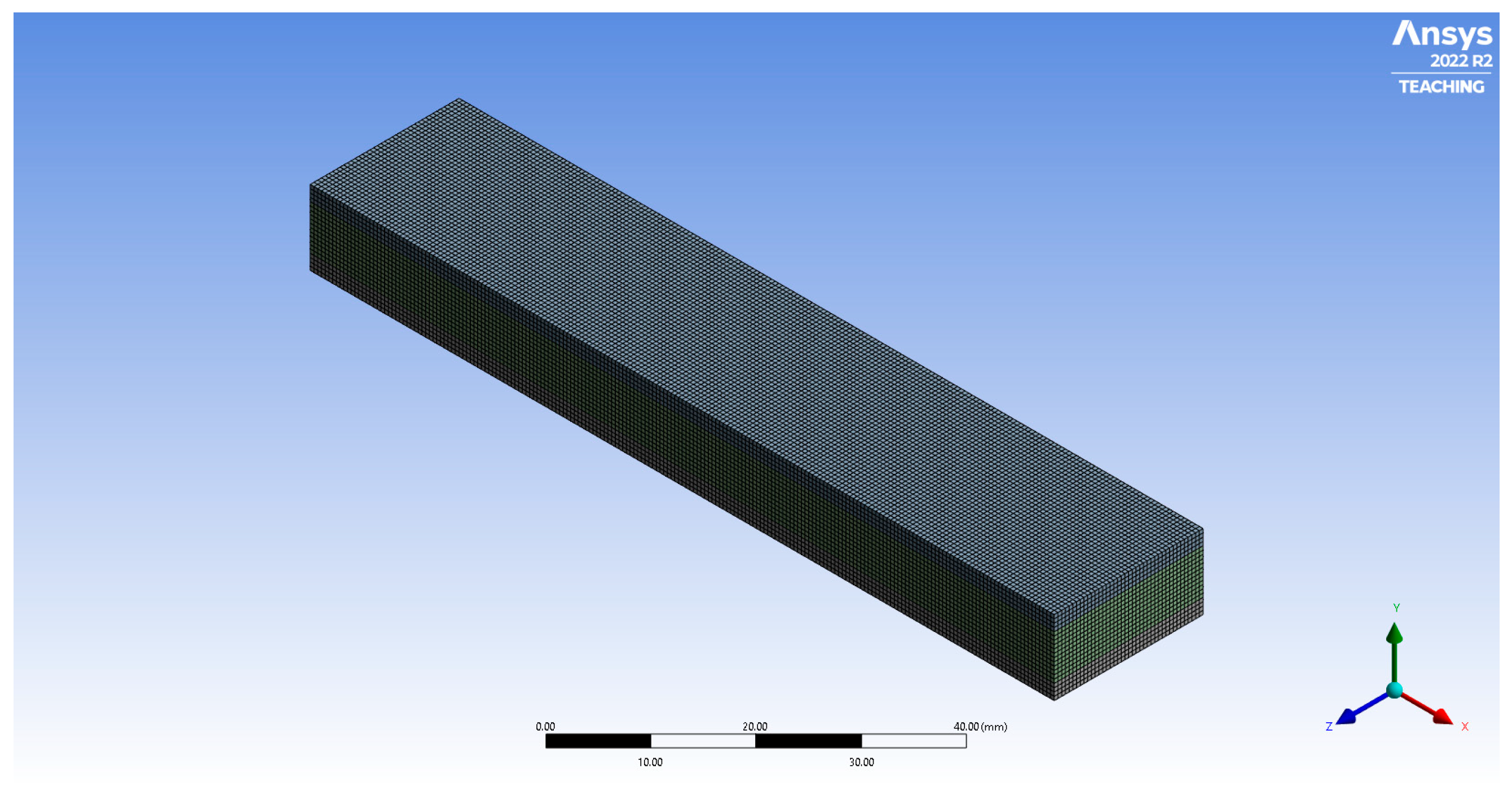

2. Methodology

3. Finite Element

4. Theoretical Analysis

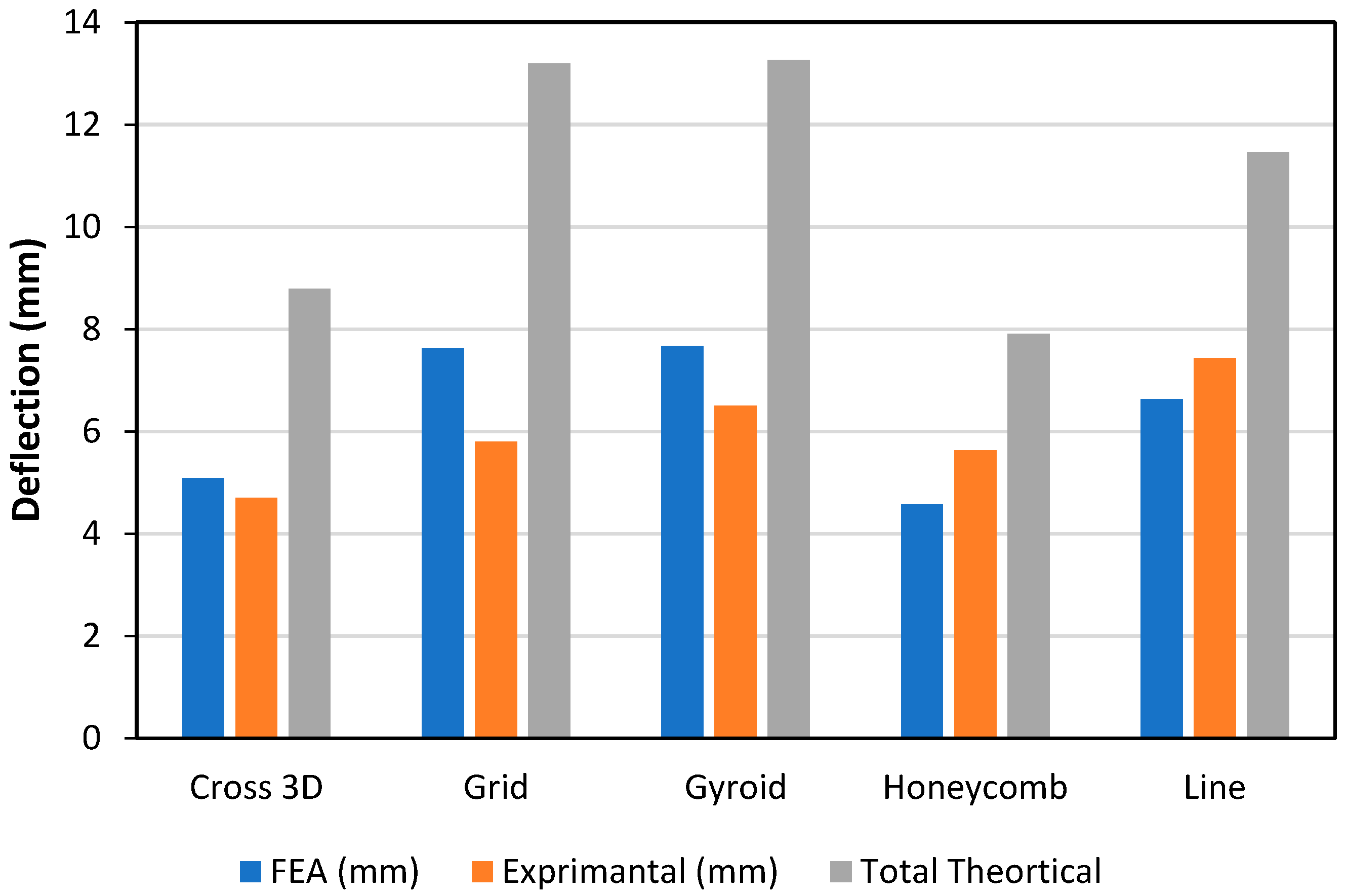

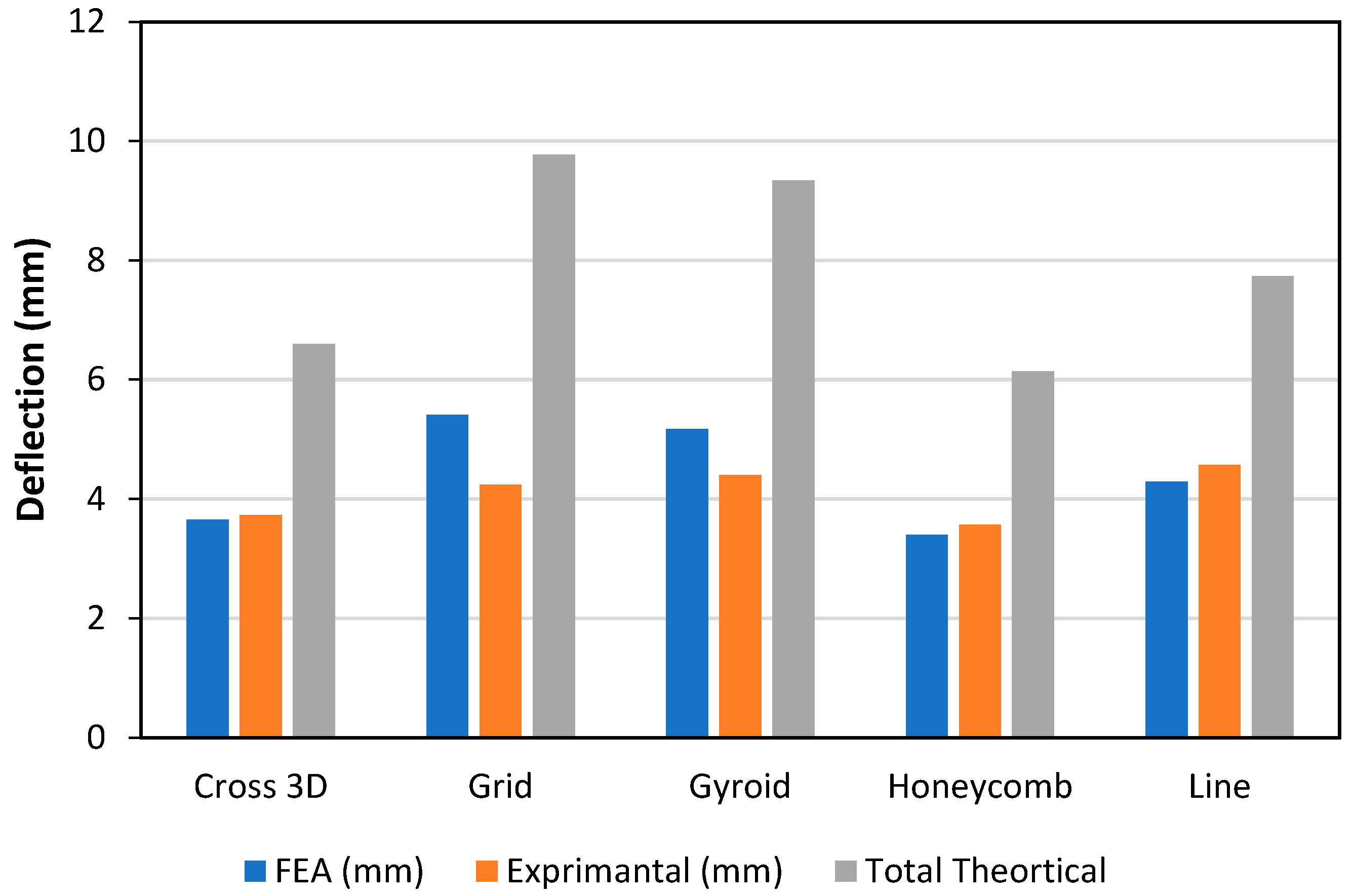

5. Results & Discussion

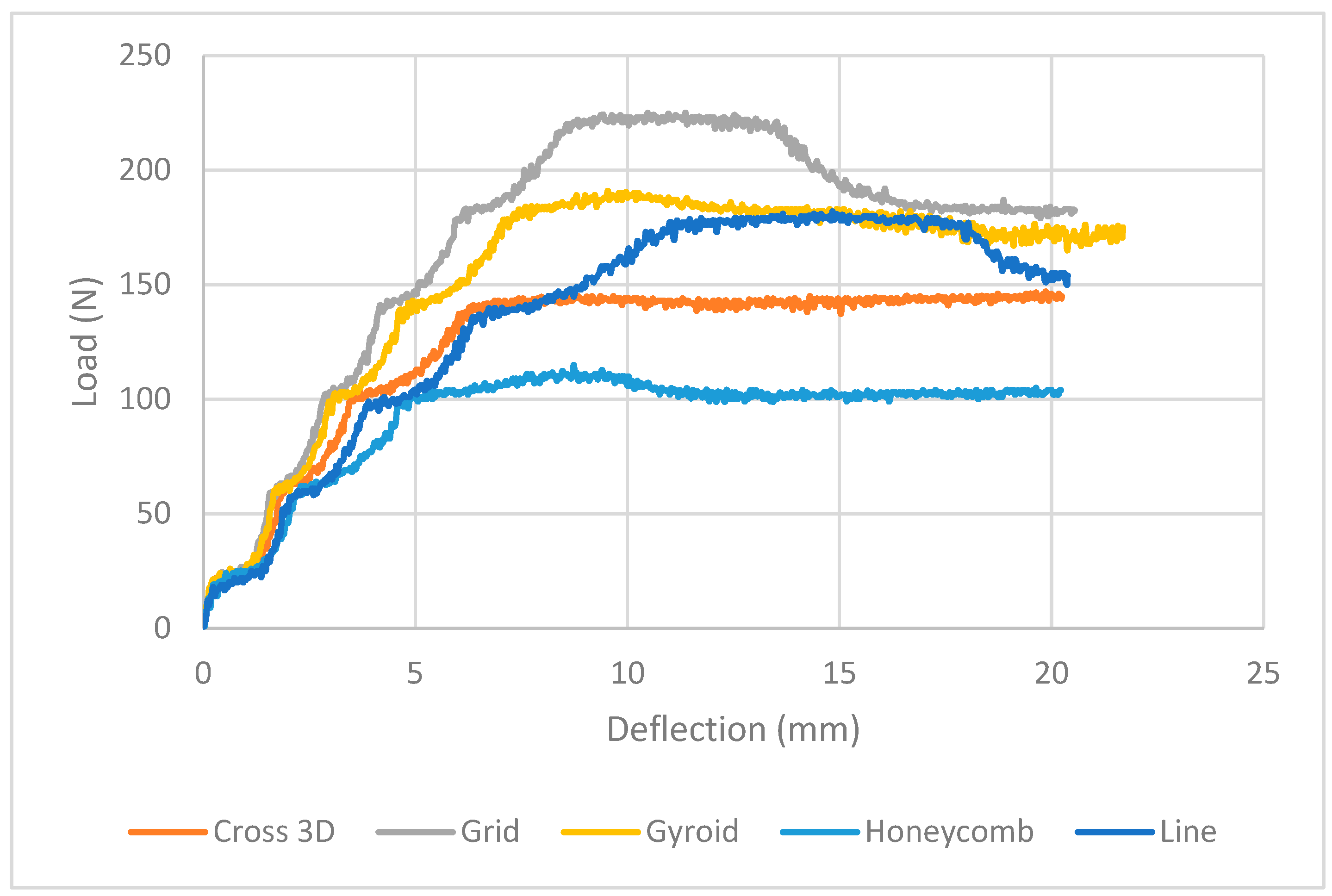

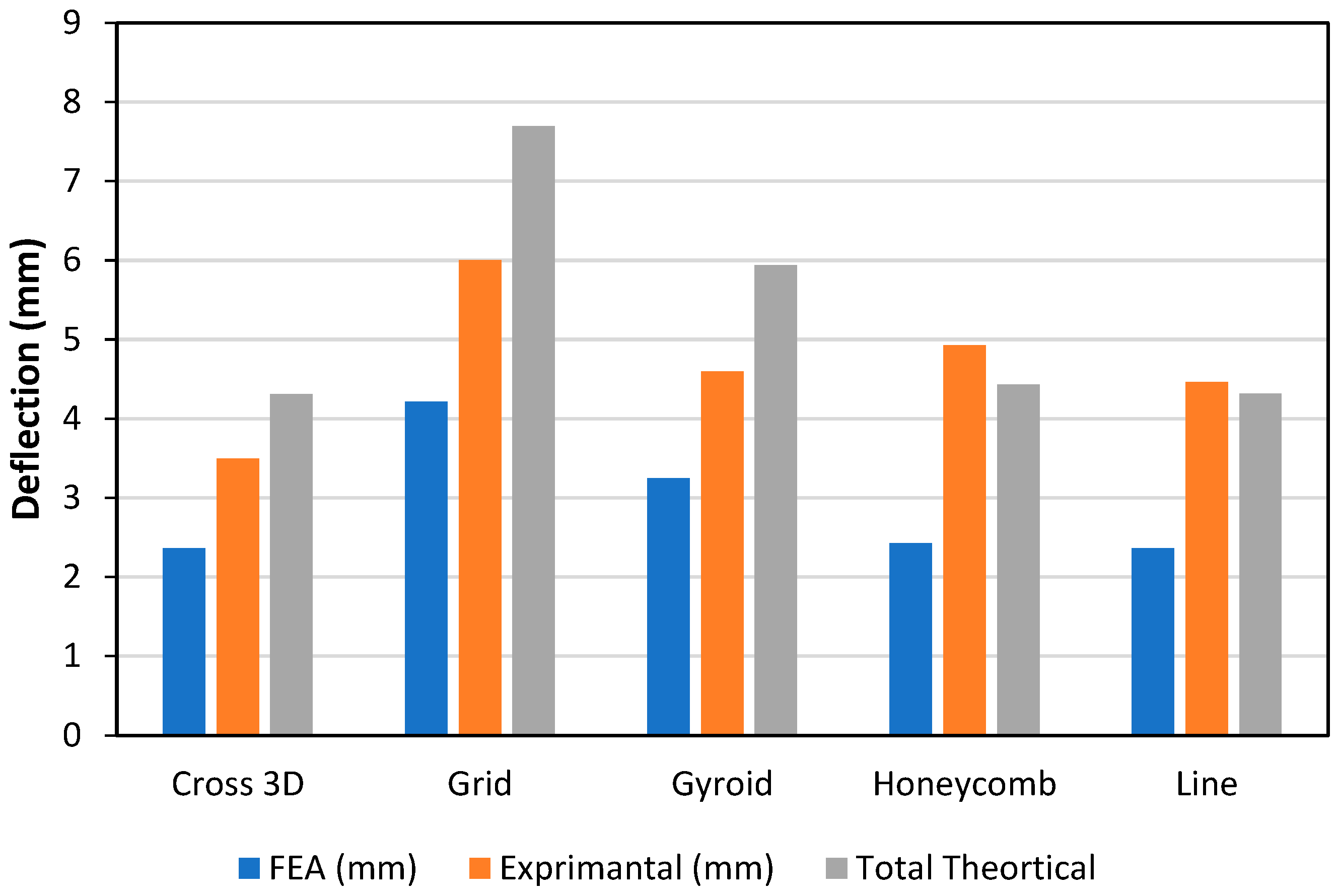

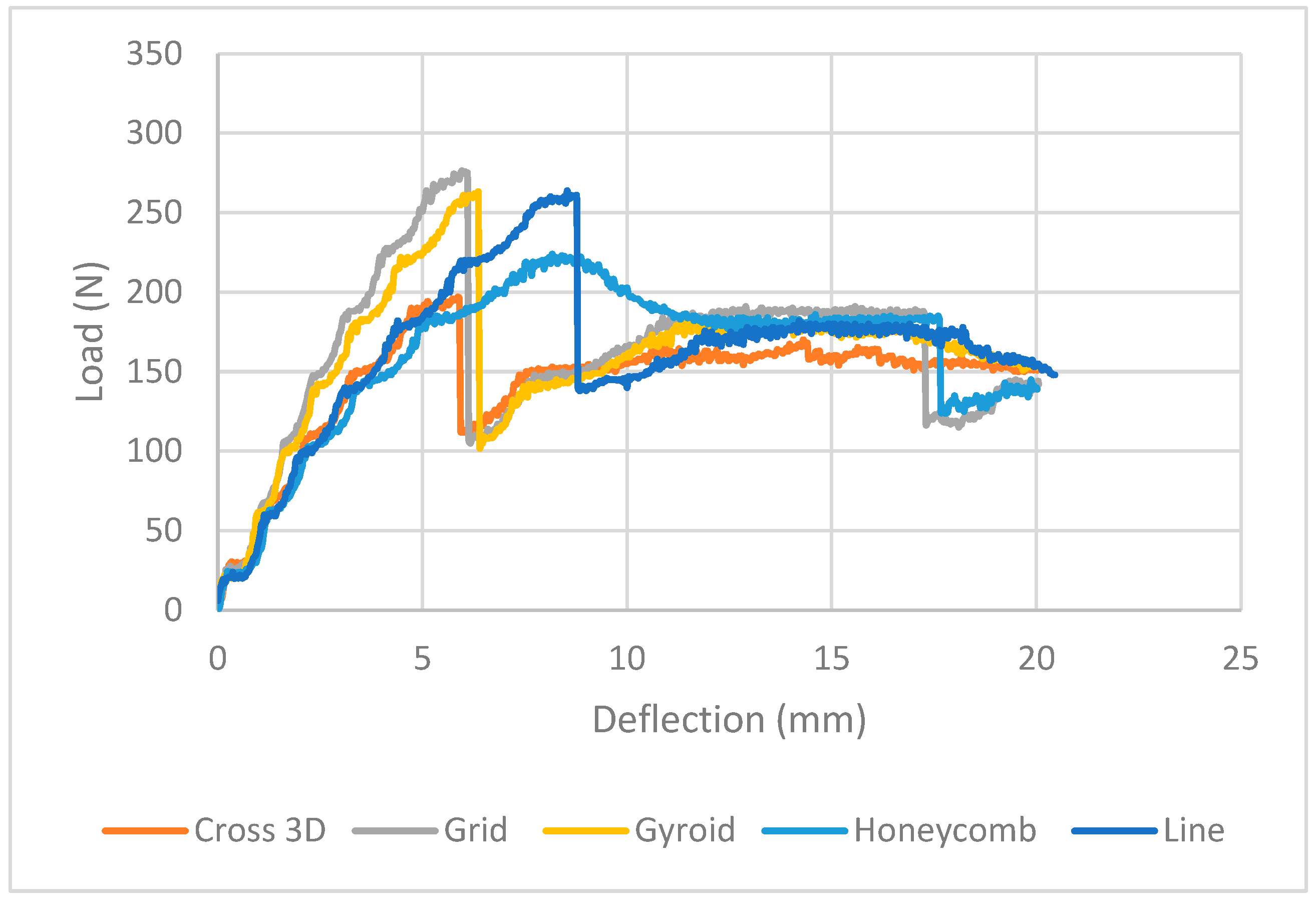

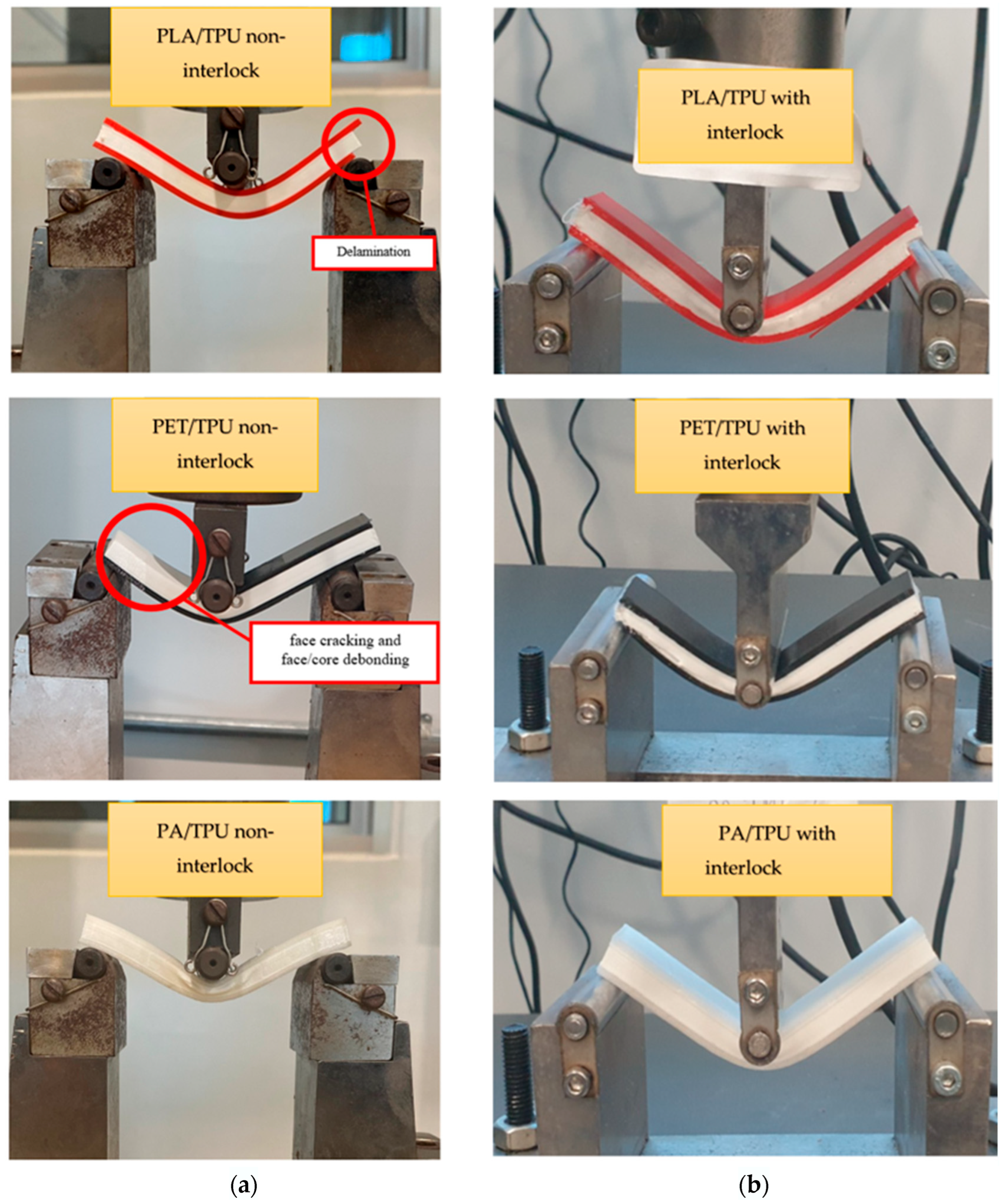

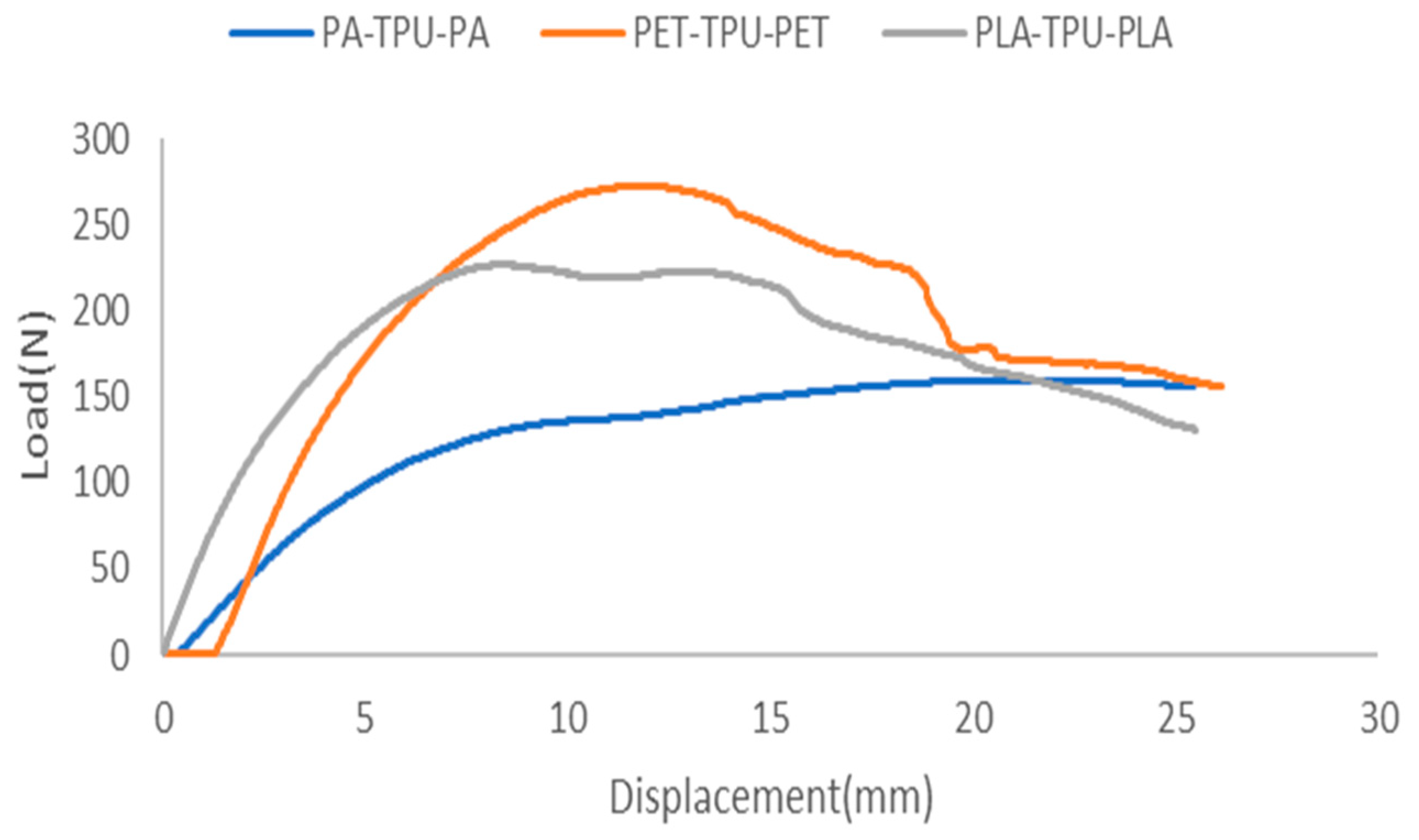

5.1. Non-Interlock Composites Analysis

5.1.1. PA-TPU-PA

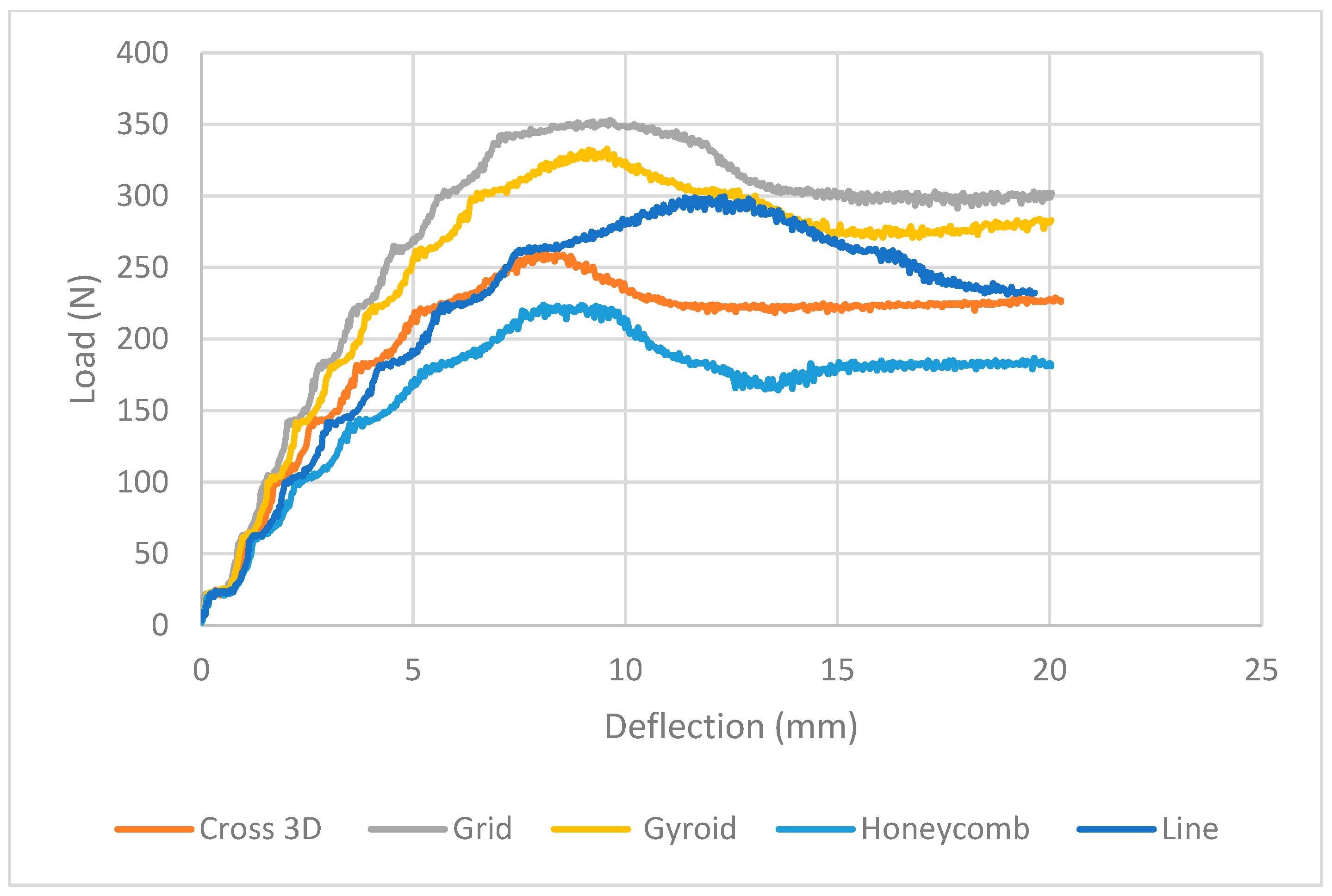

5.1.2. PET-TPU-PET

5.1.3. PLA-TPU-PLA

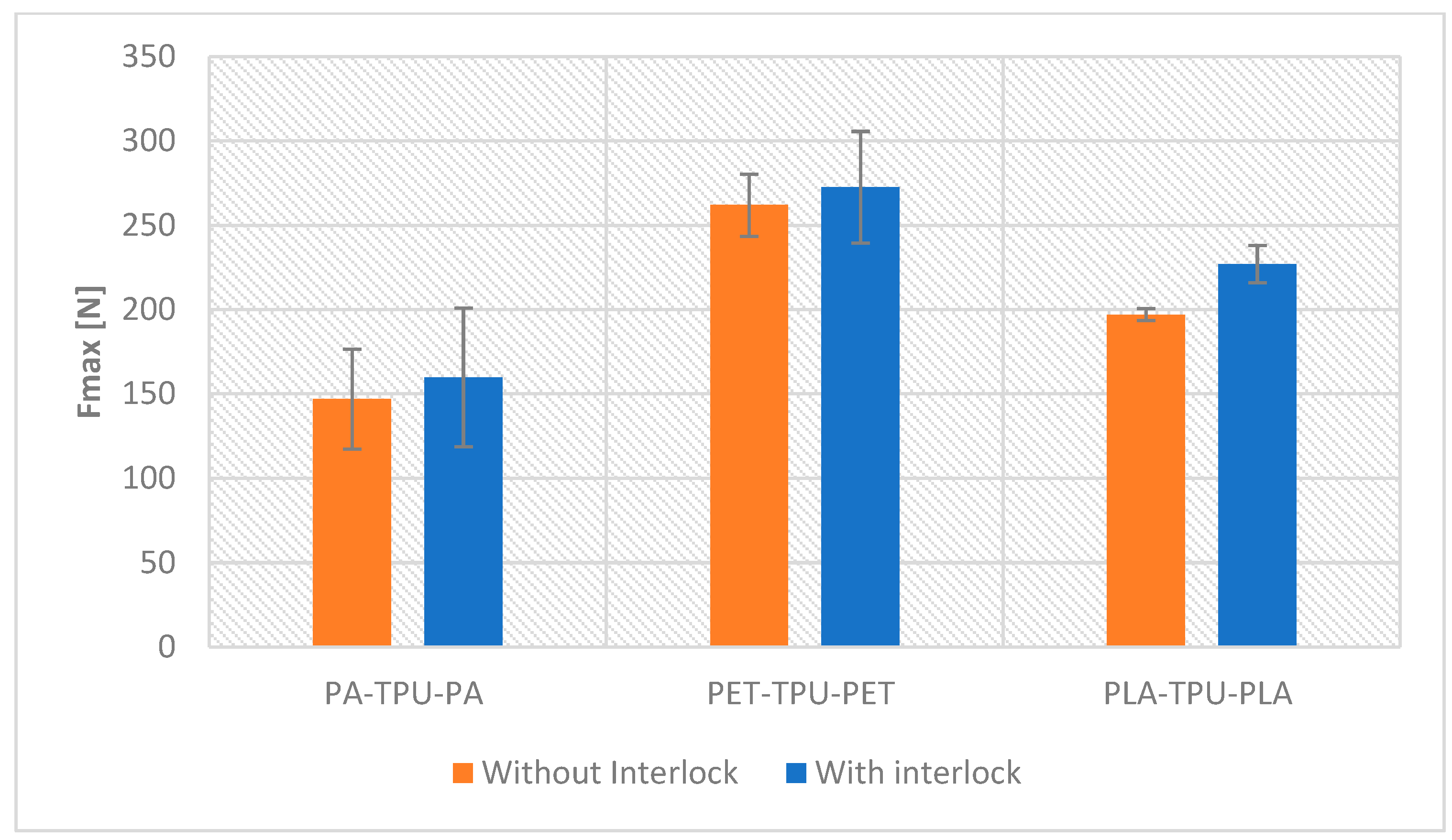

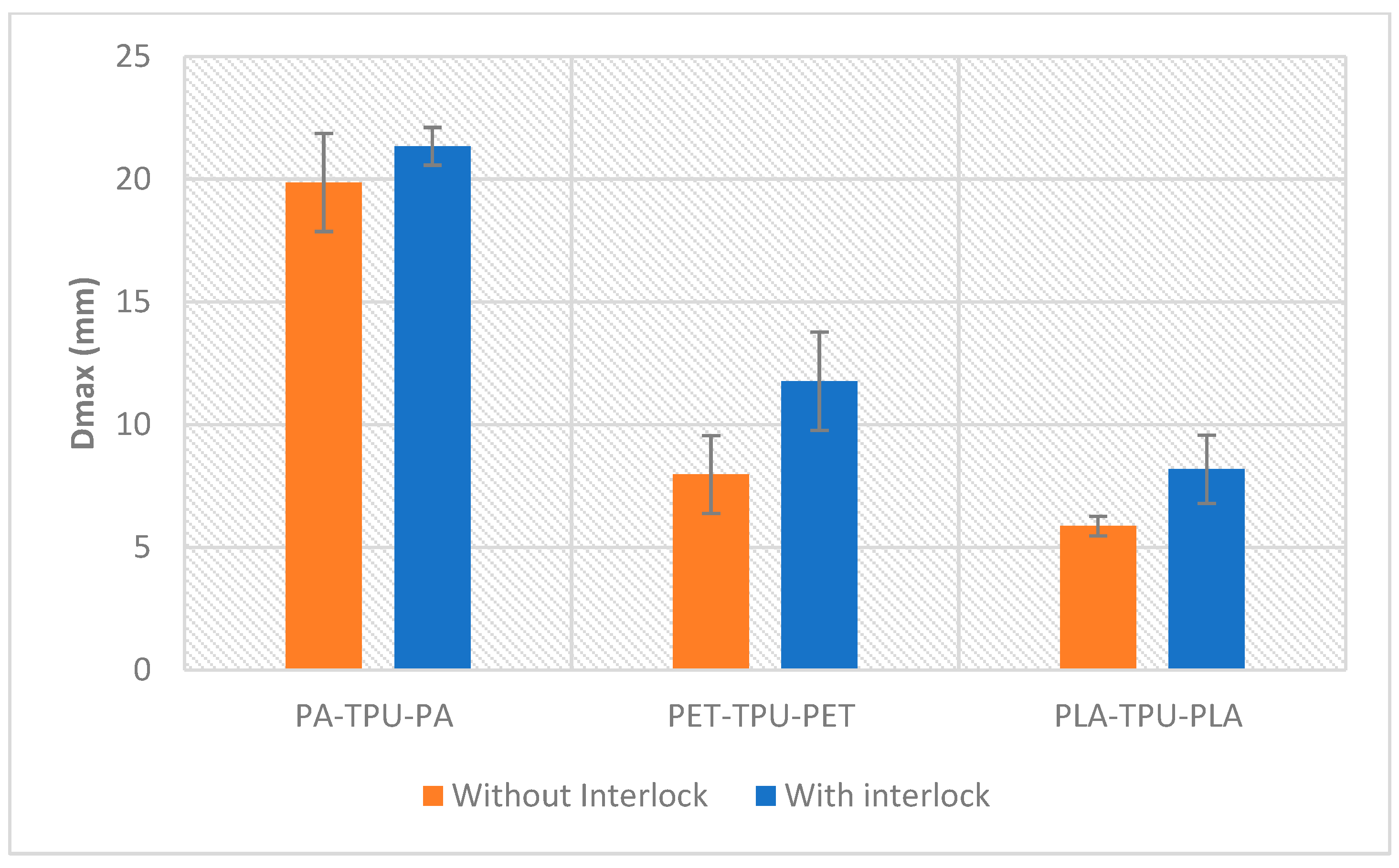

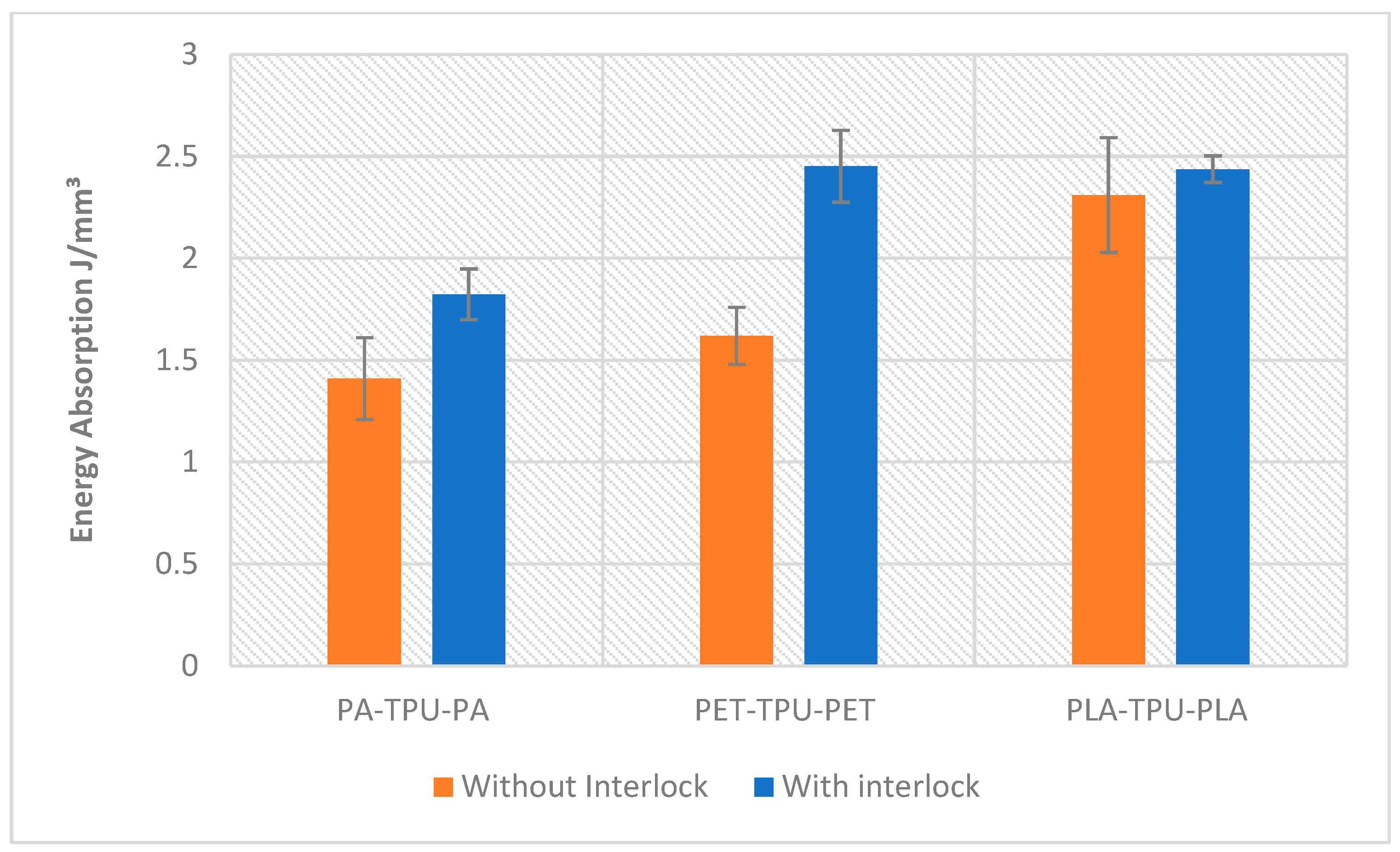

5.2. Comparing Non-Interlock with Interlock Composites (Cross 3D Pattern)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Castro, B.; Magalhães, F.; Panzera, T.; Rubio, J.C.C. An Assessment of Fully Integrated Polymer Sandwich Structures Designed by Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Eng Perform 2021, 30, 5031–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forés-Garriga, A.; Gómez-Gras, G.; Pérez, M.A. Lightweight hybrid composite sandwich structures with additively manufactured cellular cores. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 191, 111082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hu, D. Investigation of Structural Energy Absorption Performance in 3D-Printed Polymer (Tough 1500 Resin) Materials with Novel Multilayer Thin-Walled Sandwich Structures Inspired by