Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Bio-Adsorbents for the Biosorption of Chromium Ions from Aqueous Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Synthetic Wastewater Samples

2.3. Preparation of Adsorbents

2.4. Characterization

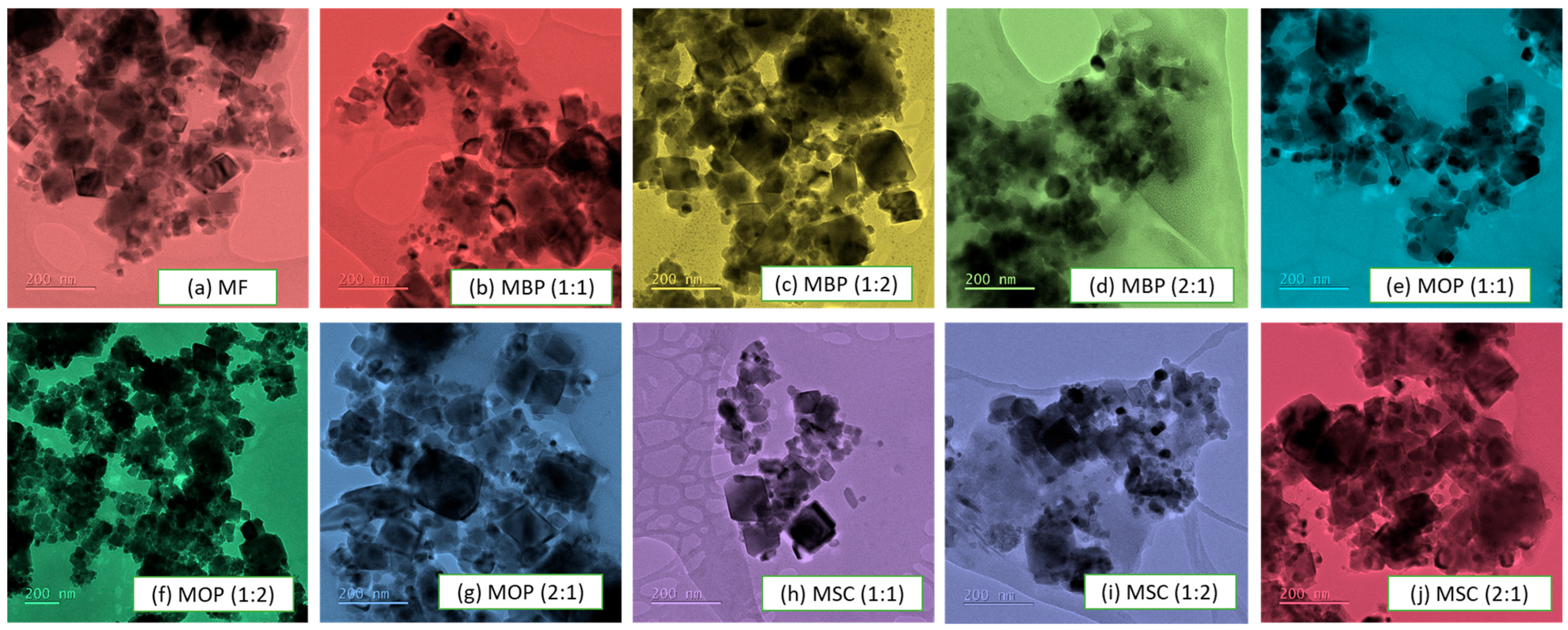

2.4.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

