1. Introduction

Trichloroethylene (TCE) is one of the most widely used chlorinated organic solvents for metal degreasing, dry-cleaning, and chemical manufacturing. Owing to its high volatility, hydrophobicity, and chemical stability, TCE persists in subsurface environments and can serve as a long-term source of groundwater contamination [

1,

2,

3]. Exposure to TCE has been associated with hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and carcinogenicity. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies TCE as a Group 1 carcinogen [

4]. Therefore, developing efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective technologies for TCE removal is of great importance for public health and environmental protection.

Nano-scale zero-valent iron (nZVI) has emerged as a promising reductive material for in situ remediation of chlorinated hydrocarbons because of its high specific surface area, strong reducing capacity, and environmental compatibility [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The Fe

0 core of nZVI donates electrons to dechlorinate TCE and other chlorinated ethenes, ultimately converting them into non-toxic hydrocarbons such as ethane and ethylene [

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, crystalline nZVI (C-nZVI) still suffers from several intrinsic drawbacks: (i) rapid oxidation rapid surface oxidation generates a passivating iron-(oxy)oxide shell that blocks access to underlying Fe

0 and impedes electron transfer, thereby decreasing reactivity; (ii) magnetic interactions and van der Waals forces promote nanoparticle aggregation, reducing the accessible reactive surface area; and (iii) side reactions such as hydrogen evolution consume electrons that would otherwise drive contaminant reduction, resulting in low electron utilization efficiency (ε

e < 10%) [

13,

14].

To address these limitations, various modification strategies have been developed, including surface coating [

15,

16,

17], bimetallic alloying [

18], sulfidation [

19,

20,

21], heteroatom doping [

22], and structural amorphization [

23]. Among these, amorphous zero-valent iron (A-nZVI) has shown particular promise. In contrast to crystalline materials with long-range atomic order, amorphous iron features short-range disorder, abundant defects, and unsaturated coordination sites that enhance electron mobility, facilitate Fe-Fe bond activation, and prevent localized passivation [

24]. Moreover, the disordered structure of A-nZVI provides more reactive sites and prolongs the material’s lifetime by inhibiting the formation of dense oxide layers [

25].

Incorporating nitrogen-containing ligands during iron synthesis offers an additional means to modulate structure and surface chemistry. Nitrogen dopants can form Fe-N coordination bonds that regulate nucleation, suppress aggregation, and stabilize amorphous phases. Ethylenediamine (EDA), a bidentate ligand with strong Fe-coordination ability, has been shown to favor the formation of Fe-N bonds and promote homogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles. Recent studies have demonstrated that nitrogen-modified or nitrogen-sulfur co-incorporated nZVI exhibits superior reactivity and selectivity in dechlorination reactions by improving electron transfer and reducing parasitic hydrogen generation [

26,

27,

28,

29]. For instance, Gong et al. synthesized N,S-co-doped ZVI that achieved nearly 2-fold higher TCE degradation rate and 47.5% greater electron efficiency than unmodified ZVI [

25]. Similarly, Brumovský et al. reported that iron-nitride nanoparticles exhibited enhanced reductive dechlorination activity due to their unique Fe-N surface coordination [

30].

Despite these advances, EDA-modified amorphous nZVI (A-nZVI) has not yet been reported for TCE degradation, to the best of our knowledge. Previous studies using EDA or related ligands have mainly focused on material synthesis/structural stabilization and applications other than TCE dechlorination [

31,

32]. As a result, how amorphization and Fe-N coordination on dechlorination kinetics, electron utilization efficiency, and product selectivity remain unclear. Moreover, most mechanistic and performance studies on TCE dechlorination have centered on crystalline or partially oxidized nZVI systems, leaving the behavior of fully amorphous nZVI in this context insufficiently understood [

33,

34].

In this study, we synthesized EDA-modified amorphous nano zero-valent iron (A-nZVI) via a liquid-phase reduction method and systematically investigated its physicochemical properties, TCE dechlorination performance, and underlying mechanism. Morphology, crystallinity, and surface composition were characterized by SEM, XRD, and XPS, and electrochemical measurements were used to probe redox behavior and electron transfer kinetics. Batch experiments quantified TCE degradation, product distribution, hydrogen evolution, and electron utilization efficiency, with crystalline nZVI as a benchmark. Finally, kinetic modeling and mechanistic analysis were performed to elucidate the multi-stage dechlorination process and clarify the role of Fe–N coordination in enhancing electron selectivity. These findings provide guidance for designing amorphous Fe-based nanomaterials for efficient and selective dechlorination of chlorinated solvents in groundwater remediation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physical Characterization

