1. Introduction

Germanium (Ge) is one of the main materials of modern electronics [

1]. Many physical phenomena in semiconductors were first studied in this material. Germanium is widely used for optical applications in the infrared (IR) region of the spectrum. The advantages of germanium appear when it is used in atmospheric transparency windows of 3–5 and 7–14 microns, which makes it possible to manufacture optoelectronic devices, such as IR cameras, IR thermal imagers, IR sights, etc. In addition to its work in active devices and use in detection structures, germanium has a use as an optical material in spectral devices for the manufacture of IR lenses, prisms, and optical windows [

2].

Studies of the optical properties of Ge were mainly carried out in the IR region of the spectrum where the characteristics of germanium are already well known [

3,

4,

5], while these in the terahertz region (10–0.1 THz, 30–3000 microns) have so far been studied much less. There are only several papers on this subject [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Optical spectra of germanium at the photon energy lower than the band gap are determined by the light interaction with the band gap energy states, phonons, and free charge carriers—electrons and holes. The interaction of radiation with germanium is characterized by the refractive index n, dielectric constant ε, extinction coefficient k, absorption coefficient α, conductivity σ, and other material constants. Knowledge of these constants makes it possible to describe the propagation of electromagnetic radiation in a material medium.

The study of the optical properties of germanium in the terahertz spectral range is based on measuring the reflection and transmission spectra of Ge plates of different thicknesses [

8,

9,

11]. The absorption coefficient spectra α were obtained in the wavelength range of 60–1500 μm [

8] for germanium plates with five different levels of antimony doping. The absorption coefficient increases in the range of 200–1500 μm. The refractive index spectra of Ge were studied in the range of 39–71 μm (4.2–7.7 THz) in the temperature range of 4–296 K [

10]. The refractive index increases with increasing temperature. Real permittivity of Ge increases with increasing temperature: from 15 to 16.3 in the range of 4–350 K. Excitation of the Ge surface with femtosecond optical pulses generates THz pulses [

13]. The amplitude of THz pulses depends on the angle between the optical field vector and crystalline axes. Arsenic donor in Ge was investigated with a time-domain spectroscopy [

14]. The decay time of excited states was found to be 0.8 ns and 0.6 ns. The THz radiation, in the range of 0.36–2.67 THz, both creates free holes through photoionization of Ga and induces the cyclotron resonance of these holes at Ga-doped germanium [

15].

Free-carrier absorption on free charge carriers at a wavelength range greater than 200 μm manifestly depends on the carrier concentration. Note that absorption is possible both on free electrons and on free holes, and the absorption coefficient [

16] is

where

L(λ) describes the interaction of radiation with phonons (lattice absorption) [

17,

18]. The terms

Ah(λ)p and

Ae(λ)n describe the free-carrier absorption where

p and

n are the concentrations of free holes and electrons while

Ah and

Ae are the corresponding cross-sections. It was found [

16] that at 10.6 µm wavelength,

Ah = 5.33 × 10

−16 cm

2 and

Ae = 0.34 × 10

−16 cm

2.

The optical properties of germanium and its application in photonics are described in [

19]. The electrical properties of germanium are described in [

20].

Broadband THz emissions up to 8 THz from pure bulk Ge under 100 fs optical pulses around 1590 nm were observed [

21]. Radiation in the terahertz frequency range is revealed in p-Ge in crossed strong electric and magnetic fields [

22].

Germanium optical windows protect the photodetector from atmospheric influences and provide transmission of IR radiation and screening from external electromagnetic fields [

6,

7]. The efficiency of this screening depends on the concentration of free carriers [

6].

We investigated a set of eleven samples with different carrier concentrations. In order to determine the dependence of transmission, reflection, absorption, and optical parameters of the samples on their doping level, a set of samples with a donor impurity concentration of 2.46 × 1013–9.1 × 1014 cm−3 was investigated. Antimony was used as an impurity, since it is often used by manufacturers of germanium plates to obtain n-type doping.

