Developing Active Modified Starch-Based Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Muña (Minthostachys mollis) Essential Oil Nanoemulsions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Ultrasound-Assisted MEO-NE Preparation

2.3. Optimization of MEO-NE Using I-Optimal Design

2.4. Characterization of MEO-NE

2.4.1. Droplet Size, Polydispersity Index (PDI), and ζ-Potential

2.4.2. DPPH● Method

2.4.3. ABTS●+ Method

2.4.4. pH

2.4.5. Viscosity Measurements

2.4.6. Creaming Stability Analysis

2.4.7. Accelerated Stability Test

2.4.8. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.5. Film Preparation

2.6. Film Characterization

2.6.1. Film’s Appearance and Thickness

2.6.2. Moisture Content (MC) and Solubility in Water (SW)

2.6.3. Water Vapor Permeability (WVP)

2.6.4. Opacity

2.6.5. Contact Angle

2.6.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.6.7. Mechanical Properties

2.6.8. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

DPPH● Test

ABTS●+ Test

2.6.9. Disintegrability Test

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Parameters for Obtaining MEO-NE Using I-Optimal Design

3.2. Characterization of Optimized MEO-NE

3.2.1. Droplet Size, Polydispersity Index (PDI), ζ-Potential, DPPH● Inhibition, and ABTS●+ Inhibition of MEO-NE Under Optimized Conditions