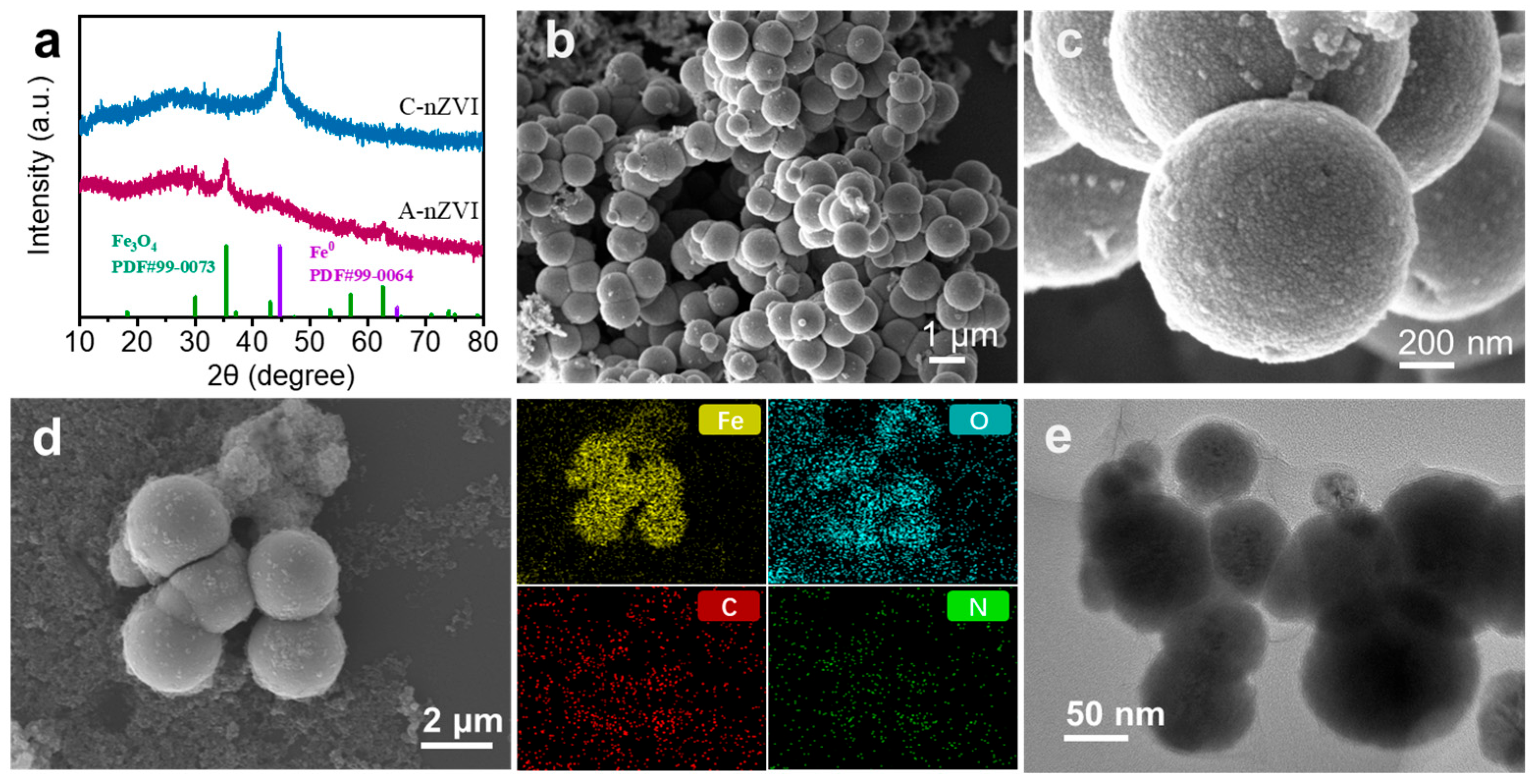

The XRD patterns of A-nZVI and C-nZVI (

Figure 1a) further highlight their structural differences. C-nZVI shows a sharp diffraction peak at 2θ = 44.6°, which can be indexed to the Fe

0(110) plane (PDF#99-0064), characteristic of crystalline α-Fe. In contrast, A-nZVI showed no detectable Fe

0 diffraction peaks, indicating the absence of long-range crystallographic order. A weak reflection at 2θ = 35.4° is observed and assigned to Fe

3O

4(311) (PDF#99-0073), suggesting the presence of a thin surface oxide layer formed during sample drying and exposure to air.

The morphology and elemental distribution of A-nZVI were characterized by SEM coupled with EDS (

Figure 1b–d). As shown in

Figure 1b, A-nZVI forms cauliflower-like, spherical aggregates with a rough surface and without well-defined crystalline facets, consistent with a largely amorphous/poorly crystalline structure. Higher-magnification SEM image (

Figure 1c) shows that these aggregates are built from nearly spherical primary nanoparticles (~20–50 nm), which assemble into secondary agglomerates of ~500–1000 nm, likely driven by high surface energy and magnetic interactions. The rough, textured surface can increase the density of accessible reactive sites and facilitate mass/electron transfer, although it may also be more susceptible to surface oxidation [

35]. EDS elemental mapping (

Figure 1d) reveals Fe and O as the dominant elements and shows that C and N signals are broadly co-distributed across the particles, supporting successful EDA modification. The presence of uniformly distributed N is consistent with Fe–N coordination and/or surface-bound EDA species, which can inhibit directional crystal growth and alleviate severe aggregation during particle formation. To directly resolve the primary nanoparticles, TEM was further employed. Because nZVI is strongly magnetic, large agglomerates can dominate drop-cast specimens and appear as dense, featureless masses under TEM, preventing reliable size determination. Therefore, prior to TEM imaging we briefly removed the largest magnetic agglomerates by magnetic separation. With this standardized preparation step, the TEM image (

Figure 1e) clearly shows primary particles predominantly in the 20–50 nm range, consistent with the SEM observations and our size description. Consistently, BET analysis from N

2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (

Figure S1) shows that A-nZVI possesses a much higher specific surface area (42.21 m

2 g

−1) than C-nZVI (9.02 m

2 g

−1), which is expected to increase the density of accessible surface sites and benefit interfacial reactions.

