Photocatalysis and Electro-Oxidation for PFAS Degradation: Mechanisms, Performance, and Energy Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods for PFASs Removal

2.1. Conventional Wastewater Treatment Methods

2.2. Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs)

2.2.1. Heterogeneous Photocatalysis

- Light absorption and electron–hole pair generation: When a semiconductor photocatalyst is irradiated with photons (hν) of energy equal to or greater than its band gap (Eg), an electron (e−) is promoted from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). This process leaves behind a positively charged “hole” (h+) in the valence band, creating an electron–hole pair.

- Charge carrier separation and migration: The photogenerated electrons and holes must separate and migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst. The efficiency of this step is critical, as many electron–hole pairs tend to quickly recombine, releasing their energy as heat or light and reducing the overall efficiency [32].

- Surface Reactions: Once the charge carriers reach the surface, they drive redox reactions: holes act as strong oxidants, either directly attacking adsorbed molecules or reacting with water generating hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (Equation (1)), while electrons typically reduce molecular oxygen to form superoxide radicals (•O2−) or other reactive species (Equation (2)).

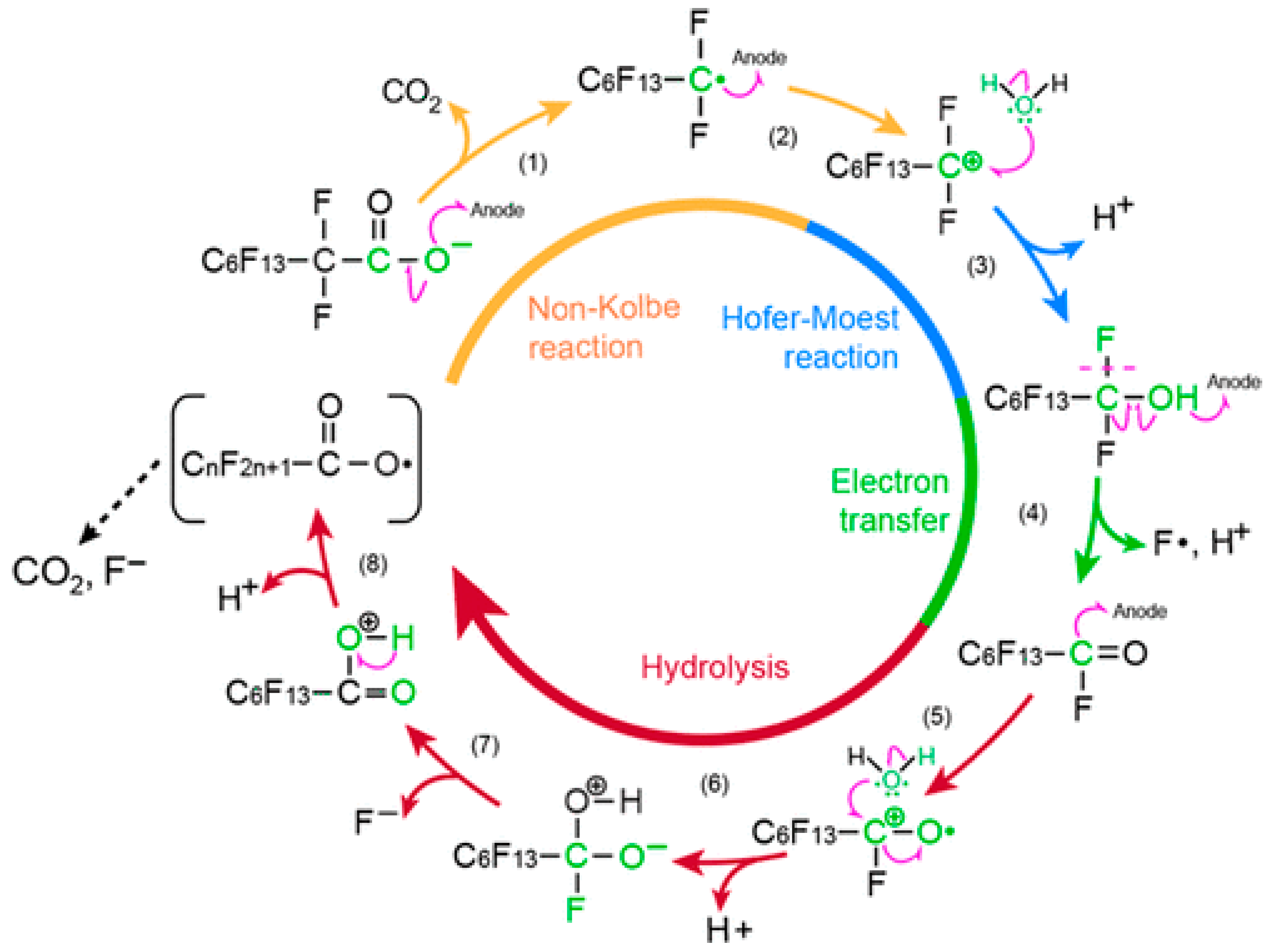

2.2.2. Electrochemical Oxidation (EO)

- Surface doping with functional species, aimed at optimizing the crystalline phase and increasing particle compactness, which enhances the ability of the anode to generate surface-adsorbed reactive oxygen species.

- Metal doping, which can improve electron transfer kinetics.

- Construction of three-dimensional nanostructures, capable of increasing the number of active sites and thereby improving mass transfer and adsorption efficiency.

- Introduction of functional interlayers, which strengthen the adhesion between the active layer and the substrate, resulting in improved anode stability [66].

- Boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrodes are among the most widely studied materials. They possess a wide potential window, high oxidation potential (around 2.7 V vs. SHE), excellent chemical stability, rapid charge-transfer kinetics, and minimal adsorption of intermediates. These features allow BDD to achieve high mineralization rates. However, the high cost of fabrication and the challenges of scaling up production hinder large-scale applications [67].

- Among metal oxides-based electrodes, SnO2-based ones are semiconductors with a wide bandgap, whose conductivity and performance can be significantly improved through doping. Nevertheless, SnO2 electrodes may suffer from short operational lifetimes if not properly modified, and the presence of sulfate ions in the electrolyte can block active sites, lowering hydroxyl radical generation [66]. PbO2-based electrodes are low-cost and simple to fabricate, with high conductivity. Their main drawback lies in the risk of Pb2+ leaching. Also in this case, doping can improve electrode stability, increase electroactive surface area, and mitigate Pb release, but concerns remain regarding their safe long-term application [66].

- Magnéli-phase Ti oxides are sub-stoichiometric titanium oxides that combine high electrical conductivity, good chemical stability, and relatively low production cost, since TiO2 is a cheap precursor. Materials such as Ti4O7 exhibit excellent stability in aggressive electrolytes, and large electroactive surface area. However, long-term stability issues may arise due to the presence of Ti3+ species, and conductivity decreases for higher values of n in TinO2n−1 [68].

