Mechanism and Performance of Melamine-Based Metal-Free Organic Polymers with Modulated Nitrogen Structures for Catalyzing CO2 Cycloaddition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

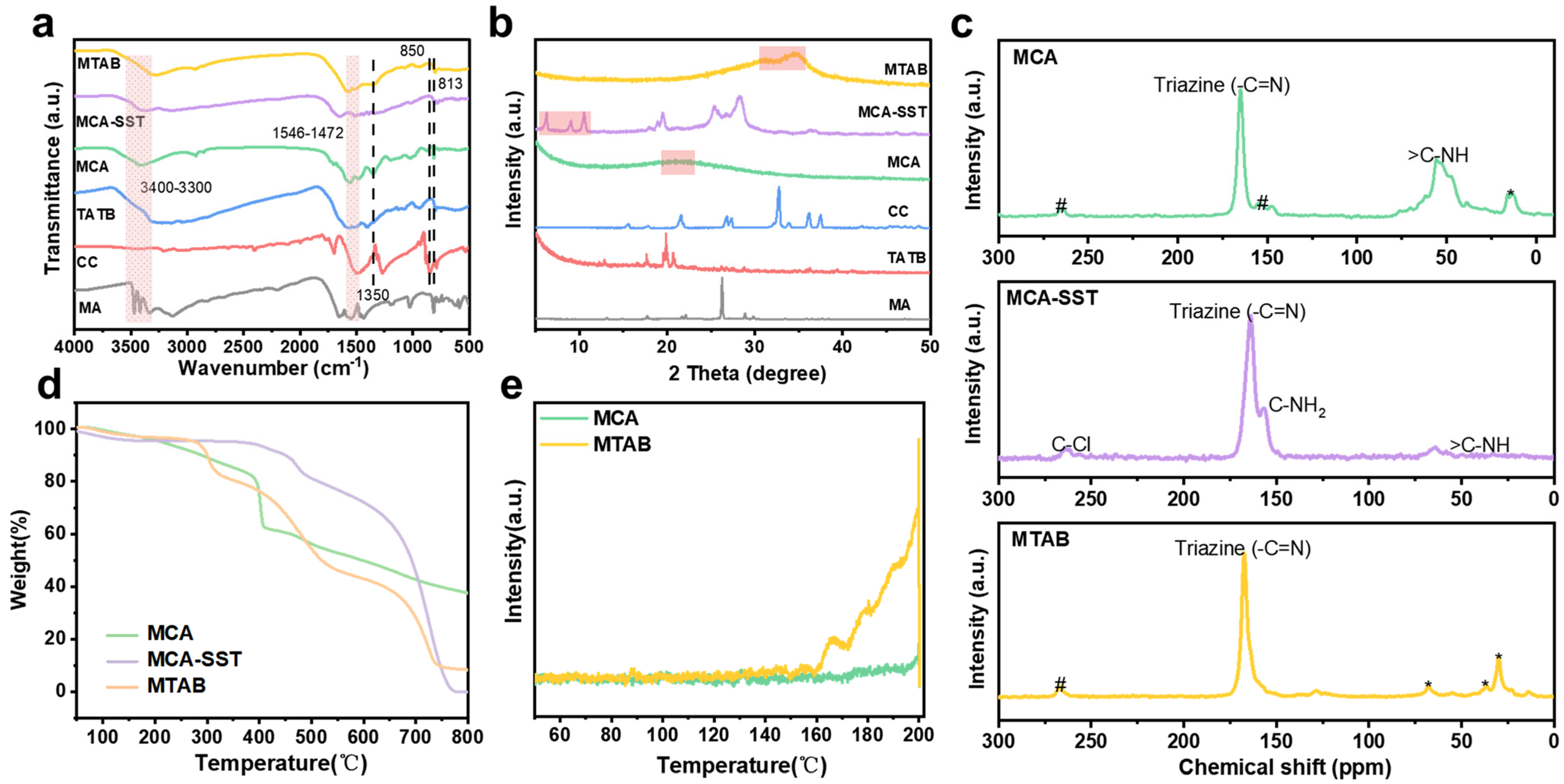

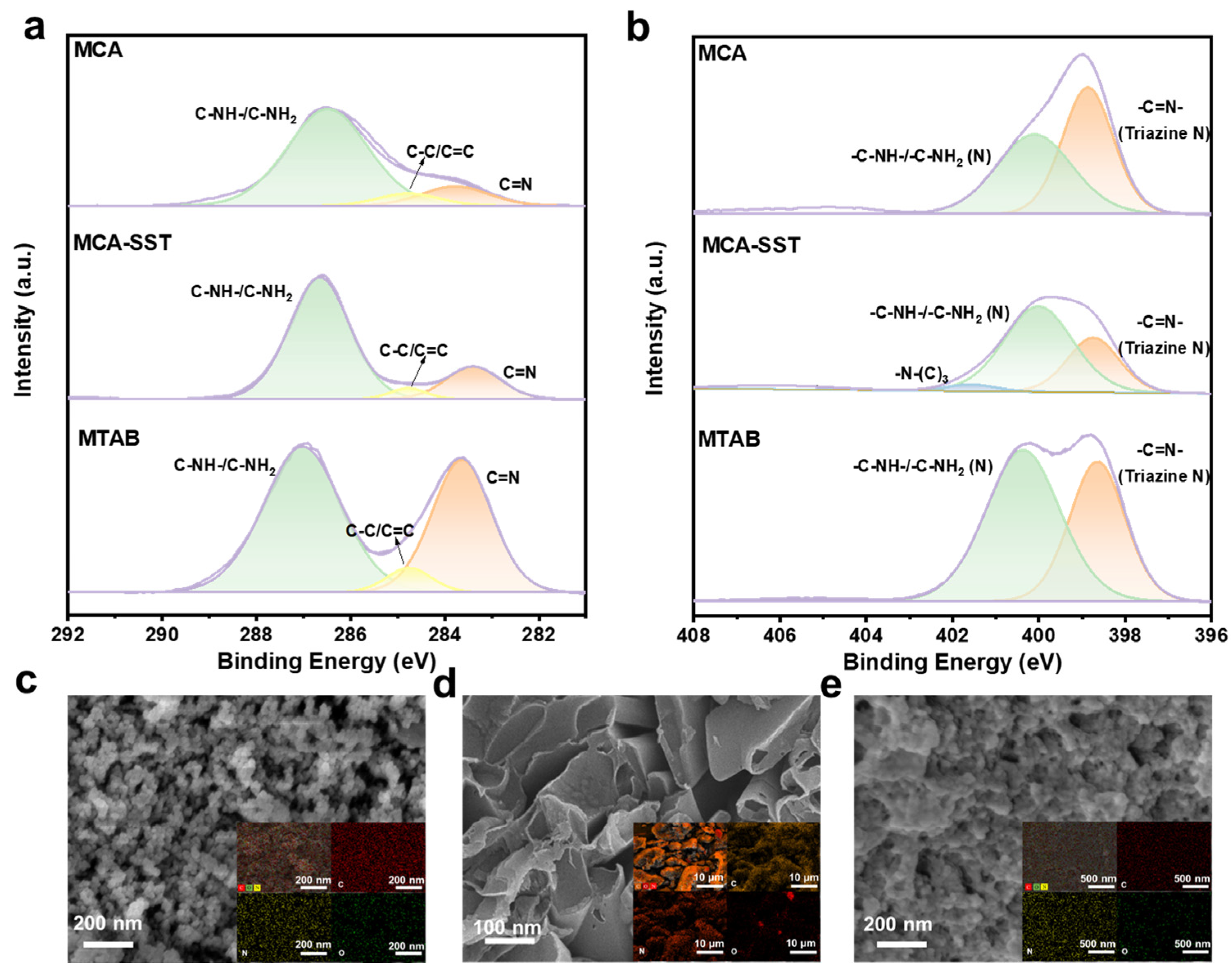

2.1. Analysis of Material Characterization Results

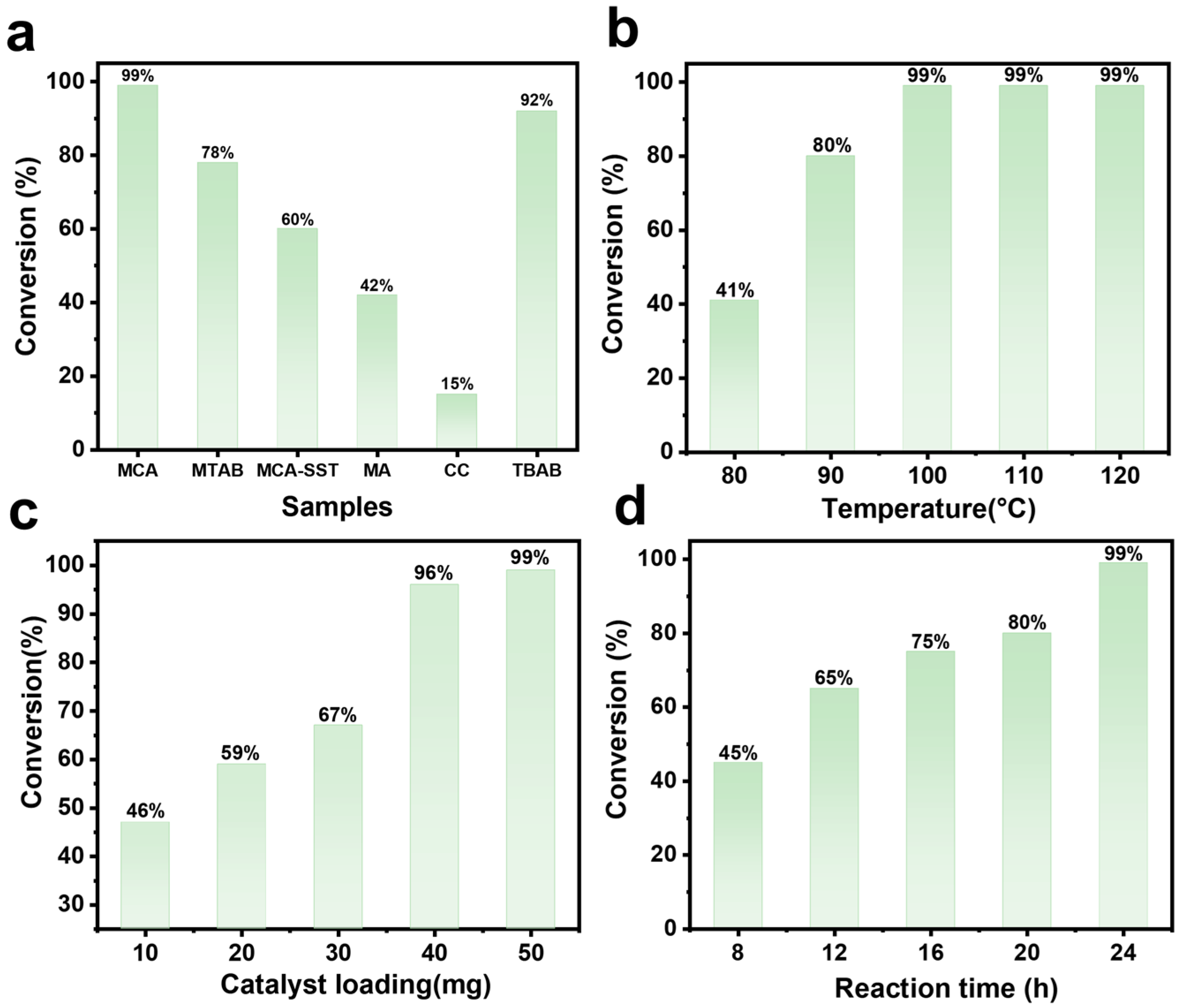

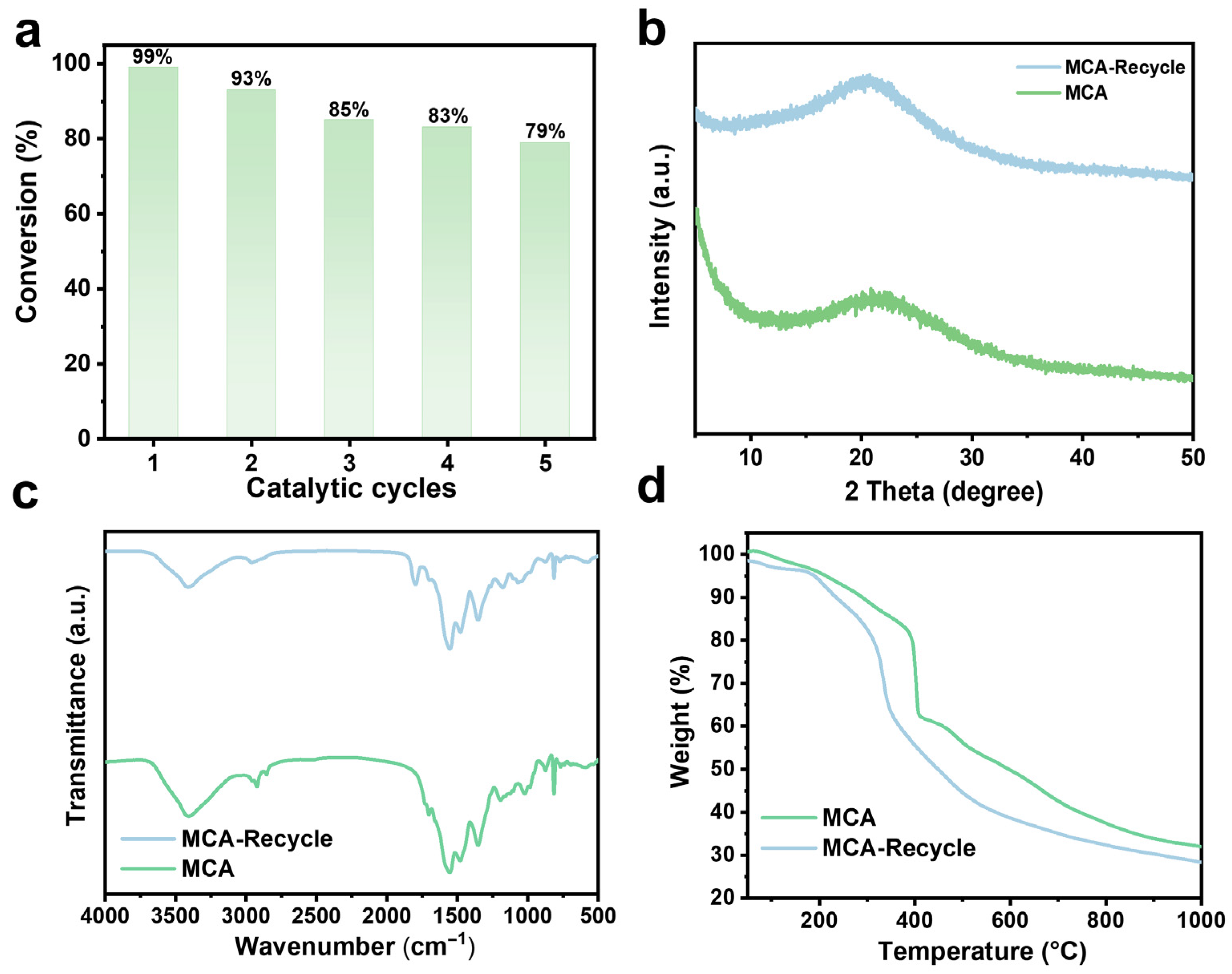

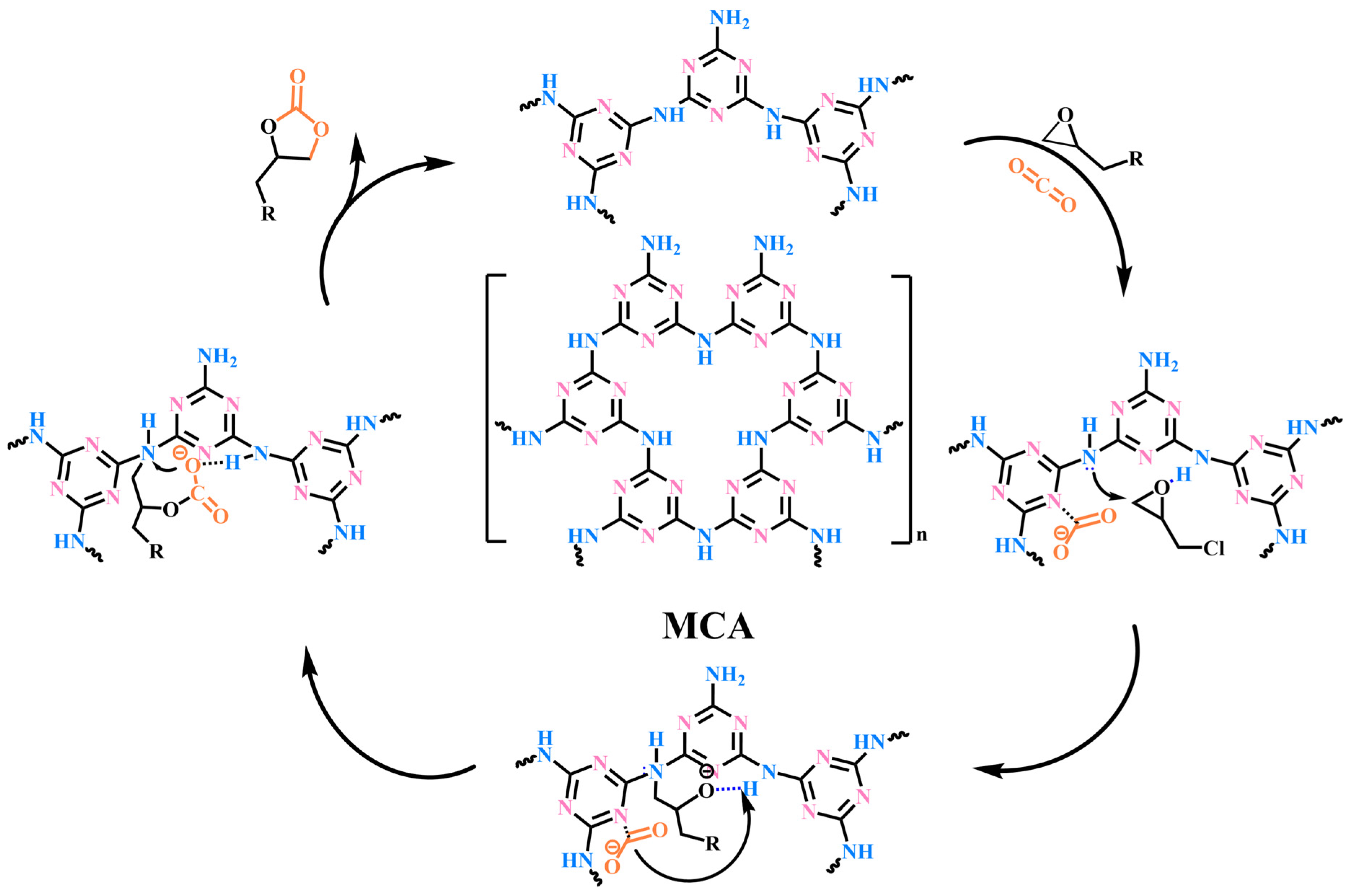

2.2. Ring-Addition Catalytic Activity of MCA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Chemical Reagents

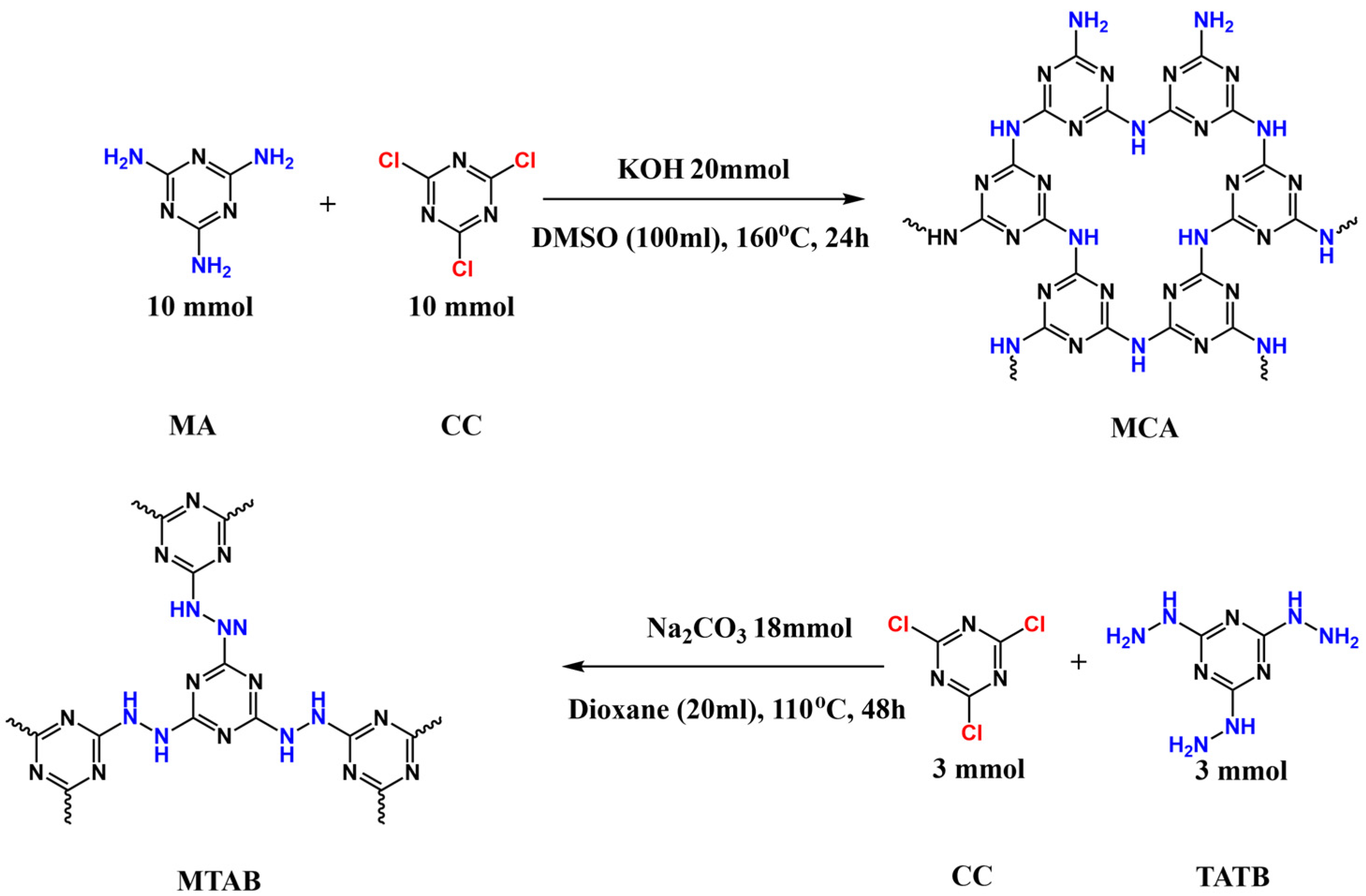

3.2. Synthesis

3.3. Catalytic Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Artz, J.; Müller, T.E.; Thenert, K.; Kleinekorte, J.; Meys, R.; Sternberg, A.; Bardow, A.; Leitner, W. Sustainable Conversion of Carbon Dioxide: An Integrated Review of Catalysis and Life Cycle Assessment. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 434–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, L.; Jackstell, R.; Beller, M. Using Carbon Dioxide as a Building Block in Organic Synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Pan, S.-Y.; Li, H.; Cai, J.; Olabi, A.G.; Anthony, E.J.; Manovic, V. Recent Advances in Carbon Dioxide Utilization. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2020, 125, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wu, Q.; Cao, R. Reticular Frameworks and Their Derived Materials for CO2 Conversion by Thermo-catalysis. EnergyChem 2021, 3, 