Impact of EVOH, Ormocer® Coating, and Printed Labels on the Recyclability of Polypropylene for Packaging Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

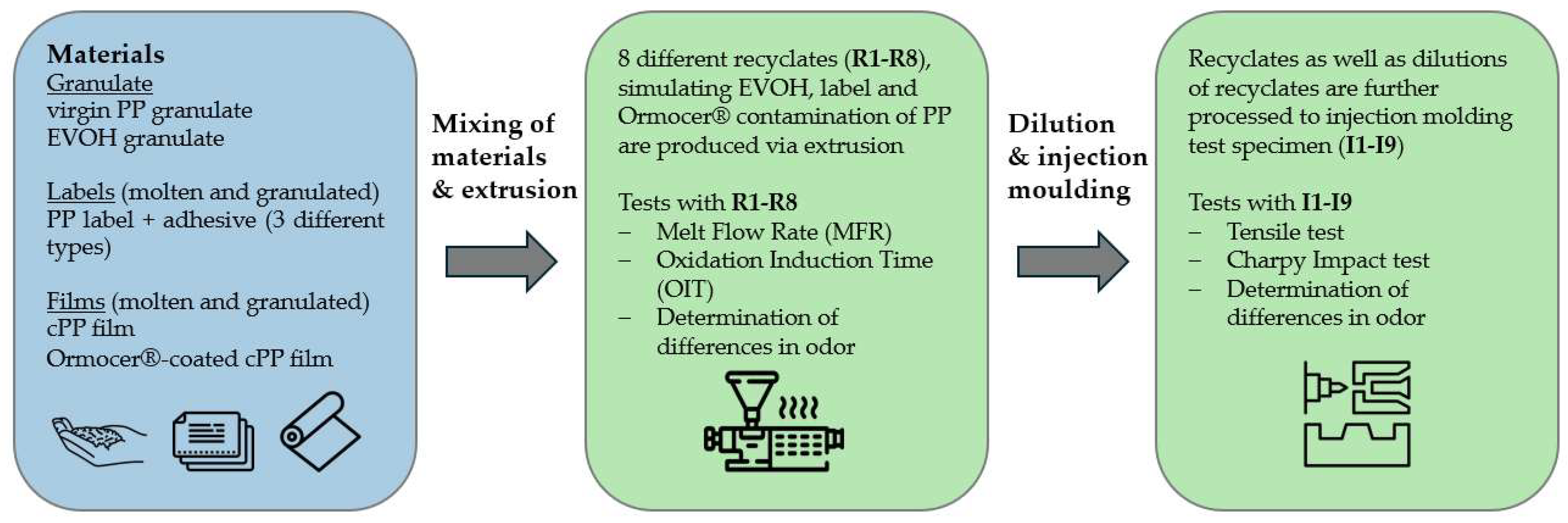

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Barrier Materials

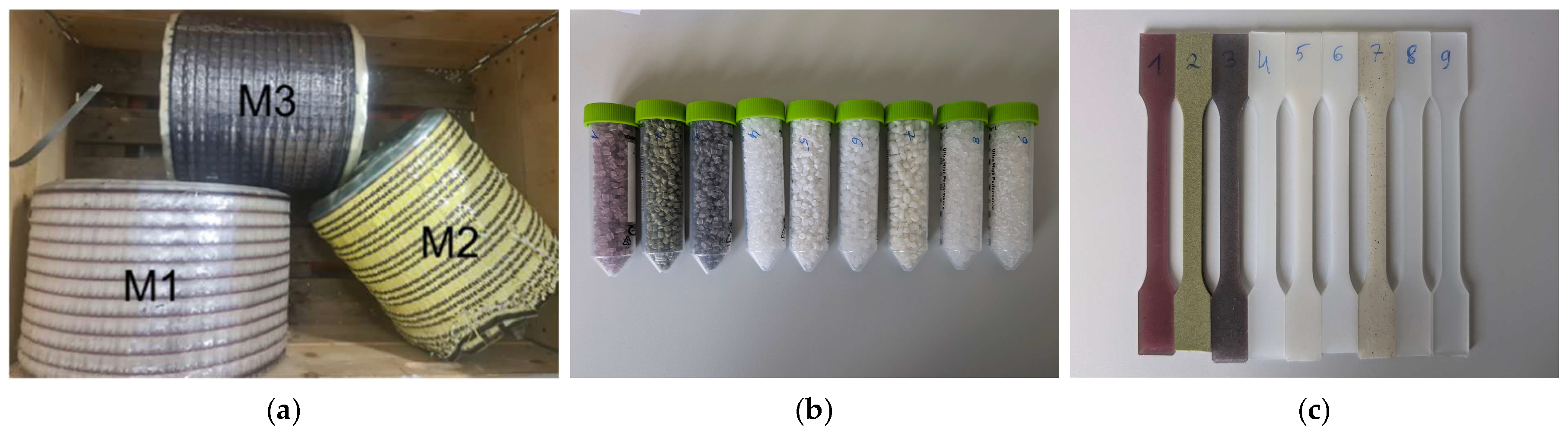

2.2. Polymer Granulates, Films and Label Materials

- Polypropylene copolymer granulate virgin material (virgin PP granulate);