3. Evaluation of Energy Efficiency Across Photocatalytic and Electrochemical Treatments

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFAS | Per and polyalkyl substances |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plants |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| PFBS | Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| MCL | Maximum Contaminants Levels |

| PFNA | Perfluoroonanoic acid |

| PFHxS | Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid |

| PFHxA | Perfluorohexanoic acid |

| HFPO-DA | Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid |

| POP | Persistent Organic Pollutants |

| AOP | Advanced Oxidation Processes |

| NF | Nanofiltration |

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| VB | Valence band |

| CB | Conduction band |

| rGO | Reduced Graphene Oxide |

| TNT | Titanium Nanotubes |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Framework |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| EO | Electro-Oxidation |

| BDD | Boron-Doped Diamond |

| FTCA | Fluorotelomer Carboxylic Acids |

| REM | Reactive Electrochemical Membrane |

References

- Sunderland, E.M.; Hu, X.C.; Dassuncao, C.; Tokranov, A.K.; Wagner, C.C.; Allen, J.G. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Huang, F.; Deng, H.; Schaffrath, C.; Spencer, J.B.; O’hagan, D.; Naismith, J.H. Crystal structure and mechanism of a bacterial fluorinating enzyme. Nature 2004, 427, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurwadkar, S.; Dane, J.; Kanel, S.R.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Cawdrey, R.W.; Ambade, B.; Struckhoff, G.C.; Wilkin, R. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in water and wastewater: A critical review of their global occurrence and distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151003. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Mezgebe, B.; Hejase, C.A.; Sahle-Demessie, E.; Nadagouda, M.N. Photodegradation and photocatalysis of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A review of recent progress. Next Mater. 2024, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar]

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z. An overview of the uses of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2345–2373. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Altaee, A.; Wu, M.; Xu, G. Photocatalytic removal of perfluoroalkyl substances from water and wastewater: Mechanism, kinetics and controlling factors. Chemosphere 2017, 189, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.P.; Kah, M.; Padhye, L.P. A review of the occurrence, transformation, and removal of poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2021, 199, 117187. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Halsall, C.; Codling, G.; Xie, Z.; Xu, B.; Zhao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Ebinghaus, R.; Jones, K.C. Accumulation of perfluoroalkyl compounds in tibetan mountain snow: Temporal patterns from 1980 to 2010. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.J.; Furdui, V.I.; Franklin, J.; Koerner, R.M.; Muir, D.C.; Mabury, S.A. Perfluorinated acids in arctic snow: New evidence for atmospheric formation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3455–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, D.; Jun, B.-M.; Heo, J.; Her, N.; Park, C.M.; Yoon, Y. Selected advanced water treatment technologies for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 231, 115929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunacheva, C.; Fujii, S.; Tanaka, S.; Seneviratne, S.; Lien, N.P.H.; Nozoe, M.; Kimura, K.; Shivakoti, B.R.; Harada, H. Worldwide surveys of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in water environment in recent years. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 66, 2764–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, M.S.; Holmström, K.E.; Reth, M.; Berger, U. Riverine discharge of perfluorinated carboxylates from the European continent. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 7260–7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, J.L.; Nadal, M. Human exposure to per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) through drinking water: A review of the recent scientific literature. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Castiglioni, S.; Valsecchi, S.; Polesello, S.; Rusconi, M.; Melis, M.; Palmiotto, M.; Manenti, A.; Davoli, E.; Zuccato, E. Sources and fate of perfluorinated compounds in the aqueous environment and in drinking water of a highly urbanized and industrialized area in Italy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 282, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia, G. Acque Senza Veleni. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-italy-stateless/2025/01/4bbb41f2-report_def_a_s_v_2025-1.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Italy, G. Investigation of Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS), Especially Tetrafluroacetate (TFA) in Italian Bottled Mineral Water. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-italy-stateless/2025/10/1517fe65-20250805_gpit_bottledwater_en_final_a_2.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Paul Guin, J.; Sullivan, J.A.; Thampi, K.R. Challenges facing sustainable visible light induced degradation of poly-and perfluoroalkyls (PFA) in water: A critical review. ACS Eng. Au 2022, 2, 134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.-S.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. A review on the advancement in photocatalytic degradation of poly/perfluoroalkyl substances in water: Insights into the mechanisms and structure-function relationship. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174137. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, L. Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the aquatic environment: A review of their occurrence and fate. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonello, D.; Fendrich, M.A.; Parrino, F.; Patel, N.; Orlandi, M.; Miotello, A. Light-induced advanced oxidation processes as pfas remediation methods: A review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegoda, J.N.; Bezerra de Souza, B.; Casarini, M.M.; Kewalramani, J.A. A review of PFAS destruction technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matesun, J.; Petrik, L.; Musvoto, E.; Ayinde, W.; Ikumi, D. Limitations of wastewater treatment plants in removing trace anthropogenic biomarkers and future directions: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, R.; Merdan, G.F.; Töre, G.Y. Activated sludge process for refractory pollutants removal. In Removal of Refractory Pollutants from Wastewater Treatment Plants; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 137–184. [Google Scholar]

- Łukasiewicz, E. Coagulation–Sedimentation in Water and Wastewater Treatment: Removal of Pesticides, Pharmaceuticals, PFAS, Microplastics, and Natural Organic Matter. Water 2025, 17, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbeh, G.O.; Ogunlela, A.O.; Akinbile, C.O.; Iwar, R.T. Adsorption of organic micropollutants in water: A review of advances in modelling, mechanisms, adsorbents, and their characteristics. Environ. Eng. Res. 2025, 30, 230733. [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida, R.; Porto, R.F.; Quintaes, B.R.; Bila, D.M.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Campos, J.C. A review on membrane concentrate management from landfill leachate treatment plants: The relevance of resource recovery to close the leachate treatment loop. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yuan, T.; Yang, X.; Ding, S.; Ma, M. Insights into photo/electrocatalysts for the degradation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) by advanced oxidation processes. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1308. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, I.M.; Pinto da Silva, L.; Esteves da Silva, J.C. Nanomaterial-based advanced oxidation/reduction processes for the degradation of PFAS. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1668. [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh Banu, J.; Merrylin, J.; Kavitha, S.; Yukesh Kannah, R.; Selvakumar, P.; Gopikumar, S.; Sivashanmugam, P.; Do, K.-U.; Kumar, G. Trends in biological nutrient removal for the treatment of low strength organic wastewaters. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2021, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, C.C.; Quen, H.L. Advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: Optimization of UV/H2O2 process through a statistical technique. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 5305–5311. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J.; Mutis, A.; Yeber, M.; Freer, J.; Baeza, J.; Mansilla, H. Chemical degradation of EDTA and DTPA in a totally chlorine free (TCF) effluent. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

