Enhanced Hydrogen Desorption Performance of AlH3 via MXene Catalysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

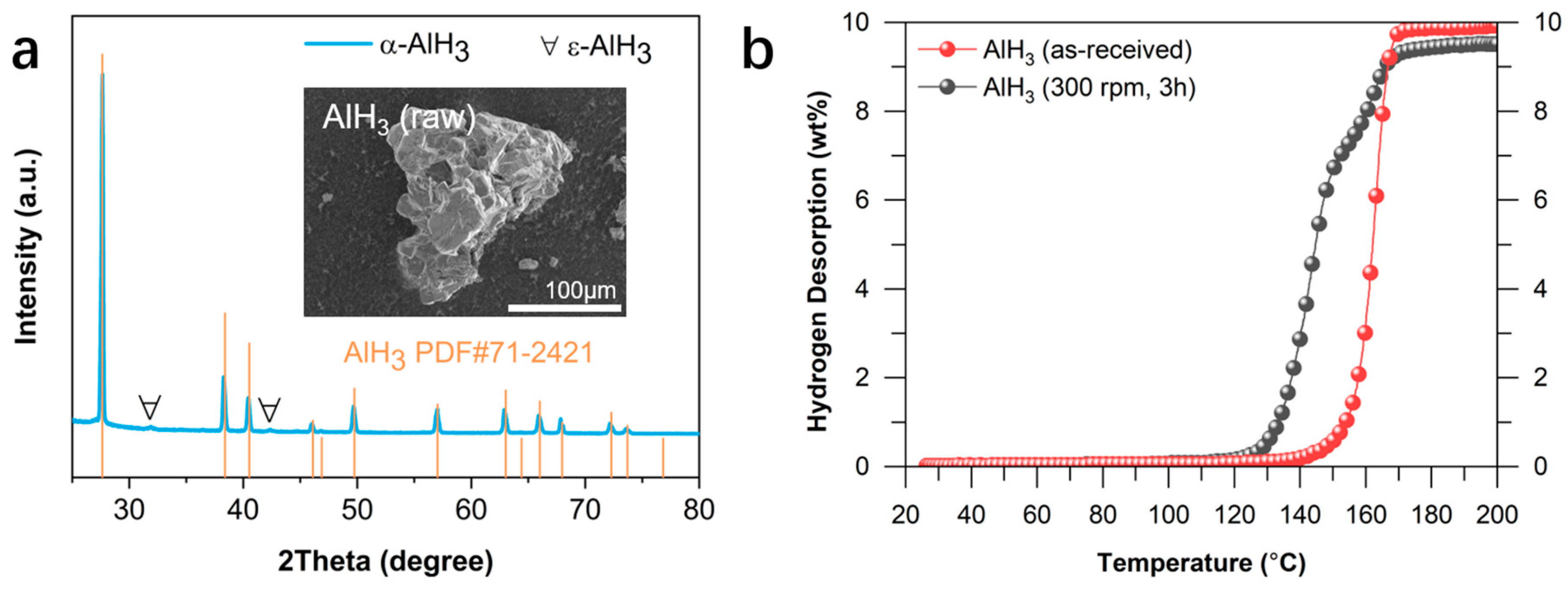

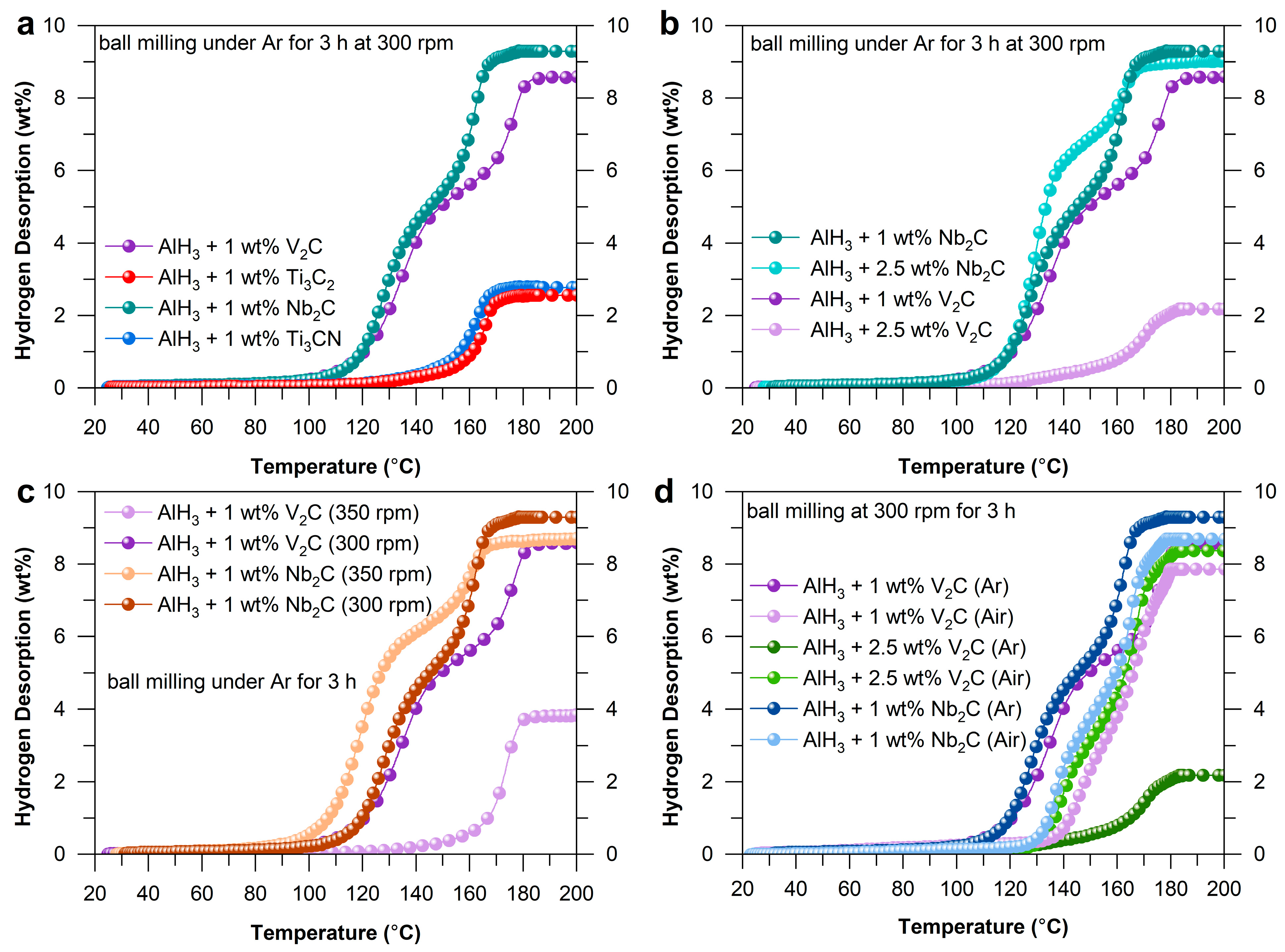

2.1. Hydrogen Desorption Properties of AlH3 Catalyzed by MXenes

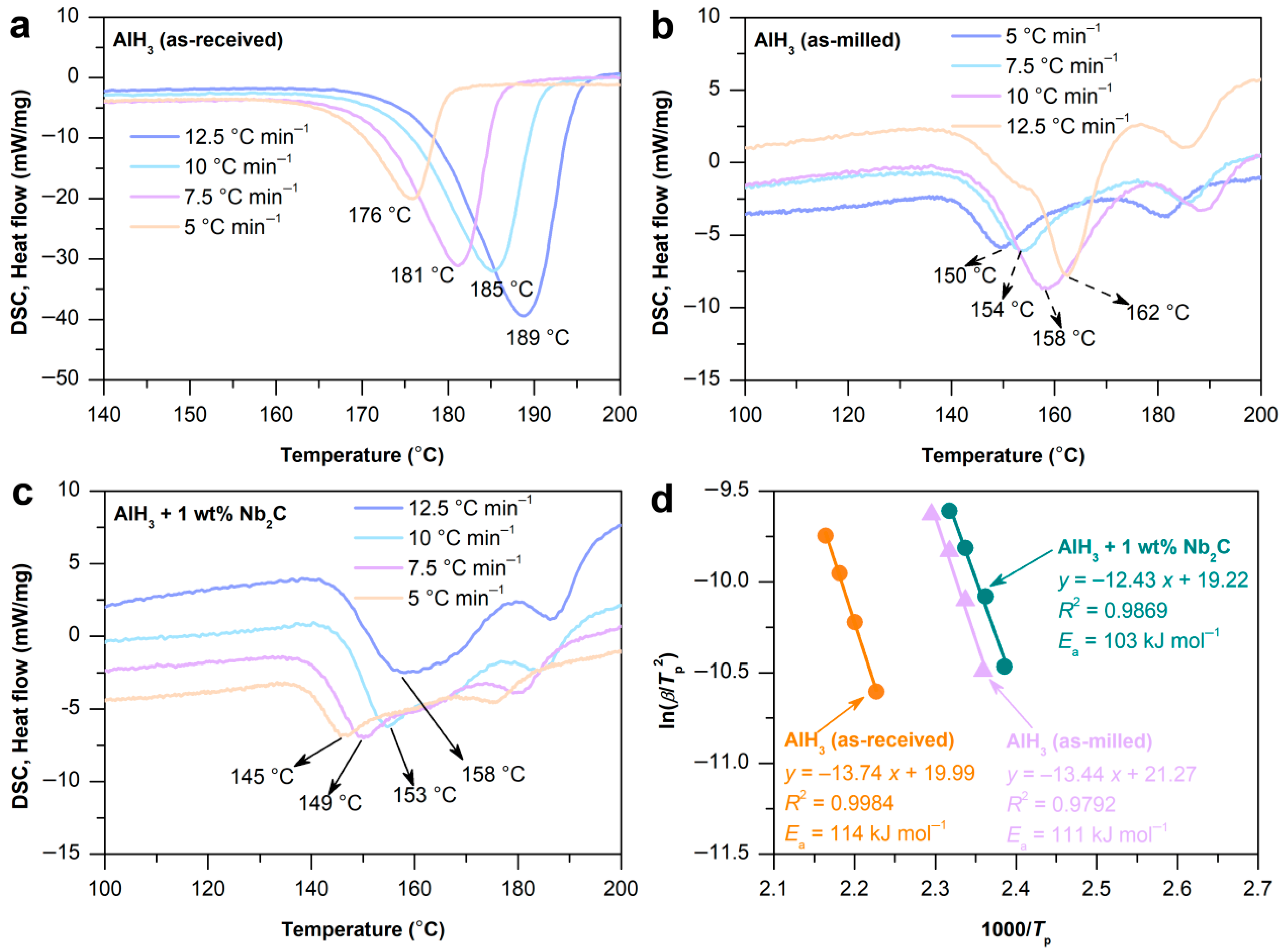

2.2. Hydrogen Desorption Kinetics and Activation Energy of AlH3 + 1 wt% Nb2C

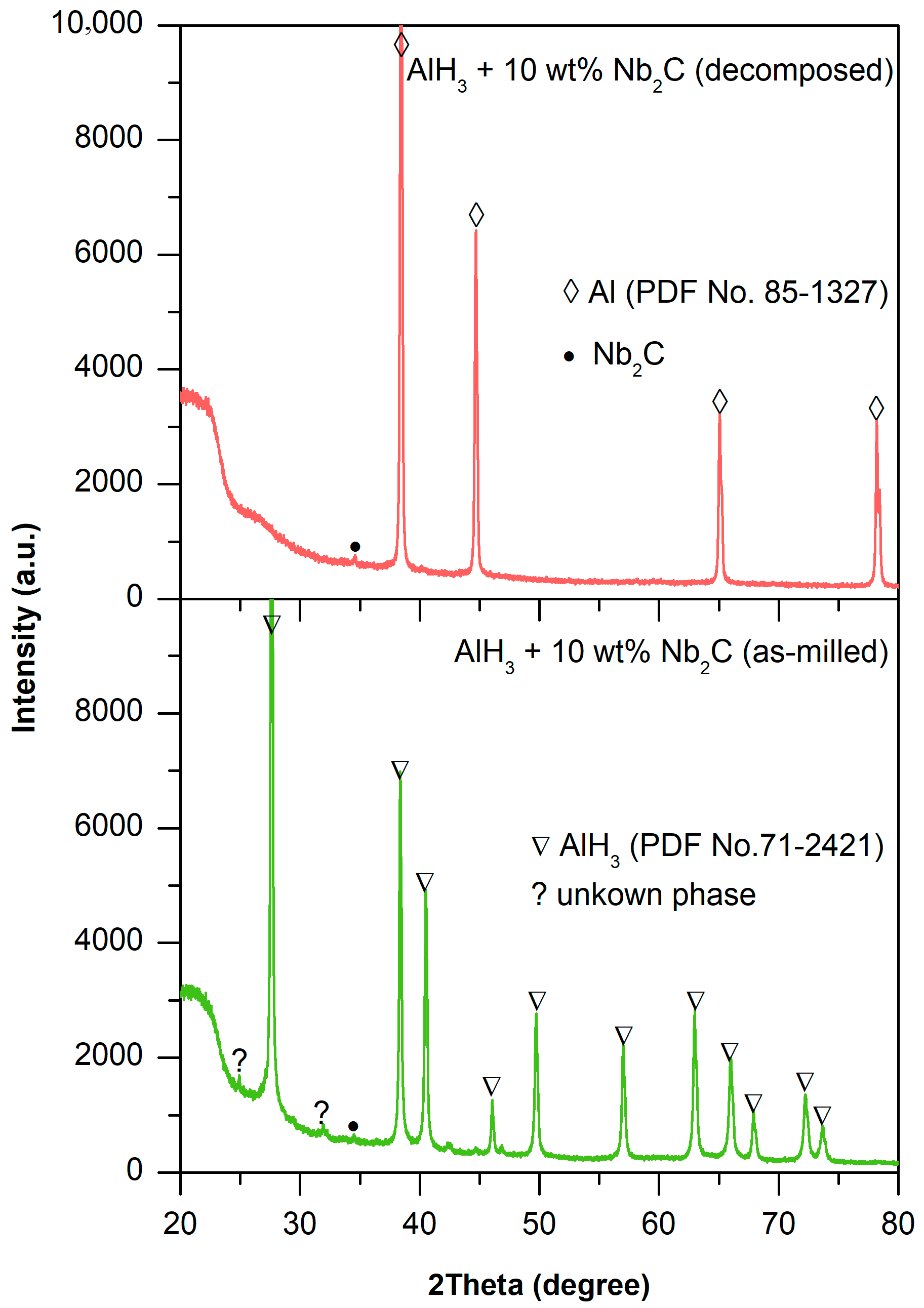

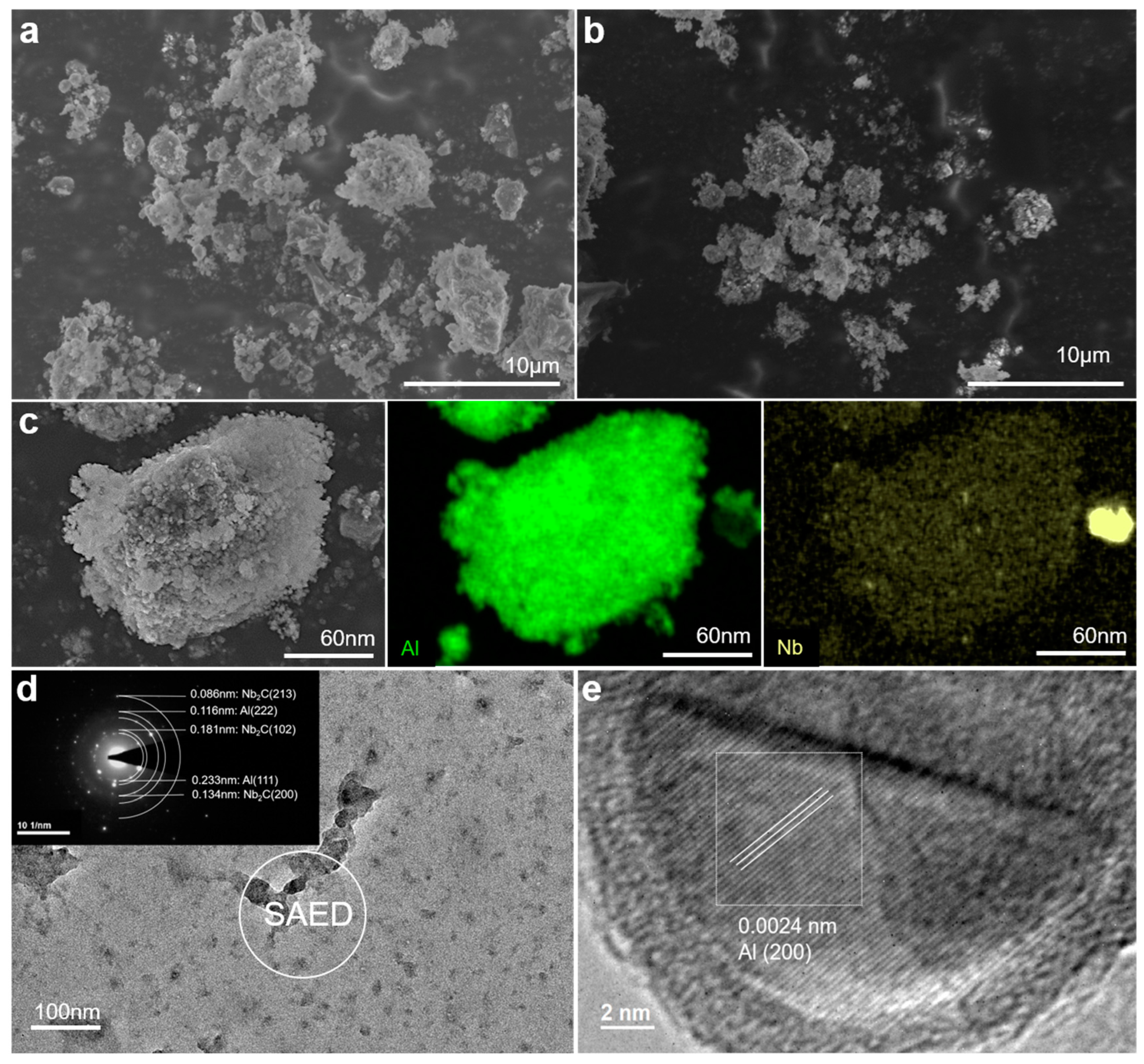

2.3. Microstructural Study on the Catalysis Mechanism in AlH3 + 1 wt% Nb2C

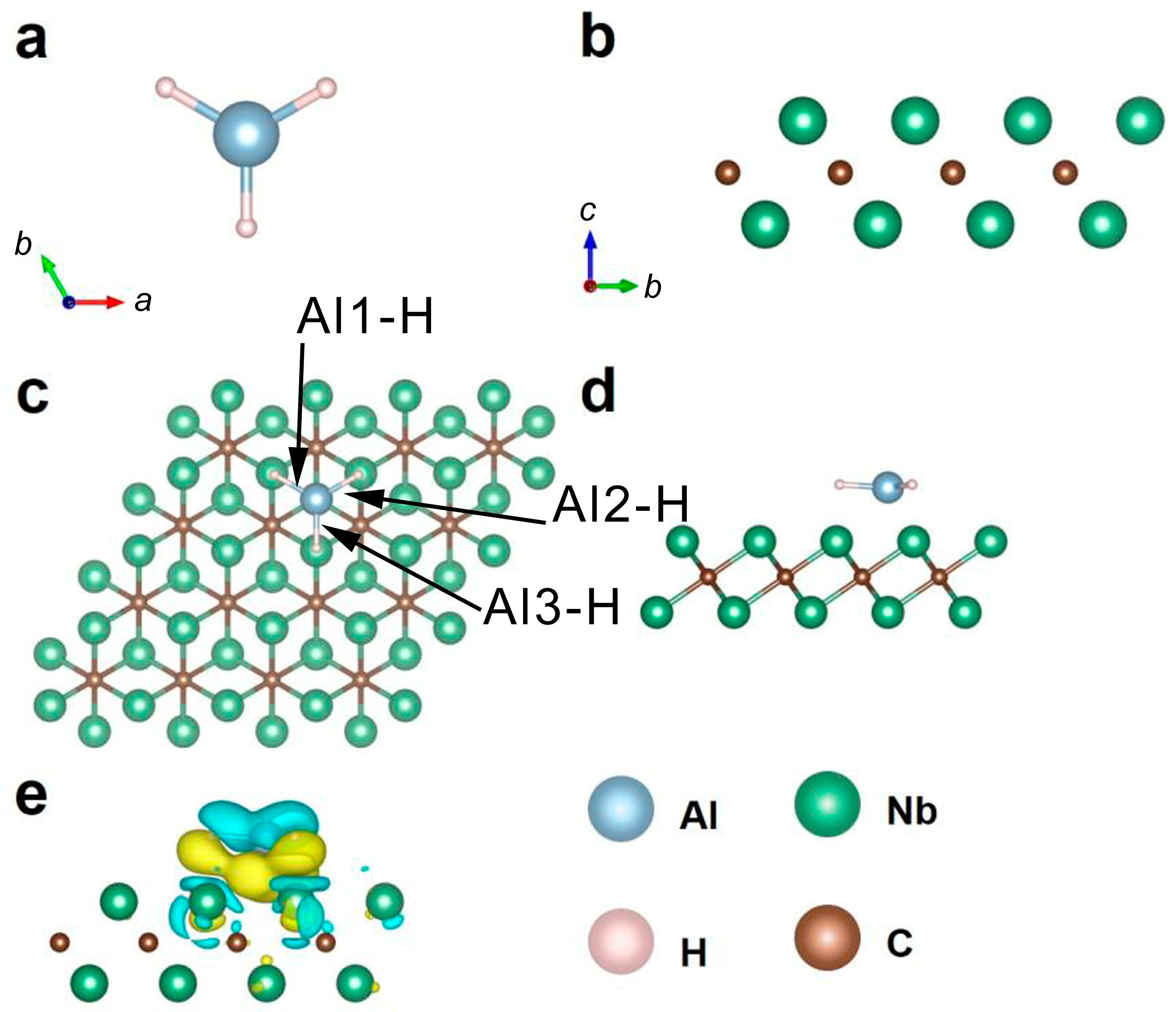

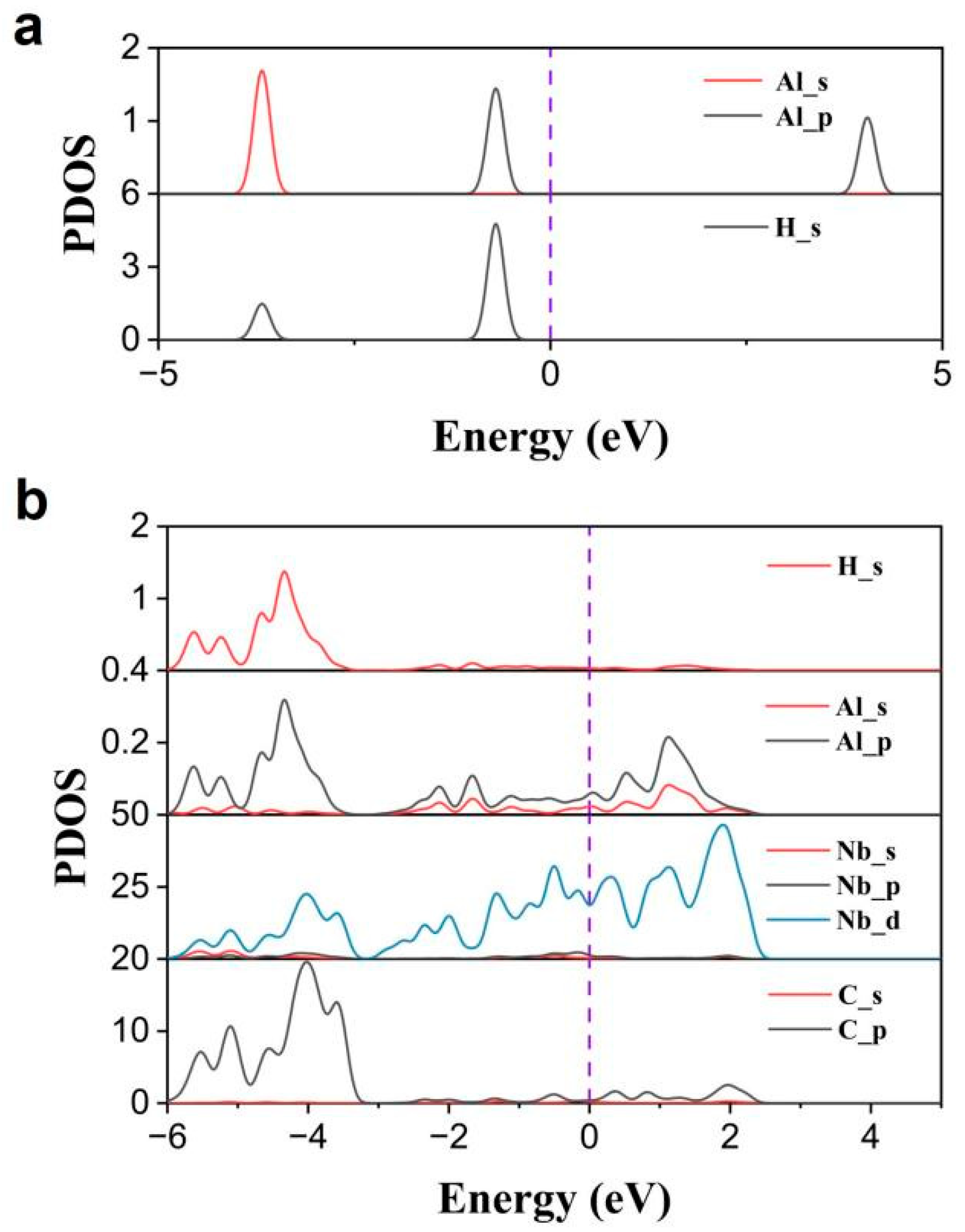

2.4. Computational Study on the Catalysis Mechanism in AlH3 + 1 wt% Nb2C

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. Sample Characterization

3.3. Hydrogen Desorption Performance Testing

3.4. Computational Details

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, A.P.; Li, S.; Xie, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, P.J.-H.; Zhang, Q. Hydrogen as the nexus of future sustainable transport and energy systems. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2025, 2, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhong, L. Decarbonizing urban residential communities with green hydrogen systems. Nat. Cities 2025, 2, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.; Liebreich, M.; Kammen, D.M.; Ekins, P.; McKenna, R.; Staffell, I. Realistic roles for hydrogen in the future energy transition. Nat. Rev. Clean Tech. 2025, 1, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-X.; Li, X.-G.; Yao, Q.-L.; Lu, Z.-H.; Zhang, N.; Xia, J.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, K.; Liu, H.-Z.; et al. 2022 roadmap on hydrogen energy from production to utilizations. Rare Met. 2022, 41, 3251–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasleem, S.; Bongu, C.S.; Krishnan, M.R.; Alsharaeh, E.H. Navigating the hydrogen prospect: A comprehensive review of sustainable source-based production technologies, transport solutions, advanced storage mechanisms, and CCUS integration. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 97, 166–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, P.K.; Chandu, B.; Motapothula, M.R.; Puvvada, N. Potential Benefits, Challenges and Perspectives of Various Methods and Materials Used for Hydrogen Storage. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 2630–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, A.S.; Phillips, A.D.; Brandon, M.P.; Pryce, M.T.; Carton, J.G. Recent challenges and development of technical and technoeconomic aspects for hydrogen storage, insights at different scales; A state of art review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 70, 786–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.-J.; Wu, H.-C.; Liu, Y.-T.; Ding, Y.-Y.; Yao, Q.-L.; Metin, O.; Lu, Z.-H. Hydrogen production from chemical hydrogen storage materials over copper-based catalysts. cMat 2024, 1, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Peng, W.; Hua, Z.; Zheng, J. A comparative analysis of the regulations, codes and standards for on-board high-pressure hydrogen storage cylinders. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Sharma, P.; Bora, B.J.; Tran, V.D.; Truong, T.H.; Le, H.C.; Nguyen, P.Q.P. Fueling the future: A comprehensive review of hydrogen energy systems and their challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, S.J. Advancements in hydrogen storage technologies: A comprehensive review of materials, methods, and economic policy. Nano Today 2024, 56, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Sheng, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; Zhao, D. An overview of RE-Mg-based alloys for hydrogen storage: Structure, properties, progresses and perspectives. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Z. V–Ti-Based Solid Solution Alloys for Solid-State Hydrogen Storage. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, Z. Carbon-based materials for Mg-based solid-state hydrogen storage strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 645–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, H.; Yang, H.; Du, W.; Zheng, Y.; Huo, K.; Shaw, L.L. MOFs-Based Materials for Solid-State Hydrogen Storage: Strategies and Perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdechafik, E.H.; Ait Ousaleh, H.; Mehmood, S.; Filali Baba, Y.; Bürger, I.; Linder, M.; Faik, A. An analytical review of recent advancements on solid-state hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ding, Z.; Li, Y.T.; Li, S.Y.; Wu, P.K.; Hou, Q.H.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, B.; Huo, K.F.; Du, W.J.; et al. Recent advances in kinetic and thermodynamic regulation of magnesium hydride for hydrogen storage. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 2906–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.J.; Lin, H.J.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Zhu, M. Amorphous alloys for hydrogen storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 941, 168945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanullang, M.; Prost, L. Nanomaterials for on-board solid-state hydrogen storage applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 29808–29846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Jiang, L.-J.; Li, P.; Yuan, H.-P.; Li, Z.-N.; Zhang, J.-X. Heat treatment effect on structural evolution and hydrogen sorption properties of Y0.5La0.2Mg0.3−xNi2 compound. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J.-M.; Paul-Boncour, V.; Cuevas, F.; Zhang, J.; Latroche, M. LaNi5 related AB5 compounds: Structure, properties and applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 862, 158163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, L.; Guo, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. Hydrogen storage properties of Ti-Mn-based AB2-type Laves phase alloys. Chin. J. Rare Met. 2019, 43, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, H.; Gao, M.; Wang, Q. Advanced hydrogen storage alloys for Ni/MH rechargeable batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 4743–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Shao, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zou, J.; Zhang, K.; Lin, X. Enhancing hydrogen sorption kinetics of Ti-based hydrogen storage alloy tanks through an optimized bulk-powder combination strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Cao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Jiang, Z.; Zhan, L.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Study on low-vanadium Ti–Zr–Mn–Cr–V based alloys for high-density hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 1710–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Cao, Z.; Xiao, X.; Zhan, L.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Development of Ti-Zr-Mn-Cr-V based alloys for high-density hydrogen storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 875, 160035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Luo, H.; Wu, Z.; Ning, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; et al. Effect of Ti0.9Zr0.1Mn1.5V0.3 alloy catalyst on hydrogen storage kinetics and cycling stability of magnesium hydride. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 479, 147893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-S.; Park, K.B.; Park, H.-K. Density functional theory study on the role of ternary alloying elements in TiFe-based hydrogen storage alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2021, 92, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhao, D. Effects of adding over-stoichiometrical Ti and substituting Fe with Mn partly on structure and hydrogen storage performances of TiFe alloy. Renew. Energy 2019, 135, 1481–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Qi, J.; Lei, N.; Guo, S.; Li, J.; Xiao, X.; Ouyang, L. Advanced Mg-based materials for energy storage: Fundamental, progresses, challenges and perspectives. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 148, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Zou, Y.; Xiang, C.; Xu, F.; Sun, L.; Chua, Y.S. Vanadium induces Ni-Co MOF formation from a NiCo LDH to catalytically enhance the MgH2 hydrogen storage performance. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 4020–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Yao, X. Enhancing hydrogen storage performance of magnesium-based materials: A review on nanostructuring and catalytic modification. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 510–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhao, D.; Sun, H.; Sheng, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y. Two-dimensional material MXene and its derivatives enhance the hydrogen storage properties of MgH2: A review and summary. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, B.; Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zou, J. Nanostructured MXene-based materials for boosting hydrogen sorption properties of Mg/MgH2. Mater. Rep. Energy 2024, 4, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Guan, S.; Zhao, S.; Ji, L.; Peng, Q.; Han, S.; Fan, Y.; Liu, B. Effectively enhanced catalytic effect of sulfur doped Ti3C2 on the kinetics and cyclic stability of hydrogen storage in MgH2. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 13, 1843–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, B.; Xiang, C.; Sun, L.; Xu, F.; Yu, T. Hydrogen storage performance of MgH2 under catalysis by highly dispersed nickel-nanoparticle–doped hollow spherical vanadium nitride. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 5132–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Chen, L. Promoting catalysis in magnesium hydride for solid-state hydrogen storage through manipulating the elements of high entropy oxides. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 5038–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, Z.; Han, C.; Long, S.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.A.; Pan, F. Constructing VO/V2O3 interface to enhance hydrogen storage performance of MgH2. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 4877–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.A.; Li, Q.; Pan, F. N/S co-doped Nb2CTx MXene as the effective catalyst for improving the hydrogen storage performance of MgH2. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2024, 190, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Sun, Y.; Ning, H.; Luo, H.; Wei, Q.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Layered MoS2-supported and metallic Ni-doped MgH2 towards enhanced hydrogen storage kinetics and cycling stability. J. Magnes. Alloys 2025, 13, 4517–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Liu, J.; Guo, D.; Yang, L.; Sun, L.; Li, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, H. High catalytic activity derived from TiNbAlC MAX towards improving the hydrogen storage properties of MgH2. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 955, 170297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Duan, X.; Wu, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; Zhou, W.; Guo, J.; Ismail, M. Exfoliation of compact layered Ti2VAlC2 MAX to open layered Ti2VC2 MXene towards enhancing the hydrogen storage properties of MgH2. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Tang, H.; Duan, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, H. Hydrogen release and uptake of MgH2 modified by Ti3CN MXene. Inorganics 2023, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, H.; Xu, L.; Luo, H.; He, S.; Duan, X.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Lan, Z.; Guo, J. Two-dimensional vanadium carbide for simultaneously tailoring the hydrogen sorption thermodynamics and kinetics of magnesium hydride. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Z.-L.; Ning, H.; Luo, H.; Wei, Q.-Q.; Qing, P.-L.; Huang, X.-T.; Wang, X.-H.; Li, G.-X.; Huang, C.-K.; et al. Reversible hydrogen storage in AlH3−LiNH2 system. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 5022–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Guan, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Fan, G.; Fan, Y.; Liu, B. Excellent catalytic effect of V2C MXene on dehydrogenation performance of α-AlH3. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 56, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C.; Yin, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Liang, F.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y. Heterojunction synergistic catalysis of MXene-supported PrF3 nanosheets for the efficient hydrogen storage of AlH3. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 9546–9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Sheng, P.; Wang, X.; Jiang, T.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; et al. Directed stabilization by air-milling and catalyzed decomposition by layered titanium carbide toward low-temperature and high-capacity hydrogen storage of aluminum hydride. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 42102–42112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Lu, Z.; Xu, L.; Sheng, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Huang, C.; et al. Achieving both high hydrogen capacity and low decomposition temperature of the metastable AlH3 by proper ball milling with TiB2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 48, 3541–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Lu, C.; Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Lan, Z.; Guo, J. Aluminum hydride for solid-state hydrogen storage: Structure, synthesis, thermodynamics, kinetics, and regeneration. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 52, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, N.S.; Noor, N.A.M.; Omar, N.A.M.Y.; Omar, Z.; Ismail, M. Influence of CeCl3 incorporation on the dehydrogenation characteristics of NaAlH4 for solid-state hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 105, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Z.; Jiang, R.; Shi, L.; Feng, Y.; Dong, H.; Yang, L.; Piao, M.; Xiao, X. Sodium alanate in-situ doped with Ti2C MXene with enhanced hydrogen storage properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-Y.; Ding, Z.-Q.; Xie, Y.-J.; Li, J.-F.; Huang, C.-K.; Cai, W.-T.; Liu, H.-Z.; Guo, J. Cerium hydride generated during ball milling and enhanced by graphene for tailoring hydrogen sorption properties of sodium alanate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 4168–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Ju, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, Z. Enhanced hydrogen storage of alanates: Recent progress and future perspectives. