Photothermal Heat Transfer in Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Carbon Nanotubes Composites Modeled Through Cellular Automata

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

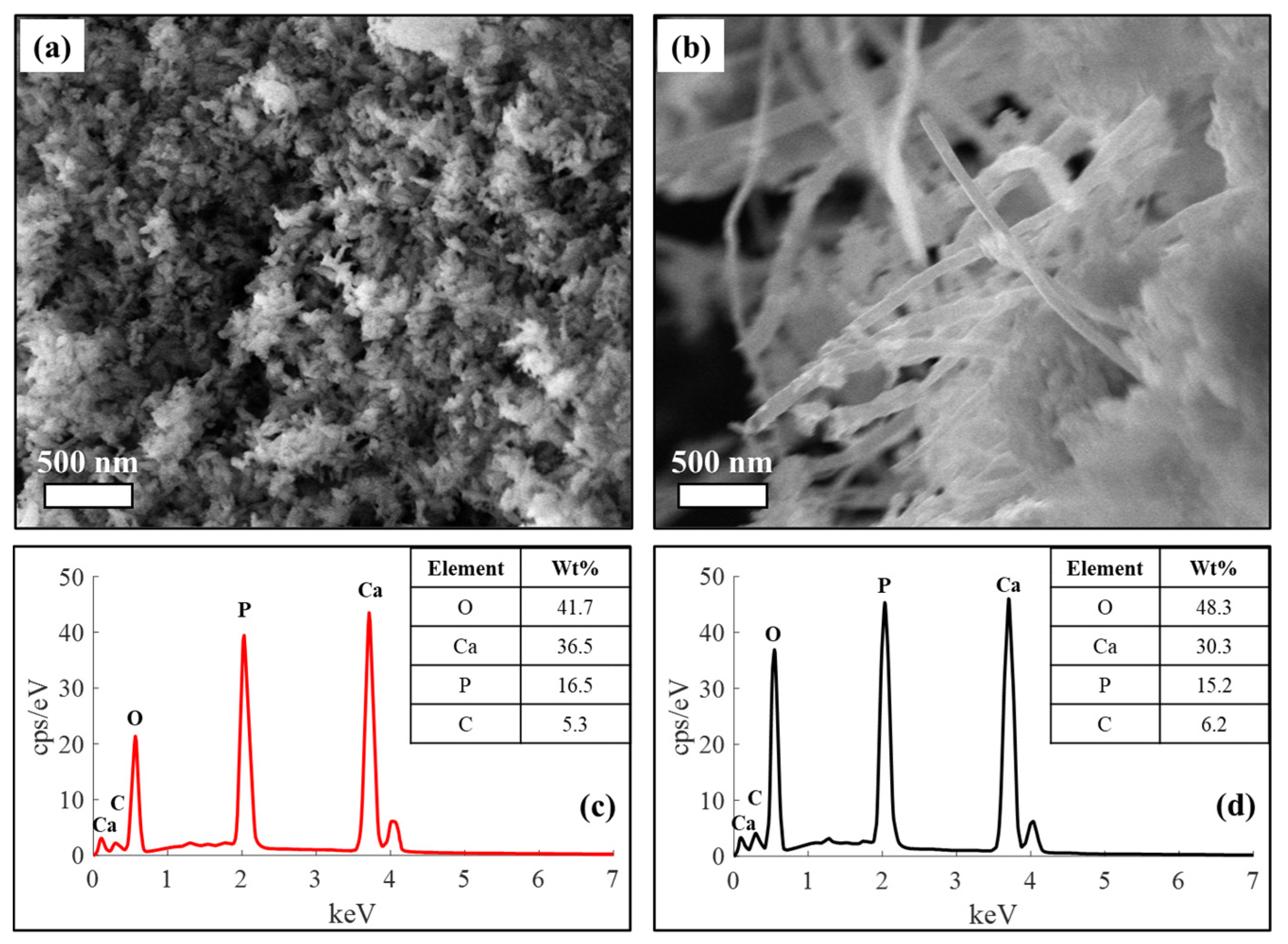

2.1. Nanocomposites Synthesis

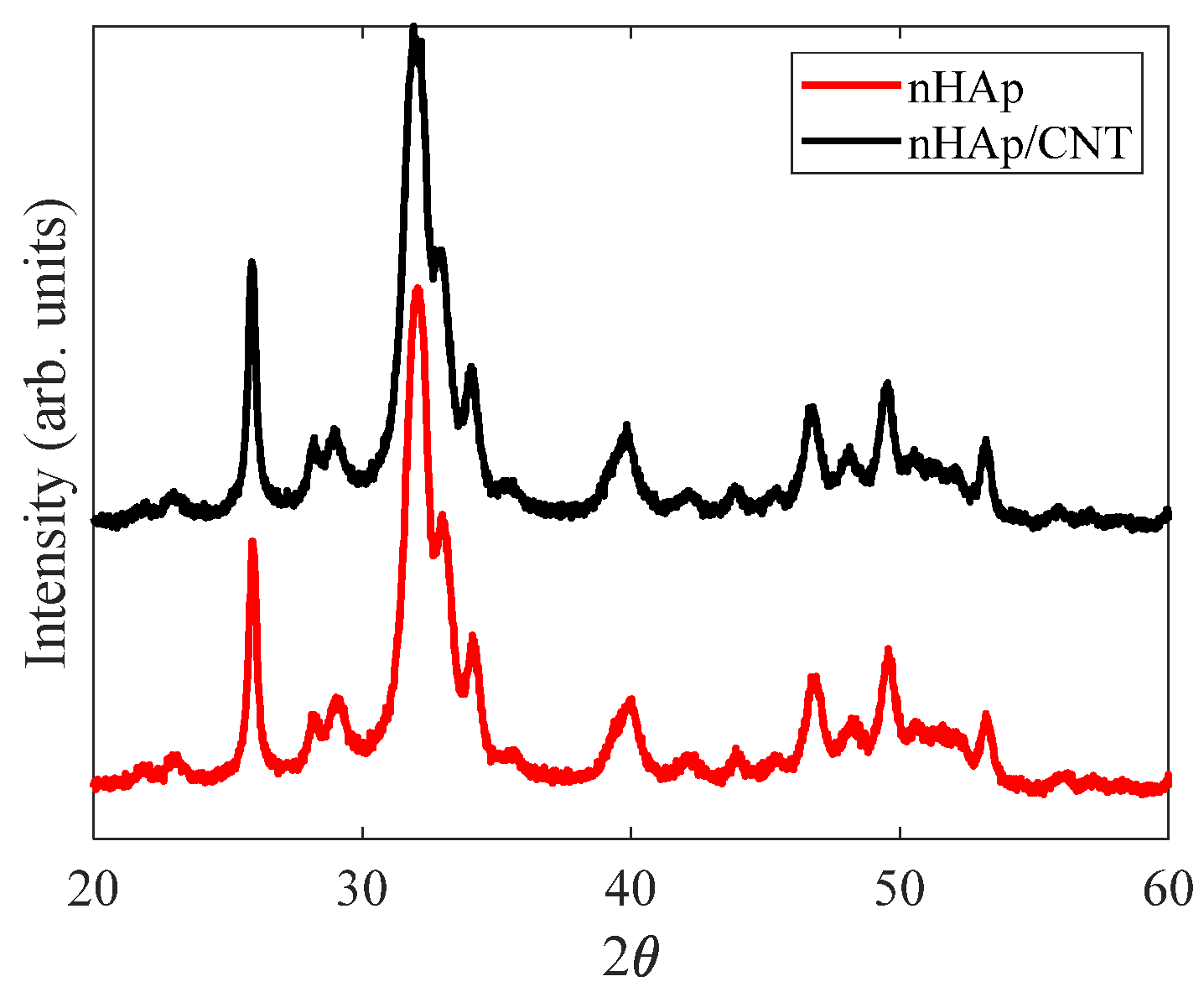

2.2. Characterizations

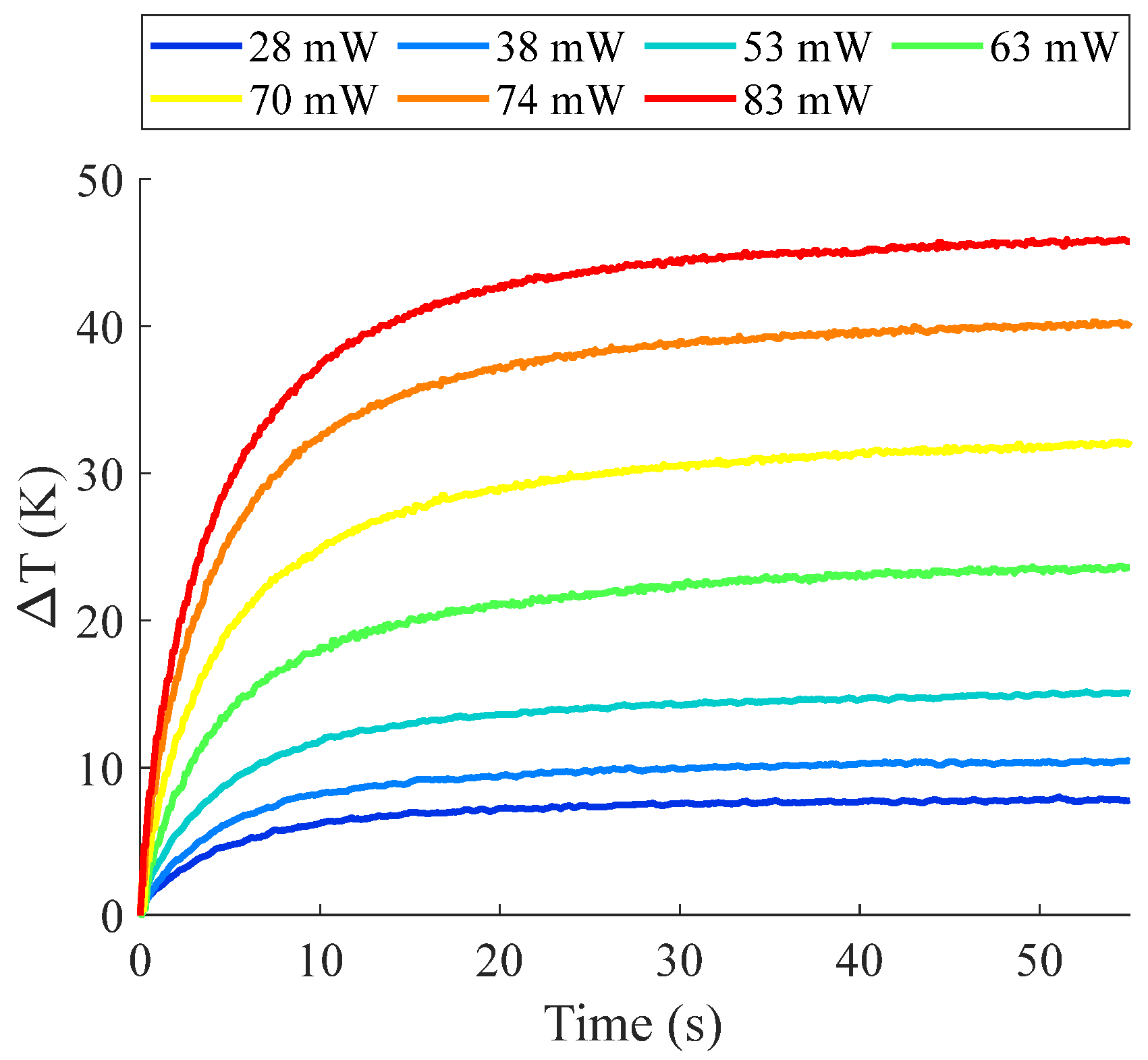

2.3. Photothermal Measurement Methodology

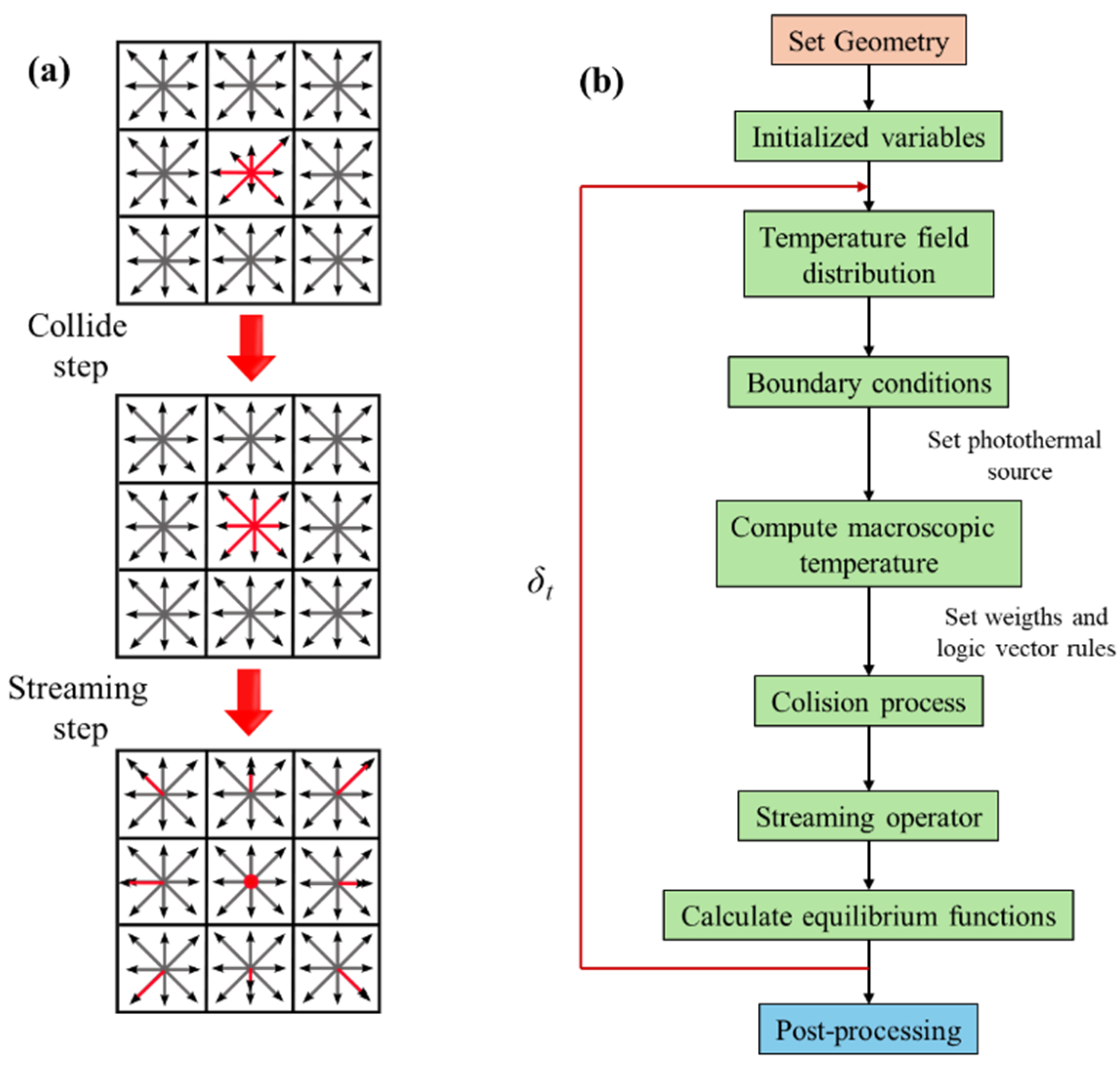

2.4. Cellular Automata Description

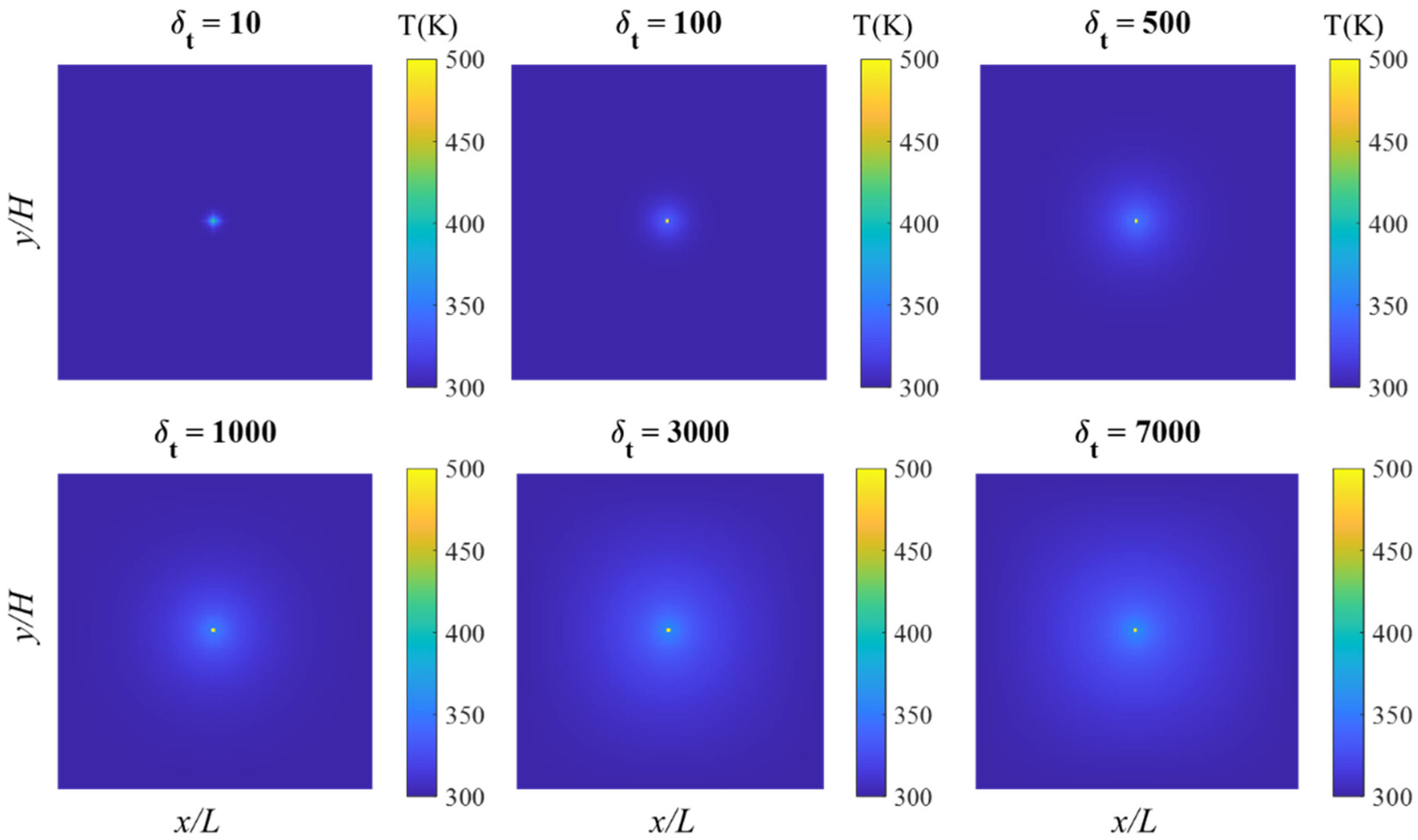

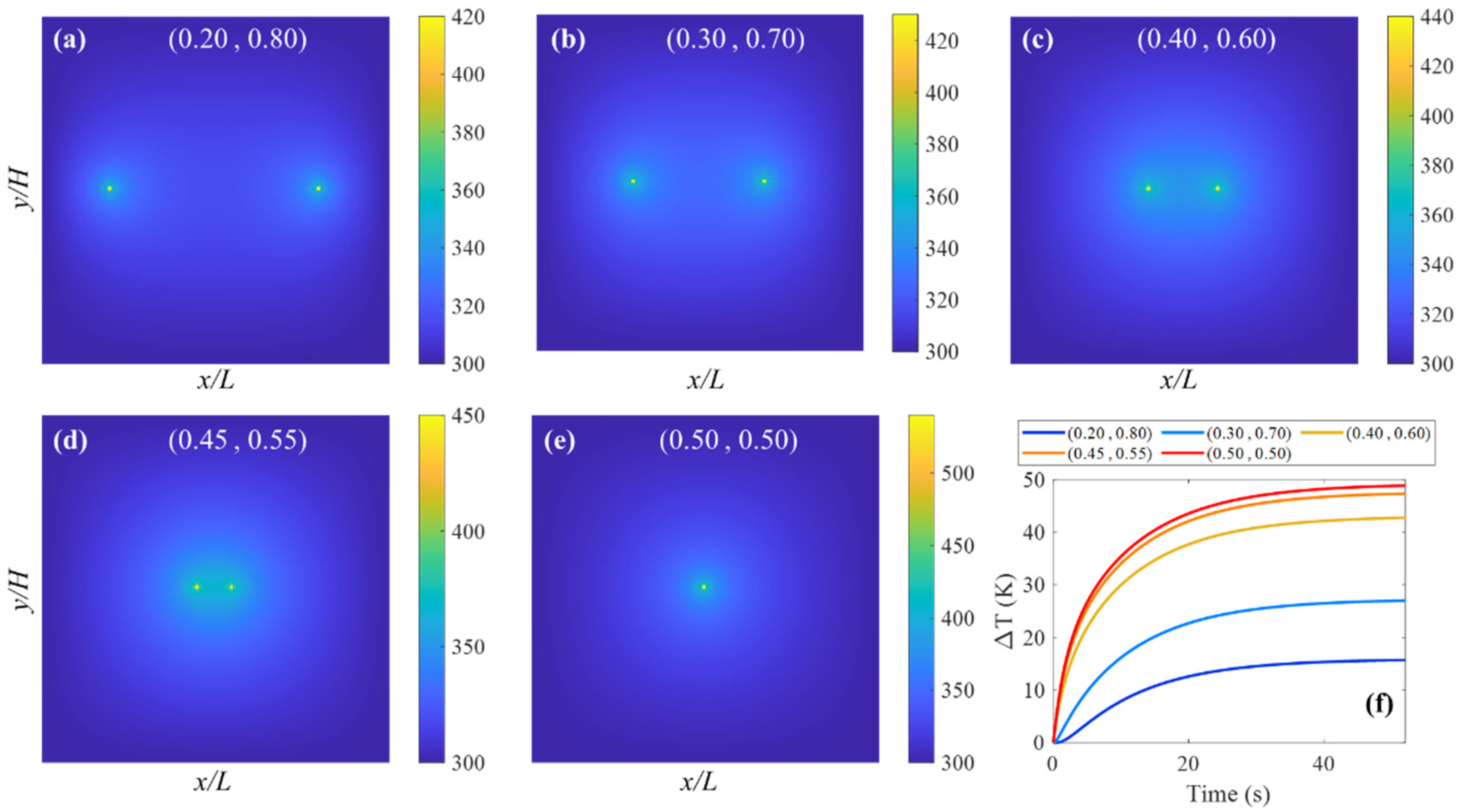

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saurav, S.; Mazumder, S. Extraction of Thermal Conductivity Using Phonon Boltzmann Transport Equation Based Simulation of Frequency Domain Thermo-Reflectance Experiments. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 204, 123871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Merino, J.A.; Jiménez-Marín, E.; Mercado-Zúñiga, C.; Trejo-Valdez, M.; Vargas-García, J.R.; Torres-Torres, C. Quantum and Bistable Magneto-Conductive Signatures in Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes Decorated with Bimetallic Ni and Pt Nanoparticles Driven by Phonons. OSA Contin. 2019, 2, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, G.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, J.; Paik, M.