2. Materials and Methods

To study the interaction of terahertz radiation with single-crystalline germanium at room temperature, we used Sb-doped n-type Ge blanks with a diameter of 50 mm and a thickness of 3 mm, manufactured by Vital Advanced Materials Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China, and polished them on both sides by Tydex, LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia. The resulting plates had orientation (100). Eleven plates with room temperature resistivities ranging from 1.45 to 49.88 Ohm·cm were studied. The parameters of the germanium plates are shown in

Table 1. This range of resistivity values was chosen because it covers all applications of germanium in optics, including optical windows and lenses and electromagnetic shielding. The donor concentration

Nd for the average resistivity in the intervals given in

Table 1 varied from 2.46 × 10

13 cm

−3 to 9.1 × 10

14 cm

−3, where the lowest value is close to the intrinsic concentration in Ge at room temperature.

Spectral measurements of germanium plates were performed at room temperature on a Bruker Vertex 70 Fourier spectrometer, Ettlingen, Germany in the range of 1.5–670 µm and on a Menlo Systems TERA K8 time-domain terahertz spectrometer, Planegg, Germany [

23] in the range of 200–3000 µm. The experimental methodology is described in detail in [

23,

24].

2.1. Spectral Measurement on Bruker Vertex 70

For the standard measurements on the Vertex 70, the spectral resolution for the MIR range is set to 8 cm−1, for the FIR range is set to 4 cm−1 and for the FFIR range is set to 2 cm−1. A globar lamp is used as a source of MIR and FIR radiation. For the far FFIR wavelength range (up to 670 µm), a continuous spectrum of mercury arc lamp radiation is used. The spectrometer is equipped with a detector with a built-in preamplifier, operating without cooling at the room temperature. The device has a set of additional attachments to measure transmission in a collimated beam and specular reflection at a minimum fixed beam incidence angle of 11 degrees.

When measuring the sample transmission, the void channel interferogram measured as reference. The optical transmittance measurements were made at a normal incidence of radiation. When measuring reflectivity, a gold mirror was used as a reference. As a result of the inverse Fourier transform of these interferograms, the spectrum of sample and reference signal are restored. By dividing the first spectrum by the second, the transmission or reflection spectrum of the sample is determined. The reflectance result signal is then multiplied by the reference gold mirror.

2.2. Spectral Measurement on TERA K8

The time-domain spectroscopy method is based on the coherent detection of the terahertz radiation pulse waveform transmitted or reflected from the sample under study. Such pulse waveform provides information about amplitude and signal phase. To generate and detect the broadband THz radiation, the TERA8-1 LT-GaAs semiconductor antennas excited by a femtosecond laser 780 nm are used.

In the case of measuring the transmission spectrum of a sample, the radiating and receiving antennas are located in line. The linearly polarized THz radiation is focused into the minimum aperture at the sample location and transmits the maximum power from the radiating antenna to the receiving antenna at normal incidence. In the case of measuring the reflection spectrum, the sample is placed at the focal point at an angle of 12 degrees to the incident radiation. Thus, the reflection measurement from the sample is performed at an angle of 12 degrees relative to the normal line to the sample surface.

The time dependences of the receiving antenna photocurrent are measured using the K8 TeraScan Mark II 1.32 software. In the case of transmission signal measurement, the waveform of the void channel was taken as the reference spectrum. In the case of the reflection signal measurements, the pulse waveform reflection from a mirror with a gold coating is measured as a reference and the mirror is set in the same position as the measured sample. The inverse Fourier transform of the measured reference and sample temporal waveforms is performed using the TeraMat program. The magnitude and phase of the complex transmission function were found.

The hole concentration

p0 for the average resistivity value in the intervals given in

Table 1 is calculated using formula [

1]

where

ni is the intrinsic concentration and

n0 =

ni +

Nd is the free electron concentration. The donor concentration

Nd was determined from the experimental dependencies of resistivity on the donor concentration [

20,

25]. The plasma frequency of electrons

ωpn and holes

ωpp were calculated [

26] as

where

ε0 is the permittivity of vacuum,

εL is the dielectric constant of the semiconductor and

mn and

mp are the effective masses of electrons and holes.