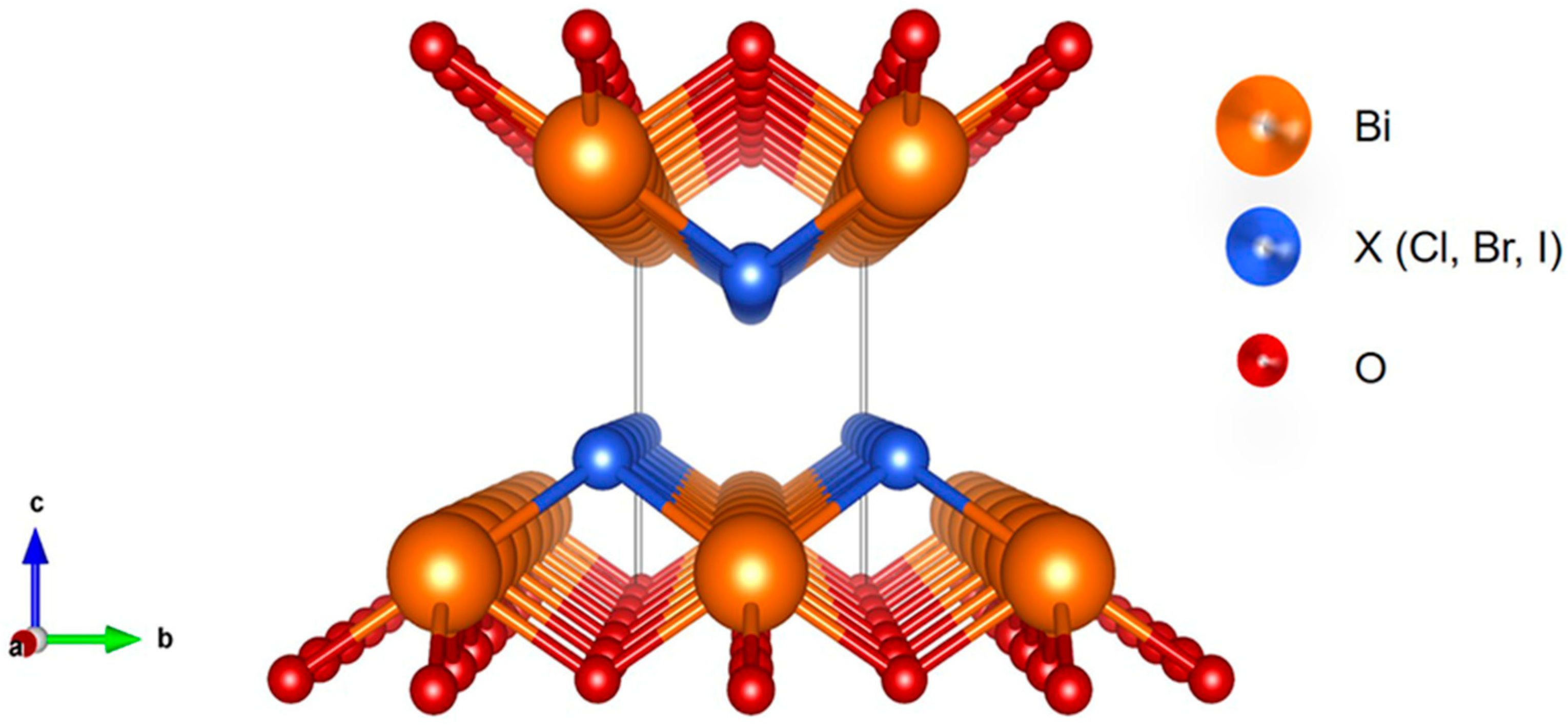

- Wang, B.; Yang, C.; Zhong, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Miao, J. Photocatalytic properties of visible light-responsive rGO/BiOCl photocatalysts benefited from enriched oxygen vacancies. Solid State Sci. 2023, 138, 107155. [Google Scholar]

- Gulumian, M.; Andraos, C.; Afantitis, A.; Puzyn, T.; Coville, N.J. Importance of surface topography in both biological activity and catalysis of nanomaterials: Can catalysis by design guide safe by design? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, R.; El-Sayed, M.A. Shape-dependent catalytic activity of platinum nanoparticles in colloidal solution. Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Ji, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xie, H.; Zhang, L. Unique S-scheme structures in electrostatic self-assembled ReS2-TiO2 for high-efficiency perfluorooctanoic acid removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 681, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