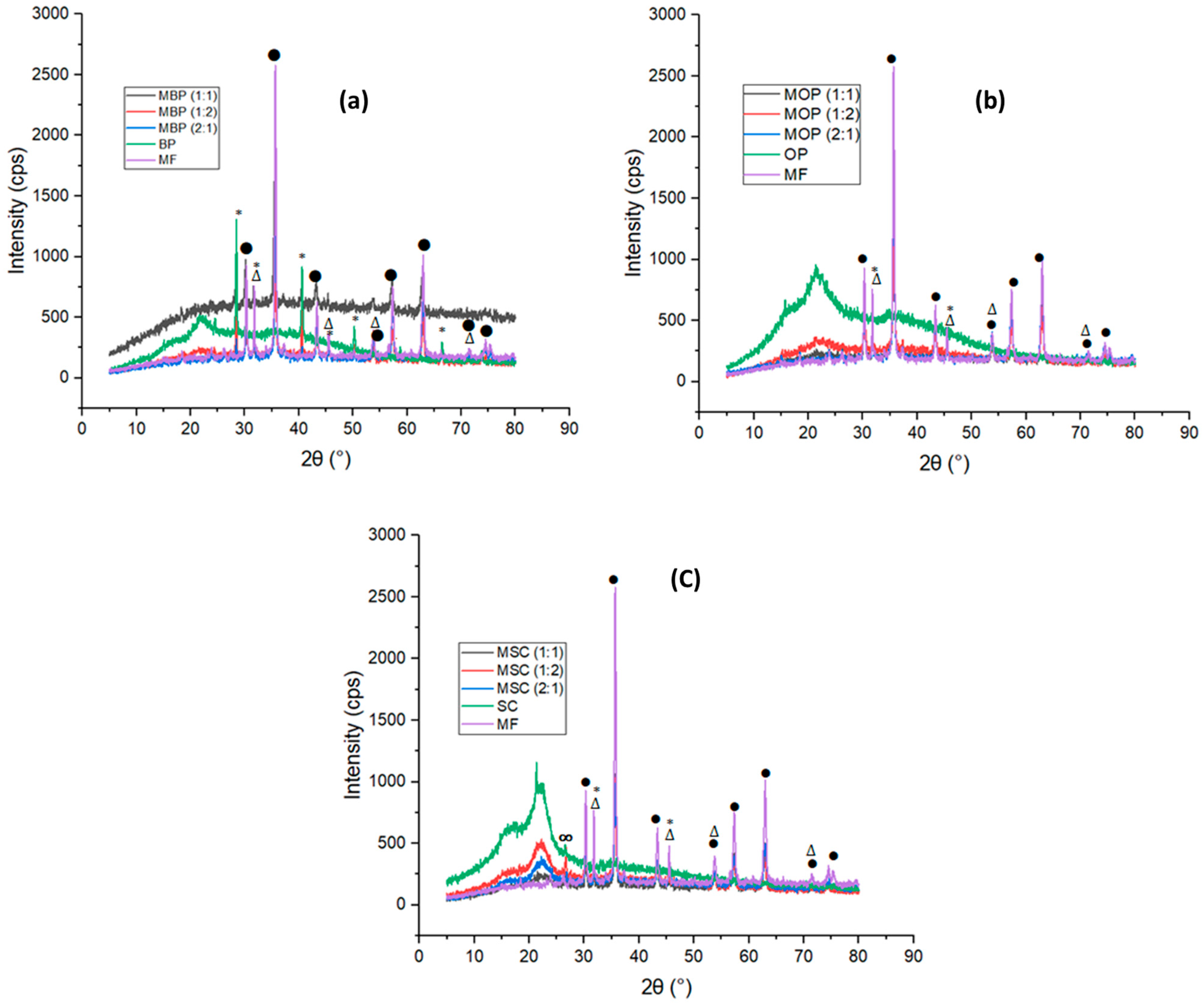

2.4.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

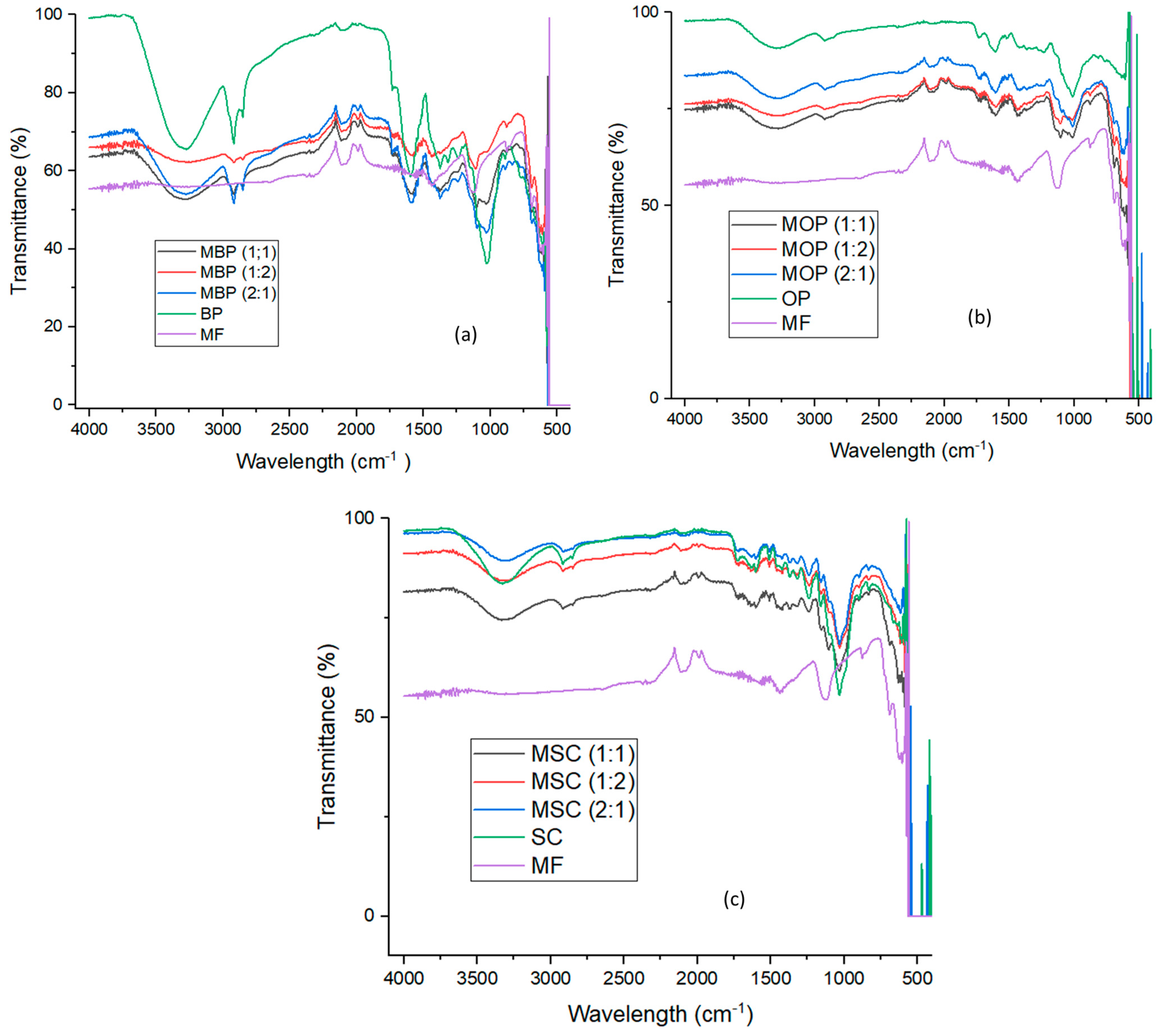

2.4.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

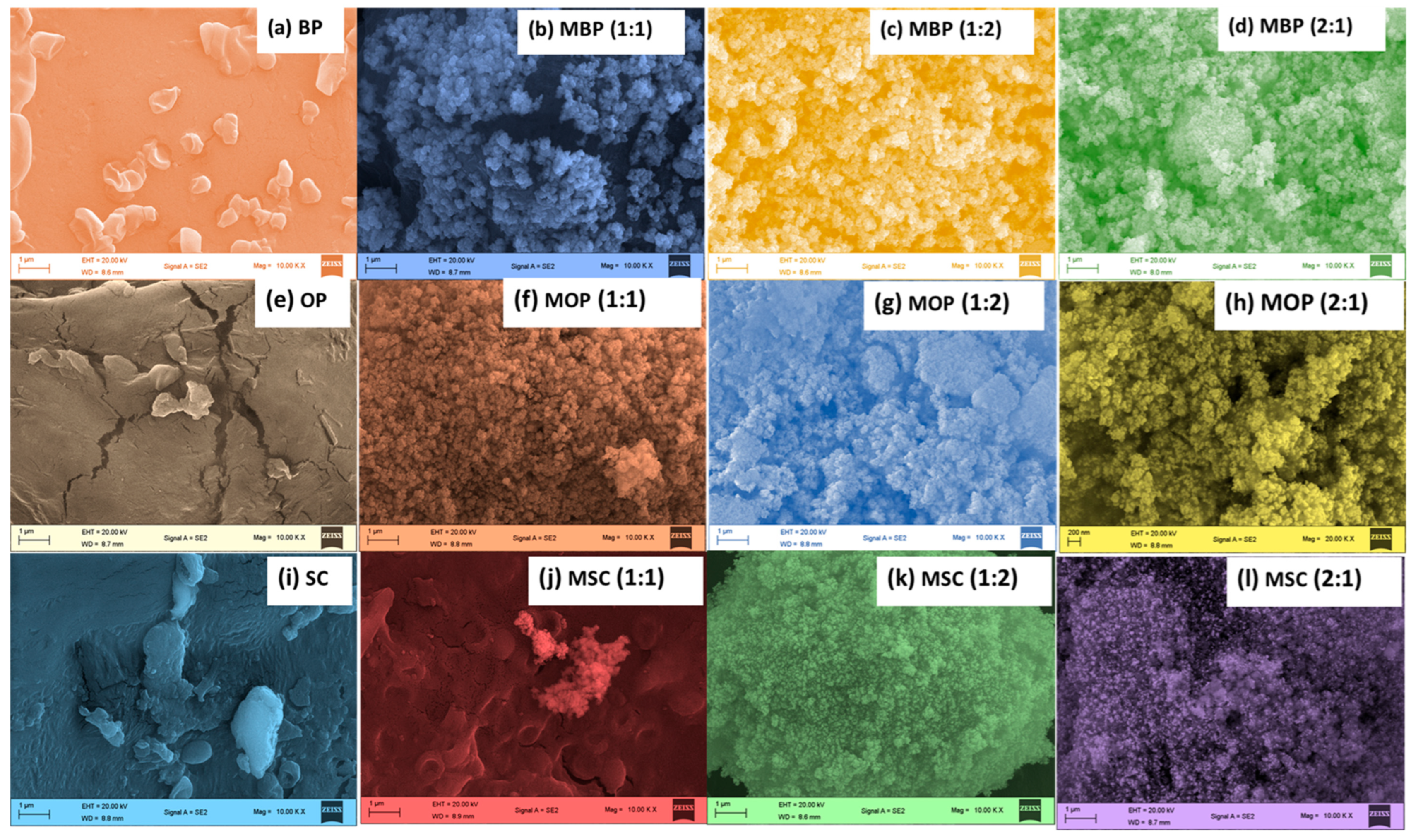

2.4.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.4.5. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET)