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2021, 31, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Yang, Y.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Sun, W.; Liang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; et al. Superior reversible hydrogen storage in eutectic LiBH4–KBH4 system via Ni–based catalysts synergized with graphene. Mater. Today Catal. 2025, 9, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Xia, A.; Lv, M.; Ma, Z.; Liu, M. Enhanced reversible hydrogen storage in LiBH4-Mg(BH4)2 composite with V2C-Mxene. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487, 150629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, M.H.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Li, Z.L.; Yang, Y.X.; Li, Y.Z.; Liu, H.F.; Gao, M.X. Reactive destabilization and bidirectional catalyzation for reversible hydrogen storage of LiBH4 by novel waxberry-like nano-additive assembled from ultrafine Fe3O4 particles. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2024, 173, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, B.; Huang, H.; Yu, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Yuan, J.; Xia, G.; Wu, Y. Excellent low-temperature dehydrogenation performance and reversibility of 0.55LiBH4-0.45Mg(BH4)2 composite catalyzed by few-layer Ti2C. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 972, 172896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, L.; Luo, H.; Deng, J.; Li, G.; Ning, H.; Fan, Y.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; Zhou, W.; et al. Hybrid of bulk NbC and layered Nb4C3 MXene for tailoring the hydrogen storage kinetics and reversibility of Li–Mg–B–H composite: An experimental and theoretical study. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2024, 194, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Yang, Y.; Lu, L.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Tao, X.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; Zhou, W.; et al. Highly-dispersed nano-TiB2 derived from the two-dimensional Ti3CN MXene for tailoring the kinetics and reversibility of the Li-Mg-B-H hydrogen storage material. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 610, 155581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.-W.; Luo, H.; Li, G.-X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.-H.; Huang, C.-K.; Lan, Z.-Q.; Zhou, W.-Z.; Guo, J.; Ismail, M.; et al. Layered niobium carbide enabling excellent kinetics and cycling stability of Li–Mg–B–H hydrogen storage material. Rare Met. 2023, 43, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Yang, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; et al. Space-Confined Metal Ion Strategy for Carbon Materials Derived from Cobalt Benzimidazole Frameworks with High Desalination Performance in Simulated Seawater. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2301011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangu, K.K.; Maddila, S.; Mukkamala, S.B.; Jonnalagadda, S.B. Characteristics of MOF, MWCNT and Graphene Containing Materials for Hydrogen Storage: A Review. J. Energy Chem. 2019, 30, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, R.H.; Zakhidov, A.A.; de Heer, W.A. Carbon nanotubes—The route toward applications. Science 2002, 297, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, Y.Y.; Liu, M.; Cong, H.T.; Cheng, H.M.