Characteristics of Particleboards Made from Esterified Rattan Skin Particles with Glycerol–Citric Acid: Physical, Mechanical, Chemical, and Durability Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Poly-Esterification of Rattan Skins

2.3. Particleboard Production

2.4. Characterization

2.4.1. Physical Properties

Moisture Content

Density

Color Characteristics

Thickness Swelling

Water Absorption

2.4.2. Mechanical Properties

Modulus of Elasticity and Modulus of Rupture

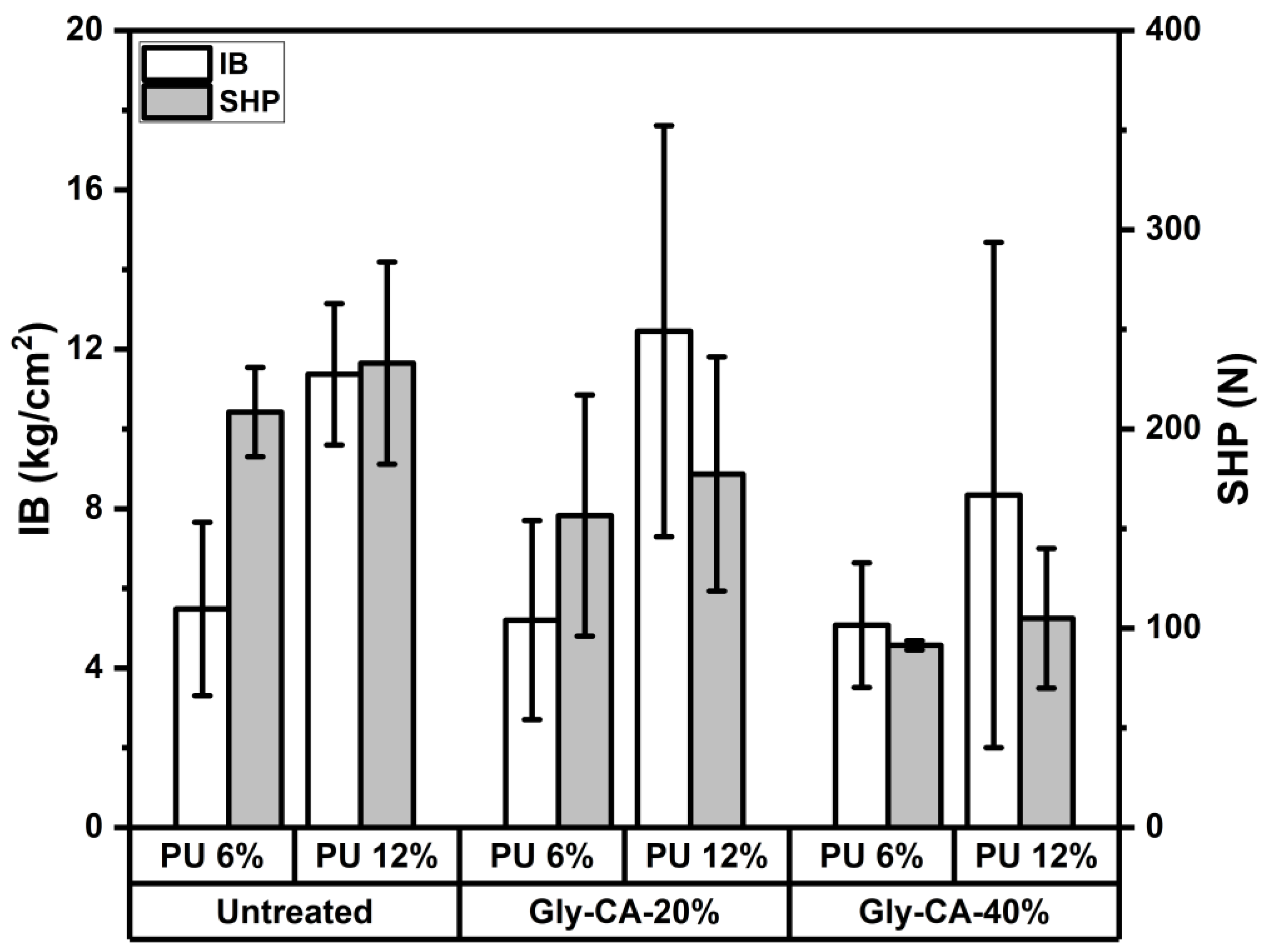

Internal Bonding

Screw Holding Strength

2.4.3. Chemical Properties

Fourier Transform Infrared

Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.4.4. Field Test Study

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

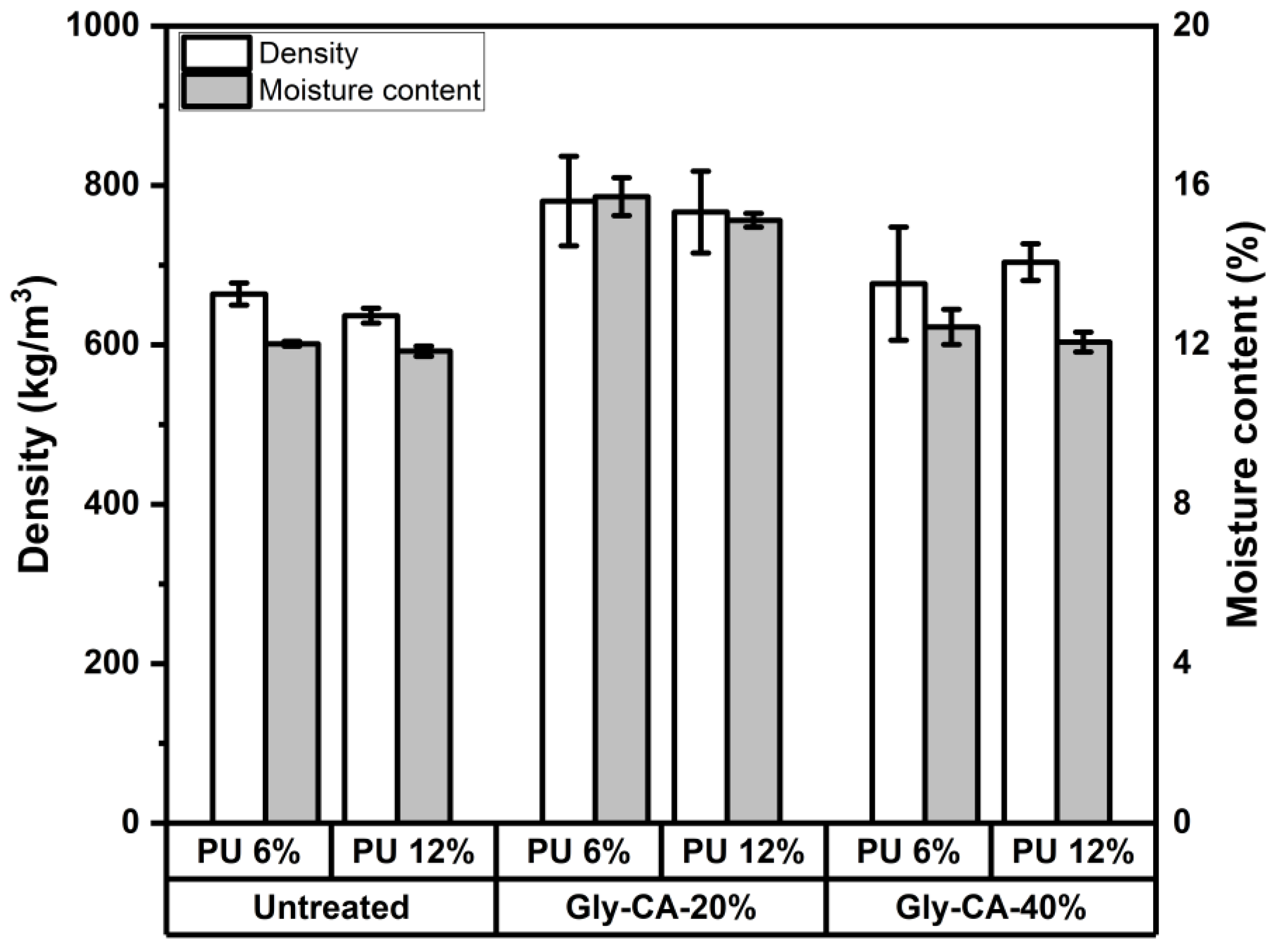

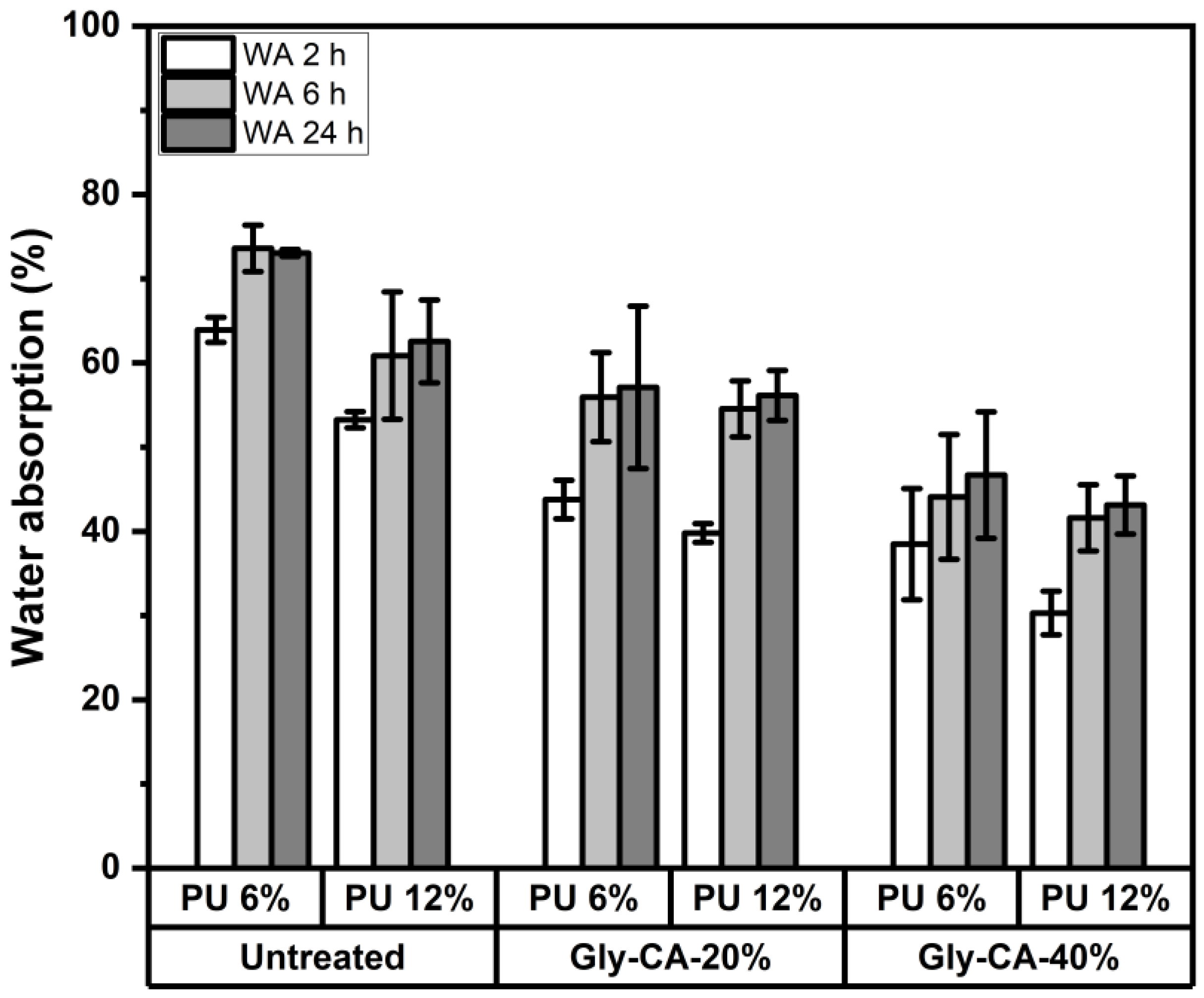

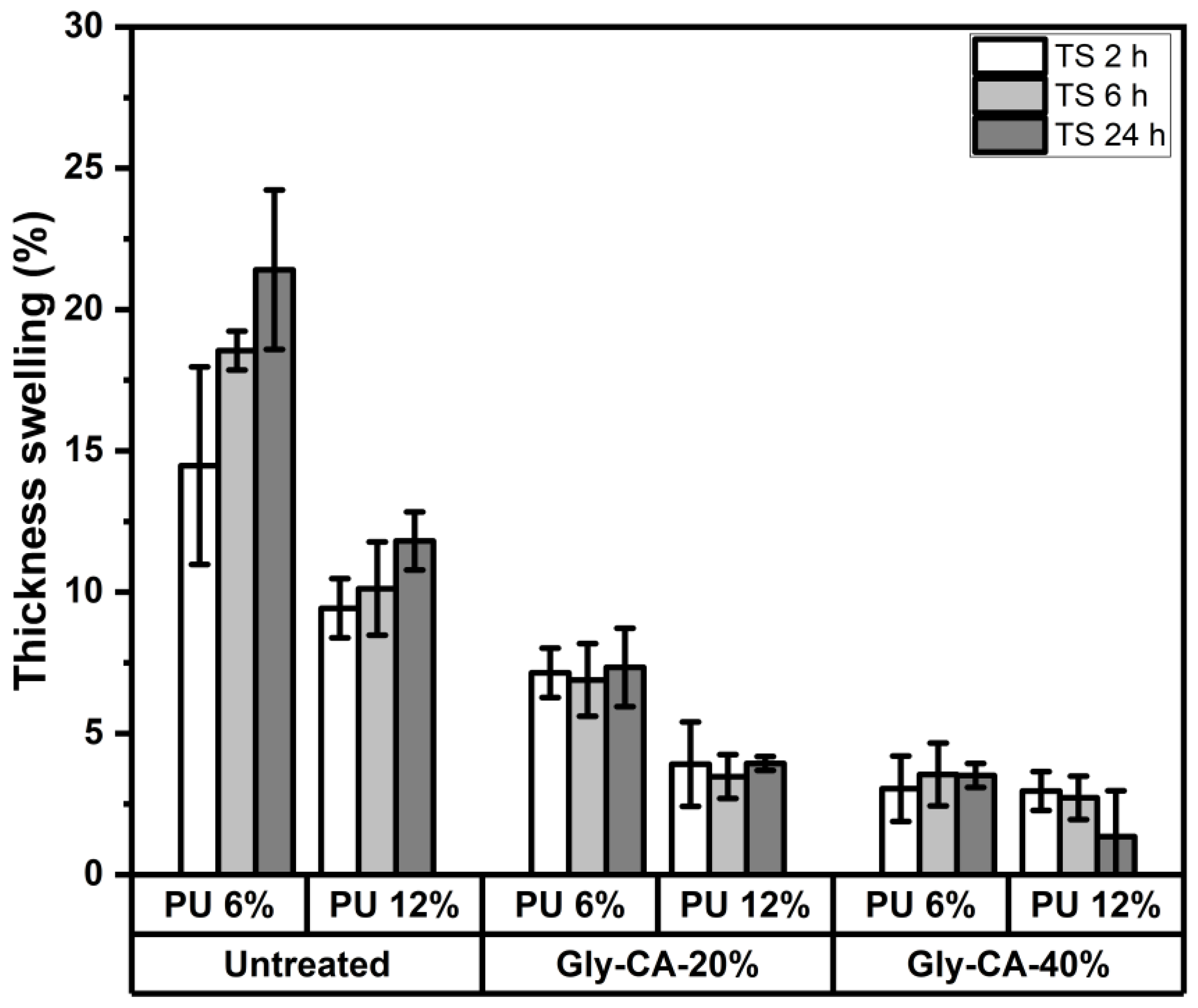

3.1. Physical Properties

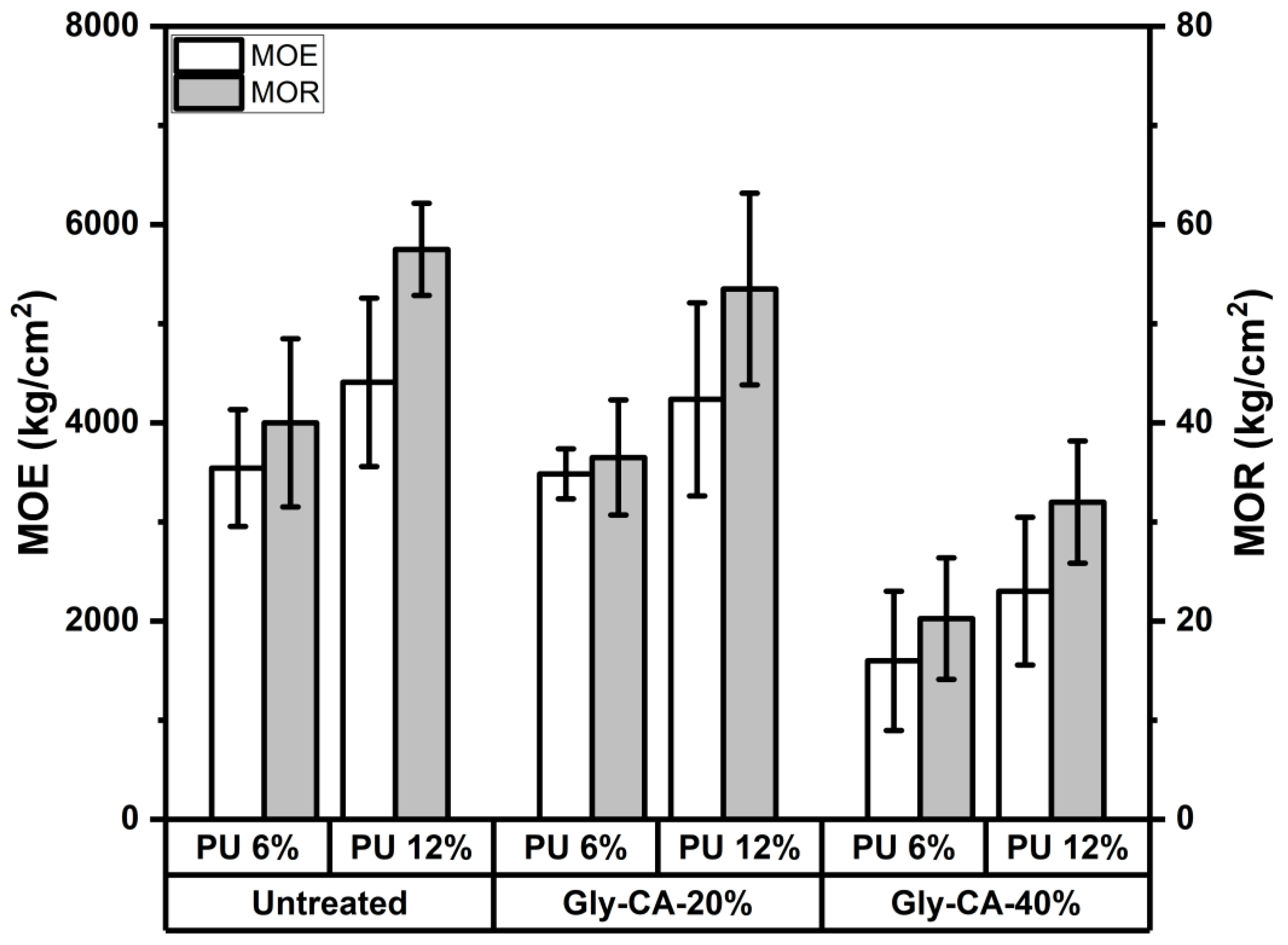

3.2. Mechanical Properties

3.3. Chemical Properties

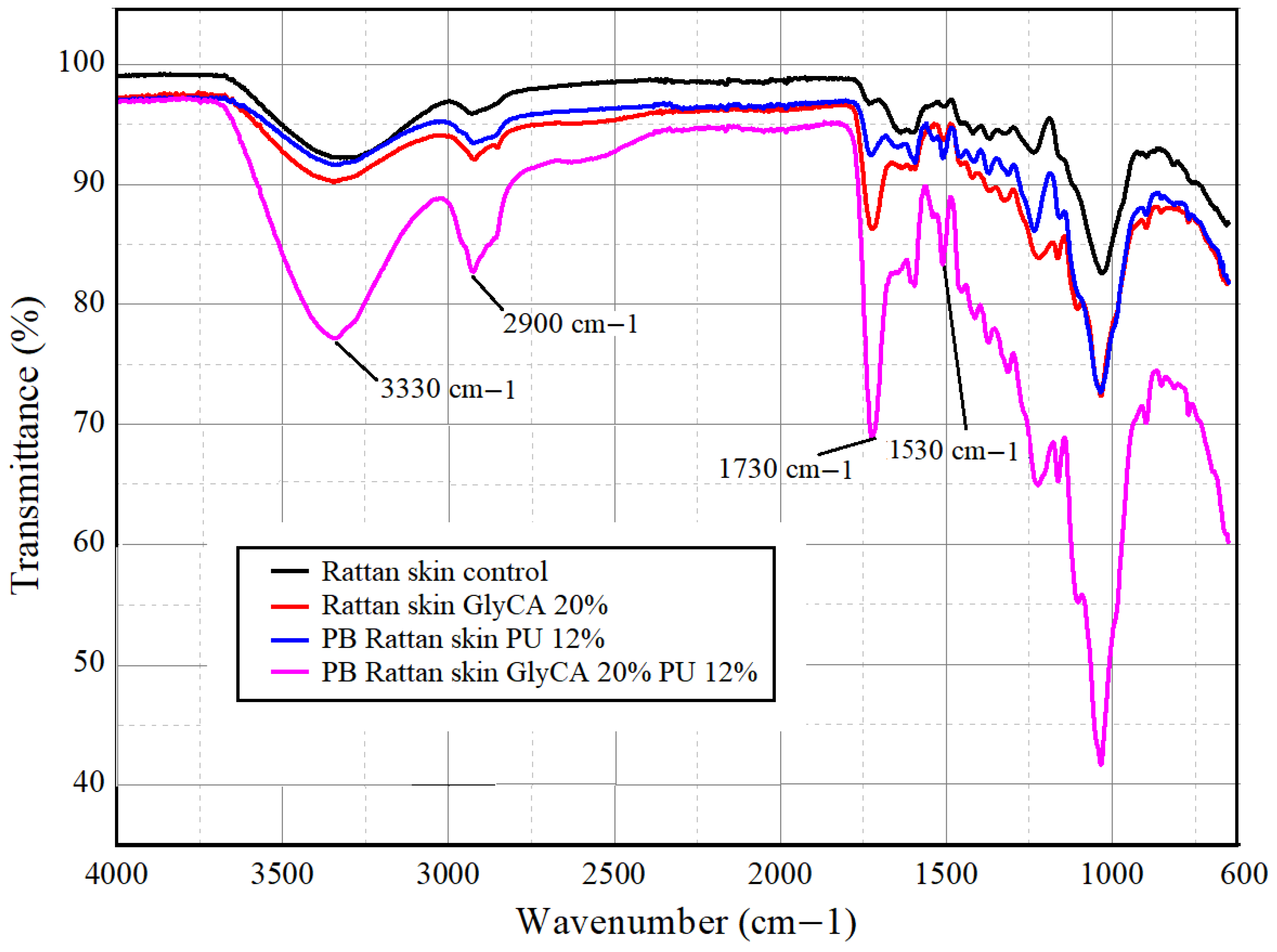

3.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

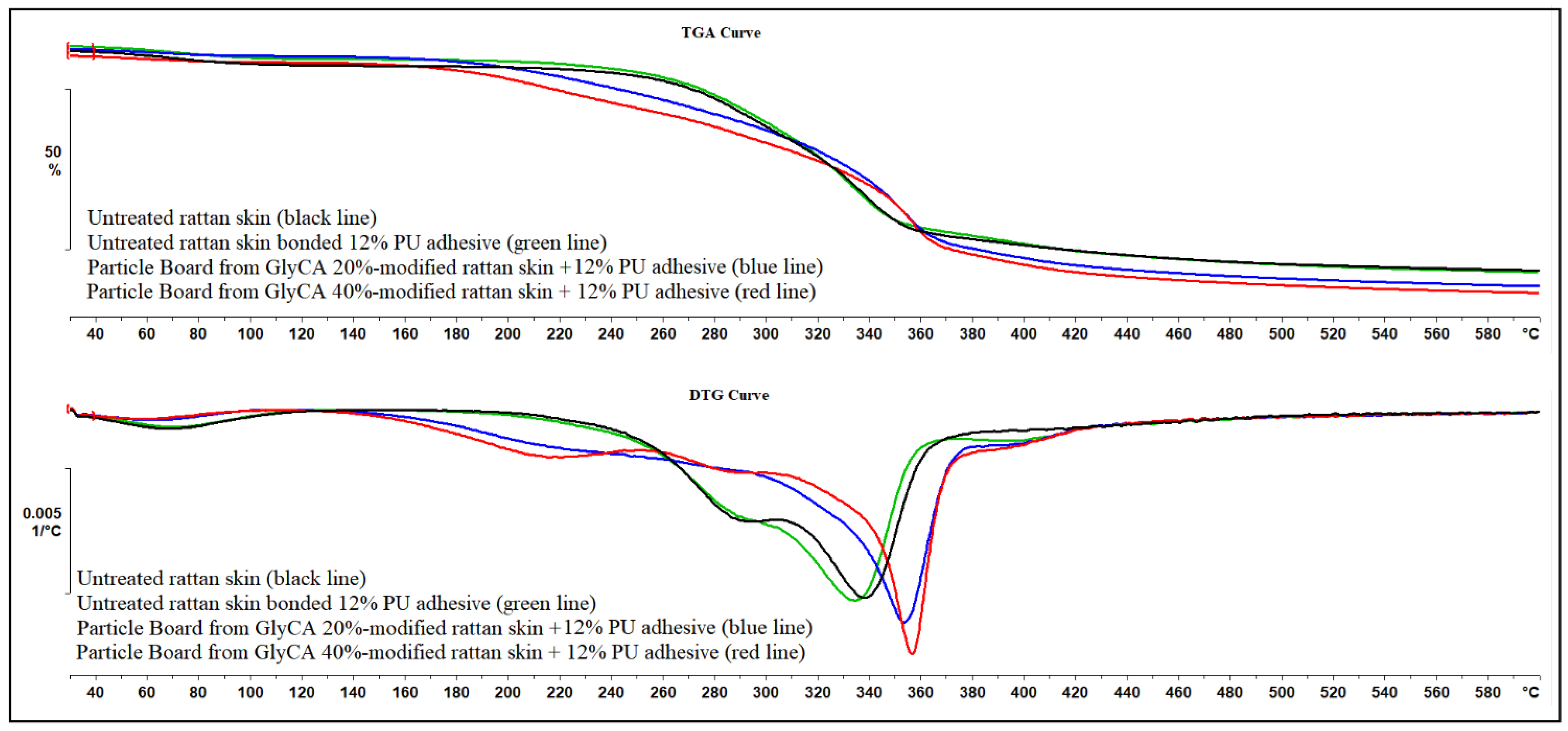

3.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis

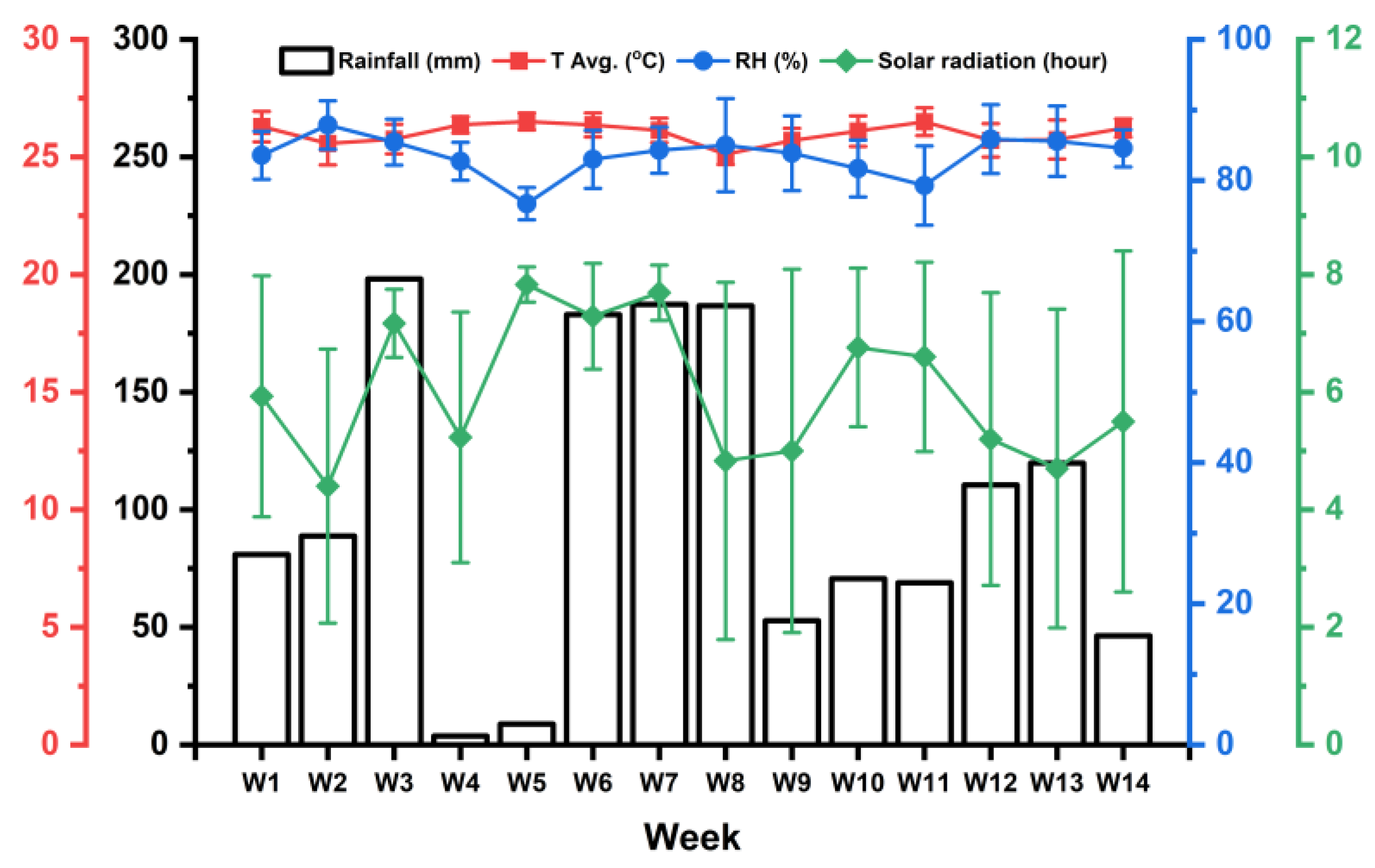

3.4. Field Test Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfathi, B.R. Perkembangan Produksi Batang Rotan Indonesia (2019–2023). 2024. Available online: https://data.goodstats.id/statistic/luas-deforestasi-di-sumatra-tembus-78-ribu-ha-pada-2024-VP3Ic?utm_campaign=read-infinite&utm_medium=infinite&utm_source=internal (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Arafat, B.; Fatchurrohman, N. Innovation in Alternative Material for Craft Business Industry. J. Teknol. 