2.5. Adsorption Experiments

2.6. Adsorption Kinetics

2.7. Adsorption Isotherms

2.7.1. Langmuir Model

2.7.2. Freundlich Model

2.7.3. Redlich–Peterson (R-P) Model

2.7.4. Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R) Model

2.7.5. Temkin Model

3. Results

3.1. Characterization

3.1.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

3.1.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

3.1.3. FTIR Analysis

3.1.4. SEM/EDX and Surface Area Analysis

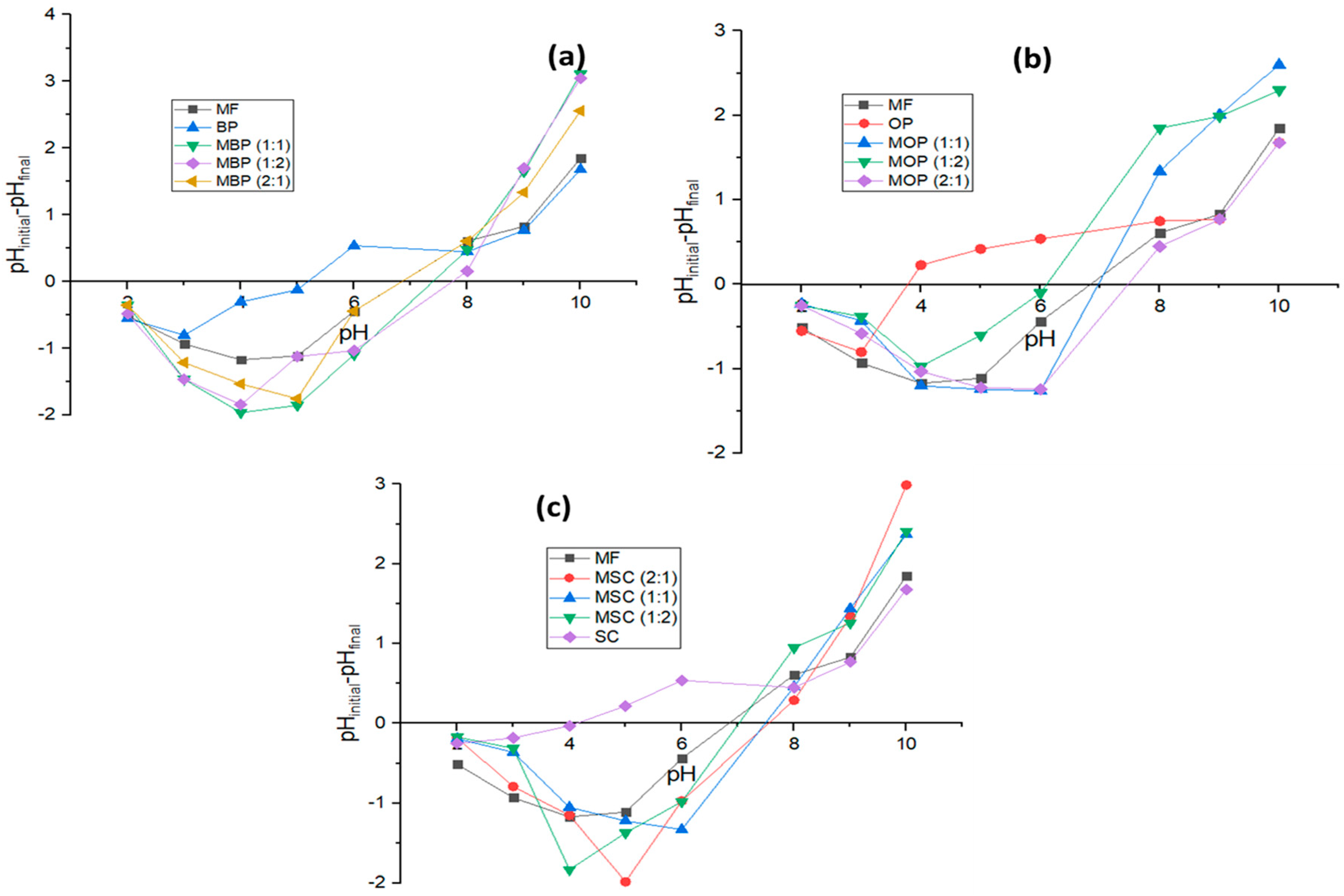

3.1.5. Point of Zero Charge (PZC)

3.2. Effect of Parameters

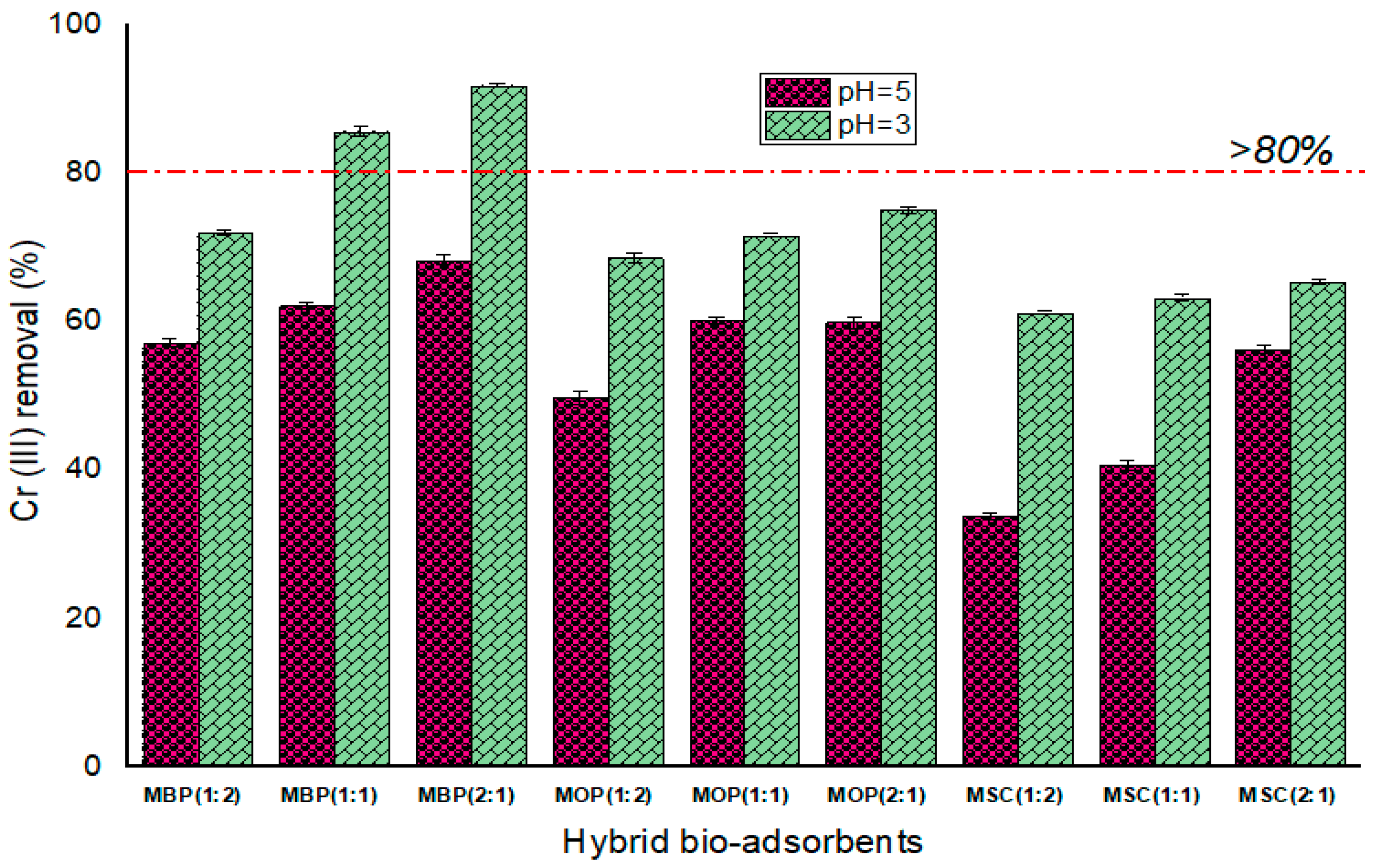

3.2.1. Performance of Hybrid Bio-Adsorbents

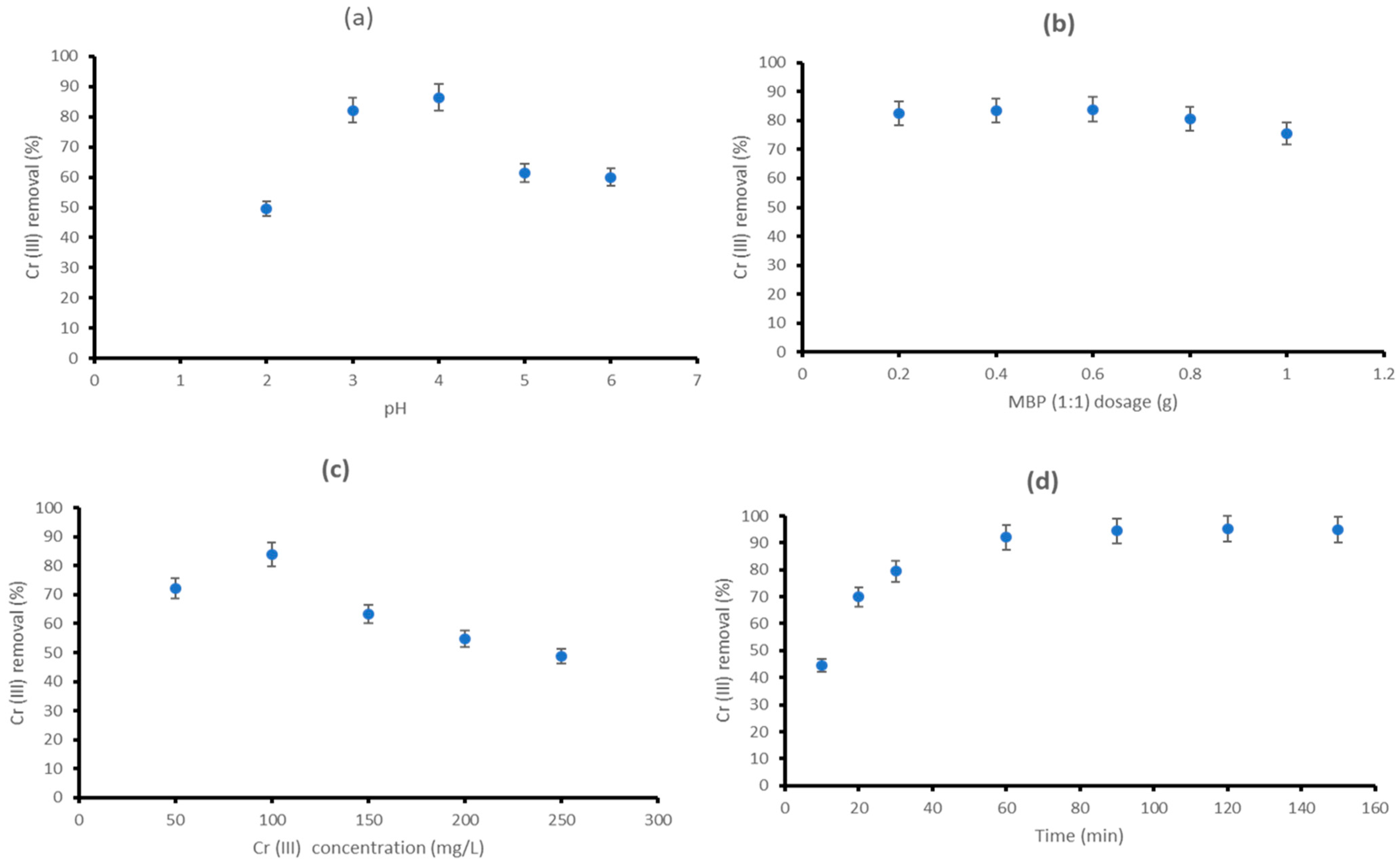

3.2.2. Effect of pH

3.2.3. Effect of MBP (1:1) Dosage

3.2.4. Effect of Initial Cr (III) Concentration

3.2.5. Effect of Contact Time

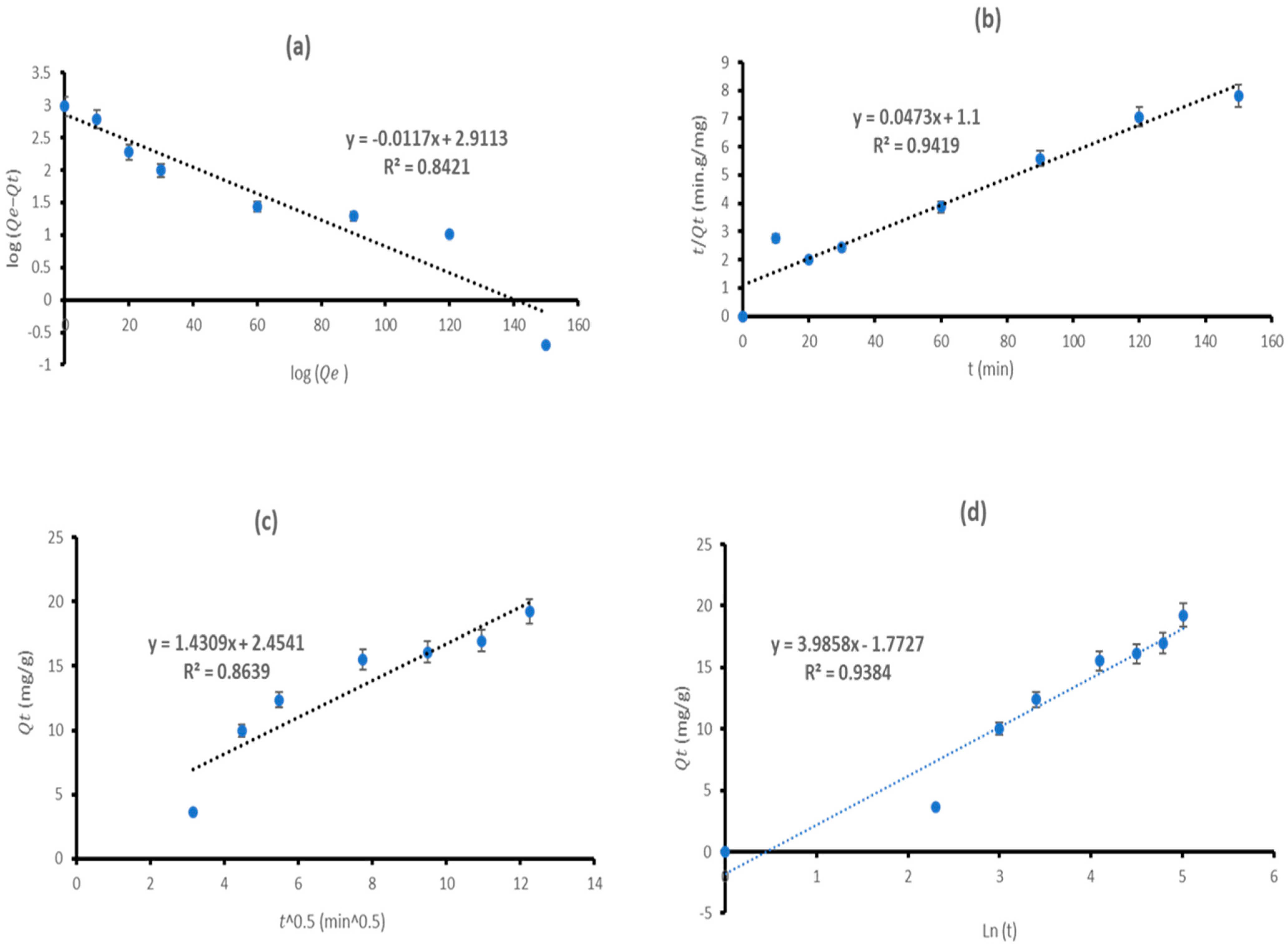

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

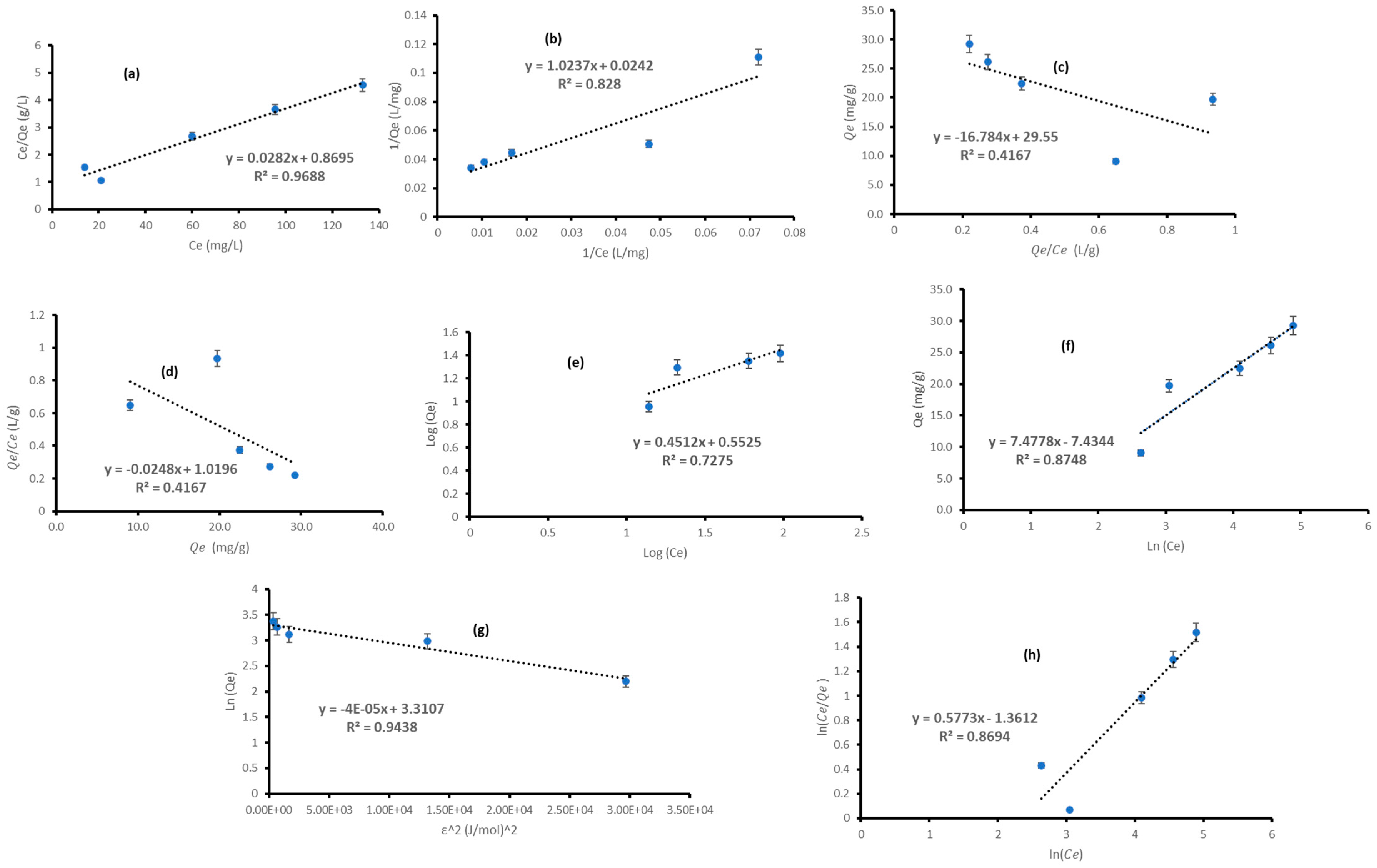

3.4. Isotherms

| Adsorbent/s | Working Conditions Efficiency | Removal Efficiency | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Best Fitted Isotherm | Kinetics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBP (1:1) | 0.4 g;100 mg/L; 60 min and pH = 3 | 92.10% | 35.46 | Langmuir | PSO | In this study |

| Sawdust (treated) | 1 g; 513.72 mg/L; 120 min and pH = 2.5; 27.5 °C | 99.27% | 4.69 | Langmuir | PSO | [42] |

| Corn husk (treated) | 99.16% | 4.70 | Langmuir | PSO | ||

| Immobilized corn cob biomass | 0.1 g; 100 mg/L, 24 hr and pH = 5; 25 °C | 64.52% | 277.57 | Langmuir | PSO | [92] |

| Pre-treated orange peel | 1 g;10 mg/L; T = 25 °C; 240 min; pH = 3 | 79% | 9.43 | Langmuir | PSO | [14] |

| Magnetic calcite | 0.5 g/L;10 g/L; T = 40 °C; 60 min; pH = 6.0 | 94% | 24.2 | Langmuir and Freundlich | PSO | [37] |

