Single TM−N4 Anchored on Topological Defective Graphene for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: A DFT Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

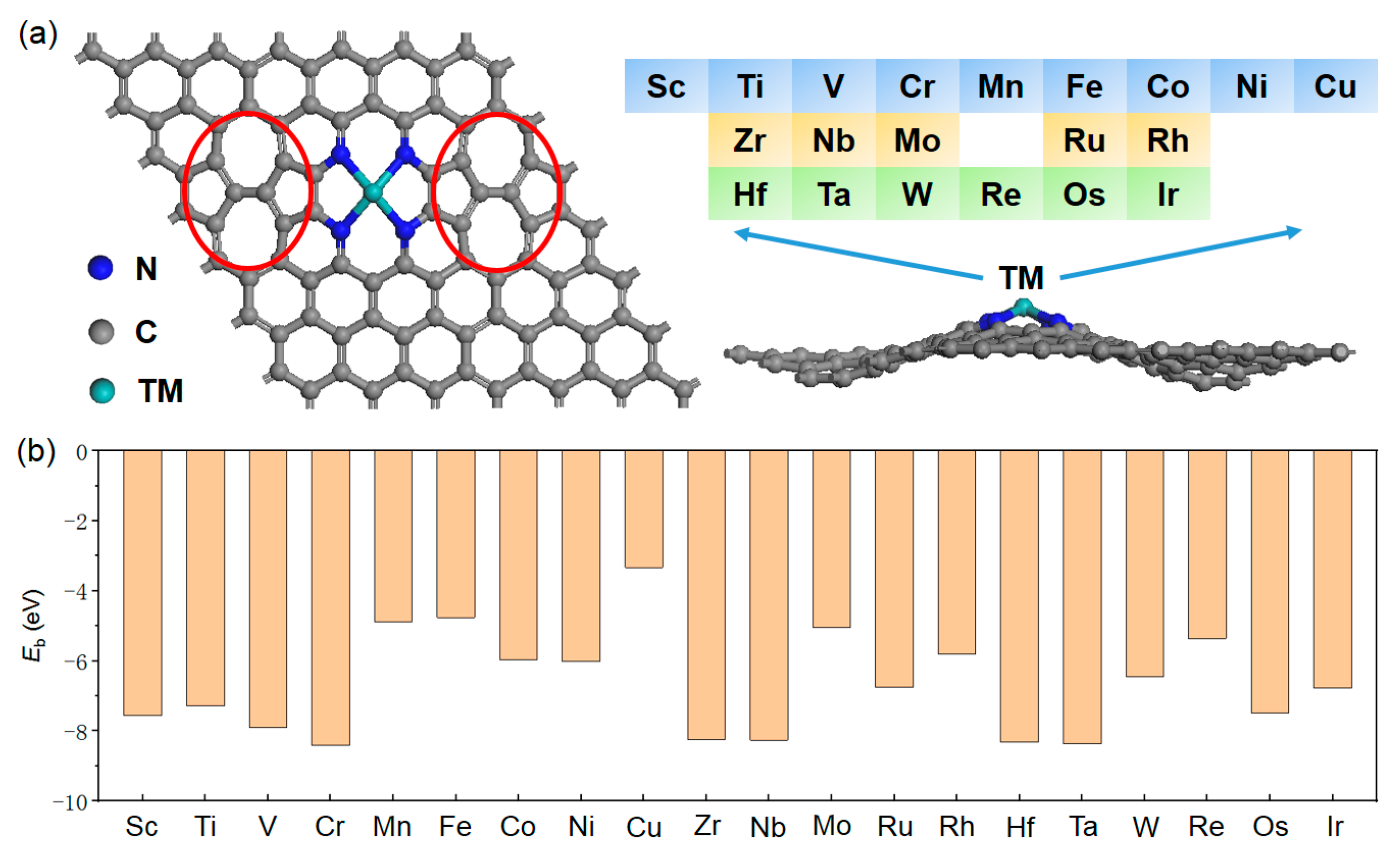

2.1. Structures and Binding

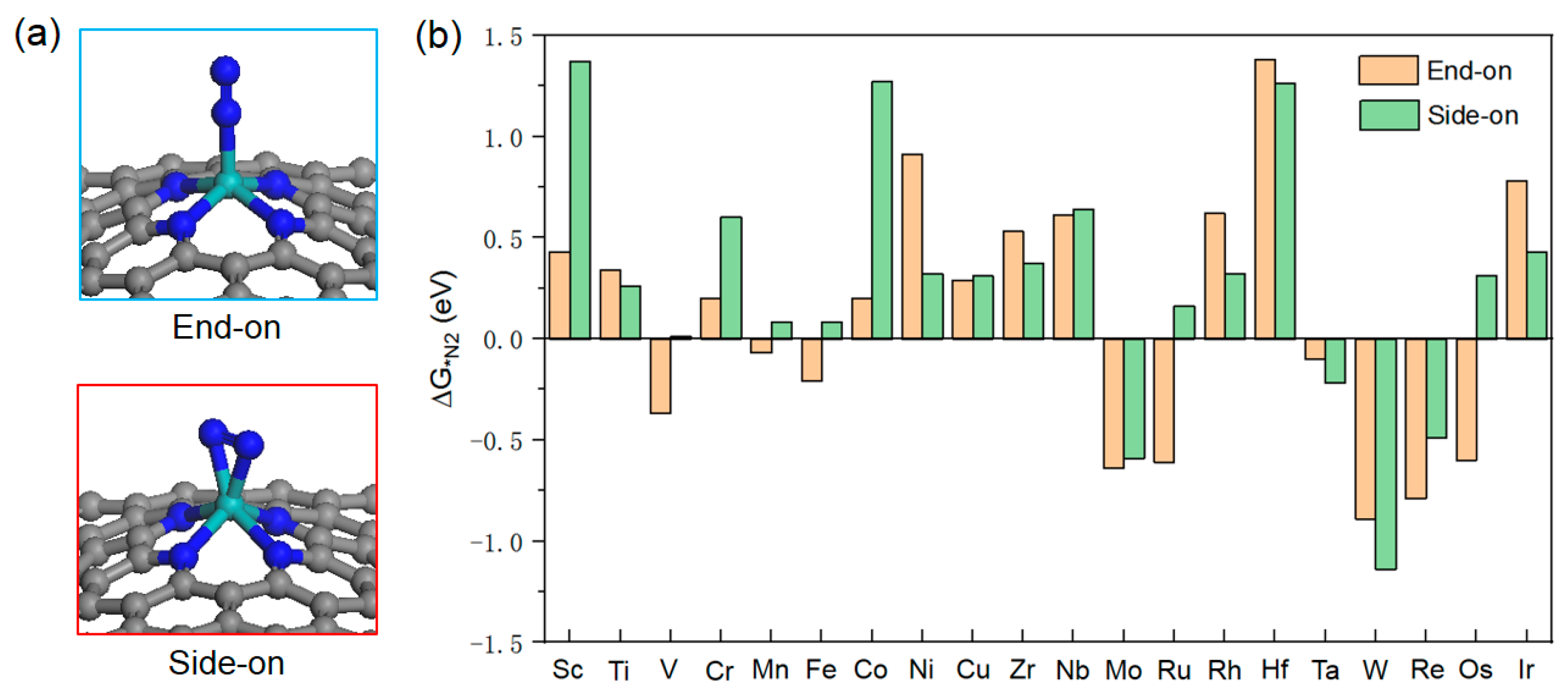

2.2. Catalyst Screening

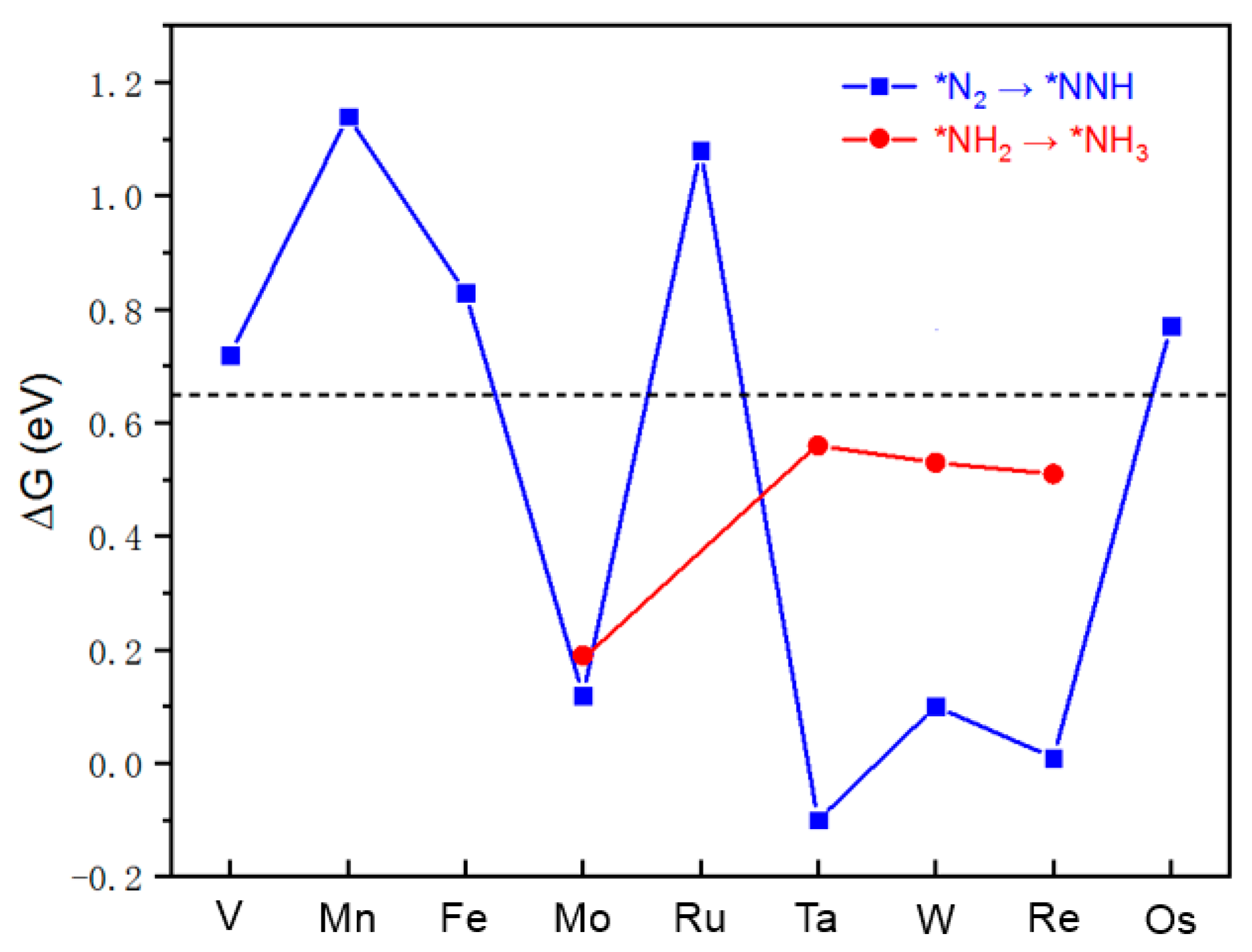

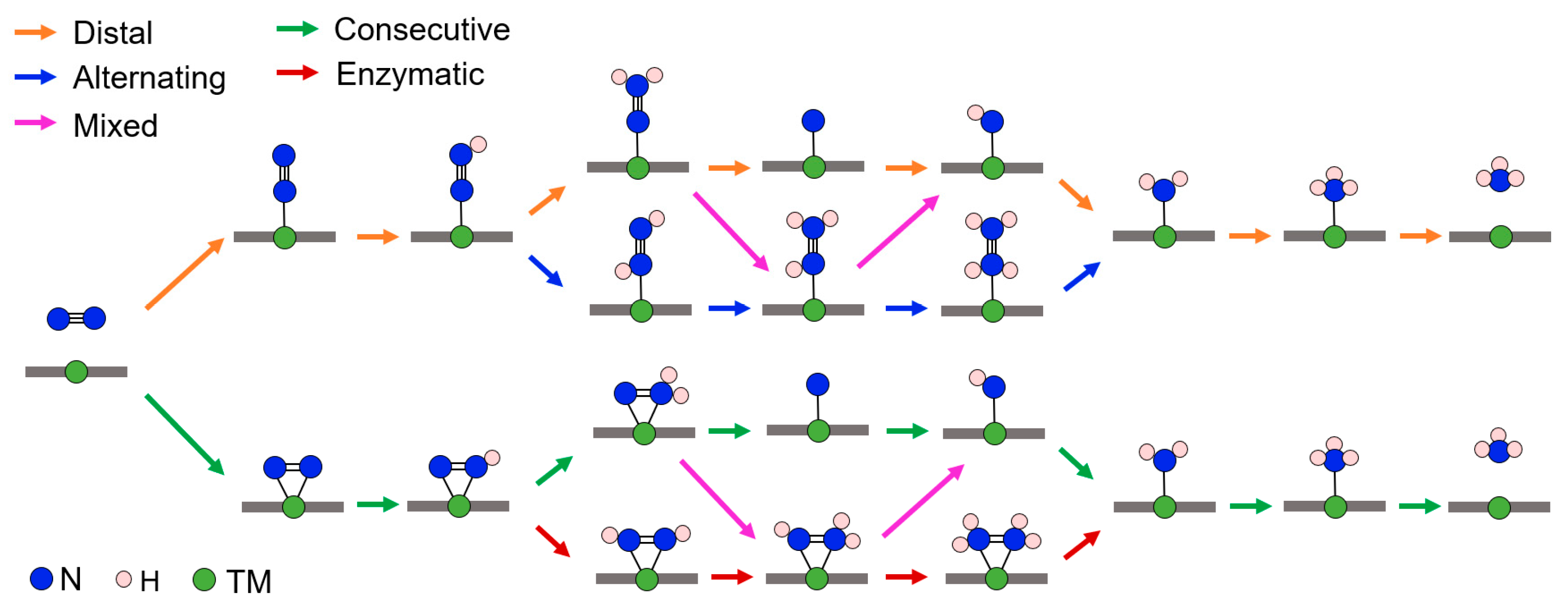

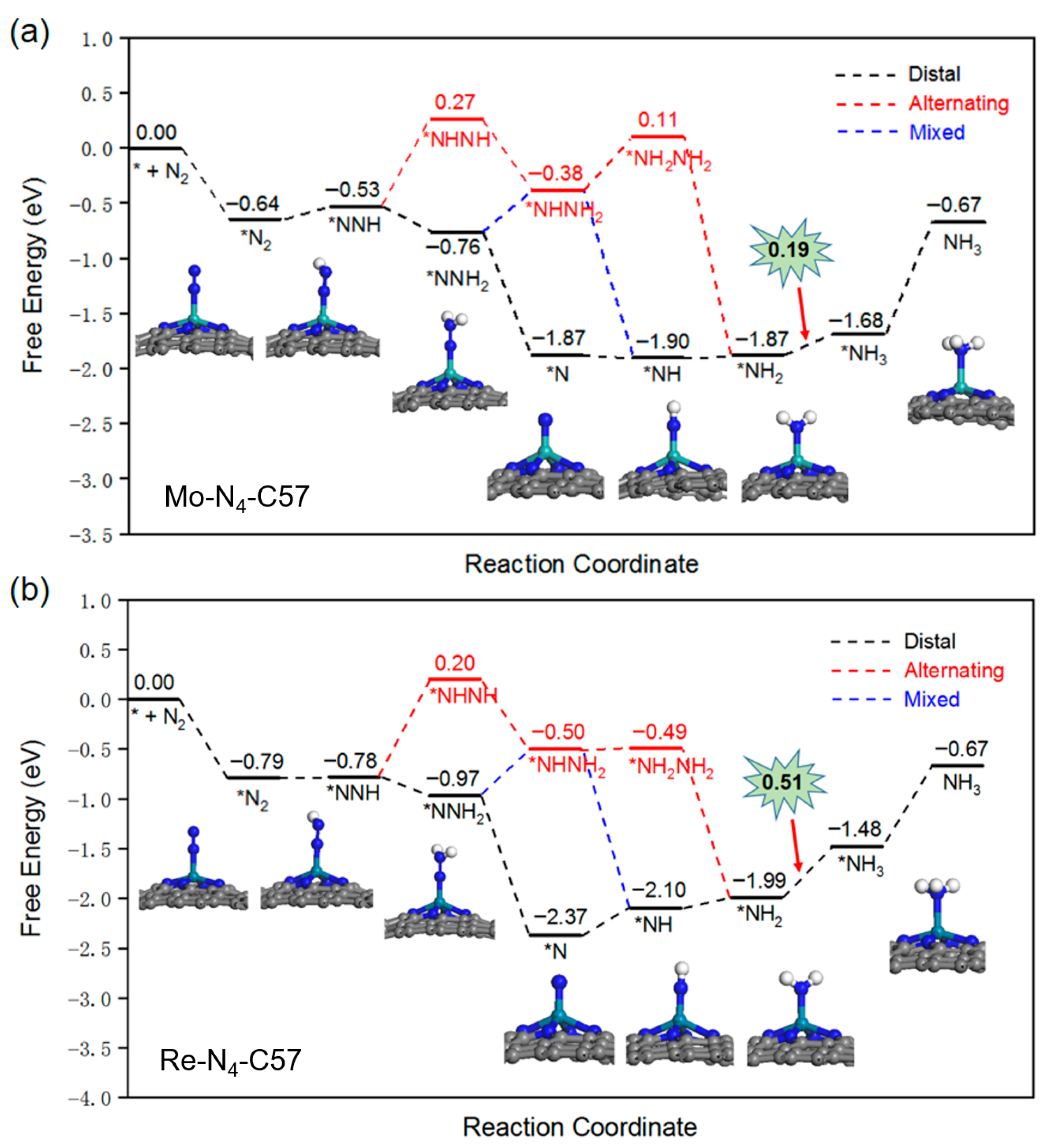

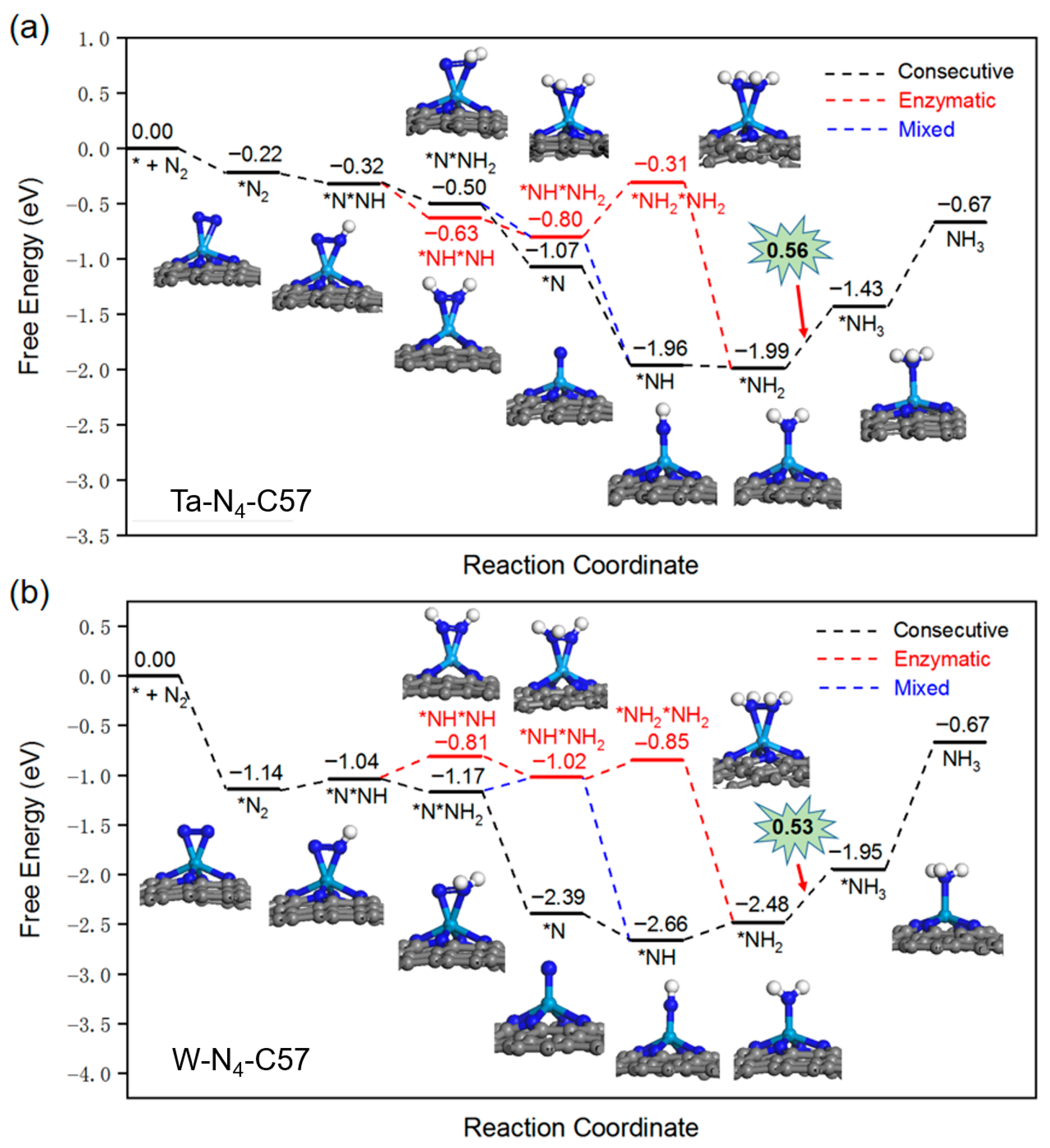

2.3. NRR Mechanism

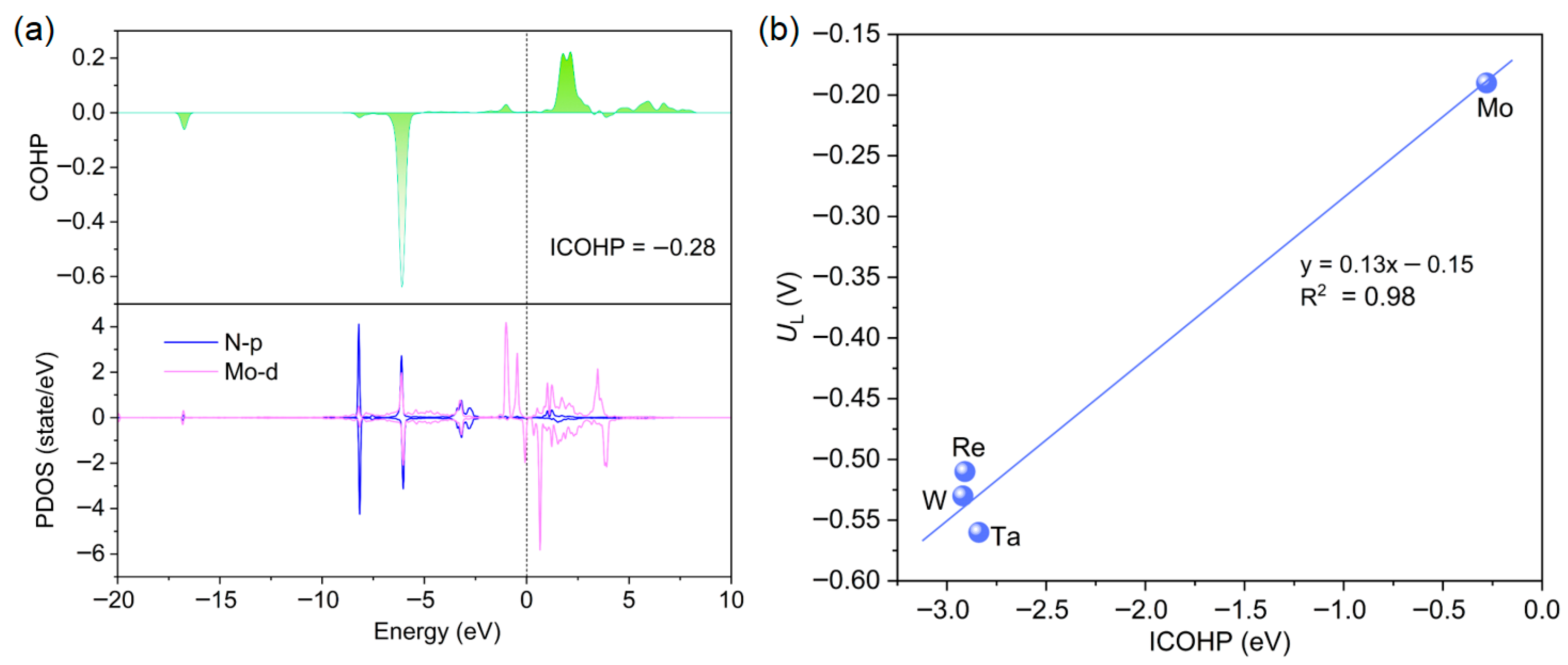

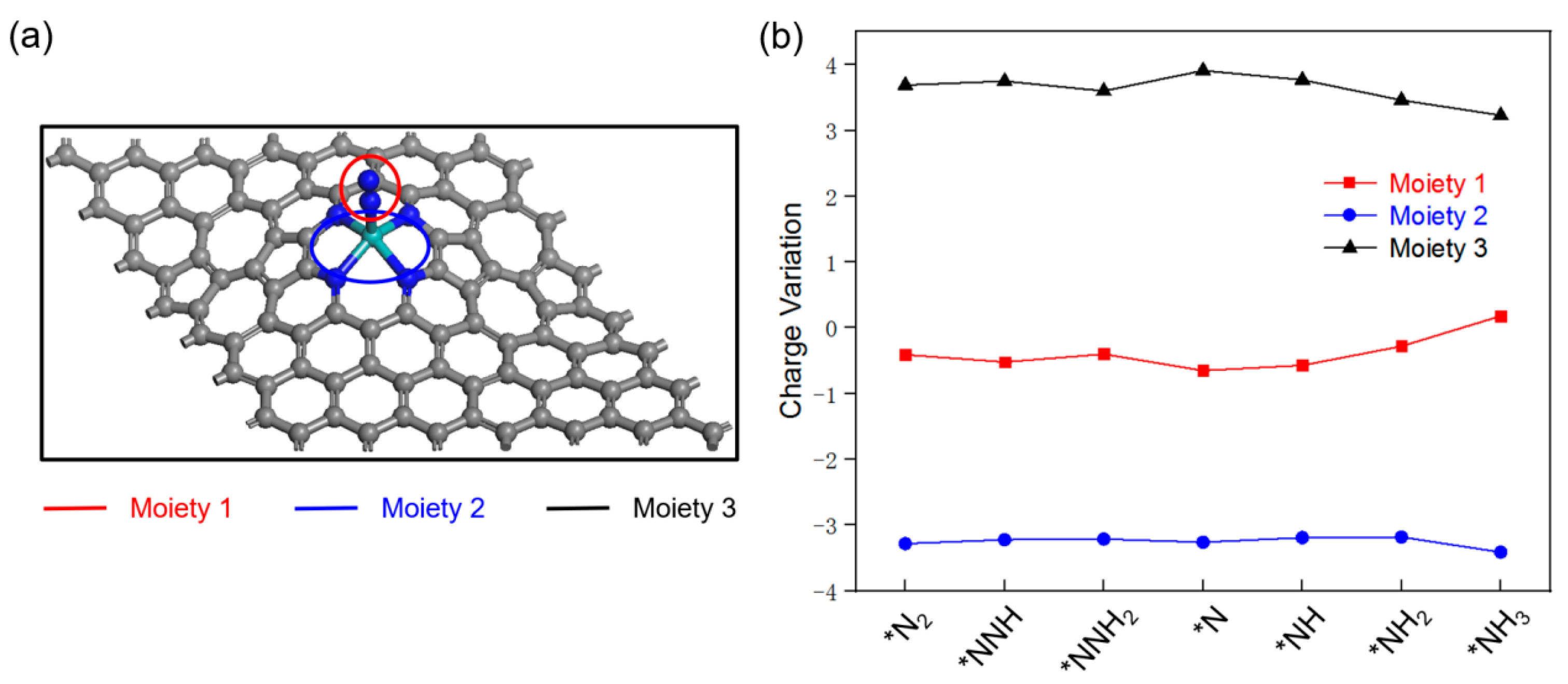

2.4. Origin of the NRR Activity

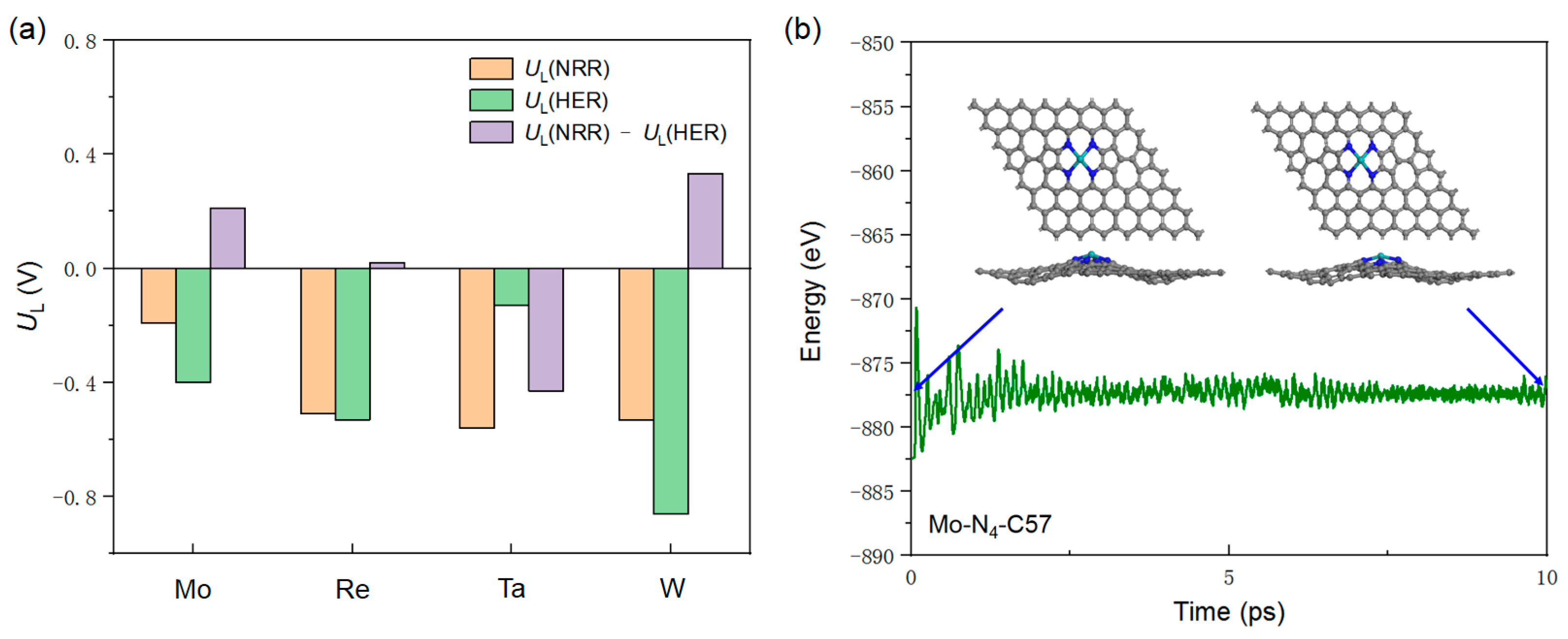

2.5. Selectivity and Stability

3. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coric, I.; Mercado, B.Q.; Bill, E.; Vinyard, D.J.; Holland, P.L. Binding of dinitrogen to an iron–sulfur–carbon site. Nature 2015, 526, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatzal, T.; Perez, K.A.; Einsle, O.; Howard, J.B.; Rees, D.C. Ligand binding to the FeMo-cofactor: Structures of CO–bound and reactivated nitrogenase. Science 2014, 345, 1620–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, D.R.; Cherepanov, P.V.; Choi, J.; Suryanto, B.H.R.; Hodgetts, R.Y.; Bakker, J.M.; Vallana, F.M.F.; Simonov, A.N. A roadmap to the ammonia economy. Joule 2020, 4, 1186–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M.; Kanbara, S.; Inoue, Y.; Kuganathan, N.; Sushko, P.V.; Yokoyama, T.; Hara, M.; Hosono, H. Electride support boosts nitrogen dissociation over ruthenium catalyst and shifts the bottleneck in ammonia synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Li, P.; Li, H.; Jiang, S.; Huang, H.; Sun, W.; Li, T.; Yu, H.; Li, K.; et al. Layer structured materials for ambient nitrogen fixation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 460, 214468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tan, X.; Jiang, K.; Zhai, S.; Li, Z. Atomic-level reactive sites for electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction to ammonia under ambient conditions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 489, 215196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.Y.