Low-Temperature Performance and Tribological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Lubricating Oils: Effect of Molecular Weight and Hydrogenation on the Viscosity and Anti-Wear Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Initial Reagents

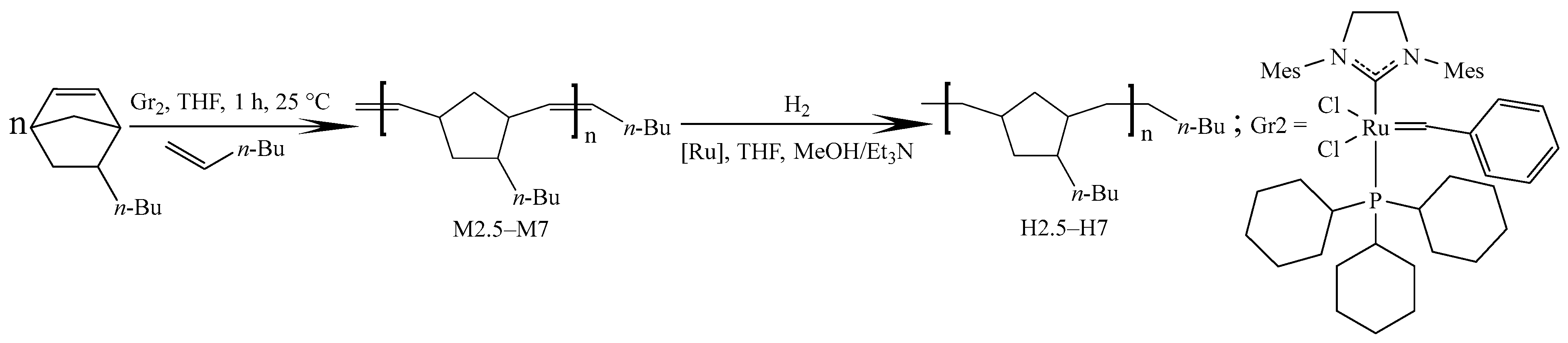

2.1.2. ROMP of 5-n-Butyl-2-norbornene Initiated by the Second-Generation Grubbs Catalyst

2.1.3. Hydrogenation of Metathesis Oligo(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene)

2.2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Metathesis Polymerization of 5-n-Butyl-2-norbornene and Subsequent One-Pot Hydrogenation of the Resulting Polyenes

