Co-Production of Methanol and Methyl Formate via Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 over Promoted Cu/ZnO Catalyst Supported on Al2O3 and SBA-15

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

3.1.1. Preparation of Catalyst Supports (Al2O3 and SBA-15)

3.1.2. Preparation of Cu/ZnO-Based Catalyst with the Addition of Promoters

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

3.3. Catalyst Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Gong, J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3703–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.A. Beyond oil and gas: The methanol economy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005, 44, 2636–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciani, J.; Mudiyanselage, K.; Xu, F.; Baber, A.E.; Evans, J.; Senanayake, S.D.; Stacchiola, D.J.; Liu, P.; Hrbek, J.; Fernández Sanz, J.; et al. Highly active copper-ceria and copper-ceria-titania catalysts for methanol synthesis from CO2. Science 2014, 345, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortelli, E.E.; Wambach, J.; Wokaun, A. Methanol synthesis reactions over a CuZr based catalyst investigated using periodic variations of reactant concentrations. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 216, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchen, G.C.; Denny, P.J.; Jennings, J.R.; Spencer, M.S.; Waugh, K.C. Synthesis of methanol: Part 1. Catalysts and kinetics. Appl. Catal. 1988, 36, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, S.I.; Usui, M.; Ito, H.; Takezawa, N. Mechanisms of methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide and from carbon monoxide at atmospheric pressure over Cu/ZnO. J. Catal. 1995, 157, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.S. The role of zinc oxide in Cu/ZnO catalysts for methanol synthesis and the water-gas shift reaction. Top. Catal. 1999, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.; Studt, F.; Kasatkin, I.; Kühl, S.; Hävecker, M.; Abild-Pederson, F.; Zander, S.; Girgsdies, S.; Kurr, P.; Kniep, B.L.; et al. The active site of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 industrial catalysts. Science 2012, 336, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.A.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Mohamed, A.R. Recent development in catalytic technologies for methanol synthesis from renewable sources: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 44, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitani, T.; Nakamura, J. The chemical modification seen in the Cu/ZnO methanol synthesis catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 191, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Lu, G.Q.; Yan, Z.F.; Beltramini, J. Recent advances in catalysts for methanol synthesis via hydrogenation of CO and CO2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 6518–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, H.B.; Lin, G.D.; Yuan, Y.Z.; Tsai, K.R. Highly active CNT-Promoted Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 catalyst for methanol synthesis from H2/CO/CO2. Catal. Lett. 2003, 85, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, O.B.; Tasfy, S.F.H.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Uemura, Y. Co-synthesis of methanol and methyl formate from CO2 hydrogenation over oxalate ligand functionalized ZSM-5 supported Cu/ZnO catalyst. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 17, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasfy, S.F.H.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Shaharun, M.S.; Subbarao, D. The role of support morphology on the performance of Cu/ZnO-catalyst for hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. In AIP Conference Proceedings, Proceedings of the 23rd Scientific Conference of Microscopy Society Malaysia, Tronoh, Malaysia, 10–12 December 2014; Hussain, P., Bhat, A.H., Chowdury, S., Mohamed, N.M., Othman, F., Mamat, O., Eds.; AIP Publishing: Woodbury, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabidi, N.A.M.; Tasfy, S.F.H.; Shaharun, M.S. Effects of Nb promoter on the properties of Cu/ZnO/SBA-15 catalyst and performance in methanol production. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 708, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasfy, S.F.H.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Shaharun, M.S.; Subbarao, D. Effect of Mn and Pb promoters on the performance of Cu/ZnO-Catalyst in CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 625, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Li, F.; Gao, P.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Wei, W.; Zhong, L.; Sun, Y. Methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation over La–M–Cu–Zn–O (M = Y, Ce, Mg, Zr) catalysts derived from perovskite-type precursors. J. Power Source. 2014, 251, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, S.; Watanabe, F.; Kiyota, K.; Shimoda, N.; Hayashi, R.; Takahashi, M.; Nariyuki, A.; Igarashi, A.; Satokawa, S. Ag addition to CuO-ZrO2 catalysts promotes methanol synthesis via CO2 hydrogenation. J. Catal. 2017, 351, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słoczyński, J.; Grabowski, R.; Olszewski, P.; Lachowska, M.; Skrzypek, J.; Stoch, J. Effect of Mg and Mn oxide additions on structural and adsorptive properties of Cu/ZnO/ZrO2 catalysts for the methanol synthesis from CO2. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 249, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, L.; Ishihara, T. Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol over Cu/AlCeO catalyst. Catal. Today 2019, 339, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wen, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Fu, M.; Wu, J.; Ye, D.; et al. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over Cu/ZnO plate model catalyst: Effects of reducing gas induced Cu nanoparticle morphology. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitani, T. Enhancement of the catalytic performance and active site clarification of Cu/ZnO based catalysts for methanol synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 2020, 63, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Shaharun, M.S.; Naeem, A.; Tasleem, S.; Johan, M.R. Carbon nanofiber-based copper/zirconia catalyst for hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. J. CO2. Util. 2017, 21, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Cheng, W.H.; Lin, S.S. Study of reverse water gas shift reaction by TPD, TPR and CO2 hydrogenation over potassium-promoted Cu/SiO2 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 238, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, D.; Beckmann, L.; Walter, J.; Bertau, M. Conversion of green methanol to methyl formate. Catalysts 2021, 11, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The determination of pore volume and area distributions in porous substances. I. Computations from nitrogen isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasfy, S.F.H.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Shaharun, M.S. Methanol production via CO2 hydrogenation reaction: Effect of catalyst support. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2017, 14, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasfy, S.F.H. Development and Performance Analysis of Cu-ZnO/SBA-15 Catalysts for Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Petronas, Seri Iskandar, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, N.S.A. Synthesis, Characterization and Performance of Copper-Zinc Oxide with Mixed Promoter Catalyst for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Master’s Thesis, Universiti Teknologi Petronas, Seri Iskandar, Malaysia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Chen, S.; Fei, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol: Study of synergistic effect on adsorption properties of CO2 and H2 in CuO/ZnO/ZrO2 system. Catalysts 2015, 5, 1846–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, S.; Fan, H. Enhancement of stability and activity of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts by microwave irradiation for liquid phase methanol synthesis. Fuel 2013, 106, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Ye, X. Structure and photoluminescent properties of ZnO encapsulated in mesoporous silica SBA-15 fabricated by two-solvent strategy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2009, 4, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, B.; Quan, G.; Li, F.; Wu, Q.; Dian, L.; Dong, Y.; Li, G.; Wu, C. Increasing the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble carbamazepine using immediate-release pellets supported on SBA-15 mesoporous silica. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 5807–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, J.; Melosh, N.; Fredrickson, G.H.; Chmelka, B.F.; Stucky, G.D. Triblock copolymer syntheses of mesoporous silica with periodic 50 to 300 angstrom pores. Science 1998, 279, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.N.K.; Yen, N.T.; Hau, N.D.; Tran, H.L. Synthesis and characterization of mesoporous silica SBA-15 and ZnO/SBA-15 photocatalytic materials from the ash of brickyards. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 8456194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.V.; Parishan, S.; Sagaltchik, A.; Ahi, H.; Trunschke, A.; Schomäcker, R.; Thomas, A. Stepwise methane-to-methanol conversion on CuO/SBA-15. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12592–12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D. A highly efficient Cu-ZnO/SBA-15 catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to CO under atmospheric pressure. Catal. Today 2022, 402, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sarofim, A.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Complete oxidation of carbon monoxide and methane over metal-promoted fluorite oxide catalysts. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1994, 49, 4871–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.; Shaharun, M.S.; Subbaro, D.; Naeem, A.; Hussain, F. Influence of niobium on carbon nanofibres based Cu/ZrO2 catalysts for liquid phase hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Catal. Today 2016, 259, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.R.; Sharratt, A.P.; Jackson, S.D.; Griffiths, R.W.; Gladden, L.F.; Robertson, F.J.; Webb, G. Temperature-programmed reduction of nickel/silica catalysts using [3H]-hydrogen. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1992, 166, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, O.P.; Klementiev, K.V.; van den Berg, M.W.E.; Koc, N.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Birkner, A.; Wöll, C.; Gies, H.; Grünert, W. Reduction of copper in porous matrixes. Stepwise and autocatalytic reduction routes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 20979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprun, W.; Lutecki, M.; Haber, T.; Papp, H. Acidic catalysts for the dehydration of glycerol: Activity and deactivation. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2009, 309, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

