Modified Metal-Doped Fe-Al Catalysts for H2-Rich Syngas Production from Microwave-Assisted Gasification of HDPE Plastic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effect of Metal Doping

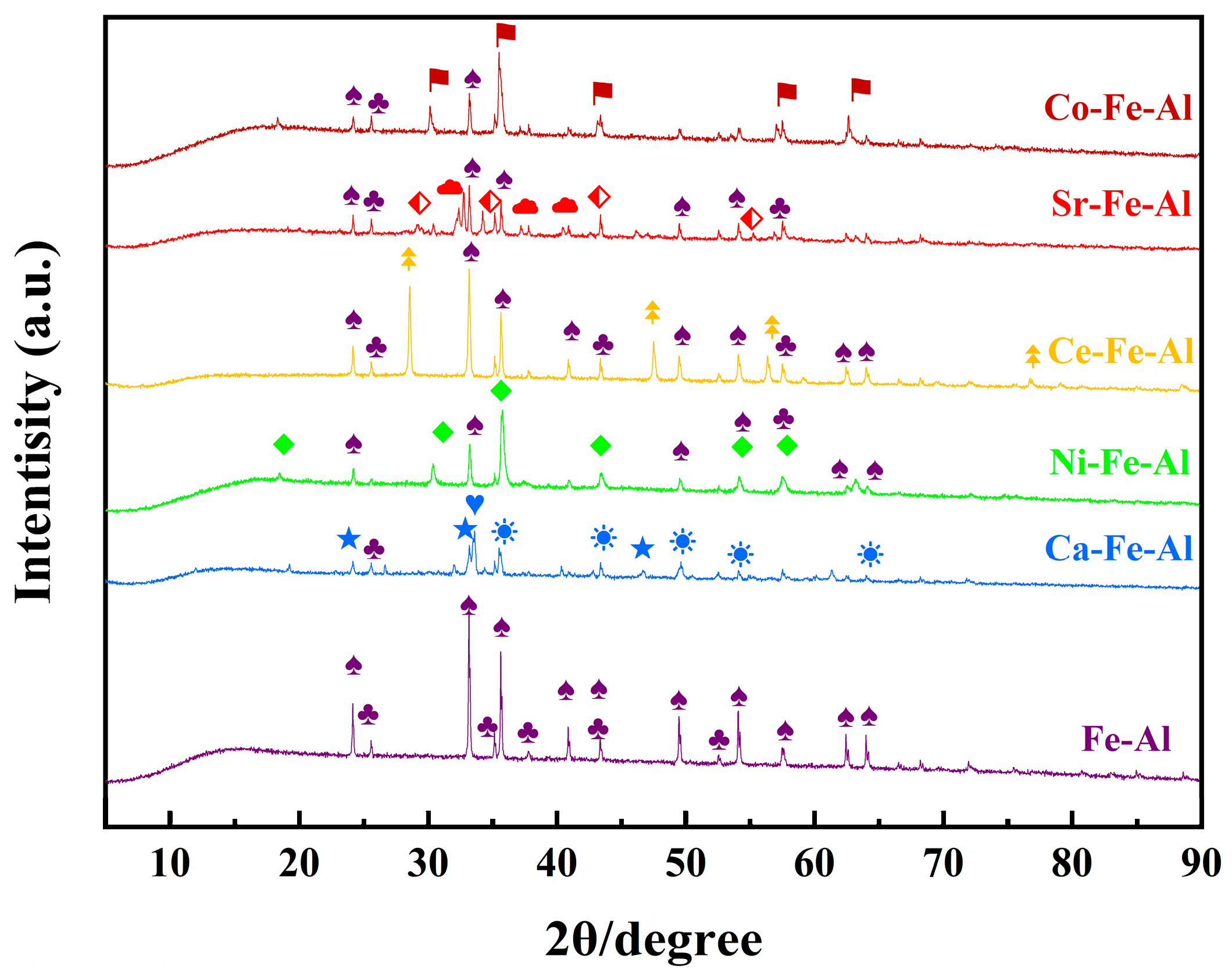