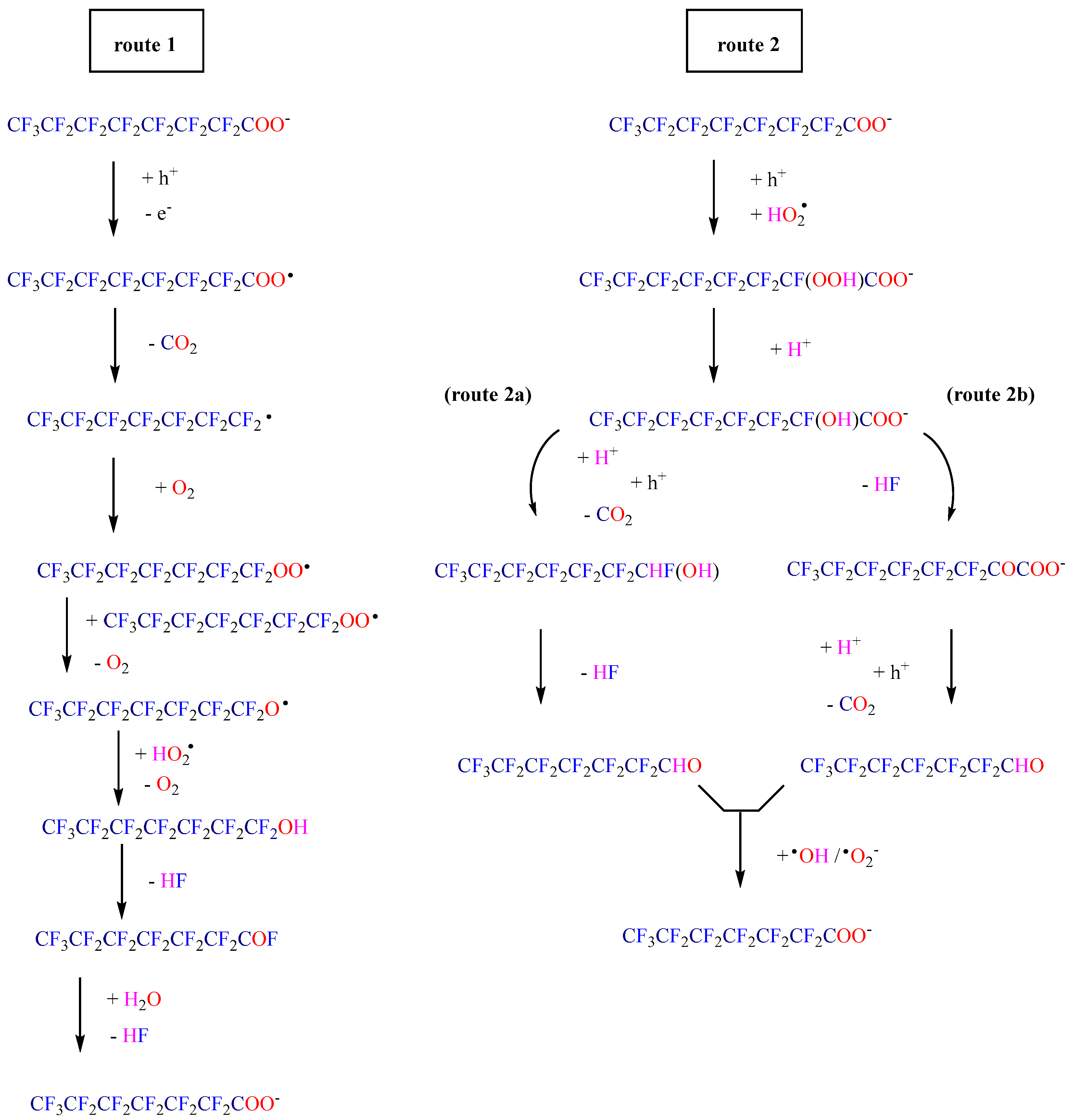

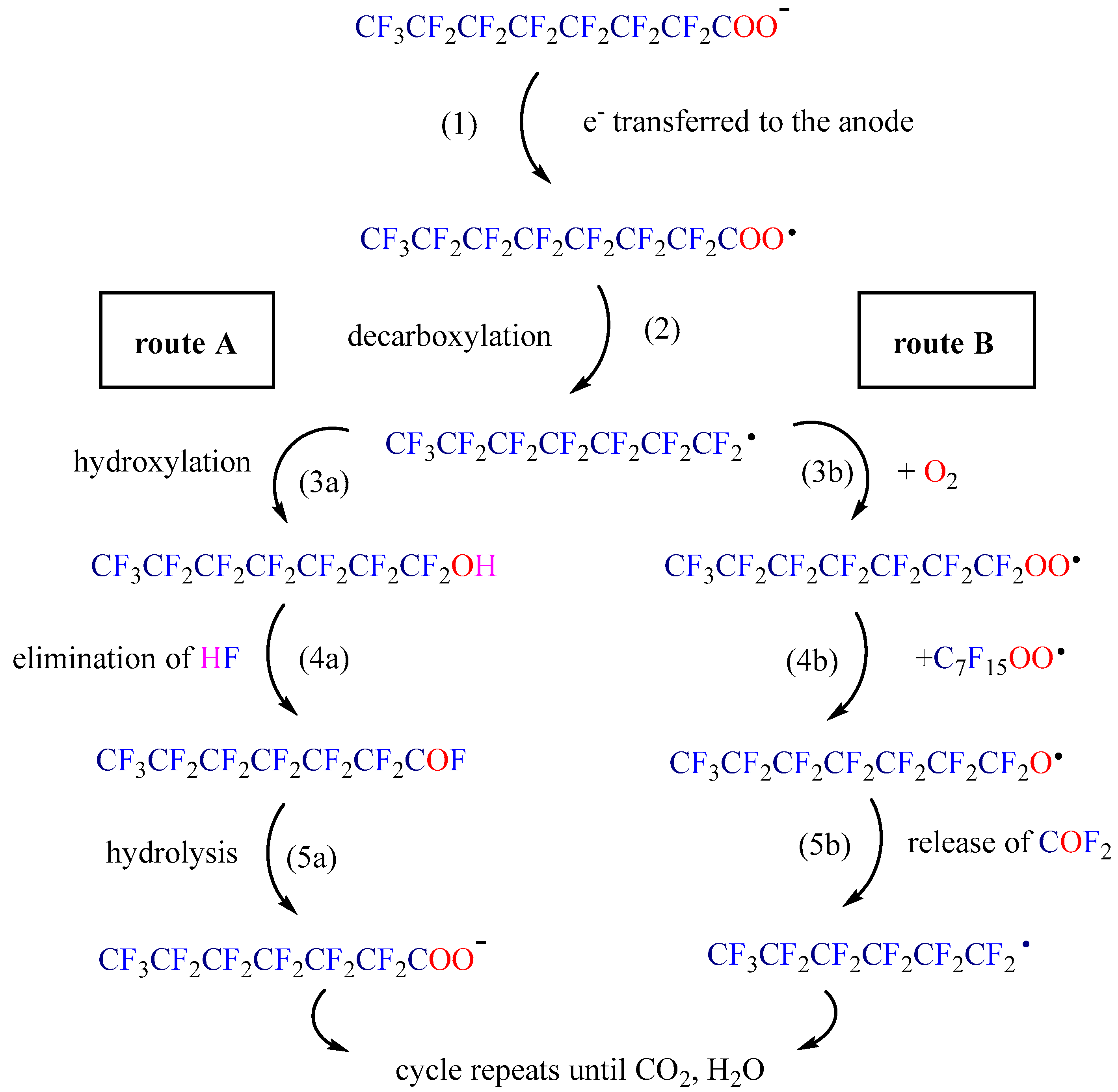

- Do, H.T.; Phan Thi, L.A.; Dao Nguyen, N.H.; Huang, C.W.; Le, Q.V.; Nguyen, V.H. Tailoring photocatalysts and elucidating mechanisms of photocatalytic degradation of perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) in water: A comparative overview. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2569–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojamberdiev, M.; Larralde, A.L.; Vargas, R.; Madriz, L.; Yubuta, K.; Sannegowda, L.K.; Sadok, I.; Krzyszczak-Turczyn, A.; Oleszczuk, P.; Czech, B. Unlocking the effect of Zn2+ on crystal structure, optical properties, and photocatalytic degradation of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) of Bi2WO6. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2023, 9, 2866–2879. [Google Scholar]

- Qanbarzadeh, M.; Wang, D.; Ateia, M.; Sahu, S.P.; Cates, E.L. Impacts of reactor configuration, degradation mechanisms, and water matrices on perfluorocarboxylic acid treatment efficiency by the UV/Bi3O (OH)(PO4) 2 photocatalytic process. ACS EST Eng. 2020, 1, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, I.; Fu, Z.; Li, K.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, L. A comparative study of bismuth-based photocatalysts with titanium dioxide for perfluorooctanoic acid degradation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 2225–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Ji, H.; Gu, Y.; Tong, T.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, D. Enhanced adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid in water using iron (hydr) oxides/carbon sphere composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124230. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L. Highly efficient photocatalytic degradation toward perfluorooctanoic acid by bromine doped BiOI with high exposure of (001) facet. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 268, 118442. [Google Scholar]