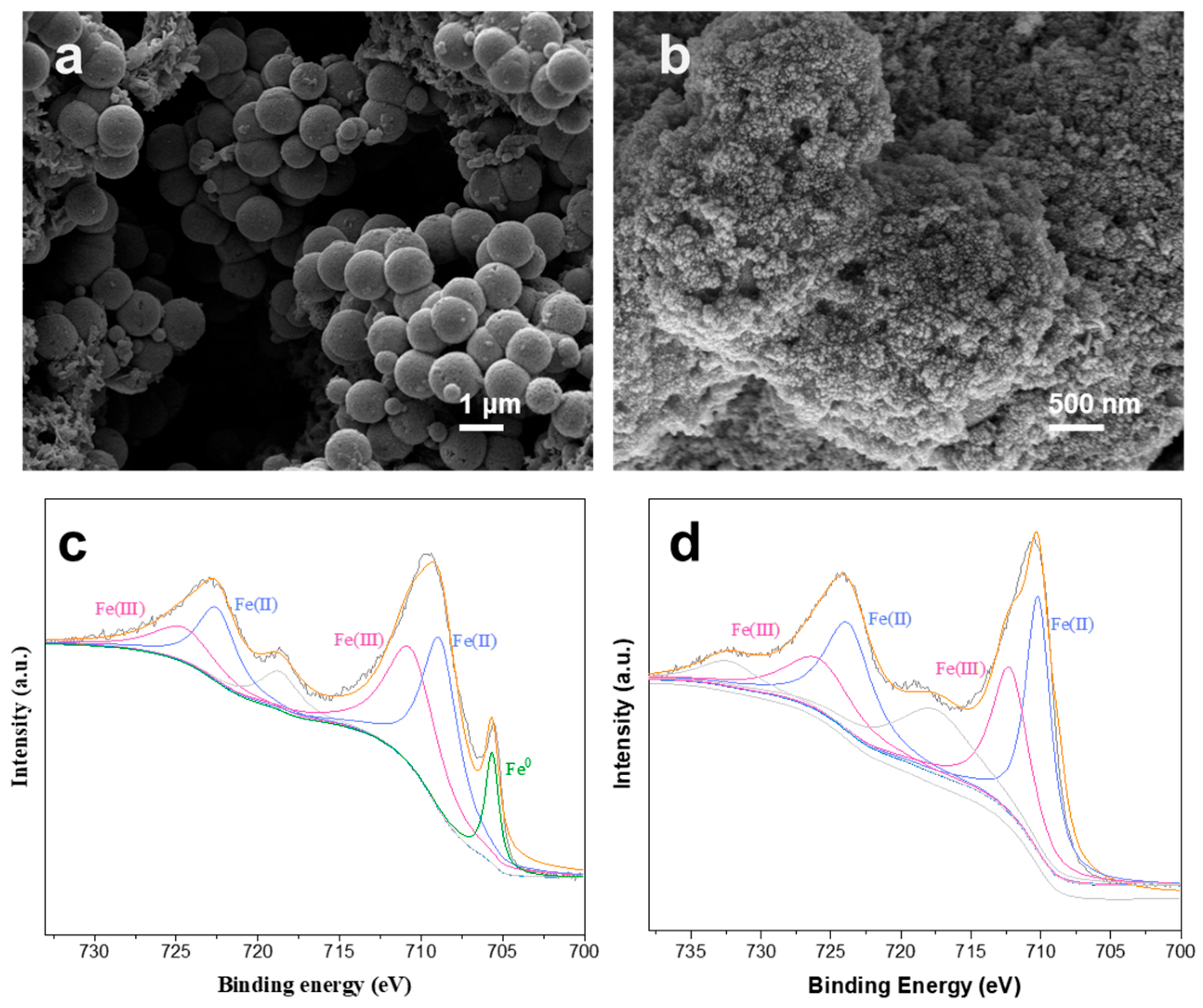

XPS analysis (

Figure 2) provided detailed information on the surface chemical composition and oxidation states of A-nZVI. The survey spectrum (

Figure 2a) confirmed the presence of Fe, O, C, and N, consistent with EDS results. In the Fe 2p spectrum (

Figure 2b), the main peaks at 709.6 eV and 723.4 eV, together with satellite features at 718.6 eV and 732.4 eV, are characteristic of oxidized iron species (Fe

2+/Fe

3+). The Fe

0 signal at 706.9 eV was relatively weak, indicating surface oxidation. The C 1s spectrum (

Figure 2c) can be deconvoluted into contributions from C–C (285.4 eV), C–N (284.5 eV), and C=O (288.5 eV). The C=O signal may originate from carbamate-like species formed via reactions between EDA and CO

2. The N 1s spectrum (

Figure 2d) shows nitrogen species associated with EDA, consistent with N incorporation and possible Fe–N coordination at the surface. These N-containing species may facilitate electron transport and promote interfacial electron transfer.

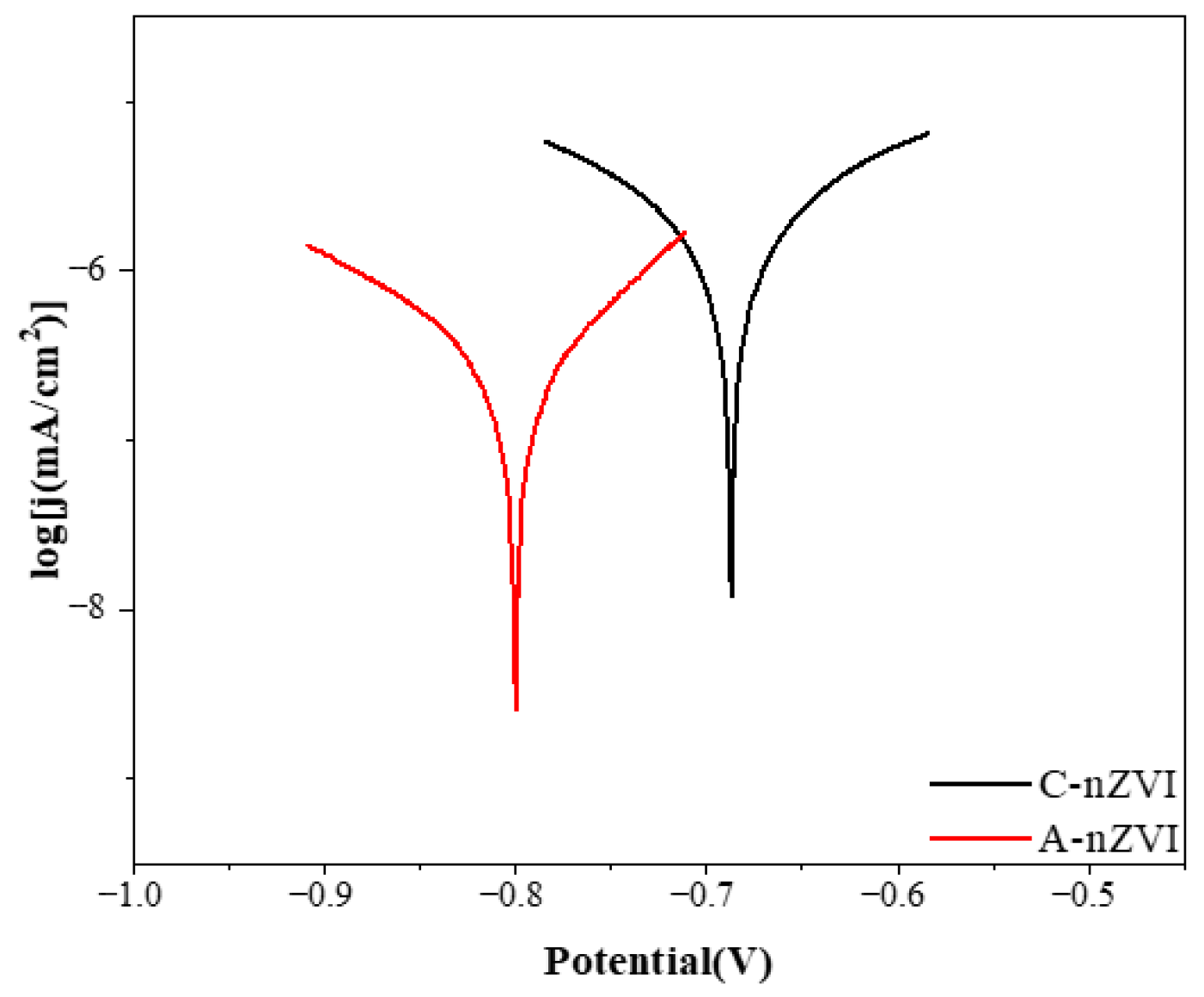

Electrochemical measurements (

Figure 3) further compared the reducing properties of A-nZVI and C-nZVI. The corrosion potential (E

