Glucose-Mediated Synthesis of Spherical Carbon Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles as Catalyst in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

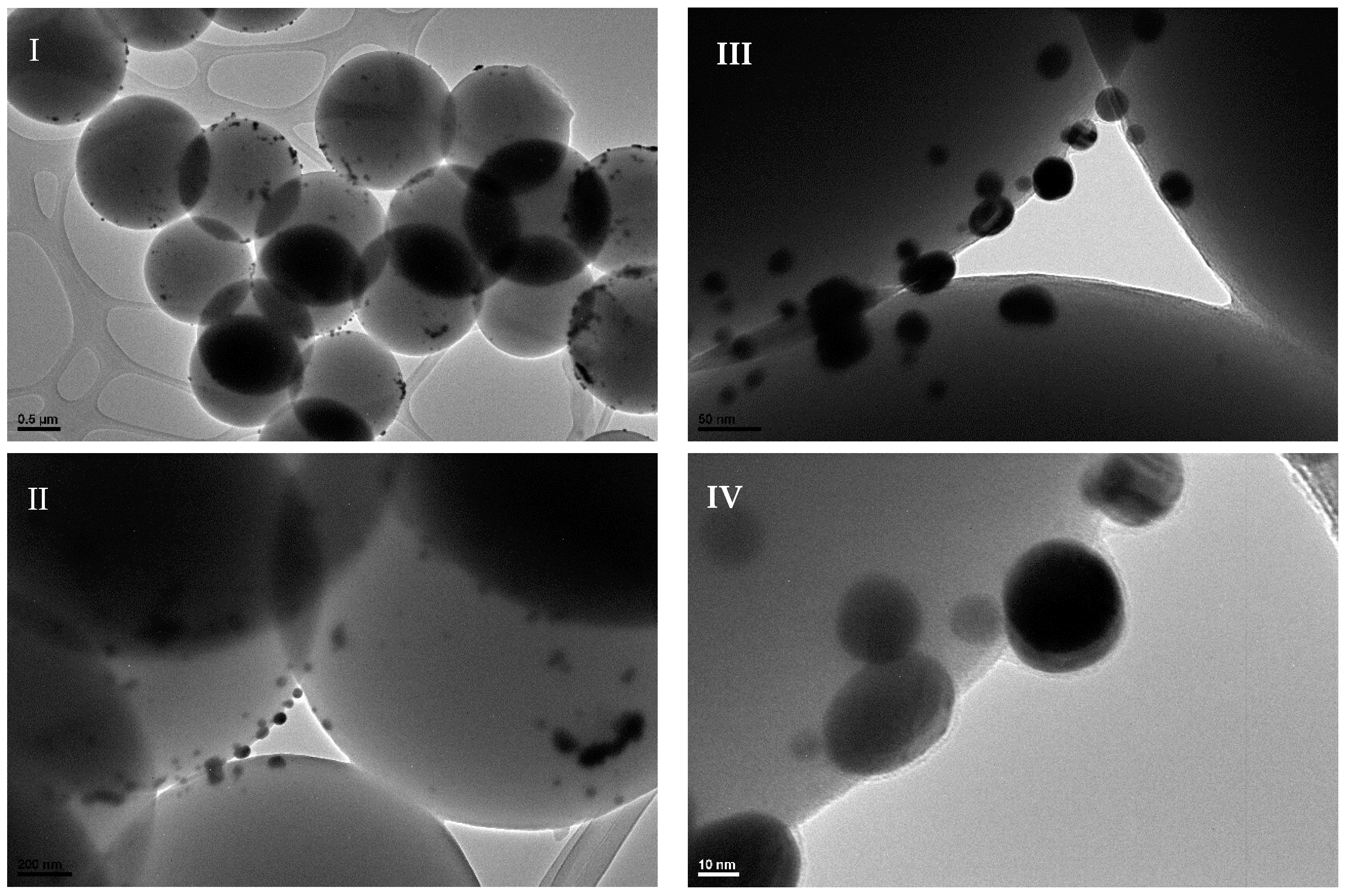

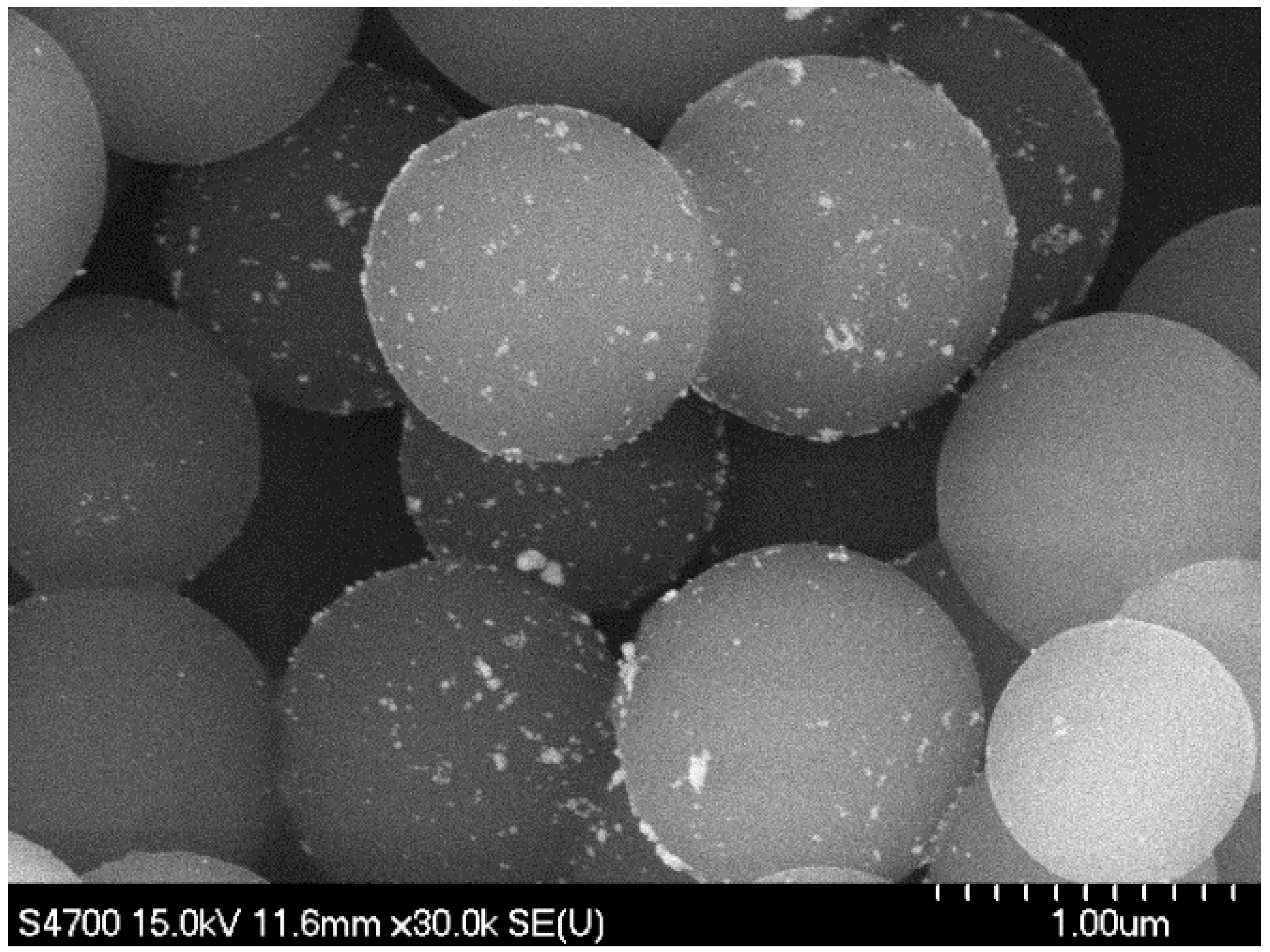

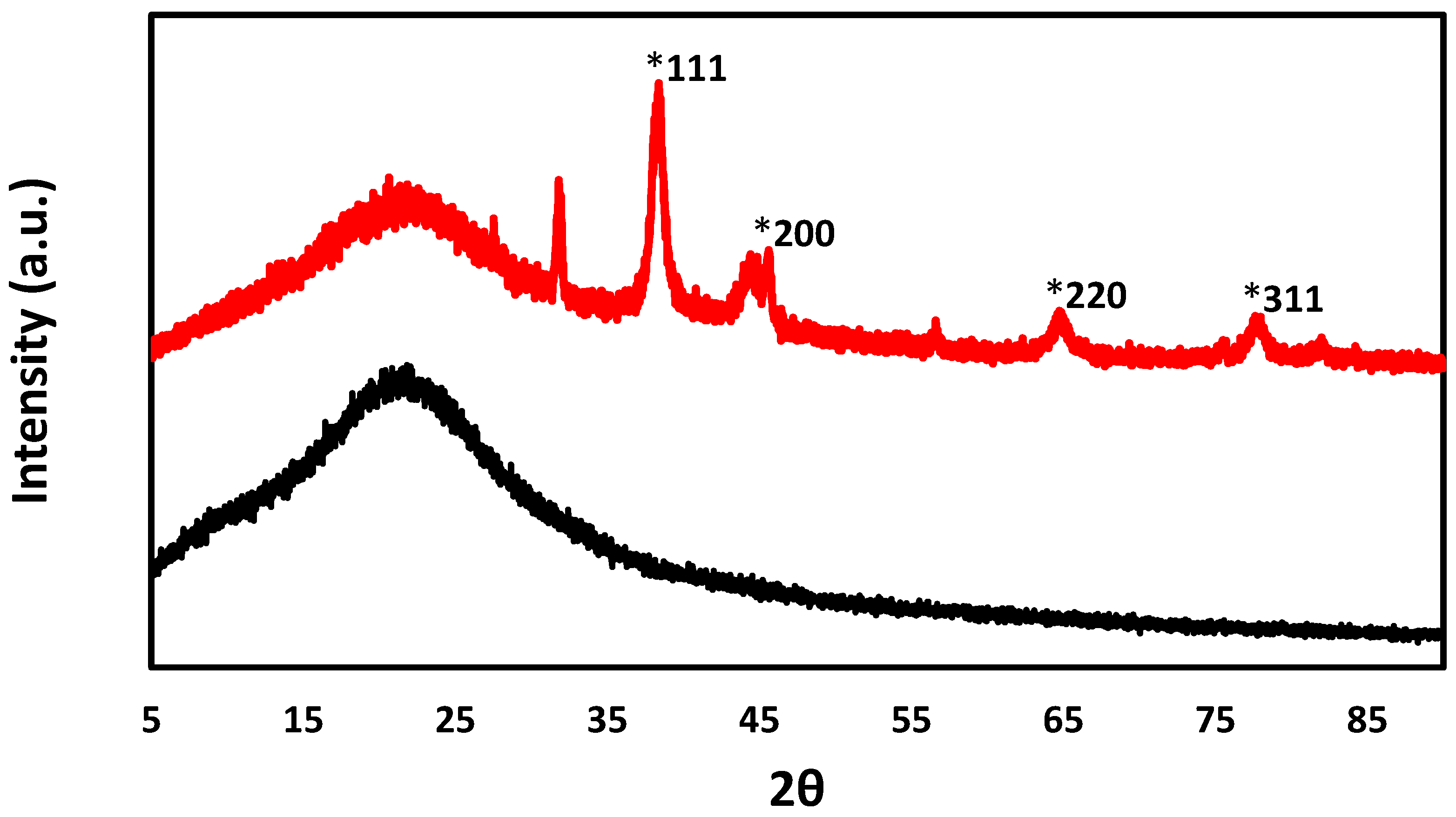