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Q. A review of electrocatalytic reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia under ambient conditions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1800369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, M.; Du, X.; Ai, H.; Lo, H.K.; Wang, S.; Chen, S.; Xing, G.; Wang, X.; Pan, H. Development of Electrocatalysts for Efficient Nitrogen Reduction Reaction under Ambient Condition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrán, L.; Sancy, M.; Río, R.D.; Dalchiele, E.; Silva, D.; Veliz-Silva, D.F.; Isaacs, M. Review of Graphene Materials as Electrocatalysts for the Production of Green Ammonia from Nitrogen-Containing Compounds. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202500072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.R.; Rohr, B.A.; Schwalbe, J.A.; Cargnello, M.; Chan, K.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J.K. Electrochemical Ammonia Synthesis—The Selectivity Challenge. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 706–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minteer, S.D.; Christopher, P.; Linic, S. Recent Developments in Nitrogen Reduction Catalysts: A Virtual Issue. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ren, S.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, K.; Ding, L.; Wang, H. Advances in Electrocatalytic N2 Reduction—Strategies to Tackle the Selectivity Challenge. Small Methods 2019, 3, 1800337–1800356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanto, B.H.R.; Du, H.; Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Simonov, A.N.; MacFarlane, D.R. Challenges and Prospects in the Catalysis of Electroreduction of Nitrogen to Ammonia. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.R.; Rohr, B.A.; Statt, M.J.; Schwalbe, J.A.; Cargnello, M.; Nørskov, J.K. Strategies toward Selective Electrochemical Ammonia Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 8316–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Wang, A.; Yang, X.; Allard, L.F.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, T. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.L.; Dong, J.C.; Chen, D.L.; Hu, T.D.; Duan, X.D.; Shakir, I.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X.F. Single Atom Electrocatalysts Supported on Graphene or Graphene-Like Carbons. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 5207–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guan, J. Single-Atom Catalysts for Electrocatalytic Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.X.; Zheng, N.F. Coordination Chemistry of Atomically Dispersed Catalysts. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 636–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Cui, L.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, R.; Hao, H. DFT study the influence of active site structure on the electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction reaction. Fuel 2025, 380, 133174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xiao, C.; Ding, J.; Huang, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; Mitlin, D.; Hu, W. Review of Carbon Support Coordination Environments for Single Metal Atom Electrocatalysts (SACS). Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2301477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, F.X.; Wu, M.; Song, E.H.; Xiao, B.B.; Jiang, Q. Mo decoration on graphene edge for nitrogen fixation: A computational investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 568, 150867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, Y.; Dai, Z.; Shi, J. Boosting nitrogen reduction to ammonia on Fe-N3S sites by introduction S into defect graphene. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 25, 100954. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Xiao, B. ZrN6-Doped Graphene for Ammonia Synthesis: A Density Functional Theory Study. ChemPhysChem 2023, 24, e202200864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Z. Single Mo Atom Supported on Defective Boron Nitride Monolayer as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Nitrogen Fixation: A Computational Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12480–12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Meng, Y.; Xie, B.; Ni, Z.; Xia, S. Monatomic Ti doped on defective monolayer boron nitride as an electrocatalyst for the synthesis of ammonia: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 563, 150277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Guo, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Song, W. DFT calculations for transition metal atoms supported on BN as single-atom electrocatalysts for NH3 synthesis. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2025, 144, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafari, M.; Umer, M.; Nissimagoudar, A.S.; Anand, R.; Ha, M.; Umer, S.; Lee, G.; Kim, K.S. Unveiling the Role of Charge Transfer in Enhanced Electrochemical Nitrogen Fixation at Single-Atom Catalysts on BX Sheets (X = As, P, Sb). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 4530–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Q.; Gong, H.; Xue, M. Single Mo atom supported on defective BC2N monolayers as promising electrochemical catalysts for nitrogen reduction reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 149131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, T.; Yang, L.; Liu, R.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, J.; Luo, Y.; Lian, P.; Tang, S. Graphene–boron nitride hybrid-supported single Mo atom electrocatalysts for efficient nitrogen reduction reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 15173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-H.; Ma, Z.