Combined Use of Vibrational Spectroscopy, Ultrasonic Echography, and Numerical Simulations for the Non-Destructive Evaluation of 3D-Printed Materials for Defense Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Thermal Protocols

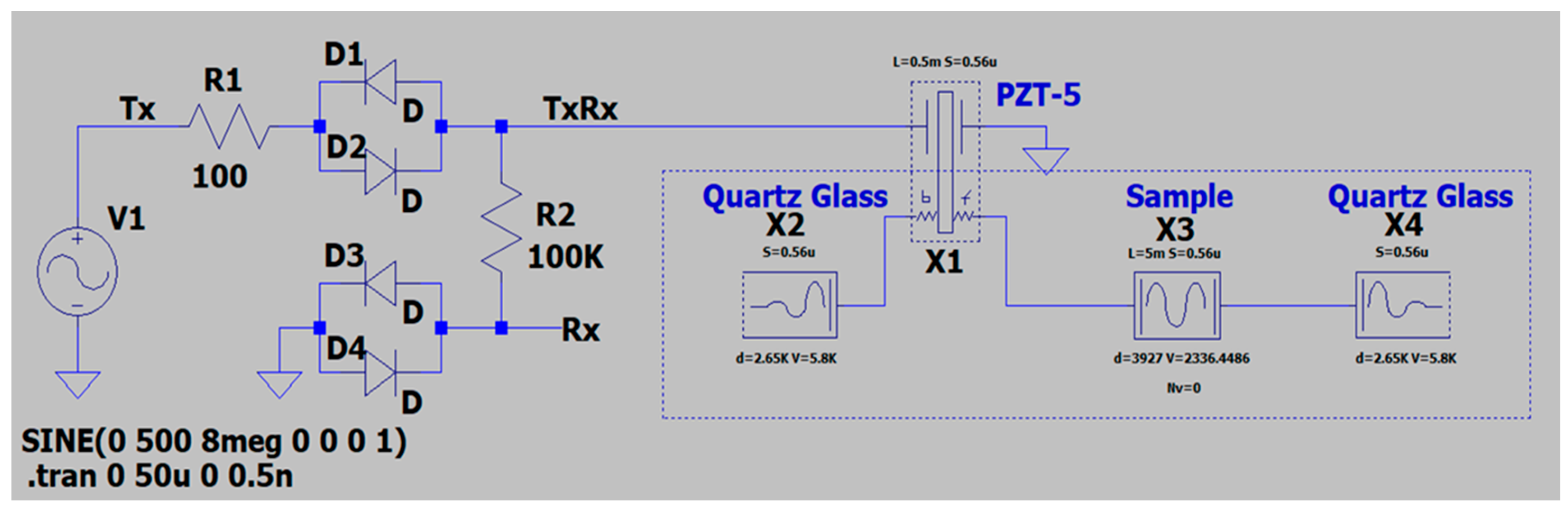

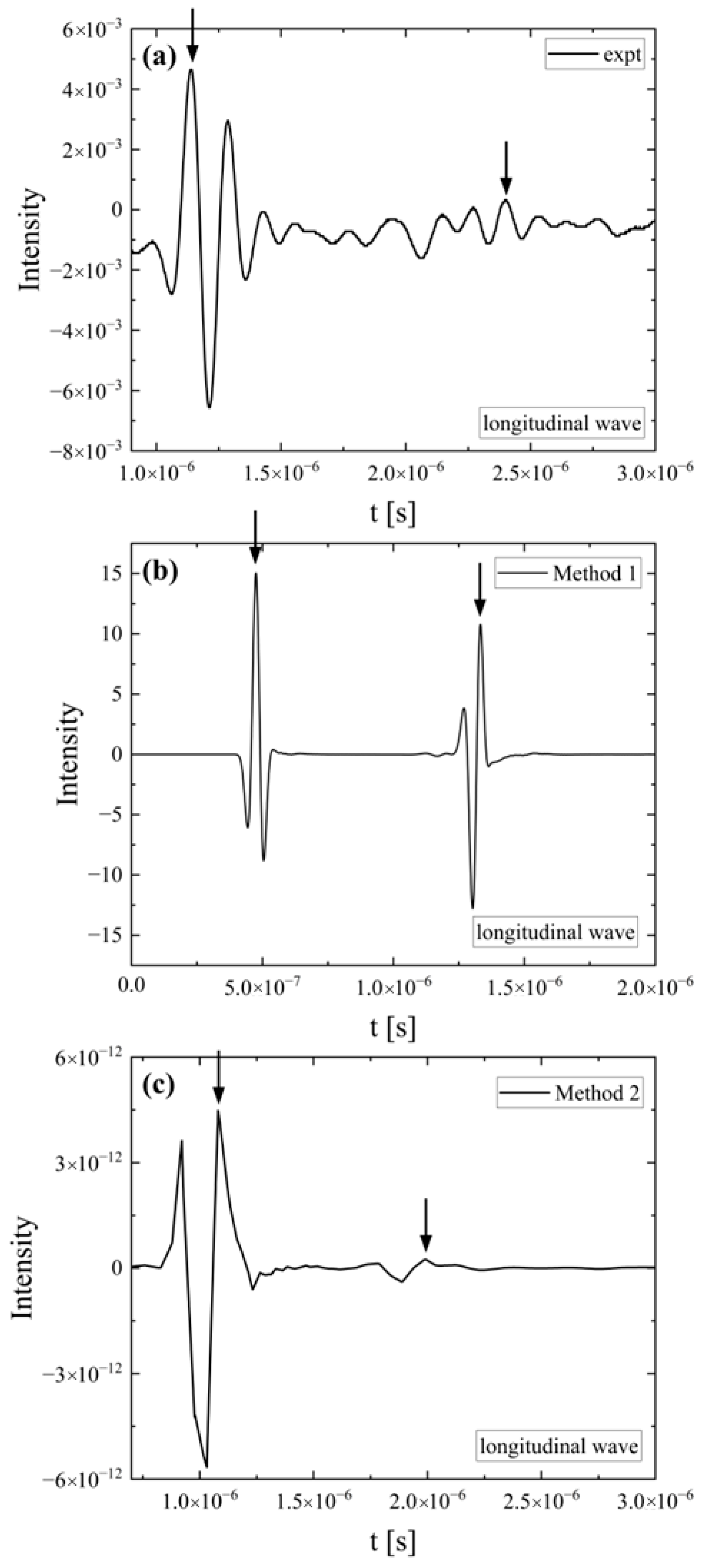

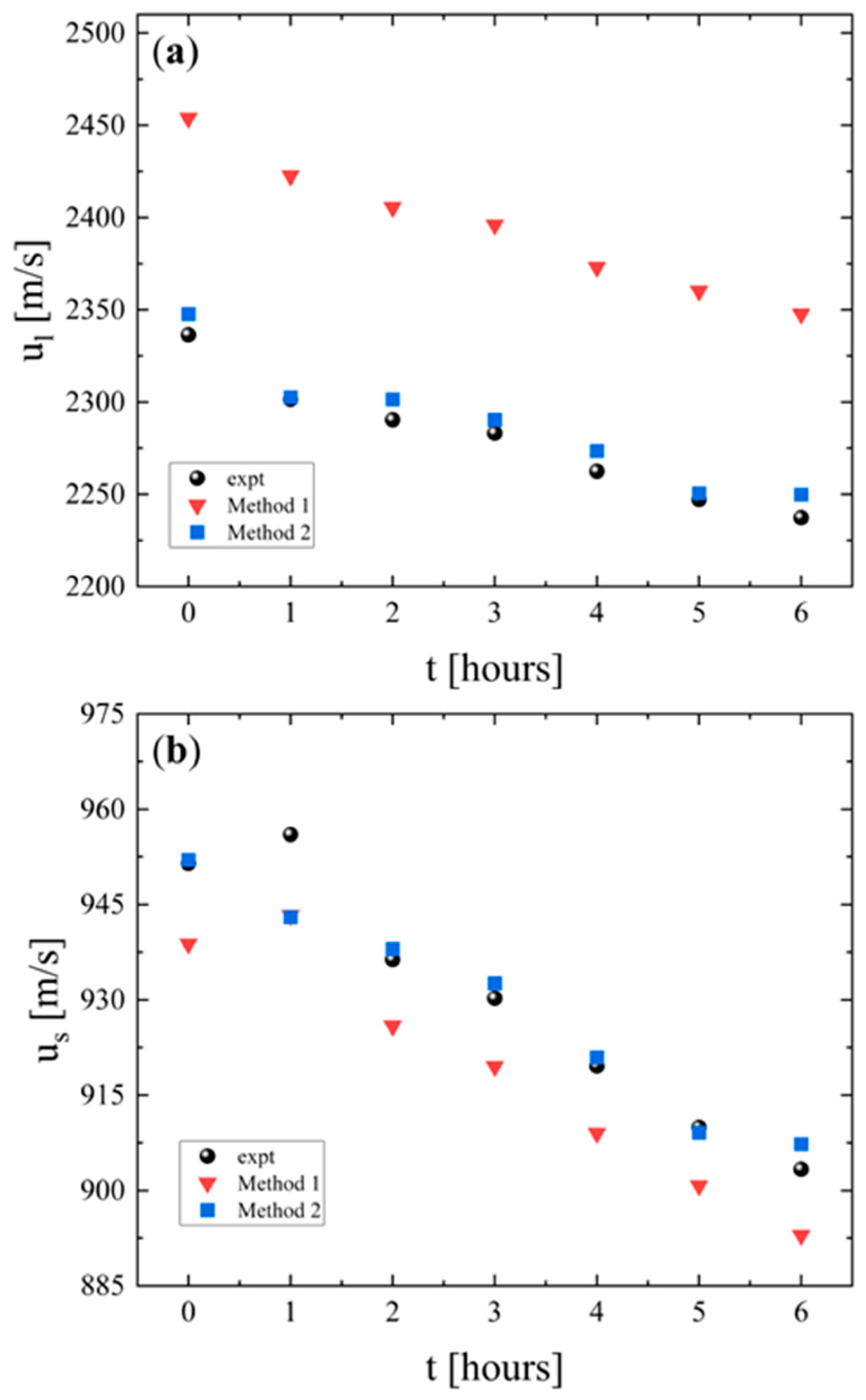

2.2. Ultrasonic Echography–Velocity Measurements

2.3. Vibrational Spectroscopy

2.4. Simulation Methods

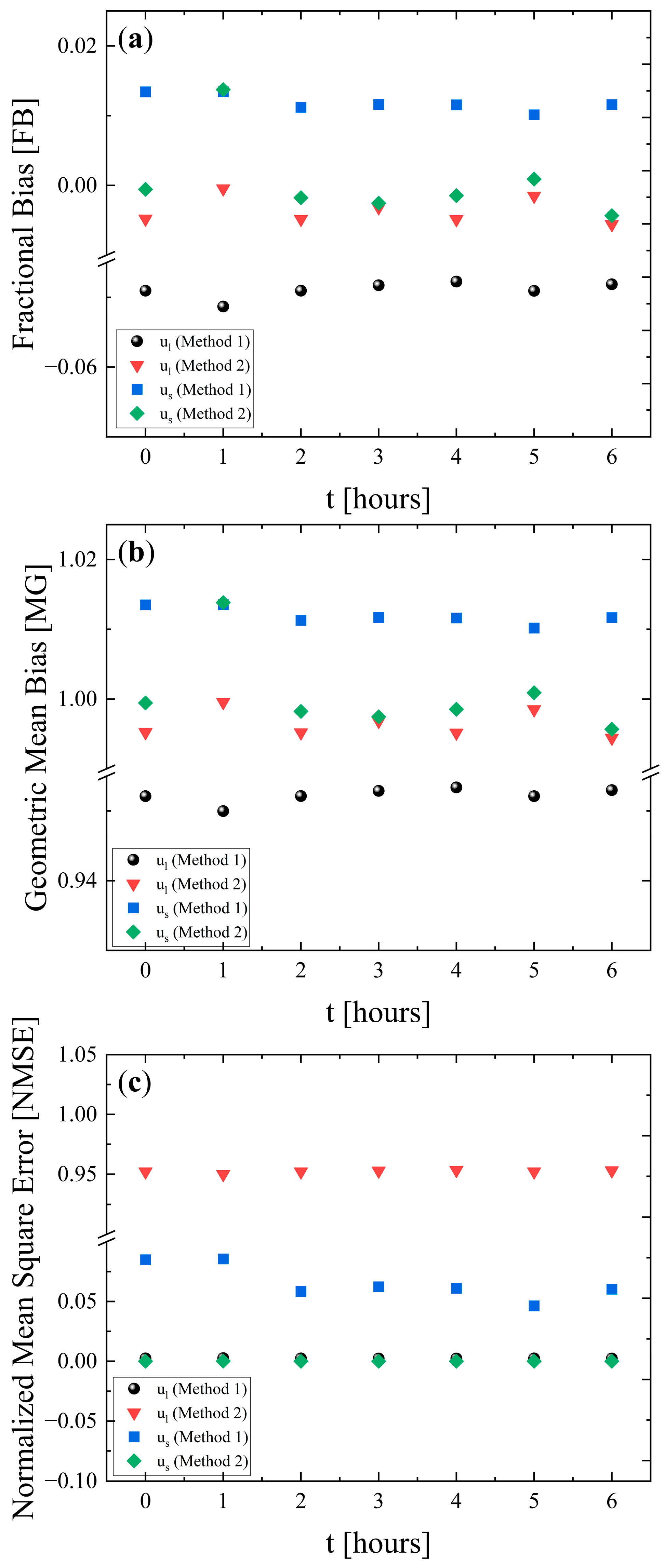

2.5. Evaluation of the Elastic Properties

3. Results and Discussion

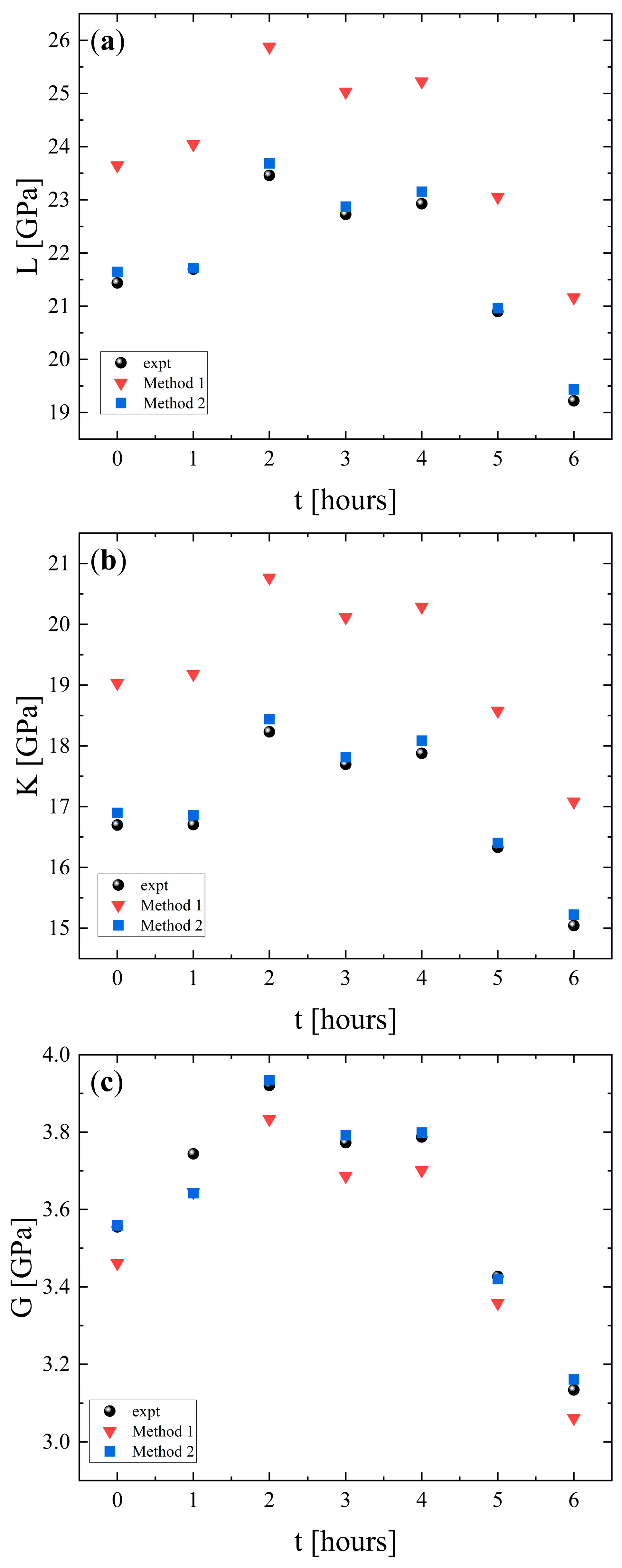

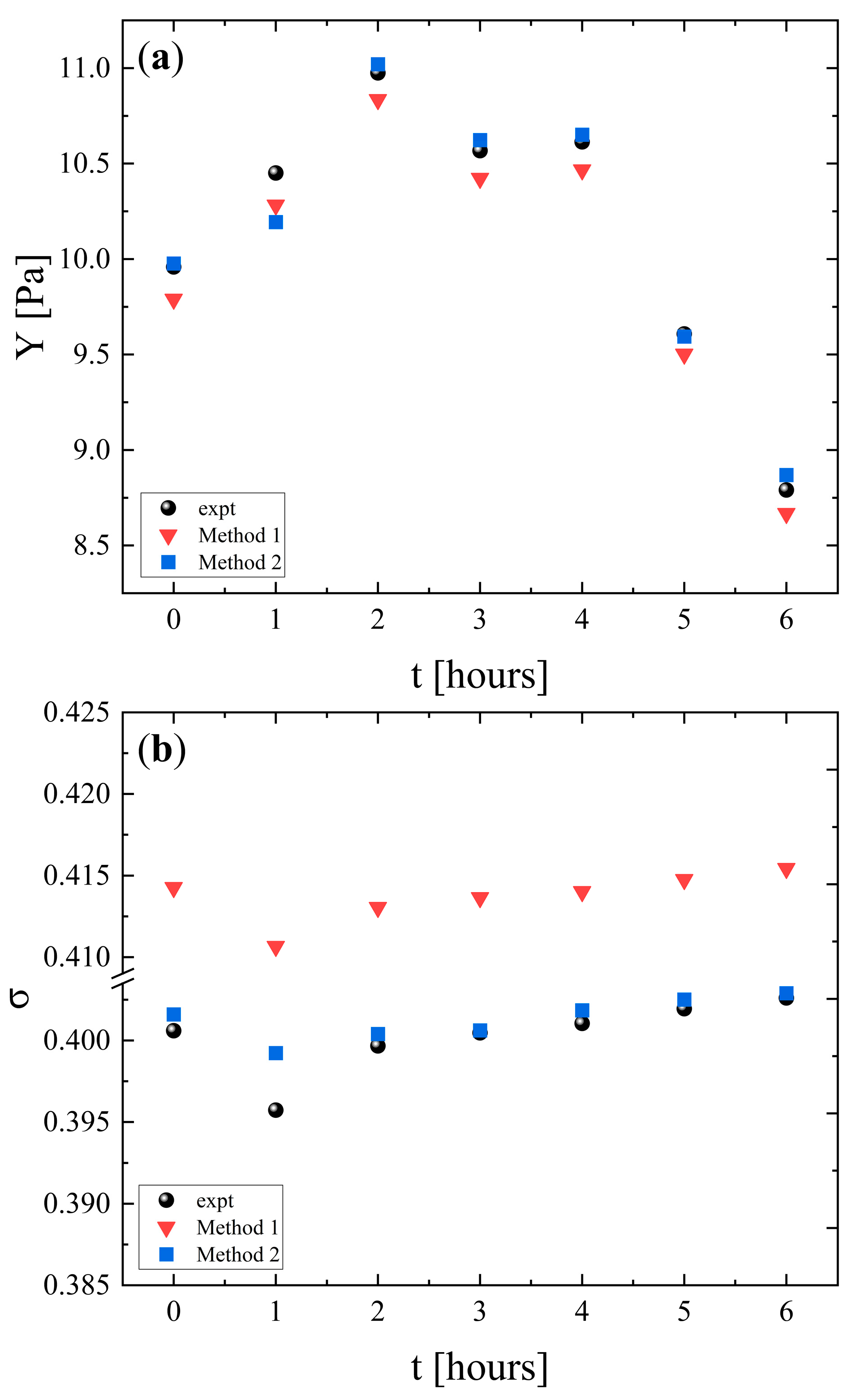

3.1. Ultrasonic Echography and Elastic Properties

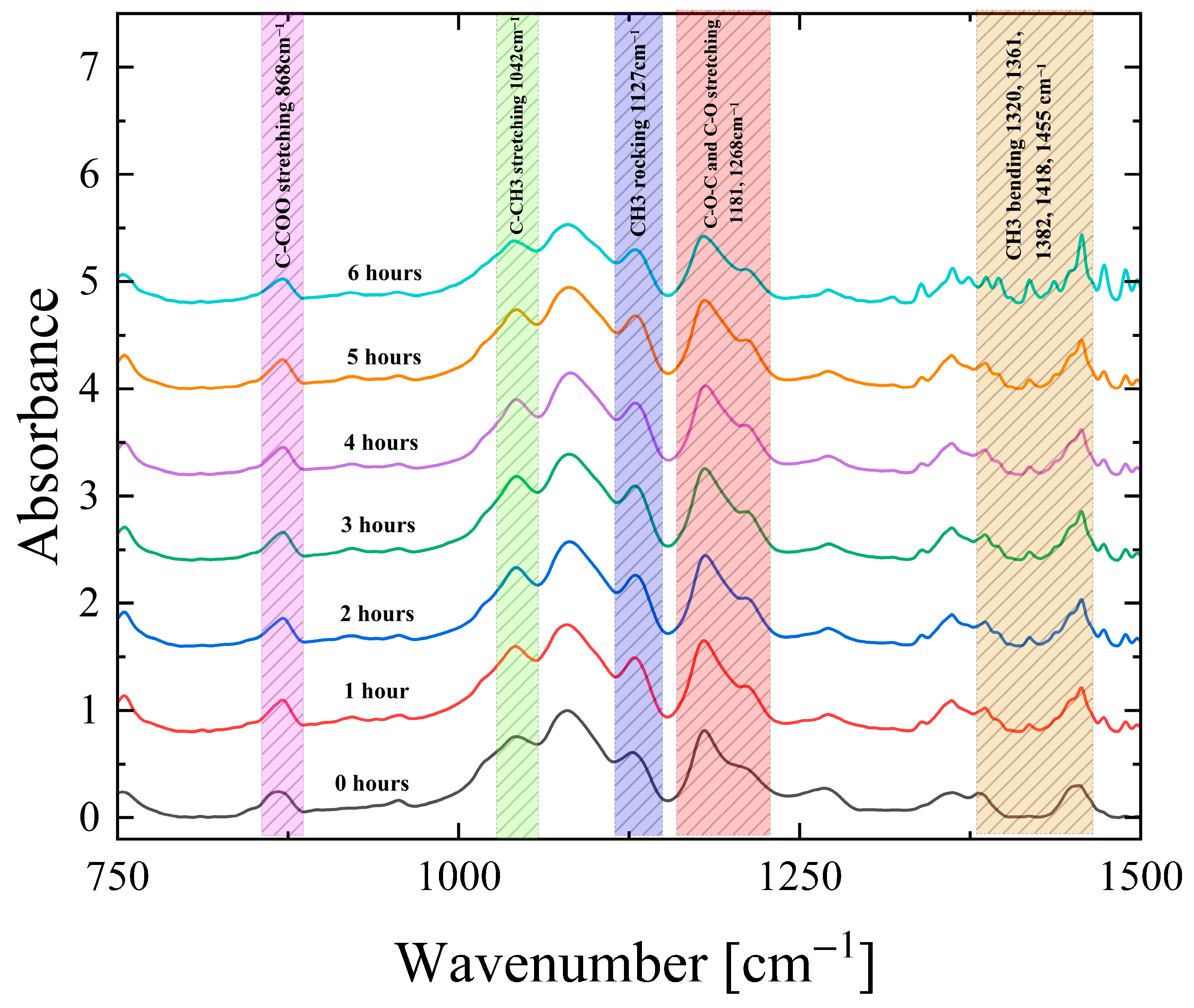

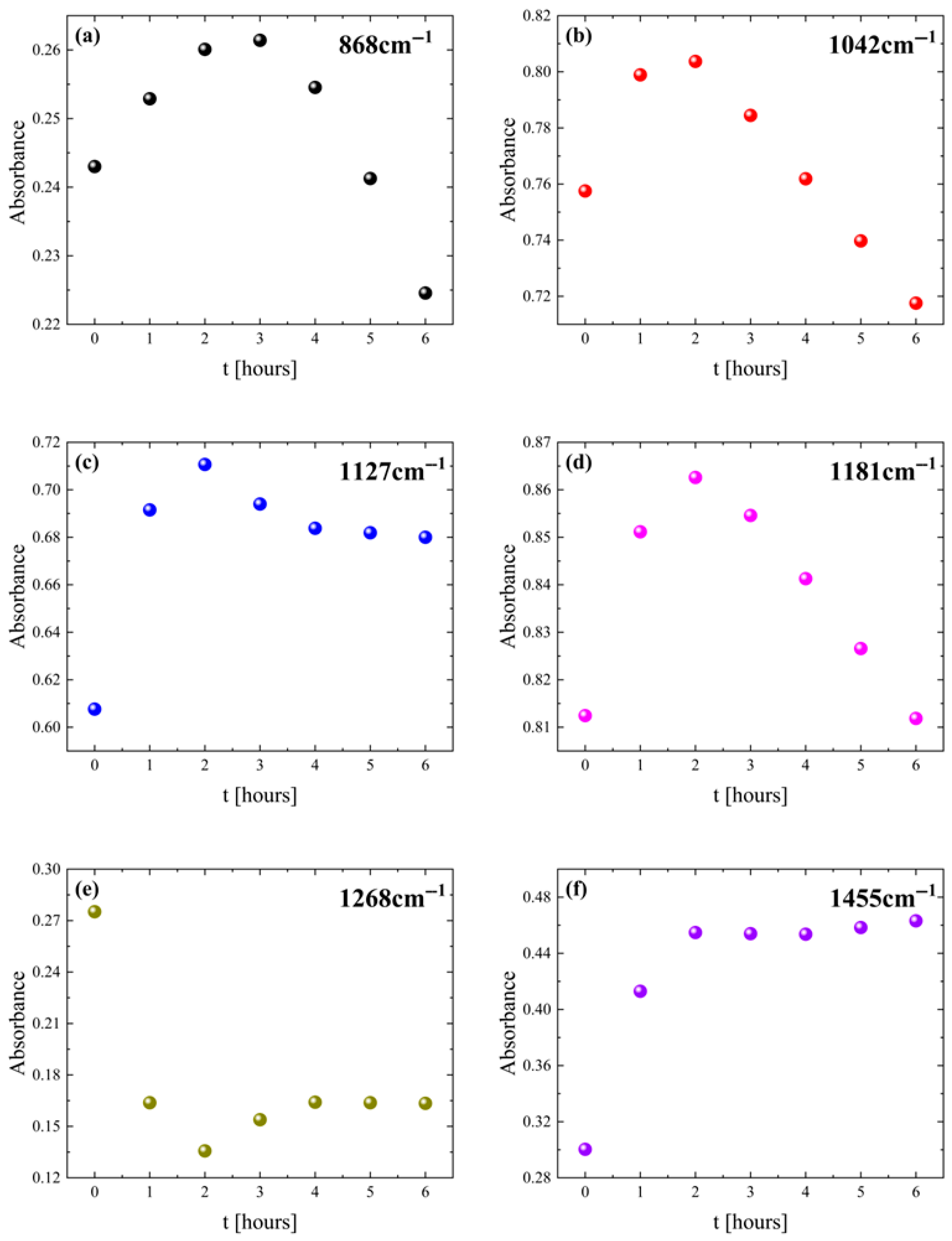

3.2. Vibrational Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, O.; Avérous, L. Poly (lactic acid): Plasticization and properties of biodegradable multiphase systems. Polymer 2001, 42, 6209–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, H.; Ikada, Y. Properties and morphologies of poly(l-lactide): 1. Annealing condition effects on properties and morphologies of poly(l-lactide). Polymer 1995, 36, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, F.; Kaptan, A. Effects of annealing temperature and duration on mechanical properties of PLA plastics produced by 3D Printing. Eur. Mech. Sci. 2023, 7, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Duarte, M.E.; Vega-Rios, A. Comprehensive Analysis of Rheological, Mechanical, and Thermal Properties in Poly(lactic acid)/Oxidized Graphite Composites: Exploring the Effect of Heat Treatment on Elastic Modulus. Polymers 2024, 16, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, T.M.; Kallingal, A.; Suresh, A.M.; Mahapatra, D.K.; Hasanin, M.S.; Haponiuk, J.; Thomas, S. 3D printing of polylactic acid: Recent advances and opportunities. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhad, M.S.; Abu-Jdayil, B.; Mourad, A.H.I.; Iqbal, M.Z. Thermal Insulation and Mechanical Properties of Polylactic Acid (PLA) at Different Processing Conditions. Polymers 2020, 12, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafarika, P.; Mouzakis, D.E.; Nasikas, N.; Kalampounias, A.G. Thermal degradation of 3D printing processed polylactide samples by means of vibrational spectroscopy. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, K.T.; Fanta, G.M.; Tilinti, B.Z.; Regasa, M.B. Polylactic Acid Based Biocomposite for 3D Printing: A Review. Compos. Mater. 2024, 82, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, M. 3D Printing in Military Applications: FDM Technology, Materials, and Implications. Adv. Mil. Technol. 2023, 182, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natayu, A.; Muhammad, A.A.; Tumad, A.; Saptaji, K.; Trisnadewi, I.A.N.T.; Triawan, F.; Ramadhan, A.I.; Azhari, A. Effect of Annealing on the Mechanical Properties of Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printed PLA. J. Rekayasa Mesin 2024, 15, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojković, J.R.; Turudija, R.; Vitković, N.; Górski, F.; Păcurar, A.; Pleşa, A.; Ianoşi-Andreeva-Dimitrova, A.; Păcurar, R. An Experimental Study on the Impact of Layer Height and Annealing Parameters on the Tensile Strength and Dimensional Accuracy of FDM 3D Printed Parts. Materials 2023, 16, 