Surface-Controlled Photo-Fenton Activity of Cu-Fe Bimetallic Catalysts: Dual Function of Iron on Silica and Alumina Supports

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalyst Characterization

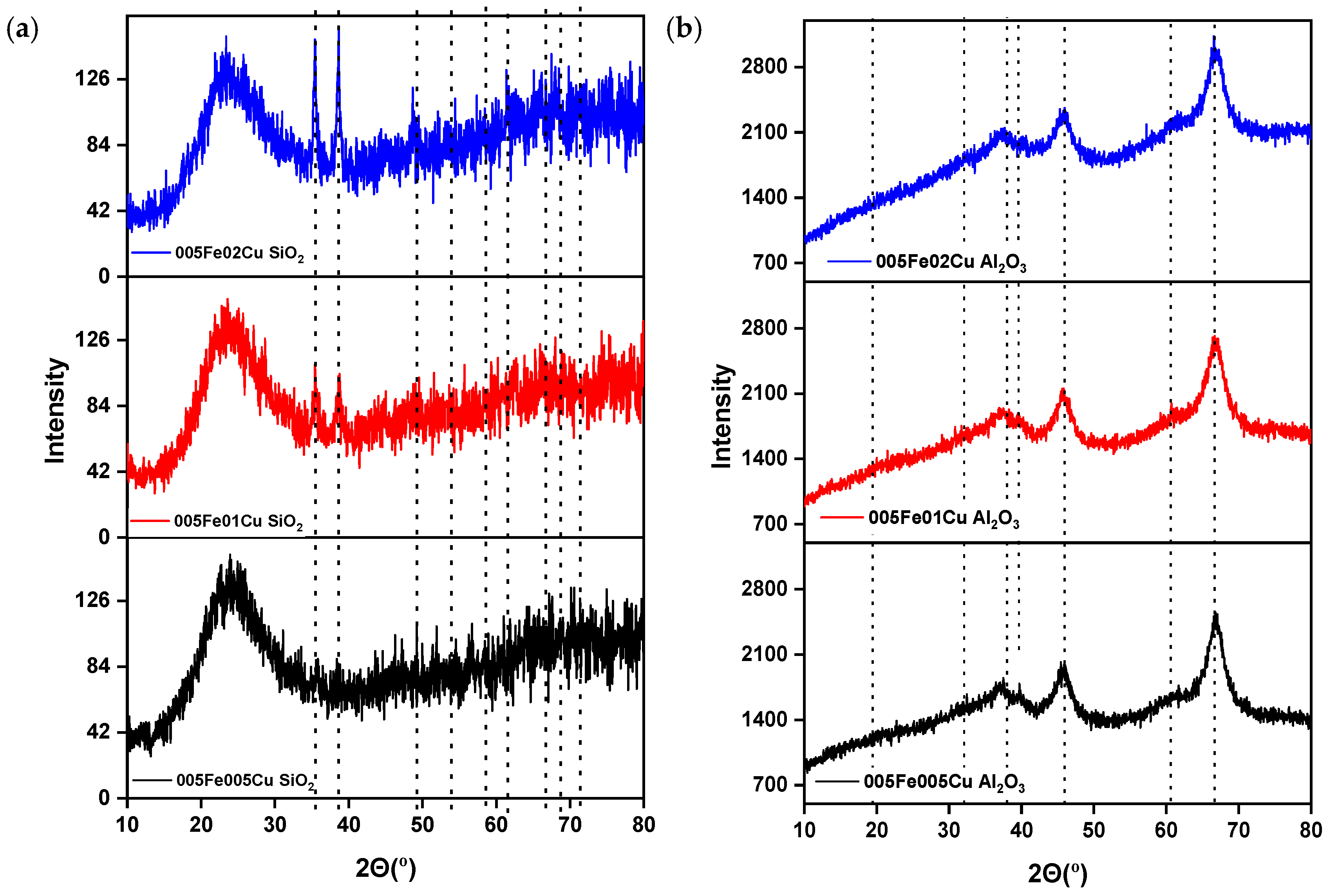

2.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) Analysis

2.1.3. Nitrogen Physisorption and BET Surface Area Analysis

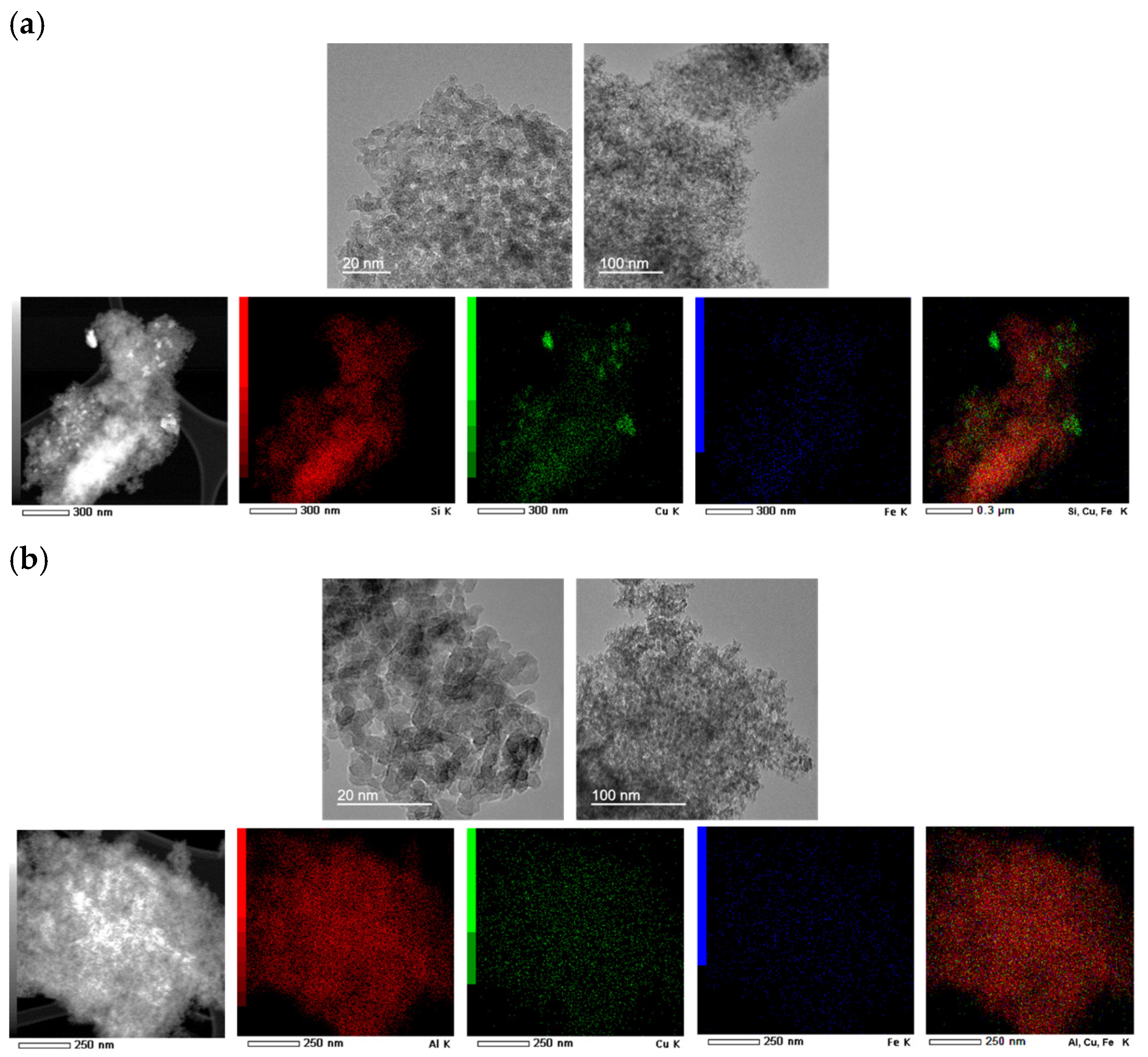

2.1.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

2.1.5. UV-Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS)

2.1.6. Photoluminescence (PL) Analysis

2.1.7. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy

2.2. Evaluation of Fenton-like and Photo-Fenton-like Catalysis Using Coumarin

2.2.1. Catalytic Tests

2.2.2. Metal Leaching Analysis

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Preparation of Catalysts

3.2.1. Preparation of Silica-Supported Catalysts

3.2.2. Preparation of Alumina-Supported Catalysts

3.3. Materials Characterization

3.4. Catalytic Evaluation of Hydroxyl Radical Generation Using Coumarin as a Probe

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badea, S.-L.; Niculescu, V.-C. Recent Progress in the Removal of Legacy and Emerging Organic Contaminants from Wastewater Using Metal–Organic Frameworks: An Overview on Adsorption and Catalysis Processes. Materials 2022, 15, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.M.A.; Mansano, A.S.; Holanda, C.A.; Pinto, T.S.; Reis, J.B.; Azevedo, E.B.; Verbinnen, R.T.; Viana, J.L.; Franco, T.C.R.S.; Vieira, E.M. Occurrence and Environmental Risk Assessment of Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Brazilian Surface Waters. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahrouei, A.E.; Vakili, S.; Zandifar, A.; Pourebrahimi, S. From wastewater to clean water: Recent advances on the removal of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and sulfamethoxazole antibiotics from water through adsorption and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 119029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandis, P.K.; Kalogirou, C.; Kanellou, E.; Vaitsis, C.; Savvidou, M.G.; Sourkouni, G.; Zorpas, A.A.; Argirusis, C. Key Points of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) for Wastewater, Organic Pollutants and Pharmaceutical Waste Treatment: A Mini Review. ChemEngineering 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvulescu, V.I.; Epron, F.; Garcia, H.; Granger, P. Recent Progress and Prospects in Catalytic Water Treatment. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2981–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.P.; Nunes, M.I. Recent trends and developments in Fenton processes for industrial wastewater treatment—A critical review. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 110957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, F.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C.; Ruotolo, L.A.M. Critical review of Fenton and photo-Fenton wastewater treatment processes over the last two decades. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 13995–14032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qiao, J.; Sun, Y.; Dong, H. The profound review of Fenton process: What’s the next step? J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziembowicz, S.; Kida, M. Limitations and future directions of application of the Fenton-like process in micropollutants degradation in water and wastewater treatment: A critical review. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 134041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Pillai, S.C. Heterogeneous Fenton catalysts: A review of recent advances. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsov, A.V. Advancing Fenton and photo-Fenton water treatment through the catalyst design. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 372, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Lai, C.; Yi, H.; Huo, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Xu, F.; Yan, H.; Hu, S.; Luo, Y. Confinement strategies for the design of efficient heterogeneous Fenton-like catalysts: From nano-space to atomic scale. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 522, 216241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Guo, S.; Wang, D.; An, Q. Fenton-Like Reaction: Recent Advances and New Trends. Chem.-Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202304337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-S.; Gurol, M.D. Catalytic Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide on Iron Oxide: Kinetics, Mechanism, and Implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duesterberg, C.K.; Waite, T.D. Process Optimization of Fenton Oxidation Using Kinetic Modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 4189–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dong, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Meng, D. A review on Fenton process for organic wastewater treatment based on optimization perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Kan, Y.; Xu, X. Stability and regeneration of metal catalytic sites with different sizes in Fenton-like system. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.-L.; Wang, W.; Song, Y.; Tang, R.; Hu, Z.-H.; Zhou, X.; Yu, H.-Q. Expanding the pH range of Fenton-like reactions for pollutant degradation: The impact of acidic microenvironments. Water Res. 2025, 270, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Sheng, M.; Niu, W.; Fei, Y.; Li, D. Regeneration and reuse of iron catalyst for Fenton-like reactions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1446–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, A.; Hajjaoui, H.; Boumya, W.; Elmouwahidi, A.; Baillón-García, E.; Abdennouri, M.; Barka, N. Recent trends in magnetic spinel ferrites and their composites as heterogeneous Fenton-like catalysts: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 121971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.; Singh, A.K.; Kim, H.; Lichtfouse, E.; Sharma, V.K. Treatment of organic pollutants by homogeneous and heterogeneous Fenton reaction processes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Xi, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, G.; He, H. Strategies for enhancing the heterogeneous Fenton catalytic reactivity: A review. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 255, 117739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.-P.; Wu, W.D.; Wu, Z. Nanostructured semiconductor supported iron catalysts for heterogeneous photo-Fenton oxidation: A review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 15513–15546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Ganiyu, S.O.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Mousset, E.; Olvera-Vargas, H.; Trellu, C.; Zhou, M.; Oturan, M.A. Recent advances in electro-Fenton process and its emerging applications. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 887–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Vargas, H.; Trellu, C.; Nidheesh, P.V.; Mousset, E.; Ganiyu, S.O.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Zhou, M.; Oturan, M.A. Challenges and opportunities for large-scale applications of the electro-Fenton process. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuponnusami, A.; Muthukumar, K. A review on Fenton and improvements to the Fenton process for wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, J.A.; Martínez, F.; Molina, R. Effect of Ultrasound on the Properties of Heterogeneous Catalysts for Sono-Fenton Oxidation Processes. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2008, 11, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.C.; Oliveira, L.C.A.; Murad, E. Iron oxide catalysts: Fenton and Fentonlike reactions—A Review. Clay Miner. 2012, 47, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lin, Z.-R.; Ma, X.; Dong, Y.-H. Catalytic activity of different iron oxides: Insight from pollutant degradation and hydroxyl radical formation in heterogeneous Fenton-like systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 352, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, Q.; Deng, F.; Ni, Z.; Lin, Q.; Cheng, L.; Chen, X.; Qiu, R.; Zhu, R. The differences in heterogeneous Fenton catalytic performance and mechanism of various iron minerals and their influencing factors: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 325, 124702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Q. Catalytic activity and mechanism of typical iron-based catalysts for Fenton-like oxidation. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 136972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mao, Y.; Tang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, F. Synthesis of Ag/AgCl/Fe-S plasmonic catalyst for bisphenol A degradation in heterogeneous photo-Fenton system under visible light irradiation. Chin. J. Catal. 2017, 38, 1726–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, A.; Navgire, M.; Sarma, K.C.; Gogoi, P. Fe3O4-CeO2 metal oxide nanocomposite as a Fenton-like heterogeneous catalyst for degradation of catechol. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 311, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Choi, I.-S.; Kim, S.H. Metal oxides for Fenton reactions toward radical-assisted water treatment: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 142, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Wu, G.; Lian, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. Iron encapsulated in boron and nitrogen codoped carbon nanotubes as synergistic catalysts for Fenton-like reaction. Water Res. 2016, 101, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Wang, J. Degradation of sulfamethazine using Fe3O4-Mn3O4/reduced graphene oxide hybrid as Fenton-like catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 324, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubir, N.A.; Yacou, C.; Motuzas, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.S.; Diniz da Costa, J.C. The sacrificial role of graphene oxide in stabilising a Fenton-like catalyst GO–Fe3O4. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 9291–9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Show, P.L.; Ivanets, A.; Luo, D.; Wang, C. MXenes as heterogeneous Fenton-like catalysts for removal of organic pollutants: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Q.; Wen, Y.; Liu, W. Fe-g-C3N4/graphitized mesoporous carbon composite as an effective Fenton-like catalyst in a wide pH range. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 201, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, R.; Chaibakhsh, N.; Zanjanchi, M.A.; Moradi-Shoeili, Z. Fabrication of ZnO/FeVO4 heterojunction nanocomposite with high catalytic activity in photo-Fenton-like process. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 817, 152702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, D.; Hu, W.; Li, Y. Efficient generation of singlet oxygen on Fe2O3/MoO3 Z-type heterojunction for removal of ciprofloxacin from water via photo-electro-Fenton-like system. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, S.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Megharaj, M.; Naidu, R. Nanoscale zero-valent iron as a catalyst for heterogeneous Fenton oxidation of amoxicillin. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 255, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, R.; Kurosu, S.; Suzuki, M.; Kawase, Y. Hydroxyl radical generation by zero-valent iron/Cu (ZVI/Cu) bimetallic catalyst in wastewater treatment: Heterogeneous Fenton/Fenton-like reactions by Fenton reagents formed in-situ under oxic conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1537–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Khan, J.A.; Sayed, M.; Iqbal, J.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Muhammad, N.; Polychronopoulou, K.; Hussain, S.; Imran, M.; Murtaza, B.; et al. Nano-zerovalent copper as a Fenton-like catalyst for the degradation of ciprofloxacin in aqueous solution. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2020, 37, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Chen, S.; Quan, X.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced Fenton-like catalysis by iron-based metal organic frameworks for degradation of organic pollutants. J. Catal. 2017, 356, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Fan, W.; Feng, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Dong, Z.; Li, X. A critical review on metal complexes removal from water using methods based on Fenton-like reactions: Analysis and comparison of methods and mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, S.; Quan, H.; Hua, L.; Luo, X.; Guo, L. Heterogeneous Fenton-like catalysis of Fe-MOF derived magnetic carbon nanocomposites for degradation of 4-nitrophenol. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 49024–49030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, J. MOF-derived three-dimensional flower-like FeCu@C composite as an efficient Fenton-like catalyst for sulfamethazine degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 375, 122007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Yu, G.; Zhang, L.; Hu, C.; Sun, Y. 4-Phenoxyphenol-Functionalized Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanosheets: A Metal-Free Fenton-Like Catalyst for Pollutant Destruction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokare, A.D.; Choi, W. Review of iron-free Fenton-like systems for activating H2O2 in advanced oxidation processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 275, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Ramírez, E.G.; Theng, B.K.G.; Mora, M.L. Clays and oxide minerals as catalysts and nanocatalysts in Fenton-like reactions—A review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 47, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Fard, M.S. A critical review in Fenton-like approach for the removal of pollutants in the aqueous environment. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Multivalent metal catalysts in Fenton/Fenton-like oxidation system: A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Mata, A.G.; Velazquez-Martínez, S.; Álvarez-Gallegos, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Hernández-Pérez, J.A.; Ghanbari, F.; Silva-Martínez, S. Recent Overview of Solar Photocatalysis and Solar Photo-Fenton Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Photoenergy 2017, 2017, 8528063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, R.; Chohadia, A.K.; Jain, A.; Punjabi, P.B. Fenton and Photo-Fenton Processes. In Advanced Oxidation Processes for Waste Water Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 49–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.M.; Roghabadi, F.A.; Ahmadi, V. Solid-supported photocatalysts for wastewater treatment: Supports contribution in the photocatalysis process. J. Sol. Energy 2023, 255, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Ferreira-Neto, E.P.; Khan, A.A.; Medeiros, I.P.M.; Wender, H. Supported nanostructured photocatalysts: The role of support-photocatalyst interactions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2022, 22, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šuligoj, A.; Ristić, A.; Dražić, G.; Pintar, A.; Zabukovec Logar, N.; Novak Tušar, N. Bimetal