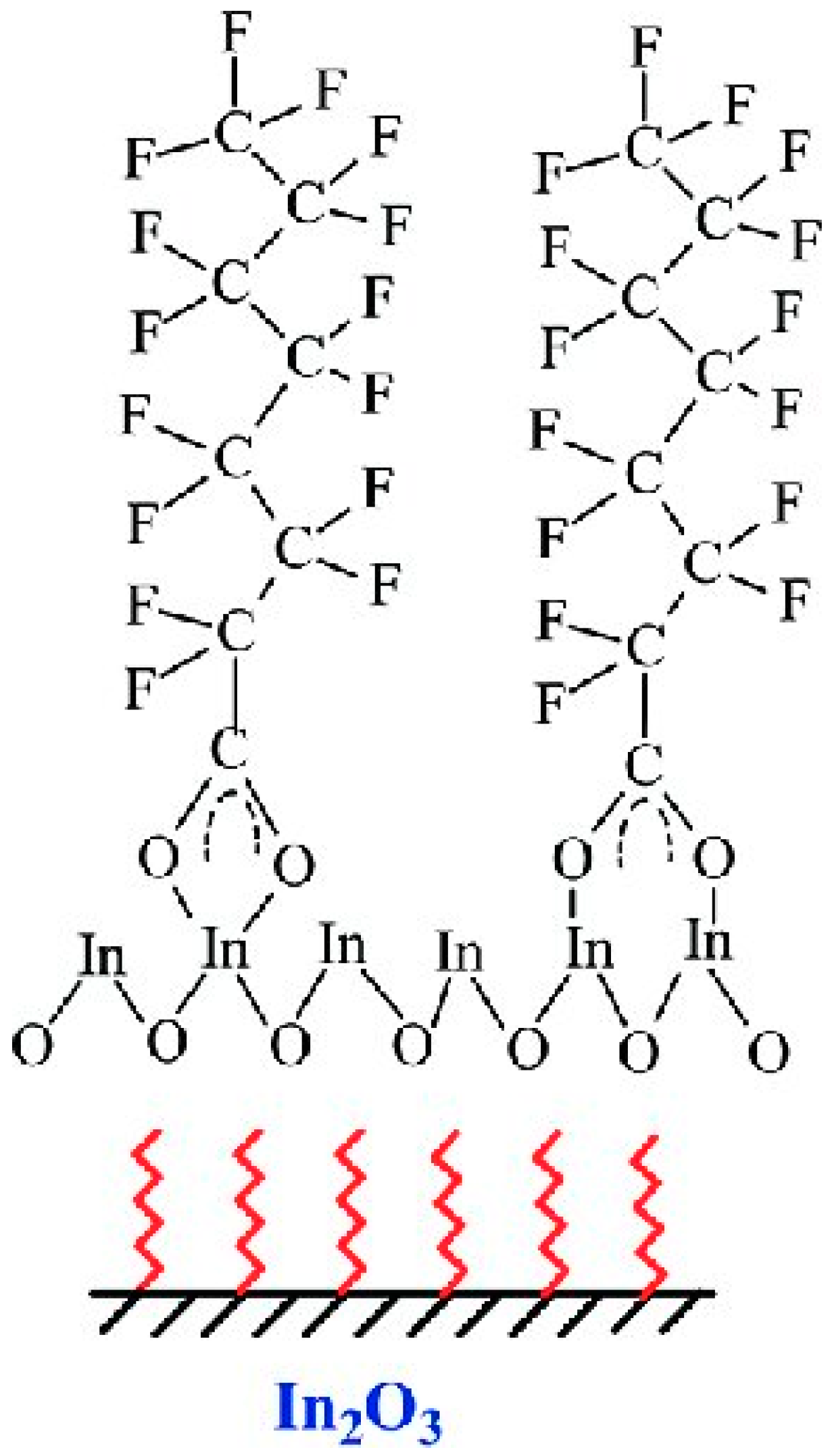

- Li, Z.; Zhang, P.; Shao, T.; Wang, J.; Jin, L.; Li, X. Different nanostructured In2O3 for photocatalytic decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Chen, G.; Xing, D.; Ding, W.; Liu, H.; Li, T.; Huang, Y. Indium-modified Ga2O3 hierarchical nanosheets as efficient photocatalysts for the degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Lim, X.; Yang, H.; Goodson, B.M.; Liu, J. Degradation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in wastewater effluents by photocatalysis for water reuse. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 46, 102556. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sun, L.; Yu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Peng, Z.; Yang, F.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J. Synergetic decomposition performance and mechanism of perfluorooctanoic acid in dielectric barrier discharge plasma system with Fe3O4@ SiO2-BiOBr magnetic photocatalyst. Mol. Catal. 2017, 441, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cao, C.-S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. Insights into highly efficient photodegradation of poly/perfluoroalkyl substances by In-MOF/BiOF heterojunctions: Built-in electric field and strong surface adsorption. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 304, 121013. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Qiu, P.; Chen, H.; Jiang, F. Platinum modified indium oxide nanorods with enhanced photocatalytic activity on degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 80, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Fang, C.; Li, C. Highly efficient degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid over a MnOx-modified oxygen-vacancy-rich In2O3 photocatalyst. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2297–2303. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-J.; Lo, S.-L.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kuo, J.; Wu, C.-H. Decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid by ultraviolet light irradiation with Pb-modified titanium dioxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 303, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, C.B.; Mohammad, A.W.; Ng, L.Y.; Mahmoudi, E.; Azizkhani, S.; Hairom, N.H.H. Solar photocatalytic and surface enhancement of ZnO/rGO nanocomposite: Degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid and dye. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 112, 298–307. [Google Scholar]

- Guin, J.P.; Sullivan, J.A.; Muldoon, J.; Thampi, K.R. Visible light induced degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid using iodine deficient bismuth oxyiodide photocatalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, T.; Zhang, P.; Li, Z.; Jin, L. Photocatalytic decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid in pure water and wastewater by needle-like nanostructured gallium oxide. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Si, C.; Zhong, L.; Duan, X.; Zhang, D.; Xu, W. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid using BiOCl@ PMoV-X heterojunction photocatalyst coupled with persulfate activation. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106791. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Cao, W.; Liu, Z.; Kong, D.; Jiang, W. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid by bismuth nanoparticle modified titanium dioxide. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172028. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Xu, L.; He, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ghumro, J.A.; Dong, K. MXene and its composites combined with photocatalytic degradation of Perfluorooctanoic acid: Efficiency and active species study. Environ. Res. 2025, 278, 121690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnor, B.; Eshun, A.; Prabakaran, E.; Adeiga, O.I.; Curtis, C.; Pillay, K. The investigations of photocatalytic degradation and defluorination of perfluorooctanoic acid using palm kernel shell activated carbon and Fe-Sn binary oxides nanocomposite under visible light irradiation. Results Chem. 2025, 17, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Gu, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, L.; Cheng, X.; Huang, J. Mechanism of Z-scheme BN/BiOI heterojunction for efficient photodegradation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 131229. [Google Scholar]

