Recycling Waste Plastics from Urban Landscapes to Porous Carbon for Clean Energy Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis of PCNS from Waste PP

2.2. Preparation of Pd-Supported Porous Carbon Nanosheets (PCNS@Pd)

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.Y.; Chen, B.S.; Guo, H.; Sun, J.L. Environmental Footprint Assessment of Plastics in China; Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J. Application of recyclable materials in the field of architectural landscape design materials under urban construction. Int. J. Mater. Prod. Technol. 2024, 69, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.J.G.; Sá, A.V. Sustainable construction solutions for outdoor public spaces: Modernity and tradition in optimising urban quality. U. Porto J. Eng. 2025, 11, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, J.E. Weathering of Plastics. In Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials, 3rd ed.; Kutz, M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Q.M.; Glaese, M.; Meng, K.; Geissen, V.; Huerta-Lwanga, E. Parks and recreational areas as sinks of plastic debris in urban sites: The case of light-density microplastics in the city of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Environments 2021, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, S.M.; Abraham, G.; Al-Qabandi, O.A.; Dashti, A.M. Investigating the effect of accelerated weathering on the mechanical and physical properties of high content plastic solid waste (PSW) blends with virgin linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE). Polym. Test. 2015, 46, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabri, A.; Tahir, F.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Environmental impacts of polypropylene (PP) production and prospects of its recycling in the GCC region. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 2245–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.D.; Liu, X.G.; Min, J.K.; Li, J.X.; Gong, J.; Wen, X.; Chen, X.C.; Tang, T.; Mijowska, E. Sustainable recycling of waste polystyrene into hierarchical porous carbon nanosheets with potential applications in supercapacitors. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 035402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.C.; Wang, H.; He, J.H. Synthesis of carbon nanotubes and nanospheres with controlled morphology using different catalyst precursors. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 325607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.C.; Jiang, Z.W.; Wen, X.; Mijowska, E.; Tang, T. Converting real-world mixed waste plastics into porous carbon nanosheets with excellent performance in the adsorption of an organic dye from wastewater. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.K.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.X.; Klingeler, R.; Wen, X.; Chen, X.C.; Zhao, X.; Tang, T.; Mijowska, E. From polystyrene waste to porous carbon flake and potential applications in supercapacitors. Waste Manag. 2019, 85, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.T.; Liu, C.J.; Wang, Z. Hydrogen storage on carbon doped with platinum nanoparticles using plasma reduction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 8277–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Q.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, W.B. Microporous carbon supported PdNi nanoalloys with adjustable alloying degree for hydrogen storage at room temperature. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 713, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Q.; Li, W.B. Pd Nanoparticle-Loaded Polyacrylonitrile-Based Microporous Carbon for Hydrogen Storage. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 11689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.D.; Yang, Z.X.; Zhu, Y.Q. Porous carbon-based materials for hydrogen storage: Advancement and challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9365–9381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węńska, K.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Gong, J.; Tang, T.; Kalenczuk, R.J.; Chen, X.C.; Mijowska, E. In situ deposition of Pd nanoparticles with controllable diameters in hollow carbon spheres for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 16179–16184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca, M.; Cendrowski, K.; Banach, P.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Mijowska, E.; Kalenczuk, R.J.; Zielińska, B. Hydrogen storage on carbon-based materials decorated with Pd nanoparticles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30461–30469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, B.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Mijowska, E.; Kalenczuk, R.J. Advances in Pd nanoparticle size decoration of mesoporous carbon spheres for energy application. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, C.; Wen, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Tang, T.; Holze, R.; Mijowska, E. Highly Efficient Conversion of Waste Plastic into Thin Carbon Nanosheets for Superior Capacitive Energy Storage. Carbon 2021, 171, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M.D.; Aranovich, G.L. Adsorption Hysteresis in Porous Solids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 205, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Luo, J.H.; Yao, Y.; Song, J.F.; Shi, Y. Room-temperature hydrogen adsorption in Pd nanoparticle decorated UiO-66-NH2 via spillover. Particuology 2024, 93, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.; Farhadian, N. Improvement of Hydrogen Adsorption on the Simultaneously Decorated Graphene Sheet with Titanium and Palladium Atoms. Langmuir 2024, 40, 13879–13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohzadi, K.; Mehrabi, M.; Shirkani, H.; Karimi, S. Laser radiation, CDs and Pd-NPs: Three influential factors to enhance the hydrogen storage capacity of porous silicon. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xiong, J.; Chen, Y.; Nie, Z. Research progress of hydrogen storage based on carbon–based materials with the spillover method at room temperature. Int. J. Green Energy 2023, 21, 1969–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kulkarni, M.V.; Gokhale, S.P.; Chikkali, S.H.; Kulkarni, C.V. Enhancing the hydrogen storage capacity of Pd-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 258, 3405–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.W.J.; Mavrikakis, M. Effects of composition and morphology on the hydrogen storage properties of transition metal hydrides: Insights from PtPd nanoclusters. Nano Energy 2019, 63, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, S.; Zacharia, R.; Hwang, S.W.; Naik, M.; Nahm, K.S. Hydrogen uptake of palladium embedded MWCNTs produced by impregnation and condensed phase reduction method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 441, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen Storage in Metal-Organic Frameworks by Bridged Hydrogen Spillover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8136–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Yang, R.T. Significantly Enhanced Hydrogen Storage in Metal-Organic Frameworks via Spillover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 128, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Kamiuchi, N.; Yoshida, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamashita, H. Hydrogen spillover-driven synthesis of high-entropy nanoparticles as a robust catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.Z.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Shuai, Y.; Tong, J.N.; Wang, D.; Ye, Y.Y.; Li, S.R. Supported Pd nanoclusters with enhanced hydrogen spillover for NOx removal via H2-SCR: The elimination of “volcano-type” behavior. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 5958–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.D.; Ostrom, C.K.; Chen, S.; Chen, A.C. High-Performance Pd-Based Hydrogen Spillover Catalysts for Hydrogen Storage. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 19875–19882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrin, P.; Kandoi, S.; Nilekar, A.U.; Mavrikakis, M. Hydrogen Adsorption, Absorption and Diffusion on and in Transition Metal Surfaces: A DFT Study. Surf. Sci. 2012, 606, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plastic Type | Representative Cases | Hazards (Highlighting Non-Degradability) |