- EVOH granulate;

- Oriented polypropylene-label material, red/white colored, 52 µm thickness with solvent acrylate-based adhesive type 1 (PP label + adhesive type 1);

- Oriented polypropylene-label material, yellow/black colored, 52 µm thickness with rubber-based adhesive type 2 (PP label + adhesive type 2);

- Oriented polypropylene-label material, violet/black colored, 52 µm thickness with ultraviolet acrylate-based adhesive type 3 (PP label + adhesive type 3);

- Cast polypropylene film with 70 µm thickness (cPP film);

- Cast polypropylene film with a thickness of 70 µm, coated on a semi-industrial scale by Fraunhofer ISC with Ormocer® CBS004. The coating was applied at a line speed of 5 m/min and subsequently cured at 100 °C for 20 s. (Ormocer®-coated cPP film).

2.3. Production of Recyclates via Twin-Screw Extrusion

- R1 (PP label 1): 50% PP label + adhesive type 1, 50% virgin PP granulate;

- R2 (PP label 2): 50% PP label + adhesive type 2, 50% virgin PP granulate;

- R3 (PP label 3): 50% PP label + adhesive type 3, 50% virgin PP granulate;

- R4 (PP granulate with EVOH): 90% virgin PP granulate, 10% EVOH granulate;

- R5 (cPP film with EVOH): 90% cPP film, 10% EVOH granulate;

- R6 (cPP film): 100% cPP film;

- R7 (cPP film coated with Ormocer®): 100% Ormocer®-coated cPP film;

- R8 (PP granulate): 100% virgin PP granulate.

2.4. Production of Tensile and Charpy Impact Test Specimen via Injection Molding

2.5. Method Description

2.5.1. Tensile Test According to ÖN EN ISO 527-2 [31]

2.5.2. Impact Properties (Charpy) According to ISO 179-1 [32]

2.5.3. MFR According to ÖN EN ISO 1133-1/A [33]

2.5.4. Determination of OIT, Dynamic by Means of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) According to EN ISO 11357-6 [34]