- Mazen, K.; Venkatesh, G.; Samara, F.; Kanan, S. ZnO/BiOI heterojunction catalyst: Efficient photocatalytic decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and mixed dye pollutants in wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Pervez, M.N.; Ilango, A.K.; Liang, Y. Enhanced removal and destruction of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) mixtures by coupling magnetic modified clay and photoreductive degradation. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106733. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, C.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, J.; Feng, K.; Xing, D. Enhanced photocatalytic defluorination of perfluorooctanoic acid through integrated hydrogen atoms/electrons reduction and ROS oxidation with metal–organic framework heterogeneous catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 163058. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Li, H.; Yu, H. Study on the performance and mechanism of ap–n type In2O3/BiOCl heterojunction prepared using a sacrificial MOF framework for the degradation of PFOA. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15029–15051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Jin, L.; Shao, T.; Li, Z.; Cao, J. Efficient photocatalytic decomposition of perfluorooctanoic acid by indium oxide and its mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5528–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Cabrera, G.X.; Espinoza-Montero, P.J.; Alulema-Pullupaxi, P.; Mora, J.R.; Villacís-García, M.H. Bismuth oxyhalide-based materials (BiOX: X = Cl, Br, I) and their application in photoelectrocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in water: A review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 900622. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Huitle, C.A.; Ferro, S. Electrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants for the wastewater treatment: Direct and indirect processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Mollah, M.Y.A.; Susan, M.A.B.H.; Islam, M.M. Role of in situ electrogenerated reactive oxygen species towards degradation of organic dye in aqueous solution. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 344, 136146. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, F.C.; Boaventura, R.A.; Brillas, E.; Vilar, V.J. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: A review on their application to synthetic and real wastewaters. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 202, 217–261. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin, B.P. Critical review of electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for water treatment applications. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2014, 16, 1182–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. A review: Synthesis and applications of titanium sub-oxides. Materials 2023, 16, 6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Jain, A.; Meese, A.; Yan, Y.; Xu, X.; Kim, J.; Muhich, C. Photo-Electrochemical Reduction of PFAS in Complex Water Matrices. Res. Sq. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzcinski, A.P.; Harada, K.H. Comparison of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS) removal in a combined adsorption and electrochemical oxidation process. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeidabadi, F.A.; Esfahani, E.B.; Moreira, R.; McBeath, S.T.; Foster, J.; Mohseni, M. Structural dependence of PFAS oxidation in a boron doped diamond-electrochemical system. Environ. Res. 2024, 246, 118103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, Q.; Wang, J.; Niu, J.; Yang, B.; Yang, Y. Electrochemical oxidation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) substitute by modified boron doped diamond (BDD) anodes. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 379, 122280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, J.; Jiang, C.; Li, J.; Yu, G.; Deng, S.; Lu, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, C.; Zhuo, Q. Electrochemical mineralization of perfluorooctane sulfonate by novel F and Sb co-doped Ti/SnO2 electrode containing Sn-Sb interlayer. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 316, 296–304. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Jiang, C.; Yu, G.; Zhuo, Q.; Deng, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H. Highly efficient electrochemical degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) by F-doped Ti/SnO2 electrode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Pierce, R.; Gao, S.; Huang, Q. Degradation of perfluorooctanesulfonate by reactive electrochemical membrane composed of magneli phase titanium suboxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 14528–14537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Niu, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Jin, F.; Luo, Q.; Huang, Q. Development of macroporous Magnéli phase Ti4O7 ceramic materials: As an efficient anode for mineralization of poly-and perfluoroalkyl substances. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 354, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wang, K.; Niu, J.; Chu, C.; Weon, S.; Zhu, Q.; Lu, J.; Stavitski, E.; Kim, J.-H. Amorphous Pd-loaded Ti4O7 electrode for direct anodic destruction of perfluorooctanoic acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 10954–10963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barisci, S.; Suri, R. Electrooxidation of short and long chain perfluorocarboxylic acids using boron doped diamond electrodes. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Niu, J.; Ding, S.; Zhang, L. Electrochemical degradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) by Ti/SnO2–Sb, Ti/SnO2–Sb/PbO2 and Ti/SnO2–Sb/MnO2 anodes. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.X.H.; Haflich, H.; Shah, A.D.; Chaplin, B.P. Energy-efficient electrochemical oxidation of perfluoroalkyl substances using a Ti4O7 reactive electrochemical membrane anode. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, C.; Xu, Y.; Wan, A.; Wang, M.; Han, Q. Electrochemical destruction of PFAS at low oxidation potential enabled by CeO2 electrodes utilizing adsorption and activation strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 137043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomri, C.; Makhoul, E.; Koundia, F.N.; Petit, E.; Raffy, S.; Bechelany, M.; Semsarilar, M.; Cretin, M. Electrochemical advanced oxidation combined to electro-Fenton for effective treatment of perfluoroalkyl substances “PFAS” in water using a Magnéli phase-based anode. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Pu, R.; Deng, S.; Lin, L.; Mantzavinos, D.; Naidu, R.; Fang, C.; Lei, Y. Enhanced electrochemical degradation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) by activating persulfate on boron-doped diamond (BDD) anode. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchimaru, T.; Tsuzuki, S.; Sugie, M.; Tokuhashi, K.; Sekiya, A. Ab initio study of the hydrolysis of carbonyl difluoride (CF2O): Importance of an additional water molecule. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 396, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Peng, M.; Huang, Q.; Huang, C.-H.; Chen, Y.; Hawkins, G.; Li, K. A review on the recent mechanisms investigation of PFAS electrochemical oxidation degradation: Mechanisms, DFT calculation, and pathways. Front. Environ. Eng. 2025, 4, 1568542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, J.R.; Bircher, K.G.; Tumas, W.; Tolman, C.A. Figures-of-merit for the technical development and application of advanced oxidation technologies for both electric-and solar-driven systems (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2001, 73, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.J.; Lauria, M.; Ahrens, L.; McCleaf, P.; Hollman, P.; Bjälkefur Seroka, S.; Hamers, T.; Arp, H.P.H.; Wiberg, K. Electrochemical oxidation for treatment of PFAS in contaminated water and fractionated foam—A pilot-scale study. ACS Est Water 2023, 3, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Fenti, A.; Jin, Y.; Rhoades, A.J.H.; Dooley, G.P.; Iovino, P.; Salvestrini, S.; Musmarra, D.; Mahendra, S.; Peaslee, G.F.; Blotevogel, J. Performance testing of mesh anodes for in situ electrochemical oxidation of PFAS. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 9, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Niu, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, H.; Li, D.; Yue, Z.; Feng, C. Highly efficient and mild electrochemical mineralization of long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (C9–C10) by Ti/SnO2–Sb–Ce, Ti/SnO2–Sb/Ce–PbO2, and Ti/BDD electrodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 13039–13046. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, B.; Li, Y.; Xue, X.-S.; Ateia, M.; Houk, K.; Dichtel, W.R. Low-temperature mineralization of perfluorocarboxylic acids. Science 2022, 377, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Z.; Goult, C.A.; Schlatzer, T.; Paton, R.S.; Gouverneur, V. Phosphate-enabled mechanochemical PFAS destruction for fluoride reuse. Nature 2025, 640, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Photocatalyst | Light | PFAS C0 | Catalyst Dosage | pH | Time | Deg. eff. | Defl. eff. | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn2+-Bi2WO6 | Visible 150 W | PFHxA 5 mg/L | 0.4 g/L | - | 45 min | 57% | - | [37] |

