Conventional and Intensified Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Renewable Hydrogen Production: Challenges and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

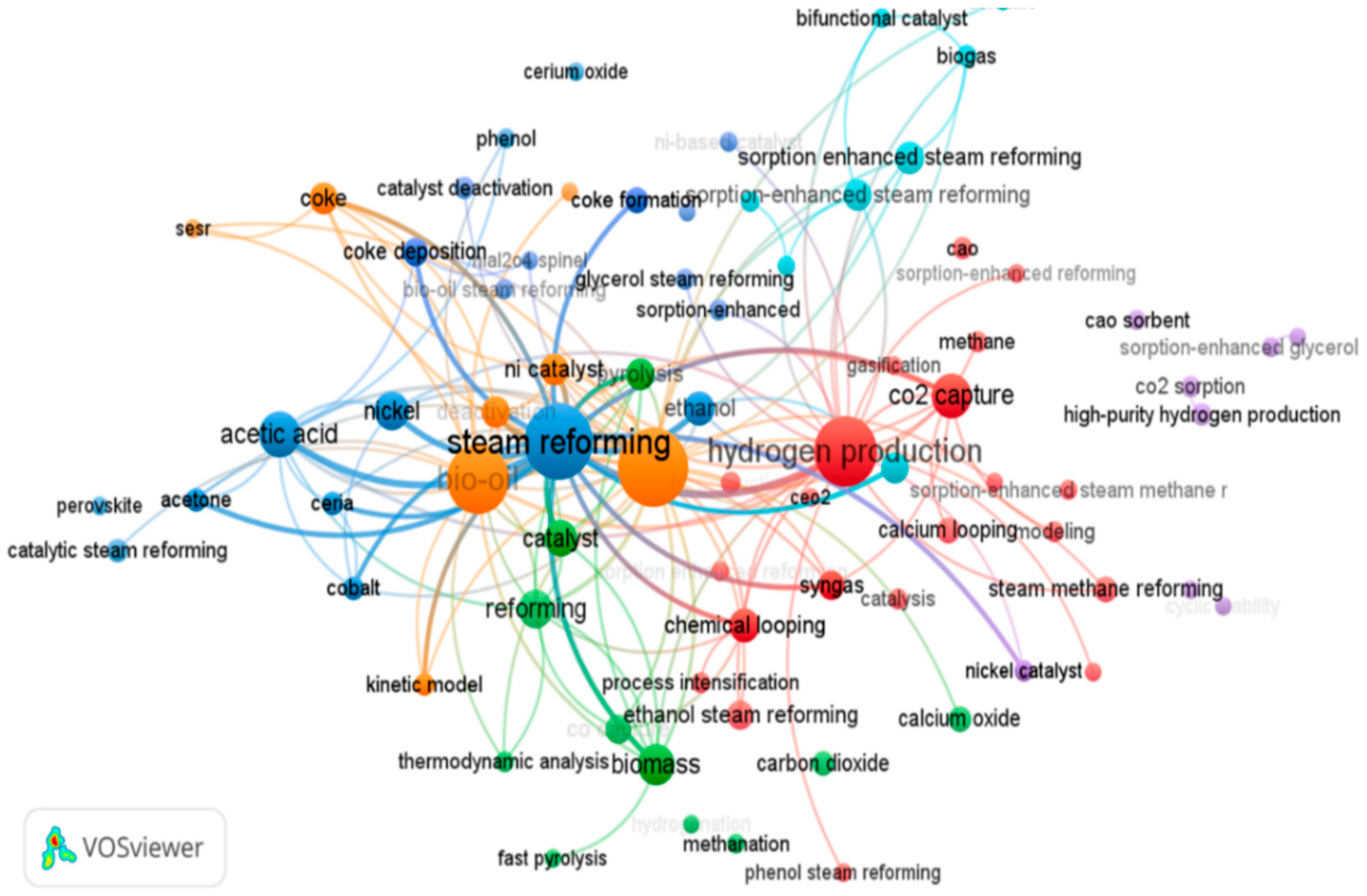

Interest of the Review Within Current Literature

2. Challenges of H2 Production from Bio-Oil

2.1. Complexity of Bio-Oil as Feedstock

2.2. Catalyst Deactivation

- (1)

- Stable equilibrium: The reaction operates under thermodynamic equilibrium. During this stage, excess catalyst compensates for initial deactivation.

- (2)

- Initial deactivation: The catalyst activity slightly declines owing to morphological changes in the catalyst due to catalyst sintering phenomena.

- (3)

- Pseudostable state: Despite some deactivation, the catalyst retains high activity.

- (4)

- Major deactivation: A sharp drop in H2 and CO2 production, with increased hydrocarbon formation. The reaction indices change rapidly but slow down as time-on-stream (TOS) increases. This stage is highly linked to excessive coke deposition over the catalytic sites.

- (5)

- Slow deactivation: The catalyst loses reforming activity but retains residual function, particularly for cracking oxygenates and facilitating the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction. This remaining activity is linked to the support interactions with catalytic active sites.

