Production of Methane and Ethane with Photoreduction of CO2 Using Nanomaterials of TiO2 (Anatase–Brookite) Modifications with Cobalt

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.2. Rietveld Refinement

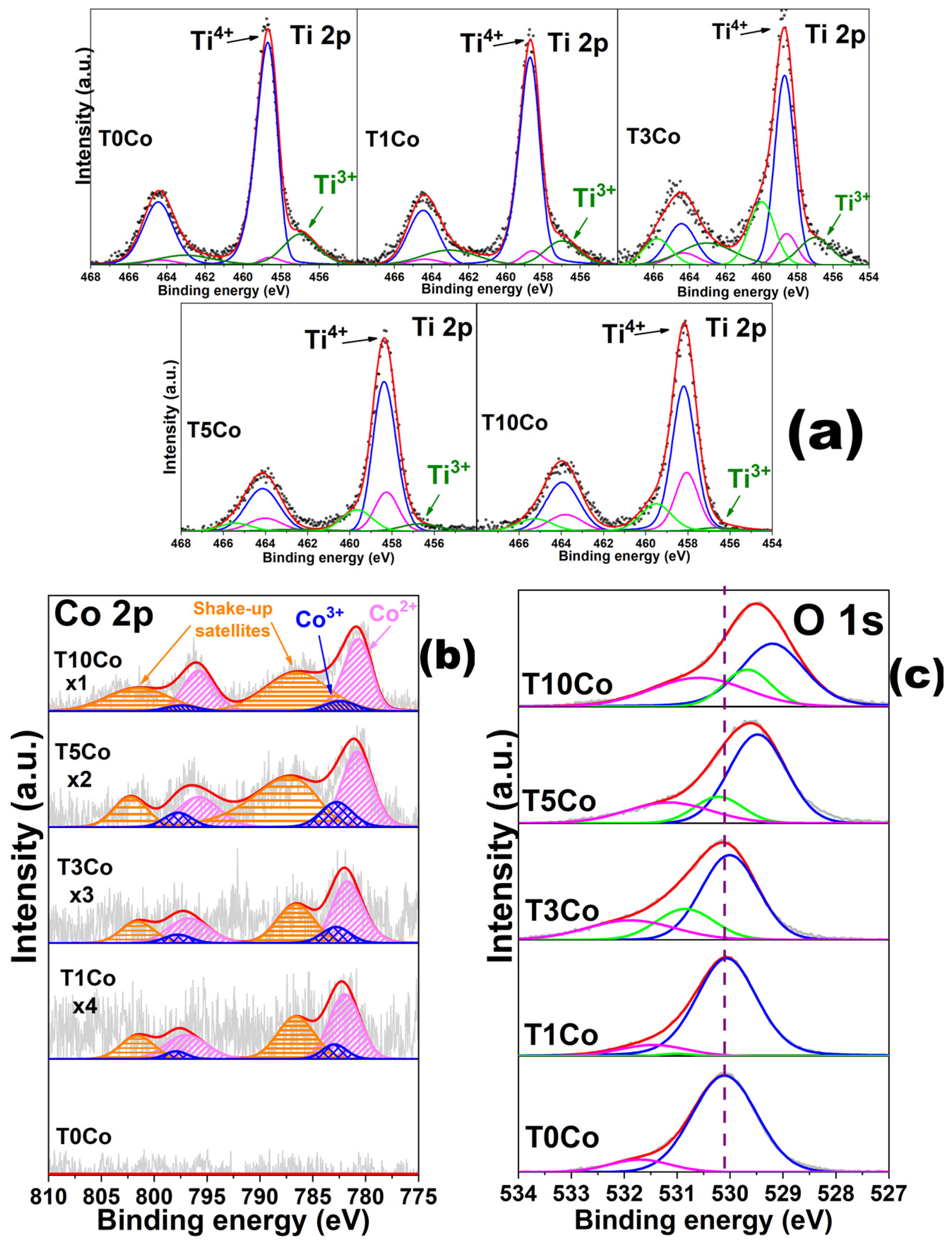

2.3. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

