Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Chinese Oil Shales for Enhanced Shale Oil Yield and Quality: A Kinetic and Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

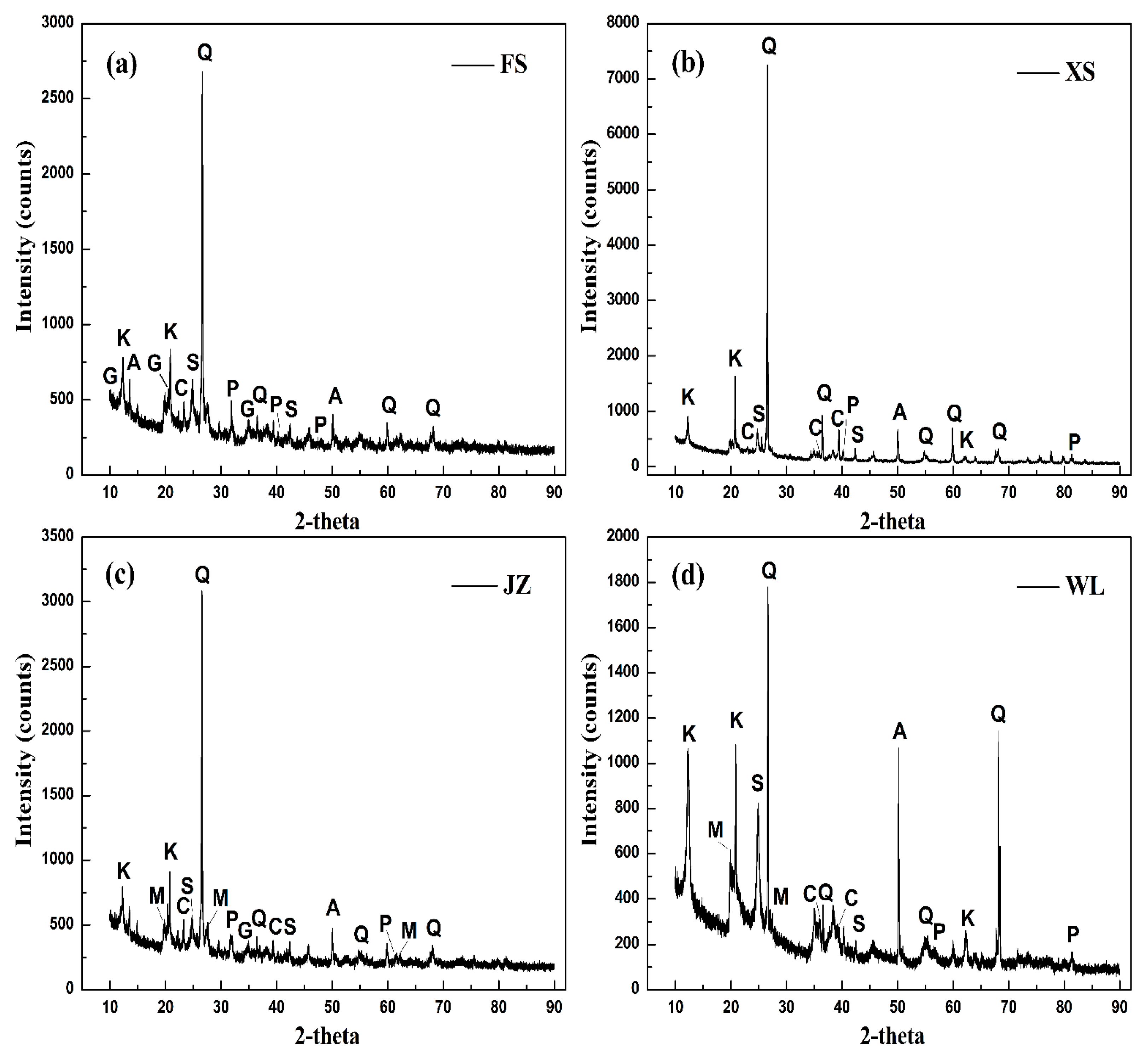