| Jackfruit peel | 0.4 g;10 g/L; T = 25 °C; 30 min | - | 13.50 | Langmuir | PSO | [98] |

| NaOH-modified peel of Artocarpus nobilis fruit | 0.2 g, 10 mg/L; 120 min and pH = 5; 25 °C | - | 4.87 | - | PSO | [71] |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bibi, M.; Behlil, F.; Afzal, S. Essential and non-essential heavy metals sources and impacts on human health and plants. Pure Appl. Biol. 2023, 12, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, G.O.; Samuel, P.O.; Oloni, G.O.; Ezekiel, G.O.; Ikpekoro, V.O.; Obasohan, P.; Ongulu, J.; Otunuya, C.F.; Opiti, A.P.; Ajakaye, R.S. Environmental persistence, bioaccumulation, and ecotoxicology of heavy metals. Chem. Ecol. 2024, 40, 322–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Xiao, B.; Ali, M.U.; Xiao, P.; Zhao, P.; Wang, H.; Bibi, S. Heavy metals pollution from smelting activities: A threat to soil and groundwater. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 274, 116189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.K.; Wang, M.-H.S. Metals and Trace Elements on Earth. In Control of Heavy Metals in the Environment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, O.S.; Agboola, O.S.; Adegoke, K.A. Sources of various heavy metal ions. In Heavy Metals in the Environment: Management Strategies for Global Pollution; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhong, W. Research on the evolution of the global import and export competition network of chromium resources from the perspective of the whole industrial chain. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R. Metallic Minerals and Their Deposits. In Geology and Mineral Resources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 495–561. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, R.T.; Mfarrej, M.F.B.; Alam, P.; Rinklebe, J.; Ahmad, P. Accumulation of chromium in plants and its repercussion in animals and humans. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 301, 119044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatua, S.; Dey, S.K. The chemistry and toxicity of chromium pollution: An overview. Asian J. Agric. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Kim, N.; Park, D. Ecotoxicity study of reduced-Cr(III) generated by Cr(VI) biosorption. Chemosphere 2023, 332, 138825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-E-Alam, M.; Mia, M.A.S.; Ahmad, F.; Rahman, M.M. An overview of chromium removal techniques from tannery effluent. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszak, K.; Kruszelnicka, I.; Ginter-Kramarczyk, D.; Góra, W.; Baraniak, M.; Lota, G.; Regel-Rosocka, M. Advances in the removal of Cr(III) from spent industrial effluents—A review. Materials 2022, 16, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Huang, X.; Yan, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ye, J.; Wei, Y. A review of the formation of Cr(VI) via Cr(III) oxidation in soils and groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Lugo, V.; Barrera-Díaz, C.; Ureña-Núñez, F.; Bilyeu, B.; Linares-Hernández, I. Biosorption of Cr(III) and Fe(III) in single and binary systems onto pretreated orange peel. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 112, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patience, D.; German, N.; Jeffrey, M.; Alowo, R. Pollution in the Urban Environment: A Research on Contaminated Groundwater in the Aquifers Beneath the Qoboza Klaaste (QK) Building at University of Johannesburg in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Construction Industry Development Board Postgraduate Research Conference, East London, South Africa, 10–12 July 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 773–782. [Google Scholar]