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Hydrogen storage in single-walled carbon nanotubes at room temperature. Science 1999, 286, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A.C.; Jones, K.M.; Bekkedahl, T.A.; Kiang, C.H.; Bethune, D.S.; Heben, M.J. Storage of hydrogen in single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nature 1997, 386, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Kirlikovali, K.O.; Idrees, K.B.; Wasson, M.C.; Farha, O.K. Porous materials for hydrogen storage. Chem 2022, 8, 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.W.; Langmi, H.W.; North, B.C.; Mathe, M. Review on processing of metal-organic framework (MOF) materials towards system integration for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Energy Res. 2015, 39, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, N.L.; Eckert, J.; Eddaoudi, M.; Vodak, D.T.; Kim, J.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Hydrogen storage in microporous metal-organic frameworks. Science 2003, 300, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Li, H.-P.; Yan, Q.-L. Advanced preparation and processing techniques for high energy fuel AlH3. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 129753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhu, M. AlH3 as a hydrogen storage material: Recent advances, prospects and challenges. Rare Met. 2021, 40, 3337–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabis, I.E.; Voyt, A.P.; Chernov, I.A.; Kuznetsov, V.G.; Baraban, A.P.; Elets, D.I.; Dobrotvorsky, M.A. Ultraviolet activation of thermal decomposition of α-alane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 14405–14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabis, I.E.; Elets, D.I.; Kuznetsov, V.G.; Baraban, A.P.; Dobrotvorskii, M.A.; Dobrotvorskii, A.M. Thermal- and photoactivation of aluminum hydride decomposition. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 86, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimo, S.; Nakamori, Y.; Kato, T.; Brown, C.; Jensen, C.M. Intrinsic and Mechanically Modified Thermal Stabilities of α-, β- and γ-Aluminum Trihydrides AlH3. Appl. Phys. A 2006, 83, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrock, G.; Reilly, J.; Graetz, J.; Zhou, W.-M.; Johnson, J.; Wegrzyn, J. Accelerated thermal decomposition of AlH3 for hydrogen-fueled vehicles. Appl. Phys. A 2005, 80, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, J.; Reilly, J.J. Decomposition kinetics of the AlH3 polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 22181–22185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-S.; Liu, H.-Z.; Qiu, N.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Zhao, G.-Y.; Xu, L.; Lan, Z.-Q.; Guo, J. Cycling hydrogen desorption properties and microstructures of MgH2–AlH3–NbF5 hydrogen storage materials. Rare Met. 2021, 40, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Yin, D.; Wang, L. Improvement of dehydrogenation performance by adding CeO2 to alpha-AlH3. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrock, G.; Reilly, J.; Graetz, J.; Zhou, W.-M.; Johnson, J.; Wegrzyn, J. Alkali Metal Hydride Doping of α-AlH3 for Enhanced H2 Desorption Kinetics. J. Alloys Compd. 2006, 421, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herley, P.J.; Christofferson, O.; Irwin, R. Decomposition of Alpha-Aluminum Hydride Powder. 1. Thermal Decomposition. J. Phys. Chem. 1981, 85, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herley, P.J.; Christofferson, O. Decomposition of Alpha-Aluminum Hydride Powder. 3. Simultaneous Photolytic-Thermal Decomposition. J. Phys. Chem. 1981, 85, 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herley, P.J.; Christofferson, O. Decomposition of Alpha-Aluminum Hydride Powder. 