Peano Space-Filling Curves. Polymers 2023, 15, 4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardoli, S.; Akhavan Attar, A. Theoretical and experimental investigation of sandwich panels with 3D printed cores with GFRP composite and aluminum face sheets under 3-point bending. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2024, 27, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, S.M.; Enescu, L.A.; Pop, M.A. Mechanical Performances of Lightweight Sandwich Structures Produced by Material Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2020, 12, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fareed, M.I.; Wu, C.; Sood, M. Mechanical characterization of a 3D printed lattice core sandwich structure. Polym. Compos. 2024, 46, 3308–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Liu, W. Multi-objective optimization design of thin-walled sandwich tubes with lateral corrugated tubes for energy absorption. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 137, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, D.; Gordon, A.P.; Yavas, D. Exploring flexural behavior of additively manufactured sandwich beams with bioinspired functionally graded materials. Sci. Rep. 2024, 26, 969–989. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpour, M.; Nejad, S.R.; Mirbagheri, S.M.H. Mechanical and energy absorption properties of multilayered ultra-light sandwich panels produced by 3D-printing and electroforming. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, J.; Zarei, H.R.; Khodamoradi, M.K. Experimental analysis of energy absorption characteristics in composite sandwich structures with 3D-printed honeycomb core under quasi-static compression. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2025, 38, 3891–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlayenko, V.N.; Sadowski, T. Influence of skin/core debonding on free vibration behavior of foam and honeycomb cored sandwich plates. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2010, 45, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragagnolo, G.; Crocombe, A.; Ogin, S.; Mohagheghian, I.; Sordon, A.; Meeks, G.; Santoni, C. Investigation of skin-core debonding in sandwich structures with foam cores. Mater. Des. 2020, 186, 108312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; He, Z.; Li, E.; Tan, X.; Cheng, A.; Li, Q. Energy absorption characteristics of three-layered sandwich panels with graded re-entrant hierarchical honeycomb cores. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursier Niutta, C.; Ciardiello, R.; Tridello, A. Experimental and numerical investigation of a lattice structure for energy absorption: Automotive crash absorber design. Polymers 2022, 14, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geramizadeh, H.; Dariushi, S.; Salami, S.J. Optimal face sheet thickness of 3D printed polymeric hexagonal and re-entrant honeycomb sandwich beams subjected to three-point bending. Compos. Struct. 2022, 291, 115618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvestani, H.Y.