2.1. Oil Shale Characterisations

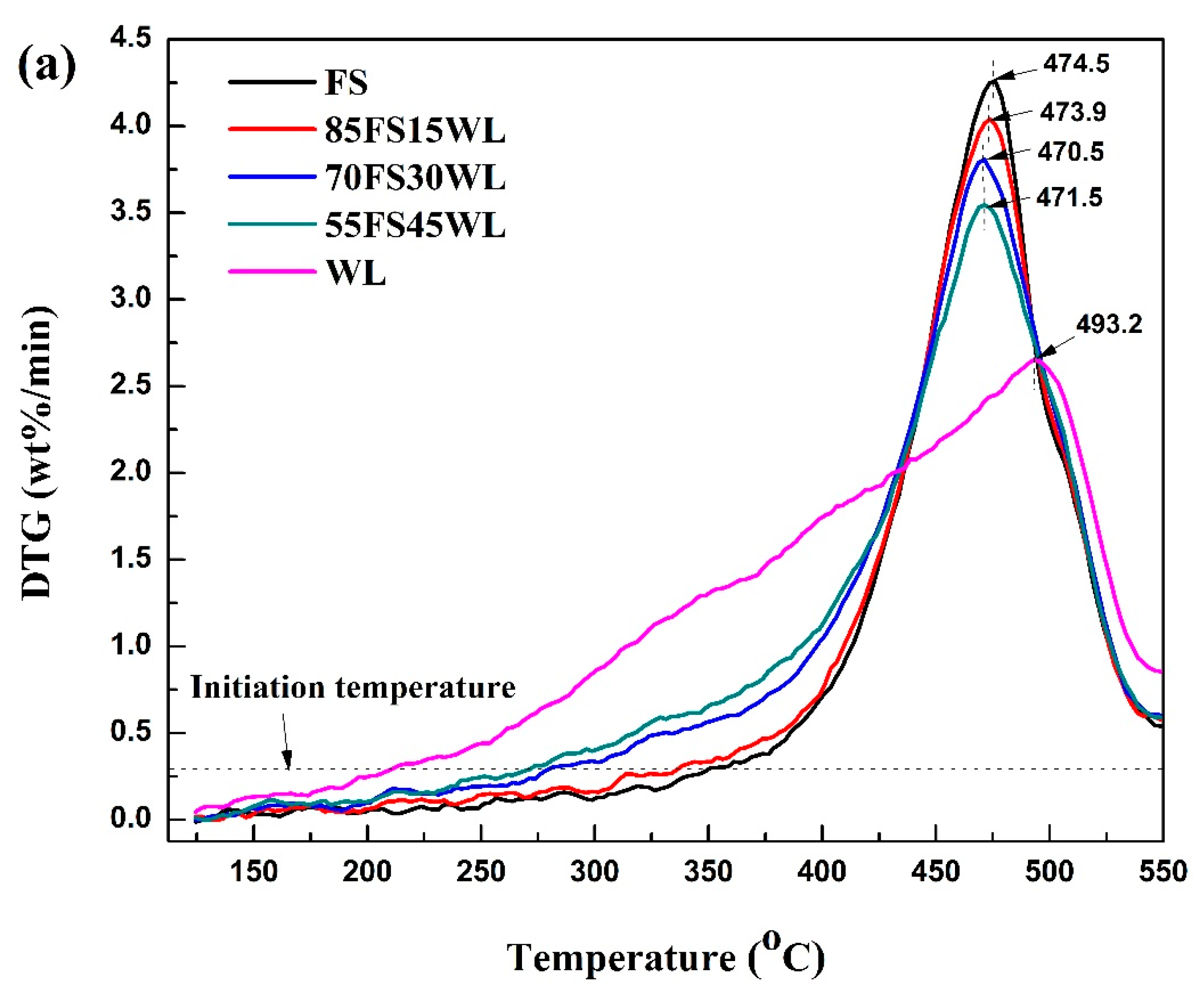

2.2. Pyrolysis Behaviours of Oil Shale and Their Blends Using TG Analysis

2.2.1. Pyrolysis Behaviours of Each Feedstock

2.2.2. Interactions Between the Selected Oil Shales at Different Blending Ratios