2.5.5. Determination of Differences in Odor According to DIN 10955 [35]

3. Results

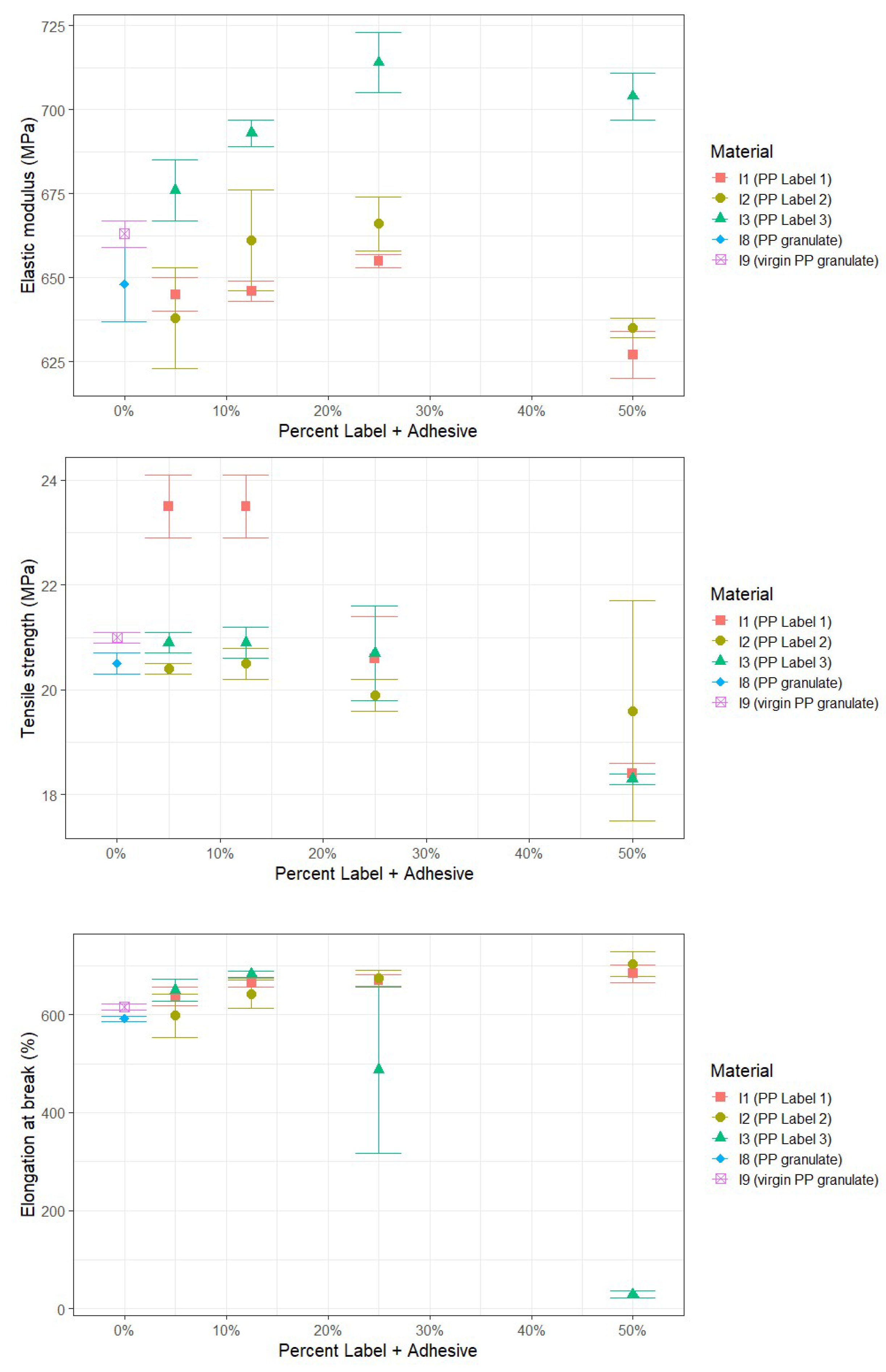

3.1. Determination of Tensile Properties

3.1.1. Impact of Labels on Tensile Properties

3.1.2. Impact of EVOH and Ormocer® Coating on Tensile Properties

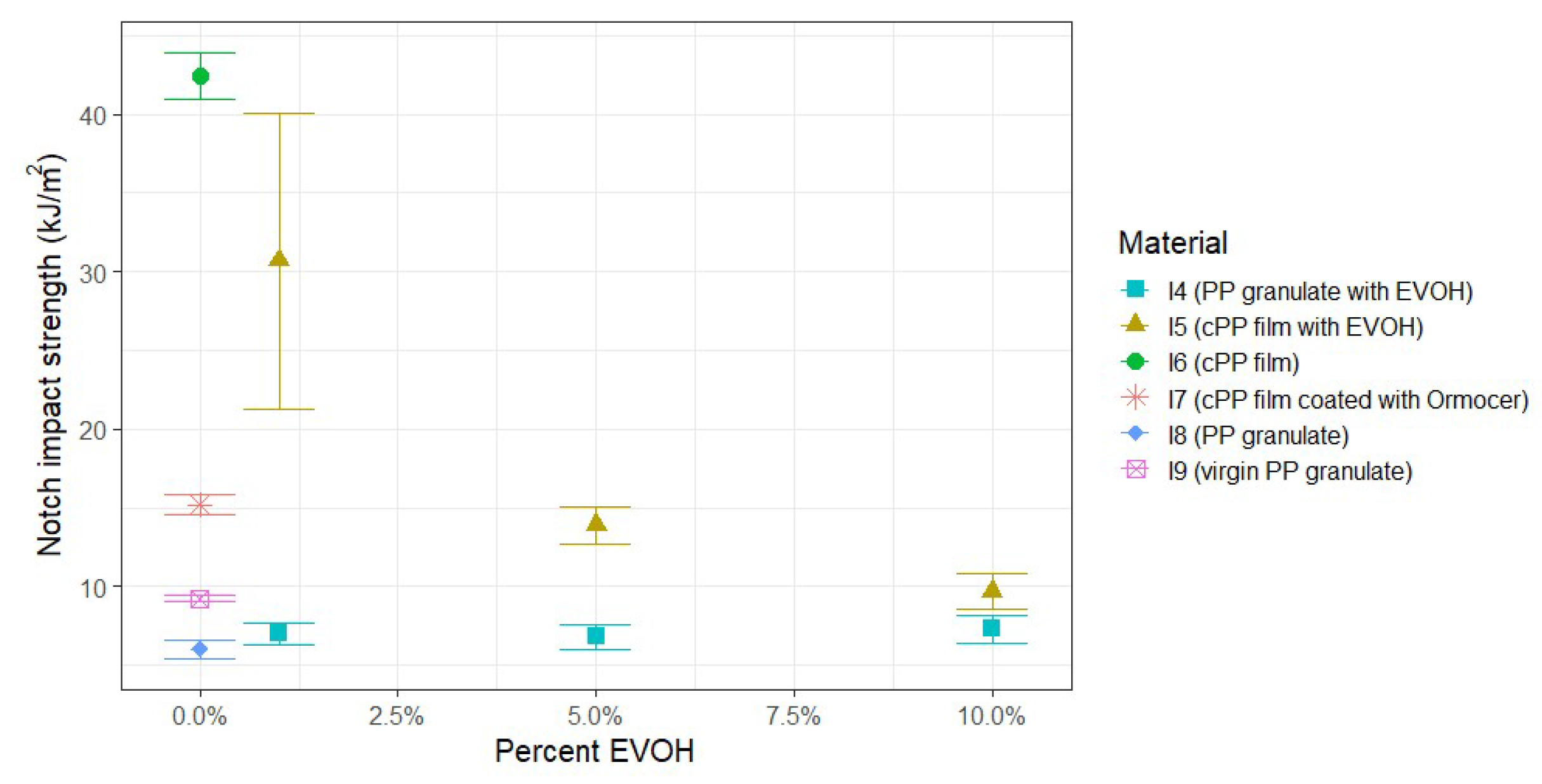

3.2. Determination of Impact Properties (Charpy)

3.2.1. Impact of Labels on Charpy Impact Properties

3.2.2. Impact of EVOH and Ormocer® Coating on Charpy Impact Properties

3.3. Determination of MFR

3.4. Determination of OIT

3.5. Determination of Differences in Odor

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges in Meeting EU Packaging Waste Regulations

4.2. Mechanical Properties of Recycled PP

4.3. MFR of Recycled PP

4.4. Thermo-Oxidative Stability of Recycled PP

4.5. Odor Characteristics of Recycled PP

5. Conclusions

- Single-cycle recycling of virgin PP without colors, adhesives and EVOH had little impact on the tensile properties, but the impact strength decreased notably.

- Low concentrations of PP labels (5–12.5%) had a minimal effect on the mechanical properties of the recyclates, whereas at 50% label content, a marked reduction in mechanical performance was observed, depending on the adhesive used.

- EVOH increased the elastic modulus of the recyclates; however, a considerable reduction in impact strength was observed in recycled cPP films containing EVOH.

- Ormocer® coating led to a decrease in both tensile and impact strength, likely due to particle formation during processing which acted as defects.

- Single-cycle recycling of virgin PP without colors, adhesives and EVOH did not affect the MFR of PP.