100064. [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn, C.; Adlen, E.; Beddington, J.; Carter, E.A.; Fuss, S.; Dowell, N.M.; Min, J.C.; Smith, P.; Williams, C.K. The Technological and Economic Prospects for CO2 Utilization and Removal. Nature 2019, 575, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, P.; Singh, D.; Malik, N.; Kumar, S.; Malik, R.S. Metal Catalyst for CO2 Capture and Conversion into Cyclic Carbonate: Progress and Challenges. Mater. Today 2023, 65, 133–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Lamb, K.J.; North, M. Recent Developments in Organocatalysed Transformations of Epoxides and Carbon Dioxide into Cyclic Carbonates. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 77–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Saleem, F.; Javed, F.; Ikhlaq, A.; Ahmad, S.W.; Harvey, A. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates via CO2 Cycloaddition to Epoxides. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.; Srivastava, V.C. Synthesis of Organic Carbonates from Alcoholysis of Urea: A Review. Catal. Rev. 2017, 59, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescarmona, P.P. Cyclic Carbonates Synthesised from CO2: Applications, Challenges and Recent Research Trends. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 29, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.C. Cyclic Carbonate Functional Polymers and Their Applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2003, 47, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Maynard, E.; Chiaradia, V.; Arnό, M.C.; Dove, A.P. Aliphatic Polycarbonates from Cyclic Carbonate Monomers and Their Application as Biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10865–10907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaravel, V.; Bartlett, J.; Pillai, S.C. Photoelectrochemical Conversion of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) into Fuels and Value-Added Products. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 486–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ma, T.; Tao, H.; Fan, Q.; Han, B. Fundamentals and Challenges of Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Using Two-Dimensional Materials. Chem 2017, 3, 560–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Long, R.; Gao, C.; Xiong, Y. Recent Progress on Advanced Design for Photoelectrochemical Reduction of CO2 to Fuels. Sci. China Mater. 2018, 61, 771–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, I. Conversion of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol Using Solar Energy—A Brief Review. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2011, 2, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Ding, F.; Zhang, A.; Guo, X.; Song, C. CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol over In2O3-Based Catalysts: From Mechanism to Catalyst Development. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Heard, A.W.; Suárez, J.M.; Goldup, S.M. Controlling Catalyst Activity, Chemoselectivity and Stereoselectivity with the Mechanical Bond. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debruyne, M.; Van Speybroeck, V.; Van Der Voort, P.; Stevens, C.V. Porous Organic Polymers as Metal Free Heterogeneous Organocatalysts. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 7361–7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wen, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ning, P.; Chen, Y.; Hao, J. Progress in Reaction Mechanisms and Catalyst Development of Ceria-Based Catalysts for Low-Temperature CO2 Methanation. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, H.; Wang, K.Y.; Powell, J.A.; ZareKarizi, F.; Lv, X.-L.; Morsali, A.; Zhou, H.-C. Metal-Organic Frameworks Based on Multicarboxylate Linkers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 426, 213542. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M.; Iqbal, N.; Noor, T.; Zaman, N.; Asghar, A.; Abdelnaby, M.M.; Galadima, A.; Helal, A. Advanced Strategies in Metal-Organic Frameworks for CO2 Capture and Separation. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202100230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Comerford, J.W.; Ingram, I.D.V.; North, M.; Wu, X. Sustainable Metal-Based Catalysts for the Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates Containing Five-Membered Rings. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1966–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, N.; Yadav, S.; Singh, L.; Rekha, P. Metal Phosphonates Find Their Way for CO2 Cycloaddition: A Mini-Review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 156, 111220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Tan, X.; Luo, T.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Han, B. Solvent Impedes CO2 Cycloaddition on Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tran, C.H.; Choi, H.K.; Yu, D.-G.; Kim, I. Porous Organic Polymers with Defined Morphologies: Synthesis, Assembly, and Emerging Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 142, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.-H. Implanting Multi-Functional Ionic Liquids into MOF Nodes for Boosting CO2 Cycloaddition under Solventless and Cocatalyst-Free Conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Hydroxyl-Imidazolium Ionic Liquid-Functionalized MIL-101(Cr): A Bifunctional and Highly Efficient Catalyst for the Conversion of CO2 to Styrene Carbonate. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 17438–17447. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhao, J.; Shi, L. Promotion Mechanism of Hydroxyl Groups in Catalyzing CO2 Cycloaddition. J. CO2 Util. 2025, 91, 102999. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Hu, T.; Zhao, W.; Su, H.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Triazinyl-Imidazole Polyamide Network as an Efficient Multi-Hydrogen Bond Donor Catalyst for Additive-Free CO2 Cycloaddition. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2022, 643, 118748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.; Pasquale, R.; Young, C. Synthesis of Cyclic Carbonates from Epoxides and CO2. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 1514–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Ma, X.; Su, Q.; Liu, L.; Ying, T.; Qian, W.; Dong, L.; Cheng, W. Hydrogen Bond Donor Functionalized Poly(Ionic Liquid)s for Efficient Synergetic Conversion of CO2 to Cyclic Carbonates. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ping, R.; He, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F.; Chen, H.; Yu, S.; Gao, K.; Liu, M. Unveiling the Incorporation of Dual Hydrogen-Bond-Donating Squaramide Moieties into Covalent Triazine Frameworks for Promoting Low-Concentration CO2 Fixation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 365, 124895. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, Y.Z.; Liu, X.L.; Du, G.J.; Yan, S.H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z. A Hydroxyl-Functionalized Microporous Organic Polymer for Capture and Catalytic Conversion of CO2. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 76957–76963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Hu, T.; Pudukudy, M.; Shi, L.; Shan, S.; Zhi, Y. Modified Melamine-Based Porous Organic Polymers with Imidazolium Ionic Liquids as Efficient Heterogeneous Catalysts for CO2 Cycloaddition. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 652, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Zou, B.; Yang, G.P.; Yu, B.; Hu, C.W. Melamine-Based Mesoporous Organic Polymers as Metal-Free Heterogeneous Catalyst: Effect of Hydroxyl on CO2 Capture and Conversion. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 22, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Xiang, X.; Sang, Y.; Huang, J. Melamine-Supported Porous Organic Polymers for Efficient CO2 Capture and Hg2+ Removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387, 124070. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Lombardo, L.; Tsujimoto, M.; Fan, Z.; Berdichevsky, E.K.; Wei, Y.-S.; Kageyama, K.; Nishiyama, Y.; Horike, S. Synthesizing Interpenetrated Triazine-Based Covalent Organic Frameworks from CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 135, e202312095. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Hu, T.; Shi, L.; Pudukudy, M.; Shan, S.; Zhi, Y. Urea/Amide-Functionalized Melamine-Based Organic Polymers as Efficient Heterogeneous Catalysts for CO2 Cycloaddition. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145918. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Pudukudy, M.; Lin, L.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Shan, S.; Hu, T.; Zhi, Y. Melamine-Based Nitrogen-Heterocyclic Polymer Networks as Efficient Platforms for CO2 Adsorption and Conversion. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125645. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.; Wen, M.; Fan, C.; Lin, S.; Pan, Q. Melamine-Based Porous Organic Polymers Supported Pd(II)-Catalyzed Addition of Arylboronic Acids to Aromatic Aldehydes. Catal. Lett. 2021, 151, 2612–2621. [Google Scholar]