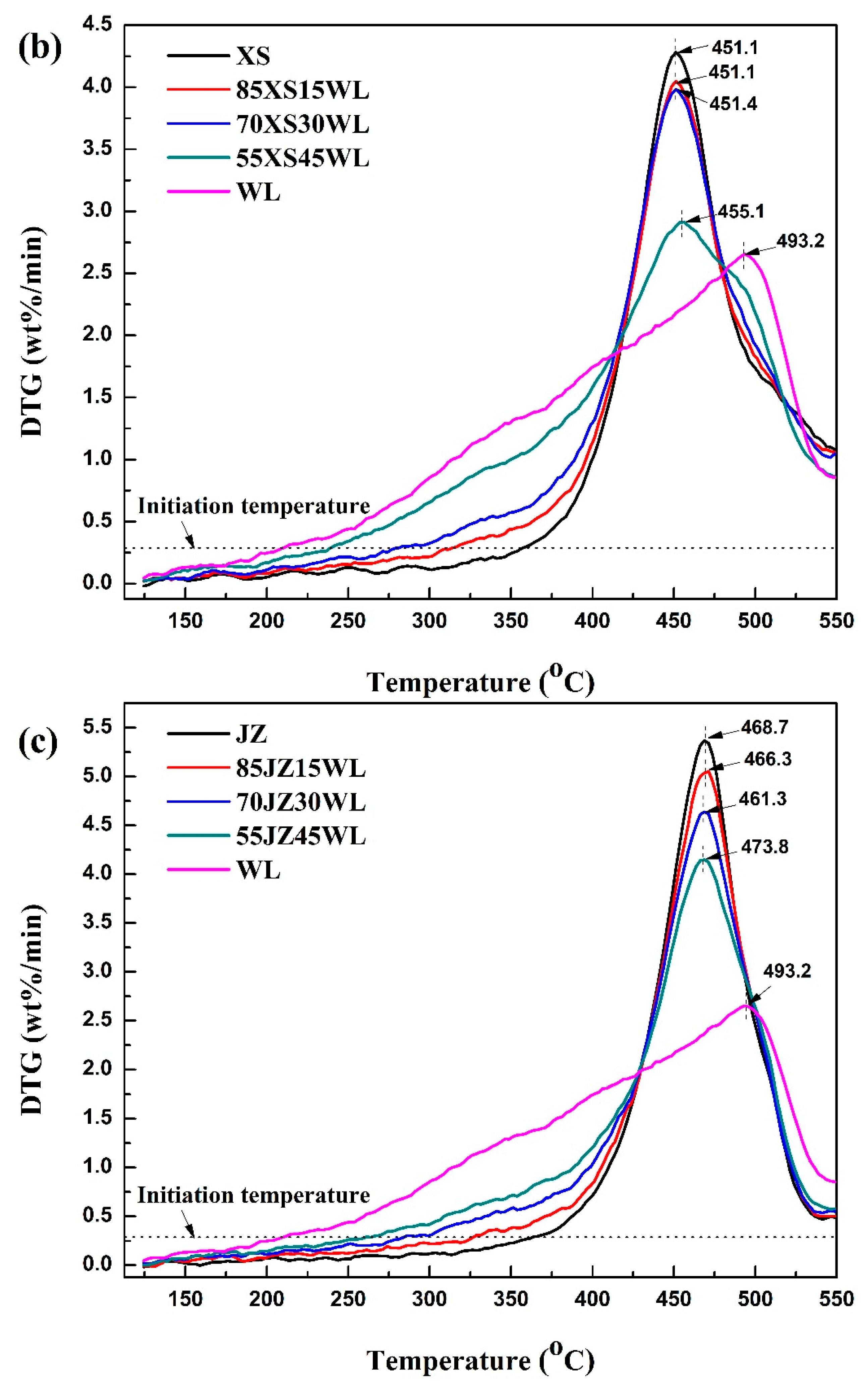

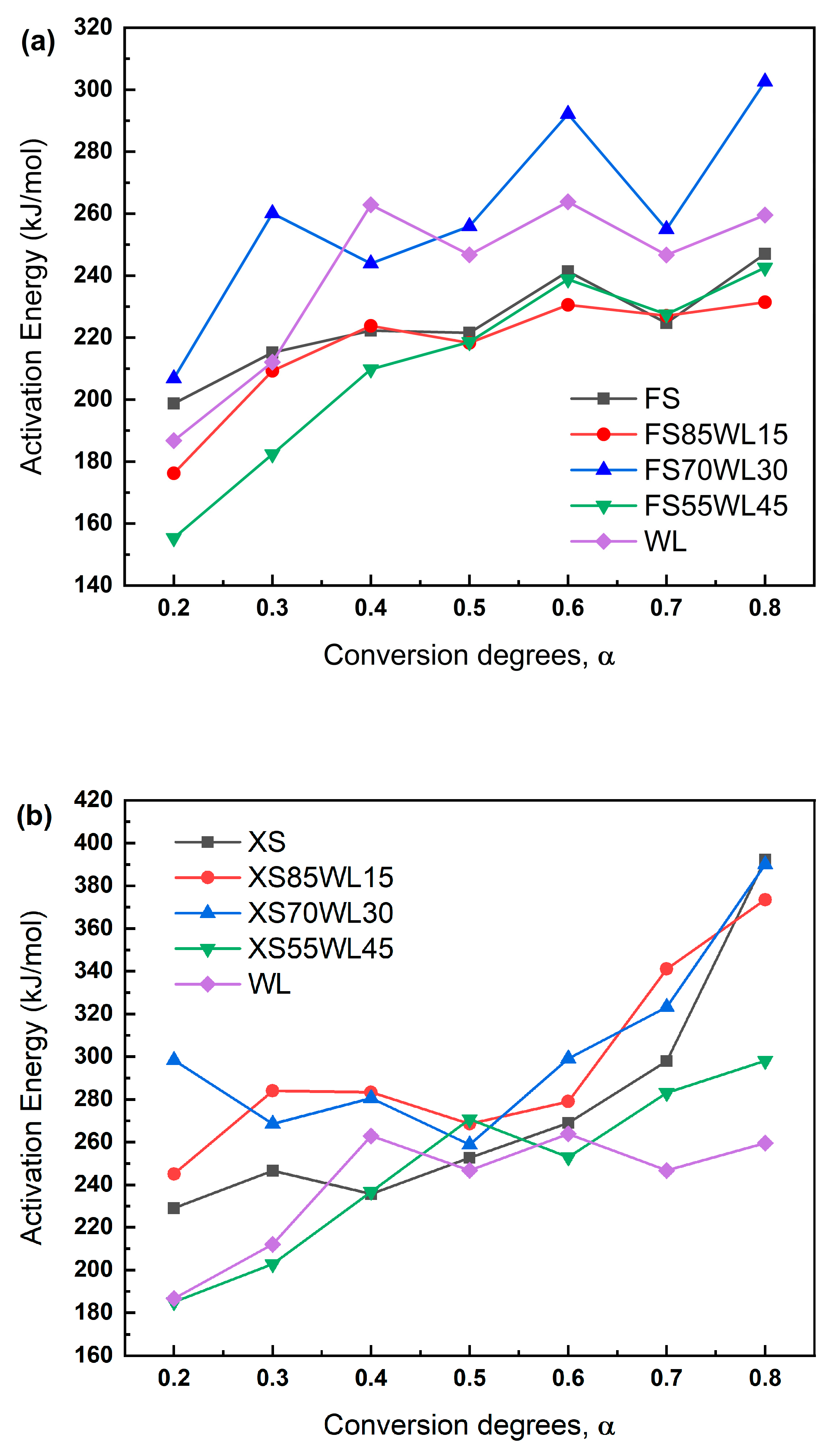

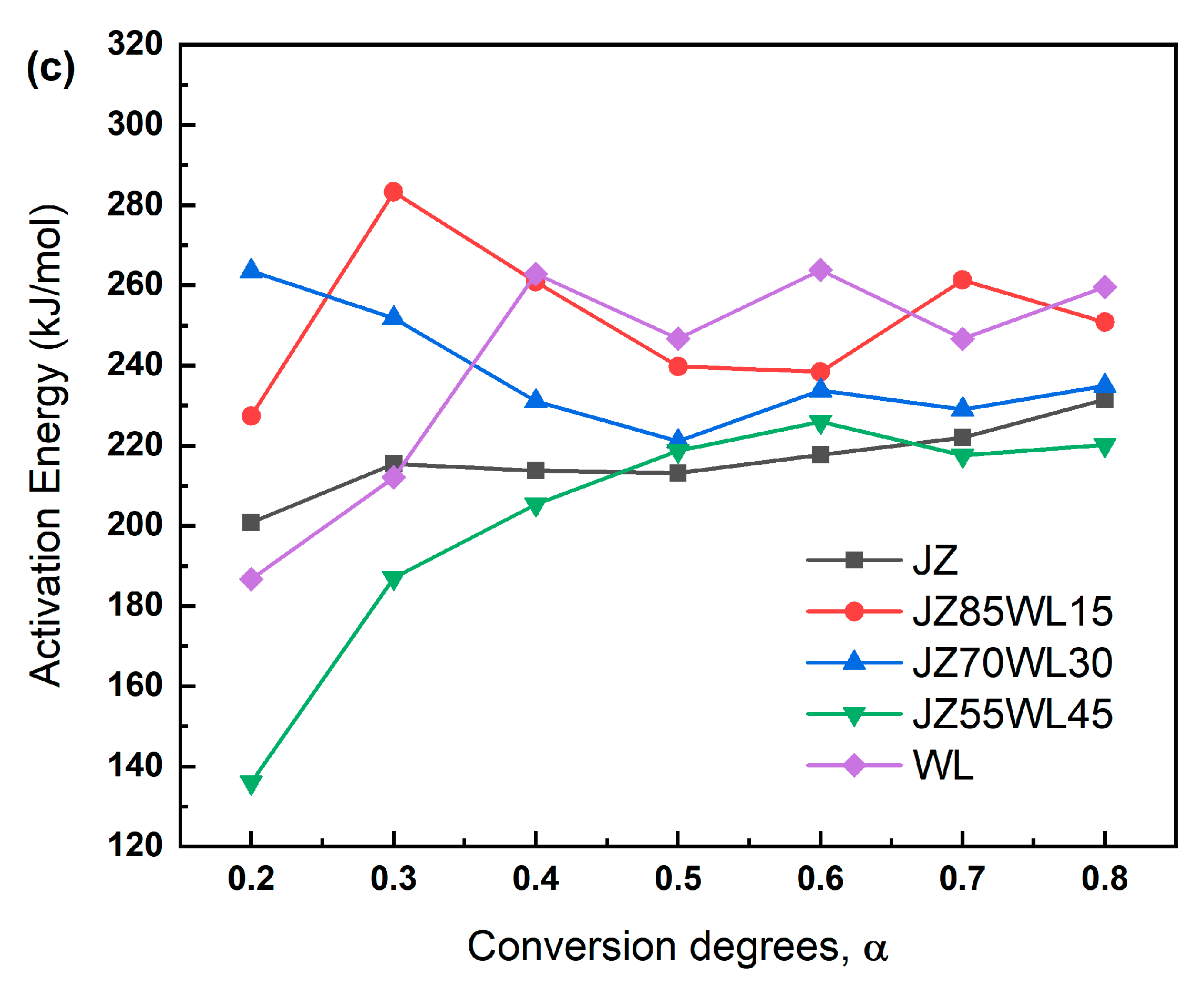

2.3. Kinetic Analysis

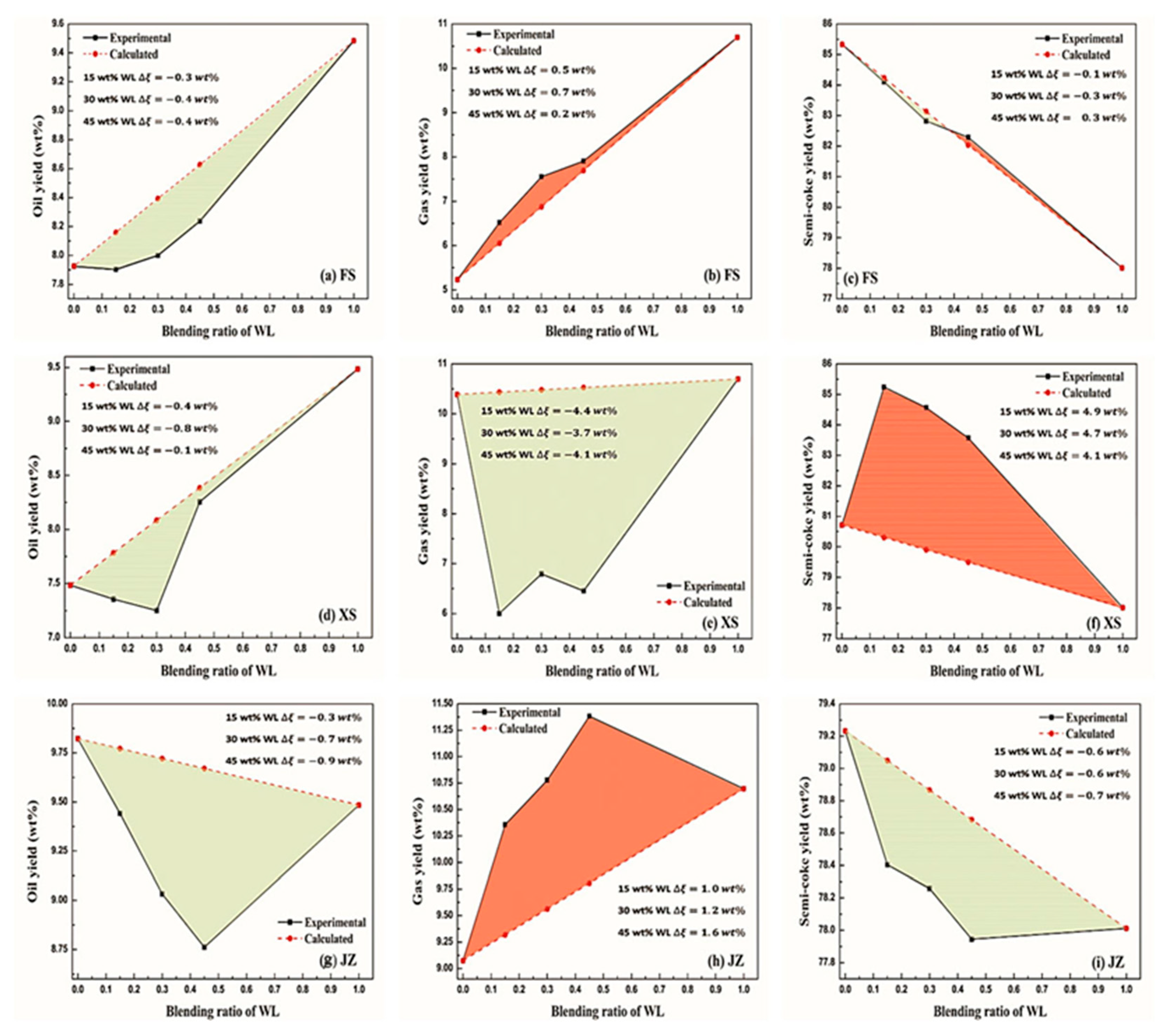