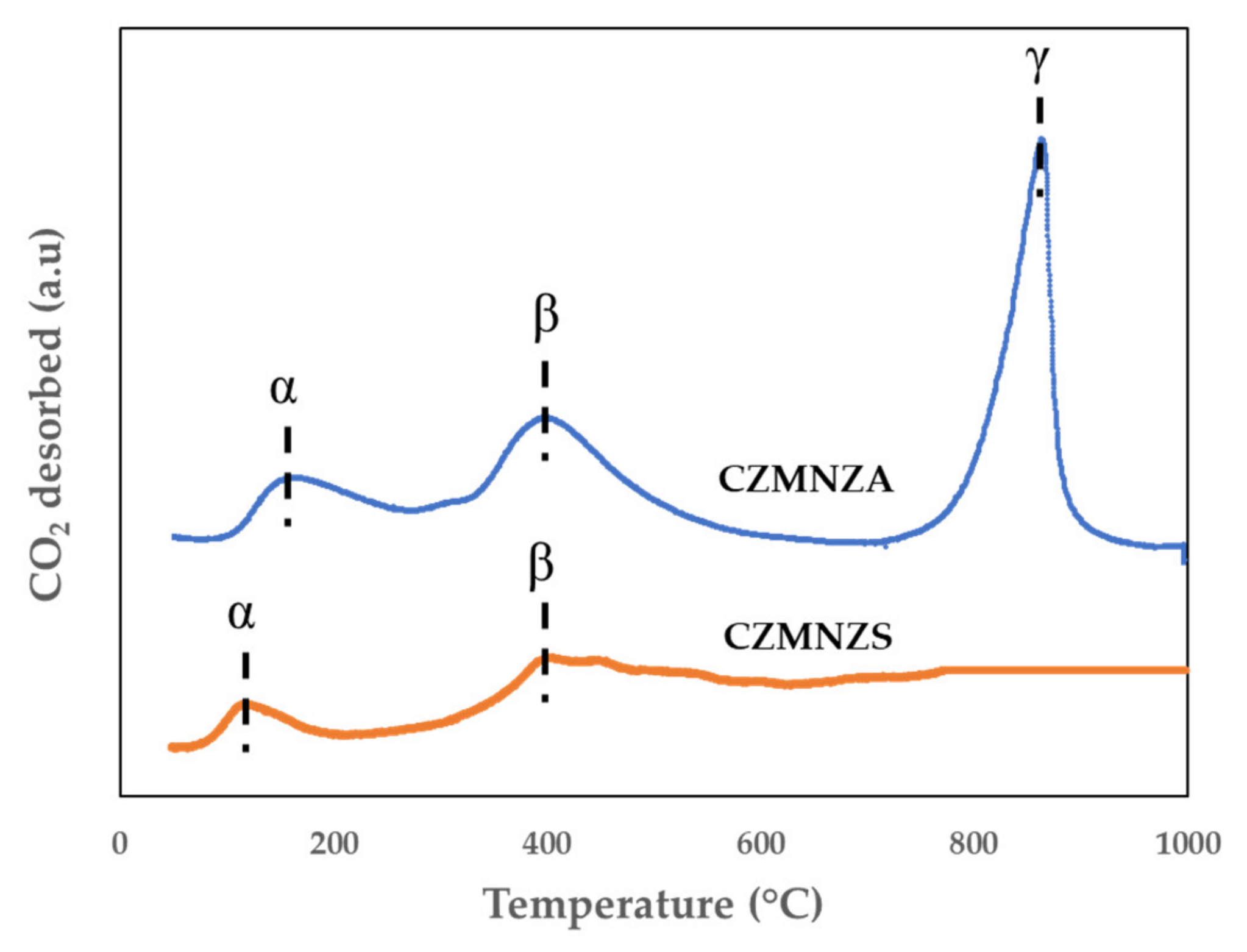

- Tursunov, O.; Kustov, L.; Tilyabaev, Z. Methanol synthesis from the catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 over CuO–ZnO supported on aluminum and silicon oxides. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 78, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata, D.B.C.; Likozar, B. The role of copper oxidation state in Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts in CO2 hydrogenation and methanol productivity. Renew. Energy 2019, 140, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.K.; Wong, Y.J.; Chai, S.P.; Mohamed, A.R. Carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol over multi-functional catalyst: Effects of reactants adsorption and metal-oxide(s) interfacial area. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 62, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Li, F.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Wei, W.; Zhong, L. Influence of modifier (Mn, La, Ce, Zr and Y) on the performance of Cu/Zn/Al catalysts via hydrotalcite-like precursors for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 468, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, K.; Ma, H.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Cr, Zr-incorporated hydrotalcites and their application in the synthesis of isophorone. Catal. Commun. 2010, 11, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannilla, C.; Bonura, G.; Rombi, E.; Arena, F.; Frusteri, F. Highly effective MnCeOx catalysts for biodiesel production by transesterification of vegetable oils with methanol. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 382, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.W.E.; Polarz, S.; Tkachenko, O.P.; Klementiev, K.V.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Khodeir, L.; Gies, H.; Muhler, M.; Grünert, W. Cu/ZnO aggregates in siliceous mesoporous matrices: Development of a new model methanol synthesis catalyst. J. Catal. 2006, 241, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kattel, S.; Ramírez, P.J.; Chen, J.G.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Liu, P. Response to comment on active sites for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on Cu/ZnO catalysts. Science 2017, 357, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoon, T.; Chalorngtham, J.; Dumrongbunditkul, P.; Chareonpanich, M.; Limtrakul, J. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over Cu/ZrO2 catalysts: Effects of zirconia phases. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 293, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, S.-I.; Moribe, S.; Kanamori, Y.; Kakudate, M.; Takezawa, N. Preparation of a coprecipitated Cu/ZnO catalyst for the methanol synthesis from CO2—effects of the calcination and reduction conditions on the catalytic performance. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 207, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobl, K.; Angelo, L.; Zimmermann, Y.; Sall, S.; Parkhomenko, K.; Roger, A.C. In situ infrared study of formate reactivity on water-gas shift and methanol synthesis catalysts. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2015, 18, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Choi, S.; Thompson, L.T. Ethyl formate hydrogenolysis over Mo2C-based catalysts: Towards low temperature CO and CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Catal. Today 2016, 259, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indu, B.; Ernst, W.R.; Gelbaum, L.T. Methanol-formic acid esterification equilibrium in sulfuric acid solutions: Influence of sodium salts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1993, 32, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

