Enhancement of the Peroxidase Activity of Metal–Organic Framework with Different Clay Minerals for Detecting Aspartic Acid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

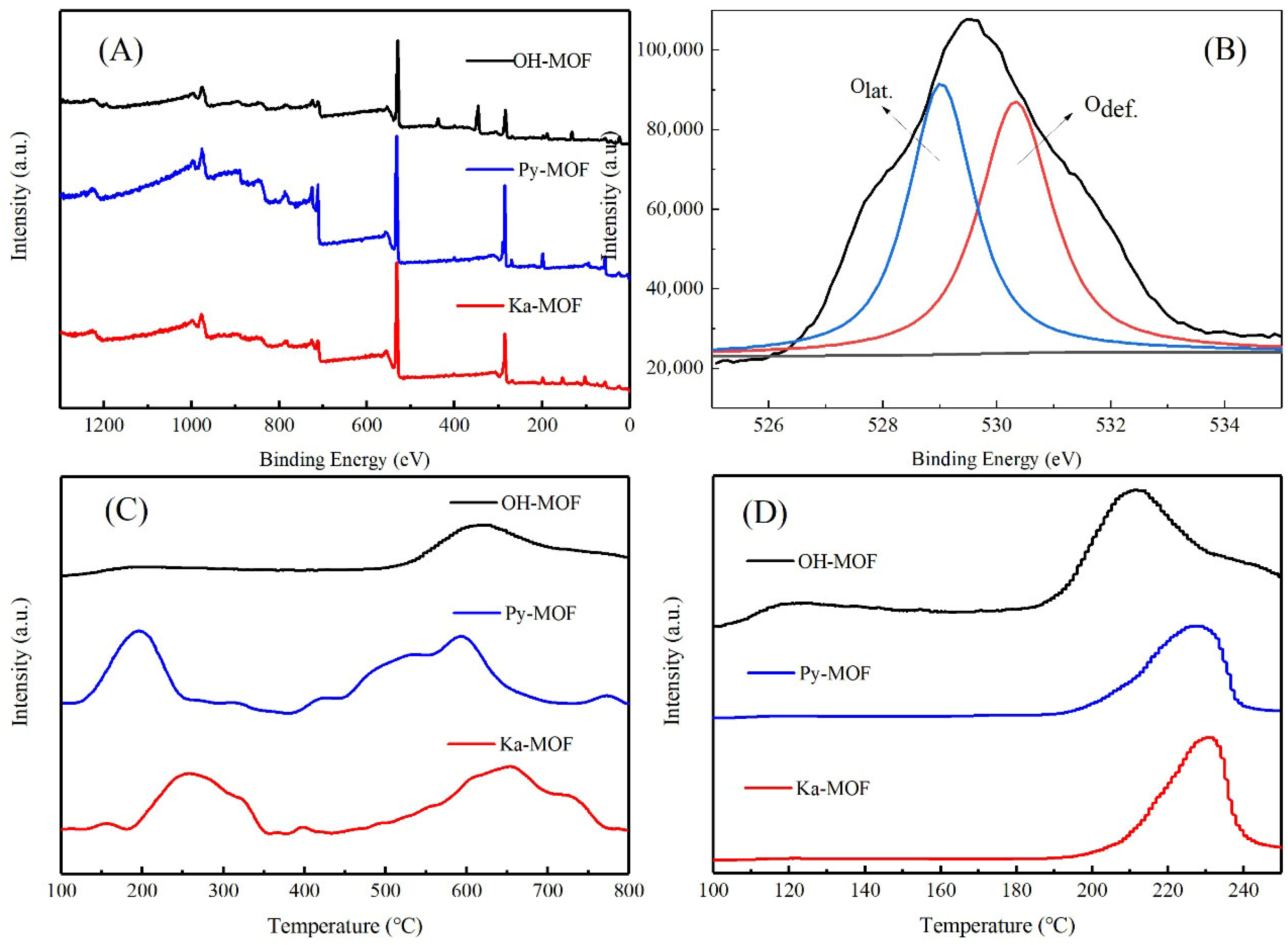

2.1. Structure Characterization of Clay-MOF Catalysts

2.2. Peroxidase Activity of Clay-MOF Catalysts

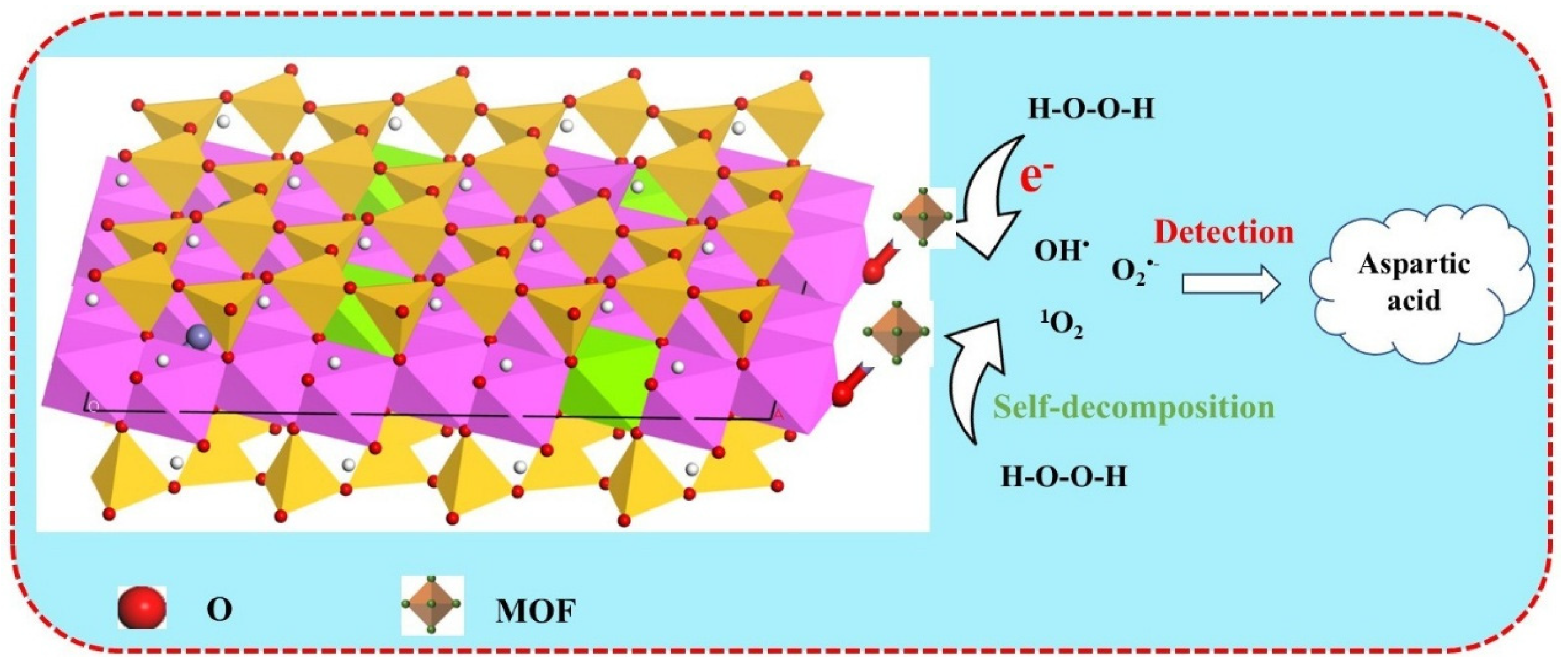

2.3. Possible Mechanisms

2.4. Influences of Various Reaction Conditions

3. Experimental

3.1. Reagents and Chemicals

3.2. Synthesis of Different Iron Aluminate Catalysts

3.3. Characterization of Clay Mineral@MIL-101(Fe) Catalysts

3.4. Study on Peroxidase Activity over Clay Mineral@MIL-101(Fe) Catalysts

3.5. Mechanism of Peroxidase Activity over Clay Mineral@MIL-101(Fe) Catalysts

3.6. Determination of Amino Acids in Aquatic Products

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prasad, B.B.; Pandey, I. Electrochemically imprinted molecular recognition sites on multiwalled carbon-nanotubes/pencil graphite electrode surface for enantioselective detection of d-and l-aspartic acid. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 88, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Chemistry, nutrition, and microbiology of D-amino acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3457–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L. Aspartic acid as a precursor for glutamic acid and glycine. Brain Res. 1974, 67, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekharsky, M.; Yamamura, H.; Kawai, M.; Inoue, Y. Critical difference in chiral recognition of N-Cbz-d/l-aspartic and-glutamic acids by mono-and bis (trimethylammonio)-β-cyclodextrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 5360–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.Z.; Lv, D.Y.; Sun, H.T.; Yang, W. Determination of Laspartic acid by using the Cu (II)-catalyzed oscillating reaction. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2009, 20, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Golden, T.; Peng, T. Poly (4-vinylpyridine)-coated glassy carbon flow detectors. Anal. Chem. 1987, 59, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayadunne, R.; Nguyen, T.T.; Marriott, P.J. Amino acid analysis by using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005, 382, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Hu, X.; Li, K.; Sun, C. Simultaneous determination of ginsenoside (G-Re, G-Rg1, G-Rg2, G-F1, G-Rh1) and protopanaxatriol in human plasma and urine by LC–MS/MS and its application in a pharmacokinetics study of G-Re in volunteers. J. Chromatogr. B 2011, 879, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pundir, C.S.; Lata, S.; Narwal, V. Biosensors for determination of D- and L-amino acids: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 117, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla-Tolós, J.; Moliner-Martínez, Y.; Verdú-Andrés, J.; Casanova-Chafer, J.; Molins-Legua, C.; Campíns-Falcó, P. New optical paper sensor for in situ measurement of hydrogen sulphide in waters and atmospheres. Talanta 2016, 156, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Niu, Q.; Gao, P.; Zhang, G.; Dong, C.; Shuang, S. Gold nanoclusters as fluorescent sensors for selective and sensitive hydrogen sulfide detection. Talanta 2017, 171, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Catalytically active nanomaterials: A promising candidate for artificial enzymes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Lin, F.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B.; Jiang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, J. Multicopper laccase mimicking nanozymes with nucleotides as ligands. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 1352–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.L.; Xu, Q. Metal–organic frameworks as platforms for catalytic applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1703663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Rimoldi, M.; Platero-Prats, A.E.; Chapman, K.W.; Hupp, J.T.; Farha, O.K. Stabilizing a vanadium oxide catalyst by supporting on a metal–organic framework. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 1772–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.D.; Jiang, Z.W.; Wang, D.M.; Huang, C.Z.; Li, Y.F. Fe3O4 and metal–organic framework MIL-101 (Fe) composites catalyze luminol chemiluminescence for sensitively sensing hydrogen peroxide and glucose. Talanta 2018, 179, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.X.; Jia, S.Y.; Wang, F.F.; Wu, S.H.; Song, J.; Liu, Y. Hemin@ metal-organic framework with peroxidase-like activity and its application to glucose detection. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 2761–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Zhao, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Quan, X. Fe3O4-AuNPs anchored 2D metal–organic framework nanosheets with DNA regulated switchable peroxidase-like activity. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 18699–18710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Tian, X.; Guo, F.; Nie, Y.; Dai, C.; Li, Y.; Lu, L. Enhancement of the peroxidase activity of g-C3N4 with different morphologies for simultaneous detection of multiple antibiotics. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 12550–12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Fan, Y.; Du, J.; Song, Z.; Zhao, H. CNT-modified MIL-88 (NH2)-Fe for enhancing DNA-regulated peroxidase-like activity. J. Anal. Test. 2019, 3, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Xiong, N.; Zhu, G. Technology for the remediation of water pollution: A review on the fabrication of metal organic frameworks. Processes 2018, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Y.C.; Viltres, H.; Gupta, N.K.; Acevedo-Pena, P.; Leyva, C.; Ghaffari, Y.; Kim, K.S. Transition metal-based metal–organic frameworks for environmental applications: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1295–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shen, K.; Li, Y. Greening the processes of metal-organic framework synthesis and their use in sustainable catalysis. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 3165–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Nie, Y.; Tian, X.; Dai, C.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Z.X.; Wang, Y. Surface weak acid-base pair of FeOOH/Al2O3 for enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation in degradation of humic substances from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 387, 124064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Dai, C.; Tian, X.; Nie, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, Y. Effects of Lewis acid-base site and oxygen vacancy in MgAl minerals on peroxymonosulfate activation towards sulfamethoxazole degradation via radical and non-radical mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 286, 120437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, S.; Golubev, Y.A.; Lin, S.; Liu, J.; Dong, F.; Kotova, O.B. Intrinsic peroxidase-like clay mineral nanozyme-triggered cascade bioplatform with enhanced catalytic performance. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 246, 107196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.L.; Yu, G.H.; Kappler, A.; Liu, C.Q.; Gadd, G.M. Fungal-mineral interactions modulating intrinsic peroxidase-like activity of iron nanoparticles: Implications for the biogeochemical cycles of nutrient elements and attenuation of contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshatteri, A.H.; Ameen, S.S.M.; Latif, D.; Mohammad, Y.O.; Omer, K.M. Nanoscale mineral as a novel class enzyme mimic (mineralzyme) with total antioxidant capacity detection: Colorimetric and smartphone-based approaches. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 40, 102262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xue, Y.; Han, S.; Chen, W.; Fu, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X. V2O5-montmorillonite nanocomposites of peroxidase-like activity and their application in the detection of H2O2 and glutathione. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 195, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, K.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; Fu, M.; Yue, K.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Q. Glutathione detection based on peroxidase-like activity of Co3O4-Montmorillonite nanocomposites. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 2018, 273, 1635–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, F.; Vitiello, R.; Russo, V.; Tesser, R.; Turco, R.; Di Serio, M. Biodiesel production from waste oil catalysed by metal-organic framework (MOF-5): Insights on activity and mechanism. Catalysts 2023, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, T. Green synthesis of iron nanoparticles using green tea and its removal of hexavalent chromium. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, J.A.A.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Perez-Puyana, V.; Guerrero, A.; Romero, A. Green synthesis of FexOy nanoparticles with potential antioxidant properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Herranz, T.; Weis, C.; Bluhm, H.; Salmeron, M. Adsorption of water on Cu2O and Al2O3 thin films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 9668–9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftyürek, E.; Šmíd, B.; Li, Z.; Matolín, V.; Schierbaum, K. Spectroscopic understanding of SnO2 and WO3 metal oxide surfaces with advanced synchrotron based; XPS-UPS and near ambient pressure (NAP) XPS surface sensitive techniques for gas sensor applications under operational conditions. Sensors 2019, 19, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; He, S.; Xu, M.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Promoted synergic catalysis between metal Ni and acid-base sites toward oxidant-free dehydrogenation of alcohols. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2735–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Yin, A.X.; Luo, C.; Sun, L.D.; Zhang, Y.W.; Duan, W.T.; Liu, H.C.; Yan, C.H. Facile synthesis for ordered mesoporous γ-aluminas with high thermal stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3465–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Core–shell magnetic Fe3O4/CNC@MOF composites with peroxidase-like activity for colorimetric detection of phenol. Cellulose 2021, 28, 9253–9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; He, Y.; He, J.; Hou, X. Wavelength-shift-based visual fluorescence sensing of aspartic acids using Eu/Gd-MOF through pH triggering. Talanta 2023, 265, 124778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.; Zheng, T.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z. A highly selective turn-on luminescent logic gates probe based on post-synthetic MOF for aspartic acid detection. Sensors Actuat. B-Chem. 2019, 284, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.F.; Hou, S.L.; Shi, Y.; Yang, G.L.; Qin, D.B.; Zhao, B. Stable lanthanide–organic framework as a luminescent probe to detect both histidine and aspartic acid in water. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 6356–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Lu, L.; Feng, S.; Zhu, M. First Ln-MOF as a trifunctional luminescent probe for the efficient sensing of aspartic acid, Fe3+ and DMSO. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 7514–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.K.; Zhang, B.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.Y. Post-synthetic functionalization of Ni-MOF by Eu3+ ions: Luminescent probe for aspartic acid and magnetic property. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 7531–7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Qi, D.; Si, X.; Yan, Z.; Guo, L.; Shao, C.