2.1. Catalyst Characterization

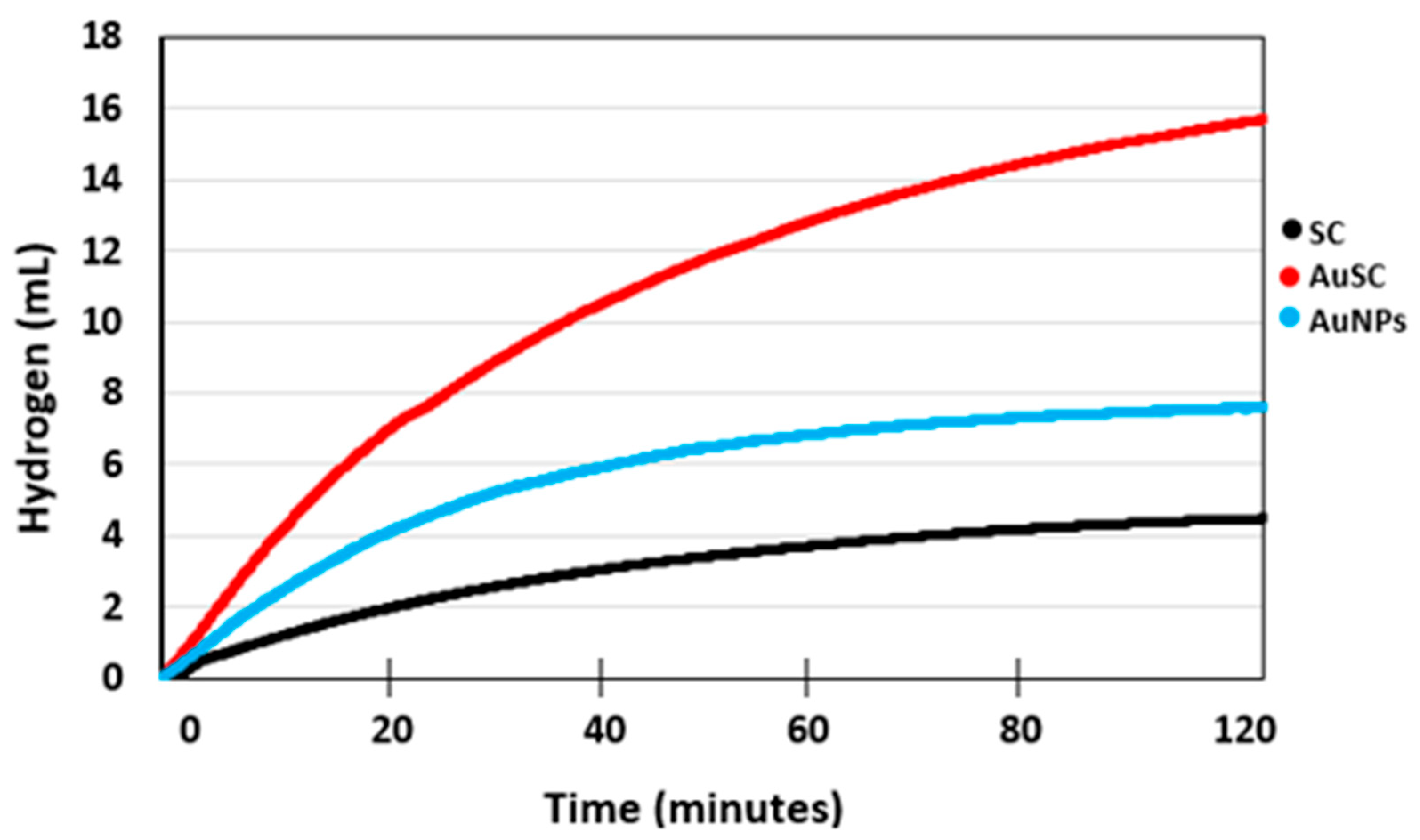

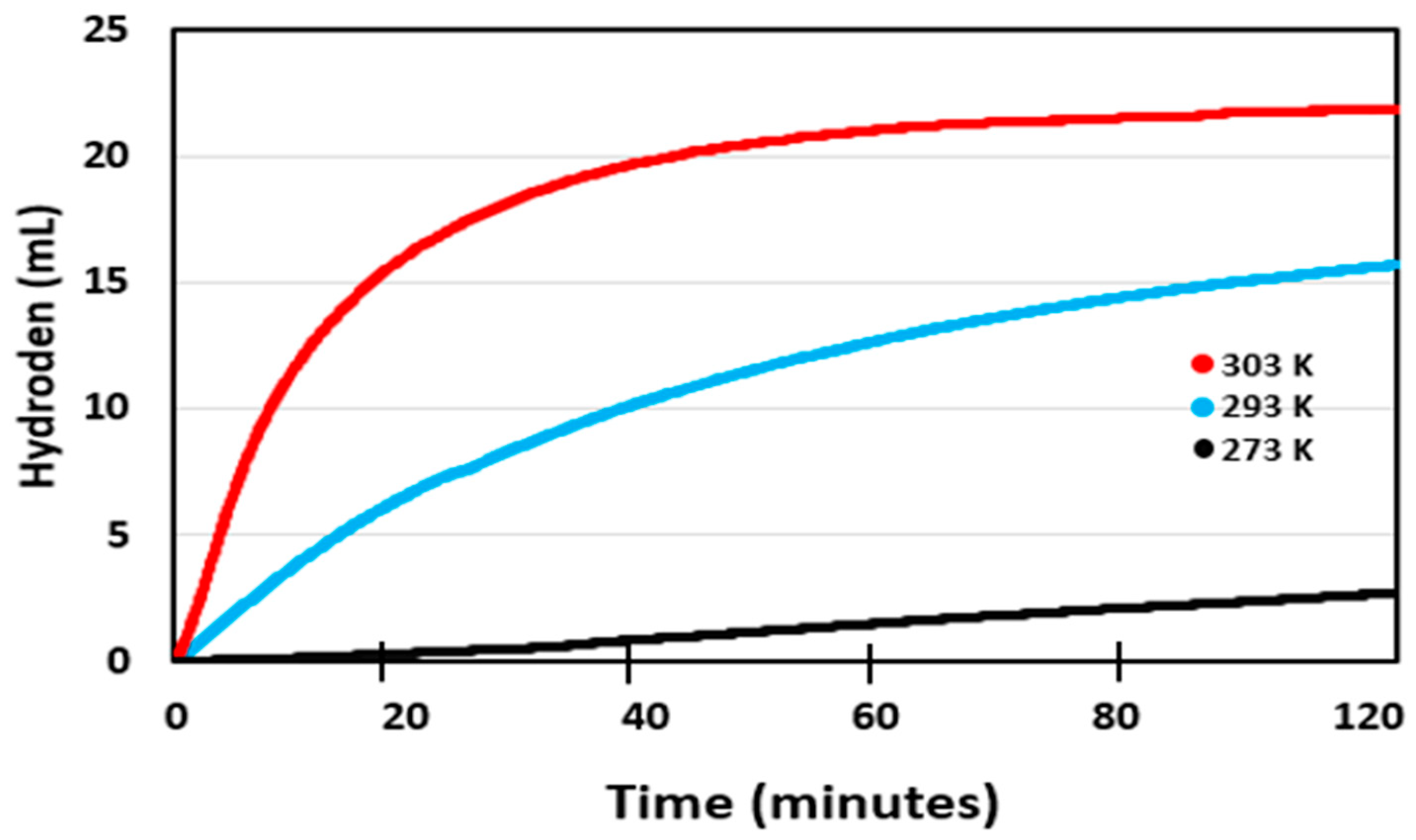