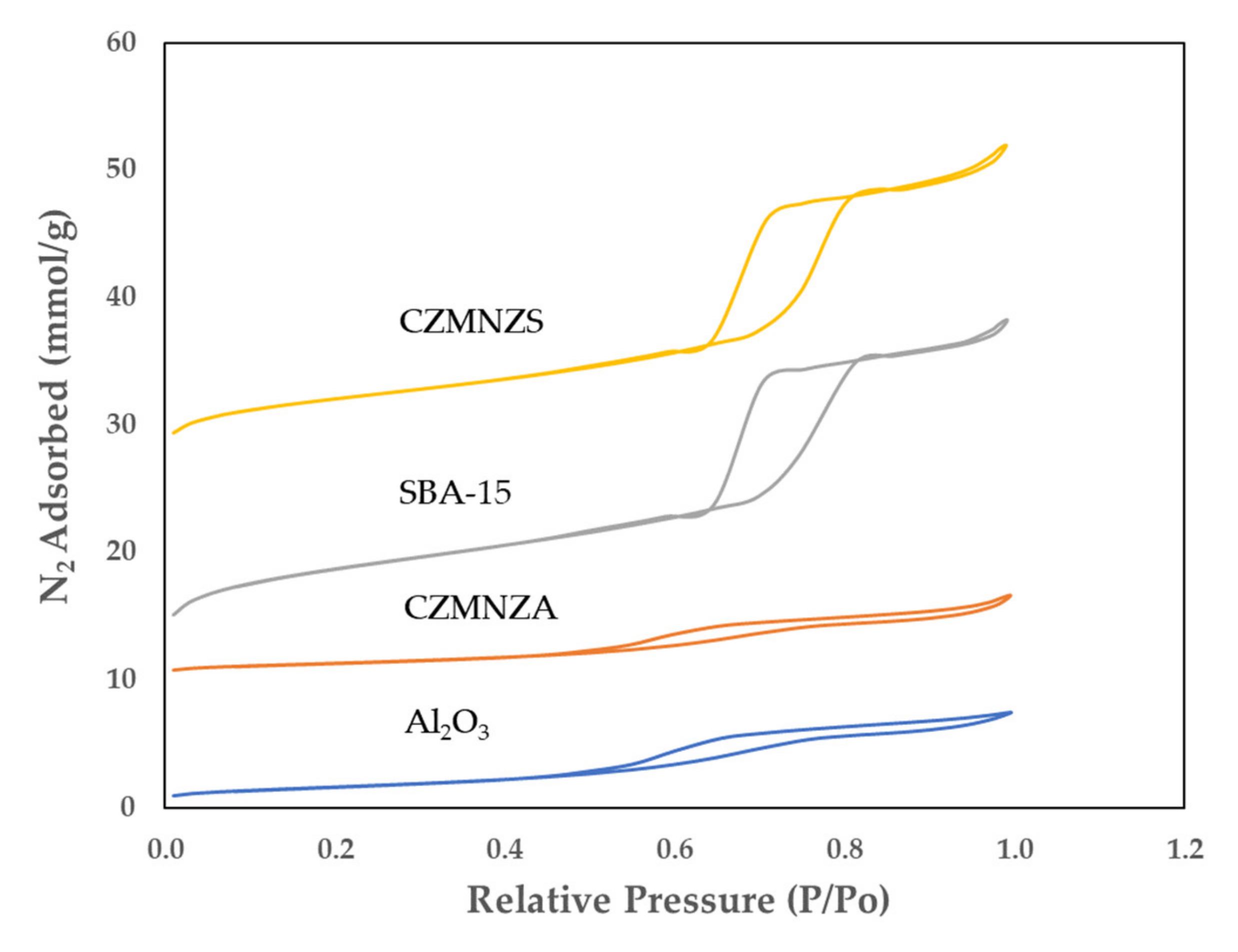

| Sample | SBET (m2/g) | VP (cm3/g) | DBJH (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | 134.51 | 0.26 | 5.29 |