- Khalfaoui, A.; Benalia, A.; Selama, Z.; Hammoud, A.; Derbal, K.; Panico, A.; Pizzi, A. Removal of chromium (VI) from water using orange peel as the biosorbent: Experimental, modeling, and kinetic studies on adsorption isotherms and chemical structure. Water 2024, 16, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harboul, K.; Alouiz, I.; Hammani, K.; El-Karkouri, A. Isotherm and kinetics modeling of biosorption and bioreduction of the Cr(VI) by Brachybacterium paraconglomeratum ER41. Extremophiles 2022, 26, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibiya, N.P. Treatment of Industrial Effluent Using Specialized, Magnetized Coagulants. Master’s Thesis, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S.; Selvarajan, E.; Chidambaram, R.; Patel, H.; Brindhadevi, K. Clean approach for chromium removal in aqueous environments and role of nanomaterials in bioremediation: Present research and future perspective. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, H.; Sahoo, J.K. Iron Oxide-Based Nanocomposites and Nanoenzymes: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, P.; Ahamad, L.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, G.; Chen, W.-J.; Chen, S. Nanoparticle-mediated bioremediation as a powerful weapon in the removal of environmental pollutants. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, D.; Mousavi, S.A. A comprehensive review on the recent development of inorganic nano-adsorbents for the removal of heavy metals from water and wastewater. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 26, 33–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaenark, C.; Jantrasakul, T.; Paejaroen, P.; Chunchob, S.; Sawangproh, W. Sugarcane bagasse and corn stalk biomass as a potential sorbent for the removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solutions. Trends Sci. 2023, 20, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, A.; Nadeem, R.; Bibi, S.; Rashid, U.; Hanif, M.A.; Jahan, N.; Ashfaq, Z.; Ahmed, Z.; Adil, M.; Naz, M. Efficient adsorption of lead ions from synthetic wastewater using agrowaste-based mixed biomass (potato peels and banana peels). Water 2021, 13, 3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulaili, A.; Elsayed, K.; Refaie, A. Utilization of agriculture waste materials as sustainable adsorbents for heavy metal removal: A comprehensive review. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 12, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, E.C.; Colletti, A.; Grillo, G.; Tabasso, S.; Cravotto, G. Emerging processing technologies for the recovery of valuable bioactive compounds from potato peels. Foods 2020, 9, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewo, O.A.; Ramaila, S.; Mavuru, L.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Afolabi, F.O.; Musonge, P.; Kukwa, D.T.; Ogunjinmi, O.E. Domestic and Agricultural Wastes: Environmental Impact and Their Economic Utilization. In Agricultural and Kitchen Waste; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, B.; Saravanan, A.; Kumar, P.S.; Yaashikaa, P.; Thamarai, P.; Shaji, A.; Rangasamy, G. A review on algae biosorption for the removal of hazardous pollutants from wastewater: Limiting factors, prospects and recommendations. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 327, 121572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, F.O.; Musonge, P.; Bakare, B.F. Adsorption of copper and lead ions in a binary system onto orange peels: Optimization, equilibrium, and kinetic study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.S. The UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) are a great gift to business! Procedia Cirp 2018, 69, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channei, D.; Jannoey, P.; Thammaacheep, P.; Khanitchaidecha, W.; Nakaruk, A. From Waste to Value: Banana-Peel-Derived Adsorbents for Efficient Removal of Polar Compounds from Used Palm Oil. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, F.O.; Musonge, P. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biosorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ Ions from an Aqueous Solution Using Biochar Derived from Orange Peels. Molecules 2023, 28, 7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrou, M.; Bouslamti, N.; Raada, A.; Elanssari, A.; Mrani, D.; Slimani, M. The Use of Sugarcane Bagasse to Remove the Organic Dyes from Wastewater. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5570806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibiya, N.P.; Rathilal, S.; Kweinor Tetteh, E. Coagulation treatment of wastewater: Kinetics and natural coagulant evaluation. Molecules 2021, 26, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameha, B.; Nadew, T.T.; Tedla, T.S.; Getye, B.; Mengie, D.A.; Ayalneh, S. The use of banana peel as a low-cost adsorption material for removing hexavalent chromium from tannery wastewater: Optimization, kinetic and isotherm study, and regeneration aspects. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 3675–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dada, A.; Inyinbor, A.; Tokula, B.; Ajanaku, C.; Ayo-Akere, S.; Latona, D.; Ajanaku, K. Sustainable Chitosan Supported Magnetite Nanocomposites for Sequestration of Rhodamine B Dye from the Environment. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1342, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.J.; Varalakshmi, R.; Gargi, S.; Jayasri, M.; Suthindhiran, K. Removal of Cr (III) and Ni (II) from tannery effluent using calcium carbonate coated bacterial magnetosomes. NPJ Clean Water 2018, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlayıcı, Ş.; Baran, Y. Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions using nano-Fe3O4/waste banana peel/alginate hydrogel biobeads as adsorbent. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 18695–18721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, Y.M.; Altaher, H.; ElQada, E. Removal of three nitrophenols from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto char ash: Equilibrium and kinetic modeling. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgel, J.J.D.T.; Briones, J.M.A.; Diaz, E.B., Jr.; Dimaculangan, K.M.N.; Rangel, K.L.; Lopez, E.C.R. Removal of diesel oil from water using biochar derived from waste banana peels as adsorbent. Carbon Res. 2024, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusain, D.; Sahani, S.; Sharma, Y.; Han, S. Adsorption of cadmium ion from water by using non-toxic iron oxide adsorbent; experimental and statistical modelling analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Hameed, S.; Abbasi, N.A.; Liaqat, I.; Rasheed, R.; Khan, A.A.; Manan, H.a. Removal of Cr (III) from wastewater by using raw and chemically modified sawdust and corn husk. Water Pract. Technol. 2022, 17, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.V.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, Q.T.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Van Pham, T.; Nguyen, T.D. Linearized and nonlinearized modellings for comparative uptake assessment of metal-organic framework-derived nanocomposite towards sulfonamide antibiotics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 63448–63463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, A.; Narayanan, N.; Varghese, E.; Gupta, S. Linear and nonlinear isotherm models and error analysis for the sorption of kresoxim-methyl in agricultural soils of India. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 104, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, S.M.; Bakare, B.F.; Rathilal, S. Single and multicomponent adsorption of amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, and sulfamethoxazole on chitosan-carbon nanotubes hydrogel beads from aqueous solutions: Kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamic parameters. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 13, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; Lima, E.C.; Juang, R.-S.; Bollinger, J.-C.; Chao, H.-P. Thermodynamic parameters of liquid–phase adsorption process calculated from different equilibrium constants related to adsorption isotherms: A comparison study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, A.; Bouziane, N.; Bendjeffal, H.; Bouhedja, Y.; Zertal, A. Biosorption of some pharmaceutical compounds from aqueous medium by Luffa cylindrica fibers: Application of the linear form of the redlich-peterson isotherm equation. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 214, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrudin, N.; Nawi, M.; Lelifajri. Kinetics and isotherm modeling of phenol adsorption by immobilizable activated carbon. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2019, 126, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Correction to the calculation of Polanyi potential from Dubinnin-Rudushkevich equation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayuo, J.; Pelig-Ba, K.B.; Abukari, M.A. Isotherm modeling of lead (II) adsorption from aqueous solution using groundnut shell as a low-cost adsorbent. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 2018, 11, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, B.; Mânzatu, C.; Măicăneanu, A.; Indolean, C.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Majdik, C. Linear and nonlinear regression analysis for heavy metals removal using Agaricus bisporus macrofungus. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S3569–S3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Reguyal, F.; Praneeth, S.; Sarmah, A.K. A novel green synthesized magnetic biochar from white tea residue for the removal of Pb (II) and Cd (II) from aqueous solution: Regeneration and sorption mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 330, 121806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Ma, J. Novel synthesis of carbon spheres supported nanoscale zero-valent iron for removal of metronidazole. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 390, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, N.; Afzaal, M.; Niaz, B.; Saeed, F.; Nosheen, F.; Khan, M.A.; Hussain, M.; Raza, M.A.; Imran, M.; Jbawi, E.A. Structural and functional investigations of wall material extracted from banana peels. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Prabhakar, B.; Kharkar, P.S.; Pethe, A.M. Banana Peel Waste: An Emerging Cellulosic Material to Extract Nanocrystalline Cellulose. ACS Omega 2022, 8, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, J.A.A.; Lagos, S.N.P.; Sanchez, E.J.E.; Rivera-Flores, O.; Sánchez-Barahona, M.; Guerrero, A.; Romero, A. Innovative agrowaste banana peel extract-based magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for eco-friendly oxidative shield and freshness fortification. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 5083–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sareji, O.J.; Grmasha, R.A.; Meiczinger, M.