- Labels had varying effects on MFR depending on adhesive type, while the addition of EVOH increased MFR. Ormocer® had minimal impact on MFR, though its influence remains underexplored.

- Single-cycle recycling of virgin PP without colors, adhesives and EVOH did not affect the OIT.

- Slightly higher oxidation stability was observed in PP recyclates containing EVOH.

- PP recyclates containing labels as well as the recycled Ormocer®-coated cPP film showed pronounced differences in odor compared to both the PP recyclate and the virgin PP granulate.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plastics Recyclers Europe (Eunomia). Flexible Film Market in Europe: State of Play—Production, Collection and Recycling Data. Available online: https://743c8380-22c6-4457-9895-11872f2a708a.filesusr.com/ugd/dda42a_ff8049bc82bd408faee0d2ba4a148693.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Anukiruthika, T.; Sethupathy, P.; Wilson, A.; Kashampur, K.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Multilayer Packaging: Advances in Preparation Techniques and Emerging Food Applications. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2020, 19, 1156–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favaro, S.L.; Pereira, A.G.B.; Fernandes, J.R.; Baron, O.; Da Silva, C.T.P.; Moisés, M.P.; Radovanovic, E. Outstanding Impact Resistance of Post-Consumer HDPE/Multilayer Packaging Composites. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.L. Food Packaging and Shelf Life: A Practical Guide; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4200-7844-2. [Google Scholar]