-W.; Wu, X.-W.; Chen, L.-K.; Sajid, Z.; Devasenathipathy, R.; Lin, J.-D.; Wu, D.-Y.; Tian, Z.-Q. Theoretical Insight into the Transition-Metal-Embedded Boron Nitride-Doped Graphene Single-Atom Catalysts for Electrochemical Nitrogen Reduction Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Guo, K.; Ye, D.; Gong, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, J. Asymmetric hydrogenation-driven enhancement of activity and selectivity in V-anchored N3-doped graphene catalysts for nitrogen reduction. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 162, 150787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Jiao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Davey, K.; Qiao, S.-Z. Tailoring Acidic Oxygen Reduction Selectivity on Single-Atom Catalysts via Modification of First and Second Coordination Spheres. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 7819–7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, N.; Xin, X.; Yu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zha, B.; Liu, W. Structure-activity relationship of defective electrocatalysts for nitrogen fixation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lei, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Defect engineering in earth-abundant electrocatalysts for CO2 and N2 reduction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Fu, C.; Li, Y.; Wei, H. Theoretical screening of single atoms anchored on defective graphene for electrocatalytic N2 reduction reactions: A DFT study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 9322–9329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Xie, C.; Wang, S.; Yao, X. Design and regulation of defective electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 10620–10659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Recent advances in the design of single-atom electrocatalysts by defect engineering. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1011597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Di, Y.; Liang, X.; Zeng, X.C. Atomically Dispersed Mo for Efficient Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: Nitrogen-Doped Defective Graphene Support. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 11632–11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, B.; Yan, L. Regulating the coordination environment of single-atom catalysts anchored on nitrogen-doped graphene for efficient nitrogen reduction. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Han, S.; Wu, P.; He, M.; Zhuang, X. Single Ru–N4 Site-Embedded Porous Carbons for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 13025–13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cui, Z.; Xiao, C.; Dai, W.; Lv, Y.; Li, Q.; Sa, R. Theoretical screening of efficient single-atom catalysts for nitrogen fixation based on a defective BN monolayer. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, L.; Hui, K.S.; Bin, F.; Zhou, W.; Fan, X.; Zalnezhad, E.; Li, J.; Hui, K.N. Computational Screening of Single Atoms Anchored on Defective Mo2CO2 MXene Nanosheet as Efficient Electrocatalysts for the Synthesis of Ammonia. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2021, 23, 2100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Gu, J.; Lin, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Huang, S. Tackling the Activity and Selectivity Challenges of Electrocatalysts toward the Nitrogen Reduction Reaction via Atomically Dispersed Biatom Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5709–5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skúlason, E.; Bligaard, T.; Gudmundsdóttir, S.; Studt, F.; Rossmeisl, J.