| CZMNZA | 99.95 | 0.20 | 5.70 |

| SBA-15 | 695.48 | 1.01 | 5.71 |

| CZMNZS | 319.79 | 0.73 | 7.86 |

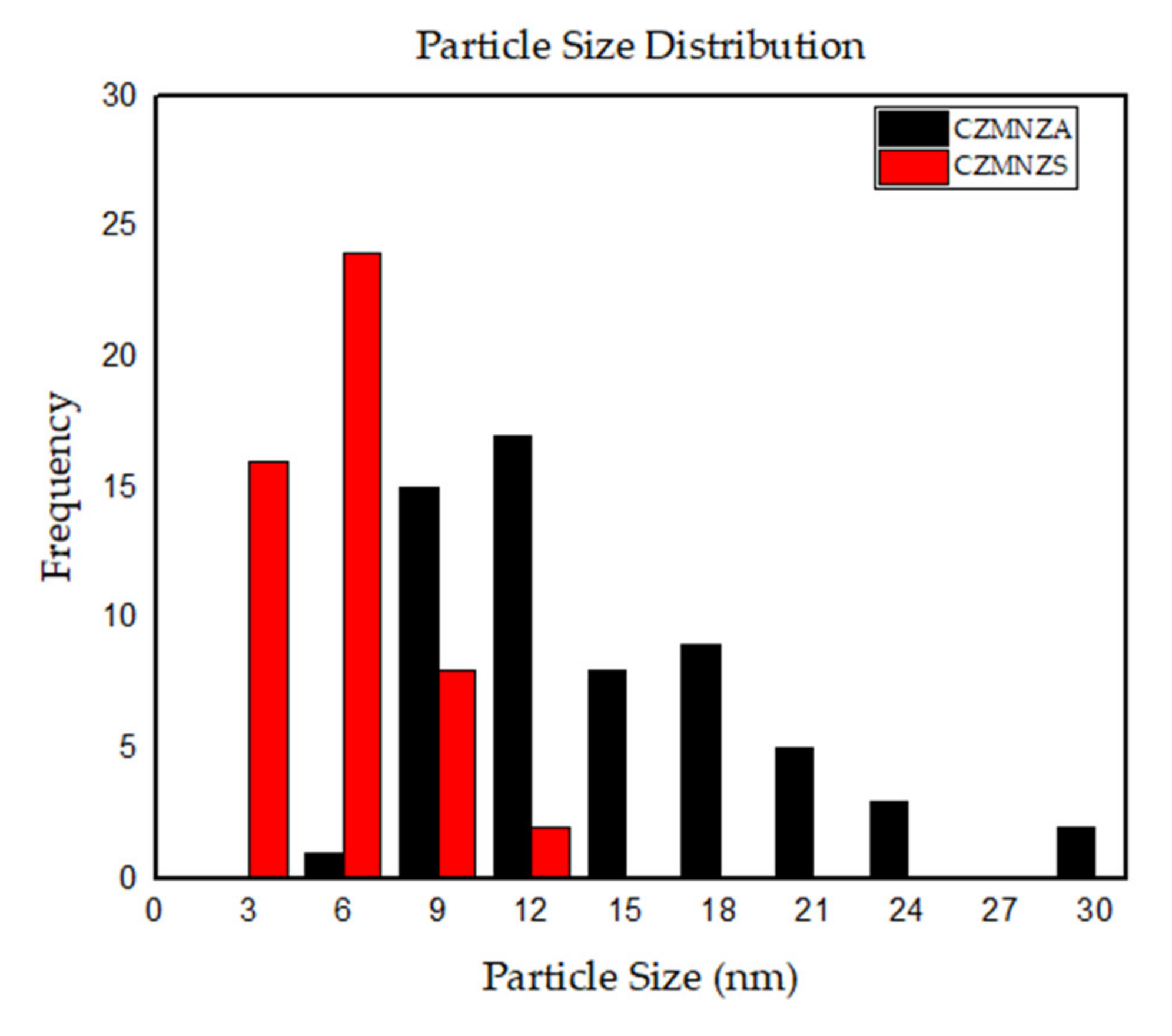

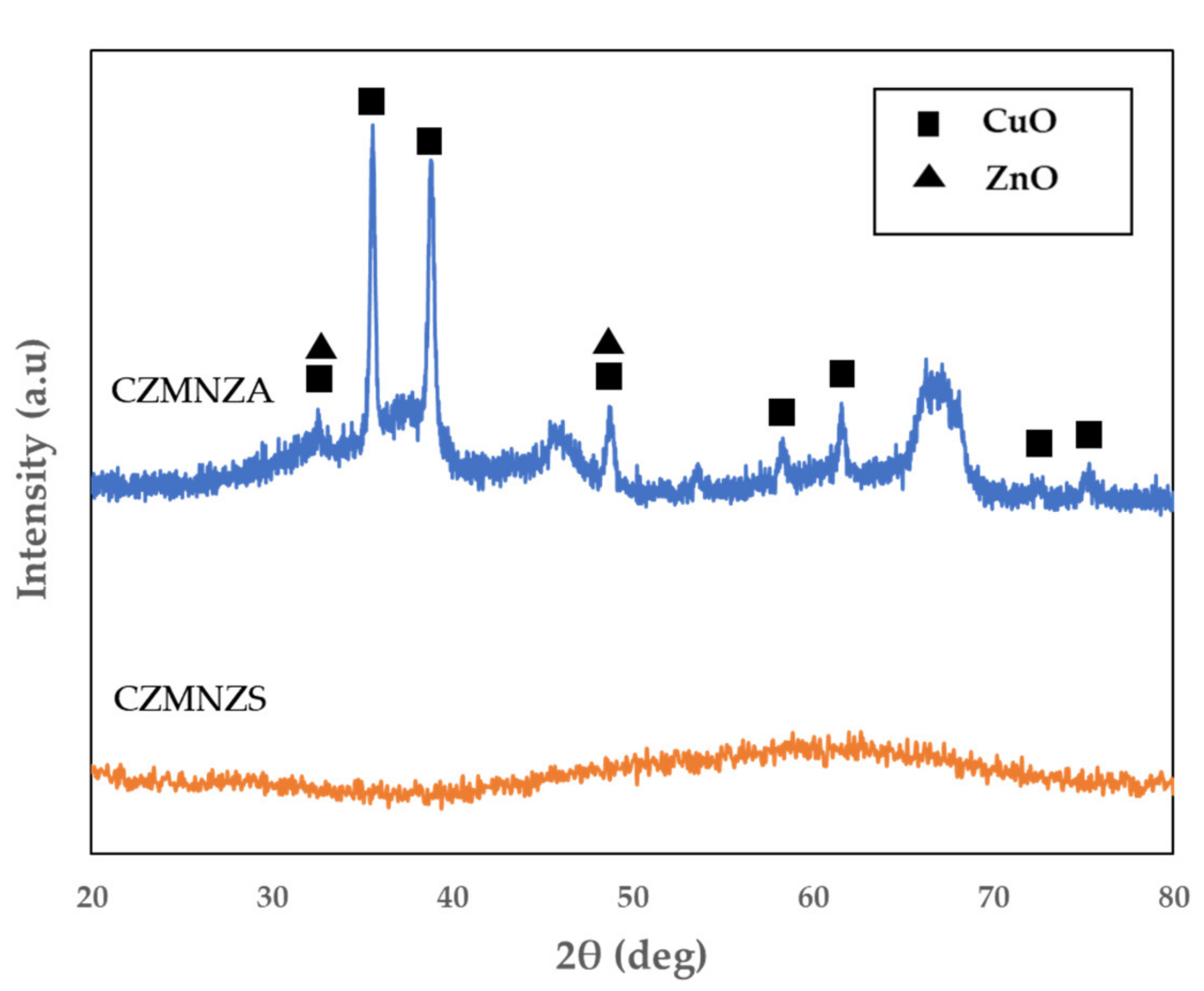

| Sample | Average Particle Size (nm) |

|---|---|

| CZMNZA | 16.00 ± 8.00 |