- Horodytska, O.; Valdés, F.J.; Fullana, A. Plastic Flexible Films Waste Management—A State of Art Review. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, T.W.; Frelka, N.; Shen, Z.; Chew, A.K.; Banick, J.; Grey, S.; Kim, M.S.; Dumesic, J.A.; Van Lehn, R.C.; Huber, G.W. Recycling of Multilayer Plastic Packaging Materials by Solvent-Targeted Recovery and Precipitation. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba7599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.T.D.M.; Ek, M.; Östmark, E.; Gällstedt, M.; Karlsson, S. Recycling of Multi-Material Multilayer Plastic Packaging: Current Trends and Future Scenarios. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 176, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Packaging and Packaging Waste, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and Repealing Directive 94/62/EC COM/2022/677 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022PC0677 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Bauer, A.-S.; Tacker, M.; Uysal-Unalan, I.; Cruz, R.M.S.; Varzakas, T.; Krauter, V. Recyclability and Redesign Challenges in Multilayer Flexible Food Packaging—A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, M.Z.; Ebrahimi, A.; Yousefi, M.; Ahmadi, S.; Farhoodi, M.; Alizadeh, A.M.; Taslikh, M. Strategies for Producing Improved Oxygen Barrier Materials Appropriate for the Food Packaging Sector. Food Eng. Rev. 2020, 12, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokwena, K.K.; Tang, J. Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol: A Review of Barrier Properties for Packaging Shelf Stable Foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, C.; Luyten, W.; Herremans, G.; Peeters, R.; Carleer, R.; Buntinx, M. Recent Updates on the Barrier Properties of Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer (EVOH): A Review. Polym. Rev. 2018, 58, 209–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastics Recyclers Europe. Recyclass: Design for Recycling Guidelines Natural PP Flexible Films for Household and Commercial Packaging. Available online: https://recyclass.eu/guidelines/natural-pp-flexible-films/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Cyclos HTP: Verification and Examination of Recyclability. Available online: https://www.cyclos-htp.de/publications/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- CEFLEX. CEFLEX—Designing for a Circular Economy (D4ACE) Technical Report—Recyclability of Polyolefin-Based Flexible Packaging. Available online: https://guidelines.ceflex.eu/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Amberg-Schwab, S. Functional Barrier Coatings on the Basis of Hybrid Polymers. In Handbook of Sol-Gel Science and Technology; Klein, L., Aparicio, M., Jitianu, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-3-319-19454-7. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, K.-H.; Amberg-Schwab, S.; Rose, K.; Schottner, G. Functionalized Coatings Based on Inorganic–Organic Polymers (ORMOCER®s) and Their Combination with Vapor Deposited Inorganic Thin Films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 111, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg-Schwab, S.; Hoffmann, M.; Bader, H.; Gessler, M. Inorganic-Organic Polymers with Barrier Properties for Water Vapor, Oxygen and Flavors. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 1998, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharbafian, F.; Tosic, K.; Schmiedt, R.; Novak, M.; Krainz, M.; Rainer, B.; Apprich, S. Investigation and Comparison of Alternative Oxygen Barrier Coatings for Flexible PP Films as Food Packaging Material. Coatings 2024, 14, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.-H.; Wolter, H. Synthesis, Properties and Applications of Inorganic–Organic Copolymers (ORMOCER®s). Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1999, 4, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg-Schwab, S.; Müller, K.; Somorowsky, F.; Sängerlaub, S. UV-Activated, Transparent Oxygen Scavenger Coating Based on Inorganic–Organic Hybrid Polymer (ORMOCER®) with High Oxygen Absorption Capacity. Coatings 2023, 13, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmert, K.; Amberg-Schwab, S.; Braca, F.; Bazzichi, A.; Cecchi, A.; Somorowsky, F. bioORMOCER®—Compostable Functional Barrier Coatings for Food Packaging. Polymers 2021, 13, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food Packaging—Roles, Materials, and Environmental Issues. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R39–R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.-P. Managing Plastic Waste—Sorting, Recycling, Disposal, and Product Redesign. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 15722–15738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIM—European Brands Association Pioneering Digital Watermarks|Holy Grail 2.0. Available online: https://www.digitalwatermarks.eu/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Schmidt, J.; Auer, M.; Moesslein, J.; Wendler, P.; Wiethoff, S.; Lang-Koetz, C.; Woidasky, J. Challenges and Solutions for Plastic Packaging in a Circular Economy. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2021, 93, 1751–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RecyClass. RecyClass Design Book—A Step-by-Step Guide to Plastic Packaging Recyclability—Version 2.0. Available online: https://recyclass.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/RecyClass-Design-Book_July-2025.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Gregorio, F.D.; Potaufeux, J.-E.; Legnini, M. RecyClass Design for Recycling Guidelines. Available online: https://recyclass.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/221214_RecyClass-for-Beginners_DfR-Guidelines_presentation.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- ISO 3167:2014; Plastics—Multipurpose Test Specimens. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ÖNORM EN ISO 527-2:2025; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- ISO 179-1:2023; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties—Part 1: Non-Instrumented Impact Test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ÖNORM EN ISO 1133-1:2011; Plastics—Determination of the Melt Mass-Flow Rate (MFR) and Melt Volume-Flow Rate (MVR) of Thermoplastics—Part 1: Standard Method. Austrian Standards International: Vienna, Austria, 2012.

- ISO 11357-1:2023; Plastics—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)—Part 1: General principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- DIN 10955; Sensory Analysis—Testing of Food Contact Materials and Articles (FCM). Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN): Berlin, Germany, 2024.