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Somogyi, V.; Hashim, K.S. A sustainable banana peel activated carbon for removing pharmaceutical pollutants from different waters: Production, characterization, and application. Materials 2024, 17, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, A.O.; Musonge, P. Synthesis of a Highly Efficient Mesoporous Green Catalyst from Waste Avocado Peels for Biodiesel Production from Used Cooking–Baobab Hybrid Oil. Catalysts 2024, 14, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arregui-Almeida, D.; Coronel, M.; Analuisa, K.; Bastidas-Caldes, C.; Guerrero, S.; Torres, M.; Aluisa, A.; Debut, A.; Brämer-Escamilla, W.; Pilaquinga, F. Banana fruit (Musa sp.) DNA-magnetite nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and biocompatibility assays on normal and cancerous cells. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolabi, F.O.; Musonge, P.; Bakare, B.F. Bio-sorption of a bi-solute system of copper and lead ions onto banana peels: Characterization and optimization. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, H.; Mansoor, M.A.; Haider, B.; Nasir, R.; Hamid, S.B.A.; Abdulrahman, A. Synthesis and characterization of magnetite nano particles with high selectivity using in-situ precipitation method. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 207–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.; Dey, A.; Bomans, P.H.; Le Coadou, C.; Fratzl, P.; Sommerdijk, N.A.; Faivre, D. Nucleation and growth of magnetite from solution. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcharoen, K.; Sirivat, A. Synthesis and characterization of magnetite nanoparticles via the chemical co-precipitation method. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2012, 177, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, N. Preparation of biocompatible magnetite-carboxymethyl cellulose nanocomposite: Characterization of nanocomposite by FTIR, XRD, FESEM and TEM. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 131, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, F.O.; Musonge, P.; Bakare, B.F. Evaluation of lead (II) removal from wastewater using banana peels: Optimization study. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. Vol. 2021, 30, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Mondal, M.M.; Weichgrebe, D. Biochar from co-pyrolysis of urban organic wastes—Investigation of carbon sink potential using ATR-FTIR and TGA. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 12, 4729–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davaritouchaee, M.; Mosleh, I.; Dadmohammadi, Y.; Abbaspourrad, A. One-Step Oxidation of Orange Peel Waste to Carbon Feedstock for Bacterial Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate. Polymers 2023, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalia, A.; Derbal, K.; Khalfaoui, A.; Bouchareb, R.; Panico, A.; Gisonni, C.; Crispino, G.; Pirozzi, F.; Pizzi, A. Use of Aloe vera as an organic coagulant for improving drinking water quality. Water 2021, 13, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, K.; Bharath, G.; Banat, F.; Show, P.L. Biosorption performance of date palm empty fruit bunch wastes for toxic hexavalent chromium removal. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaraweera, A.; Priyantha, N.; Gunathilake, W.; Kotabewatta, P.; Kulasooriya, T. Biosorption of Cr (III) and Cr (VI) species on NaOH-modified peel of Artocarpus nobilis fruit. 1. Investigation of kinetics. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karn, A.; Thakur, S.; Shrestha, B. Extraction and characterization of cellulose from agricultural residues: Wheat straw and sugarcane bagasse. J. Nepal Chem. Soc. 2022, 43, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, I.; Pratama, A.W.; Amalia, R.; Wahab, I.A.; Qolbi, N.S.; Putri, B.A.; Fachri, B.A.; Palupi, B.; Fitriana, M.R.; Reza, M. Solvothermal synthesis of sugarcane bagasse-bentonite-magnetite nanocomposite for efficient Cr (VI) removal from electroplating wastewater: Kinetics and isotherm investigations. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praipipat, P.; Ngamsurach, P.; Joraleeprasert, T. Synthesis, characterization, and lead removal efficiency of orange peel powder and orange peel powder doped iron (III) oxide-hydroxide. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-T.; Chen, J.-D.; Wei, Z.-H.; Chen, Y.-K. Copper ion removal from aqueous media using banana peel biochar/Fe3O4/branched polyethyleneimine. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 658, 130736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiya, N.P.; Amo-Duodu, G.; Tetteh, E.K.; Rathilal, S. Magnetic field effect on coagulation treatment of wastewater using magnetite rice starch and aluminium sulfate. Polymers 2022, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, A.O. Characterization and Partial Purification of Pectinase Produced by Aspergillus niger Using Banana Peel as Carbon Source. Master’s Thesis, Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria, 2019. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/474b6ae1c0692a0a4f9d6ecdae26e885/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Oladipo, A.A.; Ahaka, E.O.; Gazi, M. High adsorptive potential of calcined magnetic biochar derived from banana peels for Cu2+, Hg2+, and Zn2+ ions removal in single and ternary systems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 31887–31899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo-Duodu, G.; Tetteh, E.K.; Sibiya, N.P.; Rathilal, S.; Chollom, M.N. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic nanoparticles via co-precipitation: Application and assessment in anaerobic digested wastewater. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2024, 18, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.V.; Morelli, M.R. Effect of calcination temperature on the pozzolanic activity of Brazilian sugar cane bagasse ash (SCBA). Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiya-Dlomo, N.P.; Monama, T.P.; Govender, A.; Rathilal, S. Reduction of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions from synthetic wastewater utilizing magnetic adsorbent derived from banana peels: Kinetic and Isotherm analyses. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 12, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, Z.; Khalid, Z.; Arif, S.; Waseem, M.; Haq, S. Highly Ordered and Uniform Growth of Magnetite Nanoparticles on the Surface of Amberlyst-15: Lead Ions Removal Study. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 35, 3182–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, D.H.; Andrade, J.G.S.; Porto, C.E.; Batistela, R. Valorization of agro-industrial wastes of sugarcane bagasse and rice husk for biosorption of Yellow Tartrazine dye. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2024, 96, e20231308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, D.; Gandhimathi, R. Zinc Ions adsorption from aqueous solution using raw and acid-modified orange peels: Kinetics, Isotherm, Thermodynamics, and Adsorption mechanism. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, E.; Lopes, C.B.; Vale, C.; Pereira, E.; Silva, C.M. Valuation of banana peels as an effective biosorbent for mercury removal under low environmental concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 135883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Ma, F. Enhanced hexavalent chromium removal performance and stabilization by magnetic iron nanoparticles assisted biochar in aqueous solution: Mechanisms and application potential. Chemosphere 2018, 207, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Deng, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Hou, K.; Zeng, G. Stabilization of nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) with modified biochar for Cr(VI) removal from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 332, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, A.; Bagchi, M.; Preuss, H.; Zafra-Stone, S.; Ahmad, T.; Bagchi, D. Benefits of chromium (III) complexes in animal and human health. In The Nutritional Biochemistry of Chromium (III); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 251–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H. Removal of aqueous Cr (VI) by tea stalk biochar supported nanoscale zero-valent iron: Performance and mechanism. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiana, I.G.M.N.; Jasman, J.; Neolaka, Y.A.; Riwu, A.A.; Elmsellem, H.; Darmokoesoemo, H.; Kusuma, H.S. Synthesis, characterization and application of cinnamoyl C-phenylcalix[4]resorcinarene (CCPCR) for removal of Cr(III) ion from the aquatic environment. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 324, 114776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tian, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, T.; Ni, X.; Wu, Y.-H. Carbon fiber-based flow-through electrode system (FES) for Cr(VI) removal at near neutral pHs via Cr(VI) reduction and in-situ adsorption of Cr(III) precipitates. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 127622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, Q.; Sajid, A.; Hussain, T.; Iqbal, M.; Abbas, M.; Nisar, J. Efficiency of immobilized Zea mays biomass for the adsorption of chromium from simulated media and tannery wastewater. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, G.; Hirayama, S.; Van Nguyen, B.; Lei, Z.; Shimizu, K.; Zhang, Z. Insight into Cr(VI) biosorption onto algal-bacterial granular sludge: Cr(VI) bioreduction and its intracellular accumulation in addition to the effects of environmental factors. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Sukla, L.; Mishra, B.; Devi, N. Biosorption for removal of hexavalent chromium using microalgae Scenedesmus sp. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, L.; Ma, H.; Zhou, F.; Yang, K.; Wu, G. Corn stalk-based activated carbon synthesized by a novel activation method for high-performance adsorption of hexavalent chromium in aqueous solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 578, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, M.B. Batch sorption experiments: Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm studies for the adsorption of textile metal ions onto teff straw (Eragrostis tef) agricultural waste. J. Thermodyn. 2013, 2013, 375830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.S.; Almeida, I.L.; Rezende, H.C.; Marcionilio, S.M.; Léon, J.J.; de Matos, T.N. Elucidation of mechanism involved in adsorption of Pb(II) onto lobeira fruit (Solanum lycocarpum) using Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin isotherms. Microchem. J. 2018, 137, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, S.; Navaratne, A.; Priyantha, N. Enhancement of adsorption characteristics of Cr(III) and Ni(II) by surface modification of jackfruit peel biosorbent. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5670–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HB Ratio/(s) | MOP | MBP | MSC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF (g) | OP (g) | MF (g) | BP (g) | MF (g) | SC (g) | |

