PLA-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Synthesis to the Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. PLA Synthesis

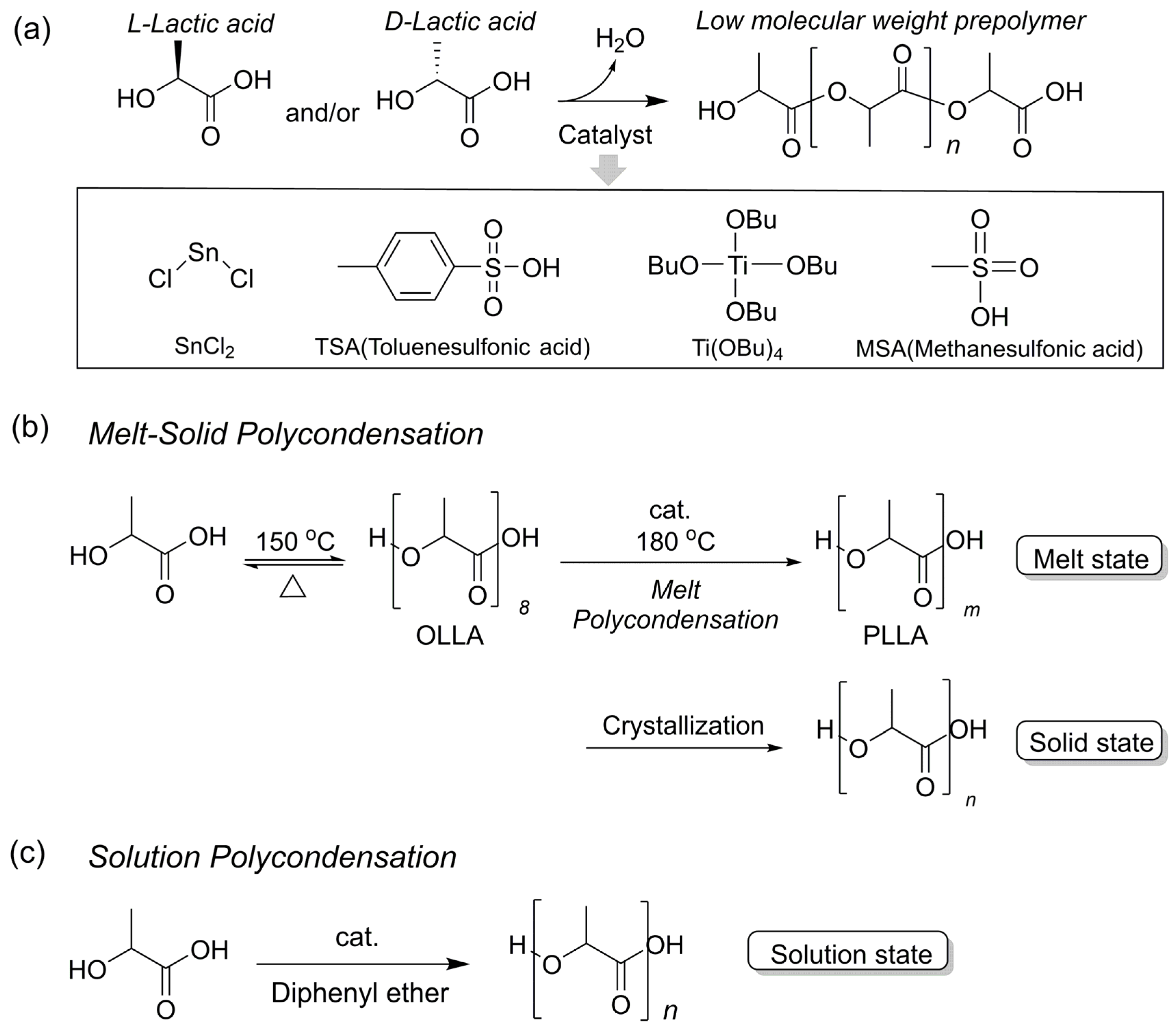

2.1. Polycondensation

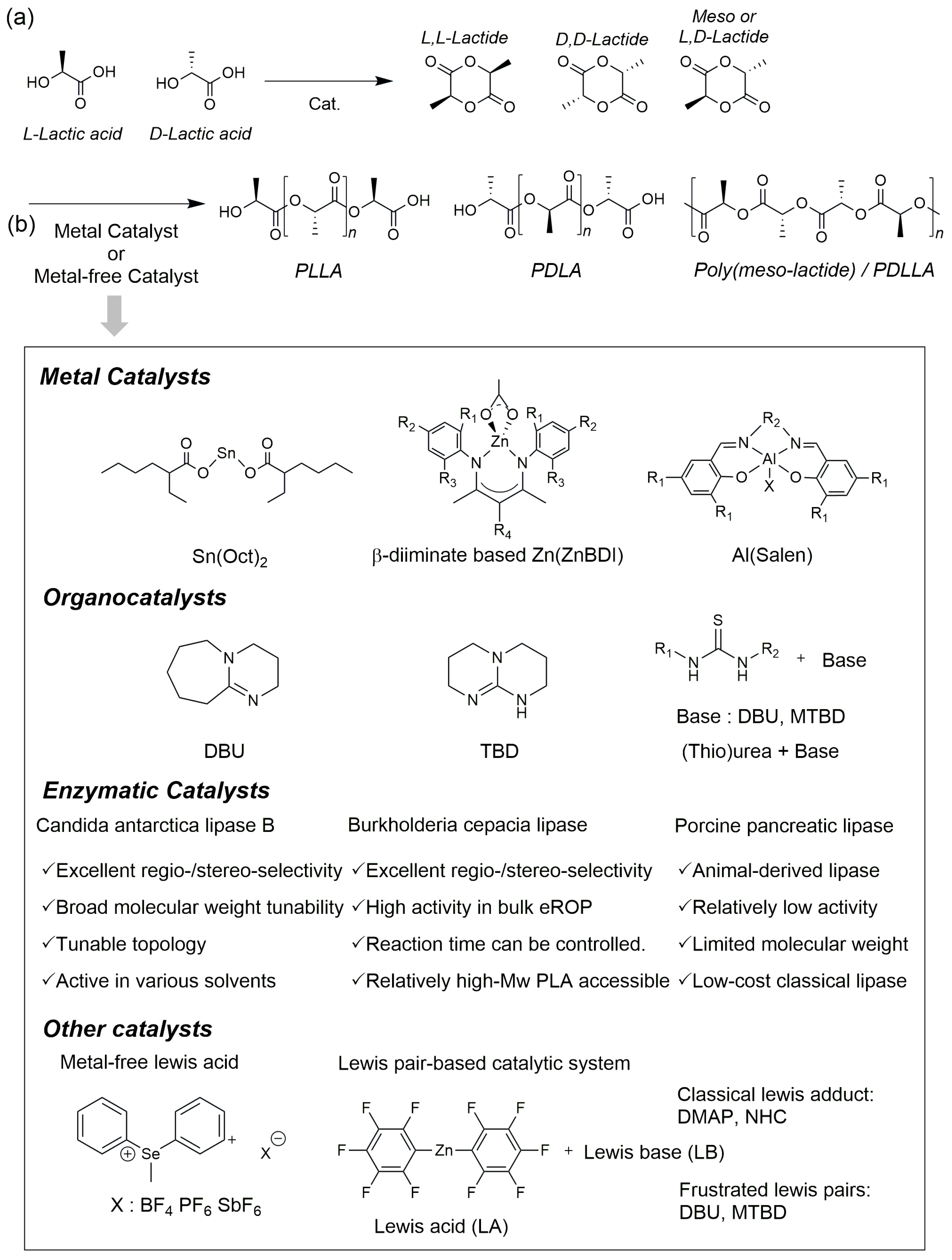

2.2. Ring-Opening Polymerization (ROP)

2.2.1. ROP Using Metal Catalysts

2.2.2. ROP Using Organic Catalysts

2.2.3. ROP Using Enzyme Catalysts

2.2.4. Other Catalysts

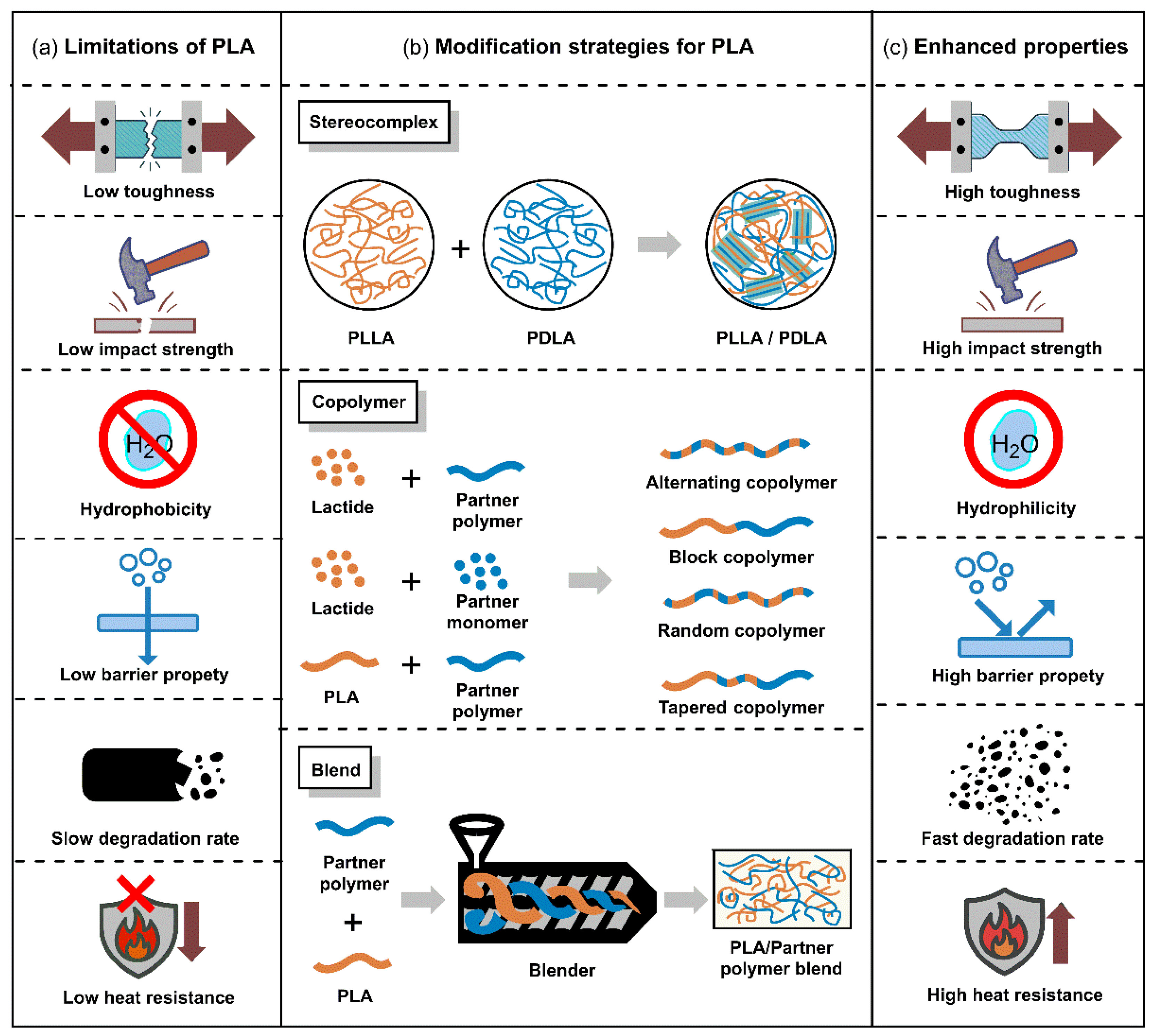

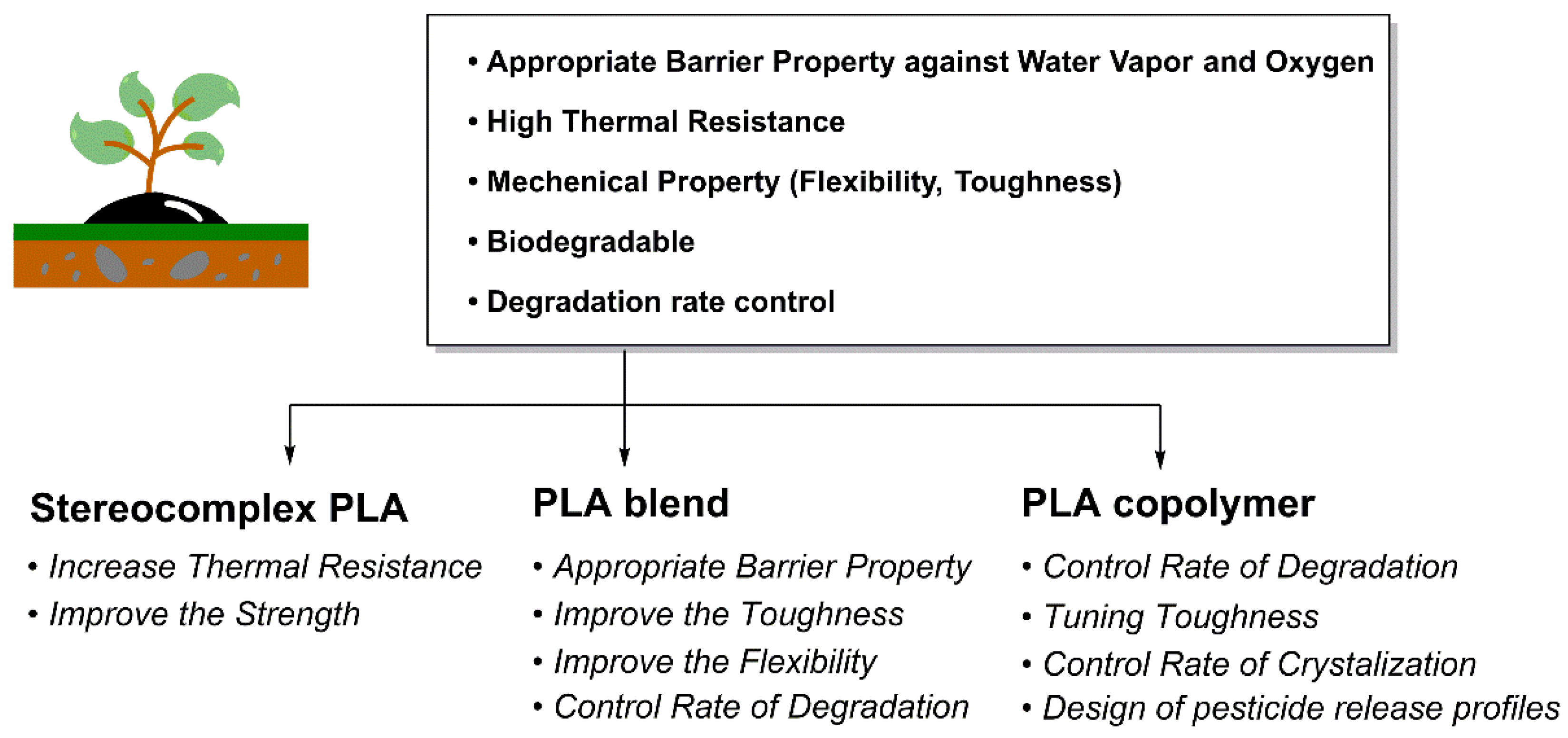

3. Tunable Physical and Biodegradable Properties of PLA

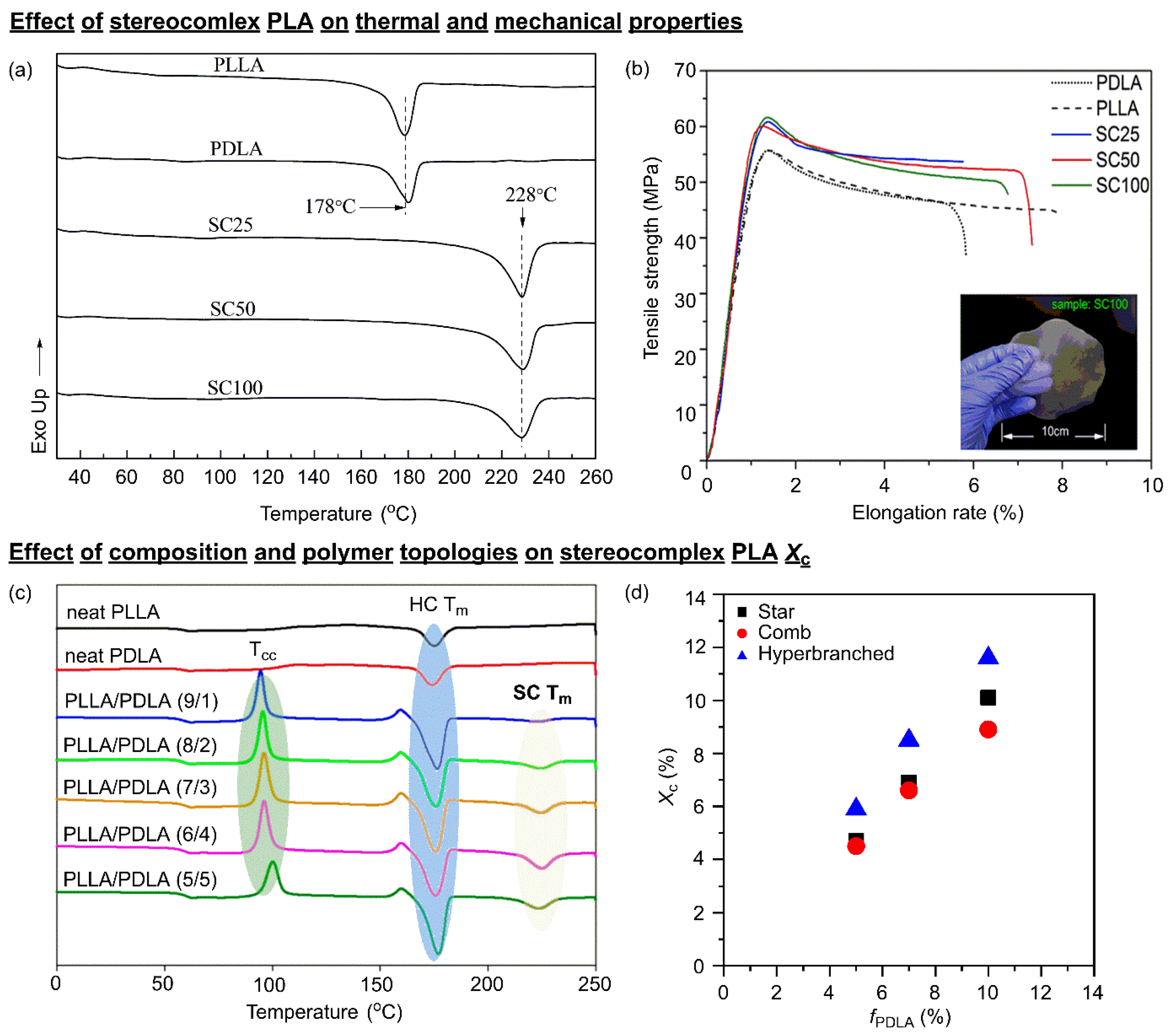

3.1. SC PLA

3.2. PLA Blend

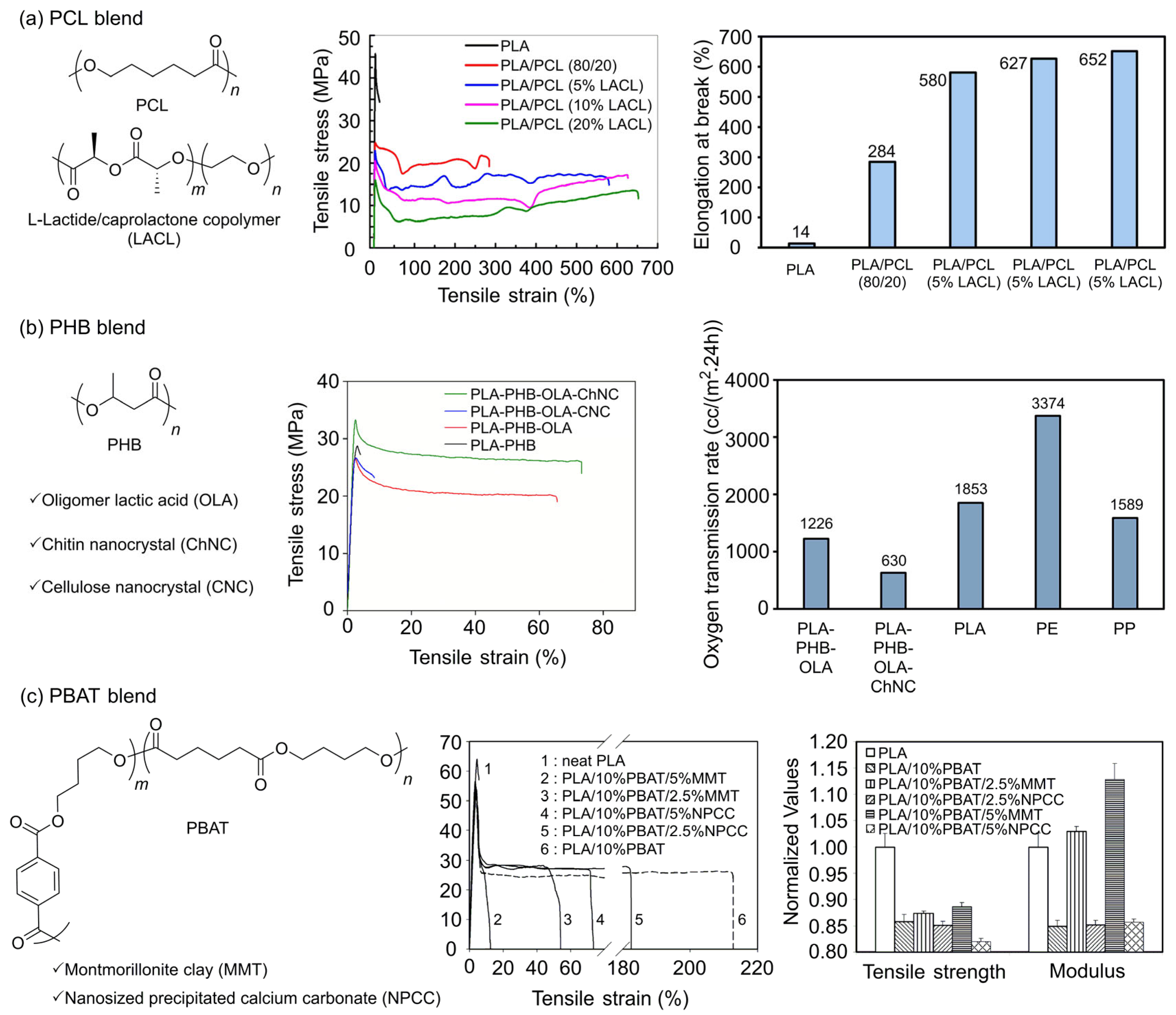

3.2.1. PLA/PCL Blend

3.2.2. PLA/PHB Blend

3.2.3. PLA/PBAT Blend

3.3. PLA Copolymer

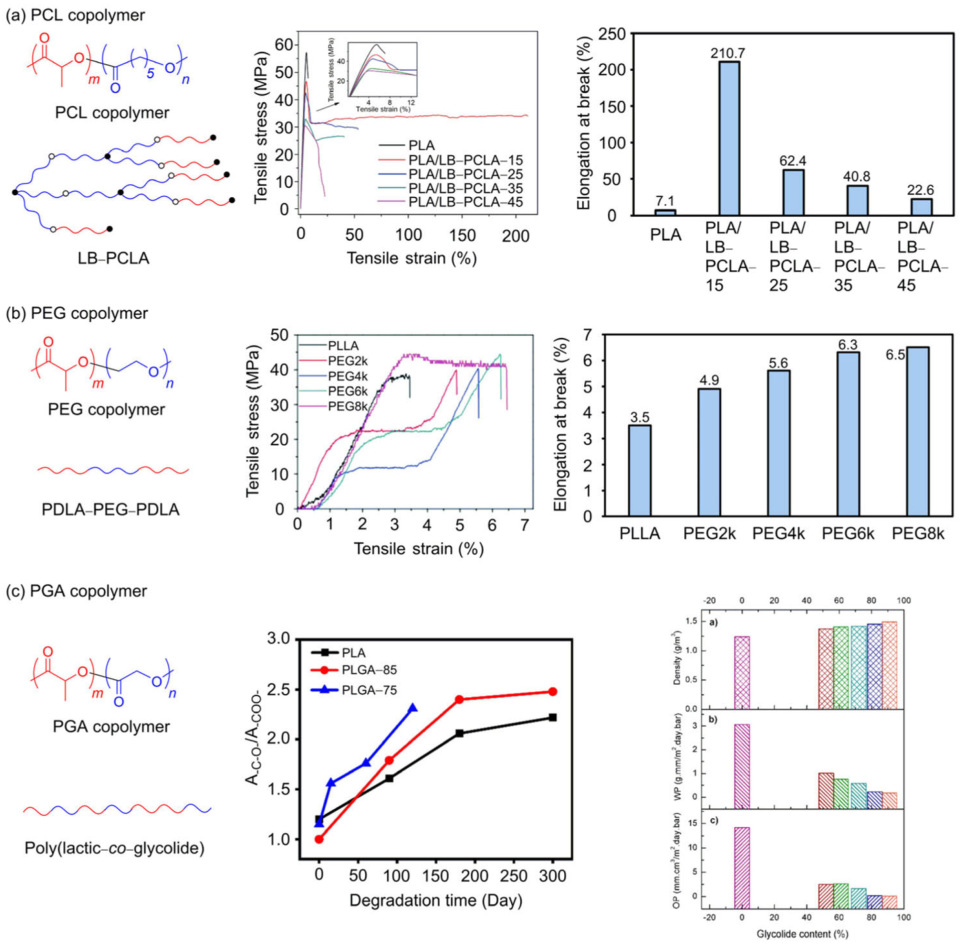

3.3.1. PLA/PCL Copolymer

3.3.2. PLA/PEG Copolymer

3.3.3. PLA/PGA Copolymer

4. Application of PLA

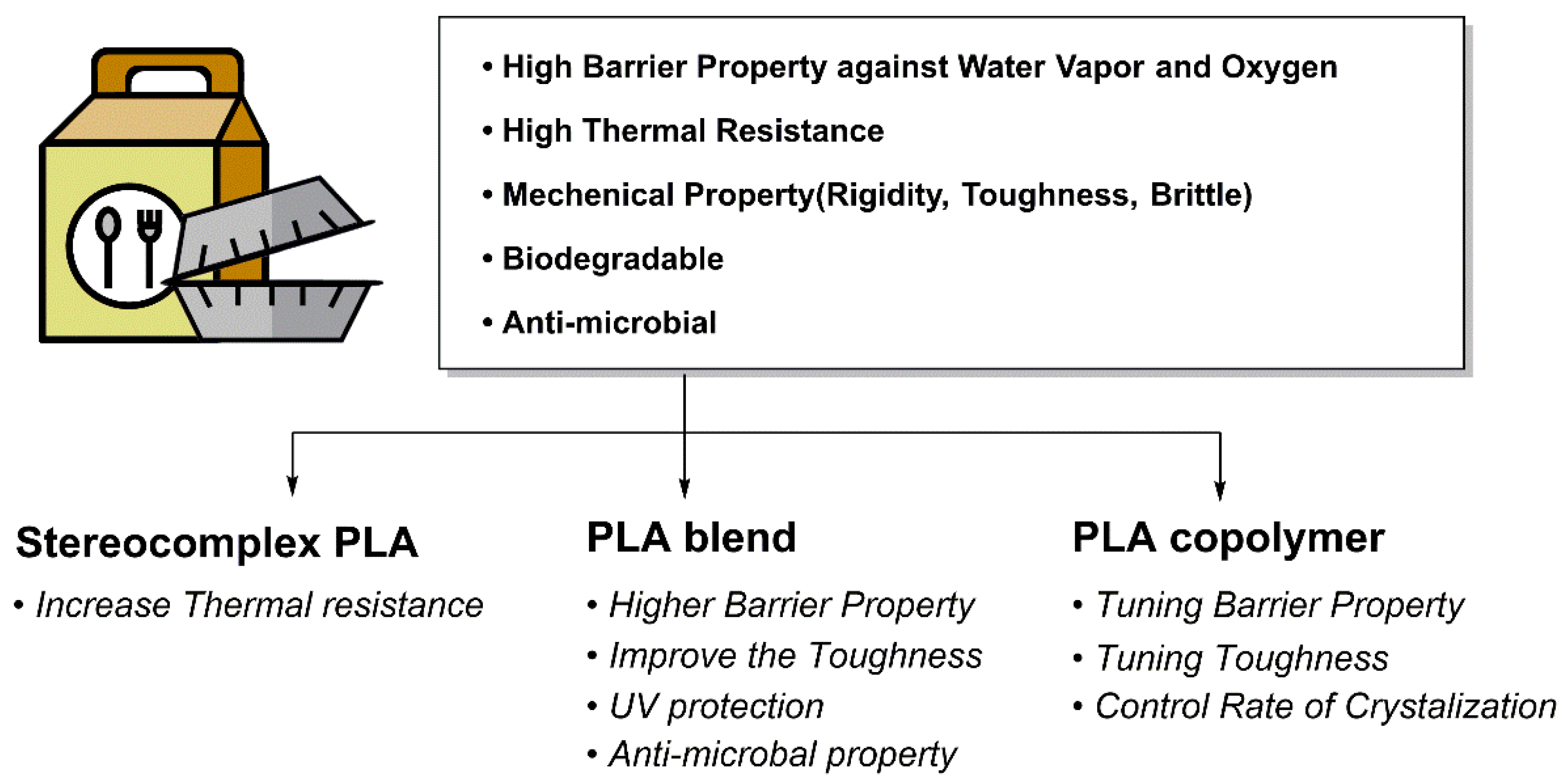

4.1. Food Packaging

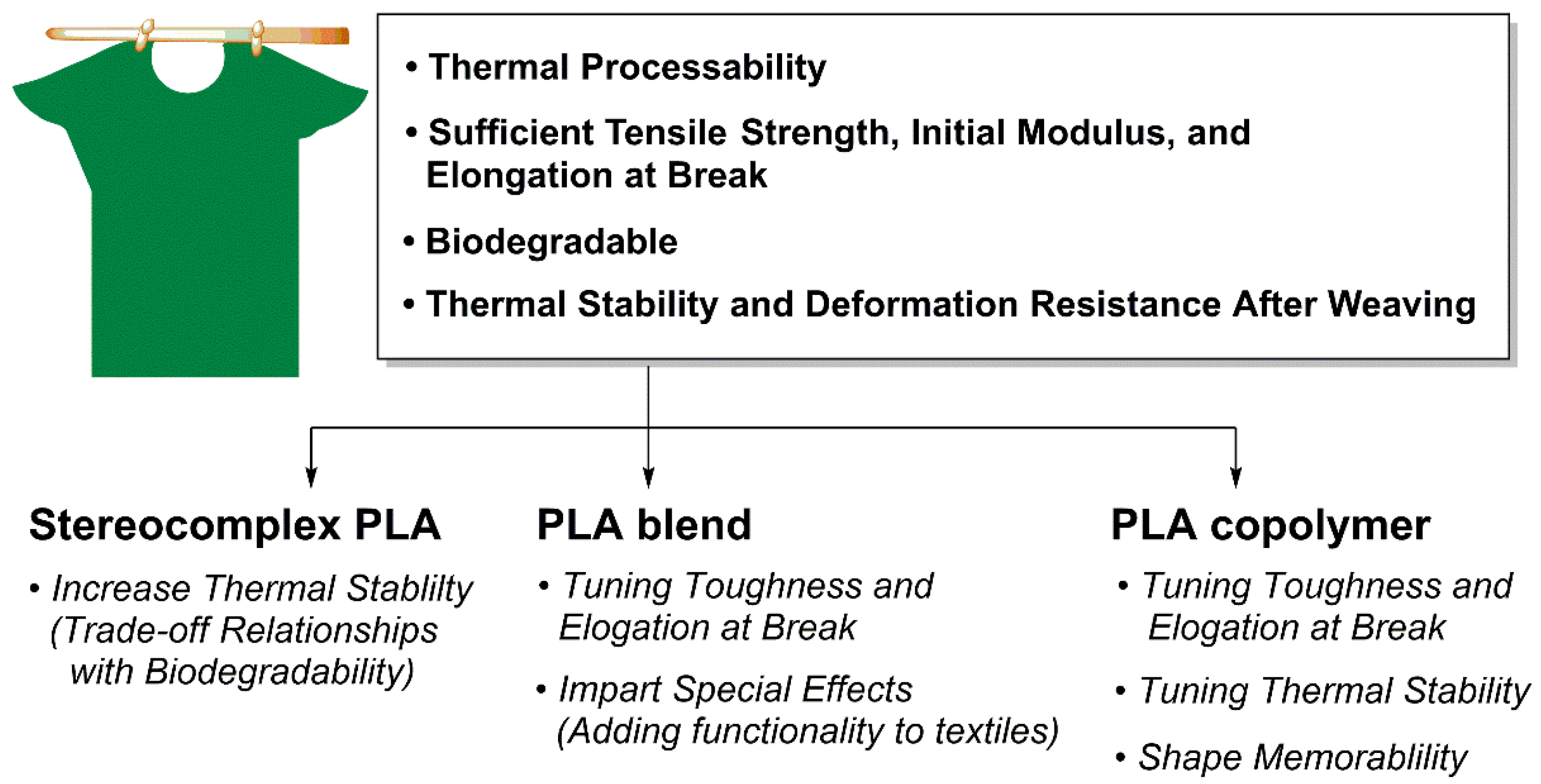

4.2. PLA Fiber

4.3. Agriculture

5. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cverenkárová, K.; Valachovičová, M.; Mackuľak, T.; Žemlička, L.; Bírošová, L. Microplastics in the Food Chain. Life 2021, 11, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, T. Biodegradable and Bio-Based Polymers: Future Prospects of Eco-Friendly Plastics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3210–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidian, M.; Tehrany, E.A.; Imran, M.; Jacquot, M.; Desobry, S. Poly-Lactic Acid: Production, Applications, Nanocomposites, and Release Studies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentano, I.; Bitinis, N.; Fortunati, E.; Mattioli, S.; Rescignano, N.; Verdejo, R.; Lopez-Manchado, M.A.; Kenny, J.M. Multifunctional nanostructured PLA materials for packaging and tissue engineering. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1720–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K.; Kaseem, M.; Yang, H.W.; Deri, F.; Ko, Y.G. Properties and medical applications of polylactic acid: A review. Express Polym. Lett. 2015, 9, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinu, M.; Jackson, C.; Keating, M.Y.; Gardner, K.H. Material Design in Poly(Lactic Acid) Systems: Block Copolymers, Star Homo- and Copolymers, and Stereocomplexes. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 1996, 33, 1497–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthumana, M.; Santhana Gopala Krishnan, P.; Nayak, S.K. Chemical modifications of PLA through copolymerization. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2020, 25, 634–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, E.; Lowy, P.A.; Abdul Rahman, M.; Lykkeberg, A.; Zhou, Y.; Chambenahalli, R.; Garden, J.A. Main group metal polymerisation catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8793–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Tang, C. Controlled Polymerization of Next-Generation Renewable Monomers and Beyond. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1689–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümer, E.H.; Erbil, H.Y. Extrusion-Based 3D Printing Applications of PLA Composites: A Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajioka, M.; Enomoto, K.; Suzuki, K.; Yamaguchi, A. The basic properties of poly(lactic acid) produced by the direct condensation polymerization of lactic acid. J. Environ. Polym. Degrad. 1995, 3, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.I.; Lee, C.W.; Miyamoto, M.; Kimura, Y. Melt polycondensation of L-lactic acid with Sn(II) catalysts activated by various proton acids: A direct manufacturing route to high molecular weight Poly(L-lactic acid). J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.S.; Gil, M.H.; Baptista, C.M.S.G. Improving lactic acid melt polycondensation: The role of co-catalyst. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 128, 2145–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.I.; Kimura, Y. Melt polycondensation of L-lactic acid to poly(L-lactic acid) with Sn(II) catalysts combined with various metal alkoxides. Polym. Int. 2003, 52, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.X.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, E.S.; Yoon, J.S. Synthesis of high-molecular-weight poly(l-lactic acid) through the direct condensation polymerization of l-lactic acid in bulk state. Eur. Polym. J. 2006, 42, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Mechanistic Details of the Titanium-Mediated Polycondensation Reaction of Polyesters: A DFT Study. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinno, K.; Miyamoto, M.; Kimura, Y.; Hirai, Y.; Yoshitome, H. Solid-State Postpolymerization of l-Lactide Promoted by Crystallization of Product Polymer: An Effective Method for Reduction of Remaining Monomer. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 6438–6444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, F.E.; Van Ommen, J.G.; Feijen, J. The mechanism of the ring-opening polymerization of lactide and glycolide. Eur. Polym. J. 1983, 19, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cui, Y.; Xiong, J.; Dai, Z.; Tang, N.; Wu, J. Different mechanisms at different temperatures for the ring-opening polymerization of lactide catalyzed by binuclear magnesium and zinc alkoxides. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 16383–16391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Hung, W.C.; Huang, B.H.; Lin, C.C. Recent Developments in Metal-Catalyzed Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactides and Glycolides: Preparation of Polylactides, Polyglycolide, and Poly(lactide-co-glycolide). In Synthetic Biodegradable Polymers; Rieger, B., Künkel, A., Coates, G.W., Reichardt, R., Dinjus, E., Zevaco, T.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 219–283. [Google Scholar]