- DIN EN ISO 5495:2016; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—Paired Comparison Test (ISO 5495:2005 + Cor 1:2006 + Amd 1:2016; German Version EN ISO 5495:2007 + A1:2016). Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN): Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- Hinczica, J.; Messiha, M.; Koch, T.; Frank, A.; Pinter, G. Influence of Recyclates on Mechanical Properties and Lifetime Performance of Polypropylene Materials. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2022, 42, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsman, P.; Fiorio, R. Long Term Thermo-Oxidative Degradation and Stabilization of Polypropylene (PP) and the Implications for Its Recyclability. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 208, 110260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.-F.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, P.; Hu, C.-Y.; Wang, Z.-W. Characterization of Odors and Volatile Organic Compounds Changes to Recycled High-Density Polyethylene through Mechanical Recycling. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 208, 110263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, E.; Prielinger, L.; Sharp, V.; Rainer, B.; Kirchnawy, C.; Rung, C.; Gruner, A.; Juric, M.; Springer, A. Safety Assessment of Recycled Plastics from Post-Consumer Waste with a Combination of a Miniaturized Ames Test and Chromatographic Analysis. Recycling 2023, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.-Z.; Vera, P.; Nerín, C.; Lin, Q.-B.; Zhong, H.-N. Safety Concerns of Recycling Postconsumer Polyolefins for Food Contact Uses: Regarding (Semi-)Volatile Migrants Untargetedly Screened. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.K.; Christiansen, J.D.; Daugaard, A.E.; Astrup, T.F. Closing the Loop for PET, PE and PP Waste from Households: Influence of Material Properties and Product Design for Plastic Recycling. Waste Manag. 2019, 96, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumnate, C.; Rudolph, N.; Sarmadi, M. Recycling of Polypropylene/Polyethylene Blends: Effect of Chain Structure on the Crystallization Behaviors. Polymers 2019, 11, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyie, K.M.; Budin, S.; Martinus, N.; Salleh, Z.; Mohd Masdek, N.R.N. Tensile and Flexural Investigation on Polypropylene Recycling. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1174, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-W.; Peng, H.-S. Number of Times Recycled and Its Effect on the Recyclability, Fluidity and Tensile Properties of Polypropylene Injection Molded Parts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikrishnan, S.; Jubinville, D.; Tzoganakis, C.; Mekonnen, T.H. Thermo-Mechanical Degradation of Polypropylene (PP) and Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Blends Exposed to Simulated Recycling. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 182, 109390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.G.; Piaia, M.; Ceni, G. Analysis of Impact and Tensile Properties of Recycled Polypropylene. Int. J. Mater. Eng. 2017, 7, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossnikl, J.; Pinter, E.; Jones, M.P.; Koch, T.; Archodoulaki, V.-M. Unexpected Obstacles in Mechanical Recycling of Polypropylene Labels: Are Ambitious Recycling Targets Achievable? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 200, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, I.; Fellner, K.; Fischer, J. Influence of Macroscopic Contaminations on Mechanical Properties of Model and Post-Consumer Polypropylene Recyclates. In Proceedings of the ANTEC 2023, Denver, CO, USA, 27–30 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, D.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Chang, Y.; Kim, D.H. Morphological, Thermal, Rheological, and Mechanical Properties of PP/EVOH Blends Compatibilized with PP-g-IA. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2016, 56, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Park, C.; Lee, K.; Nam, J.; Kim, S.W. Rheological, Morphological, Mechanical, and Barrier Properties of PP/EVOH Blends. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2001, 20, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisant, J.B.; Aït-Kadi, A.; Bousmina, M.; Descheˆnes, L. Morphology, Thermomechanical and Barrier Properties of Polypropylene-Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Blends. Polymer 1998, 39, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, P.; Sykutera, D.; Czyżewski, P. Circular Economy of Barrier Packaging Produced in Co-Injection Molding Technology. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 391, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tall, S. Recycling of Mixed Plastic Waste—Is Separation Worthwhile; Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Landinez, J.F.; Salcedo-Galan, F.; Medina-Perilla, J.A. Polypropylene/Ethylene-And Polar-Monomer-Based Copolymers/Montmorillonite Nanocomposites: Morphology, Mechanical Properties, and Oxygen Permeability. Polymers 2021, 13, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisa, N.N.; Setiawan, R.; Wicaksono, D.; Dimas, E. The Effect of Recycling Frequency on the Melt Flow Rate of Polypropylene Materials. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2927, 020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurrekoetxea, J.; Sarrionandia, M.A.; Urrutibeascoa, I.; Maspoch, M.L.L. Effects of Recycling on the Microstructure and the Mechanical Properties of Isotactic Polypropylene. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 2607–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlouli, N.; Pessey, D.; Raveyre, C.; Guillet, J.; Ahzi, S.; Dahoun, A.; Hiver, J.M. Recycling Effects on the Rheological and Thermomechanical Properties of Polypropylene-Based Composites. Mater. Des. 2012, 33, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touil, H.; Pankoke, U.; Schmitz, D.; Bothor, R. Recycling Compatibility of EVOH Barrier Polymers in Polyethylene-Based Packaging Compositions; Institut Cyclos-HTP GmbH: Aachen, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, L.; Leuchtenberger-Engel, L.; Hopmann, C. Enhancing the Quality of Polypropylene Recyclates: Predictive Modelling of the Melt Flow Rate and Shear Viscosity. Polymers 2024, 16, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soarnol. “Ethylene Vinyl Alcohol Copolymer (EVOH)”. February 2024. Available online: https://www.soarnol.com/eng/grade/pdf/dc3212b.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Kuraray EVALTM Highest Level of Gas Barrier Properties of Any Plastic. Available online: https://www.kuraray.com/in-en/products/eval/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Borealis AG. Solutions for Moulding Applications. Available online: https://www.borealisgroup.com/storage/Polyolefins/Consumer-Products/MO-SDS-124-GB-2022-07-BB_Solutions-for-Moulding-Applications.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Traxler, I.; Kaineder, H.; Fischer, J. Simultaneous Modification of Properties Relevant to the Processing and Application of Virgin and Post-Consumer Polypropylene. Polymers 2023, 15, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Velzen, E.U.T.; Chu, S.; Alvarado Chacon, F.; Brouwer, M.T.; Molenveld, K. The Impact of Impurities on the Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polyethylene. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2021, 34, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, W.; Karlsson, S. Assessment of Thermal and Thermo-Oxidative Stability of Multi-Extruded Recycled PP, HDPE and a Blend Thereof. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2002, 78, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenthaler, P.J.; Fischer, J.; Liu, Y.; Lang, R.W. Polypropylene Pipe Compounds with Varying Post-Consumer Packaging Recyclate Content. Polymers 2022, 14, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoian, S.A.; Gabor, A.R.; Albu, A.-M.; Nicolae, C.A.; Raditoiu, V.; Panaitescu, D.M. Recycled Polypropylene with Improved Thermal Stability and Melt Processability. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 2469–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantsev, A.L.; Rodionova, O.Y. Hard and Soft Methods for Prediction of Antioxidants’ Activity Based on the DSC Measurements. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2005, 79, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmizadeh, E.; Tzoganakis, C.; Mekonnen, T.H. Degradation Behavior of Polypropylene during Reprocessing and Its Biocomposites: Thermal and Oxidative Degradation Kinetics. Polymers 2020, 12, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzec, A. The Effect of Dyes, Pigments and Ionic Liquids on the Properties of Elastomer Composites. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-01166530/file/TH2014MarzecAnna.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Li, B.; Li, Y.; Tong, Z.; Yang, H.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z. Thermal Decomposition Reaction Kinetics and Storage Life Prediction of Polyacrylate Pressure-Sensitive Adhesive. e-Polymers 2023, 23, 20220089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, Z.; Pełech, R. The Thermal Degradation of Acrylic Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives Based on Butyl Acrylate and Acrylic Acid. Prog. Org. Coat. 2009, 65, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Kowalczyk, K.; Gruszecki, J.; Idzik, T.J.; Sośnicki, J.G. Thermally Stable UV-Curable Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives Based on Silicon–Acrylate Telomers and Selected Adhesion Promoters. Polymers 2024, 16, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, K.S.; Strangl, M.; Pereira, S.R.; Tiboni, A.R.; Ortner, E.; Spinacé, M.A.S.; Buettner, A. Odor Characterization of Post-Consumer and Recycled Automotive Polypropylene by Different Sensory Evaluation Methods and Instrumental Analysis. Waste Manag. 2020, 115, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, P.; Buettner, A. Sensory Characterization and Identification of Odorous Constituents in Acrylic Adhesives. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 78, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanes, A.; Fullana, A. New Methods to Remove Volatile Organic Compounds from Post-Consumer Plastic Waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 144066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, R.; Wrona, M.; Nerín, C.; Bertochi Veroneze, I.; Gavril, G.-L.; Andrea Cruz, S. Importance of Profile of Volatile and Off-Odors Compounds from Different Recycled Polypropylene Used for Food Applications. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Specimen | Name | Composition | Derived From | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | Label + Adhesive | |||