4574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Panes, A.; Claver, J.; Camacho, A.M. The Influence of Manufacturing Parameters on the Mechanical Behaviour of PLA and ABS Pieces Manufactured by FDM A Comparative Analysis. Materials 2018, 11, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunt, J. Large-scale production, properties and commercial applications of polylactic acid polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1998, 591, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wach, R.A.; Wolszczak, P.; Adamus-Wlodarczyk, A. Enhancement of mechanical properties of FDM PLA parts via thermal annealing. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2018, 303, 1800169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanth, N.; Jaswanthraj, K.; Sandeep, S.; Mallaya, N.H.; Siddharth, S.R. Effect of heat treatment on mechanical properties of 3D printed PLA. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 123, 104764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhamannil, R.V.; Govindan, P.; Edacherian, A.; Hadidi, H.M. Impact of process parameters and heat treatment on fused filament fabricated PLA and PLA-CF. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2024, 184, 2199–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, T.; Todo, M.; Tsuji, H. Effect of annealing on the mechanical properties of PLA/PCL and PLA/PCL/LTI polymer blends. J. Mech. Behav. 2011, 43, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tábi, T.; Sajó, I.; Szabo, F.; Luyt, A.S.; Kovacs, J.G. Crystalline structure of annealed polylactic acid and its relation to processing. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2010, 4, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidlou, S.; Huneault, M.A.; Li, H.; Park, C.B. Poly(lactic acid) crystallization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1657–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, H.; Xie, F.; Chen, L.; Li, X. Effect of annealing and orientation on microstructures and mechanical properties of polylactic acid. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2008, 48, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, H.; Tiwary, P.; Colwell, J.E.; Kontopoulou, M. Improvements in the crystallinity and mechanical properties of PLA by nucleation and annealing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 166, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohotti, D.; Weerasinghe, D.; Bogahawaththa, M.; Wang, H.; Wijesooriya, K.; Hazell, P.J. Quasi-static and dynamic compressive behaviour of additively manufactured Menger fractal cube structures. Def. Technol. 2024, 37, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, D.A.; Akay, B.D. Fabrication and characterization of carbon and glass fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites by fused filament fabrication. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeman, D.; Subramaniyan, M.K.; Vellaisamy, M.; Kannan, S. Fabrication of structurally graded material (pure PLA/WFPC): Mechanical and microscopic aspects. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E 2023, 239, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A.F.; Rajasekhar, A.; Rajendra, R. Numerical Simulations on Hexa-copter Drone for I-Section and Hollow Square Arm Cross-Sections for PLA-CF and CFRP Materials. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 12, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, A.; Ribeiro, S.; Grossiord, C.; Alves, A.; Vestberg, R.H.; Salles, V.; Brunon, C.; Gritsch, K.; Grosgogeat, B.; Bayon, Y. FTIR microscopy contribution for comprehension of degradation mechanisms in PLA-based implantable medical devices. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017, 28, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.E.; Meza, J.M.; Buiochi, F. Measurement of elastic properties of materials by the ultrasonic through-transmission technique. DYNA 2011, 78, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ciecieląg, K.; Kęcik, K.; Skoczylas, A.; Matuszak, J.; Korzec, I.; Zaleski, R. Non-destructive detection of real defects in polymer composites by ultrasonic testing and recurrence analysis. Materials 2022, 15, 7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Lopez-Anido, R.A.; Gardner, D.J. Enhancing the interlayer tensile strength of 3D printed short carbon fiber reinforced PETG and PLA composites via annealing. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Guo, X.; He, Z.; Liang, X.; Wang, M.; Jin, G. Thermal degradation kinetics study of molten polylactide based on Raman spectroscopy. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 61, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogiannidis, G.; Tsigoias, S.; Kalampounias, A.G. Conformational energy barriers in methyl acetate- ethanol solutions: A temperature-dependent ultrasonic relaxation study and molecular orbital calculations. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 302, 112519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafarika, P.; Nasikas, N.; Kalampounias, A.G. How Ultrasonic Pulse-Echo Techniques and Numerical Simulations Can Work Together in the Evaluation of the Elastic Properties of Glasses. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, R. Digital computer simulation of a piezoelectric thickness vibrator. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1977, 62, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, C.G.; Morris, S.A. A three-port model for thickness mode transducers using SPICE II. In Proceedings of the IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, Dallas, TX, USA, 14–16 November 1984; pp. 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, W.M., Jr. Controlled-source analogous circuits and SPICE models for piezoelectric transducers. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 1984, 41, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P. Solid State Physics: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Wang, Y.; Ooka, R.; Flageul, C.; Kim, Y.; Kikumoto, H.; Wang, Z.; Sartelet, K. Modeling of street-scale pollutant dispersion by coupled simulation of chemical reaction, aerosol dynamics, and CFD. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 1421–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trini Castelli, S.; Armand, P.; Tinarelli, G.; Duchenne, C.; Nibart, M. Validation of a Lagrangian particle dispersion model with wind tunnel and field experiments in urban environment. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 193, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.C.; Hanna, S.R. Air Quality Model Performance Evaluation. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2004, 87, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.R.; Hansen, O.R.; Dharmavaram, S. FLACS CFD air quality model performance evaluation with Kit Fox, MUST, Prairie Grass, and EMU observations. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 4675–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Insyani, R.; Prasetyo, D.; Prajitno, H.; Sitompul, J. Molecular Weight and Structural Properties of Biodegradable PLA Synthesized with Different Catalysts by Direct Melt Polycondensation. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2015, 47, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, B.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W.; Hussein, M.Z. Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(ethylene glycol) Polymer Nanocomposites: Effects of Graphene Nanoplatelets. Polymers 2014, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.; Cran, M.J.; Nerín, C.; Bigger, S.W. Development and characterization of HPMC films containing PLA nanoparticles loaded with green tea extract for food packaging applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 156, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giełdowska, M.; Puchalski, M.; Sztajnowski, S.; Krucińska, I. Evolution of the Molecular and Supramolecular Structures of PLA during the Thermally Supported Hydrolytic Degradation of Wat Spinning Fibers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 10100–10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, K.; Shao, C.; Li, Q.; Shen, C. Unusual structural evolution of poly(lactic acid) upon annealing in the presence of an initially oriented mesophase. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonés, A.; Peponi, L.; Lieblich, M.; Benavente, R.; Fiori, S. In Vitro Degradation of Plasticized PLA Electrospun Fiber Mats: Morphological, Thermal and Crystalline Evolution. Polymers 2020, 12, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, K.; Hyon, S.H.; Ikada, Y. Thermal characterization of polylactides. Polymer 1988, 29, 2229–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Apostolidou, D.; Tryfon, A.; Mouzakis, D.E.; Nasikas, N.K.; Kalampounias, A.G. Combined Use of Vibrational Spectroscopy, Ultrasonic Echography, and Numerical Simulations for the Non-Destructive Evaluation of 3D-Printed Materials for Defense Applications. Polymers 2026, 18, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010104

Apostolidou D, Tryfon A, Mouzakis DE, Nasikas NK, Kalampounias AG. Combined Use of Vibrational Spectroscopy, Ultrasonic Echography, and Numerical Simulations for the Non-Destructive Evaluation of 3D-Printed Materials for Defense Applications. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleApostolidou, Dimitra, Afrodite Tryfon, Dionysios E. Mouzakis, Nektarios K. Nasikas, and Angelos G. Kalampounias. 2026. "Combined Use of Vibrational Spectroscopy, Ultrasonic Echography, and Numerical Simulations for the Non-Destructive Evaluation of 3D-Printed Materials for Defense Applications" Polymers 18, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010104

APA StyleApostolidou, D., Tryfon, A., Mouzakis, D. E., Nasikas, N. K., & Kalampounias, A. G. (2026). Combined Use of Vibrational Spectroscopy, Ultrasonic Echography, and Numerical Simulations for the Non-Destructive Evaluation of 3D-Printed Materials for Defense Applications. Polymers, 18(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010104