- Asano, S.; Aida, T.; Inoue, S. ‘Immortal’ polymerization. Polymerization of epoxide catalysed by an aluminium porphyrin–alcohol system. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1985, 17, 1148–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.P.; Sidera, M.; Fletcher, S.P.; Shaver, M.P. Living and immortal polymerization of seven and six membered lactones to high molecular weights with aluminum salen and salan catalysts. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 74, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platel, R.H.; Hodgson, L.M.; Williams, C.K. Biocompatible Initiators for Lactide Polymerization. Polym. Rev. 2008, 48, 11–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, K.B.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Tolman, W.B. Polymerization of Lactide by Monomeric Sn(II) Alkoxide Complexes. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Poirier, V.; Ghiotto, F.; Bochmann, M.; Cannon, R.D.; Carpentier, J.F.; Sarazin, Y. Kinetic Analysis of the Immortal Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Esters: A Case Study with Tin(II) Catalysts. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 2574–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricheldorf, H.R.; Weidner, S.M.; Scheliga, F. About formation of cycles in Sn(II) octanoate-catalyzed polymerizations of lactides. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2018, 56, 1915–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, M.H.; Eilerts, N.W. Single-site metal alkoxide catalysts for ring-opening polymerizations. Poly(dilactide) synthesis employing {HB(3-Butpz)3}Mg(OEt). Chem. Commun. 1996, 7, 853–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, B.M.; Cheng, M.; Moore, D.R.; Ovitt, T.M.; Lobkovsky, E.B.; Coates, G.W. Polymerization of Lactide with Zinc and Magnesium β-Diiminate Complexes: Stereocontrol and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 3229–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbina, S.; Du, G. Zinc-Catalyzed Highly Isoselective Ring Opening Polymerization of rac-Lactide. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.K.; Breyfogle, L.E.; Choi, S.K.; Nam, W.; Young, V.G.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Tolman, W.B. A Highly Active Zinc Catalyst for the Controlled Polymerization of Lactide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11350–11359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, C.A.; Ireland, B.J.; Hayes, P.G. Activated Zinc Complexes Supported by a Neutral, Phosphinimine-Containing Ligand: Synthesis and Efficacy for the Polymerization of Lactide. Organometallics 2009, 28, 1282–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, I.; Ferrara, V.; Tedesco, C.; Kretschmer, W.; Kempe, R.; Pellecchia, C. Guanidinate Zn(II) Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for Lactide Homo- and Copolymerization under Industrially Relevant Conditions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 4035–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alterio, M.C.; D’Auria, I.; Gaeta, L.; Tedesco, C.; Brenna, S.; Pellecchia, C. Are Well Performing Catalysts for the Ring Opening Polymerization of l-Lactide under Mild Laboratory Conditions Suitable for the Industrial Process? The Case of New Highly Active Zn(II) Catalysts. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 5115–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Ramírez, L.A.; McKeown, P.; Jones, M.D.; Wood, J. Poly(lactic acid) Degradation into Methyl Lactate Catalyzed by a Well-Defined Zn(II) Complex. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Ramírez, L.A.; McKeown, P.; Shah, C.; Abraham, J.; Jones, M.D.; Wood, J. Chemical Degradation of End-of-Life Poly(lactic acid) into Methyl Lactate by a Zn(II) Complex. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 11149–11156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassky, N.; Wisniewski, M.; Pluta, C.; Le Borgne, A. Highly stereoelective polymerization of rac-(D,L)-lactide with a chiral schiff’s base/aluminium alkoxide initiator. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1996, 197, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovitt, T.M.; Coates, G.W. Stereoselective ring-opening polymerization of rac-lactide with a single-site, racemic aluminum alkoxide catalyst: Synthesis of stereoblock poly(lactic acid). J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 4686–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaranas, J.A.; Luke, A.M.; Mandal, M.; Neisen, B.D.; Marell, D.J.; Cramer, C.J.; Tolman, W.B. Sterically Induced Ligand Framework Distortion Effects on Catalytic Cyclic Ester Polymerizations. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 3451–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, W.; Chen, A.; Dong, Z.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Lei, C. Reinvestigation of the ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone with 1,8-diazacyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene organocatalyst in bulk. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 161, 110861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meimoun, J.; Favrelle-Huret, A.; Bria, M.; Merle, N.; Stoclet, G.; De Winter, J.; Mincheva, R.; Raquez, J.M.; Zinck, P. Epimerization and chain scission of polylactides in the presence of an organic base, TBD. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 181, 109188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.P.; Pratt, R.C.; Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Culkin, D.A.; Hagberg, E.C.; Nyce, G.W.; Waymouth, R.M.; Hedrick, J.L. N-Heterocyclic carbenes: Effective organic catalysts for living polymerization. Polymer 2006, 47, 4018–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadota, J.; Pavlović, D.; Desvergne, J.P.; Bibal, B.; Peruch, F.; Deffieux, A. Ring-Opening Polymerization of l-Lactide Catalyzed by an Organocatalytic System Combining Acidic and Basic Sites. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 8874–8879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Pratt, R.C.; Leibfarth, F.; Logan, J.W.; Long, D.A.; Dove, A.P.; Nederberg, F.; Choi, J.; Wade, C.; Waymouth, R.M.; et al. Guanidine and Amidine Organocatalysts for Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Esters. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 8574–8583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.C.; Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Long, D.A.; Lundberg, P.N.P.; Dove, A.P.; Li, H.; Wade, C.G.; Waymouth, R.M.; Hedrick, J.L. Exploration, Optimization, and Application of Supramolecular Thiourea−Amine Catalysts for the Synthesis of Lactide (Co)polymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 7863–7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddu, S.K.; Ur Rehman, N.; Mohanta, T.K.; Majhi, A.; Avula, S.K.; Al-Harrasi, A. A review on DBU-mediated organic transformations. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2022, 15, 765–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.A.; De Crisci, A.G.; Hedrick, J.L.; Waymouth, R.M. Amidine-Mediated Zwitterionic Polymerization of Lactide. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherck, N.J.; Kim, H.C.; Won, Y.Y. Elucidating a Unified Mechanistic Scheme for the DBU-Catalyzed Ring-Opening Polymerization of Lactide to Poly(lactic acid). Macromolecules 2016, 49, 4699–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoponi, G.; Francini, N.; Paradiso, V.; Donno, R.; Gennari, A.; d’Arcy, R.; Capacchione, C.; Athanassiou, A.; Tirelli, N. Versatile Preparation of Branched Polylactides by Low-Temperature, Organocatalytic Ring-Opening Polymerization in N-Methylpyrrolidone and Their Surface Degradation Behavior. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 9482–9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Xu, J.; Tan, C.T.; Tan, C.H. 1,5,7-Triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) catalyzed Michael reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 6875–6878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuma, A.; Horn, H.W.; Swope, W.C.; Pratt, R.C.; Zhang, L.; Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Wade, C.G.; Waymouth, R.M.; Hedrick, J.L.; Rice, J.E. The Reaction Mechanism for the Organocatalytic Ring-Opening Polymerization of l-Lactide Using a Guanidine-Based Catalyst: Hydrogen-Bonded or Covalently Bound? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6749–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moins, S.; Hoyas, S.; Lemaur, V.; Orhan, B.; Delle Chiaie, K.; Lazzaroni, R.; Taton, D.; Dove, A.P.; Coulembier, O. Stereoselective ROP of rac- and meso-Lactides Using Achiral TBD as Catalyst. Catalysts 2020, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.P.; Pratt, R.C.; Lohmeijer, B.G.G.; Waymouth, R.M.; Hedrick, J.L. Thiourea-Based Bifunctional Organocatalysis: Supramolecular Recognition for Living Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13798–13799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazakov, O.I.; Kiesewetter, M.K. Cocatalyst Binding Effects in Organocatalytic Ring-Opening Polymerization of l-Lactide. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 6121–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Waymouth, R.M. Organic Ring-Opening Polymerization Catalysts: Reactivity Control by Balancing Acidity. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 2932–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, M.S.; Wirotius, A.L.; Coulembier, O.; Guichard, G.; Taton, D. A chiral thiourea and a phosphazene for fast and stereoselective organocatalytic ring-opening-polymerization of racemic lactide. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 3777–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, M.S.; Guichard, G.; Taton, D. Structural Effect of Organic Catalytic Pairs Based on Chiral Amino(thio)ureas and Phosphazene Bases for the Isoselective Ring-Opening Polymerization of Racemic Lactide. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 3607–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Wang, M.; Ding, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, B. Organocatalytic ring-opening polymerization of lactide by bis(thiourea) H-bonding donating cocatalysts with binaphthyl-amine framework. Giant 2024, 18, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, C.; Man, L.; Zhang, M.; Jia, Y.G.; Zhu, X.X. Lipase-catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of natural compound-based cyclic monomers. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 9182–9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzasalma, L.; Dove, A.P.; Coulembier, O. Organocatalytic ring-opening polymerization of l-lactide in bulk: A long standing challenge. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 95, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S.; Mabuchi, K.; Toshima, K. Novel ring-opening polymerization of lactide by lipase. Macromol. Symp. 1998, 130, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, M.; Hosoda, N.; Nishiyama, S.; Noguchi, H.; Shoji, A.; Kumar, D.S.; Katsuraya, K.; Ishii, S.; Yoshida, Y. One-pot Enzymatic Synthesis of Poly(L,L-lactide) by Immobilized Lipase Catalyst. Sen’i Gakkaishi 2006, 62, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hans, M.; Keul, H.; Moeller, M. Ring-Opening Polymerization of DD-Lactide Catalyzed by Novozyme 435. Macromol. Biosci. 2009, 9, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa-Fujita, M.; Saito, C.; Takeoka, Y.; Rikukawa, M. Lipase-catalyzed polymerization of L-lactide in ionic liquids. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2008, 19, 1396–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, M.; López-Luna, A.; Shirai, K.; Tecante, A.; Gimeno, M.; Bárzana, E. Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of hyperbranched poly-l-lactide in an ionic liquid. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 36, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S.; Mabuchi, K.; Toshima, K. Lipase-catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of lactide. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 1997, 18, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchiron, S.W.; Pollet, E.; Givry, S.; Avérous, L. Mixed systems to assist enzymatic ring opening polymerization of lactide stereoisomers. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 84627–84635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, S.; Tsukada, K.; Toshima, K. Novel lipase-catalyzed ring-opening copolymerization of lactide and trimethylene carbonate forming poly(ester carbonate)s. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999, 25, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, H.; Lee, C.K.; Mat Nanyan, N.S.; Tay, G.S. Recent Advances in the Enzymatic Synthesis of Polyester. Polymers 2022, 14, 5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.; Cheng, X.; Gao, Y.; Lin, X.; Pan, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, J. Metal-free living cationic ring-opening polymerization of cyclic esters using selenonium salts as Lewis acids. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 2337–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Wang, B.; Ji, H.Y.; Li, Y.S. Insights into the mechanism for ring-opening polymerization of lactide catalyzed by Zn(C6F5)2/organic superbase Lewis pairs. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 7763–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wei, Y.; Li, Z.J.; Pan, L.; Li, Y.S. From Zn(C6F5)2 to ZnEt2-based Lewis Pairs: Significantly Improved Catalytic Activity and Monomer Adaptability for the Ring-opening Polymerization of Lactones. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 5287–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T.; Shibasaki, Y.; Sanda, F. Controlled ring-opening polymerization of cyclic carbonates and lactones by an activated monomer mechanism. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2002, 40, 2190–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazeau-Bureau, S.; Delcroix, D.; Martín-Vaca, B.; Bourissou, D.; Navarro, C.; Magnet, S. Organo-Catalyzed ROP of ϵ-Caprolactone: Methanesulfonic Acid Competes with Trifluoromethanesulfonic Acid. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 3782–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra-Arroni, E.; Ladavière, C.; Amgoune, A.; Bourissou, D. Ring-Opening Polymerization with Zn(C6F5)2-Based Lewis Pairs: Original and Efficient Approach to Cyclic Polyesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13306–13309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, C.; Wu, J. Lewis Pair Catalysts in the Polymerization of Lactide and Related Cyclic Esters. Molecules 2018, 23, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Geng, X.; Zhang, X.; Gnanou, Y.; Feng, X. Alkyl borane-mediated metal-free ring-opening (co)polymerizations of oxygenated monomers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 136, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricheldorf, H.R.; Weidner, S.M. High molar mass cyclic poly(l-lactide) obtained by means of neat tin(ii) 2-ethylhexanoate. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 5249–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricheldorf, H.R.; Weidner, S.M. Syntheses of polylactides by means of tin catalysts. Polym. Chem. 2022, 13, 1618–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, S.M.; Kricheldorf, H.R. SnOct2-catalyzed ROPs of l-lactide initiated by acidic OH- compounds: Switching from ROP to polycondensation and cyclization. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricheldorf, H.R.; Weidner, S.M.; Scheliga, F. SnOct2-Catalyzed and Alcohol-Initiated ROPS of l-Lactide—Control of the Molecular Weight and the Role of Cyclization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2022, 223, 2100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, S.M.; Meyer, A.; Falkenhagen, J.; Kricheldorf, H.R. Polycondensations and cyclization of poly(l-lactide) ethyl esters in the solid state. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschan, M.J.L.; Gauvin, R.M.; Thomas, C.M. Controlling polymer stereochemistry in ring-opening polymerization: A decade of advances shaping the future of biodegradable polyesters. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 13587–13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huo, Z.; Jang, E.; Tong, R. Recent advances in enantioselective ring-opening polymerization and copolymerization. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, A.; Gaston, A.J.; Greindl, Z.; Garden, J.A. Electron rich (salen)AlCl catalysts for lactide polymerisation: Investigation of the influence of regioisomers on the rate and initiation efficiency. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 138, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K.; Furuhashi, Y.; Sogo, K.; Miura, S.; Kimura, Y. Stereoblock Poly(lactic acid): Synthesis via Solid-State Polycondensation of a Stereocomplexed Mixture of Poly(L-lactic acid) and Poly(D-lactic acid). Macromol. Biosci. 2005, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, K.; Hirata, M.; Kimura, Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Stereoblock Poly(lactic acid)s with Nonequivalent D/L Sequence Ratios. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 3049–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.A.; Kim, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Deep, A. Hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid (PLA) and its composites. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liao, X.; He, G.; Li, S.; Guo, F.; Li, G. Green Method to Widen the Foaming Processing Window of PLA by Introducing Stereocomplex Crystallites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 21466–21475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikada, Y.; Jamshidi, K.; Tsuji, H.; Hyon, S.H. Stereocomplex formation between enantiomeric poly(lactides). Macromolecules 1987, 20, 904–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Ikada, Y. Stereocomplex formation between enantiomeric poly(lactic acid)s. XI. Mechanical properties and morphology of solution-cast films. Polymer 1999, 40, 6699–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Tezuka, Y. Stereocomplex Formation between Enantiomeric Poly(lactic acid)s. 12. Spherulite Growth of Low-Molecular-Weight Poly(lactic acid)s from the Melt. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. Benign Fabrication of Fully Stereocomplex Polylactide with High Molecular Weights via a Thermally Induced Technique. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 7979–7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Hong, C.K. Relationship between the Stereocomplex Crystallization Behavior and Mechanical Properties of PLLA/PDLA Blends. Polymers 2021, 13, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isono, T.; Kondo, Y.; Otsuka, I.; Nishiyama, Y.; Borsali, R.; Kakuchi, T.; Satoh, T. Synthesis and Stereocomplex Formation of Star-Shaped Stereoblock Polylactides Consisting of Poly(l-lactide) and Poly(d-lactide) Arms. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 8509–8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wu, W.; Wu, W.; Gao, Q. Competitive Mechanism of Stereocomplexes and Homocrystals in High-Performance Symmetric and Asymmetric Poly(lactic acid) Enantiomers: Qualitative Methods. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 41412–41425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Bian, X.; Li, G.; Chen, X. Thermal Properties and Structural Evolution of Poly(l-lactide)/Poly(d-lactide) Blends. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 10163–10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Yoshie, N. Self-Assembly of Stereocomplex-Type Poly(lactic acid). Polym. J. 2006, 38, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.F.; Bao, R.Y.; Cao, Z.Q.; Yang, W.; Xie, B.H.; Yang, M.B. Stereocomplex Crystallite Network in Asymmetric PLLA/PDLA Blends: Formation, Structure, and Confining Effect on the Crystallization Rate of Homocrystallites. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michell, R.M.; Ladelta, V.; Da Silva, E.; Müller, A.J.; Hadjichristidis, N. Poly(lactic acid) stereocomplexes based molecular architectures: Synthesis and crystallization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 146, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, S.; Dubois, C.; Lafleur, P.G. Homocrystal and stereocomplex formation behavior of polylactides with different branched structures. Polymer 2015, 67, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Kopitzky, R.; Tolga, S.; Kabasci, S. Polylactide (PLA) and Its Blends with Poly(butylene succinate) (PBS): A Brief Review. Polymers 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokohara, T.; Yamaguchi, M. Structure and properties for biomass-based polyester blends of PLA and PBS. Eur. Polym. J. 2008, 44, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Itry, R.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A. Reactive extrusion of PLA, PBAT with a multi-functional epoxide: Physico-chemical and rheological properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 58, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.K.; Zaccone, M.; De Brauwer, L.; Nair, R.; Monti, M.; Martinez-Nogues, V.; Frache, A.; Oksman, K. Improvement of Poly(lactic acid)-Poly(hydroxy butyrate) Blend Properties for Use in Food Packaging: Processing, Structure Relationships. Polymers 2022, 14, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Tena, A.; Otaegi, I.; Irusta, L.; Sebastián, V.; Guerrica-Echevarria, G.; Müller, A.J.; Aranburu, N. High-Impact PLA in Compatibilized PLA/PCL Blends: Optimization of Blend Composition and Type and Content of Compatibilizer. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2023, 308, 2300213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broz, M.E.; VanderHart, D.L.; Washburn, N.R. Structure and mechanical properties of poly(d,l-lactic acid)/poly(ε-caprolactone) blends. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4181–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rodríguez, N.; López-Arraiza, A.; Meaurio, E.; Sarasua, J.R. Crystallization, morphology, and mechanical behavior of polylactide/poly(ε-caprolactone) blends. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2006, 46, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquijo, J.; Guerrica-Echevarría, G.; Eguiazábal, J.I. Melt processed PLA/PCL blends: Effect of processing method on phase structure, morphology, and mechanical properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 42641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhai, T.; Turng, L.S.; Dan, Y. Morphological, Mechanical, and Crystallization Behavior of Polylactide/Polycaprolactone Blends Compatibilized by l-Lactide/Caprolactone Copolymer. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 9505–9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Iida, K.; Okamoto, K.; Hayashi, H.; Hirano, K. Reactive compatibilization of biodegradable poly(lactic acid)/poly(ε-caprolactone) blends with reactive processing agents. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2008, 48, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lin, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Lin, B. Selective Localization of Nanofillers: Effect on Morphology and Crystallization of PLA/PCL Blends. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2011, 212, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damonte, G.; Barsanti, B.; Pellis, A.; Guebitz, G.M.; Monticelli, O. On the effective application of star-shaped polycaprolactones with different end functionalities to improve the properties of polylactic acid blend films. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 176, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J. Properties of Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/Nanoparticle Ternary Composites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 7594–7602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, R.; Lee, W.; Kwak, S.Y. A facile strategy for enhancing tensile toughness of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) by blending of a cellulose bio-toughener bearing a highly branched polycaprolactone. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 175, 111376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiong, C.; Deng, X. Miscibility, crystallization and morphology of poly(β-hydroxybutyrate)/poly(d,l-lactide) blends. Polymer 1996, 37, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Thomas, N.L. Blending polylactic acid with polyhydroxybutyrate: The effect on thermal, mechanical, and biodegradation properties. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2011, 30, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; Samper, M.D.; López, J.; Jiménez, A. Combined Effect of Poly(hydroxybutyrate) and Plasticizers on Polylactic acid Properties for Film Intended for Food Packaging. J. Polym. Environ. 2014, 22, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Sato, H.; Zhang, J.; Noda, I.; Ozaki, Y. Crystallization behavior of poly(l-lactic acid) affected by the addition of a small amount of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate). Polymer 2008, 49, 4204–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blümm, E.; Owen, A.J. Miscibility, crystallization and melting of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)/ poly(l-lactide) blends. Polymer 1995, 36, 4077–4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Luo, R.; Xu, K.; Chen, G.Q. Thermal and crystallinity property studies of poly (L-lactic acid) blended with oligomers of 3-hydroxybutyrate or dendrimers of hydroxyalkanoic acids. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 111, 1720–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, M.A.; Flynn, A.; Chiou, B.S.; Imam, S.; Orts, W.; Chiellini, E. Thermal, mechanical and morphological characterization of plasticized PLA–PHB blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; Fortunati, E.; Dominici, F.; López, J.; Kenny, J.M. Bionanocomposite films based on plasticized PLA–PHB/cellulose nanocrystal blends. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 121, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Edeleva, M.; Wang, G.; Cardon, L.; D’hooge, D.R. Reactive blending of deliberately degraded polyhydroxy-butyrate with poly(lactic acid) and maleic anhydride to enhance biopolymer mechanical property variations. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 230, 113890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Itry, R.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A. Rheological, morphological, and interfacial properties of compatibilized PLA/PBAT blends. Rheol. Acta 2014, 53, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.; Dorigato, A.; Morreale, M.; Pegoretti, A. Evaluation of the Physical and Shape Memory Properties of Fully Biodegradable Poly(lactic acid) (PLA)/Poly(butylene adipate terephthalate) (PBAT) Blends. Polymers 2023, 15, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Lu, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, G.; Ji, J. PLA-PBAT-PLA tri-block copolymers: Effective compatibilizers for promotion of the mechanical and rheological properties of PLA/PBAT blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 147, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Feng, W.; Lu, B.; Wang, P.; Wang, G.; Ji, J. PLA-PEG-PLA tri-block copolymers: Effective compatibilizers for promotion of the interfacial structure and mechanical properties of PLA/PBAT blends. Polymer 2018, 146, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zha, C.; Qiao, Z.; Fu, Q.; Bai, H. Achieving high impact toughness and heat resistance in biodegradable PLA/PBAT blends via interfacial construction of stereocomplex crystallites. Polymer 2025, 329, 128487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Weng, Y.; Bian, X.; Chen, X. Degradation Behaviors of Polylactic Acid, Polyglycolic Acid, and Their Copolymer Films in Simulated Marine Environments. Polymers 2024, 16, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Dana, H.; Ebrahimi, F. Synthesis, properties, and applications of polylactic acid-based polymers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, S.; Laudadio, E.; Minnelli, C.; Stipa, P. Tailoring the Barrier Properties of PLA: A State-of-the-Art Review for Food Packaging Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Auras, R.; Kirkensgaard, J.J.K.; Uysal-Unalan, I. Modulating Barrier Properties of Stereocomplex Polylactide: The Polymorphism Mechanism and Its Relationship with Rigid Amorphous Fraction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 49678–49688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrosanto, A.; Scarfato, P.; Di Maio, L.; Nobile, M.R.; Incarnato, L. Evaluation of the Suitability of Poly(Lactide)/Poly(Butylene-Adipate-co-Terephthalate) Blown Films for Chilled and Frozen Food Packaging Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, O.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, Y.H. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(l-lactide)−Poly(ε-caprolactone) Multiblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 5585–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, A.; Hsu, Y.I.; Uyama, H. Biodegradable poly(lactic acid) and polycaprolactone alternating multiblock copolymers with controllable mechanical properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 218, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangroniz, A.; Sangroniz, L.; Hamzehlou, S.; del Río, J.; Santamaria, A.; Sarasua, J.R.; Iriarte, M.; Leiza, J.R.; Etxeberria, A. Lactide-caprolactone copolymers with tuneable barrier properties for packaging applications. Polymer 2020, 202, 122681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Synthesis of Poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) Copolymer: Structure, Toughness, and Elasticity. Polymers 2021, 13, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhao, M.; Xu, F.; Yang, B.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Teng, L.; Sun, F.; Li, Y. Synthesis and Biological Application of Polylactic Acid. Molecules 2020, 25, 5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Hsu, Y.I.; Uyama, H. Superior sequence-controlled poly(L-lactide)-based bioplastic with tunable seawater biodegradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 474, 134819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Hsu, Y.I.; Uyama, H. Design of novel poly(L-lactide)-based shape memory multiblock copolymers for biodegradable esophageal stent application. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 36, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, B.; Sun, T.; Zhang, J.; Yun, X.; Dong, T. Towards ductile and high barrier poly(L-lactic acid) ultra-thin packaging film by regulating chain structures for efficient preservation of cherry tomatoes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Tiwari, M. Structure-Processing-Property Relationship of Poly(Glycolic Acid) for Drug Delivery Systems 1:Synthesis and Catalysis. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2010, 2010, 652719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakafuku, C.; Yoshimura, H. Melting parameters of poly(glycolic acid). Polymer 2004, 45, 3583–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yan, G.; Gao, J.; Guo, H.; Hou, Q. Advances in Valorization of Biomass-Derived Glycolic Acid Toward Polyglycolic Acid Production. Catalysts 2024, 14, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.; Wemyss, A.M.; Haddleton, D.M.; Tan, B.; Sun, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wan, C. Synthesis of Poly(Lactic Acid-co-Glycolic Acid) Copolymers with High Glycolide Ratio by Ring-Opening Polymerisation. Polymers 2021, 13, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhavan Nampoothiri, K.; Nair, N.R.; John, R.P. An overview of the recent developments in polylactide (PLA) research. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8493–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—A comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Khan, S.M.; Shafiq, M.; Abbas, N. A review on PLA-based biodegradable materials for biomedical applications. Giant 2024, 18, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.J.; Chen, S.C.; Yang, K.K.; Wang, Y.Z. Biodegradable polylactide based materials with improved crystallinity, mechanical properties and rheological behaviour by introducing a long-chain branched copolymer. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 42162–42173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wu, Y.; Bai, Z.; Guo, J.; Chen, X. Effect of molecular weight of polyethylene glycol on crystallization behaviors, thermal properties and tensile performance of polylactic acid stereocomplexes. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42120–42127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia Valderrama, M.A.; van Putten, R.J.; Gruter, G.J.M. PLGA Barrier Materials from CO2. The influence of Lactide Co-monomer on Glycolic Acid Polyesters. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 2706–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashkov, I.; Manolova, N.; Li, S.M.; Espartero, J.L.; Vert, M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Hydrolytic Degradation of PLA/PEO/PLA Triblock Copolymers with Short Poly(l-lactic acid) Chains. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.J.; Xiangzhou, L.; Shilin, Y. Preparation, characterization, and properties of polylactide (PLA)–poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) copolymers: A potential drug carrier. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1990, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Zhu, K.J.; Pitt, C.G. Poly-DL-lactic acid: Polyethylene glycol block copolymers. The influence of polyethylene glycol on the degradation of poly-DL-lactic acid. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 1994, 5, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilding, D.K.; Reed, A.M. Biodegradable polymers for use in surgery—Polyglycolic/poly(actic acid) homo- and copolymers: 1. Polymer 1979, 20, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.M.; Gilding, D.K. Biodegradable polymers for use in surgery—Poly(glycolic)/poly(Iactic acid) homo and copolymers: 2. In vitro degradation. Polymer 1981, 22, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, D.J.; Kaplan, D.L. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid-controlled-release systems: Experimental and modeling insights. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2013, 30, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J.; Skidmore, S.; Park, H.; Park, K.; Choi, S.; Wang, Y. A protocol for assay of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) in clinical products. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 495, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Swisher, J.H.; Meyer, T.Y.; Coates, G.W. Chirality-Directed Regioselectivity: An Approach for the Synthesis of Alternating Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4119–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, B.; Bostan, L.; Herrmann, A.S.; Boskamp, L.; Koschek, K. Properties of Stereocomplex PLA for Melt Spinning. Polymers 2023, 15, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanek, I.; Cvek, M.; Rogacz, D.; Żarski, A.; Lewicka, K.; Sedlarik, V.; Rychter, P. Degradation of Polylactic Acid/Polypropylene Carbonate Films in Soil and Phosphate Buffer and Their Potential Usefulness in Agriculture and Agrochemistry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshma, C.S.; Remya, S.; Bindu, J. A review of exploring the synthesis, properties, and diverse applications of poly lactic acid with a focus on food packaging application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Katiyar, V. Cellulose Functionalized High Molecular Weight Stereocomplex Polylactic Acid Biocomposite Films with Improved Gas Barrier, Thermomechanical Properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 6835–6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Mulchandani, N.; Shah, M.; Kumar, S.; Katiyar, V. Functionalized chitosan mediated stereocomplexation of poly(lactic acid): Influence on crystallization, oxygen permeability, wettability and biocompatibility behavior. Polymer 2018, 142, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Auras, R.; Uysal-Unalan, I. Role of stereocomplex in advancing mass transport and thermomechanical properties of polylactide. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 3416–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supmak, W.; Buchatip, S.; Opaprakasit, M.; Petchsuk, A.; Opaprakasit, P. Star polylactide and its stereocomplex blends with enhanced heat stability triggered by microwave heating for degradable packaging. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahangiri, F.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Sustainable biodegradable coatings for food packaging: Challenges and opportunities. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 4934–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olonisakin, K.; Mohanty, A.K.; Thimmanagari, M.; Misra, M. Recent advances in biodegradable polymer blends and their biocomposites: A comprehensive review. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 11656–11704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, O.; Avérous, L. Poly(lactic acid): Plasticization and properties of biodegradable multiphase systems. Polymer 2001, 42, 6209–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A. Poly(lactic) acid (PLA) and starch bilayer films, containing cinnamaldehyde, obtained by compression moulding. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 95, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; López, J.; Hernández, A.; Rayón, E. Ternary PLA–PHB–Limonene blends intended for biodegradable food packaging applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 50, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.P.; Samper, M.D.; Aldas, M.; López, J. On the Use of PLA-PHB Blends for Sustainable Food Packaging Applications. Materials 2017, 10, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-García, E.; Vargas, M.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Biodegradation of PLA-PHBV Blend Films as Affected by the Incorporation of Different Phenolic Acids. Foods 2022, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.W. Preparation of antibacterial poly(lactide)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite films incorporated with grapefruit seed extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Perera, K.Y.; Pradhan, D.; Duffy, B.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Active Packaging Film Based on Poly Lactide-Poly (Butylene Adipate-Co-Terephthalate) Blends Incorporated with Tannic Acid and Gallic Acid for the Prolonged Shelf Life of Cherry Tomato. Coatings 2022, 12, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, L.L.R.L.; Silva, L.G.L.; Abreu, I.R.; Braz, C.J.F.; Rodrigues, S.C.S.; Moreira-Araújo, R.S.D.R.; Folkersma, R.; de Carvalho, L.H.; Barbosa, R.; Alves, T.S. Biodegradable PBAT/PLA blend films incorporated with turmeric and cinnamomum powder: A potential alternative for active food packaging. Food Chem. 2024, 439, 138146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Huang, Z.; Yang, F.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, C. The effect of polylactic acid-based blend films modified with various biodegradable polymers on the preservation of strawberries. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 45, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Inoue, Y.; Miyoshi, M. Mechanical properties, morphology, and crystallization behavior of blends of poly(l-lactide) with poly(butylene succinate-co-l-lactate) and poly(butylene succinate). Polymer 2006, 47, 3557–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supthanyakul, R.; Kaabbuathong, N.; Chirachanchai, S. Random poly(butylene succinate-co-lactic acid) as a multi-functional additive for miscibility, toughness, and clarity of PLA/PBS blends. Polymer 2016, 105, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ju, Z.; Tam, P.Y.; Hua, T.; Younas, M.W.; Kamrul, H.; Hu, H. Poly(lactic acid) fibers, yarns and fabrics: Manufacturing, properties and applications. Text. Res. J. 2020, 91, 1641–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shi, Y.; Wang, P.; Yang, Q.; Gobius du Sart, G.; Zhou, Y.; Joziasse, C.A.P.; Wang, R.; Chen, P. Facile and efficient formation of stereocomplex polylactide fibers drawn at low temperatures. Polymer 2022, 246, 124743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddeo, M.; Sorrentino, A.; Pappalardo, D. Thermo-Rheological and Shape Memory Properties of Block and Random Copolymers of Lactide and ε-Caprolactone. Polymers 2021, 13, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriyai, M.; Tasati, J.; Molloy, R.; Meepowpan, P.; Somsunan, R.; Worajittiphon, P.; Daranarong, D.; Meerak, J.; Punyodom, W. Development of an Antimicrobial-Coated Absorbable Monofilament Suture from a Medical-Grade Poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) Copolymer. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 28788–28803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Mano, J.F. Multiple melting behaviour of poly(l-lactide-co-glycolide) investigated by DSC. Polym. Test. 2009, 28, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrasi, G.; Meduri, A.; Rizzarelli, P.; Carroccio, S.; Curcuruto, G.; Pellecchia, C.; Pappalardo, D. Preparation of poly(glycolide-co-lactide)s through a green process: Analysis of structural, thermal, and barrier properties. React. Funct. Polym. 2016, 109, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuoco, T.; Mathisen, T.; Finne-Wistrand, A. Poly(l-lactide) and Poly(l-lactide-co-trimethylene carbonate) Melt-Spun Fibers: Structure–Processing–Properties Relationship. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1346–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, R.; Li, X.L.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, X.R.; Shi, L.Y.; Yang, K.K.; Wang, Y.Z. Fabrication of high-strength and tough PLA/PBAT composites via in-situ copolymer formation using an adaptable epoxy extender. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 140530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cao, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Bao, J. Extraordinary toughness and heat resistance enhancement of biodegradable PLA/PBS blends through the formation of a small amount of interface-localized stereocomplex crystallites during melt blending. Polymer 2022, 262, 125454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Durable Polylactic Acid (PLA)-Based Sustainable Engineered Blends and Biocomposites: Recent Developments, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACS Eng. Au 2021, 1, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xie, D.; Yang, C. Effects of a PLA/PBAT biodegradable film mulch as a replacement of polyethylene film and their residues on crop and soil environment. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, Z.; Tchuenbou-Magaia, F.; Kowalczuk, M.; Adamus, G.; Manning, G.; Parati, M.; Radecka, I.; Khan, H. Polymers Use as Mulch Films in Agriculture—A Review of History, Problems and Current Trends. Polymers 2022, 14, 5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Zych, A.; Athanassiou, A. Biodegradable and Biobased Mulch Films: Highly Stretchable PLA Composites with Different Industrial Vegetable Waste. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 46920–46931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Pal, A.K.; Woo, E.M.; Katiyar, V. Effects of Amphiphilic Chitosan on Stereocomplexation and Properties of Poly(lactic acid) Nano-biocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Blends of poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and stereocomplex polylactide with improved rheological and mechanical properties. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 10482–10490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, D.; Gong, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Hong, H.; Yao, J. Lignin-derivable block copolymer micelle for effectively reinforcing and toughening polylactic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrini, F.; Gomes, R.C.; Moraes, A.S.; Antunes, B.S.L.; Motta, A.C.; Dávila, J.L.; Hausen, M.A.; Komatsu, D.; Duek, E.A.R. Poly(L-co-D,L-lactic acid-co-trimethylene carbonate) for extrusion-based 3D printing: Comprehensive characterization and cytocompatibility assessment. Polymer 2024, 290, 126585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnoor, B.; Elhendawy, A.; Joseph, S.; Putman, M.; Chacón-Cerdas, R.; Flores-Mora, D.; Bravo-Moraga, F.; Gonzalez-Nilo, F.; Salvador-Morales, C. Engineering Atrazine Loaded Poly (lactic-co-glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles to Ameliorate Environmental Challenges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 7889–7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhvi, M.S.; Zinjarde, S.S.; Gokhale, D.V. Polylactic acid: Synthesis and biomedical applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Revagade, N.; Hilborn, J. Poly(lactic acid) fiber: An overview. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.M.; Cutright, D.E.; Miller, R.A.; Battistone, G.C.; Hunsuck, E.E. Resorption rate, route of elimination, and ultrastructure of the implant site of polylactic acid in the abdominal wall of the rat. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1973, 7, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postema, A.R.; Luiten, A.H.; Oostra, H.; Pennings, A.J. High-strength poly(L-lactide) fibers by a dry-spinning/hot-drawing process. II. Influence of the extrusion speed and winding speed on the dry-spinning process. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1990, 39, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fambri, L.; Pegoretti, A.; Fenner, R.; Incardona, S.D.; Migliaresi, C. Biodegradable fibres of poly(l-lactic acid) produced by melt spinning. Polymer 1997, 38, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.R.; Bowlin, G.L.; Mansfield, K.; Layman, J.; Simpson, D.G.; Sanders, E.H.; Wnek, G.E. Release of tetracycline hydrochloride from electrospun poly(ethylene-co-vinylacetate), poly(lactic acid), and a blend. J. Control. Release 2002, 81, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.A.M.; Elarabi, S.E.; Wei, Y.; Yu, M. Biodegradable poly (lactic acid)/poly (butylene succinate) fibers with high elongation for health care products. Text. Res. J. 2017, 88, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangnorawich, B.; Magmee, A.; Roungpaisan, N.; Toommee, S.; Parcharoen, Y.; Pechyen, C. Effect of Polybutylene Succinate Additive in Polylactic Acid Blend Fibers via a Melt-Blown Process. Molecules 2023, 28, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, B.; Wei, W.; Gu, Q.; Chen, P. Properties and structure of polylactide/poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PLA/PHBV) blend fibers. Polymer 2015, 68, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumbia, A.S.; Vezin, H.; Ferreira, M.; Campagne, C.; Devaux, E. Studies of polylactide/zinc oxide nanocomposites: Influence of surface treatment on zinc oxide antibacterial activities in textile nanocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annandarajah, C.; Norris, E.J.; Funk, R.; Xiang, C.; Grewell, D.; Coats, J.R.; Mishek, D.; Maloy, B. Biobased plastics with insect-repellent functionality. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2019, 59, E460–E467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintim, H.Y.; Flury, M. Is Biodegradable Plastic Mulch the Solution to Agriculture’s Plastic Problem? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1068–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst System | Typical Conditions | Achievable Mw (kg/mol) | Polydispersity (Đ) | Stereocontrol | Toxicity | Scalability & Maturity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn(Oct)2 | 130–180 °C | 100–320 | Broad | Limited | Residual Sn (medical restriction) | Industrial benchmark | [78,79,80,81,82] |