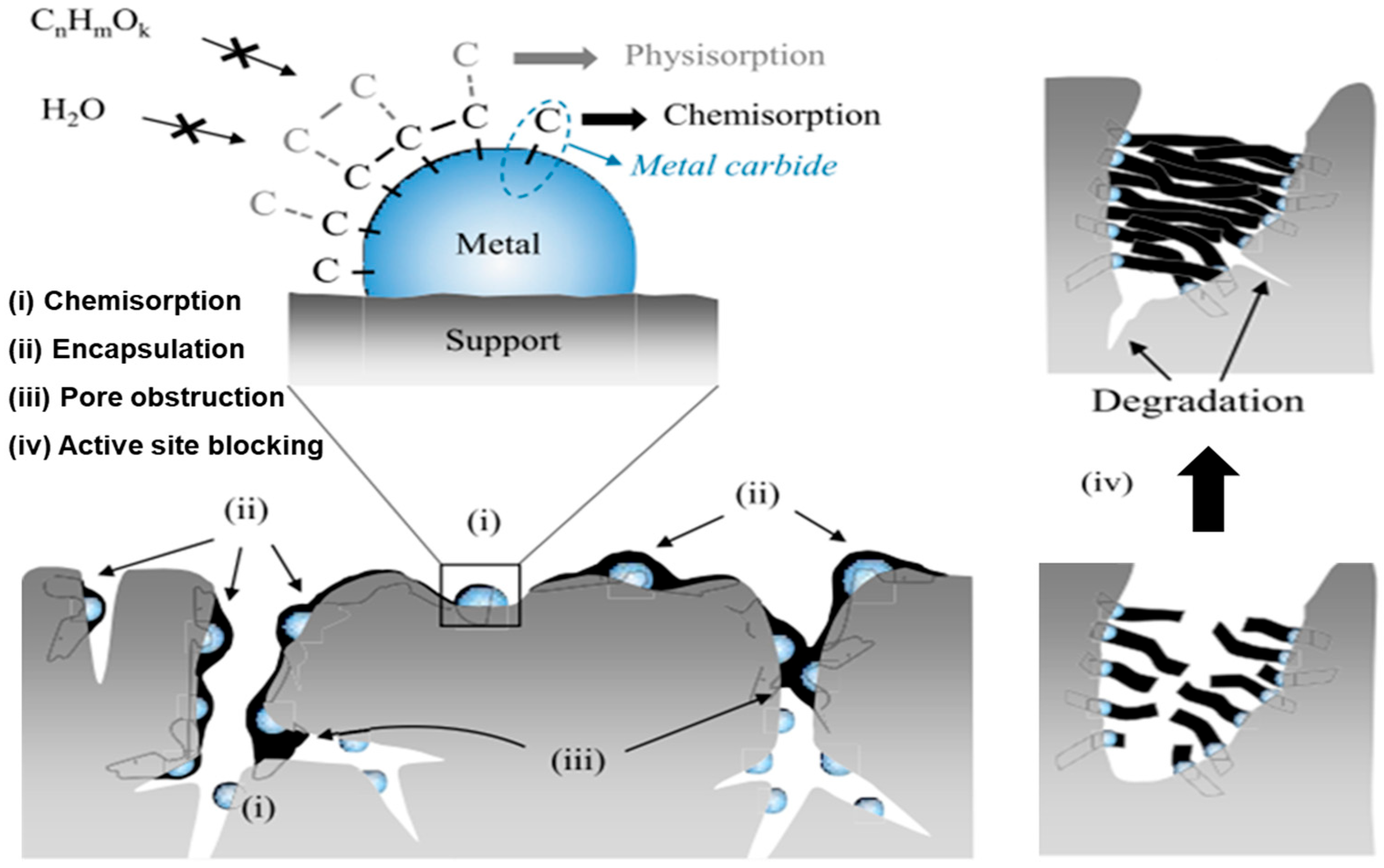

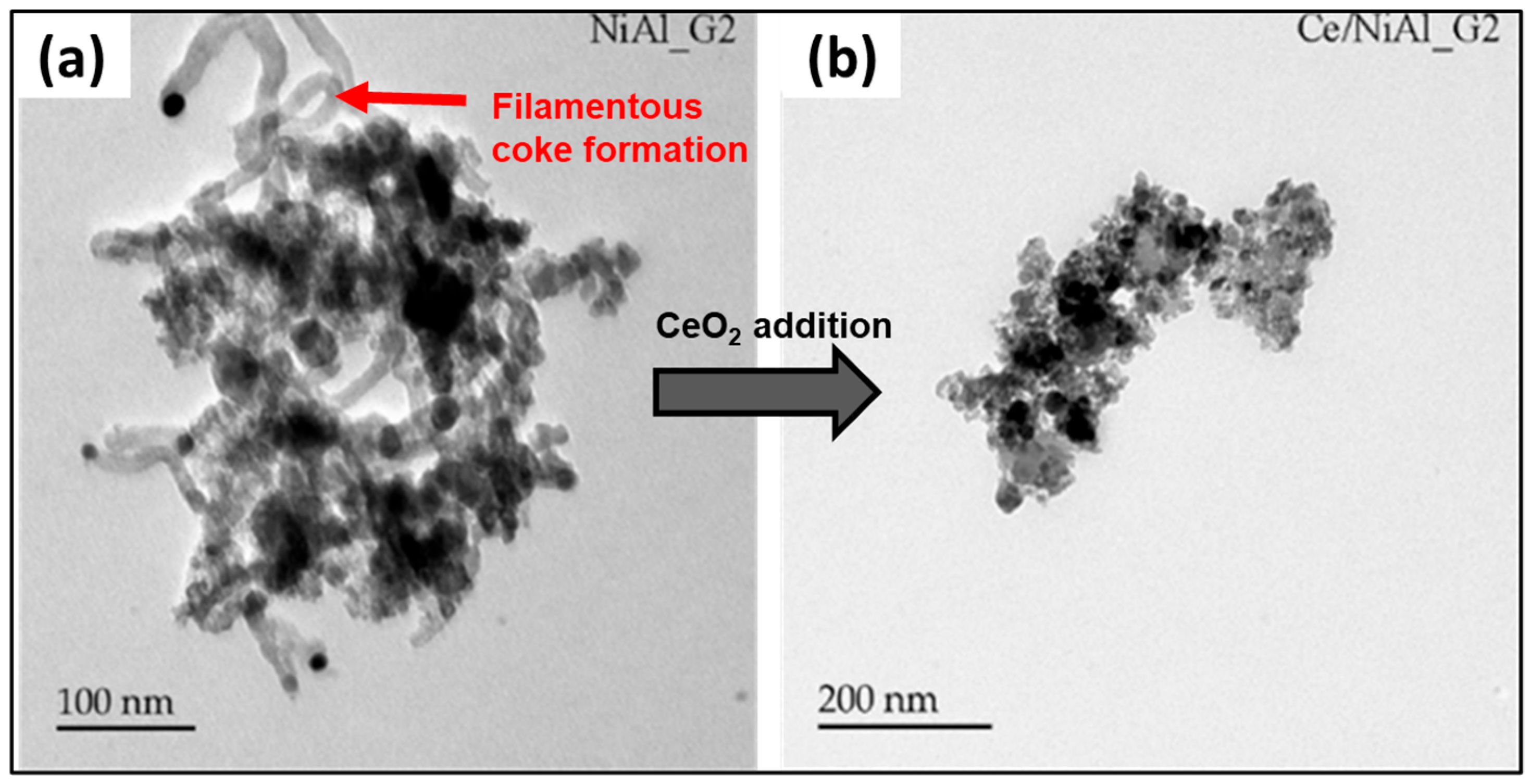

2.2.1. Coke Formation

2.2.2. Sintering of Active Sites

3. Conventional Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil

3.1. Catalyst

3.2. Catalyst Support

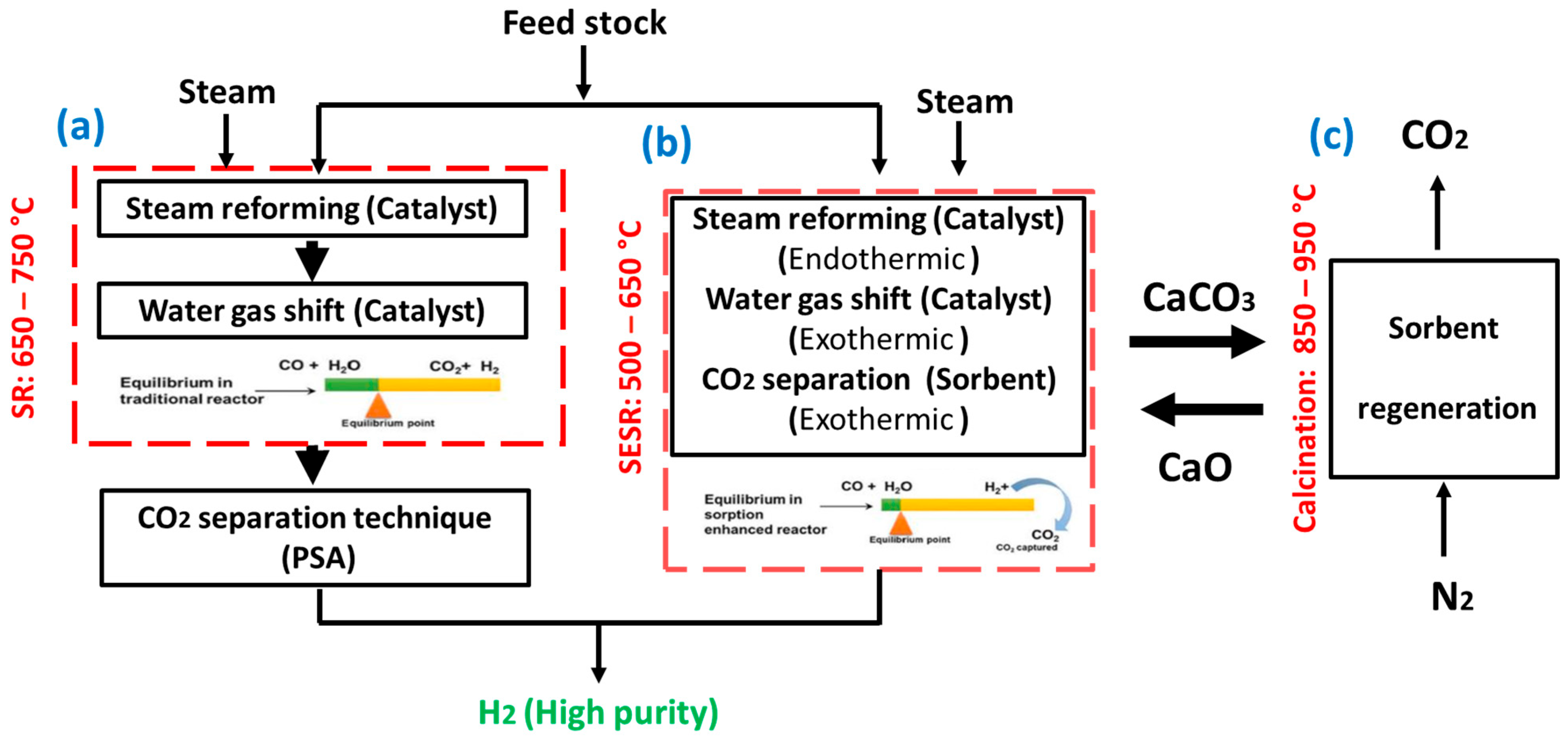

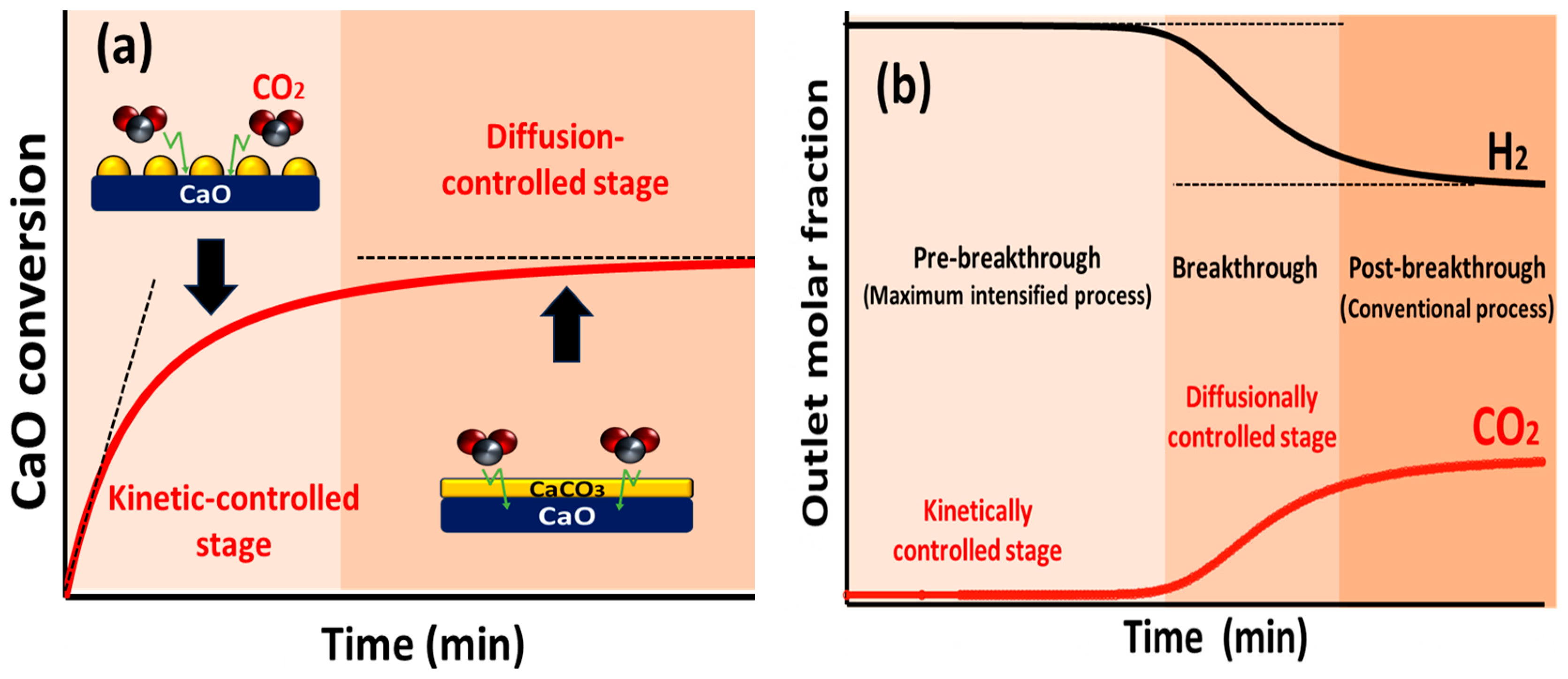

4. Intensified SESRBO for High-Purity H2 Production

4.1. Effect of Operating Parameters

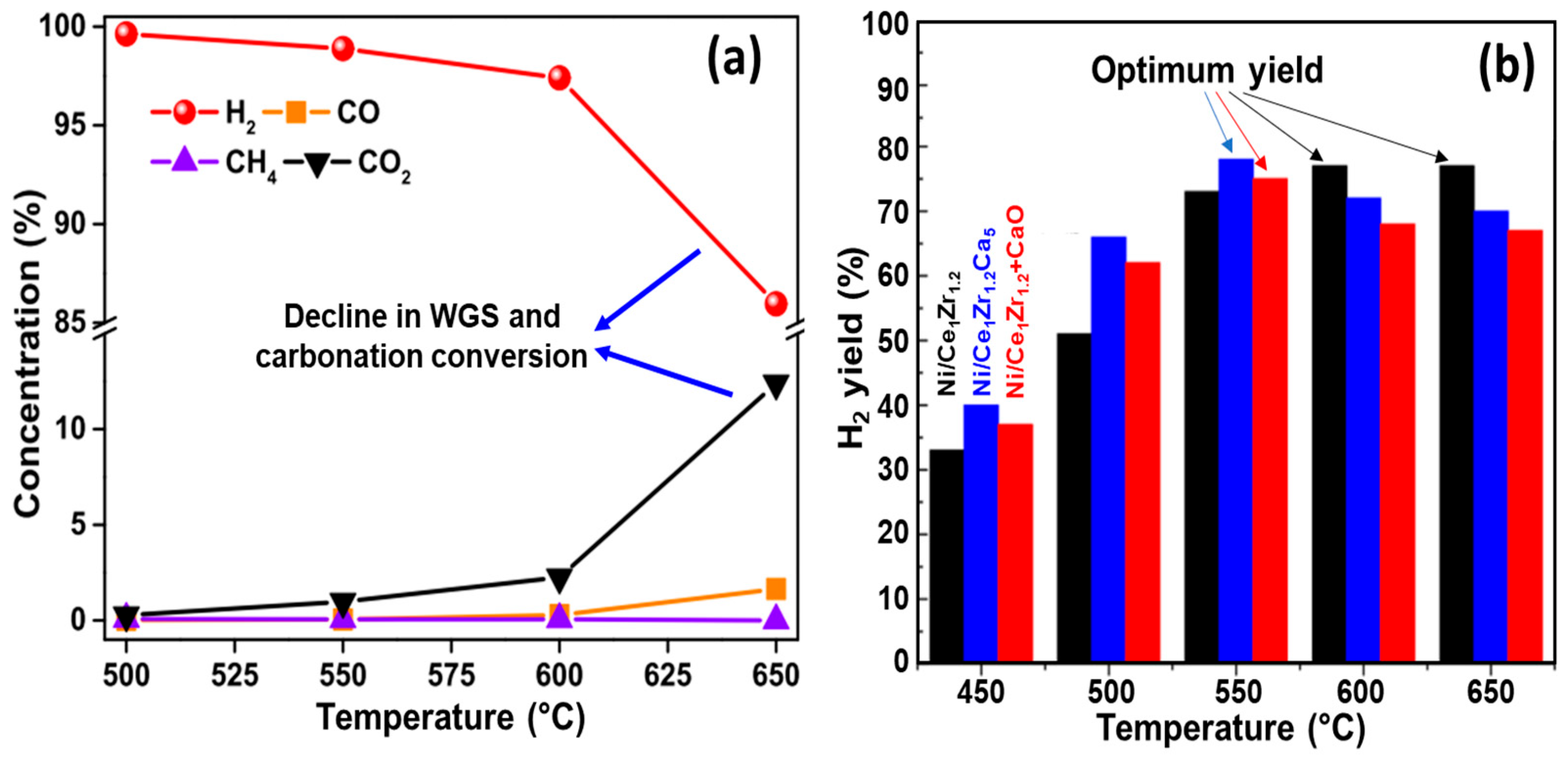

4.1.1. Effect of Temperature

4.1.2. Effect of Steam

- (i)