| CZMNZS | 6.09 ± 2.37 |

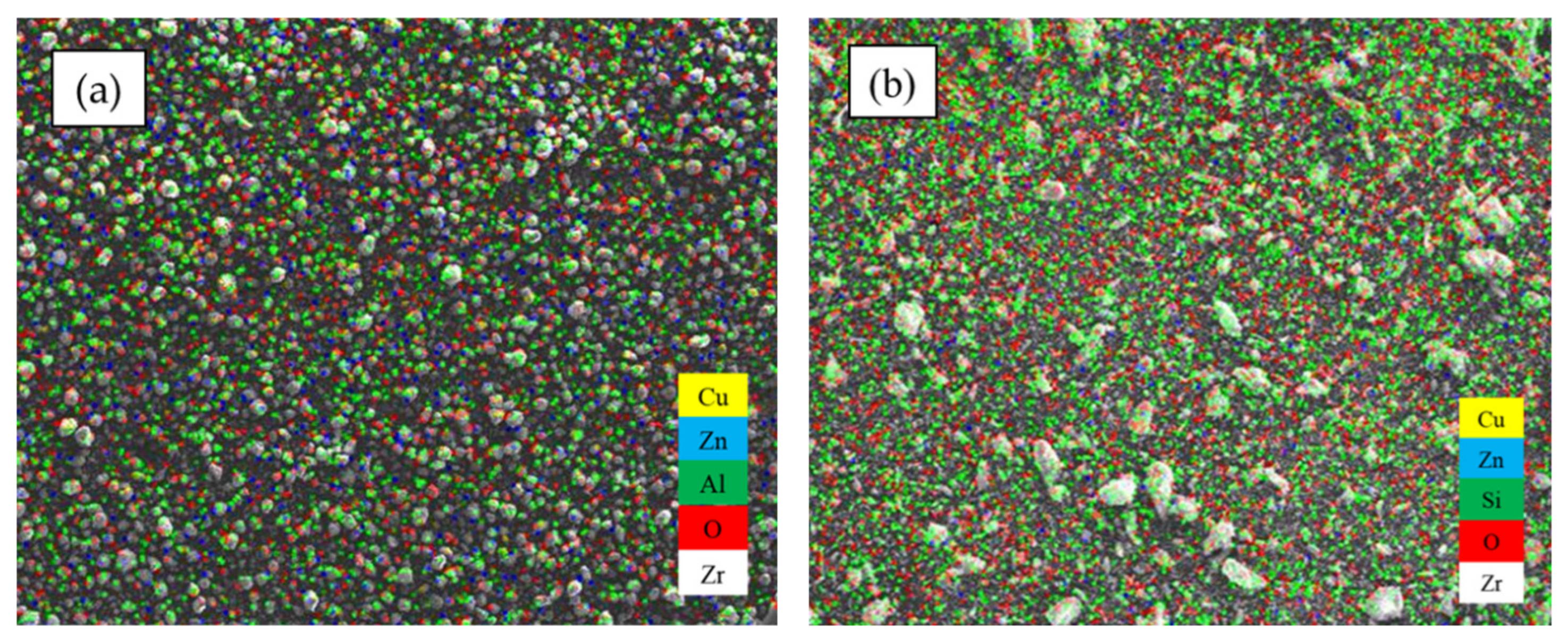

| Catalyst | Atomic Composition (%) | Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Zn | Mn | Nb | Zr | Cu/Zn | |

| CZMNZA | 5.24 | 7.36 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.71 |