2.4. Effects of Oil Shale Blending on Product Distribution

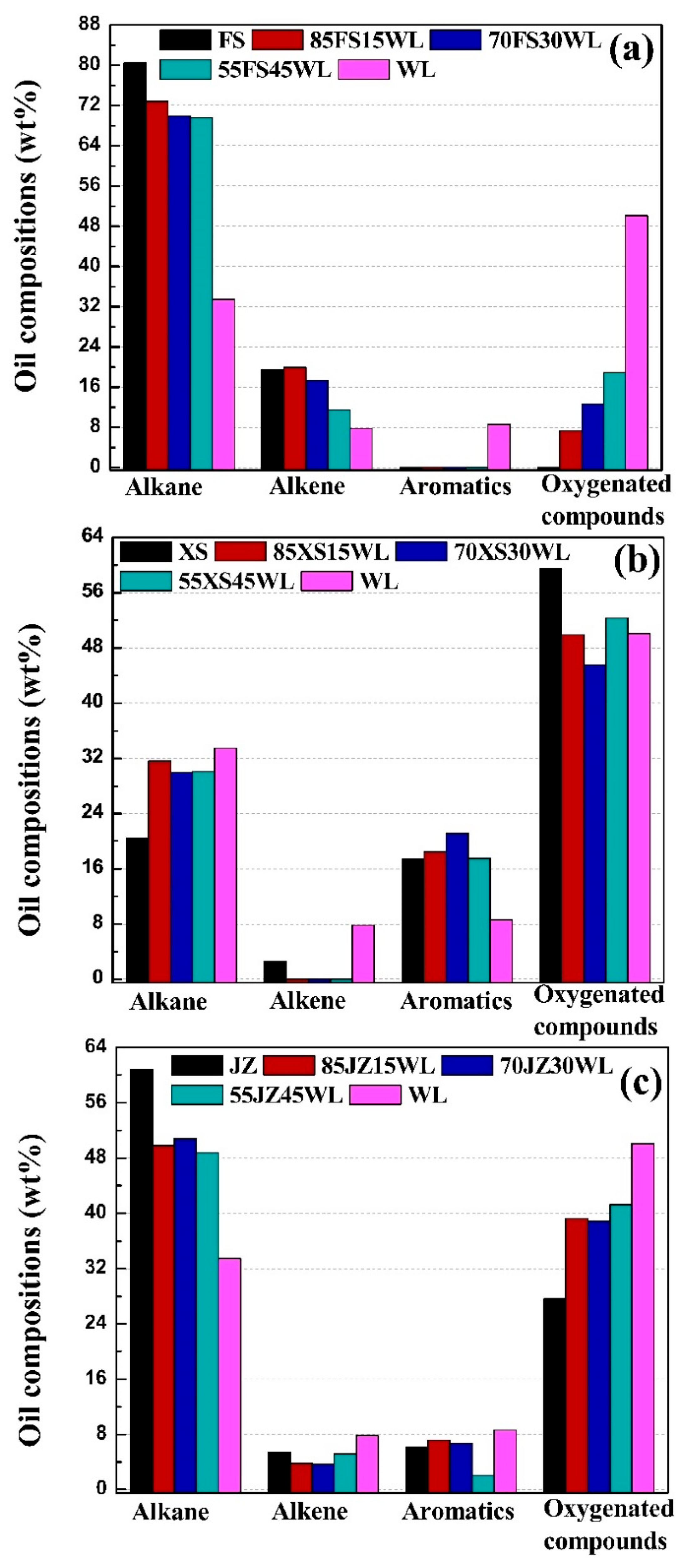

2.5. Effects of Oil Shale Blending on Shale Oil Compositions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Oil Shale and Preparation Method