| Bi3O(OH)(PO4)2 | UV | PFOA 54 mg/L | 1.8 g/L | ~4.0 | 1 h | >99% | - | [38] |

| BiOCl | UV | PFOA 20 mg/L | 1 g/L | sp. | 0.5 h | 99.99% | - | [39] |

| FeO/CS (1:1) | Solar | PFOA (pre-adsorbed) 0.2 mg/L | 1 g/L | 7.0 | 4 h | 95.2% | 57.2% | [40] |

| BiOI0.95Br0.05 | UV 300 W | PFOA 20 mg/L | 0.4 g/L | - | 2 h | 100% | 65% in 3 h | [41] |

| In2O3 microspheres | UV 15 W | PFOA 30 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | ~3.9 | 20 min | 100% | [42] | |

| Fe/TNTs@AC | Solar | PFOA 0.2 mg/L | 1 g/L | ~7.0 | 4 h | 90.1% | 62% in 4 h | [43] |

| Bare Fe0 NPs | UVC 4.24 mW/cm2 | PFOA 0.5 mg/L PFOS 0.5 mg/L PFNA 0.5 mg/L (mix in real wastewater) | 0.1 g/L | 3.0 | 2 h | 46% 88% 90% | - | [44] |

| Fe3O4@SiO2-BiOBr | UV and Visible (DBD) | PFOA 20 mg/L | 0.1 g/L | 4.28 | 1 h | 92.9% | 32.8% | [45] |

| 20% In-MOF/BiOF | UV 500 W | PFOA 15 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | - | 2.5 h | 100% | 34% (in 3 h) | [46] |

| 3% Pt/In2O3 nanorods | UV500 W | PFOA 200 mg/L | 0.4 g/L | - | 1 h | 98% | - | [47] |

| In-Ga2O3 hierarchical nanosheets | UV 200 W | PFOA 20 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | 4.5 | 1 h | 100% | 57% (in 4 h) | [43] |

| (4%) MnOx/In2O3-Ov-rich sub-micro rods | Solar 500 WUV500 W | PFOA 50 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | - | 3 h 10 min | 99.8% 98% | 17.4% 95.7% in 4 h | [48] |

| (2%) Pb-TiO2 | UV 400 W | PFOA 50 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | 53 | 2 h 15 min | 100% 100% | 40.7% - | [49] |

| ZnO/rGO | Solar | PFOA 100 mg/L | 1 g/L | 7 | 1 h | 90.9% | - | [50] |

| Bi4O5I2 + Bi5O7I | Solar 700 W | PFOA 1 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | ~6.8 | 2 h | 94% | 65% | [51] |

| Needle-like β-Ga2O3 | UV 14 W | PFOA 0.5 mg/L | 0.5 g/L | ~4.8 | 1 h | 100% | - | [52] |

| 2% rGO/BiOCl | UV 125 W | PFOA PFOS 10 mg/L | 1 g/L | - | 1 h | 90.1% 66.2% | - | [32] |

| BiOCl@PMoV (0.9 g/L persulfate) | UV 300 W | PFOA 100 mg/L | 1.5 g/L | 3 | 6 h | 95.0% | 44.4% | [53] |

| Bi/TiO2 | UV 400 W | PFOA 50 mg/L | 0.1 g/L | 3 | 0.5 h | 99.3% | 55.3% (in 2 h) | [54] |

| MXene/TiO2 | UV | PFOA 20 mg/L | 0.13 g/L | 5.2 | 9 h | 94.6% | 58.4% | [55] |

| Palm kernel shell activated carbon- Fe2O3/SnO2 | Visible 250 W | PFOA 20 mg/L | 10 mg/L | 5 | 6 h | 92.4% | 51.2% | [56] |

| 2% ReS2-TiO2 | UV | PFOA 2 mg/L | - | 3 | 2 h | 98% | 75% | [35] |

| BN/BiOI-2:1 | UV | PFOA PFOS C7 Gen-X F-53B 6:2 FTS F-53 | 1.5 g/L | 3 | 2 h 2 h 6 h 6 h 6 h 6 h 6 h | 100% 100% 77% 7.3% 100% 100% 67.6% | 45.4% in 6 h (PFOS) | [57] |

| BiOI/ZnO 4:1 ZnO/BiOI 4:1 | Solar 500 W | PFOA 10 mg/L | - | - | 1 h 3 h | 100% 100% | 100% (in 5 h) 100% (in 5 h) | [58] |

| Magnetic modified clay + Na2SO3 + KI (Photoreductive system) | UV | PFOA 1 mg/L | 2.5 g/L MMC, 50 mM Na2SO3, 10 mM KI | 12 | 48 h | 100% | 66.5 ± 1.1% | [59] |

| Fe-BTC/BiOCl BTC: iron-based metal–organic framework (MOF) | Visible 5 W | PFOA 10 mg/L | 0.2 g/L | - | 0.5 h | 98.7% | 31.1% | [60] |

| 30% In2O3/ BiOCl | UV 500 W | PFOA 20 mg/L | 0.2 g/L | 5 | 2 h | - | 84% | [61] |

| Anode | Cathode | Cell type | PFAS | C0 | Time | Deg eff. | Mineralization | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphite Intercalated Compound (Ads.+ EO) | Stainless Steel | Divided cells | PFOS PFOA PFBS | 100 μg/L 45 μg/L 10 μg/L | 5 cycles 3 cycles 5 cycles (1 cycle: 20 min ads + 10 min reaction) | 100% 98% 17% | By-products below 100 ng/L (PFOS) | [70] |

| BDD | Stainless Steel | Single cell | PFOA PFBA GenX 6:2FTCA | 20 mg/L | 2 h | 97.9% 65.6% 84.9% 99.4% | 68.6% (Defl.) 60.8% (Defl.) 71.2% (Defl.) 63.1% (Defl.) | [71] |