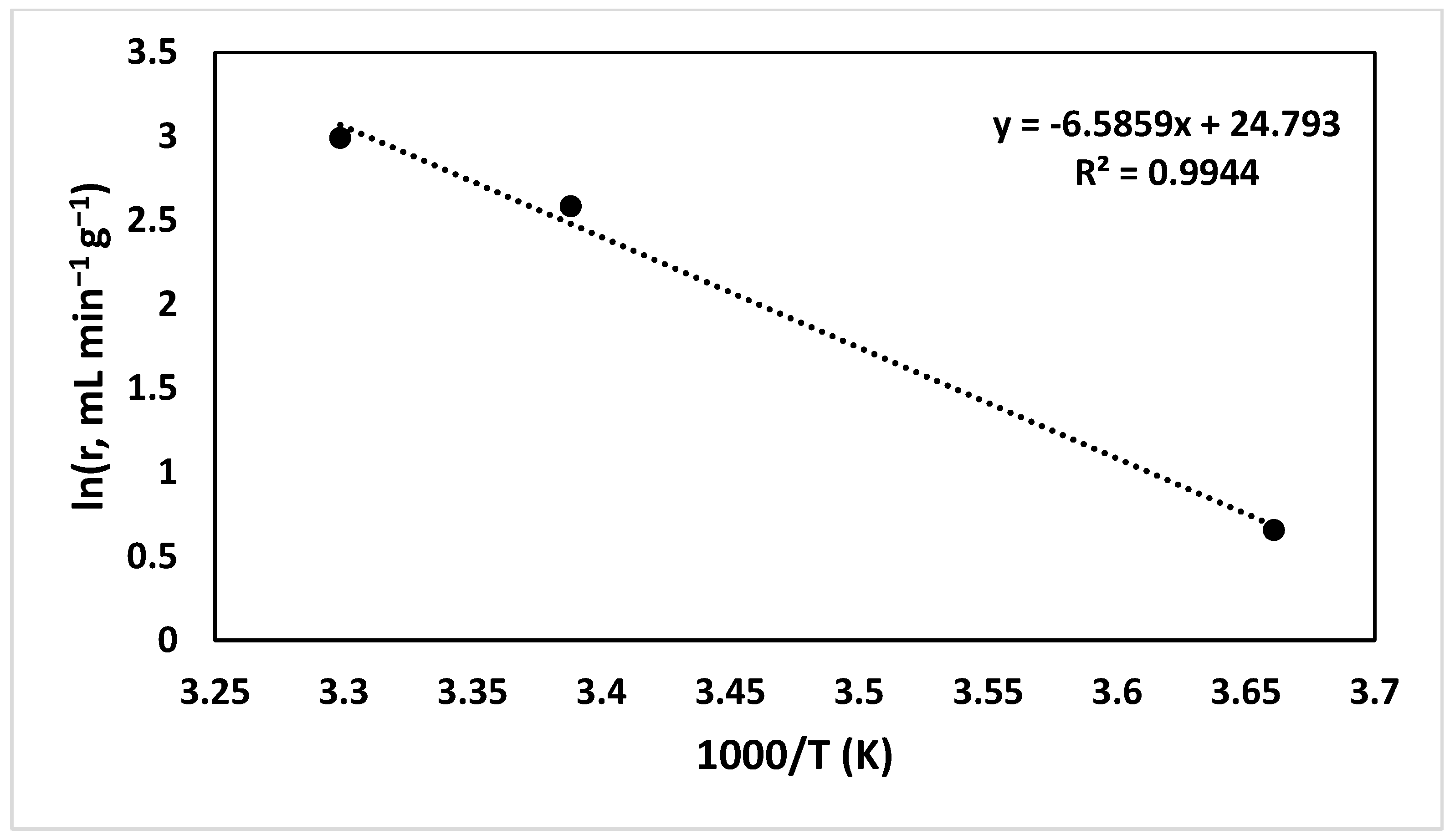

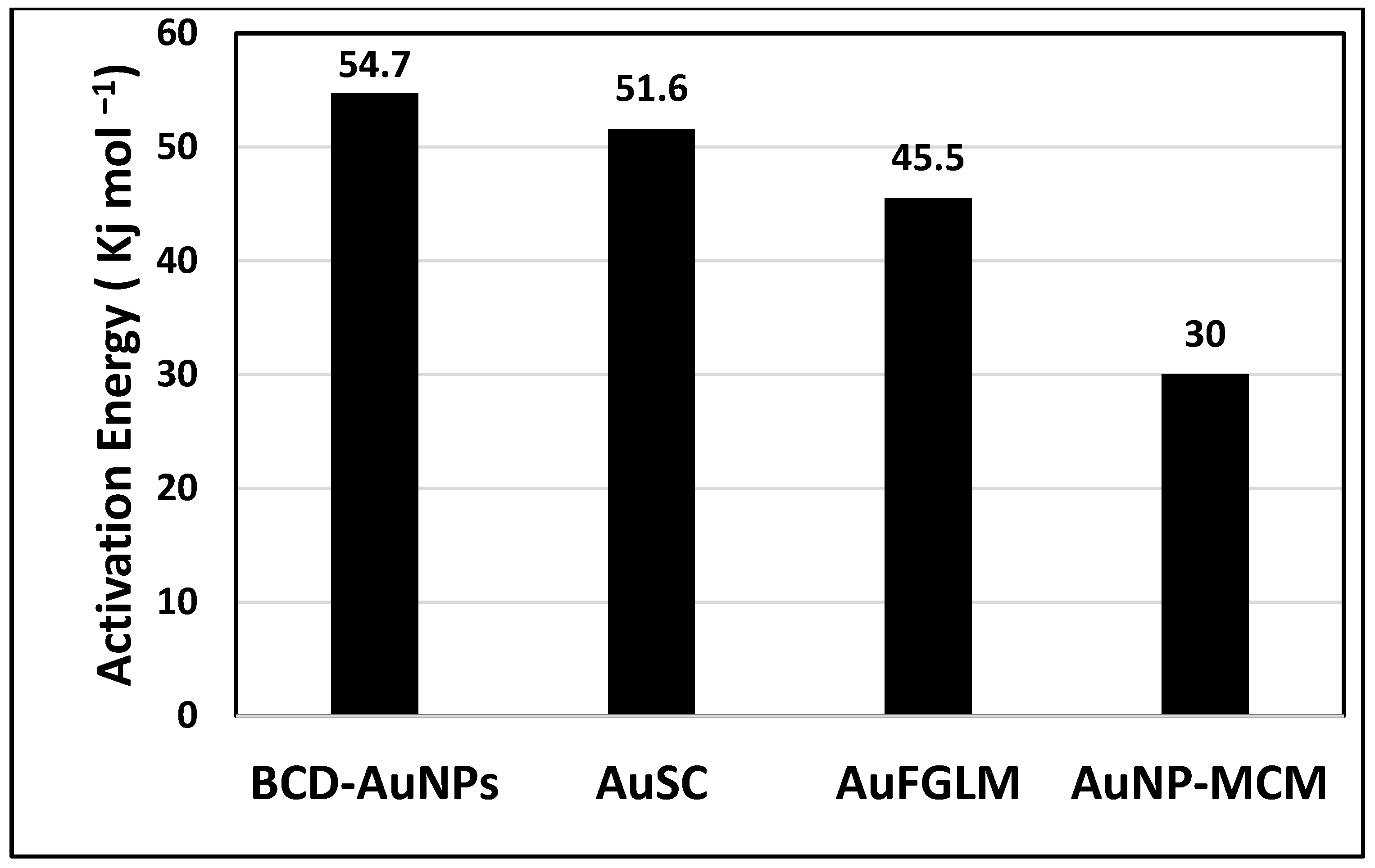

2.2. Effect of Au/CM Composite Catalyst on Hydrogen Generation Volume

| Catalyst | Ea (kJ mol−1) | Temperature (K) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AuSC | 51.6 | 273–303 | This Work |