3.2. Retorting Experiment

3.3. Characterisation

3.3.1. Oil Shale Characterisation

3.3.2. Shale Oil Characterisation

3.4. Evaluation of Pyrolysis Behaviour

3.5. Kinetic Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, M.; Oladejo, J.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. Investigation on breakage behaviour of oil shale with high grinding resistance: A comparison between microwave and conventional thermal processing. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2020, 151, 107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendow, K. Global oil shale issues and perspectives (Synthesis of the Symposium on Oil Shale held in Tallinn (Estonia) on 18 and 19 November 2002). Oil Shale 2003, 20, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Wang, X.; Quan, C.; Wu, C. Study of oily sludge pyrolysis combined with fine particle removal using a ceramic membrane in a fixed-bed reactor. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2018, 128, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Chu, M.; Zhang, C.; Bai, S.; Lin, H.; Ma, L. Compositional and structural variations of bitumen and its interactions with mineral matters during Huadian oil shale pyrolysis. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 3111–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Han, X.; Jiang, X. Characterization of Dachengzi oil shale fast pyrolysis by curie-point pyrolysis-GC-MS. Oil Shale 2015, 32, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Han, X.; Jiang, X. Interactions between oil shale and hydrogen-rich wastes during co-pyrolysis: 1. Co-pyrolysis of oil shale and polyolefins. Fuel 2020, 265, 116994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Chishti, H. Reaction of nitrogen and sulphur compounds during catalytic hydrotreatment of shale oil. Fuel 2001, 80, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, K. CO2 gasification performance and alkali/alkaline earth metals catalytic mechanism of Zhundong coal char. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Jia, F.; Guo, C.; Pan, H.; Long, X.; Liu, G. Effect of Shale Ash-Based Catalyst on the Pyrolysis of Fushun Oil Shale. Catalysts 2019, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Song, L.; Jiang, X. Catalytic Effects of Fe- and Ca-Based Additives on Gas Evolution During Pyrolysis Of Dachengzi Oil Shale of China. Oil Shale 2018, 35, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Bai, S.; Lin, H.; Ma, L. Investigation of the effect of selected transition metal salts on the pyrolysis of Huadian oil shale, China. Oil Shale 2017, 34, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, H.W.; Jang, S.H.; Jeong, J.; Ryu, S.; Jung, S.-C.; Park, Y.-K. Production of biofuels from pine needle via catalytic fast pyrolysis over HBeta. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 37, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M.; Song, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Effect of calcite, kaolinite, gypsum, and montmorillonite on Huadian oil shale kerogen pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, R.; Jin, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, H. Effect of inherent and additional pyrite on the pyrolysis behavior of oil shale. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 105, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Song, L.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Li, J. Influence of pyrolysis condition and transition metal salt on the product yield and characterization via Huadian oil shale pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zheng, G.; Sajjad, W.; Xu, W.; Fan, Q.; Zheng, J.; Xia, Y. Influence of minerals and iron on natural gases generation during pyrolysis of type-III kerogen. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 89, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chi, M.; Cui, D.; XU, X. Effect of smectite on the pyrolysis of kerogen isolated from oil shale. Chem. Ind. Eng. Prog. 2016, 20, 766. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Hong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Ding, H. Behavior, kinetic and product characteristics of the pyrolysis of oil shale catalyzed by cobalt-montmorillonite catalyst. Fuel 2020, 269, 117468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Deng, S.; Sun, Y. Studies on the co-pyrolysis characteristics of oil shale and spent oil shale. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 123, 1707–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, X. Catalytic effects of shale ash with different particle sizes on characteristics of gas evolution from retorting oil shale. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wu, X.; Sharmin, N.; Zhao, H.; Lester, E.; Wu, T.; Pang, C.H. Synthesis and functionalization of cauliflower-like mesoporous siliceous foam materials from oil shale waste for post-combustion carbon capture. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 40, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsin, G.; Kılıç, M.; Apaydin-Varol, E.; Pütün, A.E.; Pütün, E. A thermo-kinetic study on co-pyrolysis of oil shale and polyethylene terephthalate using TGA/FT-IR. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 37, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liao, Y.; Yu, Z.; Fang, S.; Lin, Y.; Fan, Y.; Peng, X.; Ma, X. Co-pyrolysis kinetics of sewage sludge and oil shale thermal decomposition using TGA–FTIR analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 118, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Yu, Z.; Fang, S.; Ma, X. Behaviors, product characteristics and kinetics of catalytic co-pyrolysis spirulina and oil shale. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 192, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulkas, A.; Makayssi, T.; Bilali, L.; Nadifiyine, M.; Benchanaa, M. Co-pyrolysis of oil shale and High density polyethylene: Structural characterization of the oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 96, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, P.A.; Tosun, O.; Canel, M. The synergistic effect of co-pyrolysis of oil shale and low density polyethylene mixtures and characterization of pyrolysis liquid. J. Energy Inst. 2017, 90, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Han, X.; Mu, M.; Jiang, X. Studies of the co-pyrolysis of oil shale and wheat straw. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 6941–6950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.H.; Wall, L.A. A quick, direct method for the determination of activation energy from thermogravimetric data. J. Polym. Sci. Part B 1966, 4, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction kinetics in differential thermal analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1702–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W. Specific gravity-oil yield relationships of two colorado oil-shale cores. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1956, 48, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-R.; Han, X.-X.; Jiang, X.-M. Comparison of fast pyrolysis characteristics of Huadian oil shales from different mines using Curie-point pyrolysis-GC/MS. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 128, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Chu, M.; Zhang, C.; Bai, S.; Lin, H.; Ma, L. Influence of inherent mineral matrix on the product yield and characterization from Huadian oil shale pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 130, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espitalié, J.; Makadi, K.S.; Trichet, J. Role of the mineral matrix during kerogen pyrolysis. Org. Geochem. 1984, 6, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oja, V.; Elenurm, A.; Rohtla, I.; Tali, E.; Tearo, E.; Yanchilin, A. Comparison of oil shales from different deposits: Oil shale pyrolysis and co-pyrolysis with ash. Oil Shale 2007, 24, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harahsheh, M.; Al-Ayed, O.; Robinson, J.; Kingman, S.; Al-Harahsheh, A.; Tarawneh, K.; Saeid, A.; Barranco, R. Effect of demineralization and heating rate on the pyrolysis kinetics of Jordanian oil shales. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 1805–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.T.; Chishti, H.M. Two stage pyrolysis of oil shale using a zeolite catalyst. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2000, 55, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Investigation on the catalytic effect of AAEMs on the pyrolysis characteristics of Changji oil shale and its kinetics. Fuel 2020, 267, 117287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.T.; Ahmad, N. Investigation of oil-shale pyrolysis processing conditions using thermogravimetric analysis. Appl. Energy 2000, 66, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Guo, W.; Lü, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, Q.; Sun, Y. Kinetic study on the pyrolysis behavior of Huadian oil shale via non-isothermal thermogravimetric data. Fuel 2015, 146, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulkas, A.; El Harfi, K. Study of the Kinetics and Mechanisms of Thermal Decomposition of Moroccan Tarfaya Oil Shale and Its Kerogen. Oil Shale 2008, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Chen, Z.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, S.; Xu, G. Secondary cracking and upgrading of shale oil from pyrolyzing oil shale over shale ash. Energy Fuels 2015, 29, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Han, X.; Tong, J. Effect of Residence Time on Products Yield and Characteristics of Shale Oil and Gases Produced by Low-Temperature Retorting of Dachengzi Oil Shale. Oil Shale 2013, 30, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M. Evaluation of the porous structure of Huadian oil shale during pyrolysis using multiple approaches. Fuel 2017, 187, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Sun, L.; Xu, B.; He, L.; Xiang, J. Effects of inherent alkali and alkaline earth metallic species on biomass pyrolysis at different temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 192, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janković, B. The kinetic modeling of the non-isothermal pyrolysis of Brazilian oil shale: Application of the Weibull probability mixture model. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 111, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Sun, Y.; Guo, W.; Deng, S.; Hou, C.; Qu, L.; Li, Q. Non-isothermal thermogravimetric analysis of pyrolysis kinetics of four oil shales using Sestak–Berggren method. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 135, 2287–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yue, C. Study of pyrolysis kinetics of oil shale. Fuel 2003, 82, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ju, Y.; Lammers, L.; Kulasinski, K.; Zheng, L. Tortuosity of kerogen pore structure to gas diffusion at molecular-and nano-scales: A molecular dynamics simulation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 215, 115460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weck, P.F.; Kim, E.; Wang, Y.; Kruichak, J.N.; Mills, M.M.; Matteo, E.N.; Pellenq, R.J.-M. Model representations of kerogen structures: An insight from density functional theory calculations and spectroscopic measurements. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Külaots, I.; Goldfarb, J.L.; Suuberg, E.M. Characterization of Chinese, American and Estonian oil shale semicokes and their sorptive potential. Fuel 2010, 89, 3300–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ayed, O.S.; Matouq, M.; Anbar, Z.; Khaleel, A.M.; Abu-Nameh, E. Oil shale pyrolysis kinetics and variable activation energy principle. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Sun, G.; Xie, W.; Kuo, J.; Li, S.; Liang, J.; Chang, K.; Sun, S.; Buyukada, M. Thermogravimetric analysis of (co-) combustion of oily sludge and litchi peels: Combustion characterization, interactions and kinetics. Thermochim. Acta 2018, 667, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Qudaih, R.; Talab, I.; Janajreh, I. Kinetics of pyrolysis and combustion of oil shale sample from thermogravimetric data. Fuel 2011, 90, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, W.; Hongpeng, L.; Baizhong, S.; Shaohua, L. Study on Pyrolysis Characteristics of Huadian Oil Shale With Isoconversional Method. Oil Shale 2009, 26, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Bai, J.; Sun, B.; Sun, J. Comprehensive utilization strategy of Huandian oil shale. Oil Shale 2005, 22, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, I.; Galikova, L. Mechanism of the H 2 O (g) release during a dehydroxylation of montmorillonite. Chem. Pap. 1979, 33, 604–611. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Harahsheh, M.; Shawabkeh, R.; Al-Harahsheh, A.; Tarawneh, K.; Batiha, M.M. Surface modification and characterization of Jordanian kaolinite: Application for lead removal from aqueous solutions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8098–8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, K.; Madsen, F.T.; Kahr, G. Dehydroxylation behavior of heat-treated and steam-treated homoionic cis-vacant montmorillonites. Clays Clay Miner. 1999, 47, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, J.M. Influence of heating rate on the pyrolysis of Jordan oil shale. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2002, 62, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, A.K. Chemistry of Shale Oil Cracking; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kotrel, S.; Knözinger, H.; Gates, B. The Haag–Dessau mechanism of protolytic cracking of alkanes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2000, 35, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.X.; Jiang, X.M.; Cui, Z.G. Studies of the effect of retorting factors on the yield of shale oil for a new comprehensive utilization technology of oil shale. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 2381–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Chrissafis, K.; Di Lorenzo, M.L.; Koga, N.; Pijolat, M.; Roduit, B.; Sbirrazzuoli, N.; Suñol, J.J. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for collecting experimental thermal analysis data for kinetic computations. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 590, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladejo, J.M.; Adegbite, S.; Pang, C.H.; Liu, H.; Parvez, A.M.; Wu, T. A novel index for the study of synergistic effects during the co-processing of coal and biomass. Appl. Energy 2017, 188, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-g.; Cheng, B.; Si, Y.-b.; Cao, D.-j.; Jiang, H.-y.; Han, G.-m.; Liu, X.-h. Thermal decomposition kinetics and characteristics of Spartina alterniflora via thermogravimetric analysis. Renew. Energy 2014, 68, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Chang, K.; Kuo, J.; He, Y.; Sun, J.; Zheng, L.; Xie, W. Assessing thermal behaviors and kinetics of (co-) combustion of textile dyeing sludge and sugarcane bagasse. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 131, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Huang, L.; Sun, S.; Sun, J.; Chang, K.; Kuo, J.; Huang, S.; Ning, X. Investigation of co-combustion characteristics of sewage sludge and coffee grounds mixtures using thermogravimetric analysis coupled to artificial neural networks modeling. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, A.W.; Redfern, J. Kinetic parameters from thermogravimetric data. Nature 1964, 201, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Wight, C.A. Model-free and model-fitting approaches to kinetic analysis of isothermal and nonisothermal data. Thermochim. Acta 1999, 340–341, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Q.; Ren, S.; Kong, M. Evaluation of biochar combustion reactivity under pyrolysis temperature: Microstructure characterization, kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 1914–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Q.; Xia, Y.; Liao, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Huang, Y. Facile synthesis of hydrotalcite and its thermal decomposition kinetics mechanism study with masterplots method. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 579, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, N.; Criado, J.M. Kinetic Analyses of Solid-State Reactions with a Particle-Size Distribution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1998, 81, 2901–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FS | XS | JZ | WL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 3.36 | 1.40 | 3.20 | 5.11 |