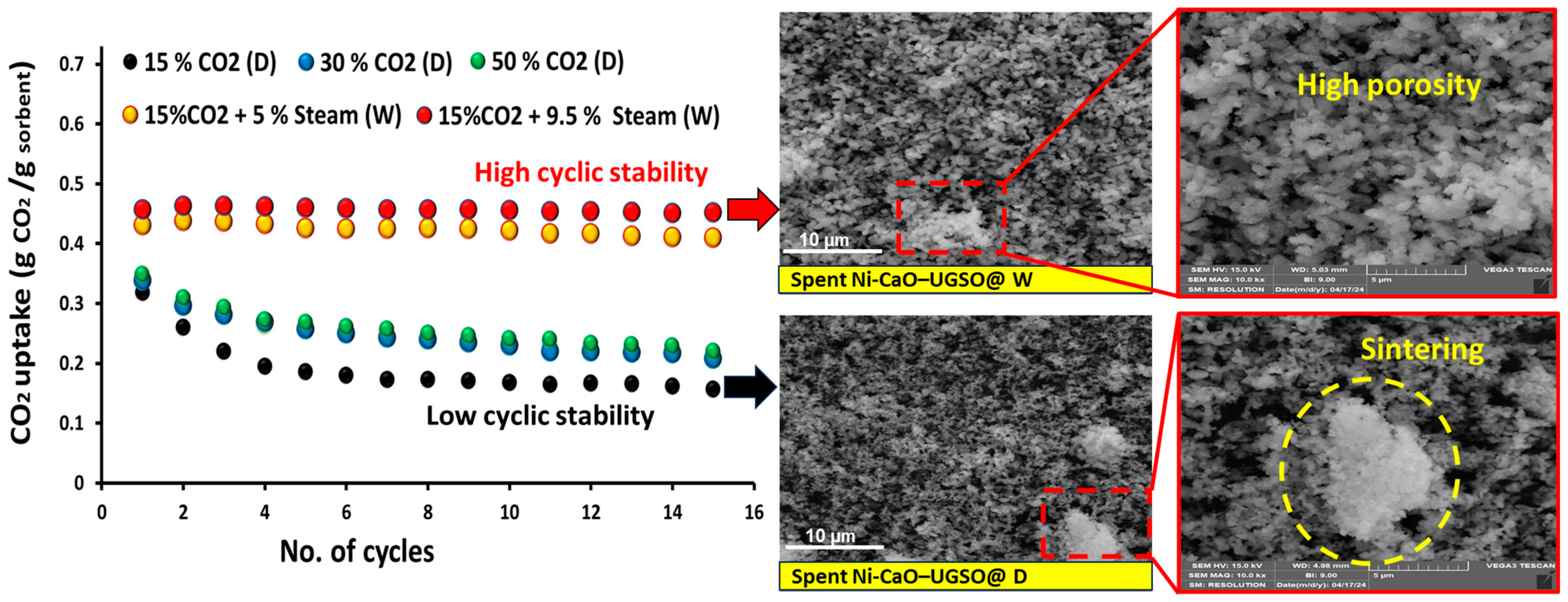

- Chemical and kinetic points of view: The enhancement of carbonation conversion in the fast reaction-controlled stage is attributed to the formation of Ca(OH)2 as a transient intermediate (Equation (11)). This hypothesis found support in experiments conducted by Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh et al. [75], who associated the accelerated carbonation rate during the initial stage with the formation of bicarbonates, which enable the sorption of two CO2 molecules per active site, thereby enhancing the CO2 capture efficiency of CaO-based sorbents (Equation (12)). Consequently, it could be concluded that the carbonation reaction in CaO-based BFMs is kinetically more favorable at wet carbonation conditions.

- (ii)

- Morphological point of view: The dynamic formation and decomposition of Ca(OH)2 leads to an increase in the surface area and an expansion in pore volume. This improvement in the textural properties under wet conditions promotes CO2 diffusion. Increasing the steam concentration during the carbonation process serves to alleviate the decline in CO2 capture capacity by developing a more stable pore structure. As a result, it supports a higher carbonation rate, particularly during the second carbonation step, which is predominantly controlled by CO2 diffusion. Wang et al. [105] proposed that OH formation is crucial for enhancing CO2 diffusion in the product layer. Therefore, the carbonation reaction is governed by the diffusion of CO32− and O2− ions between reaction interfaces.

4.1.3. Effect of Other Operating Factors

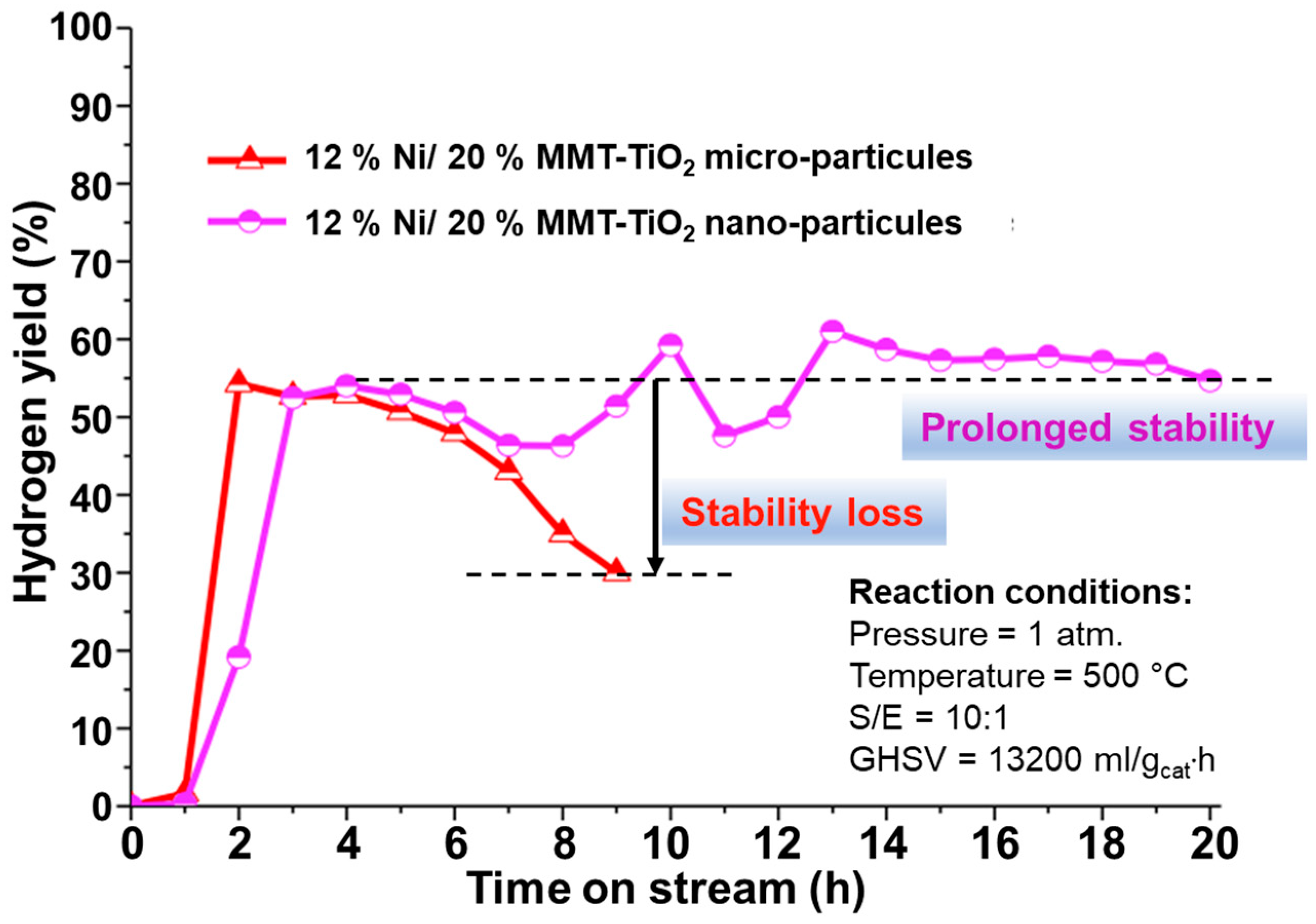

4.2. Progress in the SESRBO

4.2.1. Development and Application of Hybrid Catalyst-Sorbent Materials

Improvement of Sorption Capacity

Enhancement of Pore Structure Stability

Improvement of Coke Deposition Resistance

- (i)