2. Photolytic Decomposition. J. Phys. Chem. 1981, 85, 1882–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, J.; Reilly, J.J.; Yartys, V.A.; Maehlen, J.P.; Bulychev, B.M.; Antonov, V.E.; Tarasov, B.P.; Gabis, I.E. Aluminum Hydride as a Hydrogen and Energy Storage Material: Past, Present and Future. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, S517–S528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Luo, H.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. MXene as a hydrogen storage material. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2025, 12, 031326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, A.; Zheng, J.-G.; Zhang, Q.-B.; Shu, Y.-G.; Yan, C.-G.; Zhang, L.-T.; Tao, Z.-L.; Chen, L.-X. Facile construction of MXene-supported niobium hydride nanoparticles toward reversible hydrogen storage in magnesium borohydride. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 4387–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Yang, Q.H.; Meng, X.Y.; Zhen, M.M.; Hu, Z.Z.; Shen, B.X. Research status and perspectives of MXene-based materials for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 1867–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Bontha, S.; Bishnoi, A.; Sharma, P. MXene as a hydrogen storage material? A review from fundamentals to practical applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Khan, S.A.; Mansha, M.; Iqbal, S.; Khan, M.; Abbas, S.M.; Ali, S. MXenes and MXene-based Metal Hydrides for Solid-State Hydrogen Storage: A Review. Chem. Asian J. 2024, 19, e202400308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzehlouy, A.; Soroush, M. MXene-based catalysts: A review. Mater. Today Catal. 2024, 5, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Ning, H.; Qing, P.; Huang, X.; Luo, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; et al. MXenes as catalysts for lightweight hydrogen storage materials: A review. Mater. Today Catal. 2024, 7, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Yang, J.; Wen, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Ding, S.; Ning, H.; Liu, H.; Jain, I.P.; Guo, J. An experimental and theoretical investigation of the enhanced effect of Ni atom-functionalized MXene composite on the mechanism for hydrogen storage performance in MgH2. J. Magnes. Alloys, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Sall, D.; Loupias, L.; Célérier, S.; Aouine, M.; Bargiela, P.; Prévot, M.; Morfin, F.; Piccolo, L. MXene-supported single-atom and nano catalysts for effective gas-phase hydrogenation reactions. Mater. Today Catal. 2023, 2, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hong, F.; Li, R.; Zhao, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, Z.; Qing, P.; Fan, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, J.; et al. Improved hydrogen storage properties of MgH2 by Mxene (Ti3C2) supported MnO2. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.-Q.; Li, G.-X.; Zhang, W.-H.; Luo, H.; Tang, H.-M.; Xu, L.; Sheng, P.; Wang, X.-H.; Huang, X.-T.; Huang, C.-K.; et al. Ti3AlCN MAX for tailoring MgH2 hydrogen storage material: From performance to mechanism. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 1923–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, L.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Ning, H.; Lan, Z.; Guo, J. Combinations of V2C and Ti3C2 MXenes for boosting the hydrogen storage performances of MgH2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 13235–13247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Initial Temperature (°C) | Capacity (wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| AlH3 + 2.5 wt% V2C | 122 | 2.2 |