corr) of A-nZVI (−0.80 V) is more negative than that of C-nZVI (−0.68 V), indicating a greater thermodynamic driving force for electron donation. The spherical agglomerates of A-nZVI, assembled from nanosized primary particles, can provide abundant interparticle voids and transport pathways that facilitate interfacial mass transfer and charge transport. By contrast, C-nZVI with a more ordered crystalline structure typically exposes fewer defect-rich, high-energy sites and therefore shows lower electrochemical reactivity. In amorphous iron, the lack of long-range order creates abundant defects and undercoordinated sites that act as reactive centers and can promote interfacial electron transfer. As a result, A-nZVI exhibits higher electrochemical activity than its crystalline counterpart.

Overall, the combined SEM, XRD, XPS, and electrochemical analyses results support the successful synthesis of EDA-modified amorphous zero-valent iron. The material features an agglomerated, hierarchical morphology with predominantly amorphous Fe0 core and a minor surface iron-oxide component (e.g., Fe3O4). Nitrogen species introduced by EDA are associated with the iron surface (consistent with Fe–N interactions), which can improve colloidal stability and facilitate charge transport, while the amorphous structure contributes to enhanced reactivity and improved dechlorination performance.

2.2. TCE Removal Performance and Kinetic Analysis

2.2.1. Reaction Profiles and Rate Comparison

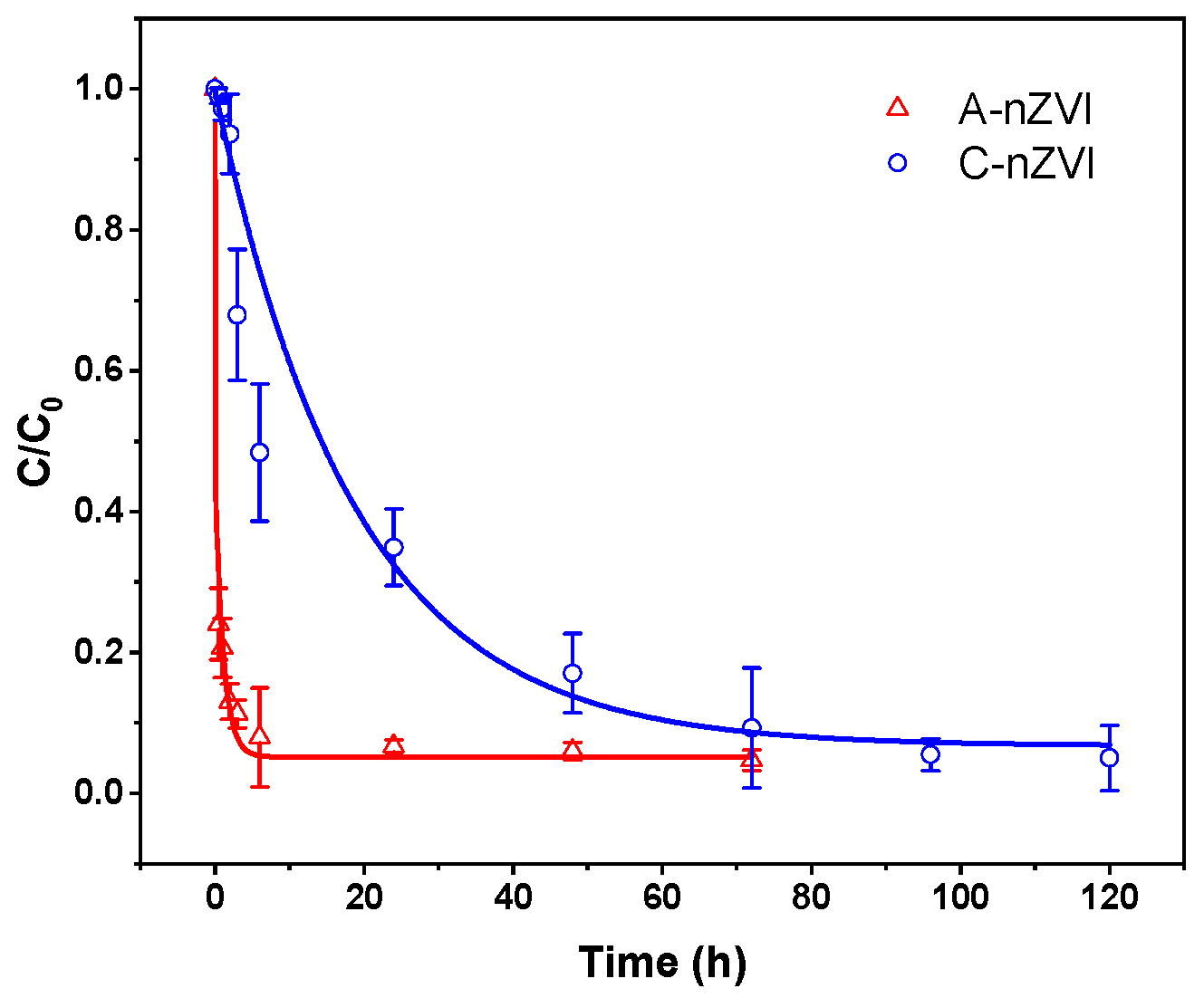

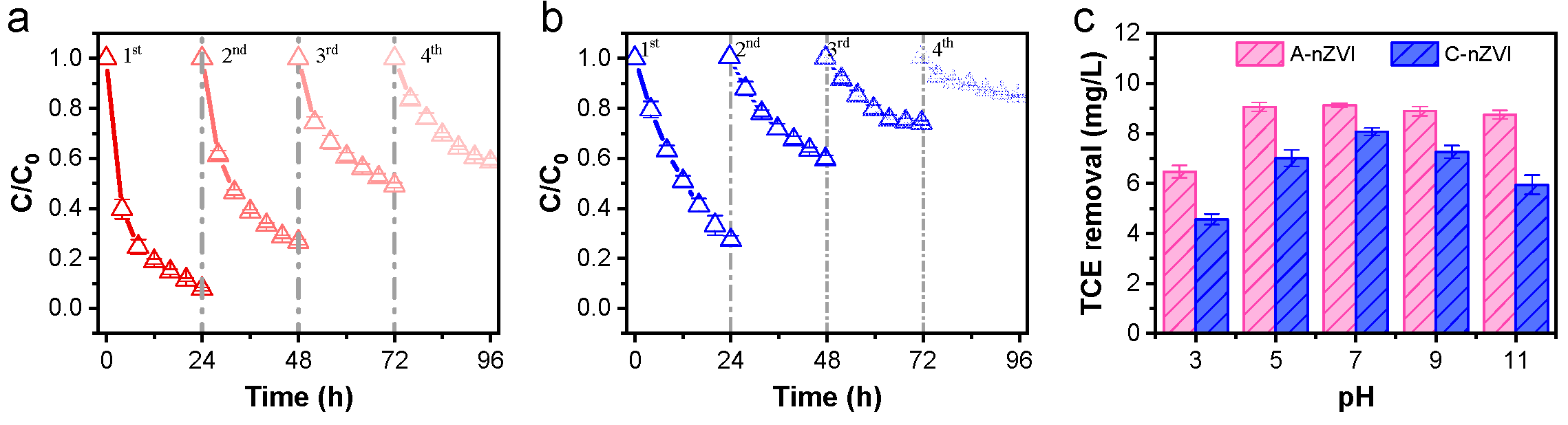

The degradation kinetics of trichloroethylene (TCE) by ethylenediamine-modified nanoscale zero-valent iron (A-nZVI) and conventional nZVI (C-nZVI) were systematically investigated to elucidate the rate-controlling mechanisms and the influence of surface coordination on reaction kinetics. As illustrated in

Figure 4, A-nZVI removed TCE significantly faster than C-nZVI. More than 50% of TCE was eliminated within the first hour, reaching near-complete removal (>98%) within 72 h, whereas C-nZVI achieved only about ~50% removal at 3 h and 95% at 120 h. During the early reaction stage (0–3 h), the degradation efficiency of A-nZVI was 1.64 times that of C-nZVI, revealing enhanced initial reactivity.

This difference arises primarily from the structural and electronic characteristics of A-nZVI. Ethylenediamine (EDA) chelation during synthesis suppressed the directional growth of Fe

2+ nuclei and yielded nanoparticles with a disordered atomic arrangement. The high density of defects and undercoordinated Fe sites served as reactive centers, lowering the activation barrier for electron transfer from Fe

0 to TCE. In addition, A-nZVI formed secondary agglomerates (~500–1000 nm) composed of 20–50 nm primary particles, resulting in a hierarchical porous structure that enhanced the diffusion and adsorption of hydrophobic TCE molecules. The coupled adsorption-reduction enabled rapid depletion of aqueous TCE in the initial stage, while the more compact and passivated structure of C-nZVI limited mass transfer and slowed the reaction [

36].

2.2.2. Kinetic Modeling and Fitting

To quantify the kinetics of TCE removal, the concentration–time profiles were fitted using pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models. For C-nZVI, the data were well described by a PFO expression [

37,

38]:

where

C0 is the initial TCE concentration,

Ct is the TCE concentration at time

t and

kobs is the apparent rate constant. The corresponding half-life is:

The fitted parameters are summarized in

Table 1. For C-nZVI,

kobs,

TCE = 0.291 h

−1 with R

2 = 0.985, giving a half-life