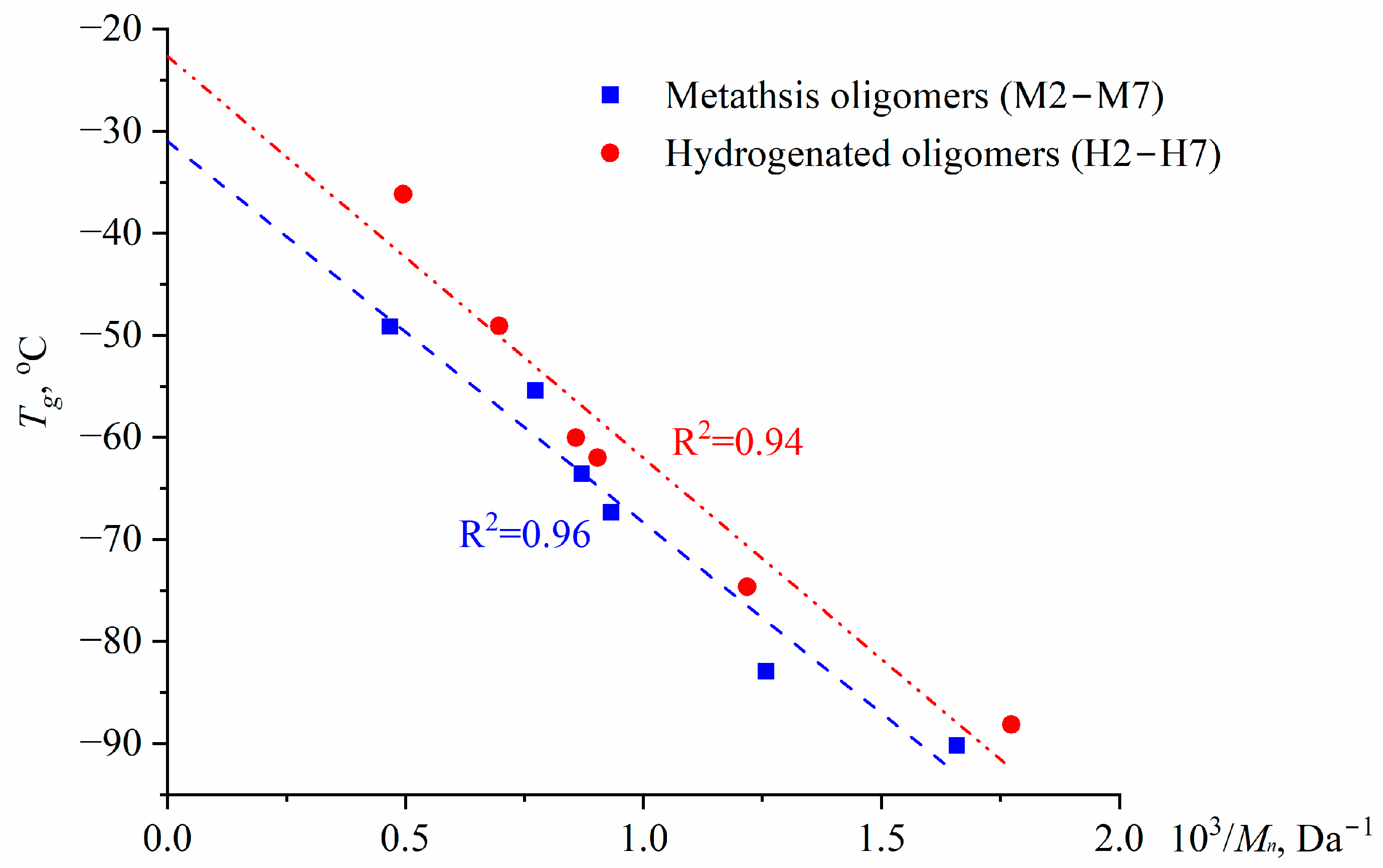

3.2. Thermophysical Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Oils

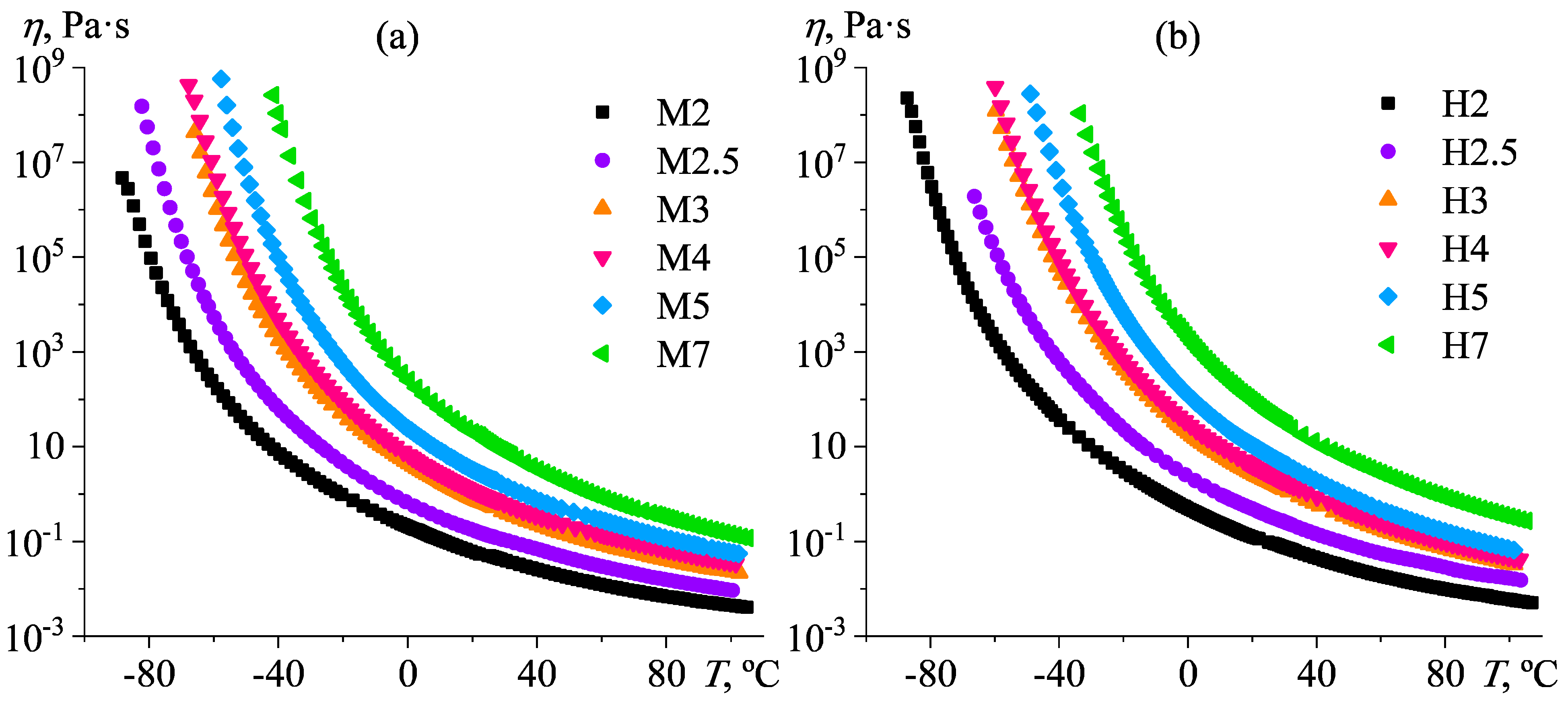

3.3. Rheological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Oils

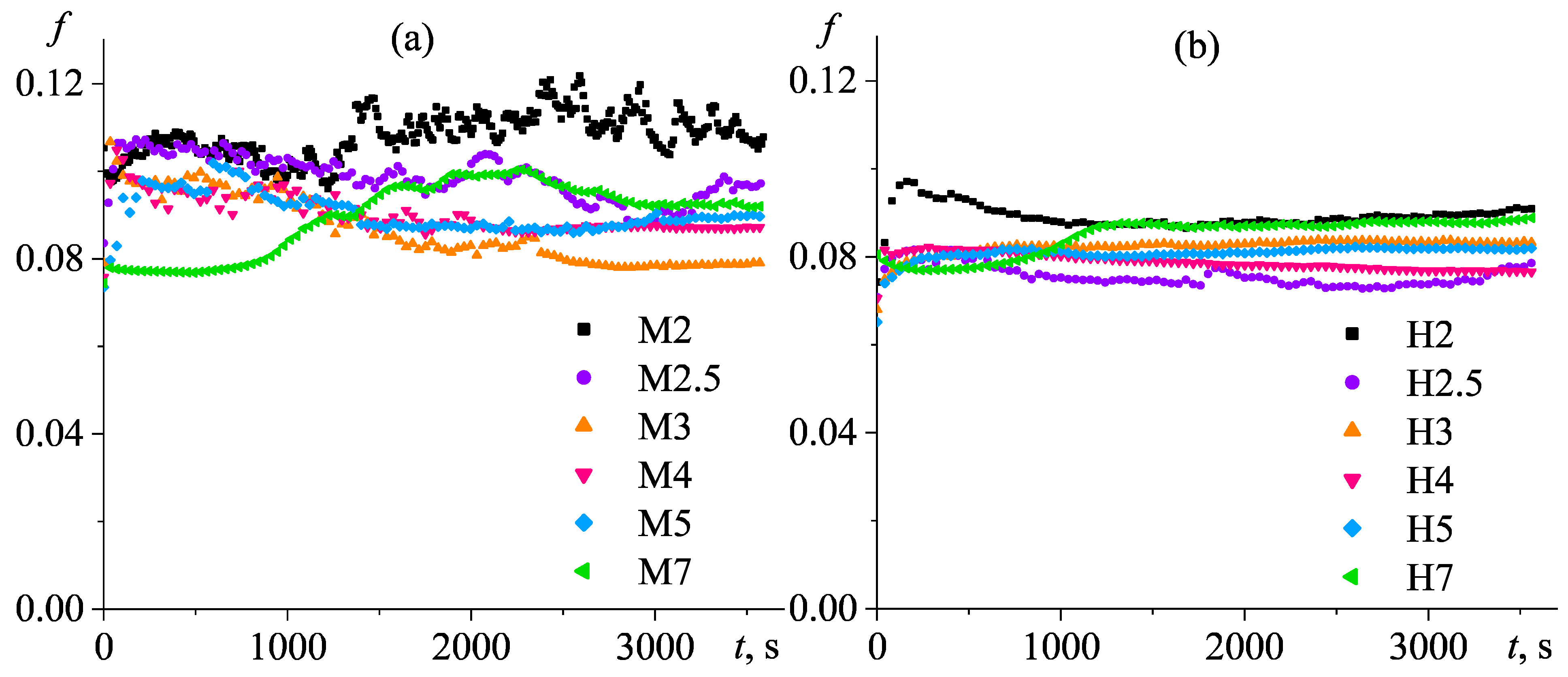

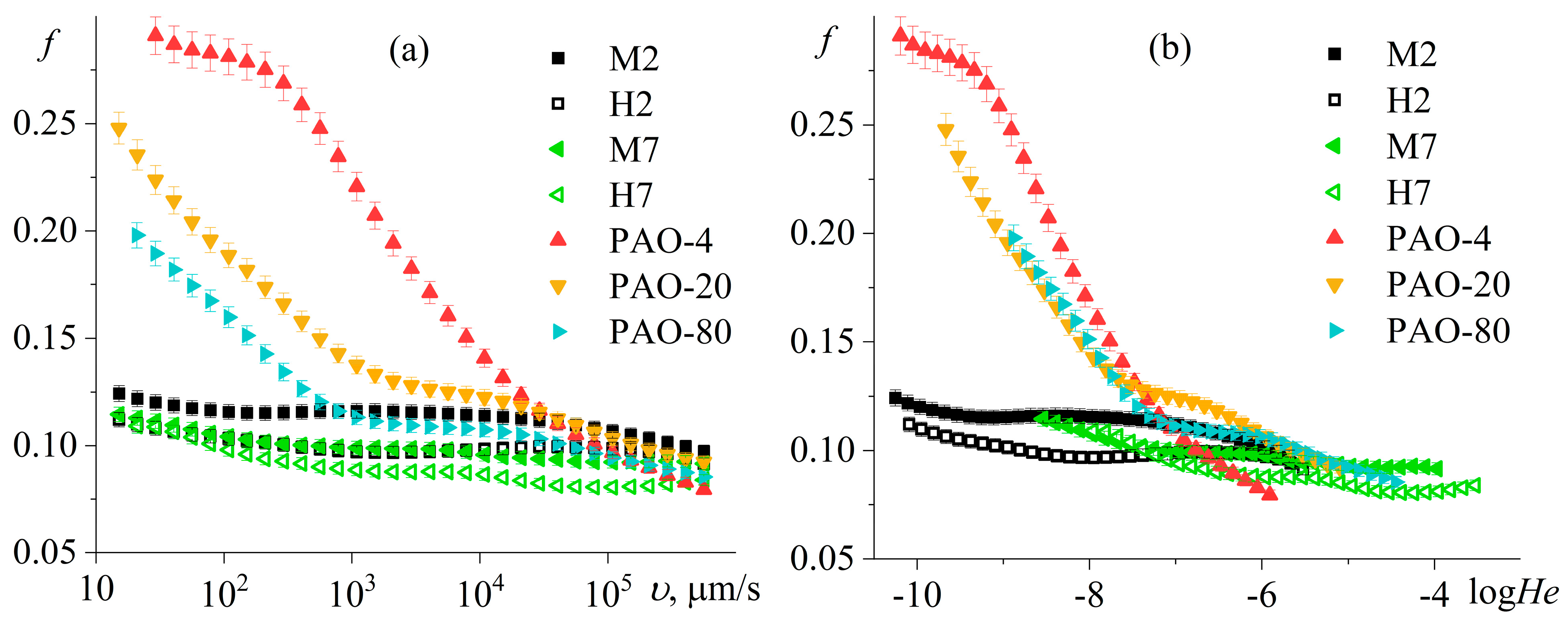

3.4. Tribological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Oils

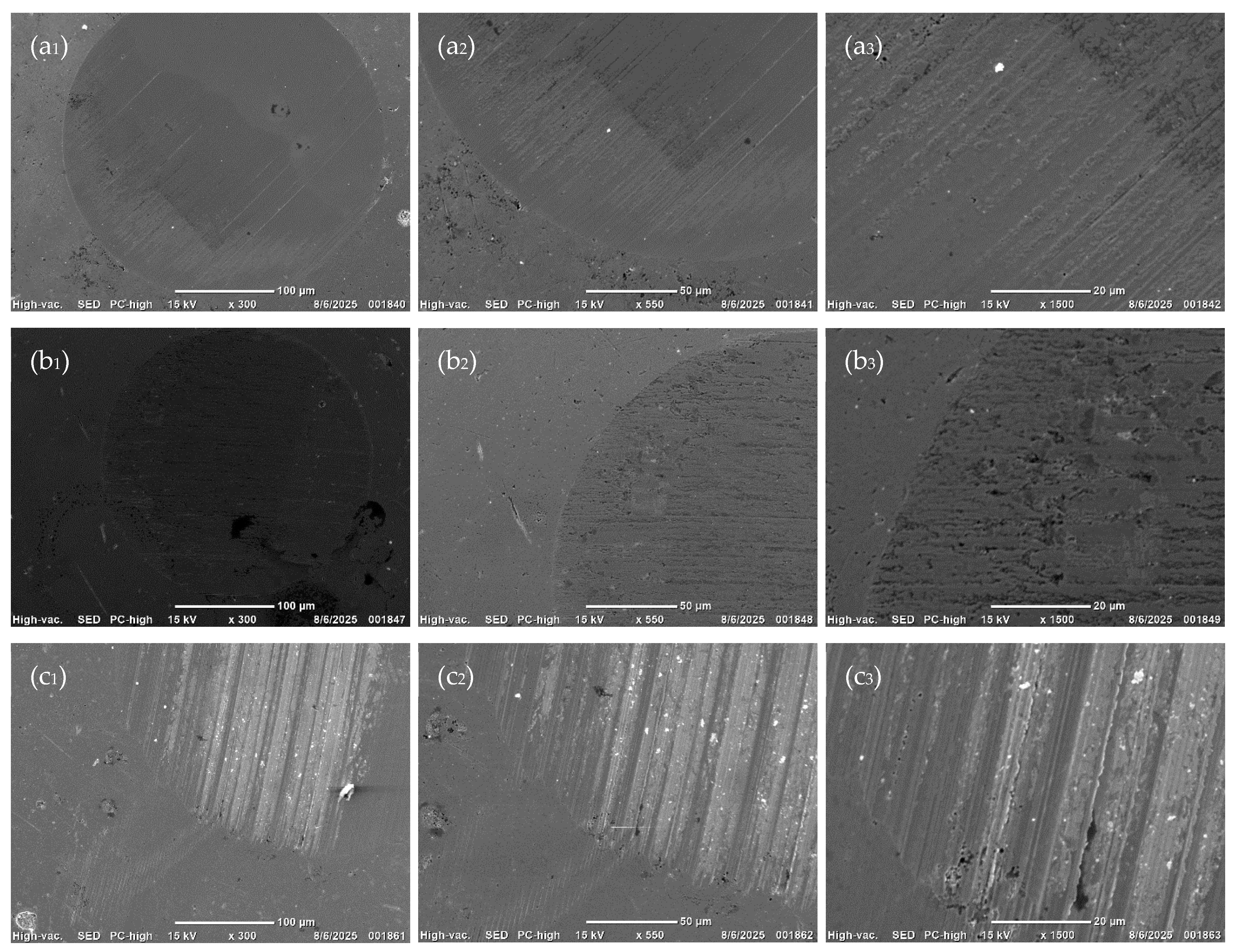

3.5. Composition and Morphology of Wear Surfaces

3.6. Origin of the Superior Anti-Wear Performance of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Oils

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, L.; Jian, Z. All-Hydrocarbon High-Refractive-Index Cyclic Olefin Polymer via ROMP. Chin. J. Chem. 2025, 43, 2963–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Kang, S.H.; Lee, M.R.; Choi, C.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.-H.; Baek, K.-Y. Synthesis of Thermo-Controlled Cyclic Olefin Polymers via Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization: Effect of Copolymerization with Flexible Modifier. Macromol. Res. 2022, 30, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Mandal, M.; Huang, G.; Wu, X.; He, G.; Kohl, P.A. Highly Conducting Anion-Exchange Membranes Based on Cross-Linked Poly(Norbornene): Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 2458–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, I.; Kilbinger, A.F.M. Unprecedented Reactivity of Terminal Olefins in Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 9643–9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielawski, C.W.; Benitez, D.; Morita, T.; Grubbs, R.H. Synthesis of End-Functionalized Poly(Norbornene)s via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 8610–8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielawski, C.W.; Grubbs, R.H. Highly Efficient Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP) Using New Ruthenium Catalysts Containing N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands. Angew. Chem. 2000, 39, 2903–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, I.; Kilbinger, A.F.M. Practical Route for Catalytic Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. JACS Au 2022, 2, 2800–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyants, V.R.; Nazemutdinova, V.R.; Zhigarev, V.A.; Sadovnikov, K.S.; Wozniak, A.I.; Morontsev, A.A.; Bermeshev, M.V. Metathesis Polymerization of 5-n-Butyl-2-Norbornene in the Presence of Dimethyl Maleate. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2023, 65, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubricants and Their Composition. In Engineering TriBology; Stachowiak, G.W., Batchelor, A.W., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; Volume 24, pp. 59–119. ISBN 978-0-444-89235-5. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, W.R.; Blain, D.A.; Galiano-Roth, A.S. Synthetics Basics Benefits of Synthetic Lubricants in Industrial. J. Synth. Lubr. 2002, 18, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, L.R. Synthetics, Mineral Oils, and Bio-Based Lubricants; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yan, L.; Luo, J. An Investigation on the Tribological Properties of Multilayer Graphene and MoS2 Nanosheets as Additives Used in Hydraulic Applications. Tribol. Int. 2016, 97, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Vinu, R. Characterization of Thermal Stability of Synthetic and Semi-Synthetic Engine Oils. Lubricants 2015, 3, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtela, M.; Pakkanen, T.A.; Nissfolk, F. Molecular Modeling of Poly-.Alpha.-Olefin Synthetic Oils. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 10267–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Mi, P.; Xu, S.; Dong, S. Structure and Properties of Poly-α-Olefins Containing Quaternary Carbon Centers. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 9142–9150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.; Rao, P.V.C.; Choudary, N.V. Poly-α-olefin-based Synthetic Lubricants: A Short Review on Various Synthetic Routes. Lubr. Sci. 2012, 24, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifant’ev, I.; Bagrov, V.; Vinogradov, A.A.; Vinogradov, A.A.; Ilyin, S.; Sevostyanova, N.; Batashev, S.; Ivchenko, P. Methylenealkane-Based Low-Viscosity Ester Oils: Synthesis and Outlook. Lubricants 2020, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifant’ev, I.E.; Vinogradov, A.A.; Vinogradov, A.A.; Sedov, I.V.; Dorokhov, V.G.; Lyadov, A.S.; Ivchenko, P.V. Structurally Uniform 1-Hexene, 1-Octene, and 1-Decene Oligomers: Zirconocene/MAO-Catalyzed Preparation, Characterization, and Prospects of Their Use as Low-Viscosity Low-Temperature Oil Base Stocks. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2018, 549, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Rosenbaum, J.M.; Hao, Y.; Lei, G.