| Zn-based complexes | 20–160 °C | 50–130 | 1.05–1.70 | Good | Low toxicity | Lab-pilot | [29,30,31,32,33] |

| Al-based complexes | 70–120 °C | 10–60 | 1.10–1.30 | Excellent | Low toxicity | Lab–scale | [37,38,39,83,84,85] |

| Organocatalysts (DBU, TBD, Thiourea) | −25 °C | 10–100 | 1.05–1.25 | Moderate | Metal-free | Lab-scale | [43,44,45,47,48,49,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Enzyme catalysts (CAL-B, BCL, PPL) | 50–130 °C | <70 | Broad | Moderate | Metal-free/Green | Limited (low yield, long reaction time) | [63,66,67,69] |

| Lewis pair/FLP | 40–110 °C | 30–40 | 1.10–1.40 | Limited | Low toxicity | Lab-scale (emerging) | [71,72,75,76,77] |

| Direct polycondensation | 130–180 °C | 20–50 | Broad | Poor-Moderate | Metal catalyst residue | Limited | [12,13,14,15,16,86,87] |

| Modification Strategy | Toughness | Heat Resistance | Barrier Properties | Biodegradability | Processability | Key Trade-Offs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLA | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Brittleness | [94,130,131,132] |

| Stereocomplex PLA (scPLA) | Low–moderate | Very high | High | Low | Poor | Processing | [90,91,92,96,97,98,133] |

| PLA/PCL blends | High | Low | Low | High | Good | Strength | [110,113,115] |

| PLA/PHB blends | Low | Moderate | High | High | Moderate | Brittleness | [105,116,117] |

| PLA/PBAT blends | Very high | Low | Moderate | High | Good | Strength | [125,126,134] |

| PLA/PCL copolymers | High | Tunable | Low-Moderate | High | Good | Strength | [106,135,136,137,138] |

| PLA/PEG copolymers | High | Low | Moderate | High | Good | Moisture sensitivity | [139,140,141,142] |

| PLA/PGA copolymers | Low | High | Very high | Tunable | Poor | Brittleness | [143,144,145,146] |

| Material System | Environment | Conditions | Degradation Metric | Time Scale | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLA | Compost | 58 °C | 34.4% disintegration (% mass loss, DIN EN ISO 20200) | 3 months | [161] |

| Neat PLA | Soil | 22 ± 2 °C | No Mn change (≤3 months) Mn ≈ 50% (24 months) | 24 months | [162] |

| Neat PLA | Marine | 25 °C | No major macroscopic change (≤4 months) slow Mn decrease thereafter | 10 months | [130] |

| scPLA | Compost | 58 °C | 28.6% disintegration (% mass loss, DIN EN ISO 20200) | 3 months | [161] |

| PLA/PCL | Marine | 30 °C | 11% Mn remaining (ASTM D6691–based seawater) | 6 months | [136] |

| PLA/PEG | Marine | 20 °C | 72.63% biodegradation, 71.5% mass loss (BOD, OECD 306) | 28 days | [140] |

| PLA/PGA | Marine | 25 °C | Mn decreases faster than neat PLA (rate increases with GA content) | 4–10 months | [130] |

| Application | Key Requirements | PLA Design | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food packaging | Gas and Water barrier properties, Thermal Resistance, Toughness, Biodegradable | ScPLA, Blend (TPS, PHB, PBAT) Copolymer (PCL, PEG, PGA, PBS) | [133,137,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180] |

| Fiber and textile | Processability, Toughness, Biodegradable, Thermal Stability | ScPLA, Blend (cotton, cellulose-based fibers) Copolymer (PCL, PGA) | [161,181,182,183,184,185,186,187] |

| Agriculture | Thermal Resistance, Toughness, Controlled degradation | ScPLA, Blend (PBAT, PBS, PCL, PHA, PBS) Copolymer (PCL, PGA, succinate, trimethylene carbonate) | [12,89,113,115,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wi, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.-H. PLA-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Synthesis to the Application. Polymers 2026, 18, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010121

Wi J, Choi J, Lee S-H. PLA-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Synthesis to the Application. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleWi, Junui, Jimin Choi, and Sang-Ho Lee. 2026. "PLA-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Synthesis to the Application" Polymers 18, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010121

APA StyleWi, J., Choi, J., & Lee, S.-H. (2026). PLA-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Synthesis to the Application. Polymers, 18(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010121