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Mirbolghasemi, A.; Hermenean, K. 3D printed meta-sandwich structures: Failure mechanism, energy absorption and multi-hit capability. Mater. Des. 2018, 160, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlochan, F. Sandwich structures for energy absorption applications: A review. Materials 2021, 14, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, T.; Su, R.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.C.L. ITIL: Interlaced Topologically Interlocking Lattice for continuous dual-material extrusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHassan, A.; Ahmed, W.; Zaneldin, E. A Comparative Investigation of the Reliability of Biodegradable Components Produced through Additive Manufacturing Technology. Polymers 2024, 16, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7250/D7250M-20; ASTM International. Standard Practice for Determining Sandwich Beam Flexural and Shear Stiffness. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Bhavikatti, S.S. Finite Element Analysis; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Segerlind, L.J. Applied Finite Element Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jancar, J.; Zarybnicka, K.; Zidek, J.; Kucera, F. Effect of Porosity Gradient on Mechanical Properties of Cellular Nano-Composites. Polymers 2020, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cuitiño, A.M. Three-dimensional nonlinear open-cell foams with large deformations. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2000, 48, 961–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. The Elastic Properties and Yield Strengths of Low-Density Honeycombs and Open-Cell Foams; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Parisien, A.; ElSayed, M.S.A.; Frei, H. Mechanoregulation modelling of stretching versus bending dominated periodic cellular solids. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Han, Y.; Lu, J. Design and optimization of lattice structures: A review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, J. Cellular Ceramics—Structure, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aboelella, M.G.; Ebeid, S.J.; Sayed, M.M. Layer combination of similar infill patterns on the tensile and compression behavior of 3D printed PLA. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunay, M.; Bodur, M.F. Bending behavior of 3D printed polymeric sandwich structures with various types of core topologies. Int. J. Automot. Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Ahmed, S.; Alnajjar, F.; Zaneldin, E. Mechanical performance of three-dimensional printed sandwich composite with a high-flexible core. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2021, 235, 1382–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. The behavior of interlocked ortho-grid composite sandwich structure subjected to low-velocity impact. Compos. Struct. 