3.2.2. Viscosity and pH of MEO-NE

3.2.3. Creaming Stability Analysis of MEO-NE

3.2.4. Accelerated Centrifugation Test of MEO-NE

3.2.5. Atomic Force Microscopy of MEO-NE

3.3. Composite Films Characterization

3.3.1. Film’s Appearance and Thickness

3.3.2. Moisture Content (MC), Solubility in Water (SW), Water Vapor Permeability (WVP), and Contact Angle (CA)

3.3.3. Mechanical Properties

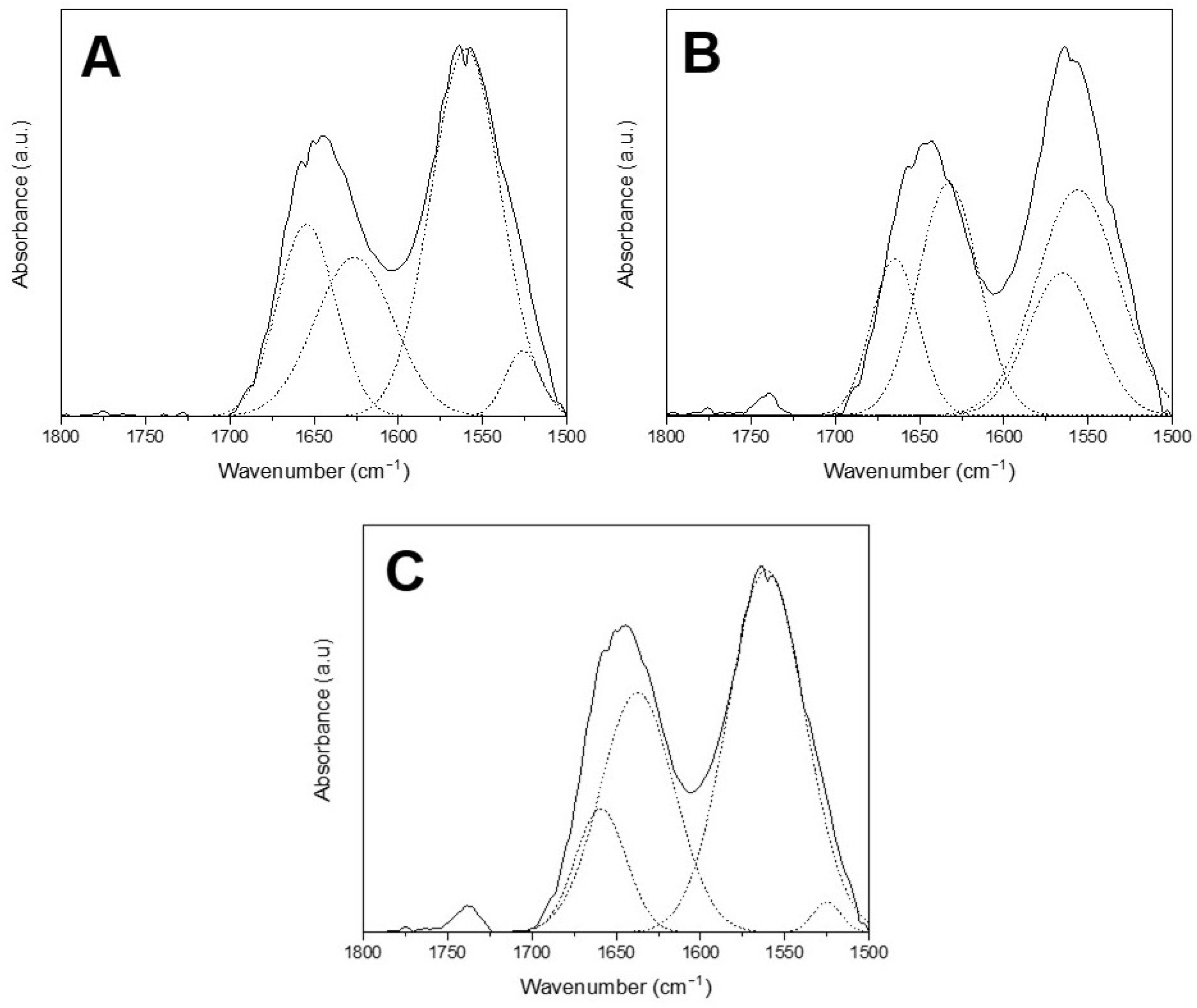

3.3.4. FTIR Analysis of Films

3.3.5. Antioxidant Activity

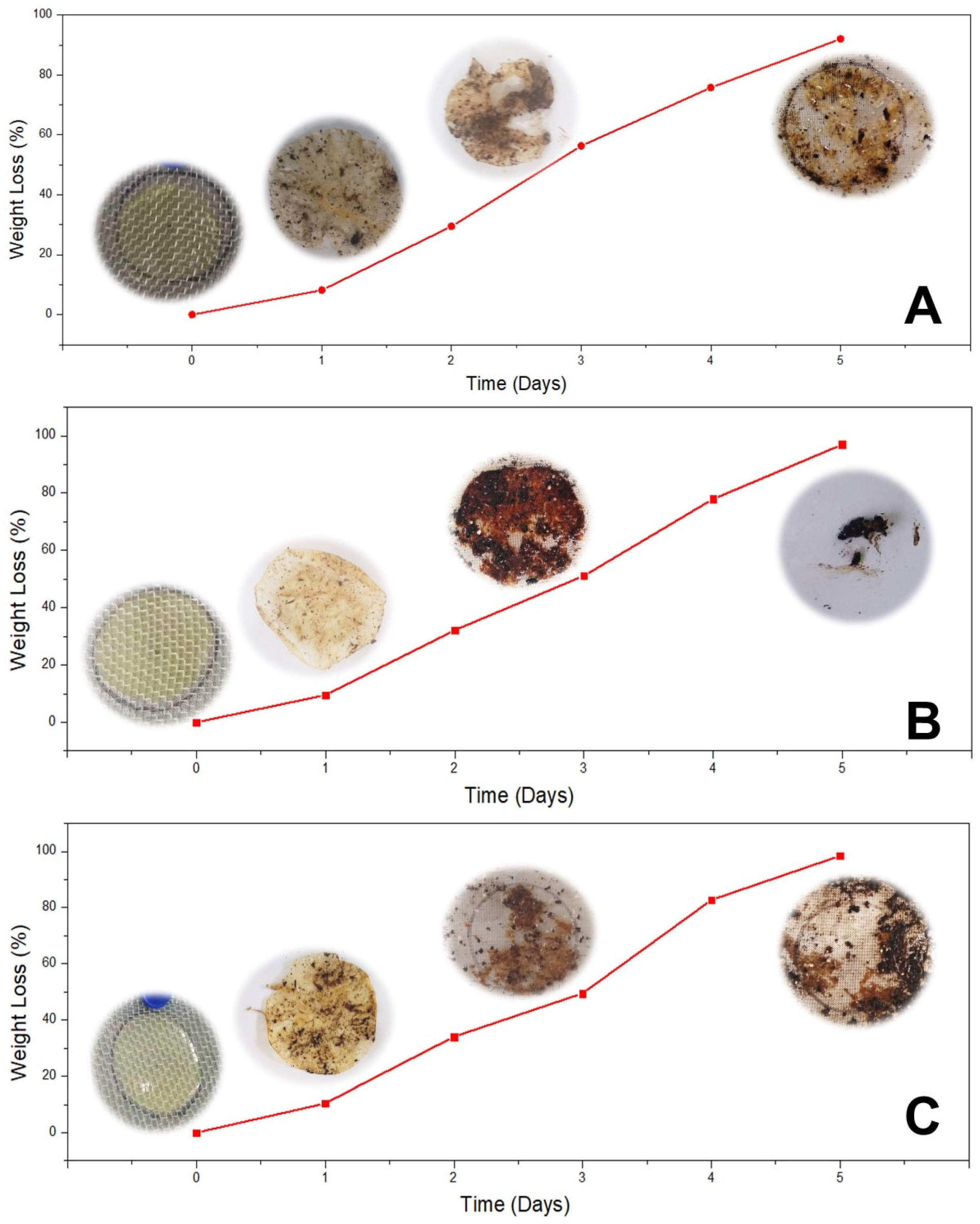

3.3.6. Disintegrability Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xia, X.; Chen, Q.; Liu, H.; Kong, B. Characterization, Release Profile, and Antibacterial Properties of Oregano Essential Oil Nanoemulsions Stabilized by Soy Protein Isolate/Tea Saponin Nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151, 109856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, B.D.; Do Rosário, D.K.A.; Weitz, D.A.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Essential Oil Nanoemulsions: Properties, Development, and Application in Meat and Meat Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 121, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Kang, Y.; He, D.; Yang, B.; Wu, K. Cinnamon Essential Oil Nanoemulsions by High-Pressure Homogenization: Formulation, Stability, and Antimicrobial Activity. LWT 2021, 147, 111660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhong, S.; Schwarz, P.; Chen, B.; Rao, J. Physical Properties, Antifungal and Mycotoxin Inhibitory Activities of Five Essential Oil Nanoemulsions: Impact of Oil Compositions and Processing Parameters. Food Chem. 2019, 291, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, H.A. Using Nanoemulsions of the Essential Oils of a Selection of Medicinal Plants from Jazan, Saudi Arabia, as a Green Larvicidal against Culex Pipiens. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Moreno, W.; Quezada-Torres, W.; Trevez, A.; Arias, G.; Cevallos, E.; Zambrano, Z.; Brito, H.; Salazar, K. Essential oil Minthostachys mollis: Extraction and chemical composition of fresh and stored samples. Arab. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2019, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Tito, J.M.A.; Cartagena-Cutipa, R.; Flores-Valencia, E.; Collantes-Díaz, I. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil from Minthostachys Mollis against Oral Pathogens. Rev. Cuba Estomatol. 2021, 58, e3647. [Google Scholar]

