Site-Specific Recruitment, Localization of Ionized Monomer to Macromolecular Crowded Droplet Compartments Can Lead to Catalytic Coacervates for Photo-RAFT in Dilution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

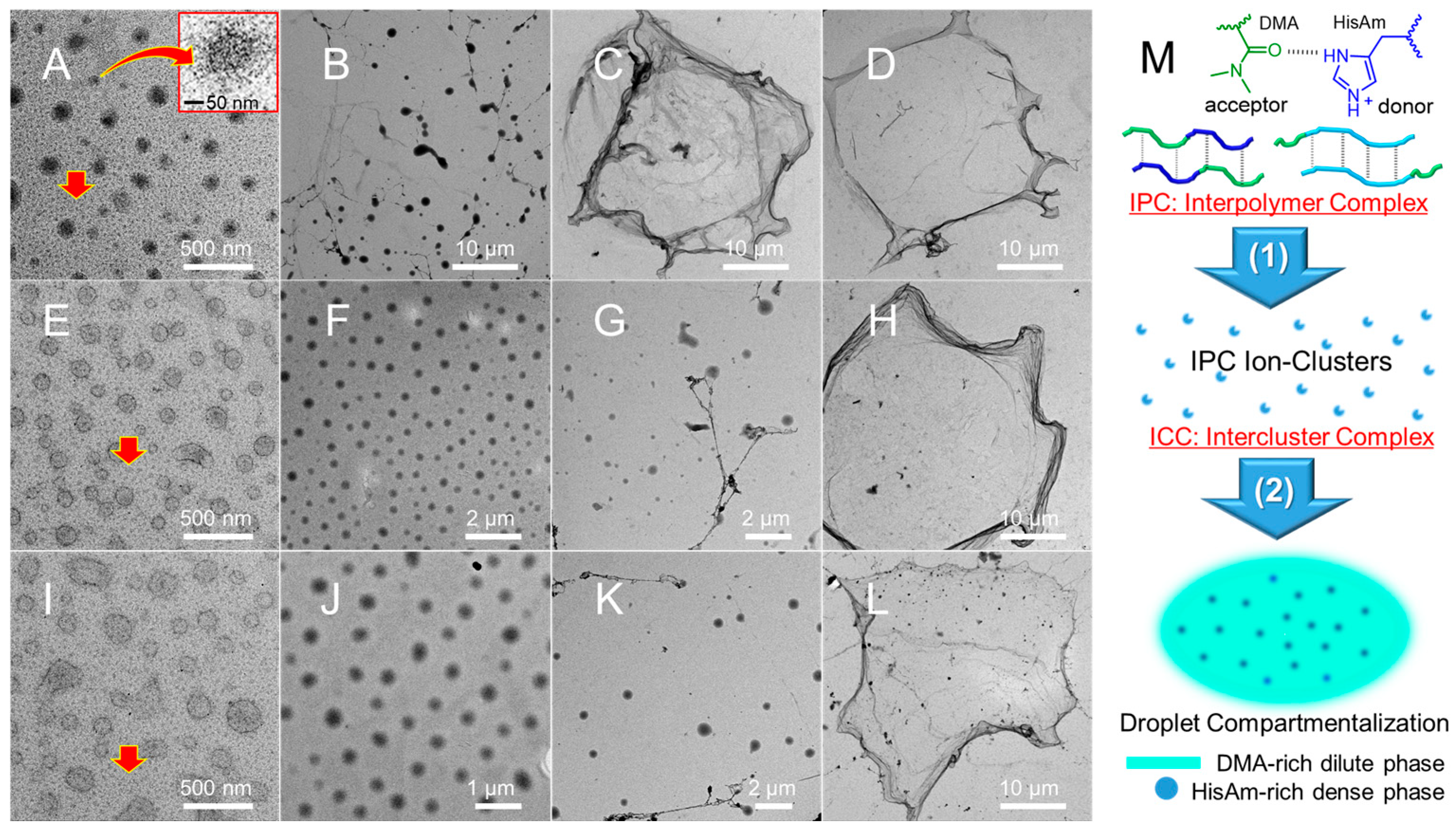

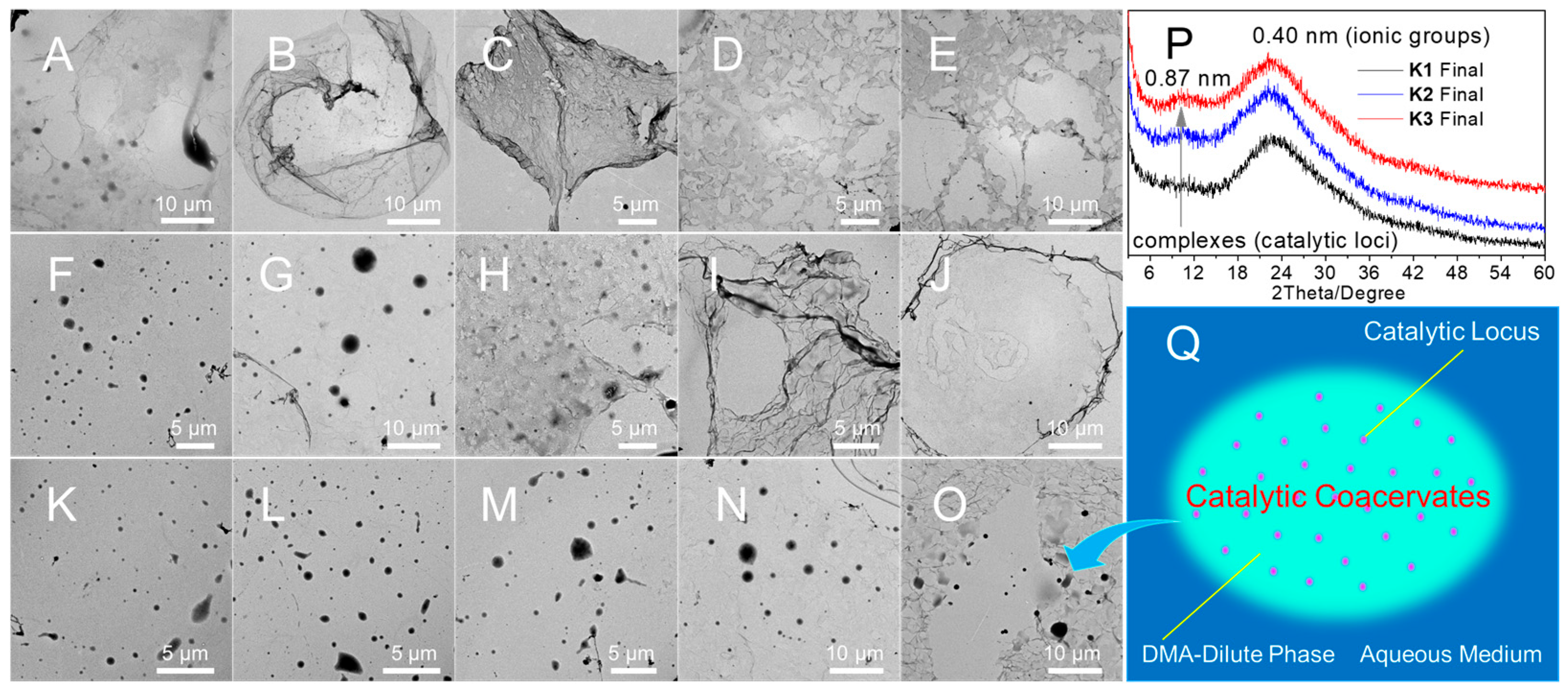

2.1. Spontaneous LLPS Droplet Compartmentalization of Imidazolium-Copolymer in Dilution

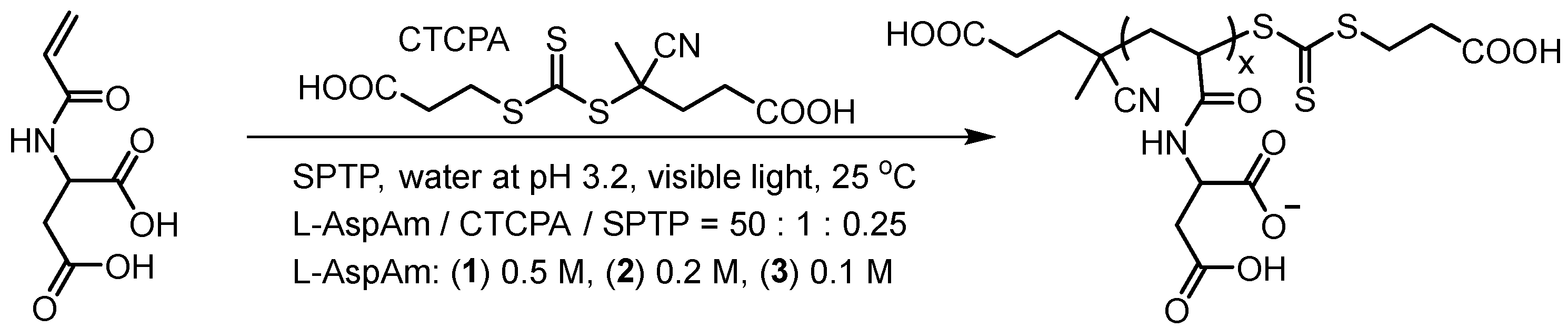

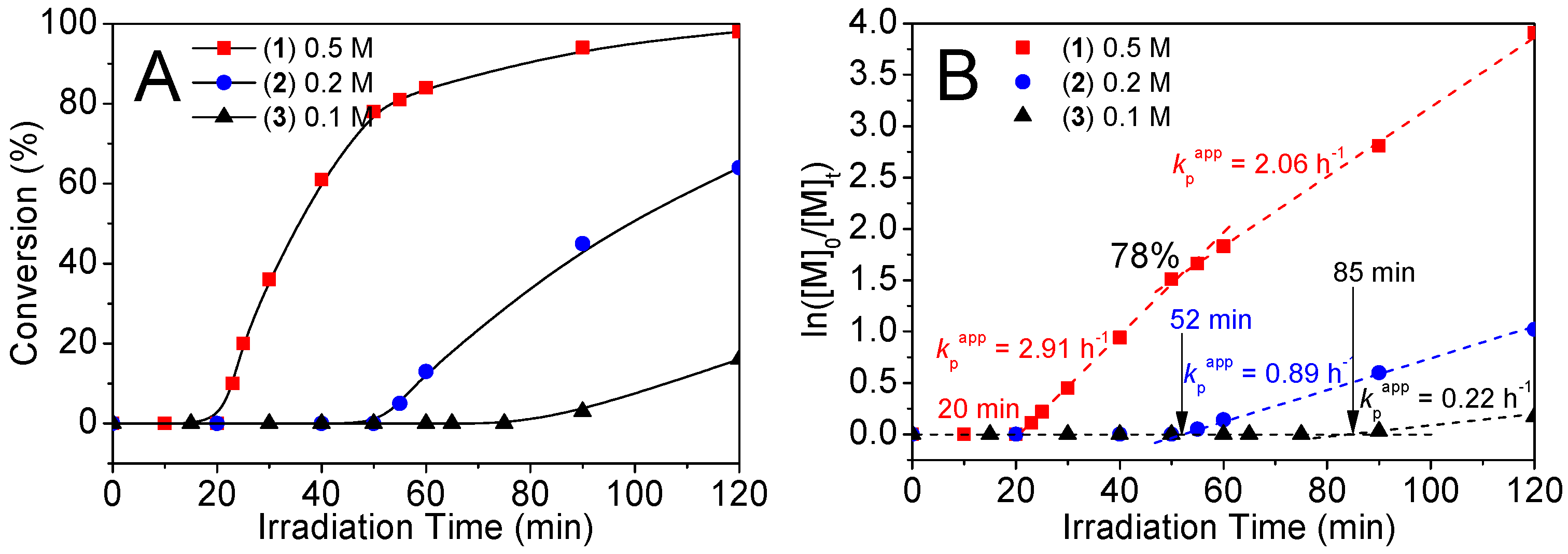

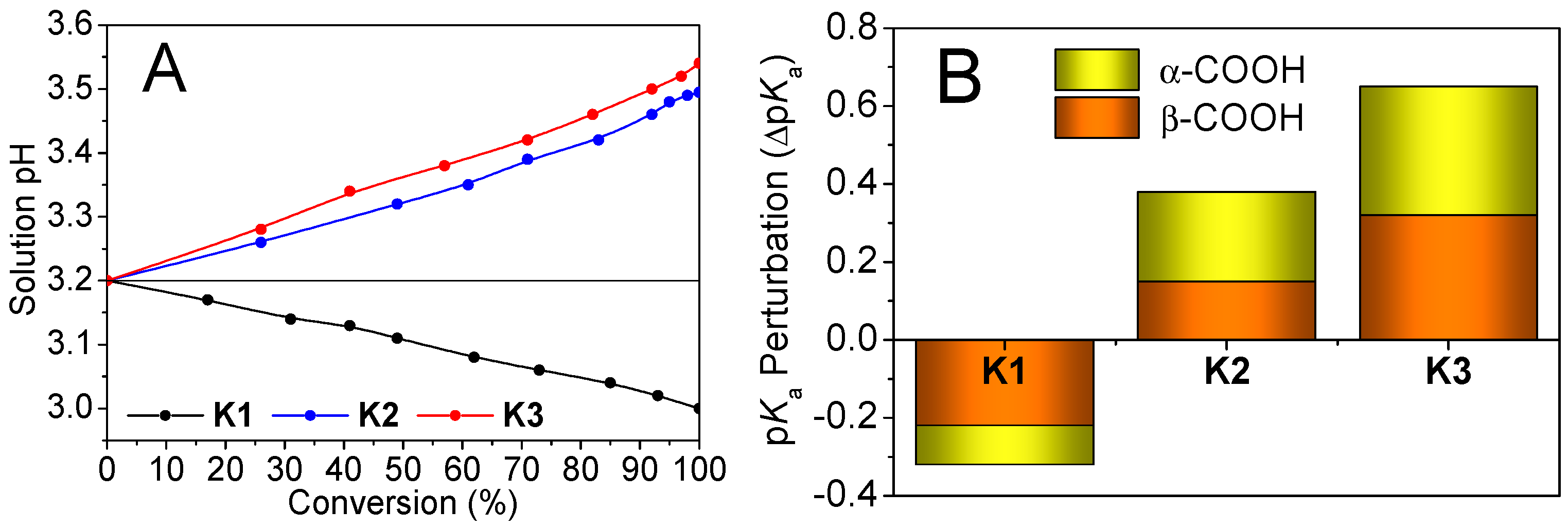

2.2. Site-Specific Monomer Recruitment and Localization into Droplet Compartments

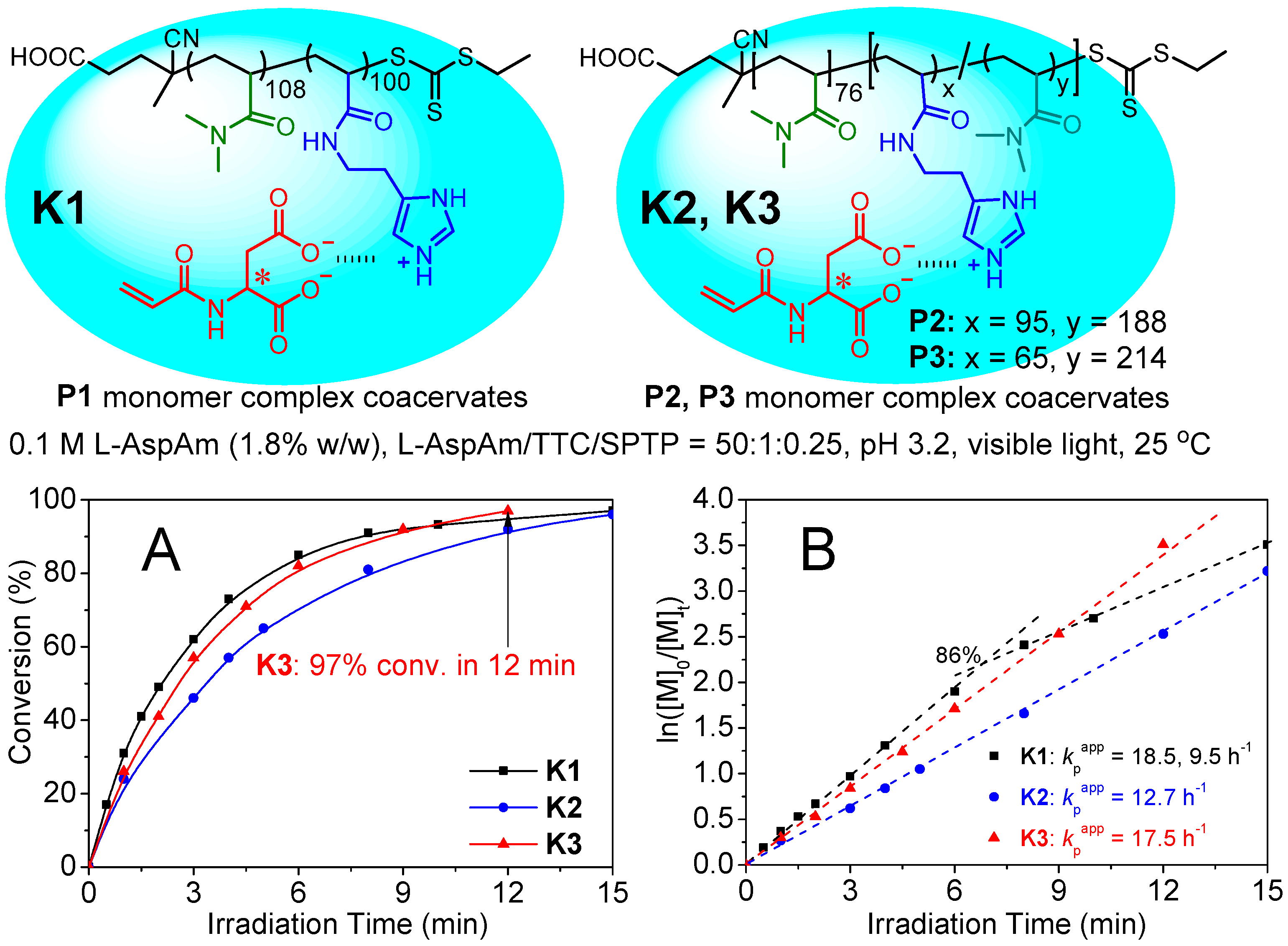

2.3. Kinetic Properties of Catalytic Coacervates for Photo-RAFT in Dilution

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shin, Y.; Brangwynne, C.P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 2017, 357, eaaf4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignon, G.L.; Best, R.B.; Mittal, J. Biomolecular phase separation: From molecular driving forces to macroscopic properties. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2020, 71, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and challenges in studying liquid-liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvanetto, N.; Ivanović, M.T.; Chowdhury, A.; Sottini, A.; Nüesch, M.F.; Nettels, D.; Best, R.B.; Schuler, B. Extreme dynamics in a biomolecular condensate. Nature 2023, 619, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, A.A.; Weber, C.A.; Juelicher, F. Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanopolskyi, A.I.; Mikhnevich, T.A.; Paikar, A.; Nutkovich, B.; Pinkas, I.; Dadosh, T.; Smith, B.S.; Orekhov, N.; Skorb, E.V.; Semenov, S.N. Interplay between autocatalysis and liquid-liquid phase separation produces hierarchical microcompartments. Chem 2023, 9, 3666–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009 (Information for the Public)—The Key to Life at the Atomic Level. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/popular-chemistryprize2009.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Blocher, W.C.; Perry, S.L. Complex coacervate-based materials for biomedicine. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9, e1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Priftis, D.; Farina, R.; Perry, S.L.; Leon, L.; Whitmer, J.; Hoffmann, K.; Tirrell, M.; de Pablo, J.J. Interfacial tension of polyelectrolyte complex coacervate phases. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, A.; Kishimura, A.; Osada, K.; Jang, W.D.; Yamasaki, Y.; Kataoka, K. Semipermeable polymer vesicle (PICsome) self-assembled in aqueous medium from a pair of oppositely charged block copolymers: Physiologically stable micro-/nanocontainers of water-soluble macromolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5988–5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anraku, Y.; Kishimura, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Kataoka, K. Living unimodal growth of polyion complex vesicles via two-dimensional supramolecular polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumiller, W.M., Jr.; Keating, C.D. Phosphorylation-mediated RNA/peptide complex coacervation as a model for intracellular liquid organelles. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokers, I.B.A.; Visser, B.S.; Slootbeek, A.D.; Huck, W.T.S.; Spruijt, E. How droplets can accelerate reactions-coacervate protocells as catalytic microcompartments. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Lipinski, W.P.; Nakashima, K.K.; Huck, W.T.S.; Spruijt, E. A short peptide synthon for liquid-liquid phase separation. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, S. Catalytic coacervate crucibles. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 1028–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Tang, S.C.; Thomas, E.L.; Olsen, B.D. Responsive block copolymer photonics triggered by protein-polyelectrolyte coacervation. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11467–11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoonen, L.; van Hest, J.C. Compartmentalization approaches in soft matter science: From nanoreactor development to organelle mimics. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1109–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donau, C.; Spath, F.; Sosson, M.; Kriebisch, B.A.K.; Schnitter, F.; Tena-Solsona, M.; Kang, H.S.; Salibi, E.; Sattler, M.; Mutschler, H.; et al. Active coacervate droplets as a model for membraneless organelles and protocells. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Cheng, G.; Ho, H.P.; Ho, Y.P.; Yong, K.T. Thermodynamic perspectives on liquid-liquid droplet reactors for biochemical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6555–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Shi, Q.; Tang, W.; Tsung, C.-K.; Hawker, C.J.; Stucky, G.D. Facile RAFT precipitation polymerization for the microwave-assisted synthesis of well-defined, double hydrophilic block copolymers and nanostructured hydrogels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14493–14499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, W.-M.; Hong, C.-Y.; Pan, C.-Y. One-pot synthesis of nanomaterials via RAFT polymerization induced self-assembly and morphology transition. Chem. Commun. 2009, 39, 5883–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanazs, A.; Madsen, J.; Battaglia, G.; Ryan, A.J.; Armes, S.P. Mechanistic insights for block copolymer morphologies: How do worms form vesicles? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16581–16587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, N.; Han, J.; Yu, Q.; Guo, L.; Gao, P.; Lu, X.; Cai, Y. The direct synthesis of interface-decorated reactive block copolymer nanoparticles via polymerisation-induced self-assembly. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 4955–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Sun, H.; Yu, M.; Sumerlin, B.S.; Zhang, L. Photo-PISA: Shedding light on polymerization-induced self-assembly. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 1249–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, J.; Xu, J.; Boyer, C. Polymerization-induced self-assembly using visible light mediated photoinduced electron transfer-reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfold, N.J.W.; Yeow, J.; Boyer, C.; Armes, S.P. Emerging trends in polymerization-induced self-assembly. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 1029–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agosto, F.; Rieger, J.; Lansalot, M. RAFT-mediated polymerization-induced self-assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8368–8392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Lv, X.; An, Z. Modular monomers with tunable solubility: Synthesis of highly incompatible block copolymer nano-objects via RAFT aqueous dispersion polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Cai, M.; Cui, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, L.; Lu, X.; Cai, Y. Synthesis of low-dimensional polyion complex nanomaterials via polymerization-induced electrostatic self-assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1053–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos, I.; Terenzi, C.; Sprakel, J. Chemical feedback in templated reaction-assembly networks. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 10675–10685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Magana, J.R.; Sobotta, F.; Wang, J.; Stuart, M.A.C.; Van Ravensteijn, B.G.P.; Voets, I.K. Switchable electrostatically templated polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202206780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobotta, F.H.; van Ravensteijn, B.G.P.; Voets, I.K. Sequence-controlled neutral-ionic multiblock-like copolymers through switchable PIESA in a one-pot approach. ACS Macro Lett. 2025, 14, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Zhao, Q.Q.; Wang, L.; Huang, L.L.; Liu, O.Z.; Lu, X.H.; Cai, Y.L. Polymerization-induced self-assembly promoted by liquid-liquid phase separation. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Fan, X.; Xu, X.; Niu, W.; Cai, Y. Self-adaptable activation and inactivation of RAFT polymerization: A liquid-liquid phase separation scaffold-client platform. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 239, 114306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.G.; Fletcher, S.P. From autocatalysis to survival of the fittest in self-reproducing lipid systems. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.X.; Rivas, G.N.; Minton, A.P. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: Biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 37, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guin, D.; Gruebele, M. Weak chemical interactions that drive protein evolution: Crowding, sticking, and quinary structure in folding and function. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10691–10717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanya, A.R.; Boyd-Shiwarski, C.R. Molecular crowding: Physiologic sensing and control. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2024, 86, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.F.; Lutzki, J.; Dalgliesh, R.; Prévost, S.; Gradzielski, M. pH-Responsive rheology and structure of poly(ethylene oxide)–poly(methacrylic acid) interpolymer complexes. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylaeva, S.; Brehm, M.; Sebastiani, D. Salt bridge in aqueous solution: Strong structural motifs but weak enthalpic effect. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosshard, H.R.; Marti, D.N.; Jelesarov, I. Protein stabilization by salt bridges: Concepts, experimental approaches and clarification of some misunderstandings. J. Mol. Recognit. 2004, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Y.; Hefter, G. Ion pairing. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4585–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.E.; Kulp, D.W.; DeGrado, W.F. Salt bridges: Geometrically specific, designable interactions. Proteins 2011, 79, 898–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddingh, B.C.; van Hest, J.C.M. Artificial cells: Syntheticcompartments with life-like functionality and adaptivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, G.; Gao, H.; Lu, L.; Cai, Y. Effect of mild visible light on rapid aqueous RAFT polymerization of water-soluble acrylic monomers at ambient temperature: Initiation and activation. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 3917–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Q.