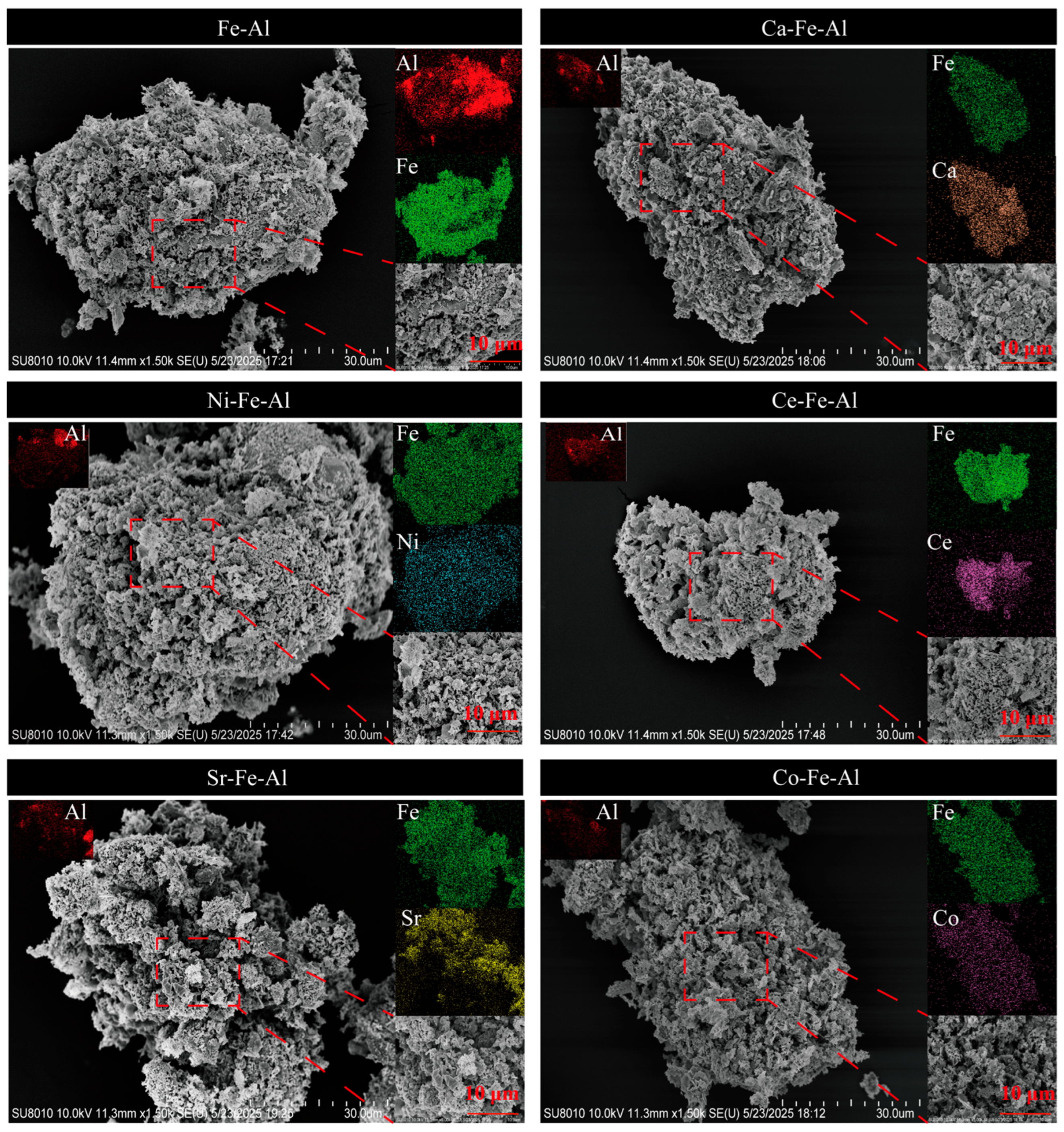

2.1.1. Characterization of Fresh Redox Catalysts

2.1.2. Product Distribution

2.1.3. Gas Composition

2.2. Effect of Microwave Power

2.2.1. Microwave Heating Performance and Energy Consumption