| Volatiles | 15.59 | 16.03 | 22.47 | 27.32 |

| Fixed carbon | 1.92 | 15.25 | 6.31 | 15.55 |

| Ash | 79.13 | 67.32 | 68.02 | 52.02 |

| C | 54.20 | 62.38 | 42.11 | 66.74 |

| H | 11.25 | 4.29 | 7.54 | 8.17 |

| N | 4.17 | 1.86 | 3.63 | 2.05 |

| S | 3.12 | 1.22 | 1.67 | 2.99 |

| O a | 27.26 | 30.26 | 45.05 | 20.05 |

| H/C, mole ratio | 1.25 | 0.23 | 0.65 | 0.30 |

| O/C, mole ratio | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.80 | 0.23 |

| Water | 1.51 | 1.43 | 1.87 | 2.11 |

| Oil | 7.93 | 7.48 | 9.82 | 9.48 |

| semi-coke | 85.33 | 80.70 | 79.23 | 78.01 |

| Gas | 5.23 | 10.39 | 9.08 | 10.40 |

| HHV b, MJ/kg | 3.07 | 8.45 | 7.23 | 12.34 |

| Constituent | FS | XS | JZ | WL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2O | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.00 |

| MgO | 1.11 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 0.00 |

| Al2O3 | 23.37 | 27.51 | 23.13 | 35.15 |

| SiO2 | 59.50 | 64.21 | 61.08 | 56.14 |

| P2O5 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| SO3 | 2.08 | 1.03 | 1.30 | 2.04 |

| K2O | 1.44 | 2.06 | 1.42 | 1.63 |

| CaO | 0.69 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 1.29 |

| TiO2 | 1.29 | 1.66 | 1.38 | 0.62 |

| MnO2 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 2.69 |

| Fe2O3 | 9.51 | 1.67 | 8.42 | 0.00 |

| Others | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.46 |

| Properties | Initiation Temperature (°C) | Peak Temperature (°C) | Peak Weight Loss Rate (wt% min−1) | Total Weight Loss (wt%) | Pyrolysis Interval (min) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (°C min−1) | 5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| FS | 386.9 | 336.3 | 324.5 | 460.6 | 474.5 | 481.3 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 9.0 | 14.1 | 14.6 | 13.8 | 6.7 | 4.8 |

| 85FS15WL | 370.5 | 321.3 | 280.4 | 458.2 | 473.9 | 497.2 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 8.6 | 15.0 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 7.5 | 5.1 |

| 70FS30WL | 369.7 | 268.0 | 208.9 | 458.8 | 470.5 | 460.2 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 8.4 | 15.6 | 16.3 | 17.1 | 8.1 | 5.6 |

| 55FS45WL | 315.1 | 258.8 | 210.2 | 458.2 | 471.5 | 480.3 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 7.6 | 16.7 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 8.7 | 6.6 |

| WL | 253.2 | 210.7 | 154.2 | 475.6 | 493.2 | 504.5 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 20.6 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 18.0 | 12.9 |

| XS | 374.2 | 359.4 | 324.5 | 440.5 | 451.1 | 460.0 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 9.2 | 16.5 | 15.9 | 15.3 | 6.6 | 4.9 |

| 85XS15WL | 368.1 | 333.4 | 260.8 | 440.0 | 451.1 | 459.6 | 2.0 | 4.1 | 8.8 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 16.4 | 6.7 | 5.1 |

| 70XS30WL | 343.1 | 273.3 | 210.3 | 440.5 | 451.4 | 459.6 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 8.4 | 17.7 | 17.7 | 17.1 | 7.5 | 5.7 |

| 55XS45WL | 273.1 | 238.6 | 189.2 | 441.1 | 455.1 | 461.2 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 6.5 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 18.6 | 12.8 | 8.6 |

| WL | 253.2 | 210.7 | 154.2 | 475.6 | 493.2 | 504.5 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 20.6 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 18.0 | 12.9 |

| JZ | 383.1 | 358.8 | 332.1 | 456.4 | 468.7 | 478.5 | 2.8 | 5.4 | 11.6 | 16.2 | 16.3 | 16.0 | 5.7 | 4.0 |

| 85JZ15WL | 375.7 | 331.3 | 275.9 | 455.3 | 466.3 | 477.5 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 10.2 | 17.2 | 17.1 | 15.7 | 5.3 | 4.4 |

| 70JZ30WL | 352.8 | 288.8 | 233.7 | 454.8 | 461.3 | 476.9 | 2.3 | 4.6 | 9.8 | 17.1 | 17.7 | 17.4 | 7.1 | 5.0 |

| 55JZ45WL | 315.1 | 258.8 | 212.3 | 454.3 | 473.8 | 477.5 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 9.1 | 17.8 | 18.2 | 17.7 | 7.3 | 5.5 |

| WL | 253.2 | 210.7 | 154.2 | 475.6 | 493.2 | 504.5 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 20.6 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 18.0 | 12.9 |

| Samples | Ea (kJ mol−1) | 5 °C min−1 | 10 °C min−1 | 15 °C min−1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f(α) | lnA | f(α) | lnA | f(α) | lnA | ||