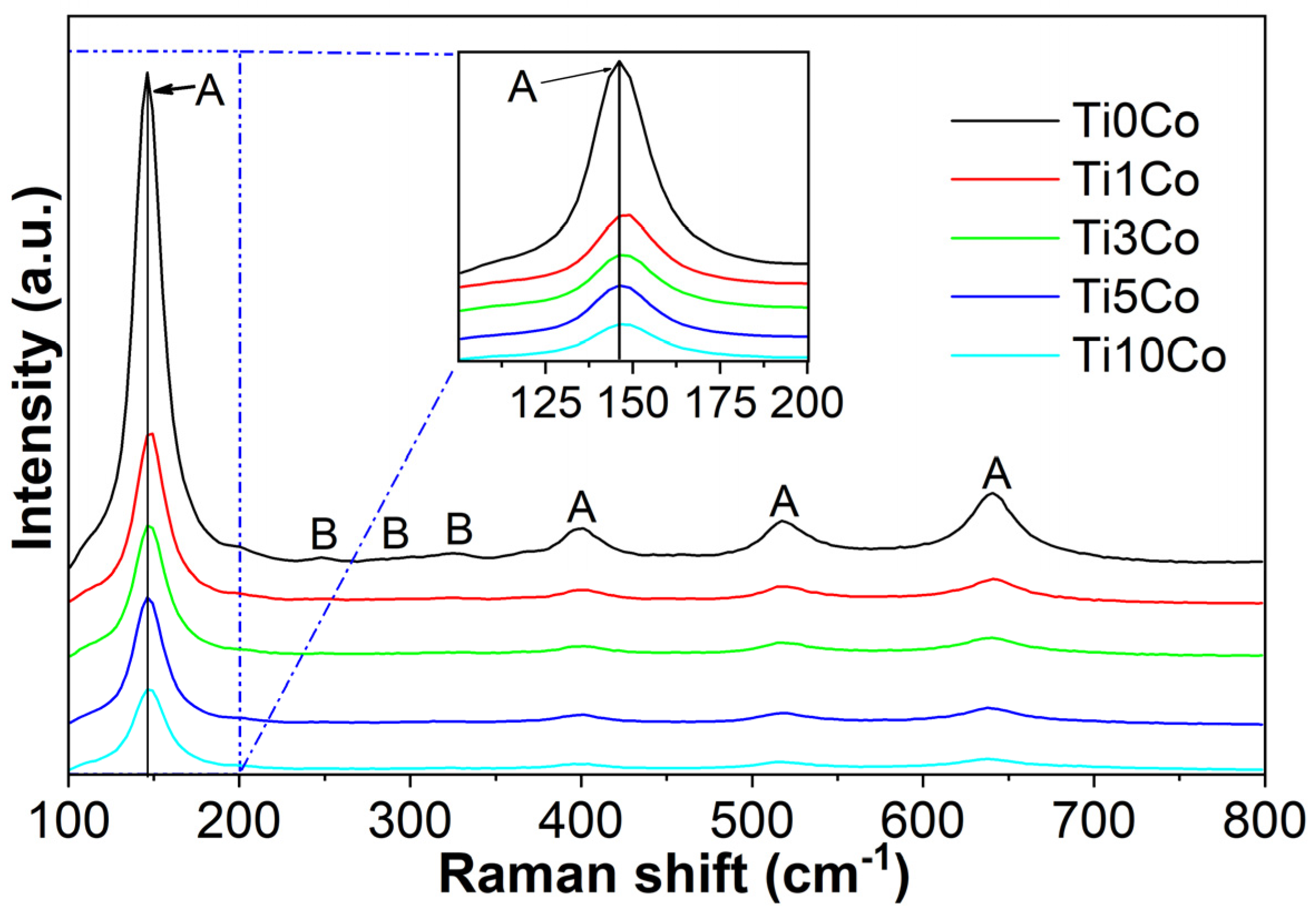

2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

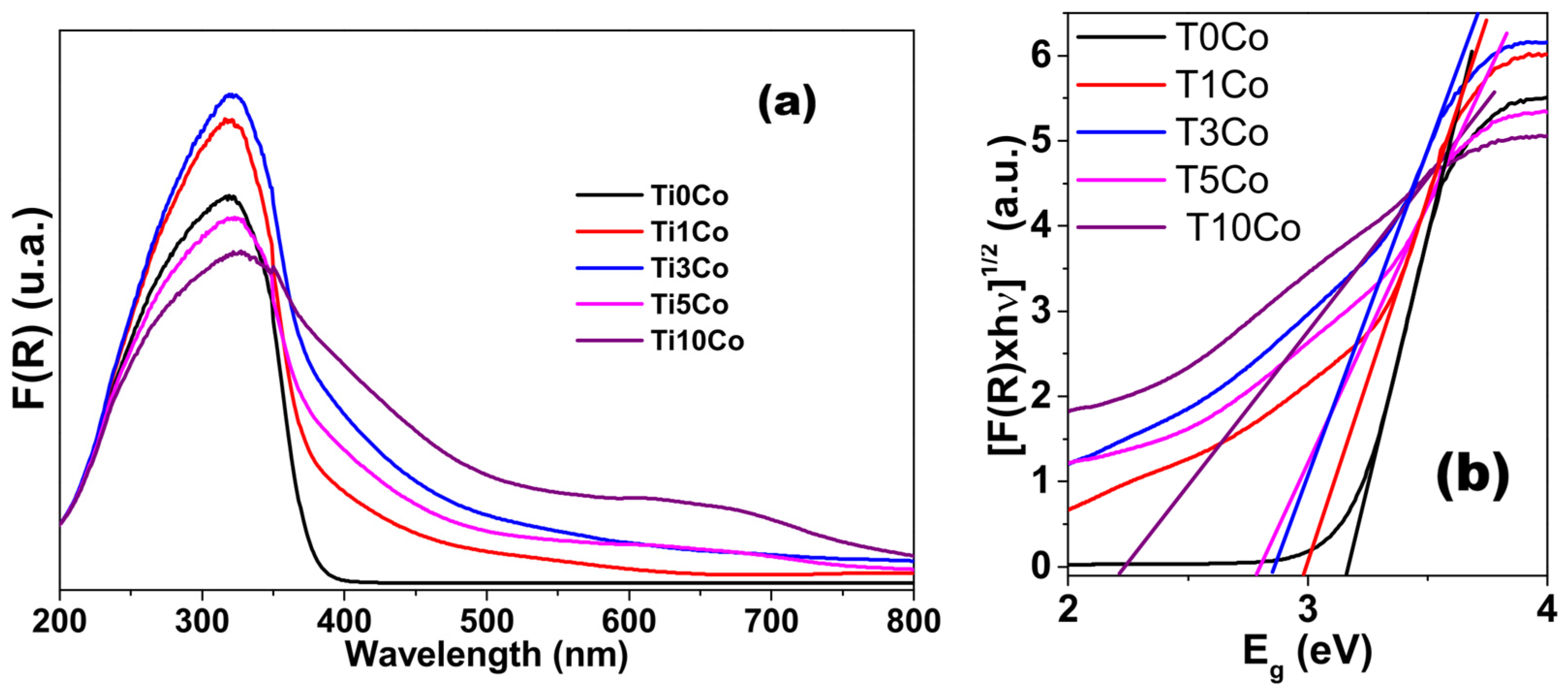

2.5. Diffuse Reflectance (DRS)

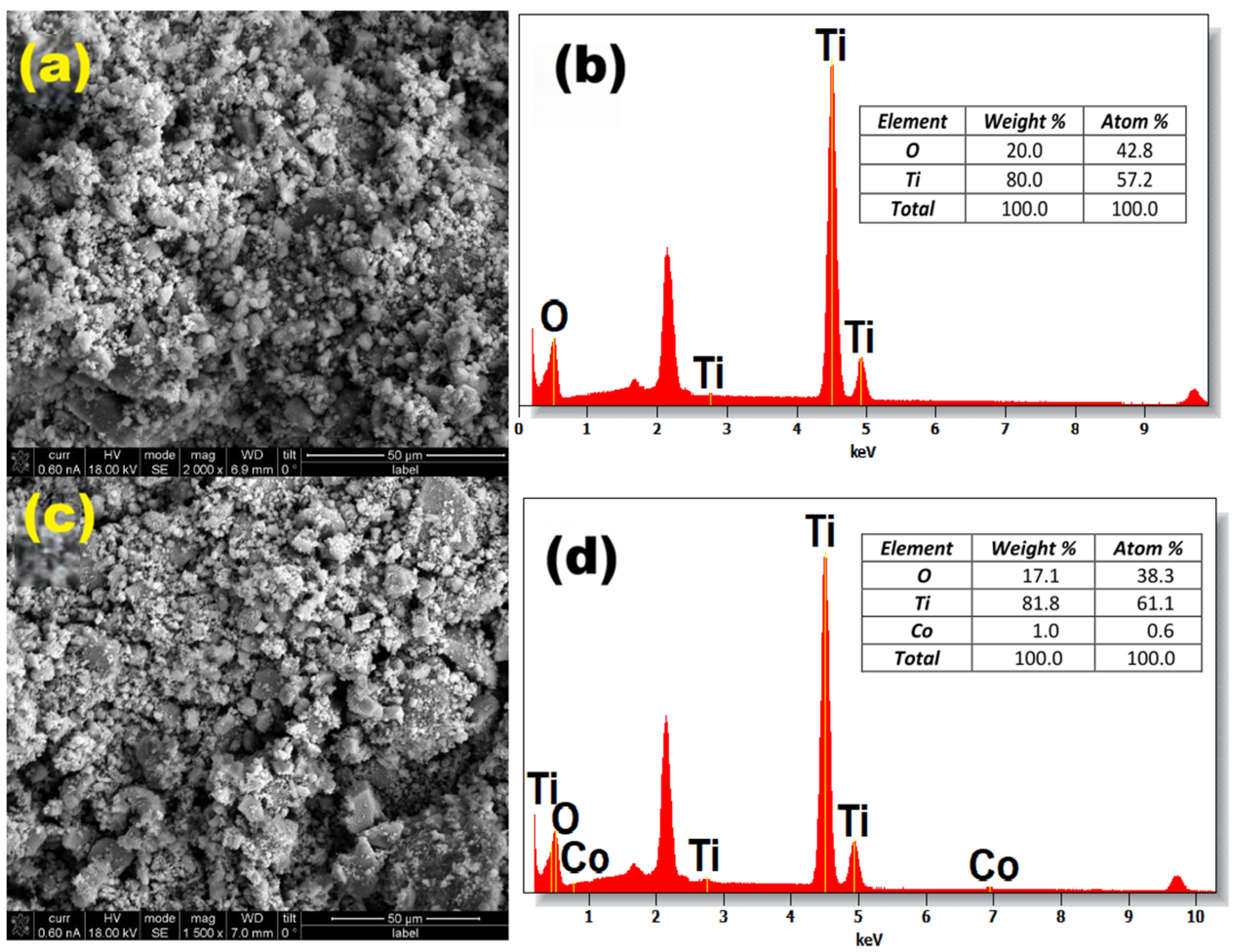

2.6. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray-Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM-EDS)