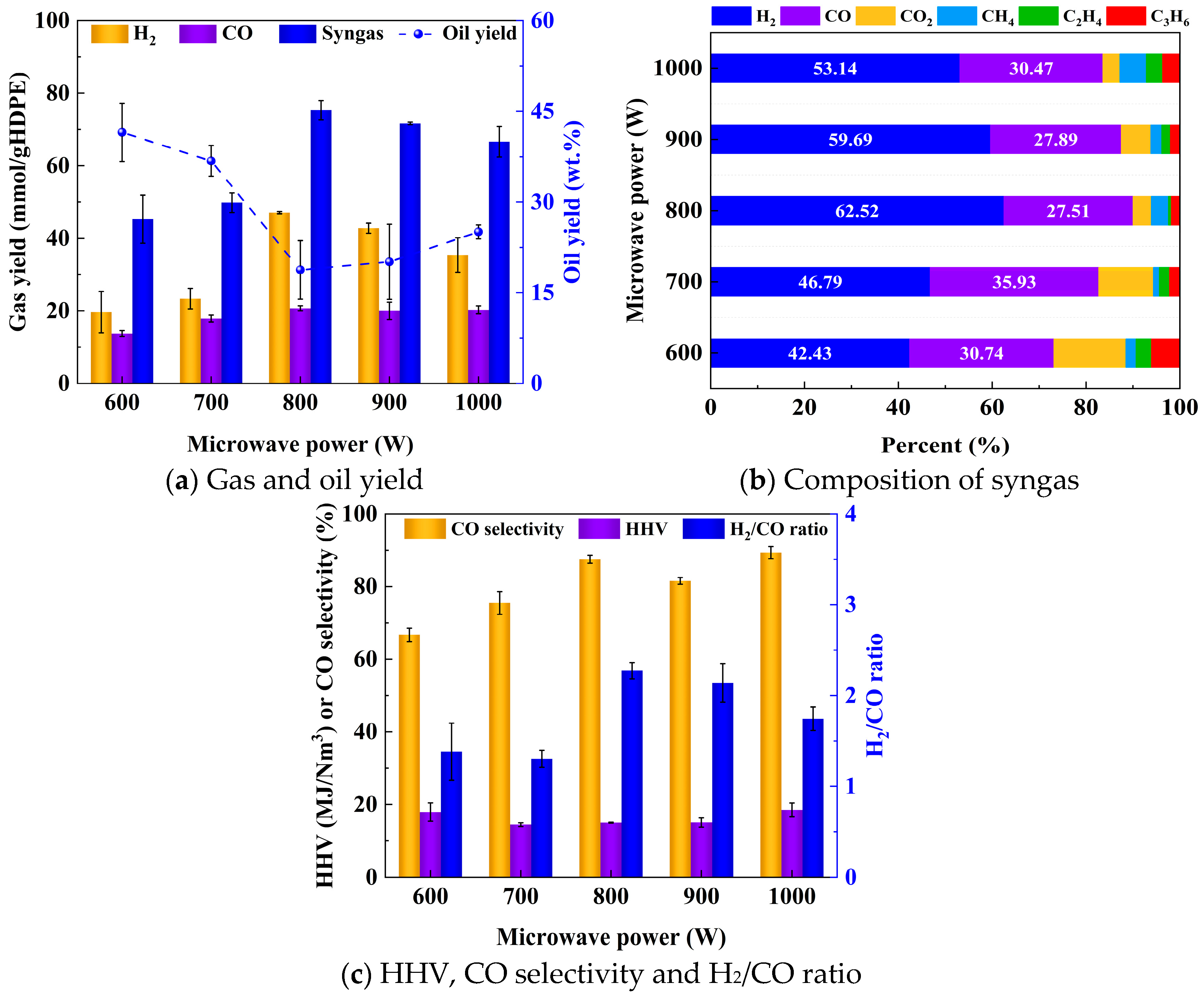

2.2.2. Product Distribution

2.2.3. Gas Composition

2.3. Effect of Different Redox Catalysts on Plastic Mass Ratio

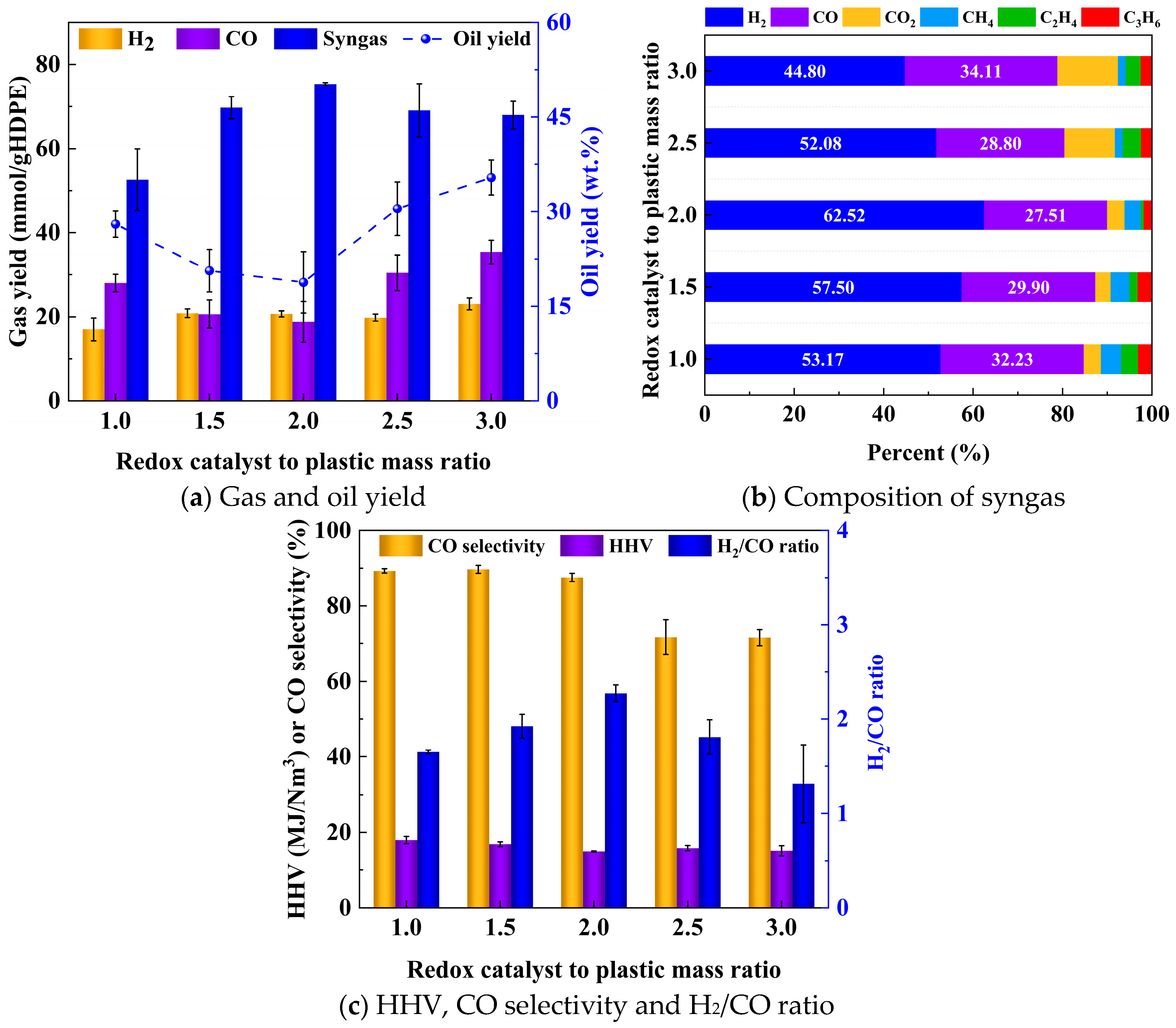

2.3.1. Product Distribution

2.3.2. Gas Composition

2.3.3. XRD and SEM Analysis of Reduced and Regenerated Ni-Fe-Al

2.4. Mechanism for the CLG Process

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis Method of Redox Catalysts