|---|---|---|

| PP (Polypropylene) | People’s Pavilion (The Netherlands), Print Your City (Greece, partial) | Poor durability and limited recyclability after decommissioning; emits toxic gases when incinerated; remains undegraded for a long time in landfills. |

| HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene) | Tulum Plastic School (Mexico), People’s Pavilion (The Netherlands) | Highly corrosion-resistant, virtually non-degradable in natural environments; easily brittle under UV radiation, generating microplastics. |

| Mixed Plastics/Composites | Recycling Loop Proposal (France), Print Your City (Greece, partial), Toy Story Residence (India), Urban Magnetic Field (China) | Most difficult to treat mixed and inseparable composition → almost impossible to recycle again; typically disposed of via landfilling or incineration, forming long-term pollution sources. |

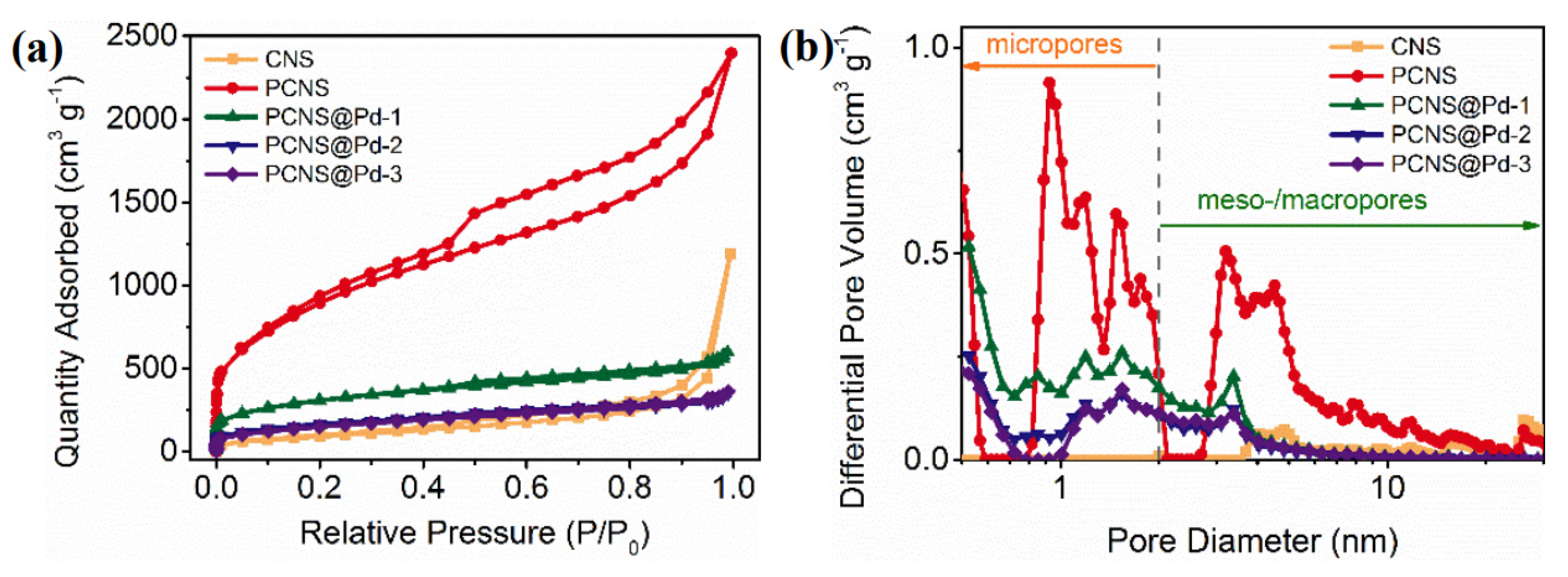

| Samples | () a |

Vt () b |

PSAV (nm) c |

PSDFT (nm) d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | 359 | 1.84 | 2.05 | 2.61 |

| PCNS | 3200 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 0.93 |

| PCNS@pd-1 | 1083 | 0.93 | 3.42 | 0.524 |

| PCNS@pd-2 | 576 | 0.55 | 3.79 | 0.524 |

| PCNS@pd-3 | 535 | 0.55 | 4.16 | 0.484 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Chen, X. Recycling Waste Plastics from Urban Landscapes to Porous Carbon for Clean Energy Storage. Polymers 2026, 18, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010105

Ma L, Chen X. Recycling Waste Plastics from Urban Landscapes to Porous Carbon for Clean Energy Storage. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Lin, and Xuecheng Chen. 2026. "Recycling Waste Plastics from Urban Landscapes to Porous Carbon for Clean Energy Storage" Polymers 18, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010105

APA StyleMa, L., & Chen, X. (2026). Recycling Waste Plastics from Urban Landscapes to Porous Carbon for Clean Energy Storage. Polymers, 18(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010105