-D. Premium Lubricant Base Stocks by Hydroprocessing. In Springer Handbook of Petroleum Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1015–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Peng, C.; Zhang, A.; Liang, X.; Yan, Y. Correlation between the Molecular Structure and Viscosity Index of CTL Base Oils Based on Ridge Regression. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 18887–18896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ling, H.; Shen, B.; Li, K.; Ng, S. Evaluation of Hydroisomerization Products as Lube Base Oils Based on Carbon Number Distribution and Hydrocarbon Type Analysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 2006, 87, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfiryev, Y.; Shuvalov, S.; Popov, P.; Kolybelsky, D.; Petrova, D.; Ivanov, E.; Tonkonogov, B.; Vinokurov, V. Effect of Base Oil Nature on the Operational Properties of Low-Temperature Greases. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 11946–11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Chau, A.; Wan, Y.; Lu, Z.; Huang, F. Fabrication and Tribological Properties of a Multiply-Alkylated Cyclopentane/Reduced Graphene Oxide Composite Ultrathin Film. Carbon 2013, 65, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pu, J.; Bai, M. Precise Positioning of Lubricant on a Surface Using the Local Anodic Oxide Method. Langmuir 2009, 25, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Kudaibergenov, N.Z.; Wei, J.; Chen, F. Dynamic Behaviors of Confined Lubricant Molecules Explored via Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 22118–22133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Q.; Mo, Y.F.; Bai, M. Preparation and Tribological Behaviour of Multiply-Alkylated Cyclopentane-1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-Perfluorodecyltrichlorosilane Dual-Layer Film on Diamond-like Carbon. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2009, 223, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, J.; Mo, Y.; Bai, M. Effect of Multiply-Alkylated Cyclopentane (MAC) on Durability and Load-Carrying Capacity of Self-Assembled Monolayers on Silicon Wafer. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 301, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.R.; Shogrin, B.A.; Jansen, M.J. Research on Liquid Lubricants for Space Mechanisms. J. Synth. Lubr. 2000, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, L.; Qiao, D.; Feng, D.; Wang, H. Vacuum Tribological Performance of Phosphonium-Based Ionic Liquids as Lubricants and Lubricant Additives of