3.3. Experimental Procedures

3.4. Analysis and Characterization Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDPE | high-density polyethylene |

| CLG | chemical loop gasification |

| TGA | thermogravimetric analysis |

| DFT | density functional theory |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| TGA-MS | thermogravimetric analysis combined with mass spectrometry |

| CLP | chemical looping process |

| MAP | microwave-assisted pyrolysis |

| SiC | silicon carbide |

| Vl | volatiles |

| FC | fixed carbon |

| TR | the time required for reaching target temperature in vacuum stage |

| Hr | heating rate |

| Mp | microwave power |

| V | vacuum stage |

| A | air stage |

| Ec (V + A) | the energy input of the entire experiment, which was calculated by dividing the energy consumption by the molar yield of synthesis gas. |

| HHV | the higher heating value of syngas |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| EDS | dispersive spectrometer |

| TG | thermogravimetric analysis |

| φH2/CO | H2/CO ratio |

| VCO | the volumetric concentration of CO in syngas |

| VCO2 | the volumetric concentration of CO2 |

| VH2 | the volumetric concentration of H2 in syngas |

| ηC | carbon conversion efficiency |

| ηH | hydrogen conversation efficiency |

| Hi | the mass of hydrogen in the component i |

| Hj | the mass of hydrogen in the component j |

| Cfeedstock | the mass of carbon in the feed HDPE |

| Hfeedstock | the mass of hydrogen in the feed HDPE |

| MGYv | the molar yield of syngas generated during the vacuum stage |

| vi | the volume fraction of gas constituent i during vacuum phase |

| Mi | relative mass of gas constituent i |

| MGYi | the molar yield of gas constituent i in the vacuum phase |

| OY | oil yield |

| GY | gas yield |

| m1 | the mass increasement of thermocouple, determined by weighing before and after vacuum stage, g |

| m2 | the mass increasement of condenser units, determined by weighing before and after vacuum stage, g |

| m3 | the mass reduction of reactor, SiC, HDPE and redox catalyst, determined by weighing before and after vacuum stage, g |