Calculation of the refractive index

n, extinction coefficient

k and absorption coefficient α in the region of 200–3000 μm based on experimental measurements were carried out using the TeraLyzer Data Extraction Software 1.0 package. The measurement includes at least one echo pulse within the measured time window. The quantity α is related to

k as

3. Results and Discussions

We calculated the optical constants of germanium using experimental transmission and reflection spectra. The transmission spectra are shown in

Figure 1. In the spectral range 1.88–11.5 µm there is a transparency window. This is consistent with the results of [

27,

28]. For a 3 mm plate, the transmittance is 0.46–0.47. Calculation of the refractive index in this spectral region gives the values

n = 4.03 ± 0.03. These data are consistent with previously published results [

10]. This spectral range is used to make IR lenses, prisms, and optical windows.

The phonon absorption spectra were observed in the spectral range 11.5–300 µm. Since single-phonon absorption in germanium is prohibited, the transmission spectra clearly show absorption peaks related to various combinations of two phonons. These phonon combinations can be found in [

3,

4,

16,

17,

18]. Free carrier absorption clearly manifests itself in the spectral range of 200–3000 µm. It occurs also both in the region of the transparency window and in the region of phonon absorption and overlaps with them, but at the existing free carrier concentrations of free carriers makes a small contribution to the wavelengths less than 200 μm. Transmission in the region of free carrier absorption decreases with the increase in donor concentration.

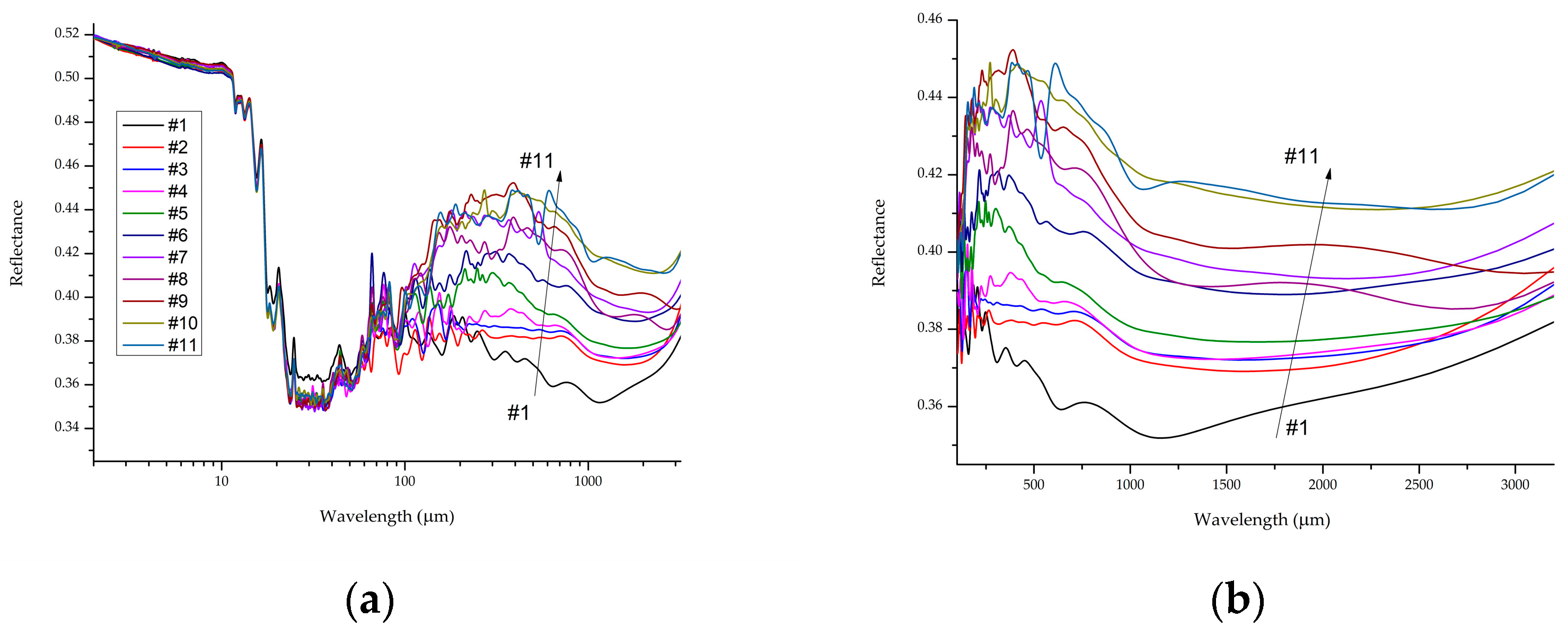

The experimental reflection spectra of the plates are shown in

Figure 2.