| FS | 224.4 | (1 − α)2.1 | 35.9 | (1 − α)2 | 35.9 | (1 − α)1.9 | 35.9 |

| 85FS15WL | 216.7 | (1 − α)2.8 | 46.1 | (1 − α)2.8 | 46.1 | (1 − α)2.6 | 46.1 |

| 70FS30WL | 259.5 | (1 − α)2.1 | 35.2 | (1 − α)2.1 | 35.2 | (1 − α)2 | 35.2 |

| 55FS45WL | 210.7 | (1 − α)2.4 | 34.3 | (1 − α)2.3 | 34.3 | (1 − α)2.3 | 34.3 |

| WL | 239.8 | (1 − α)3 | 40.2 | (1 − α)3.6 | 39.8 | (1 − α)3.7 | 40.5 |

| XS | 274.7 | (1 − α)3.7 | 49.5 | (1 − α)3.4 | 49.0 | (1 − α)3.2 | 49.0 |

| 85XS15WL | 296.3 | (1 − α)4.1 | 55.0 | (1 − α)3.8 | 54.8 | (1 − α)3.6 | 54.6 |

| 70XS30WL | 302.7 | (1 − α)4 | 53.7 | (1 − α)3.8 | 53.7 | (1 − α)3.6 | 53.7 |

| 55XS45WL | 247.0 | (1 − α)3.4 | 40.5 | (1 − α)3.3 | 40.5 | (1 − α)3.2 | 40.5 |

| WL | 239.8 | (1 − α)3 | 40.2 | (1 − α)3.6 | 39.8 | (1 − α)3.7 | 40.5 |

| JZ | 216.3 | (1 − α)1.8 | 34.5 | (1 − α)1.7 | 34.5 | (1 − α)1.7 | 34.5 |

| 85JZ15WL | 251.7 | (1 − α)2 | 41.4 | (1 − α)2 | 41.4 | (1 − α)2 | 41.4 |

| 70JZ30WL | 237.9 | (1 − α)2.3 | 38.5 | (1 − α)2.2 | 38.5 | (1 − α)2.2 | 38.5 |

| 55JZ45WL | 201.6 | (1 − α)2 | 32.1 | (1 − α)2 | 32.1 | (1 − α)2 | 32.2 |

| WL | 239.8 | (1 − α)3 | 40.2 | (1 − α)3.6 | 39.8 | (1 − α)3.7 | 40.5 |

| Water | Oil | Semi-Coke | Gas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS | 1.5% | 7.9% | 85.3% | 5.2% |

| 85FS15WL | 1.5% | 7.9% | 84.1% | 6.5% |

| 70FS30WL | 1.6% | 8.0% | 82.8% | 7.6% |

| 55FS45WL | 1.6% | 8.2% | 82.3% | 7.9% |

| WL | 2.1% | 9.5% | 78.0% | 10.7% |

| XS | 1.4% | 7.5% | 80.7% | 10.4% |

| 85XS15WL | 1.4% | 7.4% | 85.2% | 6.0% |

| 70XS30WL | 1.4% | 7.3% | 84.6% | 6.8% |

| 55XS45WL | 1.7% | 8.3% | 83.6% | 6.5% |

| WL | 2.1% | 9.5% | 78.0% | 10.7% |

| JZ | 1.9% | 9.8% | 79.2% | 9.1% |

| 85JZ15WL | 1.8% | 9.4% | 78.4% | 10.4% |

| 70JZ30WL | 1.9% | 9.0% | 78.3% | 10.8% |

| 55JZ45WL | 1.9% | 8.8% | 77.9% | 11.4% |

| WL | 2.1% | 9.5% | 78.0% | 10.7% |

| Samples | Gasoline (C5–C12) | Kerosene (C13–C14) | Diesel (C15–C18) | Lubricating Oil (C19–C25) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS | 12.8 | 10.2 | 35.0 | 37.4 |

| 85FS15WL | 17.6 | 10.1 | 36.7 | 30.8 |

| 70FS30WL | 21.8 | 10.0 | 30.1 | 32.2 |

| 55FS45WL | 27.3 | 15.8 | 23.2 | 26.6 |

| WL | 64.1 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 23.5 |

| XS | 74.6 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 8.9 |

| 85XS15WL | 65.2 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 15.3 |

| 70XS30WL | 55.9 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 16.8 |

| 55XS45WL | 62.4 | 9.5 | 18.7 | 6.2 |

| WL | 64.1 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 23.5 |

| JZ | 42.0 | 6.7 | 13.2 | 33.1 |

| 85JZ15WL | 44.2 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 36.0 |

| 70JZ30WL | 46.8 | 7.4 | 13.5 | 32.3 |

| 55JZ45WL | 46.4 | 7.2 | 31.4 | 5.7 |

| WL | 64.1 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 23.5 |

| Mechanisms | Symbol | Differential Form f(α) | Integral Form G(α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Order of reaction | |||

| First-order | F1 | 1 − α | −ln(1 − α) |

| Second-order | F2 | (1 − α)2 | (1 − α)−1 − 1 |

| Third-order | F3 | (1 − α)3 | [(1 − α)−2 − 1]/2 |

| Diffusion | |||

| One-way transport | D1 | 0.5α | α2 |

| Two-way transport | D2 | [−ln(1 − α)]−1 | α+(1 − α)ln(1 − α) |

| Three-way transport | D3 | 1.5(1 − α)2/3[1 − (1 − α)1/3]−1 | [1 − (1 − α)1/3]2 |

| Ginstling–Brounshtein equation | D4 | 1.5[(1 − α)1/3 − 1]−1 | (1 − 2α/3) − (1 − α)2/3 |

| Limiting surface reaction between both phases | |||

| One dimension | R1 | 1 | α |

| Two dimensions | R2 | 2(1 − α)1/2 | 1−(1 − α)1/2 |

| Three dimensions | R3 | 3(1 − α)2/3 | 1−(1 − α)1/3 |

| Random nucleation and nuclei growth | |||

| Two-dimensional | A2 | 2(1 − α)[−ln(1 − α)]1/2 | [−ln(1 − α)]1/2 |

| Three-dimensional | A3 | 3(1 − α)[−ln(1 − α)]2/3 | [−ln(1 − α)]1/3 |

| Exponential nucleation | |||

| Power law, n = 1/2 | P2 | 2α1/2 | α1/2 |

| Power law, n = 1/3 | P3 | 3α2/3 | α1/3 |

| Power law, n = 1/4 | P4 | 4α3/4 | α1/4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meng, Y.; Xu, F.; Feng, J.; Xiao, H.; Pang, C. Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Chinese Oil Shales for Enhanced Shale Oil Yield and Quality: A Kinetic and Experimental Study. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111076

Meng Y, Xu F, Feng J, Xiao H, Pang C. Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Chinese Oil Shales for Enhanced Shale Oil Yield and Quality: A Kinetic and Experimental Study. Catalysts. 2025; 15(11):1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111076

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeng, Yang, Feng Xu, Jiayong Feng, Hang Xiao, and Chengheng Pang. 2025. "Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Chinese Oil Shales for Enhanced Shale Oil Yield and Quality: A Kinetic and Experimental Study" Catalysts 15, no. 11: 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111076

APA StyleMeng, Y., Xu, F., Feng, J., Xiao, H., & Pang, C. (2025). Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis of Chinese Oil Shales for Enhanced Shale Oil Yield and Quality: A Kinetic and Experimental Study. Catalysts, 15(11), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111076