| 1:1 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| 1:2 | 16.67 | 33.33 | 16.67 | 33.33 | 16.67 | 33.33 |

| 2:1 | 33.33 | 16.67 | 33.33 | 16.67 | 33.33 | 16.67 |

| Sample/s | Surface Area (m2/g) | C | O | K | S | Ca | Fe | P | Si | Na | Cl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MF | 38.1951 | 9.51 ± 0.57 | 33.07 ± 0.32 | - | 6.87 ± 0.11 | - | 36.48 ± 0.32 | - | - | 13.80 ± 0.20 | 0.25 ± 0.04 |

| BP | 3.6689 | 54.54 ± 0.44 | 32.78 ± 0.39 | 11.71 ± 0.13 | - | 0.21 ± 0.05 | - | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.05 | - |

| OP | 2.7196 | 73.58 ± 0.46 | 18.89 ± 0.43 | 4.43 ± 0.09 | - | 1.85 ± 0.07 | - | 0.95 ± 0.09 | 0.10 ± 0.09 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | - |

| SC | 1.8891 | 65.76 ± 0.37 | 30.47 ± 0.36 | 2.20 ± 0.02 | - | 0.40 ± 0.02- | - | 0.35 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.13- | - |

| MBP (1:1) | 47.5190 | 17.58 ± 0.46 | 31.22 ± 0.36 | 6.95 ± 0.08 | - | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 34.01 ± 0.07 | - | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 5.92 ± 0.09 | 3.28 ± 0.05 |

| MBP (1:2) | 34.9912 | 15.78 ± 0.66 | 22 ± 0.27 | 1.34 ± 0.05 | - | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 57.49 ± 0.07 | - | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 2.08 ± 0.12 | 1.12 ± 0.05 |

| MBP (2:1) | 48.1893 | 8.24 ± 0.77 | 37.20 ± 0.41 | 7.46 ± 0.11 | 0.03 ± 0.15 | 38.05 ± 0.39 | - | 4.80 ± 0.09 | 4.03 ± 0.13 | 0.19 ± 0.11 | |

| MOP (1:1) | 31.9438 | 16.90 ± 0.44 | 22.34 ± 0.24 | 9.02 ± 0.39- | - | - | 50.15 ± 0.39 | - | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.04 |

| MOP (1:2) | 30.7021 | 8.36 ± 0.69 | 31.62 ± 0.33 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | - | - | 59.45 ± 0.50 | - | 0.15 ± 0.04 | - | 0.28 ± 0.04 |

| MOP (2:1) | 39.1918 | 16.01 ± 0.65 | 27.42 ± 0.31 | 0.20 ± 0.04- | - | - | 55.36 ± 0.49 | - | 0.27 ± 0.04 | - | 0.74 ± 0.04 |

| MSC (1:1) | 28.2011 | 19.28 ± 0.67 | 28.83 ± 0.40 | 0.05 ± 0.03- | - | - | 51.24 ± 0.40 | - | 0.35 ± 0.04 | - | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| MSC (1:2) | 20.8773 | 13.91 ± 0.46 | 26.38 ± 0.26 | 0.03 ± 0.04- | - | - | 59.49 ± 0.38 | - | - | - | 0.19 ± 0.04 |

| MSC (2:1) | 30.15291 | 10.01 ± 0.44 | 22.49 ± 0.24 | 0.89 ± 0.10 | - | - | 65.83 ± 0.39 | - | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.04 |

| Kinetic Model | Coefficients | Value |

|---|---|---|

| PFO | 819.0304 | |

| 0.0269 | ||

| 0.8421 | ||

| PSO | 21.1416 | |

| 0.0020 | ||

| 0.9419 | ||

| Intra-particle | 16.0288 | |

| 1.4309 | ||

| C | 2.4541 | |

| 0.8639 | ||

| Elovich | 16.1590 | |

| 2.5541 | ||

| 0.2509 | ||

| 0.9384 |

| Isotherm Model | Isotherms Parameter/(s) | Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 | Type 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | 35.4610 | 41.3223 | 29.5500 | 41.1129 | |

| 0.0325 | 0.0236 | 0.0596 | 0.0248 | ||

| 0.2357 | 0.2973 | 0.1437 | 0.2874 | ||

| 0.9688 | 0.8280 | 0.4167 | 0.4167 | ||

| Freundlich | 3.5686 | ||||

| 0.4512 | |||||

| 2.2163 | |||||

| 0.7275 | |||||

| Temkin | 0.3700 | ||||

| 331.4904 | |||||

| 0.8748 | |||||

| D-R | 27.4043 | ||||

| 0.00004 | |||||

| (J/mol) | 114.7806 | ||||

| 0.9438 | |||||

| R-P | 3.9009 | ||||

| 0.5773 | |||||

| 0.8694 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sibiya-Dlomo, N.P.; Cebekhulu, S.; Monama, T.P.; Rathilal, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Bio-Adsorbents for the Biosorption of Chromium Ions from Aqueous Solutions. Polymers 2026, 18, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010120

Sibiya-Dlomo NP, Cebekhulu S, Monama TP, Rathilal S. Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Bio-Adsorbents for the Biosorption of Chromium Ions from Aqueous Solutions. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleSibiya-Dlomo, Nomthandazo Precious, Sakhile Cebekhulu, Thembisile Patience Monama, and Sudesh Rathilal. 2026. "Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Bio-Adsorbents for the Biosorption of Chromium Ions from Aqueous Solutions" Polymers 18, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010120

APA StyleSibiya-Dlomo, N. P., Cebekhulu, S., Monama, T. P., & Rathilal, S. (2026). Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid Bio-Adsorbents for the Biosorption of Chromium Ions from Aqueous Solutions. Polymers, 18(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010120