Multialkylated Cyclopentanes. Tribol. Int. 2013, 66, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemutdinova, V.R.; Zhigarev, V.A.; Ilyin, S.O.; Morontsev, A.A.; Borisov, R.S.; Zimens, M.E.; Wozniak, A.I.; Sadovnikov, K.S.; Maximov, A.L.; Bermeshev, M.V. Metathesis of Alkylnorbornenes as a New Route to Synthetic Oils: The Synthesis and Rheo-Tribological Behavior of 5- n -Butylnorbornene Oligomers. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 14042–14054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, A.I.; Bermesheva, E.V.; Borisov, I.L.; Volkov, A.V.; Petukhov, D.I.; Gavrilova, N.N.; Shantarovich, V.P.; Asachenko, A.F.; Topchiy, M.A.; Finkelshtein, E.S.; et al. Switching on/Switching off Solubility Controlled Permeation of Hydrocarbons through Glassy Polynorbornenes by the Length of Side Alkyl Groups. J. Memb. Sci. 2022, 641, 119848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatjopoulos, J.D.; Register, R.A. Synthesis and Properties of Well-Defined Elastomeric Poly(Alkylnorbornene)s and Their Hydrogenated Derivatives. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 10320–10322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, B. The Stribeck Memorial Lecture. Tribol. Int. 2003, 36, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, T.G.; Flory, P.J. Second-Order Transition Temperatures and Related Properties of Polystyrene. I. Influence of Molecular Weight. J. Appl. Phys. 1950, 21, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, T.G.; Flory, P.J. The Glass Temperature and Related Properties of Polystyrene. Influence of Molecular Weight. J. Polym. Sci. 1954, 14, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadykova, A.Y.; Strelets, L.A.; Ilyin, S.O. Infrared Spectral Classification of Natural Bitumens for Their Rheological and Thermophysical Characterization. Molecules 2023, 28, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadykova, A.Y.; Ilyin, S.O. Compatibility and Rheology of Bio-Oil Blends with Light and Heavy Crude Oils. Fuel 2022, 314, 122761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O.; Melekhina, V.Y.; Kostyuk, A.V.; Smirnova, N.M. Hot-Melt and Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives Based on Styrene-Isoprene-Styrene Triblock Copolymer, Asphaltene/Resin Blend and Naphthenic Oil. Polymers 2022, 14, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyin, S.O.; Strelets, L.A. Basic Fundamentals of Petroleum Rheology and Their Application for the Investigation of Crude Oils of Different Natures. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuero, A.G.; Sayago, A.; González, A.G. The Correlation Coefficient: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2006, 36, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.L.; Well, A.D. Research Design and Statistical Analysis, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Verdier, S.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Silva, A.M.S.; Alkilde, O.F.; Hansen, J.A. A Critical Approach to Viscosity Index. Fuel 2009, 88, 2199–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Rheology and Miscibility of Linear/Hyperbranched Polydimethylsiloxane Blends and an Abnormal Decrease in Their Viscosity. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 6818–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O. Structural Rheology in the Development and Study of Complex Polymer Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.L. A Critical Assessment of the Low-Temperature Viscosity Requirements of SAE J300 and Its Future; SAE Technical Paper: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tervo, J.; Junttila, J.; Lämsä, V.; Savolainen, M.; Ronkainen, H. Hybrid Methodology Development for Lubrication Regimes Identification Based on Measurements, Simulation, and Data Clustering. Tribol. Int. 2024, 195, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, P.R.; Goddard, J.D.; Tam, W. Ring Strain Energies: Substituted Rings, Norbornanes, Norbornenes and Norbornadienes. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 8103–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecim, B.; Winer, W.O. Transient Temperatures in the Vicinity of an Asperity Contact. J. Tribol. 1985, 107, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovich, P.N.; Tkachuk, D.V. Temperature Distribution over Contact Area and “Hot Spots” in Rubbing Solid Contact. Tribol. Int. 2006, 39, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddad, Y.; Magnier, V.; Dufrénoy, P.; De Saxcé, G. Heat Partition and Surface Temperature in Sliding Contact Systems of Rough Surfaces. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 137, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Olefin/Catalyst Ratio | Characteristics of Metathesis Products | Characteristics of Hydrogenated Products | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [ButNB]/[CTA] + [Gr2] | [ButNB] + [CTA]/ [Gr2] | № | Mn c, kDa | Ð c | P | № | Mn c, kDa | Ð c |