| AlH3 + 2.5 wt% Nb2C | 95 | 9.0 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% V2C | 93 | 8.6 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% Ti3C2 | 130 | 2.6 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% Nb2C | 95 | 9.3 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% Ti3CN | 125 | 2.8 |

| Sample | Initial Temperature (°C) | Capacity (wt%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ar | Air | Ar | Air | |

| AlH3 + 2.5 wt%V2C | 122 | 125 | 2.2 | 8.4 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% V2C | 93 | 80 | 8.6 | 7.9 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% Nb2C | 95 | 120 | 9.3 | 8.7 |

| Sample | Initial Temperature (°C) | Capacity (wt%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 rpm | 350 rpm | 300 rpm | 350 rpm | |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% V2C | 93 | 137 | 8.6 | 3.8 |

| AlH3 + 1 wt% Nb2C | 95 | 90 | 9.3 | 8.7 |

| Al–H Bonds | Bond Length (Å) (Before) | Bond Length (Å) (After) |

|---|---|---|

| Al-H1 | 1.59379 | 1.71862 |

| Al-H2 | 1.59233 | 1.71890 |

| Al-H3 | 1.59379 | 1.71725 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ning, H.; Yang, Z.; Mao, J.; Luo, H.; Wei, Q.; Li, G.; Huang, C.; Lan, Z.; et al. Enhanced Hydrogen Desorption Performance of AlH3 via MXene Catalysis. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121143

He Z, Zhang L, Ning H, Yang Z, Mao J, Luo H, Wei Q, Li G, Huang C, Lan Z, et al. Enhanced Hydrogen Desorption Performance of AlH3 via MXene Catalysis. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121143

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhiling, Liang Zhang, Hua Ning, Zhicong Yang, Jiazheng Mao, Hui Luo, Qinqin Wei, Guangxu Li, Cunke Huang, Zhiqiang Lan, and et al. 2025. "Enhanced Hydrogen Desorption Performance of AlH3 via MXene Catalysis" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121143

APA StyleHe, Z., Zhang, L., Ning, H., Yang, Z., Mao, J., Luo, H., Wei, Q., Li, G., Huang, C., Lan, Z., Zhou, W., Guo, J., Wang, X., & Liu, H. (2025). Enhanced Hydrogen Desorption Performance of AlH3 via MXene Catalysis. Catalysts, 15(12), 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121143