Cu-Mn porous silica-supported catalyst for Fenton-like degradation of organic dyes in wastewater at neutral pH. Catal. Today 2020, 358, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadian, N.; Liu, S.; Asadi, A.; Shahlaei, M.; Moradi, S. Enhanced heterogeneous Fenton oxidation of organic pollutant via Fe-containing mesoporous silica composites: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 321, 114896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, G. Chemistry of Dawsonites and Application in Catalysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.A.; Hasan, M.A.; Zaki, M.I. Dawsonite-Type Precursors for Catalytic Al, Cr, and Fe Oxides: Synthesis and Characterization. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 6797–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, G.; Zhao, R.; Liu, C. Fabrication of high-surface-area γ-alumina by thermal decomposition of AACH precursor using low-temperature solid-state reaction. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012, 47, 4271–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djinović, P.; Ristić, A.; Žumbar, T.; Dasireddy, V.D.B.C.; Rangus, M.; Dražić, G.; Popova, M.; Likozar, B.; Zabukovec Logar, N.; Novak Tušar, N. Synergistic effect of CuO nanocrystals and Cu-oxo-Fe clusters on silica support in promotion of total catalytic oxidation of toluene as a model volatile organic air pollutant. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 268, 118749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žumbar, T.; Arčon, I.; Djinović, P.; Aquilanti, G.; Žerjav, G.; Pintar, A.; Ristić, A.; Dražić, G.; Volavšek, J.; Mali, G.; et al. Winning Combination of Cu and Fe Oxide Clusters with an Alumina Support for Low-Temperature Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 28747–28762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, M.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Il Lee, T. Sunlight driven decomposition of toxic organic compound, coumarin, p-nitrophenol, and photo reduction of Cr(VI) ions, using a bridge structure of Au@CNT@TiO2 nanocomposite. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 272, 118991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Tong, L.; Li, J.; Luo, R.; Qi, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Iron–copper bimetallic nanoparticles supported on hollow mesoporous silica spheres: An effective heterogeneous Fenton catalyst for orange II degradation. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 69593–69605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Y. Synergistic effects in iron-copper bimetal doped mesoporous γ-Al2O3 for Fenton-like oxidation of 4-chlorophenol: Structure, composition, electrochemical behaviors and catalytic performance. Chemosphere 2018, 203, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Yang, H. Tailoring the Electronic Structure of Mesoporous Spinel γ-Al2O3 at Atomic Level: Cu-Doped Case. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 14299–14315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalim, M.; Shah, M.A. Role of oxygen vacancies and porosity in enhancing the electrochemical properties of Microwave synthesized hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanostructures for supercapacitor application. Vacuum 2023, 210, 111903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccuzzi, F.; Coluccia, S.; Martra, G.; Ravasio, N. Cu/SiO2 and Cu/SiO2–TiO2 Catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 184, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Que, Z.; Pérez-Vidal, H.; Torres-Torres, G.; Arévalo-Pérez, J.C.; Silahua Pavón, A.A.; Cervantes-Uribe, A.; Espinosa de los Monteros, A.; Lunagómez-Rocha, M.A. Treatment of phenol by catalytic wet air oxidation: A comparative study of copper and nickel supported on γ-alumina, ceria and γ-alumina–ceria. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 8463–8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Santhosh Kumar, M.; Brückner, A. Reduction of N2O with CO over FeMFI zeolites: Influence of the preparation method on the iron species and catalytic behavior. J. Catal. 2004, 223, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahiduzzaman, M.; Wang, S.; Schnee, J.; Vimont, A.; Ortiz, V.; Yot, P.G.; Retoux, R.; Daturi, M.; Lee, J.S.; Chang, J.-S.; et al. A High Proton Conductive Hydrogen-Sulfate Decorated Titanium Carboxylate Metal−Organic Framework. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5776–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žumbar, T.; Ristić, A.; Dražić, G.; Lazarova, H.; Volavšek, J.; Pintar, A.; Zabukovec Logar, N.; Novak Tušar, N. Influence of Alumina Precursor Properties on Cu-Fe Alumina Supported Catalysts for Total Toluene Oxidation as a Model Volatile Organic Air Pollutant. Catalysts 2021, 11, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaturyan, A.A.; Cherkasova, S.O.; Budnyk, A.P. Theoretical and experimental characterization of Cu-doped amorphous silicate glass. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Yang, H. Insights into the nature of Cu doping in amorphous mesoporous alumina. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 14592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baronskiy, M.; Rastorguev, A.; Zhuzhgov, A.; Kostyukov, A.; Krivoruchko, O.; Snytnikov, V. Photoluminescence and Raman spectroscopy studies of low-temperature γ-Al2O3 phases synthesized from different precursors. Opt. Mater. 2016, 53, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraban, A.P.; Samarin, S.N.; Prokofiev, V.A.; Dmitriev, V.A.; Selivanov, A.A.; Petrov, Y. Luminescence of SiO2 layers on silicon at various types of excitation. J. Lumin. 2019, 205, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Nakatsuka, M. Spectroscopic properties and quantum yield of Cu-doped SiO2 glass. J. Lumin. 1997, 75, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitianu, A.; Crisan, M.; Meghea, A.; Rau, I.; Zaharescu, M. Influence of the silica based matrix on the formation of iron oxide nanoparticles in the Fe2O3–SiO2 system, obtained by sol–gel method. J. Mater. Chem. 2002, 12, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazzesi, G.; Nicosia, D.; Devadas, M.; Kröcher, O.; Elsener, M.; Wokaun, A. Investigation of HNCO adsorption and hydrolysis on Fe-ZSM5. Catal. Lett. 2007, 115, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervasini, A.; Manzoli, M.; Martra, G.; Ponti, A.; Ravasio, N.; Sordelli, L.; Zaccheria, F. Dependence of Copper Species on the Nature of the Support for Dispersed CuO Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 7851–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Wu, T.; Wang, G. Surface structure and catalytic behavior of silica-supported copper catalysts prepared by impregnation and sol–gel methods. Appl. Catal. A 2003, 239, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Characterization and catalytic behavior of silica-supported copper catalysts prepared by impregnation and ion-exchange methods. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2008, 93, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.L.; Resasco, D.E. Effects of the support and the addition of a second promoter on potassium chloride-copper(II) chloride catalysts used in the oxychlorination of methane. Appl. Catal. 