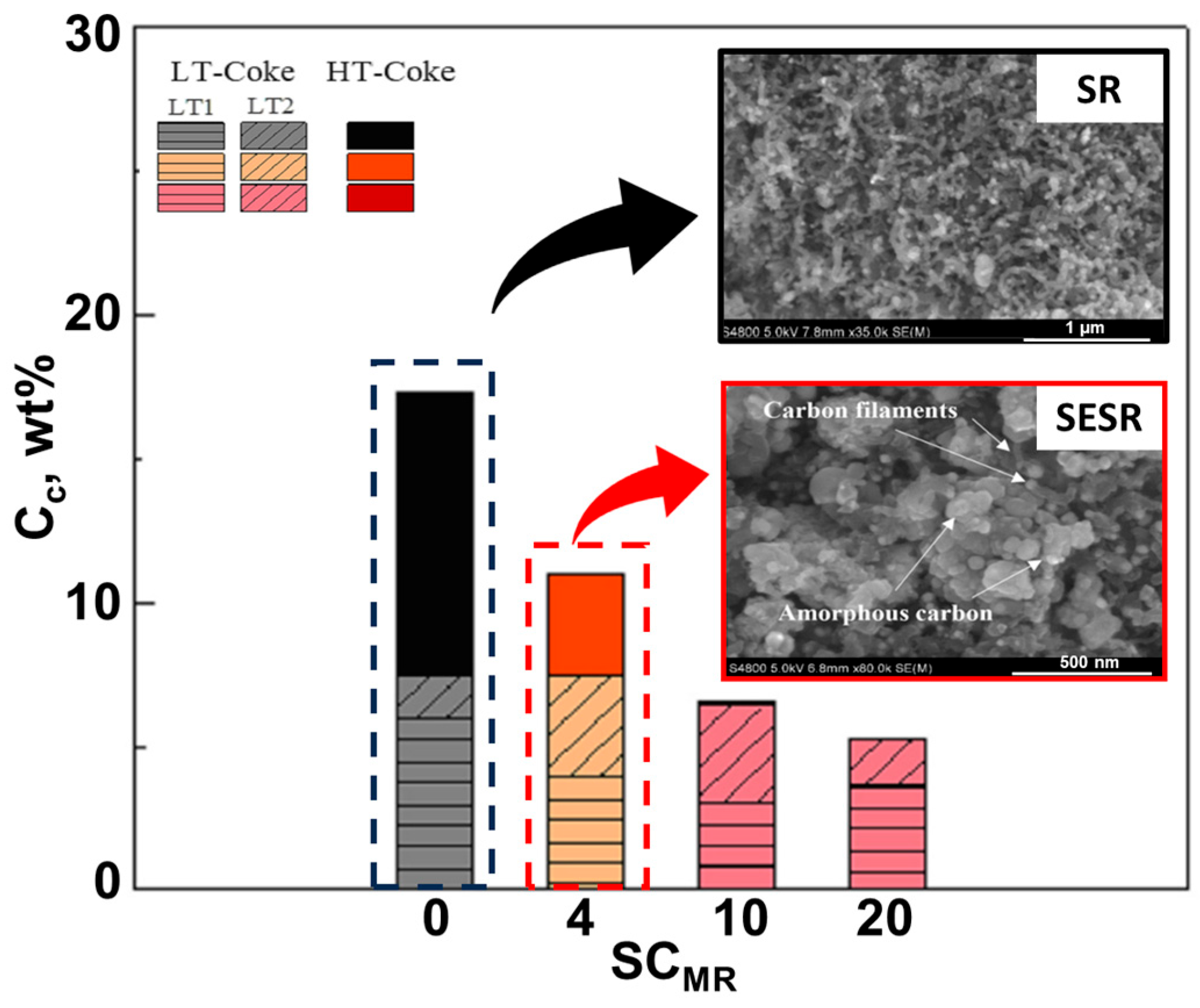

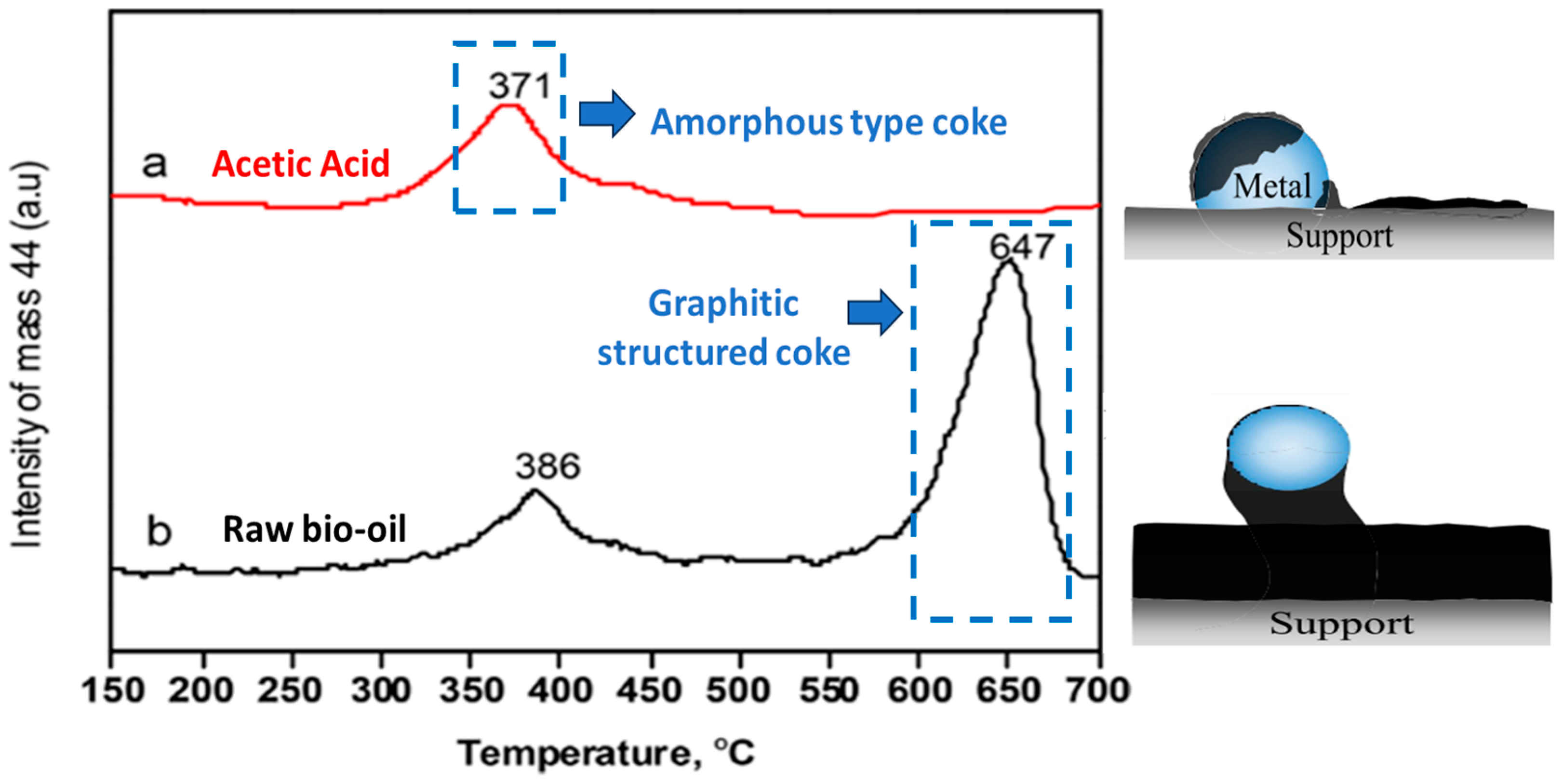

- The chemical composition of the feeding stock [31,99]. For example, Dang et al. [90] and Gao et al. [92] observed low carbon deposition during SESR of glycerol. However, for crude glycerol, the tendency of coke formation (both amorphous and graphitic) becomes much more significant due to the presence of some constituents, especially acetic and oleic acids [30]. An increased formation of coke was also noted in another study on SESR of crude glycerol, mainly due to the presence of fatty acid methyl esters [149]. According to TPO results reported by Li et al. [84] (Figure 18), the amount of coke in the case of raw bio-oil (resulting from sawdust pyrolysis) was much higher than that of acetic acid after SESR over Ni/Ce1.2Zr1Ca5 BFMs. The authors argued that the presence of high C/H compounds, such as phenols and their derivatives, in raw bio-oil accelerates coke formation, as these compounds polymerize into complex carbonaceous structures (coke precursors), leading to catalyst deactivation [150]. Similarly, Esteban-Diez et al. [94] achieved high H2 purities (99.2–99.4%) and H2 yields of 90.2–95.9% during the SESR of individual model compounds of BO (acetic acid and acetone) at 575 °C (optimized temperature) and a S/C of 3, using a mechanical mixture of Pd/Co-Ni + dolomite with an SCMR ratio of 5. However, when processing the blend of these compounds in the same conditions, H2 yield was reduced to 83.3–88.6%. This significant decline was attributed to incomplete reactant conversion caused by excessive coke deposition.

- (ii)

- Operating temperature. Valle et al. [32] emphasized that temperature has a significant influence on the nature of the coke formed. After SR of raw bio-oil (from pine sawdust) at 550 °C, amorphous carbon was detected on the spent catalyst (Ni/La2O3-αAl2O3), compared to the filamentous one at 700 °C. A similar conclusion was reached by Landa [31]. The reactor type also influences the coke deposition. Unlike fixed-bed reactors, fluidized-bed reactors are less prone to coke formation. For instance, after 30 min of time on stream (TOS) during SESRBO runs operated by [99], the coke deposited on the developed hybrid material (mechanical mixture of Ni/Al2O3 (catalyst) + dolomite (sorbent)) was reported as 3.7% and 2.9% in the fixed- and fluidized-bed reactors, respectively.

- (iii)

- BFM composition. Supporting materials and catalyst promoters play a crucial role in enhancing the removal of carbon deposits from the catalyst/BFM surface. In particular, rare-earth oxides such as CeO2, ZrO2, and La2O3 are widely recognized for their effectiveness in enhancing coke resistance in catalytic processes by facilitating redox reactions, enhancing oxygen mobility, and promoting carbon gasification. The presence of basic oxide supports like alkaline earth oxides (e.g., MgO) and transition metal oxides (e.g., Fe2O3) improves the neutral property of acidic supports, such as alumina, by mitigating coke formation on strong acidic sites [35,151].

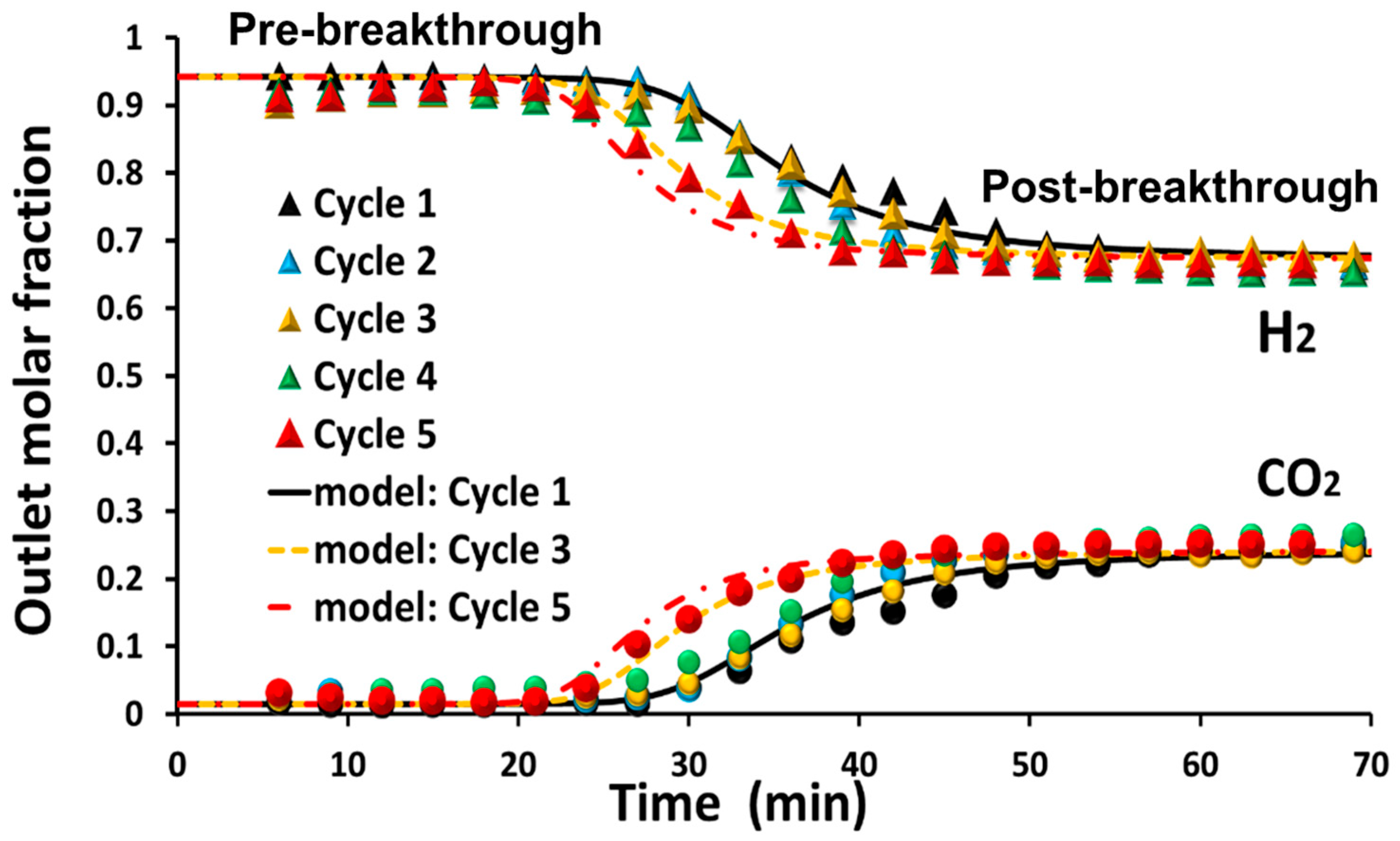

4.2.2. Process Simulation and Kinetics Insights

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- Bio-oil (derived from biomass) has a high energy density. While it represents a complex mixture of very interesting compounds, such as ethanol, acetic acid, and phenol, it also contains considerable amounts of water. Therefore, the steam reforming of bio-oil enables its direct utilization and eliminates the need for an expensive water separation step before use (an economic and practical advantage). This process displays the feasibility of reliable H2 production.

- (2)

- Due to the intrinsic complexity of bio-oil, most works considered single-model compounds to study the steam reforming of bio-oil. However, to truly understand the complexity of this process, significant research on a more realistic bio-oil composition is highly needed.

- (3)

- Combining the valorization of (i) bio-oil (liquid waste from residual biomass) as reforming feedstock and (ii) solid residues as supporting material for SRBO and/or stabilizers for SESRBO represents an effective approach for sustainable and renewable hydrogen production, maximizing the benefit of the available resources, while also reducing the environmental impact.

- (4)

- Metal sintering and coke deposition are key challenges for commonly used catalysts. Further in-depth research is still required to better understand the mechanisms underlying these phenomena.

- (5)

- Achieving high H2 purity alone is not sufficient to ensure the practicality of the intensification process in industry. Extending the pre-breakthrough period through proper system design and operation is equally vital to limit switching between reforming/carbonation and sorbent regeneration periods, thereby optimizing efficiency and economic viability.

- (6)

- In the context of the future development of SESRBO, particular attention should be paid to catalyst activity loss caused by coke deposition, which is particularly pronounced for feedstocks with a high C/H ratio, such as simulated and raw bio-oils.