- Dammak, I.; Sobral, P.J.D.A.; Aquino, A.; Neves, M.A.D.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Nanoemulsions: Using Emulsifiers from Natural Sources Replacing Synthetic Ones—A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2721–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, M.; Feng, X.; Wu, X.; Tan, X.; Shang, B.; Huang, Y.; Teng, F.; Li, Y. Characterization and Utilization of Soy Protein Isolate–(−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate–Maltose Ternary Conjugate as an Emulsifier for Nanoemulsions: Enhanced Physicochemical Stability of the β-Carotene Nanoemulsion. Food Chem. 2023, 417, 135842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Erazo, E.M.; Carbajal-Sandoval, M.S.; Sanchez-Pizarro, A.L.; Peña, F.; Martínez, P.; Velezmoro, C. Peruvian Biopolymers (Sapote Gum, Tunta, and Potato Starches) as Suitable Coating Material to Extend the Shelf Life of Bananas. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 2562–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Ugarte, G.A.; López-Malo, A.; Jiménez-Munguía, M.T. Application of Nanoemulsion Technology for Encapsulation and Release of Lipophilic Bioactive Compounds in Food. In Emulsions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Qayum, A.; Liang, Q.; Kang, L.; Raza, H.; Chi, Z.; Chi, R.; Ren, X.; Ma, H. Preparation and Characterization of Ultrasound-Assisted Essential Oil-Loaded Nanoemulsions Stimulated Pullulan-Based Bioactive Film for Strawberry Fruit Preservation. Food Chem. 2023, 422, 136254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsumpun, P.; Iwamoto, S.; Siripatrawan, U. Response Surface Methodology for Optimization of Cinnamon Essential Oil Nanoemulsion with Improved Stability and Antifungal Activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 60, 104604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Wang, C.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Kong, F.; Bi, Y. Preparation, Characterization and Properties of Cinnamon Essential Oil Nano-Emulsion Formed by Different Emulsifiers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 86, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tian, G.; Qu, H. Application of I-Optimal Design for Modeling and Optimizing the Operational Parameters of Ibuprofen Granules in Continuous Twin-Screw Wet Granulation. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilela, C.; Kurek, M.; Hayouka, Z.; Röcker, B.; Yildirim, S.; Antunes, M.D.C.; Nilsen-Nygaard, J.; Pettersen, M.K.; Freire, C.S.R. A Concise Guide to Active Agents for Active Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Santos, R.; Andrade, M.; Melo, N.R.D.; Sanches-Silva, A. Use of Essential Oils in Active Food Packaging: Recent Advances and Future Trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 61, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Lu, J.; Huang, H.; Gao, X.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, W. Four Types of Winged Yam (Dioscorea Alata L.) Resistant Starches and Their Effects on Ethanol-Induced Gastric Injury in Vivo. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 85, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelyazkov, S.; Zsivanovits, G.; Stamenova, E.; Marudova, M. Physical and Barrier Properties of Clove Essential Oil Loaded Potato Starch Edible Films. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 12, 4603–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ma, Q.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, J. Development of Chitosan/Potato Peel Polyphenols Nanoparticles Driven Extended-Release Antioxidant Films Based on Potato Starch. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavareze, E.D.R.; Pinto, V.Z.; Klein, B.; El Halal, S.L.M.; Elias, M.C.; Prentice-Hernández, C.; Dias, A.R.G. Development of Oxidised and Heat–Moisture Treated Potato Starch Film. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Betalleluz-Pallardel, I.; Cuba, A.; Peña, F.; Cervantes-Uc, J.M.; Uribe-Calderón, J.A.; Velezmoro, C. Effects of Natural Freeze-Thaw Treatment on Structural, Functional, and Rheological Characteristics of Starches Isolated from Three Bitter Potato Cultivars from the Andean Region. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 132, 107860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Sánchez-Pizarro, A.; Vélez-Erazo, E.M.; Peña-Carrasco, E.F.; Pasquel-Reátegui, J.L.; Martínez-Tapia, P.; Velezmoro-Sánchez, C. Bitter Potato Starch-based Film Enriched with Copaiba Leaf Extract Obtained Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide: Physical–Mechanical, Antioxidant, and Disintegrability Properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Fabrication, Structure and Properties of Pullulan-Based Active Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Cinnamon Essential Oil Nanoemulsions. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 25, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsara, O.; Jafari, S.M.; Muhidinov, Z.K. Fabrication, Characterization and Stability of Oil in Water Nano-Emulsions Produced by Apricot Gum-Pectin Complexes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Norton, I.T.; Batchelor, H.K.; Gkatzionis, K.; Spyropoulos, F.; Sobral, P.J.A. Physico-Chemical, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Gelatin-Chitosan Based Films Loaded with Nanoemulsions Encapsulating Active Compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Method of Analysis, 22nd ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Elaissari, A.; Ghnimi, S.; Dumas, E.; Gharsallaoui, A. Effect of Pectin on the Properties of Nanoemulsions Stabilized by Sodium Caseinate at Neutral pH. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 1858–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felipe, L.D.O.; Bicas, J.L.; Changwatchai, T.; Abah, E.O.; Nakajima, M.; Neves, M.A. Physical Stability of α-Terpineol-Based Nanoemulsions Assessed by Direct and Accelerated Tests Using Photo Centrifuge Analysis. LWT 2024, 205, 116513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, K.C.S.; Vicente, A.A.; Sobral, P.J.A. Development, Characterization, and Stability of O/W Pepper Nanoemulsions Produced by High-Pressure Homogenization. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condés, M.C.; Añón, M.C.; Mauri, A.N.; Dufresne, A. Amaranth Protein Films Reinforced with Maize Starch Nanocrystals. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 47, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.-Y.; Tang, M.-Q.; Gao, Q.; Wang, X.-W.; Zhang, J.-W.; Tanokura, M.; Xue, Y.-L. Effects of Different Modification Methods on the Physicochemical and Rheological Properties of Chinese Yam (Dioscorea opposita Thunb.) Starch. LWT 2019, 116, 108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessaro, L. Produção de Emulsão Dupla A/O/A Rica Em Extrato de Folha de Pitangueira (Eugenia uniflora L.) Para Aplicação Em Filmes Ativos de Gelatina e/ou Quitosana. Master’s Dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, Pirassununga, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 20200:2015; Plastics—Determination of the Degree of Disintegration of Plastic Materials Under Simulated Composting Conditions in a Laboratory-Scale Test. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Goswaim, T.H.; Maiti, M.M. Biodegradability of Gelatin—PF Resin Blends by Soil Burial Method. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1998, 61, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Costa, A.L.R.; Cunha, R.L. Impact of Oil Type and WPI/Tween 80 Ratio at the Oil-Water Interface: Adsorption, Interfacial Rheology and Emulsion Features. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 164, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, O.; Saricaoglu, F.T.; Besir, A.; Atalar, I.; Yazici, F. Effect of Ultrasound Treatment on the Properties of Nano-Emulsion Films Obtained from Hazelnut Meal Protein and Clove Essential Oil. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 41, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tastan, Ö.; Ferrari, G.; Baysal, T.; Donsì, F. Understanding the Effect of Formulation on Functionality of Modified Chitosan Films Containing Carvacrol Nanoemulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 61, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.-J.; Chu, B.-S.; Kobayashi, I.; Nakajima, M. Performance of Selected Emulsifiers and Their Combinations in the Preparation of β-Carotene Nanodispersions. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Food Emulsions: Principles, Practices, and Techniques, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cen, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C.; Fu, L. Nano-Emulsification Improves Physical Properties and Bioactivities of Litsea Cubeba Essential Oil. LWT 2021, 137, 110361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions versus Microemulsions: Terminology, Differences, and Similarities. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Barati, A. Essential Oils Nanoemulsions: Preparation, Characterization and Study of Antibacterial Activity against Escherichia Coli. Int. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 15, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gorjian, H.; Mihankhah, P.; Khaligh, N.G. Influence of Tween Nature and Type on Physicochemical Properties and Stability of Spearmint Essential Oil (Mentha spicata L.) Stabilized with Basil Seed Mucilage Nanoemulsion. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 359, 119379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, N.S.; Cravero, C.F.; Grosso, N.R.; Olmedo, R.H. Pulegone/MENT Ratio as an Indicator of Antioxidant Activity for the Selection of Industrial Cultivars of Peperina with High Antioxidant Potential. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 216, 118770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, T.N.; De Holanda E Silva, K.G. Nanoemulsions of Essential Oils to Improve Solubility, Stability and Permeability: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1153–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, G.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Cao, J.; Zhang, L. Effects of Glycerol Monostearate and Tween 80 on the Physical Properties and Stability of Recombined Low-Fat Dairy Cream. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2016, 96, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, T. Emulsion Formation, Stability, and Rheology. In Emulsion Formation and Stability; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dammak, I.; Sobral, P.J.D.A. Effect of Different Biopolymers on the Stability of Hesperidin-Encapsulating O/W Emulsions. J. Food Eng. 2018, 237, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammak, I.; Do Amaral Sobral, P.J. Investigation into the Physicochemical Stability and Rheological Properties of Rutin Emulsions Stabilized by Chitosan and Lecithin. J. Food Eng. 2018, 229, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsasso, R.R.; Cesca, K.; Valencia, G.A.; Monteiro, A.R.; Zhang, Z.J.; Fryer, P.J. Active Films Produced Using Ginger Oleoresin Nanoemulsion: Characterization and Application on Mozzarella Cheese. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 167, 111394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yin, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Qiu, W. Enhancing Bread Preservation through Non-Contact Application of Starch-Based Composite Film Infused with Clove Essential Oil Nanoemulsion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Ma, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, J. Preparation and Characterization of Biodegradable Composited Films Based on Potato Starch/Glycerol/Gelatin. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 6633711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez, M.; Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Active Packaging Film of Chitosan and Santalum Album Essential Oil: Characterization and Application as Butter Sachet to Retard Lipid Oxidation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 34, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, N. Effects of Grape Seed Oil Nanoemulsion on Physicochemical and Antibacterial Properties of Gelatin-sodium Alginate Film Blends. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 237, 124207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, C.; Shenoy, R.; Shetty, P.; Srinivasulu, M.; Nayak, R. Formulation and Characterization of Starch-Based Novel Biodegradable Edible Films for Food Packaging. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 2858–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, I.B.; Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, S. Chitosan-Based Composite Films Containing Eugenol Nanoemulsion, ZnO Nanoparticles and Aloe Vera Gel for Active Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Li, F.; Zhou, X.; Lu, C.; Zhang, T. Characterization and Sustained Release Study of Starch-Based Films Loaded with Carvacrol: A Promising UV-Shielding and Bioactive Nanocomposite Film. LWT 2023, 180, 114719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Peña, F.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Núñez-Santiago, C.; Yee-Madeira, H.; Velezmoro, C. Physicochemical, Functional and Morphological Characterization of Starches Isolated from Three Native Potatoes of the Andean Region. Food Chem. X 2019, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylan, O.; Cebi, N.; Sagdic, O. Rapid Screening of Mentha Spicata Essential Oil and L-Menthol in Mentha Piperita Essential Oil by ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Coupled with Multivariate Analyses. Foods 2021, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emadian, S.M.; Onay, T.T.; Demirel, B. Biodegradation of Bioplastics in Natural Environments. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Li, M.; Gong, X.; Niu, B.; Li, W. Biodegradable and Antimicrobial CSC Films Containing Cinnamon Essential Oil for Preservation Applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.; Sobral, P.J.A. Disintegrability under Composting Conditions of Films Based on Gelatin, Chitosan and/or Sodium Caseinate Containing Boldo-of-Chile Leafs Extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent Variable | Type | Levels | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Emulsifier concentration (%, w/w) | Numeric | 6 | 10 |