| Al2O3 | aluminum oxide |

| Ni-Fe-Al-V | spent Ni-Fe-Al from vacuum stage |

| Ni-Fe-Al-VA | Ni-Fe-Al obtained after air introduction stage |

References

- Bahlouli, H.A.; Alghamdi, R.; Manos, G. Coke Characterization and Re-Activation Energy Dynamics of Spent FCC Catalyst in the Catalytic Pyrolysis of Polyolefins. Catalysts 2025, 15, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Bai, B.; Zhang, R.; Ma, J.; Mao, L.; Shi, J.; Jin, H. Study on gasification characteristics and kinetics of polyformaldehyde plastics in supercritical water. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busto, M.; Dosso, L.A.; Nardi, F.; Badano, J.M.; Vera, C.R. Catalytic and Non-Catalytic Co-Gasification of Biomass and Plastic Wastes for Energy Production. Catalysts 2025, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; Guo, S.; Shi, Z.; Han, T.; Gond, R.; Jönsson, P.G.; Yang, W. Carbon and H2 recoveries from plastic waste by using a metal-free porous biocarbon catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 404, 136926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Gu, M.; Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Yao, H. Enhanced gasification of waste plastics for hydrogen production: Experiment and simulation. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 120, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracciale, M.P.; Damizia, M.; De Filippis, P.; de Caprariis, B. Clean Syngas and Hydrogen Co-Production by Gasification and Chemical Looping Hydrogen Process Using MgO-Doped Fe2O3 as Redox Material. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, D.; Shao, D.; An, F.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. Targeted migration mechanisms of nitrogen-containing pollutants during chemical looping co-gasification of coal and microalgae. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Panitz, F.; Moghaddam, E.M.; Ströhle, J.; Epple, B.; He, C.; Konttinen, J. Performance evaluation of biomass chemical looping gasification in a fluidized bed reactor using industrial waste as oxygen carrier. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 427, 132447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Fu, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y. Microwave-assisted chemical looping gasification of lignite coal for CO-rich syngas production. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 120, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, M.; Wang, J.; Jin, H.; Wei, W. Thermochemical conversion and gasification of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) in supercritical CO2: A sustainable approach to plastic waste management. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiara, T.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Condori, Ó.; García-Quiles, L.; Abad, A. Identification of oxygen carriers for chemical recycling of plastic waste using chemical looping technologies. Fuel 2025, 394, 135284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Gao, Z.; Guo, Z.; Liu, P.; Yao, D. Sustainable hydrogen production from waste plastics via staged chemical looping gasification with iron-based oxygen carrier. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2025, 23, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; You, C.; Wang, H. Chemical looping gasification of waste plastics for syngas production using NiO/Al2O3 as dual functional material. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawa, T.; Martinez, M.P.S.; Sajjadi, B. Enhanced Production of Hydrogen through Modified Brownmillerite Ca2Fe2-xMxO5 (M: Co, Cu, Ni) for Chemical Looping Gasification. Fuel 2025, 390, 134490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fang, S.; Lin, Y.; Song, D.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, H.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, H. Chemical looping gasification of benzene as a biomass tar model compound using hematite modified by Ni as an oxygen carrier. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 15, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Ismailov, A.; Moghaddam, E.M.; He, C.; Konttinen, J. Evaluation of low-cost oxygen carriers for biomass chemical looping gasification. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhao, W.; Xiong, Q.; Li, B. Microwave-assisted chemical looping gasification of sugarcane bagasse biomass using Fe3O4 as oxygen carrier for H2/CO-rich syngas production. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadri, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, D. Experimental Study on Chemical Looping Co-gasification of Alfalfa and Polyethylene with Iron Ore as the Oxygen Carrier for High H2/CO Production. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 6939–6948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, R. Insights into the relationship between microstructural evolution and deactivation of Al2O3 supported Fe2O3 oxygen carrier in chemical looping combustion. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 188, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Study on the synergistic effect and oxygen vacancy of CeO2/Fe2O3 oxygen carrier for improving reactivity in carbon monoxide chemical looping combustion. Fuel 2024, 357, 129832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Chen, Y.; Mai, H.; Zeng, Q.; Lv, J.; Jiang, E.; Hu, Z. Uniformly dispersed NiFeAlO4 as oxygen carrier for chemical looping steam methane reforming to produce syngas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H. Enhanced cyclic redox reactivity of hematite via Sr doping in chemical looping combustion. J. Energy Inst. 2022, 100, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, K.; Li, B.; Wu, J. The search of proper oxygen carriers for chemical looping partial oxidation of carbon. Appl. Energy 2017, 190, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozen, H.; Guo-qiang, W.; Hai-bin, L.; Fang, H.; Zhen, H. Chemical-looping gasification of biomass in a 10 kWth interconnected fluidized bed reactor using Fe2O3/Al2O3 oxygen carrier. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2014, 42, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ok, Y.S.; Wang, C. Sustainable and highly efficient recycling of plastic waste into syngas via a chemical looping scheme. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 8953–8963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Wang, T.; Weng, T.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, S.; Ma, W. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass and electrode materials from spent lithium-ion batteries: Characteristics and product compositions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222 Pt 4, 119899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xie, Q.; Nie, Y. Improvement of essential oil yield in the pyrolysis oil of Cinnamomum camphora leaves using a microwave-assisted segment heating method: Product analysis, mechanism and kinetic model. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 189, 107065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potnuri, R.; Rao, C.S.; Surya, D.V.; Kumar, A. Hospital plastic waste valorization through microwave-assisted Pyrolysis: Experimental and modeling studies via machine learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 514, 145772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvej; Sharma, A.K. Effect of insulation materials and power on microwave heating characteristics of SiC susceptor under material–specific parametric conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 204, 109229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhao, W.; Li, B. Microwave-assisted chemical looping gasification of plastics for H2-rich gas production. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Yu, X.Y.; Su, X.; Gao, X.; Huang, Z.Q.; Yang, B.; Chang, C.R. Dopant-Enhanced harmonization of α-Fe2O3 oxygen migration and surface catalytic reactions during chemical looping reforming of methane. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, D.; Tang, Q.; Abuelgasim, S.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Luo, J.; Zhao, Z.; Abdalazeez, A.; Zhang, R. Chemical looping gasification of biomass char for hydrogen-rich syngas production via Mn-doped Fe2O3 oxygen carrier. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 12636–12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, R.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, P.; Meng, X.; Li, P. Performance improvement and the mechanisms of red mud oxygen carrier in chemical looping gasification using strontium doping strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.A.; Mohammed, A.A.A.; Binous, H.; Razzak, S.A.; Hossain, M.M. Ni-Fe bimetallic oxides on La modified Al2O3 as an oxygen carrier for liquid fuel based chemical looping combustion. Fuel 2020, 263, 116670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, M.H.; Lotfi-Varnoosfaderani, M.; Moghadasin, M.H. Catalytic conversion of bio-renewable glycerol to pure hydrogen and syngas: Energy management and mitigation of environmental pollution. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 247, 114719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, S.; Hu, J.; Chen, A.; Rony, A.H.; Russell, C.K.; Xiang, W.; Fan, M.; Dyar, M.D.; Dklute, E.C. Ca2Fe2O5: A promising oxygen carrier for CO/CH4 conversion and almost-pure H2 production with inherent CO2 capture over a two-step chemical looping hydrogen generation process. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Fan, C.; Tang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Zang, Z.; Li, L.; Yu, X.; Lu, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. The effects of Co doping for Fe metal on boosting hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions. Fuel 2025, 381, 133558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Yang, M.; Huang, Z.; Bai, H.; Chang, G.; He, F.; Yi, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, A.; Zhao, K.; et al. Syngas production from lignite via chemical looping gasification with hematite oxygen carrier enhanced by exogenous metals. Fuel 2022, 321, 124119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liao, Y.; Liang, S.; Zhang, T.; Ma, X. Enhanced syngas production via plastic rubber chemical looping gasification: Role of iron–nickel oxide oxygen carriers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 95, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xing, Y.; Hong, C. Ca sorption/enhanced Fe-based oxygen carriers for chemical looping gasification of microalgae. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, K.; Wei, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, H. Chemical-looping water splitting over ceria-modified iron oxide: Performance evolution and element migration during redox cycling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 179, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F.; Turner, J.V.; Wilson, R.; Chen, L.; de Looze, G.; Kingman, S.W.; Dodds, C.; Dimitrakis, G. State-of-the-art in microwave processing of metals, metal powders and alloys. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Gong, G.; Ma, R.; Sun, S.; Cui, C.; Cui, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, N. Study on high-value products of waste plastics from microwave catalytic pyrolysis: Construction and performance evaluation of advanced microwave absorption-catalytic bifunctional catalysts. Fuel 2023, 346, 128296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, X. Co, Ni and Cu-doped Ca2Fe2O5-based oxygen carriers for enhanced chemical looping hydrogen production. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 114, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detchusananard, T.; Im-orb, K.; Maréchal, F.; Arpornwichanop, A. Analysis of the sorption-enhanced chemical looping biomass gasification process: Performance assessment and optimization through design of experiment approach. Energy 2020, 207, 118190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ren, Z.; Hu, Q.; Yao, D.; Yang, H. Upcycling plastic waste into syngas by staged chemical looping gasification with modified Fe-based oxygen carriers. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Tao, X.; et al. A review on waste tires pyrolysis for energy and material recovery from the optimization perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, P.; Ku, Y.; Wu, H.; Kuo, Y.; Tseng, Y. Chemical looping combustion of polyurethane and polypropylene in an annular dual-tube moving bed reactor with iron-based oxygen carrier. Fuel 2014, 135, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Ruj, B.; Sadhukhan, A.K.; Gupta, P. Impact of fast and slow pyrolysis on the degradation of mixed plastic waste: Product yield analysis and their characterization. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Tian, W. Multi-level optimization of biomass chemical looping gasification process based on composite oxygen carrier. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 287, 119727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Ruj, B. Time and temperature depended fuel gas generation from pyrolysis of real world municipal plastic waste. Fuel 2016, 174, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalazeez, A.; Wang, W.; Abuelgasim, S.; Liu, C.; Xu, T.; Liu, D. Chemical looping co-gasification of cotton stalk and rice husk-derived biochar for syngas production with BaFe2O4/MgAl2O4 oxygen carrier. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 190, 107397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samprón, I.; de Diego, L.F.; García-Labiano, F.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Abad, A.; Adánez, J. Biomass Chemical Looping Gasification of pine wood using a synthetic Fe2O3/Al2O3 oxygen carrier in a continuous unit. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 316, 123908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Veksha, A.; Foo Jin Jun, T.F.; Lisak, G. Upgrading waste plastic derived pyrolysis gas via chemical looping cracking–gasification using Ni–Fe–Al redox catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 438, 135580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, X.; Li, W.; Slocombe, D.; Gao, Y.; Banerjee, I.; Gonzalez-Cortes, S.; Yao, B.; AlMegren, H.; Alshihri, S.; Dilworth, J.; et al. Microwave-initiated catalytic deconstruction of plastic waste into hydrogen and high-value carbons. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Redox Catalysts | TR (min) | Hr (°C/min) |