t1/2 = 2.38 h. This relatively low apparent rate indicates that removal is progressively influenced by transport limitations and surface passivation.

In contrast, A-nZVI exhibited a pronounced biphasic concentration–time profile that could not be adequately captured by a single PFO model. The kinetics were better described by a two-process PFO superposition using a bi-exponential decay function (ExpDec2):

where

x is time,

y is the normalized concentration (

y = C

t/C

0),

A1 and

A2 are the amplitudes of the fast and slow decay components, t

1 and t

2 are the corresponding time constants, and

y0 is the offset that accounts for a residual fraction that decays very slowly within the observation window. The derived apparent first-order rate constants are k

1 = 1/

t1 and k

2 = 1/

t2.

As summarized in

Table 1, the two-phase exponential decay model (Origin ExpDec2) provides a substantially improved description compared with a single PFO fit, supporting the presence of distinct kinetic phases during A-nZVI-mediated TCE removal. Specifically, the ExpDec2 fitting yields two characteristic time constants,

t1 = 0.00837 h and

t2 = 1.1172 h, with an overall fit quality of R

2 = 0.987. These two time constants correspond to a fast and a slow apparent first-order component (k

1 = 1/

t1, k

2 = 1/

t2), indicating a rapid initial decay within the first sampling interval followed by a slower decay that dominates at longer reaction times.

Mechanistically, the two-phase PFO behavior captured by the ExpDec2 model reflects a shift from a fast, surface-accessible regime to a slower, transport- and surface-evolution-limited regime. The remarkable disparity in apparent kinetics between the two materials can be attributed to several interrelated physicochemical factors that collectively enhance the reactivity of A-nZVI. Foremost among these are the higher specific surface area [

39,

40] and porosity [

41]. The hierarchical architecture of A-nZVI increases the accessible surface area, enabling rapid enrichment of TCE near reactive Fe

0 domains, while the micro- and mesoporous network mitigates diffusion resistance and facilitates reactant transport. This structural advantage is complemented by defect-induced electronic activation. Lattice distortion and undercoordinated Fe sites can act as highly active centers, lowering the barrier for Fe

0 oxidation and thereby accelerating interfacial electron transfer to TCE molecules. Fe–N coordination further enhances this process. The Fe–N bonding introduced by EDA not only stabilizes Fe

0 against bulk oxidation but can also provide a favorable electronic pathway that promotes charge transfer across the iron-(oxyhydr)oxide/solution interface and directs more electrons toward dechlorination rather than parasitic hydrogen evolution [

42,

43]. As the reaction proceeds, dynamic surface transformation plays a pivotal role in driving the kinetic transition embodied by the slow exponential component. Direct interfacial electron transfer and rapid consumption of TCE dominate the early period when reactive sites are abundant. With time, progressive oxidation produces Fe(OH)

2/Fe

3O

4 (oxyhydr)oxide shells that increasingly restrict electron flux and mass transport [

36,

44,

45]. Under these conditions, TCE removal becomes governed by slower interfacial processes, including diffusion through the evolving surface layer and hydrogen-assisted steps mediated by surface-bound atomic hydrogen (H*). Accordingly, the ExpDec2 fit resolves a fast decay component associated with readily accessible reactive domains and a slow component associated with late-stage limitations arising from site depletion and surface passivation.