- (7)

- The successful industrial implementation of SESRBO requires sustained development and optimization of cost-effective BFMs that exhibit high activity, long-term stability, and strong regenerative capacity. Integrating solid industrial waste into the formulation of BFMs can also represent a promising approach, offering strong synergy between economic benefits and environmental considerations.

- (8)

- The combination of SESRBO with other advanced technologies, such as dry reforming of methane, could offer significant potential in terms of reducing thermal energy requirements and improving overall system efficiency. In such a configuration, the CO2 captured by the sorbent during the SESR process can then be used as a reactant in dry reforming of methane, enabling the production of high-purity hydrogen.

- (9)

- Converting the in situ-captured CO2 into value-added chemicals (e.g., CO/syngas, methanol, formic acid, etc.) could enhance the process economics and establish integrated biorefinery concepts.

- (10)

- Further research is still needed to fully understand the reaction kinetics and mechanisms involved in sorption-enhanced processes, as well as to optimize the treatment of raw or aqueous bio-oil mixtures for practical applications. In this context, reactor simulation can be combined with quantum mechanical modeling, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), which provides a powerful tool for investigating reaction mechanisms with high accuracy and microscopic resolution, particularly in CO2 capture and related catalytic processes.

- (11)

- To assess the economic feasibility of the SESRBO process, a comprehensive techno-economic analysis of the integrated system would be of interest, considering factors such as high-temperature regeneration and reactor switching requirements for cyclic operation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chong, C.C.; Cheng, Y.W.; Ng, K.H.; Vo, D.V.N.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, J.W. Bio-Hydrogen Production from Steam Reforming of Liquid Biomass Wastes and Biomass-Derived Oxygenates: A Review. Fuel 2022, 311, 122623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi Soltani, S.; Lahiri, A.; Bahzad, H.; Clough, P.; Gorbounov, M.; Yan, Y. Sorption-Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming for Combined CO2 Capture and Hydrogen Production: A State-of-the-Art Review. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desgagnés, A.; Alizadeh Sahraei, O.; Iliuta, M.C. Improvement Strategies for Ni-Based Alcohol Steam Reforming Catalysts. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 86, 447–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.M.; Abbas, S.Z.; Maqbool, F.; Ramirez-Solis, S.; Dupont, V.; Mahmud, T. Modeling of Sorption Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming in an Adiabatic Packed Bed Reactor Using Various CO2 Sorbents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.B.; Zhan, G.; Sun, D.; Huang, J.; Li, Q. The Development of Bifunctional Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation to Hydrocarbonsviathe Methanol Route: From Single Component to Integrated Components. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 5197–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.; Maheria, K.C.; Kumar Dalai, A. Bio-Oil Valorization: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trane, R.; Dahl, S.; Skjøth-Rasmussen, M.S.; Jensen, A.D. Catalytic Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 6447–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiabudi, H.D.; Aziz, M.A.A.; Abdullah, S.; Teh, L.P.; Jusoh, R. Hydrogen Production from Catalytic Steam Reforming of Biomass Pyrolysis Oil or Bio-Oil Derivatives: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 18376–18397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, N.; Valecillos, J.; Remiro, A.; Valle, B.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Effect of Reaction Conditions on the Deactivation by Coke of a NiAl2O4 Spinel Derived Catalyst in the Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 297, 120445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, L.; Remiro, A.; Valecillos, J.; Valle, B.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Unveiling the Deactivation by Coke of NiAl2O4 Spinel Derived Catalysts in the Bio-Oil Steam Reforming: Role of Individual Oxygenates. Fuel 2022, 321, 124009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Xu, T.; Xiao, B.; Liu, S.; Hu, Z.; Li, J. CO2 Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Phenol Using Ni–M/CaO–Ca12Al14O33 (M = Cu, Co, and Ce) as Catalytic Sorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDowell, N.; Florin, N.; Buchard, A.; Hallett, J.; Galindo, A.; Jackson, G.; Adjiman, C.S.; Williams, C.K.; Shah, N.; Fennell, P. An Overview of CO2 Capture Technologies. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 1645–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Memon, M.Z.; Seelro, M.A.; Fu, W.; Gao, Y.; Ji, G. A Review of CO2 Sorbents for Promoting Hydrogen Production in the Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming Process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23358–23379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y. Catalysts for Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 4627–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G.; Castaño, P. Coke Formation and Deactivation during Catalytic Reforming of Biomass and Waste Pyrolysis Products: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dai, Y.; Yang, H.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A Review of Recent Advances in Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15557–15578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogo, S.; Sekine, Y. Recent Progress in Ethanol Steam Reforming Using Non-Noble Transition Metal Catalysts: A Review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 199, 106238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Zhang, S.; Sarker, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Fini, E.H. Review on Aging of Bio-Oil from Biomass Pyrolysis and Strategy to Slowing Aging. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 11665–11692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.G.; Otoikhian, K.S.; Ighalo, J.O. Steam Reforming of Biomass Pyrolysis Oil: A Review. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2019, 17, 20180328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L. Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Biomass-Based Feedstocks: Towards Sustainable Hydrogen Evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, A.; Remiro, A.; García, V.; Castaño, P.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Supported and Bulk Ni Catalysts for Hydrogen Production. Catalysts 2018, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sui, M.; Yan, Y. A Comparison of Steam Reforming of Two Model Bio-Oil Fractions. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2008, 31, 1748–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, A.; Arandia, A.; Oar-Arteta, L.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Stability of a Rh/CeO2-ZrO2 Catalyst in the Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 3588–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, A.; Remiro, A.; Valle, B.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Deactivation of Ni Spinel Derived Catalyst during the Oxidative Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil. Fuel 2020, 276, 117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; He, L. Towards an Efficient Hydrogen Production from Biomass: A Review of Processes and Materials. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 490–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A.; Valle, B.; Resasco, D.E.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G.; Castaño, P. Temperature Programmed Oxidation Coupled with In Situ Techniques Reveal the Nature and Location of Coke Deposited on a Ni/La2O3-Al2O3 Catalyst in the Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 2311–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Ruocco, C.; Cortese, M.; Martino, M. Bioalcohol Reforming: An Overview of the Recent Advances for the Enhancement of Catalyst Stability. Catalysts 2020, 10, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennard, D.; French, R.; Czernik, S.; Josephson, T.; Schmidt, L. Production of Synthesis Gas by Partial Oxidation and Steam Reforming of Biomass Pyrolysis Oils. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 4048–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, N.; Valle, B.; Valecillos, J.; Remiro, A.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Feasibility of Online Pre-Reforming Step with Dolomite for Improving Ni Spinel Catalyst Stability in the Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 215, 106769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.N.M.; Alizadeh Sahraei, O.; Olivier, A.; Iliuta, M.C. Effect of Impurities on Glycerol Steam Reforming over Ni-Promoted Metallurgical Waste Driven Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 4614–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, L.; Remiro, A.; Valecillos, J.; Valle, B.; Sun, S.; Wu, C.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming (SESR) of Raw Bio-Oil with Ni Based Catalysts: Effect of Sorbent Type, Catalyst Support and Sorbent/Catalyst Mass Ratio. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 247, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Aramburu, B.; Olazar, M.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Ni/La2O3-Al2O3: Influence of Temperature on Product Yields and Catalyst Deactivation. Fuel 2018, 216, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megía, P.J.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; Ruiz-Abad, M.; Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A. Coke Evolution in Simulated Bio-Oil Aqueous Fraction Steam Reforming Using Co/SBA-15. Catal. Today 2021, 367, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, M.; Iliuta, M.C. Embedding Ni in Ni-Al Mixed-Metal Alkoxide for the Synthesis of Efficient Coking Resistant Ni-CaO-Based Catalyst-Sorbent Bifunctional Materials for Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16746–16756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shejale, A.D.; Yadav, G.D. Sustainable and Selective Hydrogen Production by Steam Reforming of Bio-Based Ethylene Glycol: Design and Development of Ni–Cu/Mixed Metal Oxides Using M (CeO2, La2O3, ZrO2)–MgO Mixed Oxides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 4808–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioche, C.; Kulkarni, S.; Meunier, F.C.; Breen, J.P.; Burch, R. Steam Reforming of Model Compounds and Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oil on Supported Noble Metal Catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2005, 61, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, M.; Alizadeh Sahraei, O.; Aissaoui, M.; Iliuta, M.C. A Novel Synthesis of NiAl2O4 Spinel from a Ni-Al Mixed-Metal Alkoxide as a Highly Efficient Catalyst for Hydrogen Production by Glycerol Steam Reforming. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 265, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmane, V.G.; Owen, S.L.; Abrokwah, R.Y.; Kuila, D. Mesoporous Nanocrystalline TiO2 Supported Metal (Cu, Co, Ni, Pd, Zn, and Sn) Catalysts: Effect of Metal-Support Interactions on Steam Reforming of Methanol. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 408, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Kopac, J. Assessment of the Catalytic Performances of Nanocomposites Materials Based on 13X Zeolite, Calcium Oxide and Metal Zinc Particles in the Residual Biomass Pyrolysis Process. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Song, H.; Chou, L. Mesoporous Nanocrystalline Ceria-Zirconia Solid Solutions Supported Nickel Based Catalysts for CO2 Reforming of CH4. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 18001–18020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.F.; Cheng, F.F.; Hu, R.R. Hydrogen Production from Catalytic Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil Aqueous Fraction over Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 11693–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, T.; Kaul, N.; Mittal, R.; Pant, K.K. Catalytic Steam Reforming of Model Oxygenates of Bio-Oil for Hydrogen Production Over La Modified Ni/CeO2–ZrO2 Catalyst. Top. Catal. 2016, 59, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Fu, Z.Y.; Tan, H.R.; Tan, J.P.Y.; Ng, S.C.; Teo, E. Hydrothermal Synthesis of CeO2 Nanocrystals: Ostwald Ripening or Oriented Attachment? Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 3296–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Engelhard, M.; Hernandez, X.I.P.; Wang, Y. Steam Reforming of Simulated Bio-Oil on K-Ni-Cu-Mg-Ce-O/Al2O3: The Effect of K. Catal. Today 2019, 323, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bao, C.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Song, C.; Xu, Q. Thermo-Photo Synergic Effect on Methanol Steam Reforming over Mesoporous Cu/TiO2–CeO2 Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 26741–26756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natewong, P.; Prasongthum, N.; Mhadmhan, S.; Reubroycharoen, P. Fibrous Platelet Carbon Nanofibers-Silica Fiber Composite Supports for a Co-Based Catalyst in the Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2018, 560, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Tahir, M. Tri-Metallic Ni–Co Modified Reducible TiO2 Nanocomposite for Boosting H2 Production through Steam Reforming of Phenol. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8932–8949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulewa, W.; Tahir, M.; Amin, N.A.S.; Aishah, N.; Amin, S.; Amin, N.A.S. MMT-Supported Ni/TiO2 Nanocomposite for Low Temperature Ethanol Steam Reforming toward Hydrogen Production. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiro, A.; Valle, B.; Aguayo, A.T.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil in a Fluidized Bed Reactor with Prior Separation of Pyrolytic Lignin. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 7549–7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Grasham, O.; Mahmud, T.; Dupont, V. Advanced Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil with Carbon Capture: A Techno-Economic and CO2 Emissions Analysis. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Cai, Q.; Zhu, L.; Luo, Z. Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid over Coal Ash Supported Fe and Ni Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11406–11413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.F.; Wu, Y.J.; Li, P.; Yu, J.G.; Rodrigues, A.E. Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Ethanol on a Novel K-Ni-Cu-Hydrotalcite Hybrid Material. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 3842–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lu, G. Comparative Study of Alumina-Supported Transition Metal Catalysts for Hydrogen Generation by Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 99, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Galdámez, J.; García, L.; Bilbao, R. Hydrogen Production by Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil Using Coprecipitated Ni-Al Catalysts. Acetic Acid as a Model Compound. Energy Fuels 2005, 19, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabgan, W.; Abdullah, T.A.T.; Mat, R.; Nabgan, B.; Jalil, A.A.; Firmansyah, L.; Triwahyono, S. Production of Hydrogen via Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid over Ni and Co Supported on La2O3 Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 8975–8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Fu, P.; Sun, F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, A.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q. Catalytic Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil-Derived Acetic Acid over CeO2-ZnO Supported Ni Nanoparticle Catalysts. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19727–19736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riani, P.; Garbarino, G.; Canepa, F.; Busca, G. Cobalt Nanoparticles Mechanically Deposited on α-Al2O3: A Competitive Catalyst for the Production of Hydrogen through Ethanol Steam Reforming. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.A.S.; Faustino, P.B.; Assaf, J.M.; Jaroniec, M. One-Pot Synthesis of Mesoporous Ni-Ti-Al Ternary Oxides: Highly Active and Selective Catalysts for Steam Reforming of Ethanol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 6079–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.; Celik, G.; Gunduz, S.; Dogu, D.; Zhang, S.; Shan, J.; Tao, F.F.; Ozkan, U.S. Oxygen Mobility in Pre-Reduced Nano- and Macro-Ceria with Co Loading: An AP-XPS, In-Situ DRIFTS and TPR Study. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 2863–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, J.A.; Tonetto, G.M.; Pedernera, M.N.; López, E. Ni/CeO2–MgO Catalysts Supported on Stainless Steel Plates for Ethanol Steam Reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9482–9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yu, Q.; Yao, X.; Duan, W.; Zuo, Z.; Qin, Q. Hydrogen Production via Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil Model Compounds over Supported Nickel Catalysts. J. Energy Chem. 2015, 24, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, P.; Chen, G.; Li, X. Production of Hydrogen by Steam Reforming of Phenol over Ni/Al2O3-Ash Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 13592–13603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermoso, J.; He, L.; Chen, D. Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming (SESR): A Direct Route towards Efficient Hydrogen Production from Biomass-Derived Compounds. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 87, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, G.; Wang, C.; Valsamakis, I.; Chitsazan, S.; Riani, P.; Finocchio, E.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M.; Busca, G. A Study of Ni/Al2O3 and Ni–La/Al2O3 Catalysts for the Steam Reforming of Ethanol and Phenol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 174–175, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calles, J.A.; Carrero, A.; Vizcaíno, A.J.; García-Moreno, L.; Megía, P.J. Steam Reforming of Model Bio-Oil Aqueous Fraction Using Ni-(Cu, Co, Cr)/SBA-15 Catalysts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquevich, M.; Czernik, S.; Chornet, E.; Montané, D. Hydrogen from Biomass: Steam Reforming of Model Compounds of Fast-Pyrolysis Oil. Energy Fuels 1999, 13, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Remiro, A.; Aguayo, A.T.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Catalysts of Ni/α-Al2O3 and Ni/La2O3-Al2O3 for Hydrogen Production by Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil Aqueous Fraction with Pyrolytic Lignin Retention. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Xu, S.; Zhou, C. Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil from Coconut Shell Pyrolysis over Fe/Olivine Catalyst. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 141, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.B.; Gong, L.; Liu, L.; Hong, C.G.; Yuan, L.X.; Li, Q.X. Hydrogen Production by Low-Temperature Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil over Ni/HZSM-5 Catalyst. Chin. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 24, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.; Blanchard, J.; Chamoumi, M.; Abatzoglou, N. Bio-Oil Steam Reforming over a Mining Residue Functionalized with Ni as Catalyst: Ni-UGSO. Catalysts 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basagiannis, A.C.; Verykios, X.E. Catalytic Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid for Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 3343–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Suárez, E.; Guerrero-Ruiz, A.; Fernández-García, M.; Rodríguez-Ramos, I.; Kubacka, A. Efficient and Stable Ni-Ce Glycerol Reforming Catalysts: Chemical Imaging Using X-Ray Electron and Scanning Transmission Microscopy. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 165, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Cai, Q.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Z. Catalytic Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil Model Compounds for Hydrogen Production over Coal Ash Supported Ni Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 2018–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, B.; Dupont, V.; Rickett, G.; Blakeman, N.; Williams, P.T.; Chen, H.; Ding, Y.; Ghadiri, M. Hydrogen Production by Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3540–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, M.; Radfarnia, H.R.; Iliuta, M.C. Sustainable Production of High-Purity Hydrogen by Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol over CeO2-Promoted Ca9Al6O18-CaO/NiO Bifunctional Material. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9774–9786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Li, P.; Yu, J.G.; Cunha, A.F.; Rodrigues, A.E. High-Purity Hydrogen Production by Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Ethanol: A Cyclic Operation Simulation Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 8515–8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, M.; Radfarnia, H.R.; Iliuta, M.C. High Temperature CO2 Sorbents and Their Application for Hydrogen Production by Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming Process. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Bacariza, C.; Correia, P.; Pinheiro, C.I.C.; Cabrita, I. Hydrogen Production with In Situ CO2 Capture at High and Medium Temperatures Using Solid Sorbents. Energies 2022, 15, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wu, C.; Shen, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J. Progress in the Development and Application of CaO-Based Adsorbents for CO2 Capture—A Review. Mater. Today Sustain. 2018, 1–2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuliano, A.; Gallucci, K.; Foscolo, P.U. Determination of Kinetic and Diffusion Parameters Needed to Predict the Behavior of CaO-Based CO2 Sorbent and Sorbent-Catalyst Materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 6840–6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopacka-Łyskawa, D.; Czaplicka, N.; Szefer, A. CaO-Based High Temperature CO2 Sorbents—Literature Review. Chem. Process Eng.—Inz. Chem. I Proces. 2021, 42, 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Xue, Y.P.; Yan, C.F.; Wang, Z.D.; Guo, C.Q.; Huang, S.L. Sorbent Assisted Catalyst of Ni-CaO-La2O3 for Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil with Acetic Acid as the Model Compound. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2017, 119, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoniyi, O.A.; Dupont, V. Optimised Cycling Stability of Sorption Enhanced Chemical Looping Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid in a Packed Bed Reactor. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 242, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xue, H.; Hu, R. Effect of Ce/Ca Ratio in Ni/CeO2-ZrO2-CaO Catalysts on High-Purity Hydrogen Production by Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid and Bio-Oil. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Li, D.; Xue, H.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z. Hydrogen Production by Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Acetic Acid over Ni/CexZr1−xO2-CaO Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 7786–7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hong, D.; Wang, N.; Guo, X. High Purity H2 Production from Sorption Enhanced Bio-Ethanol Reforming via Sol-Gel-Derived Ni–CaO–Al2O3 Bi-Functional Materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 34449–34460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmas, T.; Jamrunroj, P.; Wongsakulphasatch, S.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Laosiripojana, N.; Gong, J.; Assabumrungrat, S. Influence of CaO Precursor on CO2 Capture Performance and Sorption-Enhanced Steam Ethanol Reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 20649–20662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, S.; Dogu, T. Sorption-Enhanced Reforming of Ethanol over Ni- and Co-Incorporated MCM-41 Type Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 8796–8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Wu, S.; Yang, G.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Peng, F.; Wang, S.; Yu, H. Hydrogen Production from Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Phenol over a Ni-Ca-Al-O Bifunctional Catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7111–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, H.; Peng, F. Co-Cu-CaO Catalysts for High-Purity Hydrogen from Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 533, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Dou, B.; Jiang, B.; Song, Y.; Du, B.; Zhang, C.; Wang, K.; Chen, H.; Xu, Y. Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol on Ni-Based Multifunctional Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 7037–7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, M.; Duchesne, J.; Iliuta, M.C. Valorization of Coal Fly Ash as a Stabilizer for the Development of Ni/CaO-Based Bifunctional Material. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3885–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissaoui, M.; Alizadeh Sahraei, O.; Shokrollahi Yancheshmeh, M.; Iliuta, M.C. Development of a Fe/Mg-Bearing Metallurgical Waste Stabilized-CaO/NiO Hybrid Sorbent-Catalyst for High Purity H2 Production through Sorption-Enhanced Glycerol Steam Reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 18452–18465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-díez, G.; Gil, M.V.; Pevida, C.; Chen, D.; Rubiera, F. Effect of Operating Conditions on the Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Blends of Acetic Acid and Acetone as Bio-Oil Model Compounds. Appl. Energy 2016, 177, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acha, E.; Chen, D.; Cambra, J.F. Comparison of Novel Olivine Supported Catalysts for High Purity Hydrogen Production by CO2 sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 42, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yu, Q.; Wei, M.; Duan, W.; Yao, X.; Zuo, Z. Hydrogen Production from Steam Reforming of Simulated Bio-Oil over Ce-Ni/Co Catalyst with in Continuous CO2 Capture. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, E.; Desgagnés, A.; Iliuta, M.C. Towards Renewable High-Purity H2 Production via Intensified Bio-Oil Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming over Wastes-Driven-Stabilized Ni/CaO Bifunctional Materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 91, 1330–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, E.; Iliuta, M.C. CeO2-ZrO2 Nanocomposite-Stabilized Ni/CaO Bifunctional Material: Novel Candidate for Sustainable Hydrogen Production via SESR of Bio-Oil. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif 2025, 218, 110531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, L.; Valecillos, J.; Remiro, A.; Valle, B.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Comparison of the NiAl2O4 Derived Catalyst Deactivation in the Steam Reforming and Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil in Packed and Fluidized-Bed Reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yu, Q.; Zuo, Z.; Han, Z.; Yao, X.; Qin, Q. Hydrogen production via sorption-enhanced catalytic steam reforming of bio-oil. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 2345–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Duan, L.; Sun, Z. Review on the Development of Sorbents for Calcium Looping. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7806–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Fang, X. Sol-gel-derived, CaZrO3-stabilized Ni/CaO-CaZrO3 bifunctional Catalyst for Sorption-Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming. Applied Catal. B Environ. 2016, 196, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J.; Jia, L.; Yu, Z.; Li, R. Optimization of Two Bio-Oil Steam Reforming Processes for Hydrogen Production Based on Thermodynamic Analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9853–9863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindén, I.; Backman, P.; Brink, A.; Hupa, M. Influence of Water Vapor on Carbonation of CaO in the Temperature Range 400–550 °C. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 14115–14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Cai, N. Multiscale Model for Steam Enhancement Effect on the Carbonation of CaO Particle. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcenegui Troya, J.J.; Moreno, V.; Sanchez-Jiménez, P.E.; Perejón, A.; Valverde, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A. Effect of Steam Injection during Carbonation on the Multicyclic Performance of Limestone (CaCO3) under Different Calcium Looping Conditions: A Comparative Study. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, R.; Li, N.; Liu, Q.Q.; Chen, S.; Liu, Q.Q.; Zhou, X. Effect of Steam on Carbonation of CaO in Ca-Looping. Molecules 2023, 28, 4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Aramburu, B.; Benito, P.L.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Biomass to Hydrogen-Rich Gas via Steam Reforming of Raw Bio-Oil over Ni/La2O3-Al2O3 Catalyst: Effect of Space-Time and Steam-to-Carbon Ratio. Fuel 2018, 216, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghungrud, S.A.; Vaidya, P.D. Improved Hydrogen Production from Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Ethanol (SESRE) Using Multifunctional Materials of Cobalt Catalyst and Mg-, Ce-, and Zr-Modified CaO Sorbents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Feng, T.; Mu, M. Sorption-Enhanced Reaction Process Using Advanced Ca-Based Sorbents for Low-Carbon Hydrogen Production. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 155, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi, C.; Cortese, M.; Greco, G.; Renda, S.; González, B.; Palma, V.; Manyà, J.J. Optimization of the Operating Conditions for Steam Reforming of Slow Pyrolysis Oil over an Activated Biochar-Supported Ni–Co Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 26915–26929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaban, A.; Narcida, M.; Harrison, D.P. Characteristics of the Reversible Reaction between CO2(g) and Calcined Dolomite. Chem. Eng. Commun. 1996, 146, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasa, G.S.; Abanades, J.C. CO2 Capture Capacity of CaO in Long Series of Carbonation/Calcination Cycles. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 8846–8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Shen, B.; Parlett, C.M.A.; Adwek, G.O.; John Anthony, E.; Williams, P.T.; Wu, C. Fundamental Studies of Carbon Capture Using CaO-Based Materials. J. Mater. Chem. 2019, 7, 9977–9987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Wang, Y.; Xing, S.; Pang, C.; Hao, Y.; Song, C.; Liu, Q. Progress in Reducing Calcination Reaction Temperature of Calcium-Looping CO2 Capture Technology: A Critical Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 137952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrión, B.; Perejón, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, P.E.; Amghar, N.; Chacartegui, R.; Manuel Valverde, J.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A. Calcination under Low CO2 Pressure Enhances the Calcium Looping Performance of Limestone for Thermochemical Energy Storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 127922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Long, J.; Li, H.; Cai, W.; Yu, H. Pd-Promoted Ni-Ca-Al Bi-Functional Catalyst for Integrated Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol and Methane Reforming of Carbonate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 230, 116226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmas, T.; Wongsakulphasatch, S.; Kui Cheng, C.; Assabumrungrat, S. Bi-Metallic CuO-NiO Based Multifunctional Material for Hydrogen Production from Sorption-Enhanced Chemical Looping Autothermal Reforming of Ethanol. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 398, 125543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Q. Carbon Dioxide Captured from Flue Gas by Modified Ca-Based Sorbents in Fixed-Bed Reactor at High Temperature. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 21, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Cai, N. Rate Equation Theory for the Carbonation Reaction of CaO with CO2. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 4607–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yin, J.; Qin, C.; Feng, B. Manufacture of Calcium-Based Sorbents for High Temperature Cyclic CO2 Capture via a Sol-Gel Process. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 12, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaudeen, S.A.; Acharya, B.; Dutta, A. CaO-Based CO2 Sorbents: A Review on Screening, Enhancement, Cyclic Stability, Regeneration and Kinetics Modelling. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 23, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, N.; Wang, Q.; Fang, M.; Cheng, L.; Luo, Z.; Cen, K. Steam Hydration Reactivation of CaO-Based Sorbent in Cyclic Carbonation/Calcination for CO2 Capture. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 5332–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgsornpeak, A.; Witoon, T.; Mungcharoen, T.; Limtrakul, J. Development of Synthetic CaO Sorbents via CTAB-Assisted Sol-Gel Method for CO2 Capture at High Temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 237, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Li, Z.; Long, J.; Yang, W.; Cai, W. Sorption-Enhanced Glycerol Steam Reforming over Hierarchical Hollow Ni-CaO-Ca12Al14O33 Bi-Functional Catalyst Derived from Hydrotalcite-like Compounds. Fuel 2022, 324, 124468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, A.; Desgagnés, A.; Iliuta, M.C. Development of a Bifunctional Material Incorporating Carbon Microspheres for the Intensified Hydrogen Production by Sorption-Enhanced Glycerol Steam Reforming. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2024, 200, 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfarnia, H.R.; Iliuta, M.C. Limestone Acidification Using Citric Acid Coupled with Two-Step Calcination for Improving the CO2 Sorbent Activity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 7002–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, S.; Zhao, Z.J.; Tian, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, H.; Assabumrungrat, S.; Muhammad, T.; Zeng, L.; Gong, J. Promotional Role of MgO on Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Ethanol over Ni/CaO Catalysts. AIChE J. 2020, 66, e16877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Ruocco, C.; Meloni, E.; Gallucci, F.; Ricca, A. Enhancing Pt-Ni/CeO2 Performances for Ethanol Reforming by Catalyst Supporting on High Surface Silica. Catal. Today 2018, 307, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutlulu, A.; Naeem, M.A.; Liu, H.J.; Kim, S.M.; Kierzkowska, A.; Fedorov, A.; Müller, C.R. Multishelled CaO Microspheres Stabilized by Atomic Layer Deposition of Al2O3 for Enhanced CO2 Capture Performance. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi, S.M.; Mohamedali, M.; Sedghkerdar, M.H.; Mahinpey, N. Stability of CaO-Based Sorbents under Realistic Calcination Conditions: Effect of Metal Oxide Supports. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 9760–9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanzadeh, L.; Taghizadeh, M. Sorption-Enhanced Ethanol Steam Reforming on Ce-Ni/MCM-41 with Simultaneous CO2 Adsorption over Na- and Zr- Promoted CaO Based Sorbent. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 21238–21250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Abdala, P.M.; Hosseini, D.; Armutlulu, A.; Margossian, T.; Copéret, C.; Müller, C. Bi-Functional Ru/Ca3Al2O6-CaO Catalyst-CO2 Sorbent for the Production of High Purity Hydrogen: Via Sorption-Enhanced Steam Methane Reforming. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 5745–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakharukova, V.P.; Potemkin, D.I.; Rogozhnikov, V.N.; Stonkus, O.A.; Gorlova, A.M.; Nikitina, N.A.; Suprun, E.A.; Brayko, A.S.; Rogov, V.A.; Snytnikov, P.V. Effect of Ce/Zr Composition on Structure and Properties of Ce1−xZrxO2 Oxides and Related Ni/Ce1−xZrxO2 Catalysts for CO2 Methanation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landa, L.; Remiro, A.; Valecillos, J.; Valle, B.; Bilbao, J.; Gayubo, A.G. Performance of NiAl2O4 Spinel Derived Catalyst + Dolomite in the Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming (SESR) of Raw Bio-Oil in Cyclic Operation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 58, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, M.; Nagai, T.; Matsushita, J. Development of Porous Solid Reactant for Thermal-Energy Storage and Temperature Upgrade Using Carbonation/Decarbonation Reaction. Appl. Energy 2001, 69, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.C.; Chang, P.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Peng, C.H. Multi-Metals CaMgAl Metal-Organic Framework as CaO-Based Sorbent to Achieve Highly CO2 Capture Capacity and Cyclic Performance. Materials 2020, 13, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, F.; Yang, Y. A Bi-Functional Co-CaO-Ca12Al14O33 Catalyst for Sorption-Enhanced Steam Reforming of Glycerol to High-Purity Hydrogen. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 286, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, B.; Luo, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Ethanol over Ni-Based Catalyst Coupling with High-Performance CaO Pellets. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Liang, S.; Yang, W.; Cai, W. High-Purity Hydrogen Production from Phenol on Ni-CaO-Ca12Al14O33 Multifunctional Catalyst Derived from Recovered Layered Double Hydroxide. Fuel 2023, 332, 126041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh Sahraei, O.; Gao, K.; Iliuta, M.C. Application of industrial solid wastes in catalyst and chemical sorbent development for hydrogen/syngas production by conventional and intensified steam reforming. In New Dimensions in Production and Utilization of Hydrogen; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Chapter 2; pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesha, M.; Khoja, A.H.; Butt, F.A.; Sikandar, U.; Javed, A.H.; Naqvi, S.R.; Din, I.U.; Mehran, M.T. Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Methane over Waste-Derived CaO Promoted MgNiAl Hydrotalcite Catalyst for Sustainable H2 production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, C.; Ren, Q. Feasibility of CO2/SO2 Uptake Enhancement of Calcined Limestone Modified with Rice Husk Ash during Pressurized Carbonation. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 93, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Ren, Q.; Duan, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, X. Effect of Rice Husk Ash Addition on CO2 Capture Behavior of Calcium-Based Sorbent during Calcium Looping Cycle. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Khalili, N. Fly-Ash-Modified Calcium-Based Sorbents Tailored to CO2 Capture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 1888–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; He, Z.; Wang, Z. Fabrication and CO2 Capture Performance of Magnesia-Stabilized Carbide Slag by by-Product of Biodiesel during Calcium Looping Process. Appl. Energy 2016, 168, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Jiang, J.; Li, K.; Tian, S.; Liu, Z.; Shi, J.; Chen, X.; Fei, J.; Lu, Y. Cyclic Performance of Waste-Derived SiO2 Stabilized, CaO-Based Sorbents for Fast CO2 Capture. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 7004–7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliuta, M.C. Intensified Processes for CO2 Capture and Valorization by Catalytic Conversion. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2024, 205, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermoso, J.; He, L.; Chen, D. Production of High Purity Hydrogen by Sorption Enhanced Steam Reforming of Crude Glycerol. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14047–14054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafili, A.; Charisiou, N.D.; Douvartzides, S.L.; Siakavelas, G.I.; Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Papadakis, V.G.; Goula, M.A. Recent Progress in the Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Hydrogen Production: A Review of Operating Parameters, Catalytic Systems and Technological Innovations. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, V.; Ruocco, C.; Castaldo, F.; Ricca, A.; Boettge, D. Ethanol Steam Reforming over Bimetallic Coated Ceramic Foams: Effect of Reactor Configuration and Catalytic Support. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 12650–12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliuta, I.; Desgagnés, A.; Aulestia, A.Y.; Pfeiffer, H.; Iliuta, M.C. Intensified Bio-Oil Steam Reforming for High-Purity Hydrogen Production: Numerical Simulation and Sorption Kinetics. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 48, 8783–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, E.; Iliuta, I.; Desgagnés, A.; Poulin, C.; Iliuta, M.C. Intensified Simulated Bio-Oil Steam Reforming for Renewable Hydrogen Production over CeO2-Promoted Ni/CaO Bifunctional Material: Experimental Kinetics and Reactor Modeling. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 124932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Properties |