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Vegge, T.; Jónsson, H.; Norskov, J.K. A theoretical evaluation of possible transition metal electro-catalysts for N2 reduction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Qian, C.; Zhou, S. Machine Learning Design of Single-Atom Catalysts for Nitrogen Fixation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 40656–40664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, T. Machine learning enabled rational design of atomic catalysts for electrochemical reactions. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Liang, X.; Ma, J. Automated Machine Learning of Interfacial Interaction Descriptors and Energies in Metal-Catalyzed N2 and CO2 Reduction Reactions. Langmuir 2025, 41, 3490–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, J.H.; Tsai, C.; Vojvodic, A.; Nørskov, J.K. The Challenge of Electrochemical Ammonia Synthesis: A New Perspective on the Role of Nitrogen Scaling Relations. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2180–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab Initio Molecular-Dynamics Simulation of the Liquid-Metal-Amorphous-Semiconductor Transition in Germanium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 14251–14269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmuller, J. Efficient Iterative Schemes for Ab Initio Total-Energy Calculations Using a Plane-Wave Basis Set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From Ultrasoft Pseudopotentials to the Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, K.; Sundararaman, R.; Letchworth-Weaver, K.; Arias, T.A.; Hennig, R.G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 084106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maintz, S.; Deringer, V.L.; Tchougréeff, A.L.; Dronskowski, R. LOBSTER: A Tool to Extract Chemical Bonding from Plane-Wave Based DFT. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckerman, M.; Laasonen, K.; Sprik, M.; Parrinello, M. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulation of the solvation and transport of hydronium and hydroxyl ions in water. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørskov, J.K.; Rossmeisl, J.; Logadottir, A.; Lindqvist, L.; Kitchin, J.R.; Bligaard, T.; Jónsson, H. Origin of the Overpotential for Oxygen Reduction at a Fuel-Cell Cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 17886–17892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Tang, G.; Chen, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, X. Qvasp: A Flexible Toolkit for VASP Users in Materials Simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2020, 257, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.-C.; Tang, G.; Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A User-Friendly Interface Facilitating High-Throughput Computing and Analysis Using VASP Code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 267, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuai, S.; Dong, H.; Duan, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, J. Single TM−N4 Anchored on Topological Defective Graphene for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: A DFT Study. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121135

Kuai S, Dong H, Duan X, Wang M, Liu J. Single TM−N4 Anchored on Topological Defective Graphene for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: A DFT Study. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121135

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuai, Shuxin, Haozhe Dong, Xuemei Duan, Meiyan Wang, and Jingyao Liu. 2025. "Single TM−N4 Anchored on Topological Defective Graphene for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: A DFT Study" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121135

APA StyleKuai, S., Dong, H., Duan, X., Wang, M., & Liu, J. (2025). Single TM−N4 Anchored on Topological Defective Graphene for Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Reduction: A DFT Study. Catalysts, 15(12), 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121135