1989, 46, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandri, V.; Gardner, J.M.; Jonsson, M. Coumarin as a Quantitative Probe for Hydroxyl Radical Formation in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 6667–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žerjav, G.; Albreht, A.; Vovk, I.; Pintar, A. Revisiting terephthalic acid and coumarin as probes for photoluminescent determination of hydroxyl radical formation rate in heterogeneous photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. A 2020, 598, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Segura, S.; Brillas, E.; Cornejo-Ponce, L.; Salazar, R. Effect of the Fe3+/Cu2+ ratio on the removal of the recalcitrant oxalic and oxamic acids by electro-Fenton and solar photoelectro-Fenton. Sol. Energy 2016, 124, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, R.; Brillas, E.; Sirés, I. Finding the best Fe2+/Cu2+ combination for the solar photoelectro-Fenton treatment of simulated wastewater containing the industrial textile dye Disperse Blue 3. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 115–116, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidruk, R.; Landau, M.V.; Herskowitz, M.; Ezersky, V.; Goldbourt, A. Control of surface acidity and catalytic activity of γ-Al2O3 by adjusting the nanocrystalline contact interface. J. Catal. 2011, 282, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Ma, Z.; Li, T.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Xing, W.; Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Yan, Z. Relationship between Surface Chemistry and Catalytic Performance of Mesoporous γ-Al2O3 Supported VOx Catalyst in Catalytic Dehydrogenation of Propane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 25979–25990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.; Meziane, D.; Wojcieszak, R.; Dumeignil, F.; Boukherroub, R.; Szunerits, S. Plasmon-Induced Electrocatalysis with Multi-Component Nanostructures. Materials 2018, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periyasamy, M.; Sain, S.; Sengupta, U.; Mandal, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kar, A. Bandgap tuning of photo Fenton-like Fe3O4/C catalyst through oxygen vacancies for advanced visible light photocatalysis. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4843–4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak Tušar, N.; Maučec, D.; Rangus, M.; Arčon, I.; Mazaj, M.; Cotman, M.; Pintar, A.; Kaučič, V. Manganese Functionalized Silicate Nanoparticles as a Fenton-Type Catalyst for Water Purification by Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOP). Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafficher, R.; Digne, M.; Salvatori, F.; Boualleg, M.; Colson, D.; Puel, F. Ammonium aluminium carbonate hydroxide NH4Al(OH)2CO3 as an alternative route for alumina preparation: Comparison with the classical boehmite precursor. Powder Technol. 2017, 320, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafficher, R.; Digne, M.; Salvatori, F.; Boualleg, M.; Colson, D.; Puel, F. Development of new alumina precipitation routes for catalysis applications. J. Cryst. Growth 2017, 468, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, T.A.; Fierro, J.L.G.; Pawelec, B.; Nava, R.; Klimova, T.; Fuentes, G.A.; Halachev, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Ti-HMS and CoMo/Ti-HMS Oxide Materials with Varying Ti Content. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 4062–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuligoj, A.; Trendafilova, I.; Maver, K.; Pintar, A.; Ristić, A.; Dražić, G.; Abdelraheem, W.H.M.; Jagličić, Z.; Arčon, I.; Zabukovec Logar, N.; et al. Multicomponent Cu–Mn–Fe silica supported catalysts to stimulate photo-Fenton-like water treatment under sunlight. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louit, G.; Foley, S.; Cabillic, J.; Coffigny, H.; Taran, F.; Valleix, A.; Renault, J.P.; Pin, S. The reaction of coumarin with the OH radical revisited: Hydroxylation product analysis determined by fluorescence and chromatography. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2005, 72, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Crystallite Size (nm) |