| 1 | I1 (PP label 1) | 50% | 50% | R1 diluted with R8 |

| 1a * | 75% | 25% | ||

| 1b * | 87.5% | 12.5% | ||

| 1c * | 95% | 5% | ||

| 2 | I2 (PP label 2) | 50% | 50% | R2 diluted with R8 |

| 2a * | 75% | 25% | ||

| 2b * | 87.5% | 12.5% | ||

| 2c * | 95% | 5% | ||

| 3 | I3 (PP label 3) | 50% | 50% | R3 diluted with R8 |

| 3a * | 75% | 25% | ||

| 3b * | 87.5% | 12.5% | ||

| 3c * | 95% | 5% | ||

| PP | EVOH | |||

| 4 | I4 (PP granulate with EVOH) | 90% | 10% | R4 diluted with R8 |

| 4a * | 95% | 5% | ||

| 4b * | 99% | 1% | ||

| 5 | I5 (cPP film with EVOH) | 90% | 10% | R5 diluted with R6 |

| 5a ** | 95% | 5% | ||

| 5b ** | 99% | 1% | ||

| 6 | I6 (cPP film) | 100% PP | R6 | |

| 7 | I7 (cPP film coated with Ormocer®) | 100% PP with Ormocer | R7 | |

| 8 | I8 (PP granulate) | 100% PP | R8 | |

| 9 | I9 (virgin PP granulate) | 100% PP | R9 = virgin PP granulate | |

| Grade of Difference in Odor Intensity | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No perceptible difference in odor |

| 1 | Barely perceptible difference in odor |

| 2 | Mild difference in odor |

| 3 | Noticeable difference in odor |

| 4 | Strong difference in odor |

| Material (Granulate) | MFR (g/10 min) |

|---|---|

| R1 (PP label 1) | 7.1 ± 0.1 |

| R2 (PP label 2) | 6.9 ± 1.4 |

| R3 (PP label 3) | 6.1 ± 0.6 |

| R4 (PP granulate with EVOH) | 6.4 ± 0.1 |

| R5 (cPP film with EVOH) | 5.7 ± 0.0 |

| R6 (cPP film) | 4.4 ± 0.1 |

| R7 (cPP film coated with Ormocer®) | 4.6 ± 0.0 |

| R8 (PP granulate) | 5.9 ± 0.1 |

| virgin PP granulate | 6.2 ± 0.2 |

| Material (Granulate) | Extrapolated Onset Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|