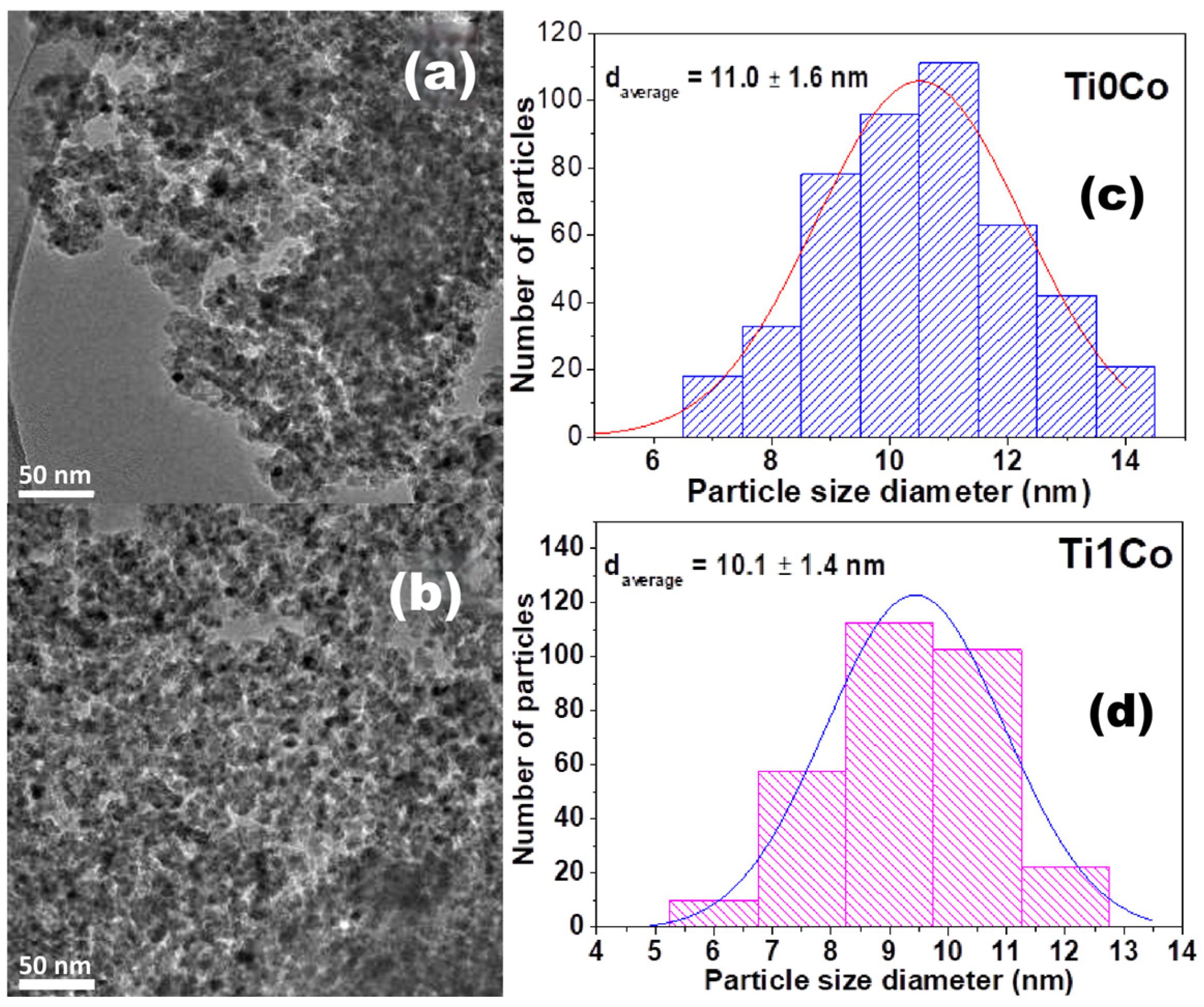

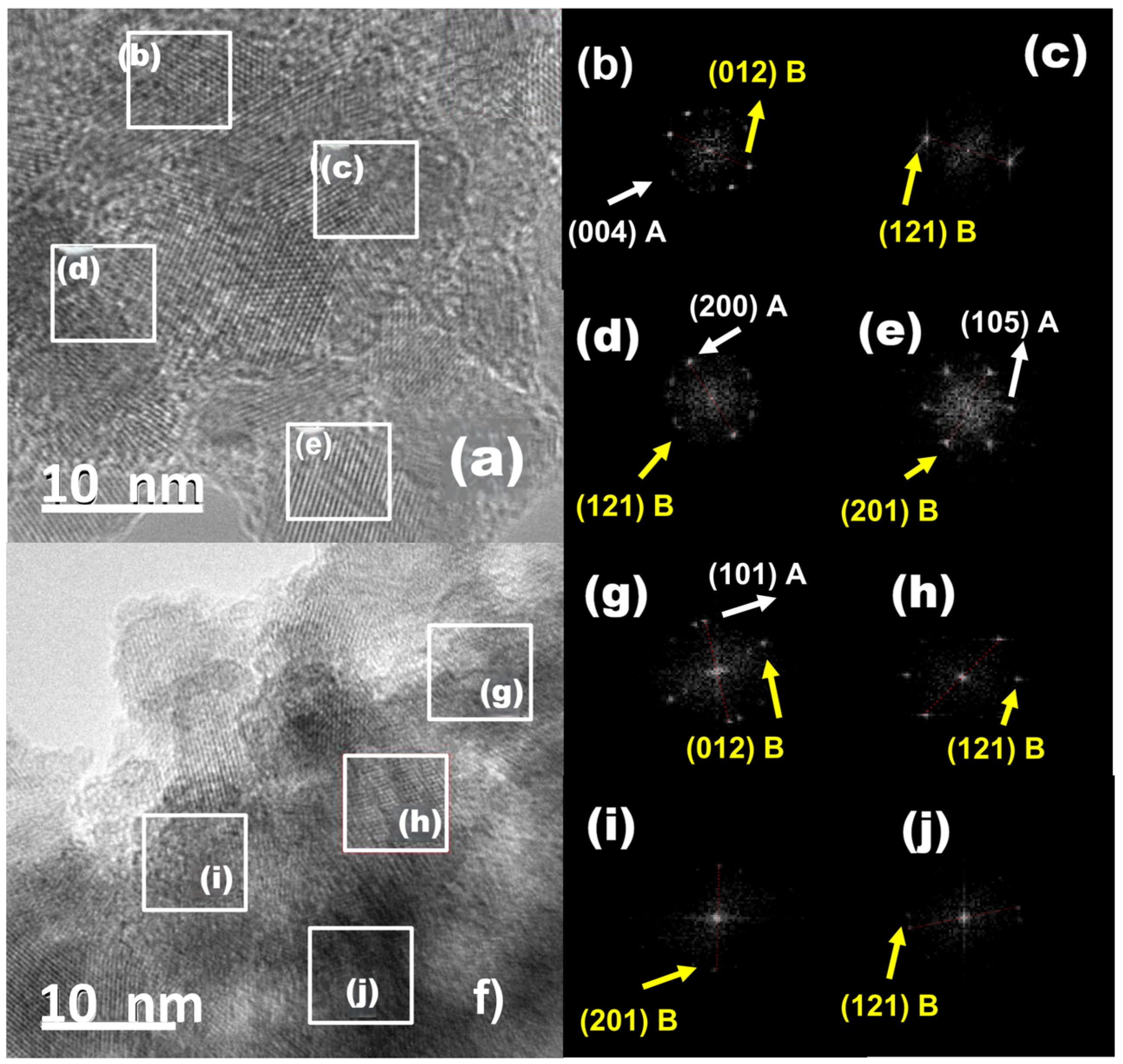

2.7. TEM-HRTEM

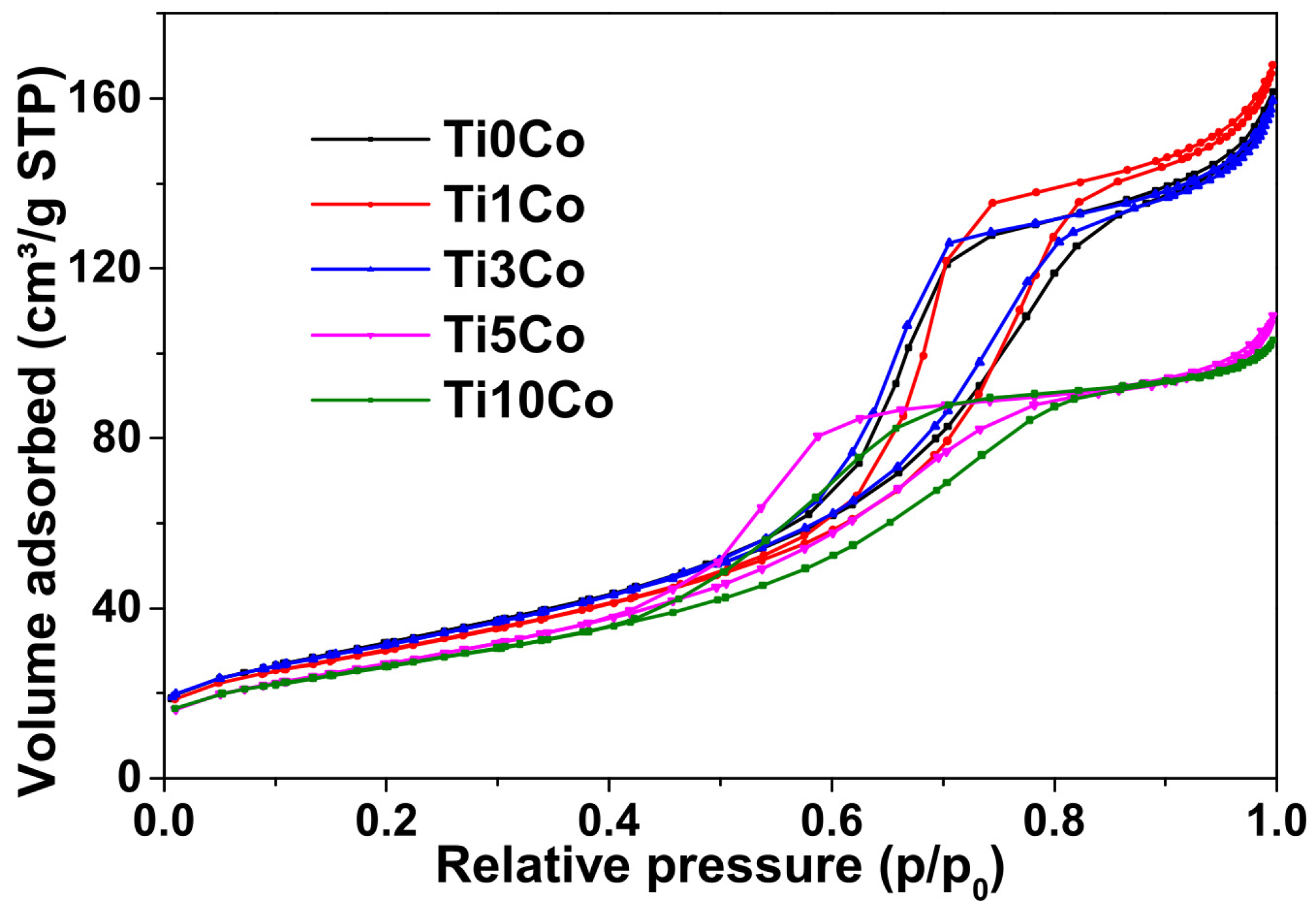

2.8. Textural Analysis (Specific Areas Determined by BET Method)

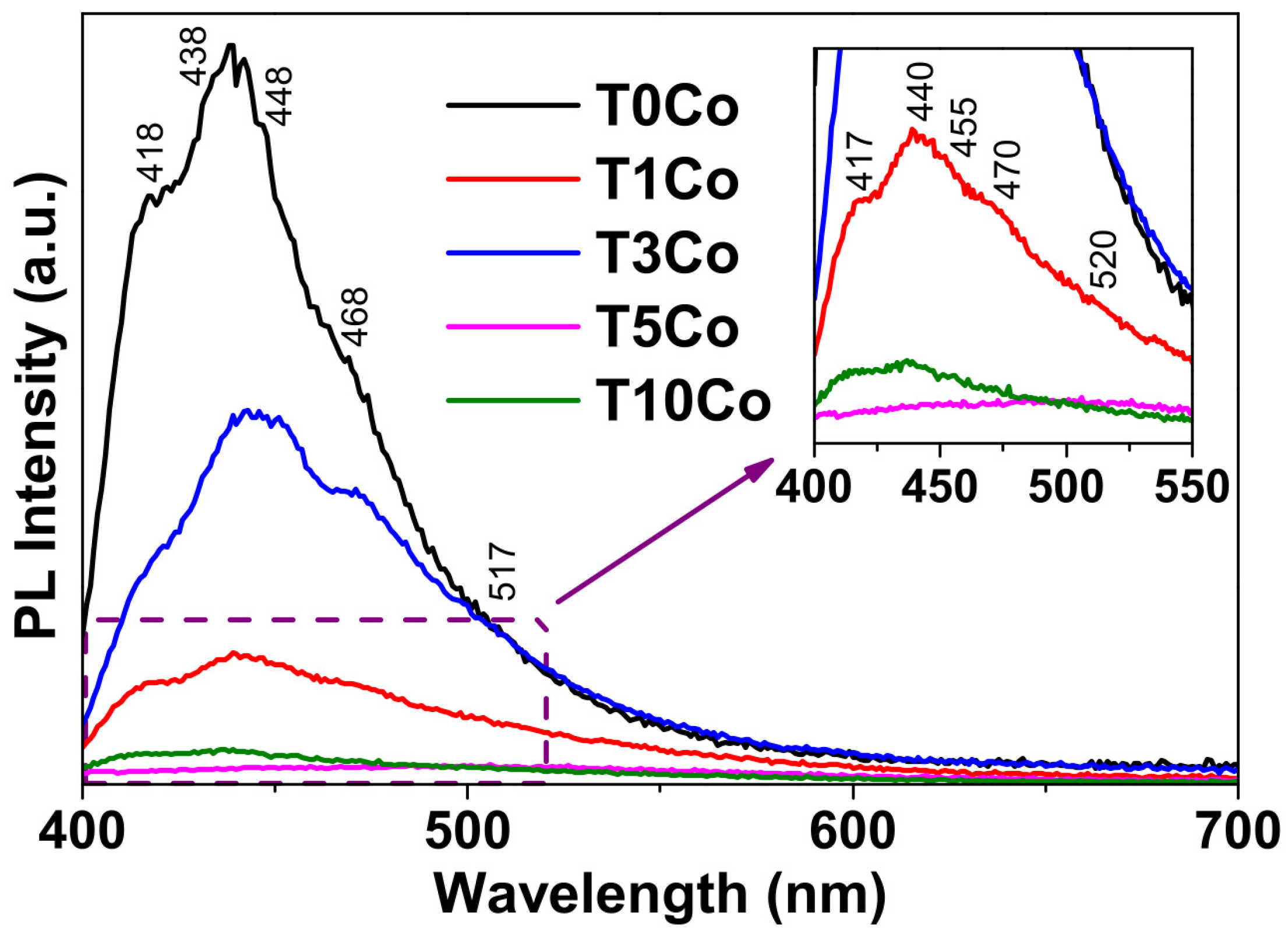

2.9. Photoluminescence (PL)

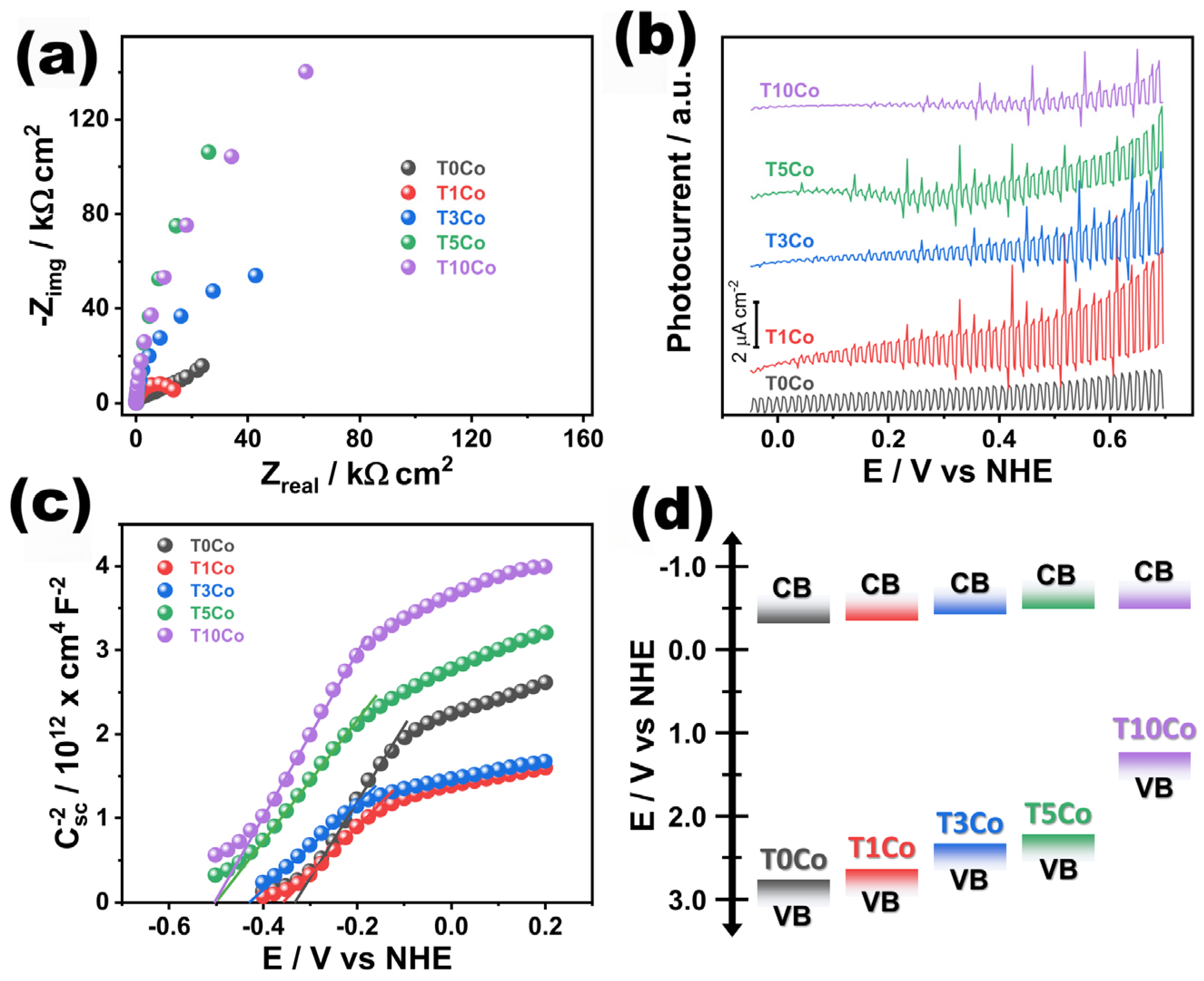

2.10. Electrochemical Tests

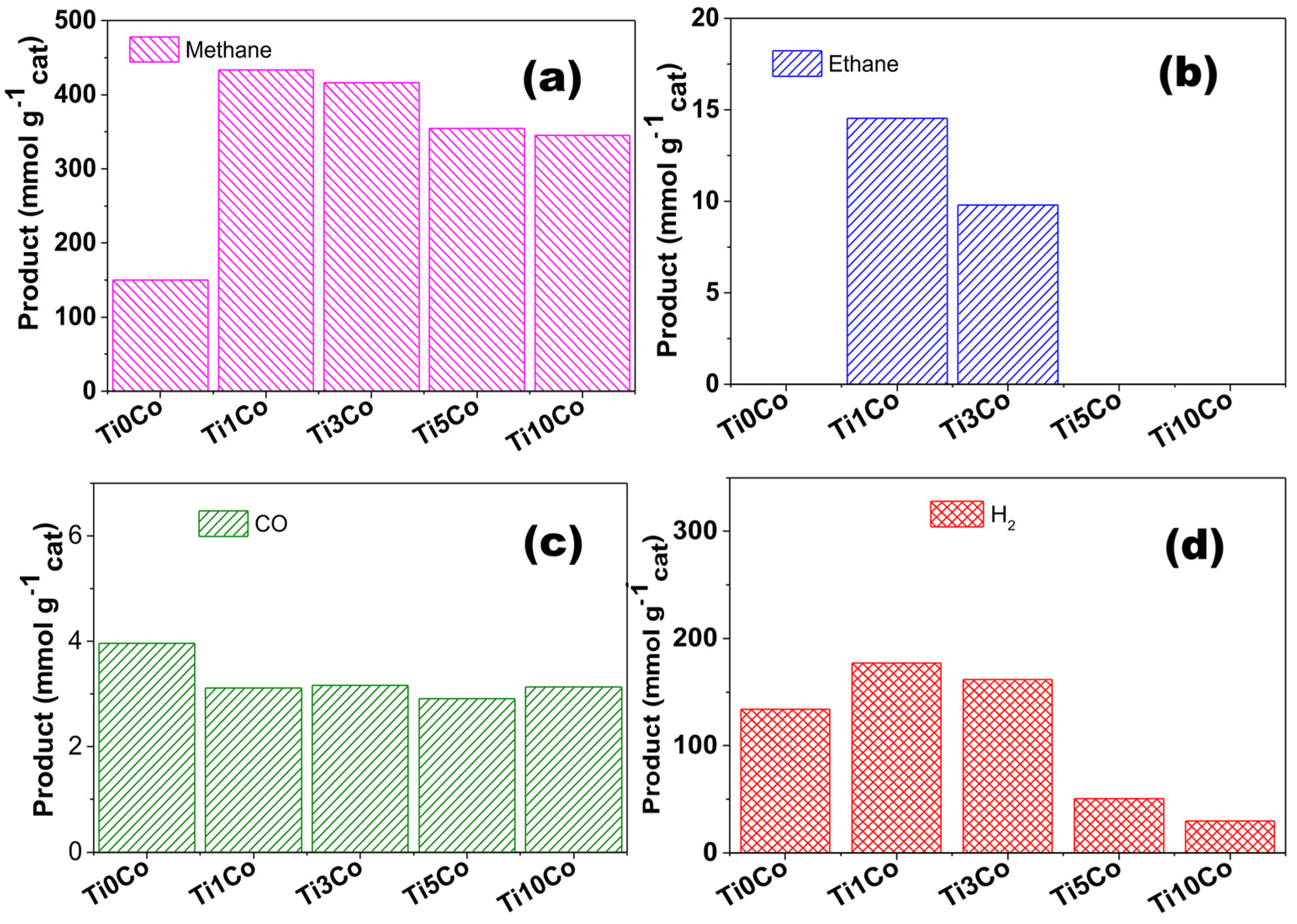

3. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction

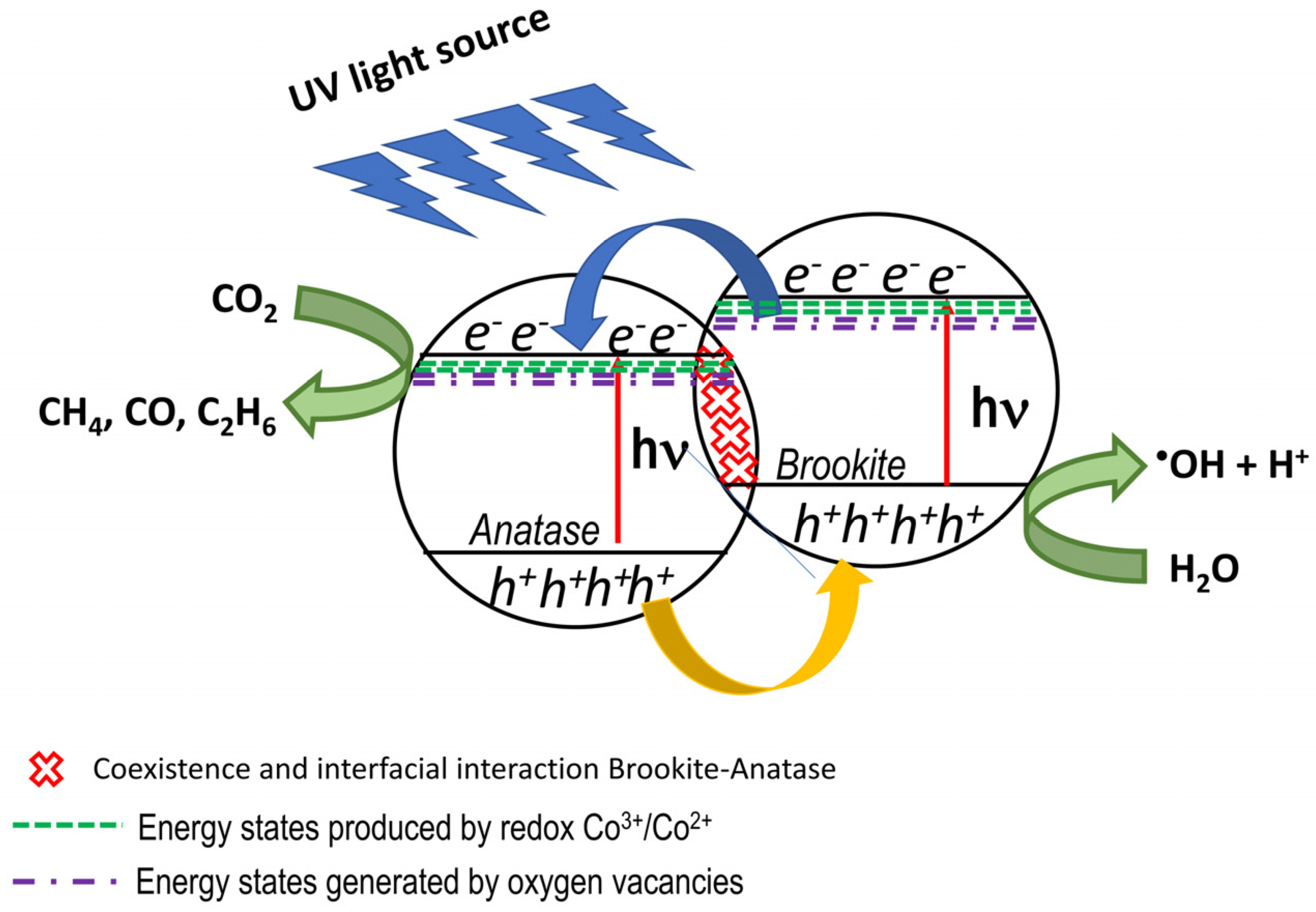

Proposed Reaction Mechanism

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of Nanomaterials

4.3. Physicochemical Characterization

4.4. Electrochemical Characterization

4.5. Photocatalytic Tests in CO2 Photoreduction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, T.; Hu, J.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, G.; Li, W.; Xiong, J. Oxygen Vacancy/Metallic Sites Synergically Assists Hollow TiO2–Induced CO2 Photoreduction: Categories and Roles. Fuel 2025, 385, 134107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Sheng, J.; Zhong, F.; He, Y.; Guro, V.P.; Sun, Y.; Dong, F. Rational Design and Mechanistic Insights of Advanced Photocatalysts for CO2 to C2+ Production: Status and Challenges. Chin. J. Catal. 2024, 60, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ng, D.; Du, H.; Hornung, C.H.; Polyzos, A.; Seeber, A.; Li, H.; Huo, Y.; Xie, Z. Copper Decorated Indium Oxide Rods for Photocatalytic CO2 Conversion under Simulated Sun Light. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 58, 101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.E.; Jin Kim, D.; Devthade, V.; Jo, W.K.; Tonda, S. Size-Dependent Selectivity and Activity of Highly Dispersed Sub-Nanometer Pt Clusters Integrated with P25 for CO2 Photoreduction into Methane Fuel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 584, 152532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.P.; Rangappa, A.P.; Shim, H.S.; Do, K.H.; Hong, Y.; Gopannagari, M.; Reddy, K.A.J.; Bhavani, P.; Reddy, D.A.; Song, J.K.; et al. Nanocavity-Assisted Single-Crystalline Ti3+ Self-Doped Blue TiO2 (B) as Efficient Cocatalyst for High Selective CO2 Photoreduction of g-C3N4. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 24, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Chen, F.; Yao, F.; Xie, T.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Li, X.; et al. Photocatalytic Conversion of Carbon Dioxide: From Products to Design the Catalysts. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Shen, M.; Wu, P.; Fu, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, L. A Distinctive Semiconductor-Metalloid Heterojunction: Unique Electronic Structure and Enhanced CO2 Photoreduction Activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 615, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, A.W.; Kusiak-Nejman, E.; Wanag, A.; Narkiewicz, U.; Edelmannová, M.; Reli, M.; Kočí, K. Influence of the Calcination of TiO2 Reduced Graphite Hybrid for the Photocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. Catal. Today 2021, 380, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Tahir, B. Dynamic Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to CO in a Honeycomb Monolith Reactor Loaded with Cu and N Doped TiO2 Nanocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 377, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permporn, D.; Khunphonoi, R.; Wilamat, J.; Khemthong, P.; Chirawatkul, P.; Butburee, T.; Sangkhun, W.; Wantala, K.; Grisdanurak, N.; Santatiwongchai, J.; et al. Insight into the Roles of Metal Loading on CO2 Photocatalytic Reduction Behaviors of TiO2. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricka, R.; Wanag, A.; Kusiak-Nejman, E.; Filip Edelmannová, M.; Reli, M.; Łapinski, M.; Słowik, G.; Morawski, A.W.; Kočí, K. Defective TiO2 for CO2 Photoreduction: Influence of Alkaline Agent and Reduction Temperature Modulation. Catal. Today 2025, 448, 115162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajji, L.A.; Ismail, A.A.; Alsaidi, M.; Nazeer, A.A.; El-Toni, A.M.; Al-Ruwayeh, S.F.; Ahmed, S.A.; Al-Sharrah, T. Fabrication of Mesoporous Sulfated ZnO-Modified g-C3N4 and TiO2 Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction in Gas Phase. Catal. Today 2025, 445, 115089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.-H.; Huang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chung, P.-W.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, H.-Y.; Liao, C.-N.; Chiu, E.-L.; Wang, C.-Y. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction for C2-C3 Oxy-Compounds on ZIF-67 Derived Carbon with TiO2. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 58, 101920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.K.; Iqbal, T. Critical Review on Modification of TiO2 for the Reduction of CO2. Res. Rev. J. Chem. 2018, 7, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, J.; Li, W.; Cheng, G. Lewis Base and Metallic Sites Cooperatively Promotes Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction in PO43−/Ag-TiO2 Hybrids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 130849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Lingampalli, S.R.; Ayyub, M.M.; Rao, C.N.R.; Larimi, A.; Rahimi, M.R.; Khorasheh, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; et al. Synergistic Effect of Surface and Bulk Single-Electron-Trapped Oxygen Vacancy of TiO2 in the Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 904, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, L.; Savitskiy, A.; Shtyka, O.; Maniecki, T.; Szynkowska-Jozwik, M.; Trifonov, A.; Pershina, E.; Mikhaylov, I.; Dubkov, S.; Gromov, D. Formation of Cu-Rh Alloy Nanoislands on TiO2 for Photoreduction of Carbon Dioxide. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 904, 164012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, F.; Zhu, S.; Xu, Y.; Liang, Q.; Chen, Z. Controlled Charge-Dynamics in Cobalt-Doped TiO2 Nanowire Photoanodes for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 530, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, T.G.; de Oliveira, A.H.; da Silva, L.O.; Santana, M.d.V.; Nascimento, J.S.; de Abreu, G.J.P.; Guerra, Y.; Garcia, R.R.P.; dos Santos, F.E.P.; Viana, B.C. A Comprehensive Study of Structural, Optical, and Magnetic Properties of Co and Fe-Doped TiO2 Prepared by Different Sol-Gel Routes. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 116, 2670–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalyavka, T.O.; Shymanovska, V.V.; Gavrilko, T.A.; Manuilov, E.V.; Klishevich, G.V.; Szymański, D.; Chaika, M.; Bezkrovnyi, O.; Baran, J.; Drozd, M.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanostructured Co-Si Co-Doped TiO2 with Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Performance in Phenol Red Degradation. Ceram. Int. 2026, 52, 1221–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Yao, S.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Q.; Lin, R.; Liang, D.; Shen, D. Cobalt-Doped Rutile/Anatase TiO2 Photoanode with Oriented Energy Band Offset for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 700, 163159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Leal, E.L.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Güiza-Argüello, V.R.; Córdoba-Tuta, E.M. N and F, Co doped TiO2 Thin Films on Stainless Steel for Photoelectrocatalytic Removal of Cyanide Ions in Aqueous Solutions. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A.; Rout, K.; Vasundhara, M.; Joshi, S.R.; Singh, J. Structural and Magnetic Study of Undoped and Cobalt Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10939–10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.; Guo, R.T.; Pan, W.G.; Tang, J.Y.; Zhou, W.G.; Qin, H.; Liu, X.Y.; Jia, P.Y. Eu-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles with Enhanced Activity for CO2 Phpotcatalytic Reduction. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 26, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Y.; Nguyen, N.H.; Bai, H.; Chang, S.M.; Wu, J.C.S. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 Using Molybdenum-Doped Titanate Nanotubes in a MEA Solution. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 63142–63151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Meng, X.; Liu, G.; Chang, K.; Li, P.; Kang, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, M.; Ouyang, S.; Ye, J. In Situ Synthesis of Ordered Mesoporous Co-Doped TiO2 and Its Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and Selectivity for the Reduction of CO2. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2015, 3, 9491–9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.A.; da Cruz, J.C.; Nogueira, A.E.; da Silva, G.T.S.T.; de Oliveira, J.A.; Ribeiro, C. Role of Cu0-TiO2 Interaction in Catalyst Stability in CO2 Photoreduction Process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgolombane, M.; Bankole, O.M.; Ferg, E.E.; Ogunlaja, A.S. Construction of Co-Doped TiO2/RGO Nanocomposites for High-Performance Photoreduction of CO2 with H2O: Comparison of Theoretical Binding Energies and Exploration of Surface Chemistry. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 268, 124733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Sharma, S.N.; Kumar, M.; De, S.K. Morphology Dependent Luminescence Properties of Co Doped TiO2 Nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 14783–14792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, M.S.; Lassoued, A.; Ammar, S.; Gadri, A.; Salah, A.B.; García-Granda, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Co-Doped Nano-TiO2 through Co-Precipitation Method for Photocatalytic Activity. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 8914–8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshay, V.R.; Arun, B.; Mandal, G.; Mutta, G.R.; Chanda, A.; Vasundhara, M. Observation of Optical Band-Gap Narrowing and Enhanced Magnetic Moment in Co-Doped Sol-Gel-Derived Anatase TiO2 Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 26592–26604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, B.; Choudhury, A. Luminescence Characteristics of Cobalt Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles. J. Lumin. 2012, 132, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhapara, K.; Shah, D. Characterization of Nanocrystalline Cobalt Doped TiO2 Sol-Gel Material. J. Cryst. Growth 2012, 352, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mragui, A.; Zegaoui, O.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Elucidation of the Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism of an Azo Dye under Visible Light in the Presence of Cobalt Doped TiO2 Nanomaterials. Chemosphere 2021, 266, 128931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, S.; Tanaka, A.; Murata, A.; Sakurada, T. Formulation for XPS Spectral Change of Oxides by Ion Bombardment as a Function of Sputtering Time. Surf. Sci. 2004, 556, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counsell, J.D.P.; Roberts, A.J.; Boxford, W.; Moffitt, C.; Takahashi, K. Reduced Preferential Sputtering