|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu SiO2 | - |

| 005Fe01Cu SiO2 | 12.1 |

| 005Fe02Cu SiO2 | 20 |

| Catalyst | Crystallite Size (nm) |

|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu Al2O3 | 4.36 |

| 005Fe01Cu Al2O3 | 3.80 |

| 005Fe02Cu Al2O3 | 4.38 |

| Catalyst | Fe/Si | Cu/Si | Fe/Al | Cu/Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu SiO2 | 0.007 | 0.01 | - | - |

| 005Fe01Cu SiO2 | 0.007 | 0.02 | - | - |

| 005Fe02Cu SiO2 | 0.007 | 0.04 | - | - |

| 005Fe005Cu Al2O3 | - | - | 0.007 | 0.01 |

| 005Fe01Cu Al2O3 | - | - | 0.006 | 0.01 |

| 005Fe02Cu Al2O3 | - | - | 0.007 | 0.02 |

| Catalyst | SBET (m2/g) | Vpore at p/p° = 0.98 (cm3/g) | Average Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu SiO2 | 650 | 1.75 | 18.8 |

| 005Fe01Cu SiO2 | 654 | 1.98 | 21.3 |

| 005Fe02Cu SiO2 | 611 | 2.19 | 24.8 |

| 005Fe005Cu Al2O3 | 286 | 0.55 | 5.3 |

| 005Fe01Cu Al2O3 | 258 | 0.59 | 6.8 |

| 005Fe02Cu Al2O3 | 247 | 0.59 | 7.3 |

| Sample | Bandgap (eV) |

|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu SiO2 | 3.76 |

| 005Fe01Cu SiO2 | 3.56 |

| 005Fe02Cu SiO2 | 3.62 |

| 005Fe005Cu Al2O3 | 3.34 |

| 005Fe01Cu Al2O3 | 3.42 |

| 005Fe02Cu Al2O3 | 3.52 |

| Sample | τ1 (ns) | τ2 (ns) | A1 (%) | A2 (%) | τaverage (ns) | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu Al2O3 | 0.51 | 3.90 | 99.6 | 0.4 | 0.52 | 1.14 |

| 005Fe01Cu Al2O3 | 0.87 | 1.81 | 99.5 | 0.5 | 0.87 | 1.22 |

| 005Fe02Cu Al2O3 | 0.68 | 2.00 | 99.7 | 0.3 | 0.68 | 1.13 |

| 005Fe02Cu SiO2 | 0.66 | 1.79 | 99.5 | 0.5 | 0.67 | 1.15 |

| 01Fe02Cu SiO2 | 0.48 | 1.75 | 99.6 | 0.4 | 0.49 | 1.20 |

| Catalyst | Cu (µg/L) | Fe (µg/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 005Fe005Cu SiO2 | 264 | 6 |

| 005Fe01Cu SiO2 | 185 | 1 |

| 005Fe02Cu SiO2 | 267 | 3 |

| 01Fe005Cu SiO2 | 213 | 15 |

| 01Fe01Cu SiO2 | 258 | 19 |

| 01Fe02Cu SiO2 | 462 | 17 |

| 005Fe005Cu Al2O3 | 83 | 2 |

| 005Fe01Cu Al2O3 | 462 | 1 |

| 005Fe02Cu Al2O3 | 733 | <1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kuruvangattu Puthenveettil, N.; Dražić, G.; Pintar, A.; Novak Tušar, N. Surface-Controlled Photo-Fenton Activity of Cu-Fe Bimetallic Catalysts: Dual Function of Iron on Silica and Alumina Supports. Catalysts 2026, 16, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010034

Kuruvangattu Puthenveettil N, Dražić G, Pintar A, Novak Tušar N. Surface-Controlled Photo-Fenton Activity of Cu-Fe Bimetallic Catalysts: Dual Function of Iron on Silica and Alumina Supports. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuruvangattu Puthenveettil, Nimisha, Goran Dražić, Albin Pintar, and Nataša Novak Tušar. 2026. "Surface-Controlled Photo-Fenton Activity of Cu-Fe Bimetallic Catalysts: Dual Function of Iron on Silica and Alumina Supports" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010034

APA StyleKuruvangattu Puthenveettil, N., Dražić, G., Pintar, A., & Novak Tušar, N. (2026). Surface-Controlled Photo-Fenton Activity of Cu-Fe Bimetallic Catalysts: Dual Function of Iron on Silica and Alumina Supports. Catalysts, 16(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010034