2023, 304, 116399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, L. Interlocking orthogrid: An efficient way to construct lightweight lattice-core sandwich composite structure. Compos. Struct. 2017, 176, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, S.; Hussain, G.; Ali, A.; Ahmad, H. Mechanical performance of honeycomb sandwich structures built by FDM printing technique. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2021, 36, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, Z.; Hernandez-Nava, E.; Tyas, A.; Warren, J.A.; Fay, S.D.; Goodall, R.; Todd, I.; Askes, H. Energy absorption in lattice structures in dynamics: Experiments. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2016, 89, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composite | Skin Material (Elastic Modulus, Solid) [AA] | Core Material (Effective Elastic Modulus, 20% Infill Density) [Equation (9)] |

|---|---|---|

| PET/TPU | PET (1933 MPa) | TPU (8.2 MPa) |

| PA/TPU | PA (2419 MPa) | |

| PLA/TPU | PLA (2308 MPa) |

| Parameters Used | Settings |

|---|---|

| Printing speed | 1.167 mm/s |

| Temperature of the printing | 205 °C |

| Temperature of the printing bed | 65 °C |

| Height of the printed layer | 0.2 mm |

| Thickness of the wall | 1 mm |

| Thickness of the top layer | 1 mm |

| Thickness of the bottom layer | 1 mm |

| Infill Pattern | Peak Load (N) | Deflection at Peak (mm) | Post-Peak Plateau (N) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid | 220–230 | 9–11 | 175–185 | Highest capacity; steady after initial crest. |