| Essential oil concentration (%, w/w) | Numeric | 3 | 6 |

| Sonication time (min) | Numeric | 9 | 15 |

| Emulsifier | Categorical | Tween® 80 | Sapote gum |

| Run | Factors | Responses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |

| 1 | 9.68 | 12.0 | 4.44 | Tween® 80 | 13.96 ± 0.88 | −21.10 ± 0.52 | 91.20 ± 0.54 |

| 2 | 10.00 | 9.0 | 3.00 | Tween® 80 | 11.89 ± 0.63 | −18.06 ± 2.67 | 88.98 ± 0.49 |

| 3 | 6.00 | 9.0 | 3.87 | Tween® 80 | 89.44 ± 26.16 | −22.40 ± 3.08 | 89.57 ± 0.37 |

| 4 | 10.00 | 9.0 | 4.93 | Tween® 80 | 17.69 ± 3.28 | −24.23 ± 4.86 | 91.81 ± 0.38 |

| 5 | 8.30 | 9.0 | 4.04 | Sapote gum | 687.96 ± 15.40 | −27.63 ± 0.21 | 70.97 ± 1.08 |

| 6 | 7.72 | 15.0 | 3.02 | Tween® 80 | 129.02 ± 9.18 | −22.26 ± 4.18 | 88.35 ± 0.36 |