| BDD/SnO2-F | Pt sheet | Single cell | F-53B | 100 mg/L | 0.5 h | 95.6% | 61.4% (Defl.) | [72] |

| Ti/Sn-Sb/SnO2-F-Sb multilayer | Ti plate | Single cell | PFOS | 100 mg/L | 2 h | >99% | 87.1% (TOC) | [73] |

| Ti/SnO2-F | Ti plate | Single cell | PFOA | 100 mg/L | 0.5 h | 99.6% | 98.3% (TOC) | [74] |

| Porous Ti4O7 (REM) | Stainless Steel | Single cell | PFOS | 2.0 μM | 100 min | 99.1% | - | [75] |

| Porous Ti4O7 | Stainless Steel | Single cell | PFOA PFOS | 0.5 mM 0.1 mM | 3 h | >99.9% 93.1% | >95% (TOC) 90.3% (TOC) | [76] |

| Ti4O7 doped with amorphous Pd | Ti plate | Single cell | PFOA | 0.12 mM | 1 h | >90% | 99.7% (TOC) | [77] |

| Si/BDD | Si/BDD | Single cell | Short-chain (C3–C6) and long-chain (C7–C18) PFCAs | 200 mg/L | 1 h | C10–C18: 95% C6: 70% C5: 66% C4: 41% C3: 39% | PFOA 37% (Defl.) Short chain PFCAs: 45% (Defl.) Long chain PFCAs: 92% (Defl.) | [78] |

| Ti/SnO2-Sb/PbO2 | Ti plate | Single cell | PFOA | 100 mg/L | 1.5 h | 91.1% | 77.4% (Defl.) | [79] |

| Ti4O7 (REM) | Stainless Steel | Single flow- through cell | PFOA PFOS | 4.14 mg/L 5 mg/L | ~11 s | PFOA/PFOS: ~5-log removal >99.9% | - | [80] |

| CeO2 | AC | Single flow- through cell | PFOA | 1 mg/L | 12 h | 94% | 73.0% (Defl.) | [81] |

| Ti4O7 | Carbon felt | Single cell | PFOA PFOS | 2 mg/L | 5 h | 92% 100% | - | [82] |

| BDD (for persulfate activation) | Ti plate | Single cell | PFOA PFOS | 50 μM | 2 h | 100% 100% | 60.4% (Defl.) 33.1% (Defl.) | [83] |

| Photocatalyst | Electrical Power [W] | Volume [L] | t90% [min] | EEO [kWh m−3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiOCl | 32 | 0.05 | 24.8 | 114.7 |

| In2O3 microspheres | 15 | 0.1 | 17.4 | 18.9 |

| Indium- modified Ga2O3 | 200 | 0.03 | 55.7 | 2688.2 |

| MnOx- modified In2O3 | 500 | 0.05 | 5.9 | 426.0 |

| (2%)Pb-TiO2 | 400 | 1.1 | 40 | 105.3 |

| needle-like Ga2O3 | 14 | 0.15 | 60.6 | 40.9 |

| Photocatalyst | Electrical Power [W] | Volume [L] | t90% [min] | EEO [kWh m−3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnOx- Modified In2O3 | 500 | 0.05 | 97.4 | 7052.2 |

| Bismuth oxyiodide | 700 | 0.01 | 81.3 | 41,176.5 |

| BiOI/ZnO 4:1 | 500 | 0.1 | 20 | 723.8 |

| Fe-BTC/BiOCl | 5 | 0.05 | 15.9 | 11.5 |

| Anode | Pollutant | Current Density or Applied Potential | Time | Deg. Eff. | Charge [F mol−1 PFAS] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphite Intercalated Compound (Ads. + EO) | PFOS PFOA PFBS | 28 mA/cm2 25 mA/cm2 43 mA/cm2 | 100% 98% 17% | - | [70] | |

| BDD | PFOA PFBA GenX 6:2 FTCA | 10 mA⋅cm−2 | 2 h | 97.9% 65.6% 84.9% 99.4% | 1042 803.5 1007 1061 | [71] |

| BDD/SnO2-F | F-53B | 30 mA/cm2 | 95.6% | 150.3 | [72] | |

| Ti/Sn-Sb/SnO2-F-Sb multilayer | PFOS | 20 mA/cm2 | >99% | 37.40 | [73] | |

| Ti/SnO2-F | PFOA | 20 mA⋅cm−2 | 0.5 h | 99.6% | 7.760 | [74] |

| Porous tubularTi4O7 (REM) | PFOS | 4 mA⋅cm−2 | 100 min | 99.1% | 31,790 | [75] |

| Porous Ti4O7 | PFOAPFOS | 5 mA⋅cm−2 | 3 h | >99.9% 93.1% | 280.2 1503 | [76] |

| Ti4O7 doped with amorphous Pd | PFOA | 10 mA/cm2 | >90% | 2861 | [77] | |

| Si/BDD | Short-chain (C3-C6) and long-chain (C7-C18) PFCAs | 25 mA⋅cm−2 | 1 h | Long-chain (C10-C18): 95% C3: 39% C4: 41% C5: 66% C6: 70% | - | [78] |

| Ti/SnO2-Sb/PbO2 | PFOA | 10 mA⋅cm−2 | 1.5 h | 91.1% | 1526 | [79] |

| Ti4O7 (REM) | PFOA PFOS | 3.3 V 3.6 V | PFOA/PFOS: ~5-log removal >99.9% | - | [80] | |

| CeO2 | PFOA | 1.4 V | 94% | - | [81] | |

| Ti4O7 | PFOA PFOS | 13 mA⋅cm−2 | 92% 100% | 81,865 90,970 | [82] | |

| BDD (for persulfate activation) | PFOA PFOS | 40 mA⋅cm−2 | 100% 100% | 7165 7166 | [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vietri, V.; Vaiano, V.; Sacco, O.; Mancuso, A. Photocatalysis and Electro-Oxidation for PFAS Degradation: Mechanisms, Performance, and Energy Efficiency. Catalysts 2026, 16, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020145

Vietri V, Vaiano V, Sacco O, Mancuso A. Photocatalysis and Electro-Oxidation for PFAS Degradation: Mechanisms, Performance, and Energy Efficiency. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020145

Chicago/Turabian StyleVietri, Vincenzo, Vincenzo Vaiano, Olga Sacco, and Antonietta Mancuso. 2026. "Photocatalysis and Electro-Oxidation for PFAS Degradation: Mechanisms, Performance, and Energy Efficiency" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020145

APA StyleVietri, V., Vaiano, V., Sacco, O., & Mancuso, A. (2026). Photocatalysis and Electro-Oxidation for PFAS Degradation: Mechanisms, Performance, and Energy Efficiency. Catalysts, 16(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020145