The reflectance spectra of the plates clearly show a dependence of the reflectance on the donor concentration (

Figure 2b). The reflection increases from sample #1 to sample #11, i.e., with a decrease in the donor concentration and, consequently, the concentration of free electrons. The reason for this dependence is multiple reflections from the germanium–air interfaces. The absorption coefficient α depends on the concentration of carriers—the higher the concentration, the greater the absorption. Therefore, the intensity of echo pulses depends on the absorption in the germanium plate. In plates with a higher concentration of free carriers, the intensity of echo pulses is lower.

From the given spectra it follows that in plates the reflection increases at wavelengths growth. This is due to the presence of plasma resonance (see

Table 1). At wavelengths exceeding the plasma resonance wavelength

λpn, reflection can increase up to 90% due to the formation of plasma waves [

29,

30]. For samples #1 and #2, the plasma resonance wavelengths are located directly in the measured region. For sample #3, it is close to it. The increase in reflection from plates #10 and #11 at long wavelengths (more than 2500 μm) may be associated with the plasma resonance of electron-hole pairs. The plasma frequency of pairs can exceed that calculated by Formula (2) by approximately 1.5 times [

31,

32]. The Formula (2) is derived at assumption of oscillations of electrons (or holes) relative motionless impurity atoms. When oscillations take place at electron-hole plasma then both electrons and holes are movable, and Formula (2) is inapplicable, so we have to use the results of [

31,

32]. The role of electron-hole pair oscillations will be greater at a low concentration of free electrons, when the number of free holes is greater. Samples #10 and #11 have more oscillating pairs than other samples.

Combinational phonon absorption in the range of 11.5–70 µm weakly depends on the germanium doping level.

As follows from the equations given in [

33,

34] within a bipolar carrier model, the real part of the dielectric constant is

and its imaginary part is

where <

τn> and <

τp> are the energy averaged mean free time of electrons and holes.

Γ11,

Γ12,

Γ21 and

Γ22 are correction functions.

Based on

ε1 and

ε2, model values of

n,

k and

α were calculated. At this case, the value of the momentum relaxation time, determined from the table values of electron and holes mobility, is taken as <

τn> and <

τp>, and

Γ11,

Γ12,

Γ21 and

Γ22 are taken equal to 1. If we take into account that in Ge, the typical mobility of electrons at room temperature is 3900 cm

2/V·s and the mobility of holes is 1900 cm

2/V·s [

20], then we obtain an average mean free time for electrons of 2.7 × 10

−13 s and that for holes of 2.3 × 10

−13 s. The effective masses of the electrons is taken as 0.12m

0 and that of holes as 0.21m

0 [

12]. m

0 is the mass of free electron. Using bipolar carrier model, we are taking into account the influence of electrons and holes on the dielectric constant. The damping term is taken into account by introducing the average mean free time of electrons and holes, which are obtained on the basis of typical values of mobility and values of the effective masses of electrons and holes in germanium [

12].

The refractive index and extinction coefficient are defined as

Figure 3 shows the refractive index spectra calculated on the basis of experimental dependences (

Figure 3a) using the TeraLyzer Data Extraction Software package and model calculations with Formula (7) (

Figure 3b). One can see the qualitative resemblance of these spectra. Some difference may be due to the use of simplified relaxation times and correction functions in the calculations.

The refractive index decreases with increasing doping level. The reason for this dependence is the influence of free carriers on the dielectric constant, since free carriers in the external field of the light wave are redistributed and partially screen this field, changing the value of the polarization vector [

28,

29,

30]. This result follows from the Drude–Lorentz equation. The donors themselves can also influence the polarization vector due to the difference in the polarizability of impurity atoms from the polarizability of atoms of the main material. But, at the values of donor concentration in the studied samples, this effect can be neglected, since the maximum donor concentration in the samples is ~ 10

15 cm

−3, and the density of germanium atoms is 4.45 × 10

22 cm

−3. The refractive index in the wavelength range of 37–75 μm is close to that obtained in [

10].