2025, 14, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhendra, H. Limbah Kulit Rotan Ternyata Bisa Gantikan Fiber Glass. Available online: https://ekonomi.bisnis.com/read/20130717/99/151457/limbah-kulit-rotan-ternyata-bisa-gantikan-fiber-glass (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Waluyo, D. Mengembalikan Kejayaan Rotan Indonesia. Available online: https://indonesia.go.id/kategori/editorial/7950/mengembalikan-kejayaan-rotan-indonesia?lang=1 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Satiti, E.R.; Saputra, N.A.; Kalima, T. Chemical Composition and Durability of Rattan Originated Southeast Sulawesi Against Subterranean Termites. J. Trop. Wood Sci. Technol. 2017, 15, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.P.; Nicholas, D.D.; McIntyre, C.R. Recent Patents and Developments in Biocidal Wood Protection Systems for Exterior Applications. Recent. Pat. Mater. Sci. 2010, 1, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoua Essoua, G.G.; Blanchet, P.; Landry, V.; Beauregard, R. Pine Wood Treated with a Citric Acid and Glycerol Mixture: Biomaterial Performance Improved by a Bio-Byproduct. Bioresources 2016, 11, 3049–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkowiak, K.; Emmerich, L.; Simmering, C.; Militz, H. Wood Modification with Citric Acid and Sorbitol-a Review and Future Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Wood Modification (ECWM10), Nancy, France, 25 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, Y.S.; Massijaya, M.Y.; Zaini, L.H.; Abdillah, I.B.; Arsyad, W.O.M. Resistance of Methyl Methacrylate-Impregnated Wood to Subterranean Termite Attack. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarok, M.; Militz, H.; Dumarçay, S.; Gérardin, P. Beech Wood Modification Based on in Situ Esterification with Sorbitol and Citric Acid. Wood Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarok, M.; Militz, H.; Darmawan, I.W.; Hadi, Y.S.; Dumarçay, S.; Gérardin, P. Resistance against Subterranean Termite of Beech Wood Impregnated with Different Derivatives of Glycerol or Polyglycerol and Maleic Anhydride Followed by Thermal Modification: A Field Test Study. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, Y.S.; Herliyana, E.N.; Sulastiningsih, I.M.; Basri, E.; Pari, R.; Abdillah, I.B. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Impregnated Polystyrene Jabon (Anthocephalus cadamba) Glulam. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 891, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarok, M.; Damay, J.; Masson, E.; Fredon, E.; Hadi, Y.S.; Darmawan, I.W.; Gerardin, P. Improvement of Durability of Scots Pine against Termites by Impregnation with Citric Acid and Glycerol Followed by in Situ Polyesterification. In Proceedings of the IRGWP, International Research Group on Wood Protection Meetings 54, Cairns, QLD, Australia, 28 May–1 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.; Mubarok, M. Revolutionizing Wood: Cutting-Edge Modifications, Functional Wood-Based Composites, and Innovative Applications. In Wood Industry—Impacts and Benefits; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Biziks, V.; Bicke, S.; Koch, G.; Militz, H. Effect of phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin oligomer size on the decay resistance of beech wood. Holzforschung 2021, 75, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brelid, P.L.; Simonson, R.; Bergman, Ö.; Nilsson, T. Resistance of acetylated wood to biological degradation. Holz Roh Werkst 2000, 58, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Lopes, L.; Sell, M.; Lopes, R.; Esteves, B. Enhancing Pinus pinaster Wood Durability Through Citric Acid Impregnation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghiyari, H.R.; Bayani, S.; Militz, H.; Papadopoulos, A.N. Heat