| 6.9 a | 2.6 × 103 | M7 | 2.14 | 1.6 | 14 | H7 | 2.02 | 1.7 |

| 5.0 a | 3.4 × 103 | M5 | 1.29 | 1.8 | 8 | H5 | 1.44 | 1.7 |

| 4.0 | 4.1 × 103 | M4 | 1.15 | 2.0 | 7 | H4 | 1.17 | 2.0 |

| 2.9 | 4.5 × 103 | M3 | 1.07 | 2.0 | 7 | H3 | 1.11 | 2.0 |

| 2.5 | 4.6 × 103 | M2.5 | 0.80 | 1.9 | 5 | H2.5 | 0.82 | 1.9 |

| 2.0 a,b | 4.6 × 103 | M2 | 0.60 | 1.7 | 3 | H2 | 0.56 | 1.6 |

| Sample | v40 °C, mm2/s | v100 °C, mm2/s | f | Dscar, μm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO-4 | 14.3 | 3.61 | 0.104 ± 0.003 | 407 ± 14 |

| PAO-20 | 137.0 | 19.1 | 0.103 ± 0.003 | 352 ± 32 |

| PAO-80 | 674.7 | 77.7 | 0.086 ± 0.004 | 373 ± 12 |

| № | Elemental Composition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | O | Si | Fe | |||||

| Weight Fraction, % | Atom Fraction, % | Weight Fraction, % | Atom Fraction, % | Weight Fraction, % | Atom Fraction, % | Weight Fraction, % | Atom Fraction, % | |

| Initial surface a | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 97.7 ± 0.5 | 90.7 ± 2.0 |

| M7 | 2.1 | 8.4 | 4.4 | 12.8 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 93.2 | 78.4 |