| Silica sulfuric acid | 17 | 298–343 | [50] |

| CoCl2 | 17.5 | 293–308 | [51] |

| Pt–Pd/CNTs | 19 | 302–332 | [52] |

| Au/MWCNTs | 21.1 | 273–303 | [25] |

| Pd/C | 28 | 298–328 | [53] |

| AgNP-FCS | 37 | 273–303 | [54] |

| PtNPs | 39.2 | 283–303 | [55] |

| MWCNT Supported Co | 40.4 | 298–333 | [56] |

| Ag/MWCNTs | 44.5 | 273–303 | [26] |

| PdFGLM | 45.1 | 283–303 | [57] |

| AuFGLM | 45.5 | 283–303 | [49] |

| CuGLM | 46.8 | 283–303 | [58] |

| PtFCS | 53 | 283–303 | [59] |

| BCD-AuNP | 54.7 | 283–303 | [23] |

| Ru/Graphite | 61.1 | 398–318 | [60] |

| Pd/MWCNTs | 62.7 | 273–303 | [27] |

| Co-B | 64.9 | 283–303 | [61] |

| Ru/C | 67 | 298–358 | [62] |

2.3. Reusability of AuSC Catalyst

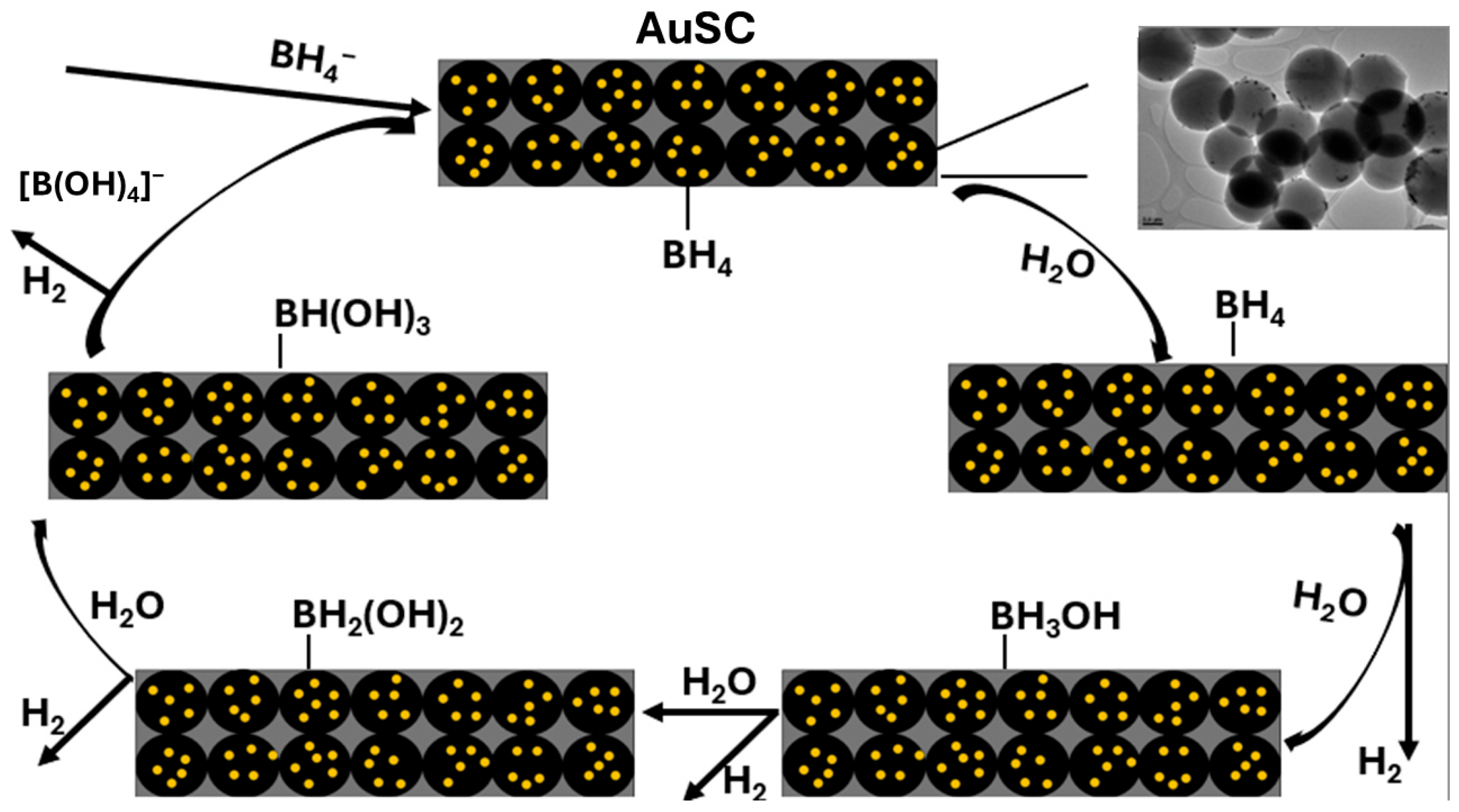

2.4. Proposed Mechanism and Structure–Function Relationship

- Adsorption of BH4− ions onto the metallic Au0 sites;

- Hydride transfer to adsorbed water or hydroxide species, forming H2 molecules;

- Desorption of hydrogen gas and the formation of surface borate intermediates, which are subsequently hydrolyzed to regenerate the active site.