Treatment of Pine Wood: Possible Effect of Impregnation with Silver Nanosuspension. Forests 2020, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón-Garrido, P.; Oliver-Villanueva, J.V.; Ibiza-Palacios, M.S.; Militz, H.; Mai, C.; Adamopoulos, S. Resistance of wood modified with different technologies against Mediterranean termites (Reticulitermes spp.). Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 82, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.A.S. Wood Modification: An Update. BioResources 2011, 6, 918–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusnierek, K.; Woźnicki, T.; Treu, A. Quality Control of Wood Treated with Citric Acid and Sorbitol Using a Handheld Raman Spectrometer. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, S.; Westin, M.; Schneider, M. Properties of furfurylated wood. Scand. J. For. Res. 2004, 19, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larnøy, E.; Karaca, A.; Gobakken, L.R.; Hill, C.A.S. Polyesterification of wood using sorbitol and citric acid under aqueous conditions. Int. Wood Prod. J. 2018, 9, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Md Tahir, P.; Lum, W.C.; Tan, L.P.; Bawon, P.; Park, B.-D.; Osman Al Edrus, S.S.; Abdullah, U.H. A Review on Citric Acid as Green Modifying Agent and Binder for Wood. Polymers 2020, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkoshi, M.; Kato, A.; Suzuki, K.; Hayashi, N.; Ishihara, M. Characterization of acetylated wood decayed by brown-rot and white-rot fungi. J. Wood Sci. 1999, 45, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgård, A.; Treu, A.; van Zeeland, A.N.T.; Gosselink, R.J.A.; Westin, M. Toxic hazard and chemical analysis of leachates from furfurylated wood. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 1918–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringman, R.; Pilgård, A.; Brischke, C.; Richter, K. Mode of action of brown rot decay resistance in modified wood: A review. Holzforschung 2014, 68, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, D.; Kutnar, A.; Mantanis, G. Wood Modification Technologies—A Review. Iforest–Biogeosciences For. 2017, 10, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, M. Furan Polymer Impregnated Wood. Acetylation of Wood and Boards. AU Patent 2,003,247,294 B2, 12 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarok, M. Valorization of Beech Wood Through Development of Innovative and Environmentally Friendly Chemical Modification Treatments. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gérardin, P. New Alternatives for Wood Preservation Based on Thermal and Chemical Modification of Wood—A Review. Ann. For. Sci. 2016, 73, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, A.; Ganguly, S.; Hom, S.K. Effect of Chemical Modification and Heat Treatment on Biological Durability and Dimensional Stability of Pinus roxburghii Sarg. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 2021, 51, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelier, K.; Thevenon, M.-F.; Petrissans, A.; Dumarcay, S.; Gerardin, P.; Petrissans, M. Control of Wood Thermal Treatment and Its Effects on Decay Resistance: A Review. Ann. For. Sci. 2016, 73, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Råberg, U.; Daniel, G.; Terziev, N. Loss of Strength in Biologically Degraded Thermally Modified Wood. Bioresources 2012, 7, 4658–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, D.; Kutnar, A.; Karlsson, O.; Jones, D. Wood Modification Technologies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781351028226. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinka, S.L.; Altgen, M.; Emmerich, L.; Guigo, N.; Keplinger, T.; Kymäläinen, M.; Thybring, E.E.; Thygesen, L.G. Review of Wood Modification and Wood Functionalization Technologies. Forests 2022, 13, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, L.; Elder, T. Moisture in Untreated, Acetylated, and Furfurylated Norway Spruce Studied During Drying Using Time Domain NMR. Wood Fiber Sci. 2008, 40, 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Altgen, M.; Awais, M.; Altgen, D.; Klüppel, A.; Mäkelä, M.; Rautkari, L. Distribution and Curing Reactions of Melamine–Formaldehyde Resin in Cells of Impregnation-Modified Wood. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejati, P.S.; Imbert, A.; Gérardin-Charbonnier, C.; Dumarçay, S.; Fredon, E.; Masson, E.; Nandika, D.; Priadi, T.; Gérardin, P. Tartaric Acid Catalyzed Furfurylation of Beech Wood. Wood Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, Y.S.; Herliyana, E.N.; Pari, G.; Pari, R.; Abdillah, I.B. Furfurylation Effects on Discoloration and Physical-Mechanical Properties of Wood from Tropical Plantation Forests. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, L.; Militz, H. Study on the impregnation quality of rubberwood (Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) and English oak (Quercus robur L.) sawn veneers after treatment with 1,3-dimethylol-4,5-dihydroxyethyleneurea (DMDHEU). Holzforschung 2020, 74, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieste, A.; Krause, A.; Bollmus, S.; Militz, H. Physical and mechanical properties of plywood produced with 1.3-dimethylol-4.5-dihydroxyethyleneurea (DMDHEU)-modifiedveneers of Betula sp. and Fagus sylvatica. Holz Roh Werkst. 2008, 66, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JIS A 5908-2003; Particleboards. Japanese Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2003.