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L. One novel Cd-MOF as a highly effective multi-functional luminescent sensor for the detection of Fe3+, Hg2+, CrVI, Aspartic acid and Glutamic acid in aqueous solution. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 310, 123008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Chen, Y.; Hu, J.; Lu, G.; Zeng, L.; Choi, W.; Zhu, M. Complexes of Fe (III)-organic pollutants that directly activate Fenton-like processes under visible light. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2021, 283, 119663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kim, D.G.; Ko, S.O. Role of N-doping and O-groups in unzipped N-doped CNT Carbocatalyst for Peroxomonosulfate activation: Quantitative structure-activity relationship. Catalysts 2022, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.K.; Kumar, C.V.; Das, P.K. Laser flash photolytic determination of triplet yields via singlet oxygen generation. J. Photochem. 1984, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detty, M.R.; Merkel, P.B. Chalcogenapyrylium dyes as potential photochemotherapeutic agents. Solution studies of heavy atom effects on triplet yields, quantum efficiencies of singlet oxygen generation, rates of reaction with singlet oxygen, and emission quantum yields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 3845–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontmorin, J.M.; Castillo, R.B.; Tang, W.Z.; Sillanpää, M. Stability of 5, 5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide as a spin-trap for quantification of hydroxyl radicals in processes based on Fenton reaction. Water Res. 2016, 99, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.Y.; Huang, C.H.; Mao, L.; Shao, B.; Shao, J.; Yan, Z.Y.; Miao, T.; Zhu, B.Z. First direct and unequivocal electron spin resonance spin-trapping evidence for pH-dependent production of hydroxyl radicals from sulfate radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14046–14056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Deng, Q. Breaking binary competitive adsorption in the domino synthesis of pyrroles from furan alcohols and nitroarenes over metal phosphide. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2022, 316, 121665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifantiev, E.E.; Grachev, M.K.; Burmistrov, S.Y. Amides of trivalent phosphorus acids as phosphorylating reagents for proton-donating nucleophiles. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 3755–3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Meng, S.; Nan, Z. Singlet Oxygen Formation Mechanism for the H2O2-Based Fenton-like Reaction Catalyzed by the Carbon Nitride Homojunction. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 6701–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidheesh, P.V.; Boczkaj, G.; Ganiyu, S.O.; Oladipo, A.A.; Fedorov, K.; Xiao, R.; Dionysiou, D.D. Generation, properties, and applications of singlet oxygen for wastewater treatment: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 195–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, H.D.; Eilers, B.; Lange, A. Formation of singlet molecular oxygen by the Radziszewski reaction between acetonitrile and hydrogen peroxide in the absence and presence of ketones. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Xu, M.; Bai, Y.; Liu, T. MIL-101 (Fe)@ Ag rapid synergistic antimicrobial and biosafety evaluation of nanomaterials. Molecules 2022, 27, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.J.; Jia, J.J.; Wen, H.Y.; Li, S.Q.; Wu, Y.J.; Wang, Q.; Kan, Z.W.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, J.X.; et al. Axial optimization of biomimetic nanoenzyme catalysts applied to oxygen reduction reactions. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 3550–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanozyme | O | Fe | Al | Si | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Py-MOF | 39.3 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 44.7 |