3. Experimentation

3.1. Synthesis of Spherical Carbon (SC)

3.2. Synthesis of Nanoparticles (AuNPs) and Composites (AuSC)

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Catalysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Metin, O.; Ozark, S. Hydrogen generation from the hydrolysis of ammonia-borane and sodium borohydride by using water-soluble polymer-stabilized cobalt nanoclusters catalyst. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 3517–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Song, C.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, C. A Review of the Photothermal-Photovoltaic Energy Supply System for Buildings in Solar Energy Enrichment Zones. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Mollik, M.S.; Ker, P.J.; Mannan, M.; Mansor, M.; Al-Masri, H.M.K.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Wind Energy Conversions, Controls, and Applications: A Review for Sustainable Technologies and Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.W.; Toth, A.N. Direct Utilization of Geothermal Energy 2020 Worldwide Review. Geothermics 2020, 90, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, C.H.; Hwang, S.J. Review on tidal energy technologies and research subjects. China Ocean Eng. 2020, 34, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züttel, A. Hydrogen storage methods. Naturwissenschaften 2004, 91, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turakul ugli, T.J. The Importance of Alternative Solar Energy Sources and the Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Solar Panels in this Process. Int. J. Eng. Inf. Syst. (IJEAIS) 2019, 3, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ebhota, W.S.; Tabakov, P.Y. Influence of Photovoltaic Cell Technologies and Elevated Temperature on Photovoltaic System Performance. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingole, A.S.; Rakhonde, B.S. Hybrid Power Generation System Using Wind Energy and Solar Energy. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2015, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Maradin, D. Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy Sources Utilization. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, K.S.; Rugge, L.; Morrison, M.L. Influence of Behavior on Bird Mortality in Wind Energy Developments. J. Wildl. Manag. 2009, 73, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagel, A.; Bates, D.; Gawell, K. A Guide to Geothermal Energy and the Environment; Geothermal Energy Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.charleswmoore.org/pdf/Environmental%20Guide.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Shetty, C.; Priyam, A. A review on tidal energy technologies. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 56, 2774–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, F.; Dong, J.; Polinder, H. Tidal turbine generators. IntechOpen 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copping, A.E.; Hasselman, D.J.; Bangley, C.W.; Culina, J.; Carcas, M. A Probabilistic Methodology for Determining Collision Risk of Marine Animals with Tidal Energy Turbines. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veziroğlu, T.N.; Şahin, S. 21st century’s energy: Hydrogen energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 1820–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellay, C.; Dyson, P.J.; Laurenczy, G. A viable hydrogen-storage system based on selective formic acid decomposition with a ruthenium catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3966–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.; Fernandes, R.; Miotello, A. Hydrogen generation by hydrolysis of NaBH4 with efficient Co-P-B catalyst: A kinetic study. J. Power Sources 2009, 188, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Liu, M.; Chen, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, M.; Yartys, V. Recent Progress on Hydrogen Generation from the Hydrolysis of Light Metals and Hydrides. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 910, 164831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanasev, P.; Askarova, A.; Alekhina, T.; Popov, E.; Markovic, S.; Mukhametdinova, A.; Cheremisin, A.; Mukhina, E. An Overview of Hydrogen Production Methods: Focus on Hydrocarbon Feedstock. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 805–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, H.I.; Brown, H.C.; Finholt, A.E.; Gilbreath, J.R.; Hoekstra, H.R.; Hyde, E.K. Hyde, Sodium Borohydride, Its Hydrolysis and its Use as a Reducing Agent and in the Generation of Hydrogen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 75, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.; Long, J.M.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Beta-Cyclodextrin-Assisted Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticle Network and Its Application in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, Q.; Biehler, E.; Elzamzami, A.; Huff, C.; Long, J.M.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Catalytic Activity of Beta-Cyclodextrin-Gold Nanoparticles Network in Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Catalysts 2021, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.; Dushatinski, T.; Barzanji, A.; Abdel-Fattah, N.; Barzanji, K. Pretreatment of Gold Nanoparticle Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Composites for Catalytic Activity Toward Hydrogen Generation Reaction. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2017, 6, M69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.; Dushantinski, T.; Abdel-Fattah, T. Gold nanoparticle/multi-walled carbon nanotube composite as novel catalyst for hydrogen evolution reactions. ECS J. Solid-State Sci. Technol. 2017, 42, 18985–18990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.; Long, J.; Abdelrahman, A.; Heyman, A.; Fattah, T. Silver Nanoparticle/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Composite as Catalyst for Hydrogen Production. ECS J. Solid-State Sci. Technol. 2017, 6, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.; Long, J.; Heyman, A.; Fattah, T. Palladium Nanoparticle Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Composite as Catalyst for Hydrogen Production by the Hydrolysis of Sodium Borohydride. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 4635–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, C.; Ingoglia, R.; Schipilliti, L.; Crisafulli, C.; Neri, G.; Galvagno, S. Selective Hydrogenation of α,β-Unsaturated Ketone to α,β-Unsaturated Alcohol on Gold-Supported Iron Oxide Catalysts: Role of the Support. J. Catal. 2005, 236, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-H.; Yang, T.C.K.; Wu, H.-E.; Chiang, H.-C. Catalysis of Oxidation of Carbon Monoxide on Supported Gold Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 166, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torigoe, K.; Esumi, K. Preparation and Catalytic Effect of Gold Nanoparticles in Water Dissolving Carbon Disulfide. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 2862–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, F.; Schreier, S.; Hanzlik, M.; Savinova, E.R.; Weinkauf, S.; Stimming, U. Influence of particle agglomeration on the catalytic activity of carbon-supported Pt nanoparticles in CO monolayer oxidation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Fortunato, M.E.; Xu, H.; Bang, J.H.; Suslick, K.S. Carbon Microspheres as Supercapacitors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 20481–20486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargan, A.; Yan, Y.; Hui, C.W.; McKay, G. A Review: Synthesis of Carbon-Based Nano and Micro Materials by High Temperature and High Pressure. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 12689–12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolini, E. Carbon Supports for Low-Temperature Fuel Cell Catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 88, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiangfeng, C.; Mingmei, W. Highly Sensitive Gas Sensors Based on Hollow SnO2 Spheres Prepared by Carbon Sphere Template Method. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 120, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Vasudevan, S.V.; Cao, M.; Cai, J.; Mao, H.; Bu, Q. Microwave-Assisted Efficient Fructose–HMF Conversion in Water over Sulfonated Carbon Microsphere Catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 15344–15356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, I.A.; Miao, W.; Chen, K.