| H7 | 3.1 | 11.4 | 5.1 | 14.4 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 91.5 | 73.7 |

| PAO-4 | 4.5 | 18.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 95.1 | 81.1 |

| T, °C | M2.5 | M3 | M4 | H2.5 | H3 | H4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.899 | 0.909 | 0.911 | 0.887 | 0.898 | - |

| 20 | 0.888 | 0.898 | 0.901 | 0.877 | 0.888 | 0.890 |

| 40 | 0.866 | 0.877 | 0.879 | 0.855 | 0.867 | 0.869 |

| Sample | T1000 Pa·s, °C | η−40 °C, Pa·s | η40 °C, mPa·s | η100 °C, mPa·s | VI | E0 °C, kJ/mol | E75 °C, kJ/mol | SAE J300 Grade | SAE J306 Grade | f | Dscar, μm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 a | −66.3 | 7.49 | 25.7 | 4.44 | 129 | 40.9 | 27.0 | 0W-8 | 70W | 0.111 ± 0.004 | 359 ± 22 |

| M2.5 | −53.7 | 66.6 | 68.9 | 9.39 | 141 | 48.4 | 30.8 | 15W-30 | 75W-85 | 0.093 ± 0.003 | 254 ± 21 |

| M3 | −37.2 | 1900 | 229 | 23.5 | 147 | 60.5 | 37.0 | 25W | 80W-140 | 0.079 ± 0.001 | 260 ± 19 |

| M4 | −33.3 | 4800 | 345 | 35.9 | 168 | 62.5 | 36.1 | too viscous | 85W-250 | 0.087 ± 0.001 | 238 ± 20 |

| M5 | −22.8 | 97,000 | 761 | 59.0 | 158 | 75.1 | 42.2 | too viscous | 85W-250 | 0.088 ± 0.001 | 293 ± 33 |

| M7 | −7.3 | 108 | 3380 | 142 | 145 | 102.1 | 44.6 | too viscous | 250 | 0.094 ± 0.002 | 307 ± 17 |

| H2 a | −57.3 | 38.4 | 44.9 | 5.92 | 103 | 49.5 | 29.6 | 10W-12 | 75W | 0.089 ± 0.001 | 203 ± 50 |

| H2.5 | −42.1 | 640 | 143 | 16.8 | 150 | 58.7 | 34.8 | 25W-50 | 80W-110 | 0.075 ± 0.002 | 265 ± 65 |

| H3 | −24.0 | 52,000 | 610 | 34.1 | 101 | 77.6 | 43.2 | too viscous | 85W-250 | 0.083 ± 0.001 | 125 ± 8 |

| H4 | −21.9 | 90,000 | 890 | 46.3 | 109 | 76.7 | 45.1 | too viscous | 250 | 0.077 ± 0.001 | 213 ± 17 |

| H5 | −11.8 | 4 × 106 | 1920 | 69.7 | 100 | 96.3 | 50.1 | too viscous | 250 | 0.082 ± 0.001 | 118 ± 4 |

| H7 | 3.9 | >109 | 11,900 | 334 | 157 | 118.8 | 56.4 | too viscous | 250 | 0.088 ± 0.001 | 289 ± 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazemutdinova, V.R.; Ilyin, S.O.; Morontsev, A.A.; Makarov, I.S.; Wozniak, A.I.; Bermeshev, M.V. Low-Temperature Performance and Tribological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Lubricating Oils: Effect of Molecular Weight and Hydrogenation on the Viscosity and Anti-Wear Activity. Polymers 2025, 17, 3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243333

Nazemutdinova VR, Ilyin SO, Morontsev AA, Makarov IS, Wozniak AI, Bermeshev MV. Low-Temperature Performance and Tribological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Lubricating Oils: Effect of Molecular Weight and Hydrogenation on the Viscosity and Anti-Wear Activity. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243333

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazemutdinova, Valeriia R., Sergey O. Ilyin, Aleksandr A. Morontsev, Igor S. Makarov, Alyona I. Wozniak, and Maxim V. Bermeshev. 2025. "Low-Temperature Performance and Tribological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Lubricating Oils: Effect of Molecular Weight and Hydrogenation on the Viscosity and Anti-Wear Activity" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243333

APA StyleNazemutdinova, V. R., Ilyin, S. O., Morontsev, A. A., Makarov, I. S., Wozniak, A. I., & Bermeshev, M. V. (2025). Low-Temperature Performance and Tribological Properties of Poly(5-n-butyl-2-norbornene) Lubricating Oils: Effect of Molecular Weight and Hydrogenation on the Viscosity and Anti-Wear Activity. Polymers, 17(24), 3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243333