| CZMNZS | 8.07 | 5.95 | 1.93 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 1.36 |

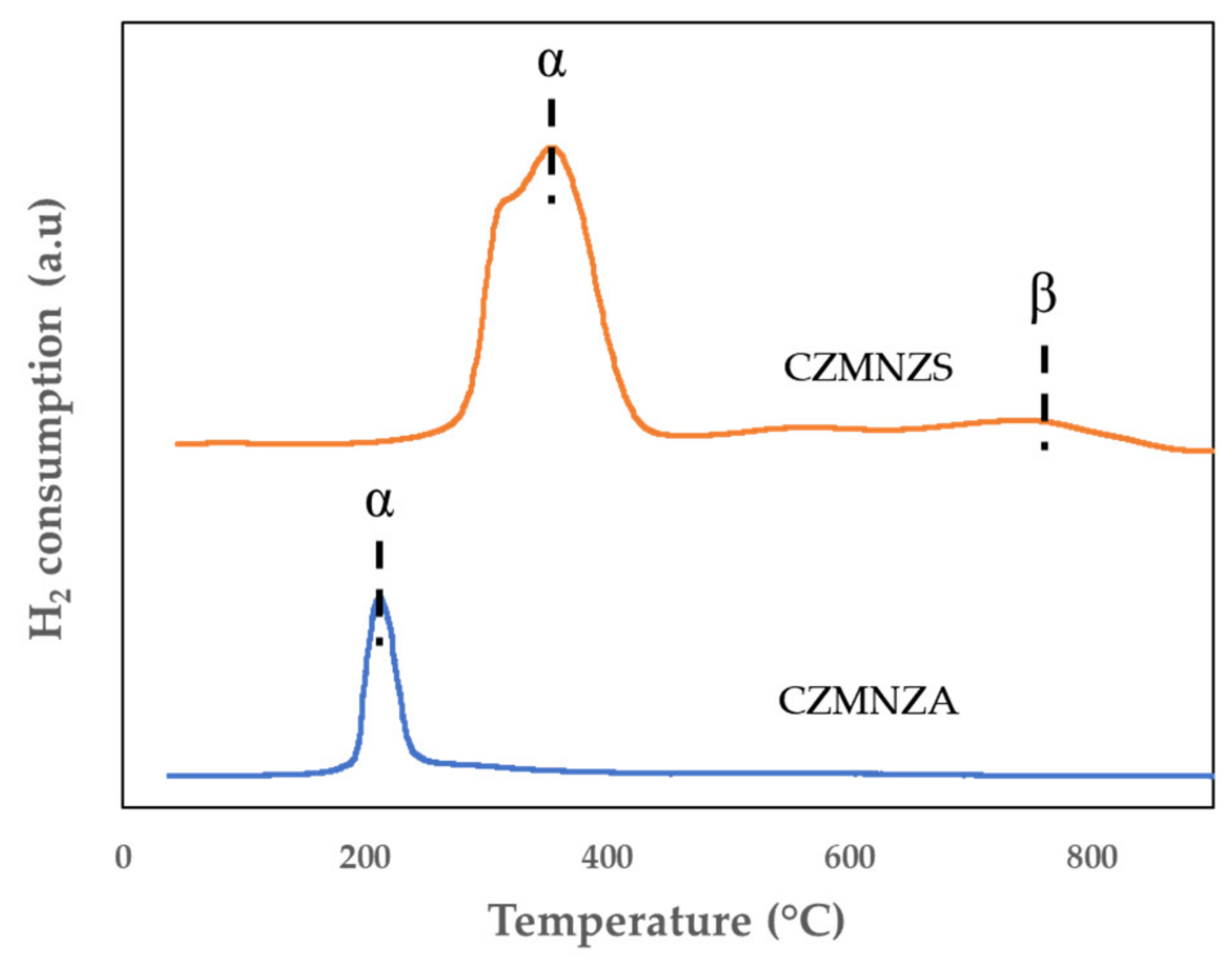

| Catalyst | Reduction Temperature (°C) | Total H2 Consumption (μmol/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CZMNZA | 213 | 717 | |