Overall, the biphasic kinetics of A-nZVI indicate a transition in the dominant rate-limiting process during TCE removal. In the initial regime, rapid interfacial contact and efficient electron delivery enable accelerated decay, whereas in the subsequent regime the build-up of an iron (oxyhydr)oxide layer and depletion of accessible Fe

0 impose increasing transport and charge-transfer resistances, leading to a much smaller apparent decay rate. This behavior highlights the kinetic advantages of A-nZVI. Its porous, hierarchical structure promotes rapid interfacial access, while Fe–N interactions and a defect-rich framework facilitate electron transfer. Consistent with these features, the characteristic time scale of the fast component is substantially shortened relative to C-nZVI, and the overall electron utilization efficiency is markedly improved. Taken together, the two-phase PFO model provides a quantitative description of the rapid and slow regimes and offers mechanistic guidance for designing more efficient and selective reductive materials for chlorinated-solvent remediation [

26,

37].

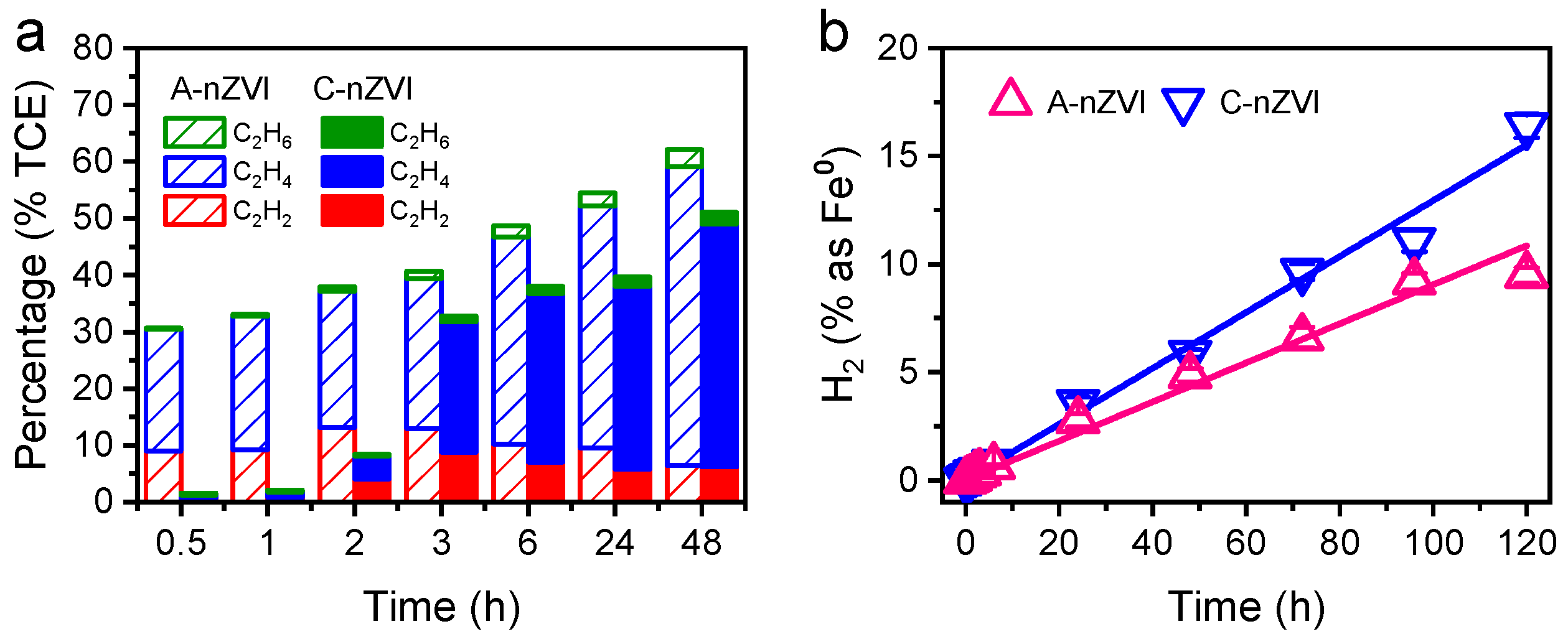

2.3. Product Analysis of TCE Dechlorination

The analysis of TCE dechlorination products provides crucial insight into the reaction mechanisms and electron transfer selectivity of A-nZVI compared with C-nZVI. The temporal evolution of degradation products (

Figure 5a) reveals that the distribution of gaseous species strongly depends on the reducing power and surface chemistry of the materials. No intermediates such as vinyl chloride (VC) and cis-1,2-dichloroethylene (cis-DCE) were detected during the entire process.

Both A-nZVI and C-nZVI produced acetylene within the first 3 h, indicating that the initial reduction in TCE was dominated by an electron-mediated β-elimination pathway. Acetylene formation suggests the simultaneous removal of two chlorine atoms from adjacent carbon atoms, generating a C≡C bond intermediate. Notably, A-nZVI yielded a substantially higher amount of C2H2 than C-nZVI, consistent with enhanced electron transfer promoted by EDA-associated Fe–N interactions. As the reaction proceeded, C2H2 decreased while C2H4 and C2H6 increased, indicating sequential hydrogenation in which acetylene is progressively converted to ethylene and ethane by atomic hydrogen generated on the iron surface. After 48 h, ethylene accounted for approximately 76.7% of the total hydrocarbon products, making it the dominant terminal product in the A-nZVI system.

To further evaluate whether chlorinated organic intermediates accumulate during TCE transformation, a chlorine mass-balance analysis was performed based on inorganic chloride (Cl

−) quantified by ion chromatography (IC) (

Table S1). The theoretical chloride release was calculated assuming complete dechlorination (3 mol Cl

− per mol TCE removed). The aqueous Cl

− concentration increased monotonically with reaction time but could be slightly below the theoretical line at early/intermediate times, which is consistent with partial chloride retention/immobilization on iron corrosion products. To obtain a closed chlorine balance, we therefore quantified total inorganic chloride at the reaction endpoint (72 h) by summing aqueous Cl

− and solid-bound Cl

− released via an acid digestion/complexation extraction protocol. The resulting molar ratio of released Cl

− to removed TCE reached ~2.96, close to the theoretical value of 3.0, indicating near-complete conversion of organochlorine to inorganic chloride and providing no evidence for the accumulation of chlorinated intermediates (e.g., DCE/VC) in the final effluent.