| Line | 180–185 | 11–14 | 170–180 (minor dip near ~19 mm) | Long, flat shoulder → strong energy area. |

| Gyroid | 185–190 | 9–11 | 170–175 | Smooth crest, gentle decline. |

| Cross-3D | 140–145 | 9–12 | 140–145 | Lower but very consistent load. |

| Honeycomb | 110–115 | 8–10 | 100–105 | Softest overall; for low-load uses. |

| Infill Pattern | Peak Load (N) | Deflection at Peak (mm) | Plateau Near 20 mm (N) | Behavior Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid | 350 | 9–10 | 295–300 | Highest crest and sustained load |

| Gyroid | 325–330 | 8–10 | 270–280 | Smooth crest, stable tail |

| Line | 300–310 | 10–12 | 230–240 | Longer shoulder, more softening |

| Cross-3D | 255–265 | 8–9 | 235–245 | Mid/low capacity, steady |

| Honeycomb | 220–225 | 8–9 | 175–185 | Softest; early wall bending |

| Infill Pattern | Peak Load (N)/First Drop (N at mm) | Plateau Level at 15–20 mm (N) | Ductility/Stability (Qual.) | Notes/Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid | 270–280 at 5.5–6 | 120–140 | Moderate softening after peak | Best for high initial stiffness; largest post-peak reduction. |

| Gyroid | 255–265 at 8–9 | 150–170 | Stable plateau, good spread | Good energy absorption with high residual load. |

| Line | 255–265 at 8–9 | 150–165 | Stable plateau, mild softening | Balanced stiffness/ductility; strong large-deflection support. |

| Honeycomb | 215–220 at 8–9 | 130–150 | Smooth response, no sharp drops | Most compliant; predictable but lower strength. |