|---|---|---|

| Fe-Al | 5.00 | 155.2 |

| Ca-Fe-Al | 4.25 | 182.6 |

| Ce-Fe-Al | 3.41 | 227.5 |

| Sr-Fe-Al | 3.21 | 241.7 |

| Co-Fe-Al | 2.35 | 330.2 |

| Ni-Fe-Al | 3.33 | 233.0 |

| Mp (W) | TR (min) | Hr (°C/min) | Ec (V+A) (kWh/Molgas) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 600 | 7.5 | 103.5 | 9.20 |

| 700 | 4.0 | 194.0 | 6.52 |

| 800 | 3.33 | 233.0 | 3.52 |

| 900 | 1.5 | 517.3 | 3.18 |

| 1000 | 1.0 | 776.0 | 3.24 |

| Redox Catalyst to Plastic Mass Ratio | TR (min) | Hr (°C/min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 4.31 | 180.0 |

| 1.5 | 4.00 | 194.0 |

| 2.0 | 3.33 | 233.0 |

| 2.5 | 3.00 | 258.7 |

| 3.0 | 2.55 | 304.3 |

| Ultimate Analysis (wt.%) | Proximate Analysis (wt.%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | S | N | Vl | FC | Ash |

| 85.88 | 13.34 | 0 | 0.015 | 99.40 | 0.32 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Zhao, W.; Ahmad, F.; Zhang, Y. Modified Metal-Doped Fe-Al Catalysts for H2-Rich Syngas Production from Microwave-Assisted Gasification of HDPE Plastic. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111032

Zhou J, Liu C, Zhao W, Ahmad F, Zhang Y. Modified Metal-Doped Fe-Al Catalysts for H2-Rich Syngas Production from Microwave-Assisted Gasification of HDPE Plastic. Catalysts. 2025; 15(11):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111032

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jingmo, Chaoyue Liu, Wenke Zhao, Faizan Ahmad, and Yaning Zhang. 2025. "Modified Metal-Doped Fe-Al Catalysts for H2-Rich Syngas Production from Microwave-Assisted Gasification of HDPE Plastic" Catalysts 15, no. 11: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111032

APA StyleZhou, J., Liu, C., Zhao, W., Ahmad, F., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Modified Metal-Doped Fe-Al Catalysts for H2-Rich Syngas Production from Microwave-Assisted Gasification of HDPE Plastic. Catalysts, 15(11), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111032