2.4. Hydrogen Evolution and Electron Utilization Efficiency

Hydrogen evolution is an inherent competing reaction during Fe

0 corrosion that diverts electrons from pollutant reduction to proton reduction, thereby lowering overall electron utilization efficiency [

46,

47,

48,

49]. The hydrogen generation profiles (

Figure 5b) show that the cumulative H

2 yield in the A-nZVI system was significantly lower—approximately 0.68 times that of C-nZVI—over five days. Quantitative analysis further indicated that 9.48% of Fe

0 participated in H

2 evolution for A-nZVI, compared with 16.41% for C-nZVI. The suppressed parasitic H

2 evolution in A-nZVI therefore reflects a preferential electron allocation (i.e., electron selectivity) toward TCE dechlorination rather than the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER).

The improved selectivity of A-nZVI is attributed to Fe–N interactions at the EDA-modified surface, which can stabilize reactive Fe0 and promote electron transfer to adsorbed TCE, thereby suppressing the hydrogen-evolution side reaction. XPS shows a persistent N 1s signal at ~398.5 eV, consistent with nitrogen species associated with EDA remaining on the A-nZVI surface during reaction. These N-containing surface species can modulate the local electronic structure and facilitate interfacial charge transfer, directing more electrons to dechlorination rather than water reduction.

Electron utilization efficiency (

εe) is defined as the fraction of electrons derived from Fe

0 oxidation that are consumed in pollutant reduction and was calculated using Equation (4):

where

ni denotes the number of electrons required to produce one mole of product

i,

pi is the molar yield of product

i, and

is the moles of hydrogen evolved. The stoichiometric electron requirements used in the calculation are 8 electrons for C

2H

6, 6 electrons for C

2H

4, and 4 electrons for C

2H

2. Based on product distributions and hydrogen yields,

εe values were 15.32% for A-nZVI and 8.47% for C-nZVI. This near two-fold increase in

εe demonstrates that a substantially larger fraction of electrons was utilized for TCE reduction rather than being consumed by hydrogen evolution, highlighting electron efficiency and electron selectivity toward dechlorination (vs. HER) as key factors governing the overall dechlorination performance.

2.5. Mechanistic Interpretation and Proposed Two-Stage Model

2.5.1. Surface Evolution and Chemical States During Reaction

Figure 6 shows concurrent morphological and chemical-state changes in A-nZVI during TCE dechlorination. The pristine material (

Figure 6a) consists predominantly of densely packed, quasi-spherical secondary particles on the submicron-to-micron scale (hundreds of nanometers to ~1 μm), with relatively smooth surfaces. After reaction (

Figure 6b), the discrete spherical features become largely obscured and are replaced by irregular, roughened agglomerates with a granular texture, suggesting extensive surface coverage by corrosion products and enhanced particle aggregation during reaction. Consistently, the Fe 2p

3/2 (

Figure 6c,d) show a diminished Fe

0 contribution accompanied by strengthened Fe(II)/Fe(III) features after reaction, confirming progressive oxidation of surface Fe

0 to Fe

2+ species. In addition, the N 1s signal at ~398.5 eV remains detectable after reaction, indicating that EDA-derived nitrogen species persist on the surface and that Fe–N interactions are maintained during dechlorination.

2.5.2. Integrating Kinetics, Products, and Electron Allocation: Structure–Activity Correlation

As summarized in

Table 1, A-nZVI shows a clear two-regime behavior, with a rapid initial stage followed by a markedly slower stage. Rather than reiterating the fitted parameters, this biphasic trend is attributed to progressive depletion of accessible Fe

0 sites and growth of an iron (oxyhydr)oxide surface layer, which increasingly constrains mass transport and interfacial electron transfer as the reaction proceeds. In contrast, C-nZVI is adequately described by a single apparent rate constant over the tested period, suggesting a comparatively less pronounced shift in the dominant rate-limiting step.

The kinetic advantage of A-nZVI is accompanied by improved electron selectivity. The cumulative H

2 yield is 32% lower than that of C-nZVI (

Figure 5b), indicating suppression of parasitic electron consumption. Consistently, the electron utilization efficiency (εe, Equation (4)) increases from 8.47% (C-nZVI) to 15.32% (A-nZVI). Together, these results indicate that EDA-associated Fe–N interactions and the defect-rich amorphous framework not only accelerate the initial interfacial reaction but also suppress the competing hydrogen-evolution pathway, thereby directing a larger fraction of electrons toward TCE dechlorination.

2.5.3. Proposed Two-Stage Fe–N-Regulated Mechanism and Practical Implications

Based on the kinetic transition (

Table 1), product analysis, and the electrochemical trends discussed above (

Figure 3), a two-stage Fe–N-regulated dechlorination mechanism is proposed (

Figure 7):

Stage I (0–3 h): Direct β-elimination dominated by interfacial electron transfer at Fe–N-associated sites. TCE is rapidly adsorbed and reduced, which can be represented by Equation (5):

Stage II (3–72 h): Sequential hydrogenation mediated by surface-bound atomic hydrogen (H*), which is generated via water/proton reduction on the iron surface (Equation (6)),

and subsequently consumed in hydrogenation (Equations (7) and (8)):

Across both stages, Fe–N interactions are proposed to facilitate interfacial charge transfer and improve electron selectivity, which helps sustain dechlorination while suppressing competing hydrogen evolution.

In the C-nZVI system, slower interfacial electron transfer and weaker surface electronic modulation favor more extensive water reduction, resulting in higher H

2 evolution and lower ε

e [

16]. Consequently, fewer electrons are available for C–Cl bond cleavage, which reduces overall efficiency and selectivity [

48,

50]. The higher ε

e (15.32%) obtained for A-nZVI indicates that a larger fraction of electrons is directed to TCE dechlorination rather than wasted in side reactions, supporting the role of Fe–N interactions in improving electron allocation.