| R1 (PP label 1) | 221 |

| R2 (PP label 2) | 217 |

| R3 (PP label 3) | 221 |

| R4 (PP granulate with EVOH) | 237 |

| R5 (cPP film with EVOH) | 236 |

| R6 (cPP film) | 226 |

| R7 (cPP film coated with Ormocer®) | 224 |

| R8 (PP granulate) | 217 |

| virgin PP granulate | 218 |

| Material (Granulate) | Median of Difference in Odor Intensity |

|---|---|

| R1 (PP label 1) | 3.0 |

| R2 (PP label 2) | 4.0 |

| R3 (PP label 3) | 3.75 |

| R4 (PP granulate with EVOH) | 2.5 |

| R5 (cPP film with EVOH) | 2.25 |

| R6 (cPP film) | 2.0 |

| R7 (cPP film coated with Ormocer®) | 3.5 |

| R8 (PP granulate) | 1.0 |

| virgin PP granulate | 1.0 |

| Test Specimen | Name | Composition | Median of Difference in Odor Intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | Label + Adhesive | |||

| 1 | I1 (PP label 1) | 50% | 50% | 3.5 |

| 1a * | 75% | 25% | 4.0 | |

| 1b * | 87.5% | 12.5% | 3.5 | |

| 1c * | 95% | 5% | 3.0 | |

| 2 | I2 (PP label 2) | 50% | 50% | 4.0 |

| 2a * | 75% | 25% | 4.0 | |

| 2b * | 87.5% | 12.5% | 3.25 | |

| 2c * | 95% | 5% | 3.5 | |

| 3 | I3 (PP label 3) | 50% | 50% | 3.0 |

| 3a * | 75% | 25% | 4.0 | |

| 3b * | 87.5% | 12.5% | 3.5 | |

| 3c * | 95% | 5% | 2.5 | |

| PP | EVOH | |||

| 4 | I4 (PP granulate with EVOH) | 90% | 10% | 4.0 |

| 4a * | 95% | 5% | 2.25 | |

| 4b * | 99% | 1% | 2.25 | |

| 5 | I5 (cPP film with EVOH) | 90% | 10% | 2.5 |

| 5a ** | 95% | 5% | 2.5 | |

| 5b ** | 99% | 1% | 2.75 | |

| 6 | I6 (cPP film) | 100% PP | 2.25 | |

| 7 | I7 (cPP film coated with Ormocer®) | 100% PP with Ormocer® | 3.75 | |

| 8 | I8 (PP granulate) | 100% PP | 2.0 | |

| 9 | I9 (virgin PP granulate) | 100% PP | 1.75 | |

| References | Processing (How Recycling was Simulated) | Properties Studied | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | Twin-screw extruder–counter-rotating | Tensile, TGA, MFI, Impact strength |

|

| [43] | Co-rotating twin-screw extruder | MFR, DSC, Polarized Optical Microscopy, Tensile, GPC, SEM |

|

| [44] | Injection-molding machine; five different compositions of PP/rPP | Tensile, Flexural strength, Bending modulus, SEM |

|

| [45] | Injection-molding machine; multiple recycling cycles | MFI, Thermal behavior, Tensile |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmiedt, R.; Krainz, M.; Tosic, K.; Sharbafian, F.; Krauter, S.; Krauter, V.; Novak, M.; Rainer, B.; Washüttl, M.; Apprich, S. Impact of EVOH, Ormocer® Coating, and Printed Labels on the Recyclability of Polypropylene for Packaging Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243332

Schmiedt R, Krainz M, Tosic K, Sharbafian F, Krauter S, Krauter V, Novak M, Rainer B, Washüttl M, Apprich S. Impact of EVOH, Ormocer® Coating, and Printed Labels on the Recyclability of Polypropylene for Packaging Applications. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243332

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmiedt, Romana, Michael Krainz, Katharina Tosic, Farshad Sharbafian, Simon Krauter, Victoria Krauter, Martin Novak, Bernhard Rainer, Michael Washüttl, and Silvia Apprich. 2025. "Impact of EVOH, Ormocer® Coating, and Printed Labels on the Recyclability of Polypropylene for Packaging Applications" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243332

APA StyleSchmiedt, R., Krainz, M., Tosic, K., Sharbafian, F., Krauter, S., Krauter, V., Novak, M., Rainer, B., Washüttl, M., & Apprich, S. (2025). Impact of EVOH, Ormocer® Coating, and Printed Labels on the Recyclability of Polypropylene for Packaging Applications. Polymers, 17(24), 3332. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243332