| α | β | ||

| CZMNZS | 355 | 743 | 2329 |

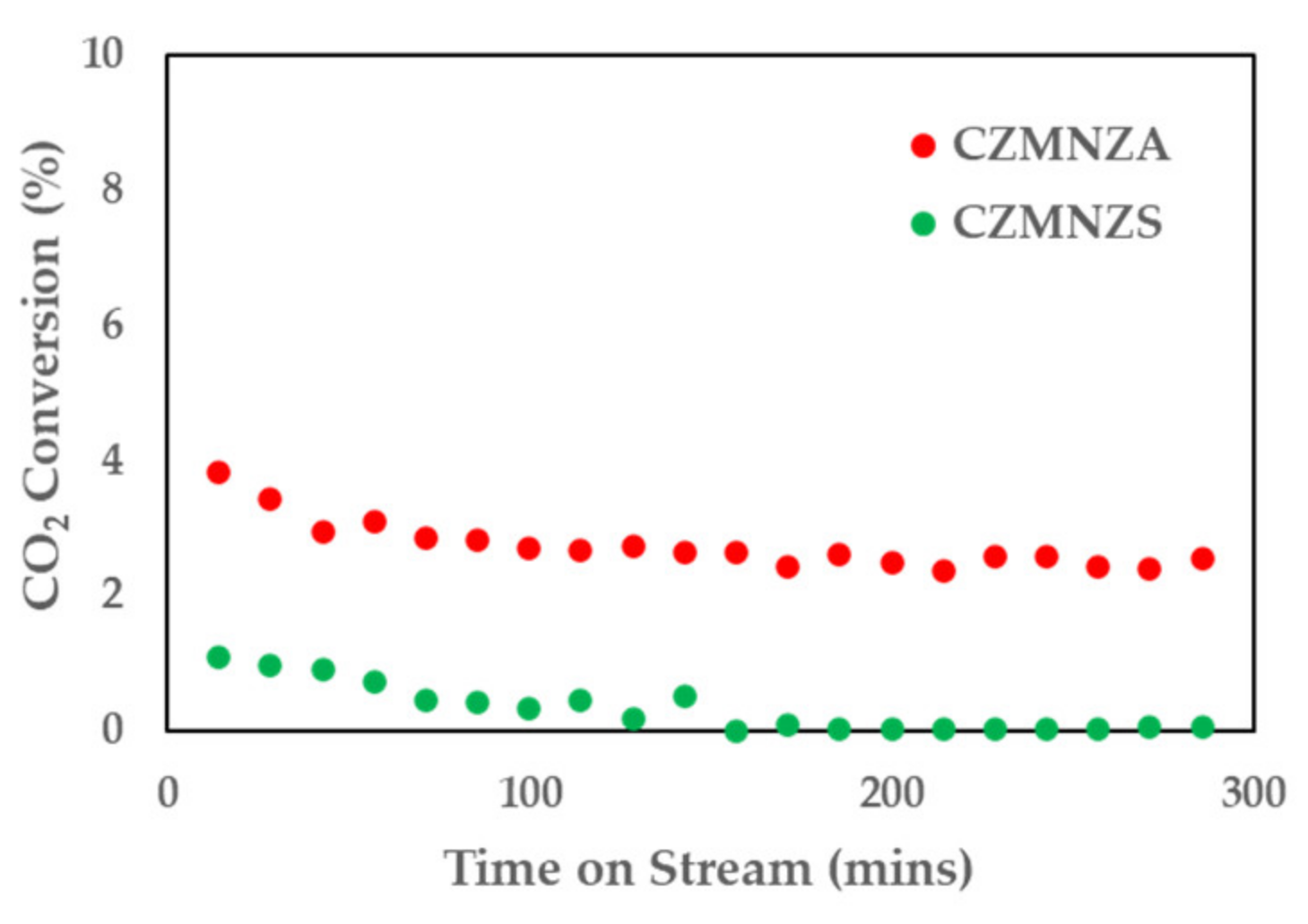