- Karliati, T.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Dungani, R.; Maulani, R.R.; Hadiyane, A.; Rumidatul, A.; Antov, P.; Savov, V.; Lee, S.H. Performance of Particleboard Made of Agroforestry Residues Bonded with Thermosetting Adhesive Derived from Waste Styrofoam. Polymers 2024, 16, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutiawan, J.; Hadi, Y.S.; Nawawi, D.S.; Abdillah, I.B.; Zulfiana, D.; Lubis, M.A.R.; Nugroho, S.; Astuti, D.; Zhao, Z.; Handayani, M.; et al. The Properties of Particleboard Composites Made from Three Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) Accessions Using Maleic Acid Adhesive. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahfitri, A.; Hermawan, D.; Kusumah, S.S.; Ismadi; Lubis, M.A.R.; Widyaningrum, B.A.; Ismayati, M.; Amanda, P.; Ningrum, R.S.; Sutiawan, J. Conversion of agro-industrial wastes of sorghum bagasse and molasses into lightweight roof tile composite. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024, 14, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syukur, A.; Damanik, A.G.; Mubarok, M.; Hermawan, D.; Sutiawan, J.; Kartikawati, A.; Rahandi Lubis, M.A.; Kusumah, S.S.; Wibowo, E.S.; Narto, N.; et al. Effects of Adhesives on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Chip Block Pallets from Mixed Forest Group Wood Biomass. Bioresources 2025, 20, 3788–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter Associates Laboratory. Application Note Measuring Color Using Hunter L, a, b Versus CIE 1976 L*a*b*; Hunter Associates Laboratory: Reston, VA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, Y.S.; Massijaya, M.Y.; Abdillah, I.B.; Pari, G.; Arsyad, W.O.M. Color Change and Resistance to Subterranean Termite Attack of Mangium (Acacia mangium) and Sengon (Falcataria moluccana) Smoked Wood. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyorini, R.; Umemura, K.; Kusumaningtyas, A.R.; Prayitno, T.A. Effect of Starch Addition on Properties of Citric Acid-Bonded Particleboard Made from Bamboo. Bioresources 2017, 12, 8068–8077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, K.; Ueda, T.; Kawai, S. Effects of Moulding Temperature on the Physical Properties of Wood-Based Moulding Bonded with Citric Acid. For. Prod. J. 2012, 62, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyorini, R.; Umemura, K.; Isnan, R.; Putra, D.R.; Awaludin, A.; Prayitno, T.A. Manufacture and Properties of Citric Acid-Bonded Particleboard Made from Bamboo Materials. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2016, 74, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Wood Protection Association Standard. Standard Method of Evaluating Wood Preservatives by Field Tests with Stakes; American Wood Protection Association Standard: Clermont, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maulana, S.; Wibowo, E.S.; Mardawati, E.; Iswanto, A.H.; Papadopoulos, A.; Lubis, M.A.R. Eco-Friendly and High-Performance Bio-Polyurethane Adhesives from Vegetable Oils: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.A.S. Wood Modification; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780470021729. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, A. Wood Adhesives: Chemistry and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9780203733721. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Fu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Militz, H. Effects of Chemical Modification on the Mechanical Properties of Wood. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2013, 71, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K. A Study of Chemical Structure of Soft and Hardwood and Wood Polymers by FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 71, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanninger, M.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Pereira, H.; Hinterstoisser, B. Effects of Short-Time Vibratory Ball Milling on the Shape of FT-IR Spectra of Wood and Cellulose. Vib. Spectrosc. 2004, 36, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninikas, K.; Mitani, A.; Koutsianitis, D.; Ntalos, G.; Taghiyari, H.R.; Papadopoulos, A.N. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Green Insulation Composites Made from Cannabis and Bark Residues. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hötte, C.; Nopens, M.; Militz, H. Esterification of Wood with Citric Acid and Sorbitol: Effect of the Copolymer on the Properties of the Modified Wood. Part 2: Swelling and Shrinking, Sorption Behaviour and Liquid Water Uptake. Holzforschung 2025, 79, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Meteorology. Climatology and Geo-Physics; Bureau of Meteorology: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Rating | Description |