|---|---|

| Viscosity | A dense complex mixture of oxygenated organic compounds, consequently, it becomes difficult to pump (operational challenge). |

| pH | Acidic nature, with a pH commonly between 2 and 4. The acidity of bio-oil can cause corrosion and stability issues. |

| Heating value | Relatively low, typically lower than traditional fossil fuels such as gasoline and diesel. |

| Stability | Highly unstable and incompatible with conventional liquid fuels, primarily due to its high-water content. Over time, bio-oil degrades, resulting in the formation of sludge and solid residues. This degradation can be further accelerated by factors such as elevated temperatures, exposure to oxygen, and UV light. |

| Composition | The composition of bio-oil varies depending mainly on the applied feedstock and the pyrolysis conditions. It also may contain some impurities, especially sulfur, which can deactivate the catalyst. |

| Process | Reaction | (kJ/mol) | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SR of oxygenates | >0 | (1) | |

| Water gas shift (WGS) | −41.2 | (2) | |

| Overall reaction (SR (1) + WGS (2)) | >0 | (3) | |

| SR of methane | 206 | (4) | |

| Boudouard reaction | 172.4 | (5) | |

| Cracking of oxygenates | >0 | (6) | |

| Methane decomposition | 74.9 | (7) | |

| Coke gasification | 131.3 | (8) |

| Feedstock | Operating Conditions | Reactor | Catalyst | Catalytic Activity | Ref. & Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | S/C | Feeding Rate | Type | Prep. Method | Conv. (%) | YH2 (%) | |||

| Model compound | |||||||||

| Acetic acid | 650 | 5.58 | GHSV = 13,000 h−1 | FDB | Ni/Al2O3 | CP | 46 | - | [54] 2005 |

| 700 | 7.5:1 | LHSV = 5.1 h−1 | FB | Ni/La2O3 Co/La2O3 Ni-Co/La2O3 | WI | 96.9–100 | - | [55] 2016 | |

| 800 | 3 | WHSV = 5 h−1 | FB | Ni/CeO2-ZnO | CP & WI | - | 57.8:69.4 | [56] 2020 | |

| Ethanol | 500 | 3 | GHSV = 51,700 h−1 | FB | Co/α-Al2O3 | WI & MM | 86 | 64 | [57] 2019 |

| 500 | 1.5 | WHSV = 2773 h−1 | FB | Ni/Al2O3-TiO2 | WI | 93 | 88 | [58] 2017 | |

| 450 | 5 | WHSV = 0.19–2.88 h−1 | FB | Co/CeO2 | - | 97.1 | 93.3 | [59] 2017 | |

| 600 | 6 | GHSV = 10,432 mL/g·h | FB | Ni/CeO2-MgO | Dip-coating technique | 100 | 70 | [60] 2017 | |

| Acetone | 700 | 9 | LHSV = 850 h−1 | FB | Ce-Ni/Ce | WI | - | 72 | [61] 2015 |

| Phenol | 600 | 5 | GHSV = 4968 h−1 | FB | Ni/Al2O3 | WI | 94.7 | 80.8 | [62] 2022 |