| 7 | 6.00 | 13.0 | 5.78 | Tween® 80 | 24.13 ± 3.12 | −20.33 ± 0.45 | 93.13 ± 0.36 |

| 8 | 9.90 | 11.0 | 3.00 | Sapote gum | 414.46 ± 28.22 | −26.80 ± 0.40 | 68.22 ± 0.33 |

| 9 | 6.10 | 15.0 | 4.65 | Sapote gum | 429.26 ± 41.97 | −27.56 ± 1.09 | 73.12 ± 0.37 |

| 10 | 9.92 | 15.0 | 4.93 | Sapote gum | 579.23 ± 82.54 | −27.16 ± 0.37 | 75.01 ± 0.60 |

| 11 | 6.08 | 11.0 | 3.00 | Sapote gum | 708.56 ± 237.43 | −29.53 ± 0.15 | 70.35 ± 1.11 |

| 12 | 6.00 | 9.0 | 6.00 | Sapote gum | 746.13 ± 46.39 | −28.60 ± 0.26 | 76.81 ± 2.37 |

| 13 | 7.92 | 11.0 | 3.00 | Tween® 80 | 12.98 ± 0.77 | −16.46 ± 0.66 | 89.07 ± 0.87 |

| 14 | 9.68 | 12.0 | 4.44 | Tween® 80 | 16.23 ± 2.12 | −17.03 ± 1.90 | 81.39 ± 1.61 |

| 15 | 8.30 | 9.0 | 4.04 | Sapote gum | 506.73 ± 130.58 | −28.20 ± 0.17 | 73.37 ± 0.26 |

| 16 | 10.00 | 15.0 | 6.00 | Tween® 80 | 23.43 ± 3.47 | −13.70 ± 0.80 | 86.53 ± 1.33 |

| 17 | 6.60 | 15.0 | 3.00 | Sapote gum | 608.83 ± 89.65 | −28.53 ± 0.45 | 84.02 ± 1.45 |

| 18 | 10.00 | 14.0 | 3.09 | Sapote gum | 501.60 ± 16.77 | −27.53 ± 0.21 | 80.85 ± 0.68 |

| 19 | 8.30 | 13.0 | 5.85 | Sapote gum | 650.80 ± 8.88 | −27.90 ± 0.45 | 87.38 ± 0.29 |

| 20 | 9.68 | 12.0 | 4.44 | Tween® 80 | 13.69 ± 0.21 | −19.06 ± 2.54 | 92.34 ± 0.48 |

| 21 | 8.28 | 9.0 | 6.00 | Tween® 80 | 20.09 ± 1.08 | −18.40 ± 1.08 | 94.34 ± 0.08 |

| 22 | 6.00 | 13.0 | 5.78 | Tween® 80 | 31.40 ± 1.06 | −18.30 ± 1.35 | 94.12 ± 3.27 |

| 23 | 10.00 | 9.0 | 6.00 | Sapote gum | 763.33 ± 78.37 | −27.40 ± 0.17 | 82.72 ± 0.27 |

| 24 | 8.30 | 13.0 | 5.85 | Sapote gum | 691.53 ± 60.13 | −27.76 ± 0.35 | 86.31 ± 0.28 |

| Term | Droplet Size (nm) | ζ-Potential (mV) | DPPH Inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 30.29 ** | 7.66 * | 5.67 * |