| Cross-3D | 185–195 at 6 (local drop near 6 mm) | 150–160 | Plateau stable after early event | Early local failure then steady carry; decent residual load. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elhassan, A.; Alhefeiti, H.; Al Karbi, M.; Alseiari, F.; Alshehhi, R.; Ahmed, W.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Al-Mazrouei, N. Enhanced Energy Absorption and Flexural Performance of 3D Printed Sandwich Panels Using Slicer-Generated Interlocking Interfaces. Polymers 2026, 18, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010094

Elhassan A, Alhefeiti H, Al Karbi M, Alseiari F, Alshehhi R, Ahmed W, Al-Marzouqi AH, Al-Mazrouei N. Enhanced Energy Absorption and Flexural Performance of 3D Printed Sandwich Panels Using Slicer-Generated Interlocking Interfaces. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleElhassan, Amged, Hour Alhefeiti, Mdimouna Al Karbi, Fatima Alseiari, Rawan Alshehhi, Waleed Ahmed, Al H. Al-Marzouqi, and Noura Al-Mazrouei. 2026. "Enhanced Energy Absorption and Flexural Performance of 3D Printed Sandwich Panels Using Slicer-Generated Interlocking Interfaces" Polymers 18, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010094

APA StyleElhassan, A., Alhefeiti, H., Al Karbi, M., Alseiari, F., Alshehhi, R., Ahmed, W., Al-Marzouqi, A. H., & Al-Mazrouei, N. (2026). Enhanced Energy Absorption and Flexural Performance of 3D Printed Sandwich Panels Using Slicer-Generated Interlocking Interfaces. Polymers, 18(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010094