| Glycerol | 575 | 3 | WHSV = 0.85 h−1 | FB | 20Ni-20Co HTl c | CP | - | 97 | [63] 2012 |

| Bio-oil | |||||||||

| Ethanol and phenol (sBO a) | 600 | 2.65 | GHSV = 54,000 h−1 | FB | NiO/Al2O3 | WI | 81 | 66 | [64] 2015 |

| Acetic acid -hydroxy acetone, furfural and phenol a | 600 | 4 2.67 13.2 11 | - | FB | Ni/SBA-15 Ni-Cu/SBA-15 Ni-Co/SBA-15 Ni-Cr/SBA-15 | WI | 91.5–98.4 | >95 | [65] 2019 |

| Acetic acid, Cresol and Benzyl Ether a | 650–810 | 3 and 6 | GHSV = 500:11,790 h−1 | FB | Commercial Ni-based catalyst d | - | - | 70:90 | [66] 1999 |

| Aqueous fraction a | 800 | 4.9 | - | FB | Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 | WI | - | 69.7 | [41] 2010 |

| Acetic acid, Acetone and Glycerol a | 600–800 | 4 | - | FB | Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 & La-Promoted Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 | CP & WI | 60–85 | 42–70 | [42] 2016 |

| Ethanol, acetone, acetic acid, and phenol a | 700 | 9 | LHSV = 850 h−1 | FB | Ni/Al2O3 modified by Mg, Ce and Co | WI | 92.3 | - | [61] 2015 |

| Fresh aqueous fraction of bio-oil a | 700 | 2 | ST = 0.22 gcatalyst/h·gbio-oil | FDB | Ni/α-Al2O3 & Ni/La2O3-Al2O3 | WI | 100 | 96 | [67] 2012 |

| Raw bio-oil (rBO b) | 550–700 | 6 | ST = 0.10 gcatalyst·h/gbio-oil. | FDB | Ni/La2O3-αAl2O3 | WI | 100 | 88 | [32] 2018 |

| 800 | 2 | WHSV = 0.5 h−1 | FB | Fe/olivine | WI | 97.2 | 79.3 | [68] 2016 | |

| 450 | 17 | GHSV = 6000 h−1 | FB | Ni/HZSM-5 Zeolite | WI | ≈100 | 90 | [69] 2011 | |

| 800 | - | WHSV = 1.7 h−1 | FB | Ni/UGSO | SSI | ≈100 | 94 | [70] 2018 | |

| Feedstock | BFM | Prep. Method | Reactor | Operating Conditions | No. of Cycles (-) | H2 Purity (%) c | H2 Yield (%) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (°C) | S/C | WHSV (h−1) | ||||||||

| Model compound | ||||||||||

| Acetic acid | Ni/CaO-La2O3 | Sol–gel | FB | 650 | 3 | 0.63 | 9 | 92.2/85 | 81 | [82] 2017 |

| Ni/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 | WI | FB | 650 | 3 | 1.18 | 20 | 96/83 | 78 | [83] 2019 | |

| Ni/CeO2-ZrO2-CaO | WI | FB | 550 | 4 | 0.48 | 15 | 95/90 | 80 | [84] 2020 | |

| Ni/CexZr1−x O2-CaO | Sol–gel | FB | 550 | 4 | - | 15 | 98/88 | - | [85] 2017 | |

| Ethanol | Ni/Al2O3-CaO | CP | FB | 500 | 4 | - | 10 | 96/90 | 73.5 | [86] 2020 |

| NiO/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 | CP | FB | 600 | 2 | 0.6 | 10 | 87/85 | 70 | [87] 2019 | |

| Ce-Ni/ MCM41/CaO | WI | FB | 600 | 3 | 1.99 | 1 | 90 | 94 | [88] 2012 | |

| Phenol | Ni/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 | CP | FB | 500–650 | 11 | - | 50 | 98.8/96 | 78 | [89] 2020 |

| Ni-M/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 (M = Cu, Co, and Ce) | WI | FB | 650 | 3 | - | 5 | 69.7/- | 62.3 | [11] 2020 | |

| Glycerol | Co-Cu/CaO | CP | FB | 525 | 4 | 3.41 | 10 | 99.2/97.5 | 81 | [90] 2017 |

| NiO/CaO-Al2O3 | CP | FB | 550 | 3 | - | 5 | 90/80 | - | [91] 2015 | |

| NiO/CaO-Ca9Al6O18 | CP | FB | 550 | 9 | 1.55 | 5 | 98/98 | 91 | [75] 2017 | |

| Ni/CaO-FA | WI | FB | 550 | 3 | 1.72 | 20 | 97/96 | 90 | [92] 2020 | |

| Ni/CaO-UGSO | WI | FB | 550 | 3 | 1.55 | 2 | 95/95 | 90 | [93] 2020 | |

| Bio-oil | ||||||||||

| Acetic acid and acetone (sBO a) | Pd-Ni/Co-Dolomite | WI | FDB | 475–725 | 3.33–6.67 | 0.6757–1.3158 | 1 | 99.2– 99.4 | 83.3– 88.6 | [94] 2016 |

| Acetic acid, acetone, phenol, furfural and 1-butanol a | Ni-Co/Olivine-Dolomite | WI | FB | 575 | 7 | 0.8–3.8 | 3 | 99/97 | 70 | [95] 2020 |

| Ethanol, acetic acid, acetone and phenol a | Ce-Ni-Co/ Al2O3-CaO | WI | FB | 700 | 9 | 0.23 | 1 | 93.3 | 83.8 | [96] 2015 |

| Acetic acid, acetone, ethanol, and phenol a | Ni/CaO-UGSO | WI | FB | 550 | 3 | 1.408 | 1 | 96.2 | 90 | [97] 2024 |

| Acetic acid, acetone, ethanol, and phenol a | Ni/CaO-CeO2-ZrO2 | WI | FB | 600 | 3 | 1.408 | 10 | 94/90 | 80 | [98] 2025 |

| (rBO b) | Ni/CeO2-ZrO2-CaO | WI | FB | 550 | 4 | 0.48 | 15 | 90/89 | 77 | [84] 2020 |

| NiAl2O4 spinel/Dolomite | CP | FB & FDB | 600 | 3.4 | 6.67 | 10 | 99/95 | 69 | [99] 2023 | |

| Ce-Ni-Co/Al2O3-CaO | WI | FB | 750 | 12 | 0.15 | 1 | 90 | 85 | [100] 2023 | |

| Hybrid Material (SESR Feedstock) | Prep. Method | Conditions | CO2 Capture Capacity (gCO2/gsorbent) | SESR Conditions | H2 Purity (%) | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonation | Calcination | No. of Cycles | 1st Cycle | Last Cycle | Reaction | Regeneration | No. of Cycles | 1st Cycle | Last Cycle | |||

| Co/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 (Glycerol) | WI | 550 °C, 20% CO2/N2, 40 min | 700 °C, 100% N2, 60 min | 10 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 525 °C, S/C: 4, FR:0.02 mL/min | 700 °C, 100% Ar, 60 min | 50 | 96 | 94 | [138] |

| Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 + CaO (Mechanical mixture) (sBO a) | WI | 600 °C, 15% CO2 + 9.5% H2O/N2, 25 min | 750 °C, 100% N2, 40 min | 15 | 0.37 | 0.22 | - | - | - | - | - | [98] |

| Ni/CaO-CeO2-ZrO2 (sBO a) | WI + HT | 600 °C, 15 vol.% CO2 + 9.5% H2O/N2, 25 min | 750 °C, 100% N2, 40 min | 15 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 600 °C, S/C: 3, WHSV: 1.408 h−1 | 750 °C, 100% Ar, 20 min | 10 | 94 | 90 | [98] |

| Ni/CaO-CeO2-ZrO2 (Acetic acid) | SG | 600 °C,10% CO2/Ar, 40 min | 900 °C, 100% Ar | 15 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 550 °C, S/C: 4, FR: 0.016 mL/min | 700 °C, 100% N2, 60 min | 15 | 98 | 88 | [85] |

| Ni-Al2O3/CaO pellet b (Ethanol) | SG + CT | 850 °C, 70% CO2/N2, 5 min | 850 °C, 100% N2, 5 min | 100 | 0.57 | 0.21 | 650 °C, S/E = 4, FR: 0.08 mL/min | 900 °C, 100% N2, 15 min | 10 | 95 | 90 | [139] |

| Ni/CaO-Al2O3 (Ethanol) | CP | 600 °C, 15% CO2/N2, 30 min | 900 °C, 100% N2, 30 min | 20 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 600 °C, S/E: 4, FR: 0.05 mL/min | 900 °C, 10% H2/N2, 15 min | 10 | 96 | 90 | [86] |

| Ni/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 (Phenol) | CP + CAT | - | - | - | - | - | 575 °C, FR: 0.04 mL/min | 800 °C, 100% N2, 30 min | 50 | 98 | 98 | [140] |

| Ni/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 (Glycerol) | HT | - | - | - | - | - | 550 °C, S/C = 4, FR: 0.02 mL/min | 800 °C, 100% N2, 30 min | 20 | 99 | 99 | [125] |

| Ni/CaO-Ca12Al14O33 (Glycerol) | WI + CM | 650 °C, 20% CO2/N2, 30 min | 750 °C, 100% N2, 30 min | 15 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 600 °C, S/C:3, WHSV: 2.59 h−1 | 700 °C, 100% Ar | 9 | 93 | 91 | [126] |

| Sorbent | Waste | Prep. Method | Carbonation Conditions | Calcination Conditions | Cycles | Sorption Capacity at Last Cycle (gCO2/gsorbent) | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO-24% SiO2 | Husk ash | DM | 700 °C, 15% CO2, 25 min | 950 °C, 100% N2, 10 min | 10 | 0.44 | - | [143] 2012 |

| CaO-SiO2 | Husk ash | WI | 700 °C, 15% CO2, 15 min | 850 °C, 100% N2, 20 min | 20 | 0.39 | 25 | [144] 2012 |

| CaO-10% UGSO | UGSO | WI | 650 °C, 15% CO2, 9.5% H2O, 20 min | 750 °C, 100% Ar, 40 min | 18 | 0.54 | 30.5 | [93] 2020 |

| CaO-50% FA | Fly ash | CP | 700 °C, 15% CO2, 20 min | 850 °C, 100% N2, 10 min | 20 | 0.37 | 16.41 | [145] 2017 |

| CaO–CS | Carbide slag (CS) | - | 750 °C, 100% CO2, 60 min | 900 °C, 100% N2, 90 min | 20 | 0.42 | 20.8 | [146] 2016 |

| CaO–Nano SiO2 | Photovoltaic waste (SiCl4) | DM | 700 °C, 100% CO2, 5 min | 900 °C, 100% N2, 3 min | 30 | 0.32 | 7.46 | [147] 2016 |

| CaO-10% FA | Fly ash | WI | 650 °C, 15% CO2, 9.5% H2O, 30 min | 750 °C, 100% N2, 40 min | 20 | 0.45 | 28.95 | [92] 2020 |

| Ni-CaO-10% FA | Fly ash | WI | 550 °C, 15% CO2, 9.5% H2O, 30 min | 800 °C, 100% N2, 20 min | 20 | 0.57 | 23.83 | [92] 2020 |

| Ni-CaO-UGSO | UGSO | WI | 650 °C, 15% CO2, 9.5% H2O, 25 min | 750 °C, 100% N2, 40 min | 18 | 0.45 | 10.5 | [97] 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elsaka, E.; Mercier, E.; Iliuta, M.C. Conventional and Intensified Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Renewable Hydrogen Production: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Catalysts 2026, 16, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010059

Elsaka E, Mercier E, Iliuta MC. Conventional and Intensified Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Renewable Hydrogen Production: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsaka, Eslam, Etienne Mercier, and Maria C. Iliuta. 2026. "Conventional and Intensified Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Renewable Hydrogen Production: Challenges and Future Perspectives" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010059

APA StyleElsaka, E., Mercier, E., & Iliuta, M. C. (2026). Conventional and Intensified Steam Reforming of Bio-Oil for Renewable Hydrogen Production: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Catalysts, 16(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010059