of TiO2 Using Massive Argon Clusters. J. Surf. Anal. 2014, 20, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, R.J.; Gaikwad, P.V.; Garadkar, K.M.; Sabale, S.R.; Puri, V.R.; Mahajan, S.S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Malachite Green Using Hydrothermally Synthesized Cobalt-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2022, 19, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-G.; Büchel, R.; Isobe, M.; Mori, T.; Ishigaki, T. Cobalt-Doped TiO2 Nanocrystallites: Radio-Frequency Thermal Plasma Processing, Phase Structure, and Magnetic Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 8009–8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadanandam, G.; Lalitha, K.; Kumari, V.D.; Shankar, M.V.; Subrahmanyam, M. Cobalt Doped TiO2: A Stable and Efficient Photocatalyst for Continuous Hydrogen Production from Glycerol: Water Mixtures under Solar Light Irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 9655–9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, C.; Pandey, O.P.; Chudasama, B. Synthesis of Visible Light-Responsive Cobalt-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles with Tunable Optical Band Gap. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2015, 75, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Xiang, W.; Kuang, J.; Liu, W.; Cao, W. Effect of Cobalt Doping on the Electronic, Optical and Photocatalytic Properties of TiO2. Solid State Sci. 2015, 46, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chu, W. Cooperation of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Cobalt Doped TiO2 to Activate Peroxymonosulfate for Antipyrine Photocatalytic Degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 282, 119996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mragui, A.; Zegaoui, O.; Daou, I.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Preparation, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity under UV and Visible Light of Co, Mn, and Ni Mono-Doped and (P,Mo) and (P,W) Co-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles: A Comparative Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 28, 25130–25145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindhya, P.S.; Suresh, S.; Kavitha, V.T. Annona Muricata Leaf Extract Mediated Synthesis of Pure and Co Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles: Evaluation of Catalytic Reduction, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 103, 766–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y. Understanding the Reaction Mechanism of Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with H2O on TiO2-Based Photocatalysts: A Review. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompsett, G.A.; Bowmaker, G.A.; Cooney, R.P.; Metson, J.B.; Rodgers, K.A.; Seakins, J.M. The Raman Spectrum of Brookite, TiO2 (Pbca, Z = 8). J. Raman Spectrosc. 1995, 26, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, S.; Jin, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, J.; Peng, T. Brookite TiO2 Nanoparticles Decorated with Ag/MnOx Dual Cocatalysts for Remarkably Boosted Photocatalytic Performance of the CO2 Reduction Reaction. Langmuir 2021, 37, 12487–12500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugundan, S.; Rajamannan, B.; Viruthagiri, G.; Shanmugam, N.; Gobi, R.; Praveen, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Undoped and Cobalt-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles via Sol–Gel Technique. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 5, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, F.; Al-Jaml, K.L.; Bhosale, R.R. Solar Photo-Catalytic Production of Hydrogen by Irradiation of Cobalt Co-Doped TiO2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 12068–12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W.; Everett, D.H.; Haul, R.A.W.; Moscou, L.; Pierotti, R.S.; Rouquerol, J.; Siemieniewska, T. International Union of Pure Commission on Colloid and Surface Chemistry including catalysis Reporting Physisorption Data for Gas/Solid Systems with Special Reference to the Determination of Surface Area and Porosity. Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.M.; Ahmed, A.I.; Mannaa, M.A. Preparation and Characterization of SnO2 Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles: Effect of Phase Changes on the Photocatalytic and Catalytic Activity. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2019, 4, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnol, V.; Sutter, E.; Debiemme-Chouvy, C.; Cachet, H.; Baroux, B. EIS Study of Photo-Induced Modifications of Nano-Columnar TiO2 Films. Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 1228–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, L.; Valencia, K.; Hernández-Gordillo, A.; Bizarro, M.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Rodil, S.E. Increasing the H2 Production Rate of ZnS(En)x Hybrid and ZnS Film by Photoexfoliation Process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 22403–22414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Song, Q.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, D. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 into CH4 over Ru-Doped TiO2: Synergy of Ru and Oxygen Vacancies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 608, 2809–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, B.; Gong, X.; Duan, A.; Liu, J.; et al. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with Water Vapor on Surface La-Modified TiO2 Nanoparticles with Enhanced CH4 Selectivity. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 168–169, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.A.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Mohamed, A.R. Visible Light Responsive TiO2 Nanoparticles Modified Using Ce and La for Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2: Effect of Ce Dopant Content. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 537, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, S.; Amin, N.A.S.; Ghaedi, M. Photocatalytic Conversion and Kinetic Study of CO2 and CH4 over Nitrogen-Doped Titania Nanotube Arrays. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Luo, S.; Su, W.; Wang, X. Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction with H2O over LaPO4 Nanorods Deposited with Pt Cocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 168–169, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y. Promotion of Multi-Electron Transfer for Enhanced Photocatalysis: A Review Focused on Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 358, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Vázquez, I.; Del Angel, G.; Ramos-Ramírez, E.; González, F.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Gómez, C.M.; Tzompantzi, F.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, N.; Torres-Torres, J.G. Improvement of Photocatalytic Activity in the Degradation of 4-Chlorophenol and Phenol in Aqueous Medium Using Tin-Modified TiO2 Photocatalysts. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13862–13879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Anatase | Brookite | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Parameters (nm) | Crystal Size (nm) | Relative Phase Conc. wt(%) | Volume Unit Cell (Å3) | Cell Parameters (nm) | Crystal Size (nm) | Relative Phase Conc. wt(%) | Volume Unit Cell (Å3) | ||||