From an engineering viewpoint, A-nZVI shows sustained reactivity over four reuse cycles, retaining ~40% activity after the fourth run (

Figure 8a,b). In addition, stable performance across pH 5–7 (

Figure 8c) suggests tolerance to typical groundwater conditions. These attributes support the potential of Fe–N coordination as a viable strategy for developing iron-based reductive materials with improved electron utilization and minimized side reactions in chlorinated-solvent remediation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O, ≥99%) and ethylenediamine (EDA, ≥99%) were obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Sodium borohydride (NaBH4, ≥98%) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥99%) were purchased from Tianjin Bohua Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Absolute ethanol (≥99.7%) and trichloroethylene (TCE, ≥99.9%) were supplied by Tianjin Concord Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). High-purity N2 (99.999%) and Ar (99.999%) were purchased from Tianjin Best Gas Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China), and a mixed H2/N2 gas (30% H2, balance N2) was obtained from Tianjin Taiya Gas Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Standard gas mixtures (3000 mg/L ethane, ethene, and acetylene in Ar) were also supplied by Taiya. Deionized water (≥18.2 MΩ·cm) was deoxygenated by purging with N2 for 25 min before use.

3.2. Synthesis of C-nZVI and A-nZVI

3.2.1. Synthesis of Crystalline nZVI (C-nZVI)

C-nZVI was prepared by liquid-phase reduction. Deoxygenated water (250 mL) was placed in a three-neck flask and maintained under an N2 atmosphere. FeSO4·7H2O (0.10 mol/L) was dissolved under stirring (500 rpm). A reducing solution containing NaBH4 (0.30 mol/L) and NaOH (0.02 g) in 50 mL water was added dropwise (≈2 drops/s) under vigorous agitation (1000 rpm). The reaction proceeded for 30 min under N2. The black precipitate was magnetically separated, washed three times with deoxygenated water and ethanol, and dried under N2 to obtain C-nZVI.

3.2.2. Synthesis of Amorphous nZVI (A-nZVI)

A-nZVI was synthesized using the same procedure, with EDA introduced as a structure-modifying agent. Deoxygenated water (190 mL) was mixed with 60 mL EDA solution (0.9 mol/L) under N2. After adding FeSO4·7H2O (0.10 mol/L), the same NaBH4–NaOH reducing solution was introduced dropwise at 1000 rpm for 30 min under N2. The obtained black particles were washed and dried as described above to obtain A-nZVI-0.9. Samples prepared with 0.3, 0.6, and 1.2 mol/L EDA were denoted A-nZVI-0.3, A-nZVI-0.6, and A-nZVI-1.2, respectively.

3.3. TCE Dechlorination Experiments

Batch dechlorination experiments were conducted in 120 mL serum bottles containing 50 mL deoxygenated water and 0.26 g material (5.2 g/L). Bottles were sealed with Teflon-lined Mininert valves, purged with N

2, and spiked with TCE to an initial concentration of 10 mg/L. The bottles were shaken at 200 rpm and 25 ± 0.5 °C. Headspace samples (100 μL) were periodically collected and analyzed by GC/FID (Agilent 6820A) for TCE and non-chlorinated hydrocarbon products (C

2H

2, C

2H

4, and C

2H

6). Hydrogen was quantified by GC/TCD (Agilent 6820B). Calibration curves showed R

2 ≥ 0.999 using certified standards (

Figure S2).

To identify the optimal EDA dosage, A-nZVI prepared with different EDA concentrations was compared for TCE dechlorination performance. Among the tested concentrations, 0.9 M EDA delivered the best performance (

Figure S3). Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent experiments were conducted using A-nZVI synthesized with 0.9 M EDA (A-nZVI-0.9).

To evaluate the effect of initial pH, the pH was adjusted to 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0, and 11.0 using HNO3 and NaOH. For these tests, the material dosage was 1 g/L and the initial TCE concentration was 10 mg/L. Bottles were shaken at 300 rpm and 25 °C for 24 h. Headspace gas (250 μL) was collected using a gas-tight syringe and analyzed by GC/FID to determine residual TCE.

Chloride release was therefore quantified by ion chromatography (IC), and the measured Cl− concentrations were used to evaluate the chloride mass balance relative to TCE removal. To avoid underestimation caused by chloride retention on reacted iron solids, the spent iron was digested prior to IC analysis to release associated chloride. Three controls were included: an abiotic blank, a material blank, and a poisoned control (0.02% HgCl2). All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

3.4. Characterization

Morphology was examined by SEM (TESCAN MIRA LMS, 3 kV) after ultrasonically dispersing samples in ethanol and drying them on copper grids. Crystallinity was determined by XRD (Rigaku SmartLab-SE, Cu Kα, λ = 1.5406 Å, 10–80°, 5°/min). Surface composition and Fe oxidation states were analyzed by XPS (Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi) with C 1s = 284.8 eV for charge correction. Electrochemical properties were measured using a Corrtest CS350H workstation with a three-electrode configuration (working electrode: Fe sample, counter electrode: Pt, reference electrode: Ag/AgCl). Potentiodynamic polarization curves were recorded at 0.5 mV/s to evaluate corrosion potential and charge-transfer behavior.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this work elucidates the structure–reactivity relationship and dechlorination pathway of trichloroethylene (TCE) over ethylenediamine-modified nanoscale zero-valent iron (A-nZVI), highlighting the role of Fe–N interfacial interactions in improving electron selectivity and suppressing competing reactions. EDA modification produced a defect-rich amorphous iron phase with EDA-associated nitrogen species at the surface, which enhances accessible reactive sites and mitigates aggregation and passivation relative to conventional nZVI. TCE removal over A-nZVI followed a two-stage kinetic behavior, with a rapid initial phase (PSO) and a slower phase (PFO). Only non-chlorinated hydrocarbons (C2H2, C2H4, and C2H6) were detected, and no chlorinated intermediates (e.g., DCE or VC) were observed under the present analytical conditions. Electron balance analysis showed an electron utilization efficiency (εe) of 15.32% for A-nZVI (≈81% higher than C-nZVI) and a 32% reduction in H2 evolution, indicating more selective electron allocation toward C–Cl bond cleavage. A-nZVI also retained ~40% activity after four cycles and maintained good performance across pH 6–11, supporting its potential for groundwater remediation. Overall, Fe–N coordination offers a practical strategy to enhance the efficiency and stability of Fe-based reductive materials for chlorinated-solvent remediation.