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y. Electrostatic manipulation of triblock terpolymer nanofilm compartmentalization during aqueous photoinitiated polymerization-induced self-assembly. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 2220–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, P.; Joshi, A.; Majumdar, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Intermolecular charge-transfer modulates liquid-liquid phase separation and liquid-to-solid maturation of an intrinsically disordered pH-responsive domain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 20380–20389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, E.; Abe, K. Interactions between macromolecules in solution and intermacromolecular complexes. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1982, 45, 1–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanawongwiboon, T.; Ghaffarlou, M.; Sütekin, S.D.; Pasanphan, W.; Güven, O. Preparation of multifunctional poly(acrylic acid)-poly(ethylene oxide) nanogels from their interpolymer complexes by radiation-induced intramolecular crosslinking. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkeeva, Z.S.; Mun, G.A.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Bitekenova, A.B.; Dubolazov, A.V.; Esirkegenova, S.Z. pH effects in the formation of interpolymer complexes between poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) and poly(acrylic acid) in aqueous solutions. Euro. Phys. J. E 2003, 10, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nott, T.J.; Petsalaki, E.; Farber, P.; Jervis, D.; Fussner, E.; Plochowietz, A.; Craggs, T.D.; Bazett-Jones, D.P.; Pawson, T.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; et al. Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles. Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.E.; Becktel, W.J.; Dahlquist, F.W. pH-induced denaturation of proteins–A single salt bridge constitutes 3-5 kcal/mol to the free-energy of folding of T4-lysozyme. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 2403–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.N.; Grimsley, G.R.; Scholtz, J.M. Protein ionizable groups: pK values and their contribution to protein stability and solubility. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 13285–13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmadottir, T.; Malmendal, A.; Leiding, T.; Lund, M.; Linse, S. Charge regulation during amyloid formation of alpha-synuclein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7777–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Hamad, N.; Akintola, J.; Schlenoff, J.B. Quantifying hydrophilicity in polyelectrolytes and polyzwitterions. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 3422–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez Marrero, I.A.; Kaiser, N.; von Vacano, B.; Konradi, R.; Crosby, A.J.; Perry, S.L. Brittle-to-ductile transitions of polyelectrolyte complexes: Humidity, temperature, and salt. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 2925–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moad, G.; Rizzardo, E.; Thang, S.H. Toward living radical polymerization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.I.; Eades, C.B.; Vratsanos, M.A.; Gianneschi, N.C.; Sumerlin, B.S. Ultrafast xanthate-mediated photoiniferter polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202309951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.L.; He, Z.Y.; Zhou, Y.C.; Kou, T.T.; Gong, K.L.; Nan, F.C.; Bezuneh, T.T.; Han, S.G.; Boyer, C.; Yu, W.W. Design of an ultrafast and controlled visible light-mediated photoiniferter RAFT polymerization for polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202422975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.; Yin, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y. Ultrafast monomer emulsified aqueous ring-opening metathesis polymerization for the synthesis of water-soluble polynorbornenes with precise structure. ACS Macro Lett. 2023, 12, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Kong, W.; An, Z. Enzyme catalysis for reversible deactivation radical polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202202033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.D.; An, Z.S. Amplified cascade catalysis for RAFT polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202421851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.Y.; Zhang, S.D.; Tang, X.H.; Qiao, G.G.; Armes, S.P.; An, Z.S. Near-infrared photoenzymatic catalysis at ppb levels enables ultrahigh-molecular-weight polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 33153–33161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, S.H.; Chong, Y.K.; Mayadunne, R.T.A.; Moad, G.; Rizzardo, E. A novel synthesis of functional dithioesters, Dithiocarbamates, xanthates and trithiocarbonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 2435–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, J.; Lu, X.; Cai, Y. Like-charge PISA: Polymerization-induced like-charge electrostatic self-assembly. ACS Macro Lett. 2023, 12, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstert, B.; Henne, A.; Hesse, A.; Jacobi, M.; Wallbillich, G. Acylphosphine Compounds and their Use as Photoinitiators. U.S. Patent 4719297, 12 January 1988. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niu, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Cai, Y. Site-Specific Recruitment, Localization of Ionized Monomer to Macromolecular Crowded Droplet Compartments Can Lead to Catalytic Coacervates for Photo-RAFT in Dilution. Polymers 2026, 18, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010106

Niu W, Wang X, Zhang R, Cai Y. Site-Specific Recruitment, Localization of Ionized Monomer to Macromolecular Crowded Droplet Compartments Can Lead to Catalytic Coacervates for Photo-RAFT in Dilution. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Wenjing, Xiyu Wang, Ran Zhang, and Yuanli Cai. 2026. "Site-Specific Recruitment, Localization of Ionized Monomer to Macromolecular Crowded Droplet Compartments Can Lead to Catalytic Coacervates for Photo-RAFT in Dilution" Polymers 18, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010106

APA StyleNiu, W., Wang, X., Zhang, R., & Cai, Y. (2026). Site-Specific Recruitment, Localization of Ionized Monomer to Macromolecular Crowded Droplet Compartments Can Lead to Catalytic Coacervates for Photo-RAFT in Dilution. Polymers, 18(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010106