|---|---|

| 10 | Sound |

| 9.5 | Trace, surface nibbles permitted |

| 9 | Slight attack, up to 3% of cross-sectional area affected |

| 8 | Moderate attack, 3–10% of cross-sectional area affected |

| 7 | Moderate/severe attack and penetration, 10–30% of cross-sectional area affected |

| 6 | Severe attack, 30–50% of cross-sectional area affected |

| 4 | Very severe attack, 50–75% of cross-sectional area affected |

| 0 | Failure |

| Treatment | Resin Content | L* | a* | b* | ∆E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 6% | 65.20 (2.19) | 6.60 (2.19) | 33.40 (3.21) | - |

| 12% | 64.20 (1.64) | 1.64 (8.20) | 8.20 (1.64) | - | |

| Gly-CA-20% | 6% | 41.80 (1.30) | 1.30 (17.2) | 17.20 (1.30) | 26.55 (6.06) |

| 12% | 36.80 (3.78) | 3.78 (17.4) | 17.40 (3.78) | 29.29 (3.75) | |

| Gly-CA-40% | 6% | 23.00 (1.48) | 1.48 (14.2) | 14.20 (1.48) | 46.02 (6.12) |

| 12% | 23.60 (2.07) | 2.07 (14.6) | 14.60 (2.07) | 42.66 (5.43) |

| Sample | TGA: Mass Loss (%) | TGA: Decomposition Range (°C) | TGA: Tmax (°C) | DTG: Peak Temp (°C) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated Rattan Skin (Black line) | −52.30% | 130.2–443.0 | 338.5 | 326.1 | Typical lignocellulosic profile; hemicellulose + cellulose decomposition |

| PB (Untreated Rattan Skin + PU 12%) (Green line) | −51.00% | 106.9–420.3 | 334.5 | 325.1 | PU adhesive increases char, slightly improves stability |

| PB (Gly-CA 20% + PU 12%) (Blue line) | −62.90% | 103.5–487.7 | 353.9 | 349.9 | Crosslinking raises Tmax but reduces char residue |

| PB (Gly-CA 40% + PU 12%) (Red line) | −59.70% | 72.8–559.6 | 356.8 | 351.8 | Highest Tmax, most stable system; secondary peak from modified domains |

| Treatment | Mass Loss (%) | Termite Rating (AWPA E7-07) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated–PU 6% | 49.3 ± 28.7 | 4 | Very severe attack (50–75% of cross-sectional area affected). |

| Untreated–PU 12% | 54.7 ± 25 | 4 | Very severe attack (50–75% area affected). |

| Gly-CA 20%–PU 6% | 71.6 ± 29.2 | 0 | Failure—nearly complete deterioration. |

| Gly-CA 20%–PU 12% | 69.4 ± 35.4 | 0 | Failure—very high degradation. |

| Gly-CA 40%–PU 6% | 43.9 ± 27.9 | 6 | Severe attack (30–50% affected). |

| Gly-CA 40%–PU 12% | 15.3 ± 9.8 | 8 | Moderate attack (3–10% affected). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mubarok, M.; Arifin, B.; Priadi, T.; Hadi, Y.S.; Trisatya, D.R.; Wibowo, E.S.; Abdillah, I.B.; Martha, R.; Syukur, A.; Farobie, O.; et al. Characteristics of Particleboards Made from Esterified Rattan Skin Particles with Glycerol–Citric Acid: Physical, Mechanical, Chemical, and Durability Properties. Polymers 2026, 18, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010107

Mubarok M, Arifin B, Priadi T, Hadi YS, Trisatya DR, Wibowo ES, Abdillah IB, Martha R, Syukur A, Farobie O, et al. Characteristics of Particleboards Made from Esterified Rattan Skin Particles with Glycerol–Citric Acid: Physical, Mechanical, Chemical, and Durability Properties. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleMubarok, Mahdi, Budi Arifin, Trisna Priadi, Yusuf Sudo Hadi, Deazy Rachmi Trisatya, Eko Setio Wibowo, Imam Busyra Abdillah, Resa Martha, Abdus Syukur, Obie Farobie, and et al. 2026. "Characteristics of Particleboards Made from Esterified Rattan Skin Particles with Glycerol–Citric Acid: Physical, Mechanical, Chemical, and Durability Properties" Polymers 18, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010107

APA StyleMubarok, M., Arifin, B., Priadi, T., Hadi, Y. S., Trisatya, D. R., Wibowo, E. S., Abdillah, I. B., Martha, R., Syukur, A., Farobie, O., Zaini, L. H., Kusumah, S. S., Gérardin, P., Militz, H., Zhou, X., Papadopoulou, I. A., & Papadopoulos, A. N. (2026). Characteristics of Particleboards Made from Esterified Rattan Skin Particles with Glycerol–Citric Acid: Physical, Mechanical, Chemical, and Durability Properties. Polymers, 18(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010107