| Sample | a | c | a | b | c | ||||||

| Ti0Co | 0.37891 (3) * | 0.94908 (1) | 11.9 (6) * | 78.2 (3) * | 136.26 | 0.92020 (5) * | 0.54365 (3) | 0.51828 (2) | 9.0 (2) * | 21.7 (3) * | 259.28 |

| Ti1Co | 0.37906 (3) | 0.94810 (1) | 10.4 (6) | 81.1 (4) | 136.22 | 0.91892 (8) | 0.54338 (5) | 0.52032 (3) | 8.6 (2) | 18.8 (3) | 259.80 |

| Ti3Co | 0.37927 (4) | 0.94752 (1) | 9.5 (6) | 80.8 (4) | 136.29 | 0.91793 (9) | 0.54419 (6) | 0.52033 (4) | 8.0 (2) | 19.9 (4) | 259.92 |

| Ti5Co | 0.37928 (4) | 0.94853 (1) | 10.6 (7) | 82.4 (5) | 136.44 | 0.91775 (1) | 0.54460 (8) | 0.52056 (6) | 7.0 (3) | 17.5 (5) | 260.18 |

| Ti10Co | 0.37969 (5) | 0.94799 (1) | 9.3 (7) | 79.3 (6) | 136.66 | 0.91471 (1) | 0.54463 (8) | 0.52365 (7) | 6.9 (2) | 20.7 (6) | 260.87 |

| Ti 2p3/2 | Co 2p3/2 | O 1s | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy (eV) | |||||||||

| Sample | Ti4+ | Ti3+ | TixOy | Co3+ | Co2+ | OLatt | OSurf | Ovac | |

| Anatase | Brookite | ||||||||

| Ti0Co | 458.7 | 458.5 | 456.9 | - | - | - | 530.1 | 531.7 | - |

| (77.3) * | (3.7) * | (19.0) * | - | - | - | (89.2) * | (10.8) * | - | |

| Ti1Co | 458.5 | 458.3 | 456.8 | - | 782.9 | 781.9 | 530.0 | 531.4 | 531.0 |

| (74.9) | (5.9) | (19.2) | - | (29) | (71) | (88.7) | (10.2) | (1.1) | |

| Ti3Co | 458.5 | 458.3 | 456.9 | 459.9 | 782.8 | 781.7 | 529.8 | 530.8 | 531.8 |

| (48.2) | (9.3) | (19.8) | (22.7) | (30.5) | (69.5) | (58.1) | (21.3) | (20.6) | |

| Ti5Co | 458.3 | 458.2 | 456.6 | 459.6 | 782.7 | 780.8 | 529.4 | 530.2 | 531.1 |

| (65.2) | (17.8) | (5.1) | (11.9) | (36.7) | (63.3) | (62.7) | (15.8) | (21.5) | |

| Ti10Co | 458.1 | 458.0 | 456.6 | 459.5 | 782.4 | 780.7 | 529.2 | 529.7 | 530.6 |

| (59.5) | (22.9) | (2.4) | (15.2) | (31.5) | (68.5) | (49.8) | (19.7) | (30.5) | |

| Sample | BET Surface Area (m2g−1) | Average Pore Diameter (nm) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Band Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti0Co | 114.8 | 15.2 | 0.323 | 3.16 |

| Ti1Co | 116.5 | 4.6 | 0.149 | 2.98 |

| Ti3Co | 110.5 | 4.5 | 0.110 | 2.85 |

| Ti5Co | 99.5 | 4.7 | 0.096 | 2.78 |

| Ti10Co | 95.6 | 7.2 | 0.313 | 2.22 |

| Sample | Methane (mmol g−1cat) | Ethane (mmol g−1cat) | CO (mmol g−1cat) | H2 (mmol g−1cat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti0Co | 150.2 | - | 3.9 | 140.1 |

| Ti1Co | 440.0 | 14.6 | 3.1 | 177.0 |

| Ti3Co | 416.5 | 9.8 | 3.0 | 161.5 |

| Ti5Co | 354.8 | - | 2.9 | 50.5 |

| Ti10Co | 345.2 | - | 3.2 | 29.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rangel-Vázquez, I.; Ramos-Ramírez, E.; Angel, G.D.; Huerta, L.; González, F.; Acevedo-Peña, P.; Nolasco-Guerrero, D.; Gómez, C.M.; Palacios-González, E.; Díaz, M.C. Production of Methane and Ethane with Photoreduction of CO2 Using Nanomaterials of TiO2 (Anatase–Brookite) Modifications with Cobalt. Catalysts 2026, 16, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020146

Rangel-Vázquez I, Ramos-Ramírez E, Angel GD, Huerta L, González F, Acevedo-Peña P, Nolasco-Guerrero D, Gómez CM, Palacios-González E, Díaz MC. Production of Methane and Ethane with Photoreduction of CO2 Using Nanomaterials of TiO2 (Anatase–Brookite) Modifications with Cobalt. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020146

Chicago/Turabian StyleRangel-Vázquez, Israel, Esthela Ramos-Ramírez, G. Del Angel, L. Huerta, F. González, Próspero Acevedo-Peña, Diana Nolasco-Guerrero, Claudia M. Gómez, E. Palacios-González, and Marina Caballero Díaz. 2026. "Production of Methane and Ethane with Photoreduction of CO2 Using Nanomaterials of TiO2 (Anatase–Brookite) Modifications with Cobalt" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020146

APA StyleRangel-Vázquez, I., Ramos-Ramírez, E., Angel, G. D., Huerta, L., González, F., Acevedo-Peña, P., Nolasco-Guerrero, D., Gómez, C. M., Palacios-González, E., & Díaz, M. C. (2026). Production of Methane and Ethane with Photoreduction of CO2 Using Nanomaterials of TiO2 (Anatase–Brookite) Modifications with Cobalt. Catalysts, 16(2), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020146