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, M.G.; et al. Perov-skite Solar Cells with Atomically Coherent Interlayers on SnO2 Electrodes. Nature 2021, 598, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Vaghefi Esfidani, S.M.; Lee, J.; Kulkarni, S.P.; Wang, Y.; Hershey, M.; North, J.D.; Aydin, K.; Folland, T.G.; Swearer, D.F. Harnessing Phonon Polaritons for Dynamic and Sensitive Hydrogen Detection in the Mid-Infrared. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 33080–33090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modanlou, S.; Gholami, M. Designing a Time-to-Digital Converter Using Quantum-Dot Cellular Automata Nanotechnology. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Boek, E.S. A Comparison Study of Multi-Component Lattice Boltzmann Models for Flow in Porous Media Applications. Comput. Math. Appl. 2013, 65, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, N.A. Construction of Nonlinear Differential Equations for Description of Propagation Pulses in Optical Fiber. Optik 2019, 192, 162964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-J.; Yu, H.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Chen, A.S. Dynamic-Wave Cellular Automata Framework for Shallow Water Flow Modeling. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, D.C. Nature-Inspired Algorithms and Systems. In Complex Systems and Clouds; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chopard, B. Cellular Automata and Lattice Boltzmann Modeling of Physical Systems. In Handbook of Natural Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 287–331. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, C.; Vieira, T.; Silva, J.C.; Borges, J.P.M.R.; Lança, M.C. Bioactive Hydroxyapatite Aerogels with Pie-zoelectric Particles. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloshchapov, D.L.; Lenshin, A.S.; Savchenko, D.V.; Seredin, P.V. Importance of Defect Nanocrystalline Cal-cium Hydroxyapatite Characteristics for Developing the Dental Biomimetic Composites. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Wang, M.; Lv, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, F.; Liang, Z.; Huang, D.; Wei, X.; Chen, W. Carbon Nano-tubes-Reinforced Polylactic Acid/Hydroxyapatite Porous Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Front. Mater. Sci. 2024, 18, 240675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, W.; Zhu, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, X. Photobiomodulation Therapy at 650 Nm Enhances Osteogenic Differentiation of Osteoporotic Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells through Modulating Autophagy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 50, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, D.; Karamitaheri, H.; de Sousa Oliveira, L.; Neophytou, N. Effect of Wave versus Particle Pho-non Nature in Thermal Transport through Nanostructures. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2020, 180, 109712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Merino, J.A.; Barmavatu, P.; Viswanathan, M.R.; Nandi, S.; Sikarwar, V.S.; Mercado-Zúñiga, C. Optically Induced Nonlinear Piezoelectric Response in Nano-Hydroxyapatite Ceramics for Biotechnological Applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 64243–64253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, V. Synthesis and Characterization of Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Hydroxyap-atite Ceramics Proposed for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, M. Lattice Boltzmann Modeling of Phonon Transport. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 315, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Bungartz, H.-J.; Mehl, M.; Neckel, T.; Weinzierl, T. A Coupled Approach for Fluid Dynamic Problems Using the PDE Framework Peano. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2012, 12, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, H.; Sellier, M. Modeling an Impact Droplet on a Pair of Pillars. Interfacial Phenom. Heat. Transf. 2017, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- García-Merino, J.A.; Villarroel, R.; Mercado-Zúñiga, C.; Morales-Bonilla, S. Coatings Based on Hybrid Car-bon-Platinum Nano-Ink for Multifunctional Applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1022, 180132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, C.; Lian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, T.; Hu, X. Understanding the Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups on Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes toward Supercapacitors. Mater. Today Chem. 2021, 19, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Injorhor, P.; Trongsatitkul, T.; Wittayakun, J.; Ruksakulpiwat, C.; Ruksakulpiwat, Y. Nano-Hydroxyapatite from White Seabass Scales as a Bio-Filler in Polylactic Acid Biocomposite: Preparation and Characterization. Polymers 2022, 14, 4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Li, M.; Xie, T.; Gu, Z. Lattice Boltzmann Method for Conduction and Radiation Heat Transfer in Composite Materials. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 31, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, T.; Tomar, V. An Analysis of the Effects of Temperature and Structural Arrangements on the Thermal Conductivity and Thermal Diffusivity of Tropocollagen–Hydroxyapatite Interfaces. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 38, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Merino, J.A.; Mercado-Zúñiga, C.; Martínez-González, C.L.; Torres-SanMiguel, C.R.; Vargas-García, J.R.; Torres-Torres, C. Magneto-Conductive Encryption Assisted by Third-Order Nonlinear Optical Effects in Carbon/Metal Nanohybrids. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 035601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jin, W.; Ren, W. Dual-Comb Photothermal Spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, H. Advances in the Application of Photothermal Composite Scaffolds for Osteosarcoma Ablation and Bone Regeneration. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 46362–46375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Zhou, D.; Wang, F.; Li, G.; Bai, L.; Su, J. Programmable Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 29, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X. The Utilization of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Bone Tissue Regeneration and Engineering: Respective Featured Applications and Future Prospects. Med. Nov. Technol. Devices 2022, 16, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, H. Analysis of Temperature Behavior in Biological Tissue in Photothermal Therapy According to Laser Irradiation Angle. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 2252668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wu, J.; Gu, X.; Yang, L. High-Order Flux Reconstruction Thermal Lattice Boltzmann Flux Solver for Simulation of Incompressible Thermal Flows. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 106, 035301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikin, D.; Zakharchuk, K.; Xie, W.; Romanyuk, K.; Pereira, M.J.; Arias-Serrano, B.I.; Weidenkaff, A.; Kholkin, A.; Kovalevsky, A.V.; Tselev, A. Quantitative Characterization of Local Thermal Properties in Thermoelec-tric Ceramics Using “Jumping-Mode” Scanning Thermal Microscopy. Small Methods 2023, 7, e2201516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yan, Y.; Qi, H. Photothermal Conversion and Transfer in Photothermal Therapy: From Macroscale to Nanoscale. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2022, 308, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Hyun, Y.-T.; Won, J.W.; Lee, H.; Kang, S.-H.; Yoon, J. Numerical Simulation Using a Coupled Lattice Boltzmann–Cellular Automata Method to Predict the Microstructure of Ti–6Al–4V after Electron Beam Cold Hearth Melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 3796–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łach, Ł.; Svyetlichnyy, D. New Platforms Based on Frontal Cellular Automata and Lattice Boltzmann Meth-od for Modeling the Forming and Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2022, 15, 7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Laser Power (mW) | Experimental Tmax (K) | CA Tpulse (K) | NRMSE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | 302.05 | 347 | 1.93 | 0.991 |

| 38 | 305.17 | 362 | 1.64 | 0.992 |

| 53 | 309.65 | 390 | 1.40 | 0.994 |

| 63 | 317.95 | 440 | 1.28 | 0.996 |

| 70 | 326.49 | 492 | 1.22 | 0.996 |

| 74 | 334.67 | 543 | 1.91 | 0.992 |

| 83 | 340.47 | 576 | 2.25 | 0.992 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mercado-Zúñiga, C.; García-Merino, J.A. Photothermal Heat Transfer in Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Carbon Nanotubes Composites Modeled Through Cellular Automata. Crystals 2025, 15, 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121062

Mercado-Zúñiga C, García-Merino JA. Photothermal Heat Transfer in Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Carbon Nanotubes Composites Modeled Through Cellular Automata. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121062

Chicago/Turabian StyleMercado-Zúñiga, Cecilia, and José Antonio García-Merino. 2025. "Photothermal Heat Transfer in Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Carbon Nanotubes Composites Modeled Through Cellular Automata" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121062

APA StyleMercado-Zúñiga, C., & García-Merino, J. A. (2025). Photothermal Heat Transfer in Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Carbon Nanotubes Composites Modeled Through Cellular Automata. Crystals, 15(12), 1062. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121062