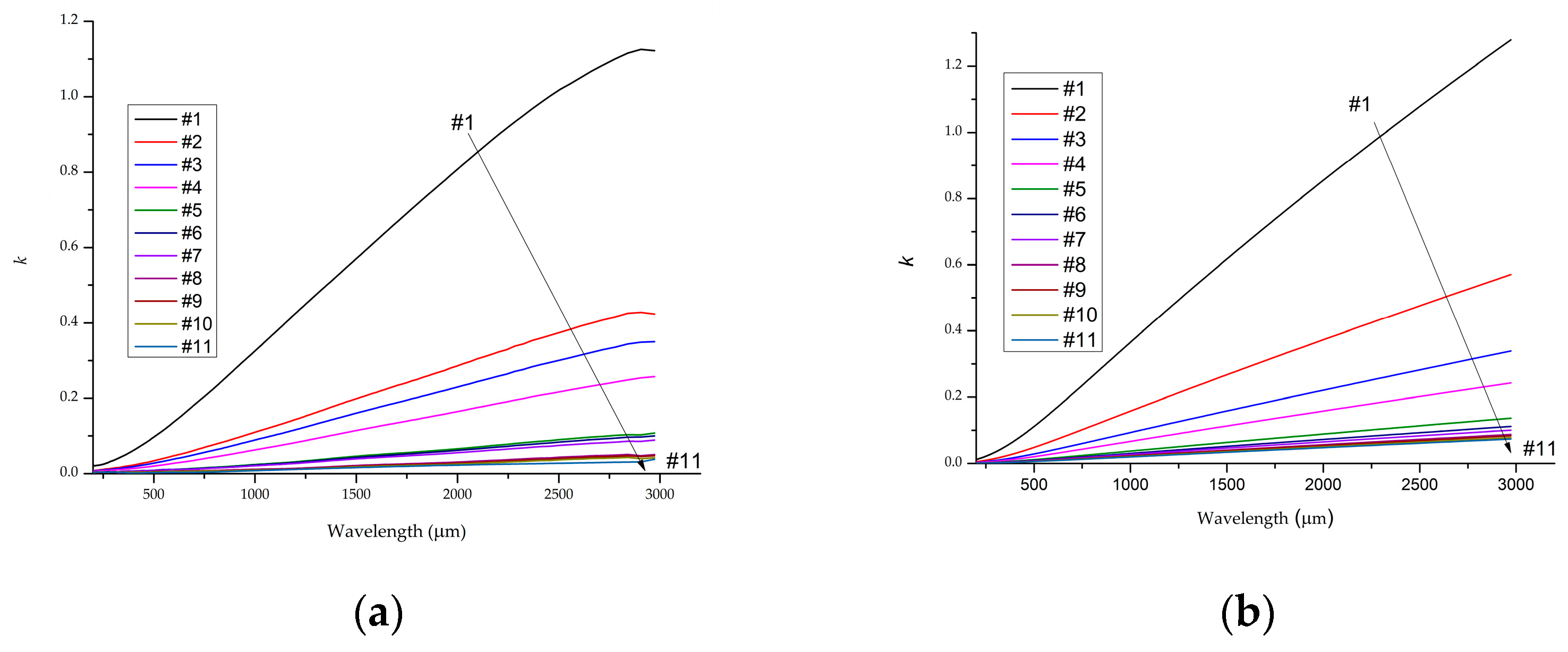

Figure 4 shows the wavelength dependences of the experimental and model calculation of the extinction coefficient. It was calculated on the basis of experimental dependences (

Figure 4a) using the TeraLyzer Data Extraction Software package and model calculations with Formula (8) (

Figure 4b). They demonstrate qualitative agreement. The extinction coefficient (

Figure 4a) increases both with increasing wavelength and with increasing doping level. This behavior is consistent with model calculations using Formula (8) (

Figure 4b).