| OH-MOF | 51.4 | 6.0 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 39.7 |

| Ka-MOF | 38.2 | 10.1 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 45.5 |

| Nanozyme | Km (mM) | Vmax (10−7 M min−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O2 | OPD | H2O2 | OPD | |

| Py-MOF | 1.2 | 0.4 | 57.0 | 17.2 |

| OH-MOF | 0.3 | 0.7 | 27.8 | 35.0 |

| Ka-MOF | 0.05 | 0.4 | 20.7 | 24.3 |

| HPR | 0.2 | 1.8 | 4.6 | 7.2 |

| Probe | Limit of Detection | Linear Range | Response Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu/Gd-MOF | 18 μM | 0–5.0 mM | 15 min | [41] |

| Cu/Tb@Zn-MOF | 4.132 μM | 20–140 μM | - 30 min | [42] |

| [Eu-(L) (H2O)2] | 10−4 M | 0–10 mM | 20 min | [43] |

| Tb-MOF | 7.95 × 10−6 M | 0–100 μM | 30 min | [44] |

| Ni (II)-MOF | 2.51 mmol/L | 0–1.136 mmol/L | 10 min | [45] |

| Cd-MOF | 2.68 × 10−6 M | 0–10 μM | 30 min | [46] |

| Ka-MOF | 55.7 nM | 0–37.46 μM | 20 min | This work |

| Sample | Spiked Concentration (μM) | Found (μM) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%, n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deionized water | 1 | 0.9747 | 97.5 | 1.8 |

| 2 | 1.952 | 97.6 | 2.4 | |

| 5 | 4.926 | 98.5 | 2.1 | |

| Pond water | 1 | 0.953 | 95.3 | 1.36 |

| 2 | 1.883 | 94.1 | 2.05 | |

| 5 | 4.820 | 96.4 | 1.82 | |

| Aquatic products | 1 | 0.9458 | 94.6 | 2.6 |

| 2 | 1.860 | 93 | 2.8 | |

| 5 | 4.752 | 95.0 | 2.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, C.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Dai, C.; Gan, J. Enhancement of the Peroxidase Activity of Metal–Organic Framework with Different Clay Minerals for Detecting Aspartic Acid. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121172

Tian C, Zhang L, Yu Y, Liu T, Chen J, Peng J, Dai C, Gan J. Enhancement of the Peroxidase Activity of Metal–Organic Framework with Different Clay Minerals for Detecting Aspartic Acid. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121172

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Chen, Lang Zhang, Yali Yu, Ting Liu, Jianwu Chen, Jie Peng, Chu Dai, and Jinhua Gan. 2025. "Enhancement of the Peroxidase Activity of Metal–Organic Framework with Different Clay Minerals for Detecting Aspartic Acid" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121172

APA StyleTian, C., Zhang, L., Yu, Y., Liu, T., Chen, J., Peng, J., Dai, C., & Gan, J. (2025). Enhancement of the Peroxidase Activity of Metal–Organic Framework with Different Clay Minerals for Detecting Aspartic Acid. Catalysts, 15(12), 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121172