| X1—Emulsifier concentration (%) | 1.77 | 2.23 | 0.0489 |

| X2—Sonication time (min) | 1.59 | 0.7830 | 0.7524 |

| X3—Essential oil concentration (%) | 0.5799 | 0.7969 | 6.27 * |

| X4—Type of emulsifier | 310.84 ** | 74.27 ** | 42.54 ** |

| X1×2 | 0.7518 | 0.3213 | 0.7236 |

| X1X3 | 5.04 * | 0.1252 | 0.0325 |

| X1X4 | 0.0007 | 0.3182 | 1.23 |

| X2X3 | 1.29 | 3.27 | 2.14 |

| X2X4 | 1.41 | 0.2098 | 3.10 |

| X3X4 | 4.71 | 0.3174 | 1.24 |

| X12 | 0.2473 | 0.4038 | |

| X22 | 0.2323 | 0.0734 | |

| X32 | 1.37 | 2.65 | |

| Lack of fit | 2.08 | 3.73 | 1.79 |

| R2 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.81 |

| Characteristics | Predicted | Experimental |

|---|---|---|

| Droplet size (nm) | 54.3 | 48.6 ± 2.5 |

| ζ-potential (mV) | −22.1 | −15.0 ± 1.17 |

| DPPH● inhibition (%) | 93.1 | 95.6 ± 0.08 |

| ABTS●+ inhibition (%) | -- | 89.6 ± 0.70 |

| PDI | -- | 0.223 ± 0.00 |

| Viscosity (mPa·s) | -- | 1 ± 0 |

| pH | -- | 4.1 ± 0.01 |

| Sample | Thickness (mm) | Moisture Content (%) | Solubility in Water (%) | WVP × 10−10 (g·m−1 s−1 Pa−1) | Contact Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | 0.112 ± 0.005 a | 13.43 ± 0.48 c | 72.53 ± 2.25 c | 1.17 ± 0.06 b | 67.88 ± 0.56 a |

| F1 | 0.114 ± 0.007 a | 8.56 ± 0.36 a | 60.56 ± 0.57 b | 0.93 ± 0.05 a | 72.11 ± 0.80 b |

| F2 | 0.114 ± 0.003 a | 9.52 ± 0.49 b | 45.33 ± 0.18 a | 0.89 ± 0.05 a | 75.76 ± 0.26 c |

| Sample | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Yield (%) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F0 | 12.58 ± 0.05 a | 4.17 ± 0.06 b | 610.62 ± 13.07 a |

| F1 | 30.71 ± 0.63 c | 3.78 ± 0.05 a | 1425.82 ± 10.92 c |

| F2 | 15.75 ± 0.33 b | 3.59 ± 0.18 a | 786.45 ± 18.48 b |

| Sample | F0 | F1 | F2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1 | 1654 | 1665 | 1659 |

| Peak 2 | 1626 | 1633 | 1637 |

| Peak 3 | 1560 | 1565 | 1561 |

| Peak 4 | 1526 | 1556 | 1525 |

| Sample | DPPH● (% Inhibition) | ABTS●+ Radical (% Inhibition) |

|---|---|---|

| F0 | 9.8 ± 0.88 a | 13.92 ± 0.04 a |

| F1 | 53.9 ± 1.49 b | 28.46 ± 2.11 b |

| F2 | 59.2 ± 1.02 c | 43.05 ± 2.06 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Flores-Bao, J.A.; Pérez-Córdoba, L.J.; Martínez-Tapia, P.; Peña-Carrasco, F.; Sobral, P.J.d.A.; Moraes, I.F.; Velezmoro-Sánchez, C. Developing Active Modified Starch-Based Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Muña (Minthostachys mollis) Essential Oil Nanoemulsions. Polymers 2026, 18, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010023

Flores-Bao JA, Pérez-Córdoba LJ, Martínez-Tapia P, Peña-Carrasco F, Sobral PJdA, Moraes IF, Velezmoro-Sánchez C. Developing Active Modified Starch-Based Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Muña (Minthostachys mollis) Essential Oil Nanoemulsions. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores-Bao, José Antonio, Luis Jaime Pérez-Córdoba, Patricia Martínez-Tapia, Fiorela Peña-Carrasco, Paulo José do Amaral Sobral, Izabel Freitas Moraes, and Carmen Velezmoro-Sánchez. 2026. "Developing Active Modified Starch-Based Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Muña (Minthostachys mollis) Essential Oil Nanoemulsions" Polymers 18, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010023

APA StyleFlores-Bao, J. A., Pérez-Córdoba, L. J., Martínez-Tapia, P., Peña-Carrasco, F., Sobral, P. J. d. A., Moraes, I. F., & Velezmoro-Sánchez, C. (2026). Developing Active Modified Starch-Based Films Incorporated with Ultrasound-Assisted Muña (Minthostachys mollis) Essential Oil Nanoemulsions. Polymers, 18(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010023