- Mariyaselvakumar, M.; Kadam, G.G.; Saha, A.; Samikannu, A.; Mikkola, J.-P.; Ganguly, B.; Srinivasan, K.; Konwar, L.J. Halogenated Melamine Formaldehyde Polymers: Efficient, Robust and Cost-Effective Bifunctional Catalysts for Continuous Production of Cyclic Carbonates via CO2-Epoxide Cycloaddition. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2024, 675, 119634. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhasivam, V.; Harikrishnan, M.; Elamathi, G.; Balasaravanan, R.; Murugesan, S.; Siva, A. Copper Nanoparticles Supported on Highly Nitrogen-Rich Covalent Organic Polymers as Heterogeneous Catalysts for the Ipso-Hydroxylation of Phenyl Boronic Acid to Phenol. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 6222–6231. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Zhang, J.; Lv, X. Novel Hydrazine-Bridged Covalent Triazine Polymer for CO2 Capture and Catalytic Conversion. Chin. J. Catal. 2018, 39, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wen, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhao, R.; Yang, S. Pre-Carbonized Nitrogen-Rich Polytriazines for the Controlled Growth of Silver Nanoparticles: Catalysts for Enhanced CO2 Chemical Conversion at Atmospheric Pressure. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 3119–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.; Muhammad, R.; Ramachandran, C.N.; Mohanty, P. Nitrogen Amelioration-Driven Carbon Dioxide Capture by Nanoporous Polytriazine. Langmuir 2019, 35, 4893–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ping, R.; Lu, X.; Shi, H.; Liu, F.; Ma, J.; Liu, M. Rational Design of Lewis Acid-Base Bifunctional Nanopolymers with High Performance on CO2/Epoxide Cycloaddition without a Cocatalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138715. [Google Scholar]

| Serial Number | Sample Name | N (%) | C (%) | H (%) | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MCA | 58.10 | 31.39 | 3.51 | 0.540 |

| 2 | MCA-SST | 59.02 | 30.06 | 3.14 | 0.509 |

| 3 | MTAB | 59.10 | 27.20 | 4.58 | 0.406 |

| Entry | Sample Name | Specific Surface AreaBET (m2 g−1) | Pore Size a (nm) | Pore Volume a (cm3 g−1) | CO2 Adsorption b (cm3 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MCA | 227.6 | 26.3 | 0.991 | 13.6 |

| 2 | MCA-SST | 248.8 | 17.4 | 0.407 | 4.4 |

| 3 | MTAB | 19.5 | 15.3 | 0.075 | 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, M.; Chen, C.; Verpoort, F. Mechanism and Performance of Melamine-Based Metal-Free Organic Polymers with Modulated Nitrogen Structures for Catalyzing CO2 Cycloaddition. Catalysts 2026, 16, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020143

Gao Y, Li S, Jiang M, Chen C, Verpoort F. Mechanism and Performance of Melamine-Based Metal-Free Organic Polymers with Modulated Nitrogen Structures for Catalyzing CO2 Cycloaddition. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020143

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yifei, Shuai Li, Min Jiang, Cheng Chen, and Francis Verpoort. 2026. "Mechanism and Performance of Melamine-Based Metal-Free Organic Polymers with Modulated Nitrogen Structures for Catalyzing CO2 Cycloaddition" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020143

APA StyleGao, Y., Li, S., Jiang, M., Chen, C., & Verpoort, F. (2026). Mechanism and Performance of Melamine-Based Metal-Free Organic Polymers with Modulated Nitrogen Structures for Catalyzing CO2 Cycloaddition. Catalysts, 16(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020143