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Han, S. Carbon Nanospheres Supported Bimetallic Pt-Co as an Efficient Catalyst for NaBH4 Hydrolysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 540, 148296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qiu, S.; Chua, Y.S.; Xia, Y.; Zou, Y.; Xu, F.; Sun, L.; Chu, H. Co–B Supported on Waxberry-Like Hierarchical Porous Carbon Microspheres: An Efficient Catalyst for Hydrogen Generation via Sodium Borohydride Hydrolysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 319, 129399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zied, B.M.; Ali, T.T.; Adly, L. Sodium Borohydride Hydrolysis over Mesoporous Spherical Carbon Obtained from Jasmine Flower Extract. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 10829–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Austin, N.; Li, M.; Song, Y.; House, S.D.; Bernhard, S.; Yang, J.C.; Mpourmpakis, G.; Jin, R. Influence of Atomic-Level Morphology on Catalysis: The Case of Sphere and Rod-Like Gold Nanoclusters for CO2 Electroreduction. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4996–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, R.F.L.; Paladino, E.E.; Maliska, C.R. A Computational Study of the Interfacial Heat or Mass Transfer in Spherical and Deformed Fluid Particles Flowing at Moderate Re Numbers. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 138, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titirici, M.-M.; White, R.J.; Brun, N.; Budari, V.L.; Su, D.S.; del Monte, F.; Clark, J.H.; MacLachlan, M.J. Sustainable carbon materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 250–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Okejiri, F.; Qiao, Z.-A.; Dai, S. Tailoring Polymer Colloids Derived Porous Carbon Spheres Based on Specific Chemical Reactions. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, M.A.; Darain, F.; Islam, N.; Young, D.J. Nano/mesoporous carbon from rice starch for voltammetric detection of ascorbic acid. Molecules 2018, 23, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Lu, C.J.; Xia, Z.P.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Z. X-ray Diffraction Patterns of Graphite and Turbostratic Carbon. Carbon 2007, 45, 1686–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P.J. Kinetics of Polyesterification: A Study of the Effects of Molecular Weight and Viscosity on Reaction Rate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1939, 61, 3334–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, A.; Jackson, K.; Morgan, C.; Anderson, A.; Britt, D.W. A Review of Metal and Metal-Oxide Nanoparticle Coating Technologies to Inhibit Agglomeration and Increase Bioactivity for Agricultural Applications. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehler, E.; Quach, Q.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Gold Nanoparticles AuNP Decorated on Fused Graphene-like Materials for Application in a Hydrogen Generation. Materials 2023, 16, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biehler, E.; Quach, Q.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Gold Nanoparticle Mesoporous Carbon Composite as Catalyst for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Molecules 2024, 29, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, J.; Roy, B.; Sharma, P. Efficient hydrogen generation from sodium borohydride hydrolysis using silica sulfuric acid catalyst. J. Power Sources 2015, 275, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.; Brown, J.B.; Lyons, C.J. Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Sodium Borohydride. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1960, 52, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Alonso, R.; Sicurelli, A.; Callone, E.; Carturan, G.; Raj, R. A picoscale catalyst for hydrogen generation from NaBH4 for fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Patton, B.; Zanchetta, C.; Fernandes, R.; Guella, G.; Kale, A.; Miotello, A. Pd-C power and thin film catalysts for hydrogen production by hydrolysis of sodium borohydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehler, E.; Quach, Q.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Silver-Nanoparticle-Decorated Fused Carbon Sphere Composite as a Catalyst for Hydrogen Generation. Energies 2023, 16, 5053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, C.; Biehler, E.; Quach, Q.; Long, J.M.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Synthesis of Highly Dispersive Platinum Nanoparticles and their Application in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 610, 125734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Shen, P.K.; Wei, Z. Accurately measuring the hydrogen generation rate for hydrolysis of sodium borohydride on multi-walled carbon nanotubes/Co-B catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 7110–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, Q.; Biehler, E.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Synthesis of Palladium Nanoparticles Supported over Fused Graphene-like Material for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, Q.; Biehler, E.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles Supported over Graphene-like Material Composite as a Catalyst for Hydrogen Evolution. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehler, E.; Quach, Q.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles Supported on Fused Nanosized Carbon Spheres Derived from Sustainable Source for Application in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Dai, H.-B.; Ma, L.-P.; Wang, P.; Cheng, H.-M. Hydrogen generation from sodium borohydride solution using a ruthenium supported graphite catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 3023–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.U.; Kim, R.K.; Cho, E.A.; Kim, H.-J.; Nam, S.-W.; Oh, I.-H.; Hong, S.-A.; Kim, S.H. A study on hydrogen generation from NaBH4 solution using the high-performance Co-B catalyst. J. Power Sources 2005, 144, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S.; Delgass, W.N.; Fisher, T.S.; Gore, J.P. Kinetics of Ru-catalyzed sodium borohydride hydrolysis. J. Power Sources 2007, 164, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmakiran, M.; Özkar, S. Zeolite-Confined Ruthenium(0) Nanoclusters Catalyst: Record Catalytic Activity, Reusability, and Lifetime in Hydrogen Generation from the Hydrolysis of Sodium Borohydride. Langmuir 2009, 25, 2667–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Ma, Z.; Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Ding, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Optimized Pt–Co/BN Catalysts for Efficient NaBH4 Hydrolysis. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2400313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenar, M.E.; Şahin, Ö.; Kutluay, S.; Genceli Güner, F.E. Boosting H2 Generation via NaBH4 Hydrolysis Using Co–Zr–B@Co3O4 as a Novel Catalyst: Insights on Characterization, Catalytic Evaluation, Kinetics and Reusability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 174, 151456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenar, M.E.; Kutluay, S.; Şahin, Ö.; Genceli Güner, F.E. Cobalt–Boron–Fluoride Decorated Graphitic Carbon Nitride Composite as a Promising Candidate Catalyst for Highly Efficient Hydrogen Production via NaBH4 Hydrolysis Process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 90, 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xu, F.; Liu, X. Superior Hydrogen Generation from Sodium Borohydride Hydrolysis Catalyzed by the Bimetallic Co–Ru/C Nanocomposite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 25376–25384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, T.M.; Biehler, E. Carbon Based Supports for Metal Nanoparticles for Hydrogen Generation Reactions Review. Adv. Carbon J. 2024, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, Q.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Silver Nanoparticles functionalized Nanoporous Silica Nanoparticle grown over Graphene Oxide for enhancing Antibacterial effect. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biehler, E.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M. Glucose-Mediated Synthesis of Spherical Carbon Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles as Catalyst in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121141

Biehler E, Abdel-Fattah TM. Glucose-Mediated Synthesis of Spherical Carbon Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles as Catalyst in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121141

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiehler, Erik, and Tarek M. Abdel-Fattah. 2025. "Glucose-Mediated Synthesis of Spherical Carbon Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles as Catalyst in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121141

APA StyleBiehler, E., & Abdel-Fattah, T. M. (2025). Glucose-Mediated Synthesis of Spherical Carbon Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles as Catalyst in a Hydrogen Generation Reaction. Catalysts, 15(12), 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121141