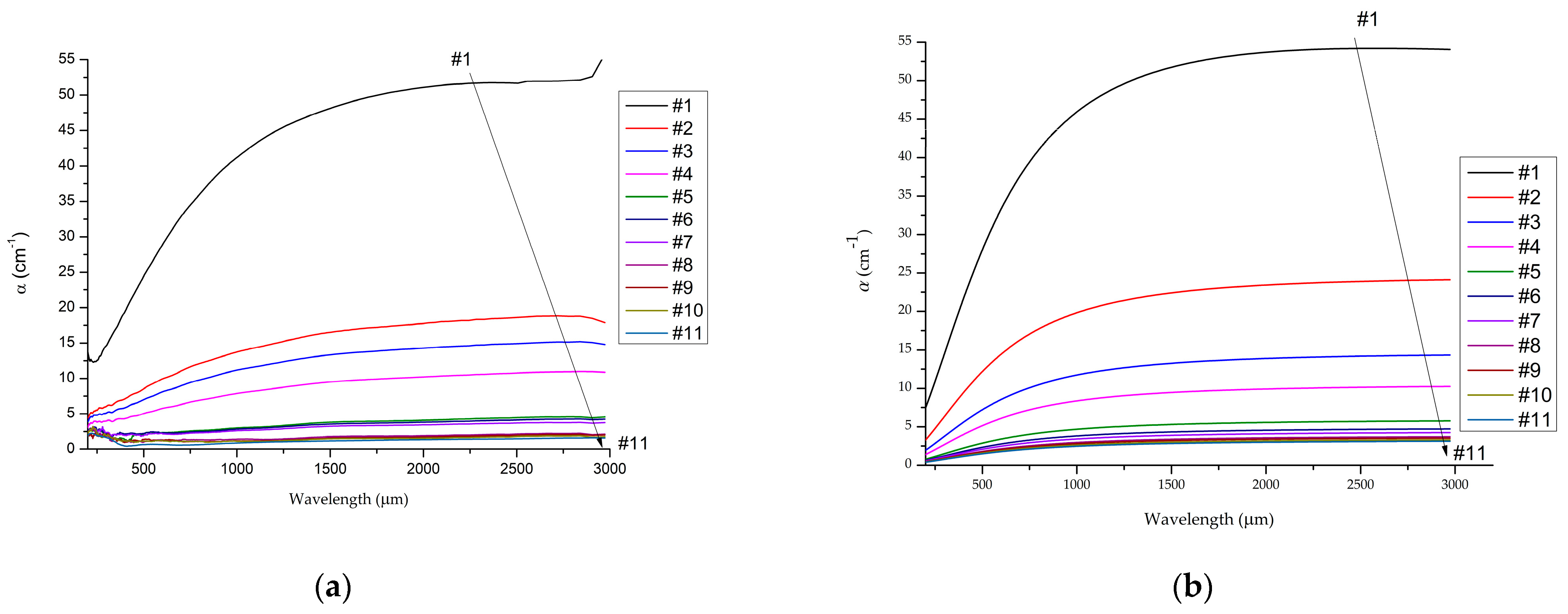

The results of experimental and model calculations of the absorption coefficient α are shown in

Figure 5. These calculations are made using Formula (4), based on the data in

Figure 4.

The absorption coefficient is a complex function of frequency. The peculiarity of the range 200–3000 microns is due to its intermediate position between the high-frequency and low-frequency limits. The dielectric constant (Formulas (5) and (6)) in the presence of free electrons contains the factor 1/(1 + ω

2 τ

2), where ω is the angular frequency of electromagnetic radiation and τ is the average mean free time of electrons or holes. This factor is included in both the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric constant [

35,

36]. Mean free time was used for electrons of 2.7 × 10

−13 s and for holes of 2.3 × 10

−13 s. In the IR region of the spectrum ω

2τ

2 >> 1 and α ~ ω

−2 ~ λ

2, which corresponds to the Drude—Lorentz model [

33]. But in the terahertz range, ω

2τ

2 is approximately 6.25 at a wavelength of 200 μm and 0.03 at a wavelength of 3000 μm. As a result, this leads to a dependence of the absorption coefficient on the wavelength in the range of 200–1800 µm, where ω

2τ

2 > 1, and the absence of such a dependence at the wavelength values greater than 1800 µm, where ω

2τ

2 << 1. Thus, free carrier absorption changes at the high-frequency terahertz range and is independent of wavelength as it approaches 3000 μm. As can be seen from

Figure 5a, the light absorption increases in the range of 200–1800 µm, and then, up to 3000 µm, does not depend on the wavelength.