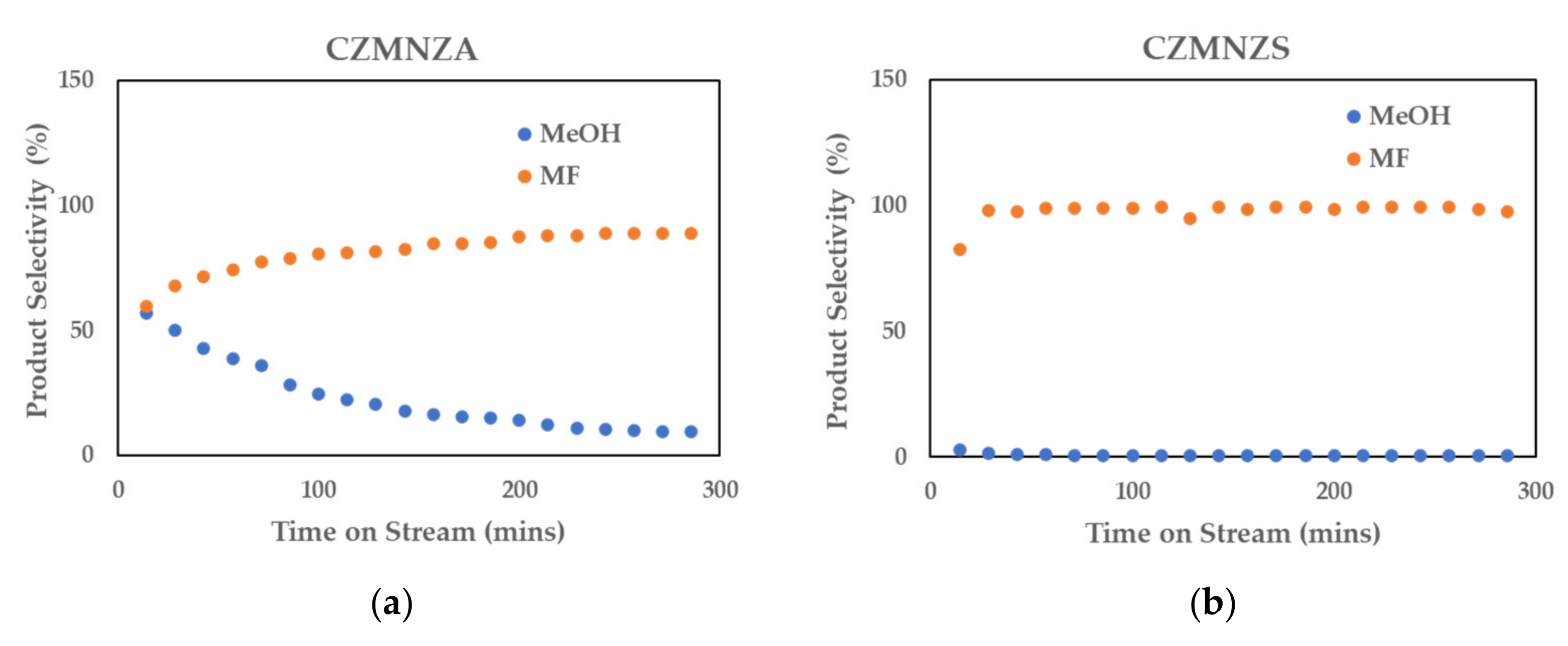

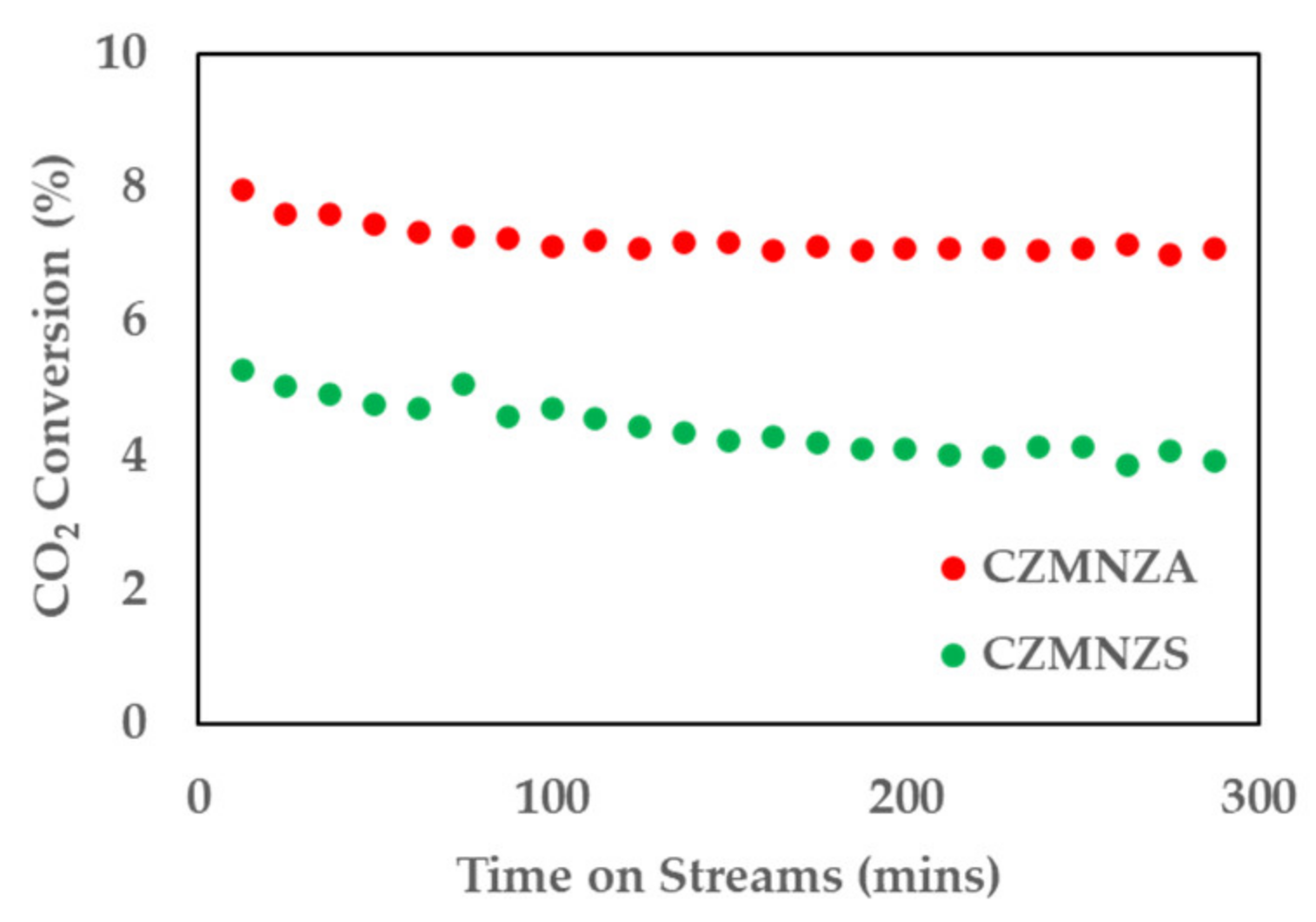

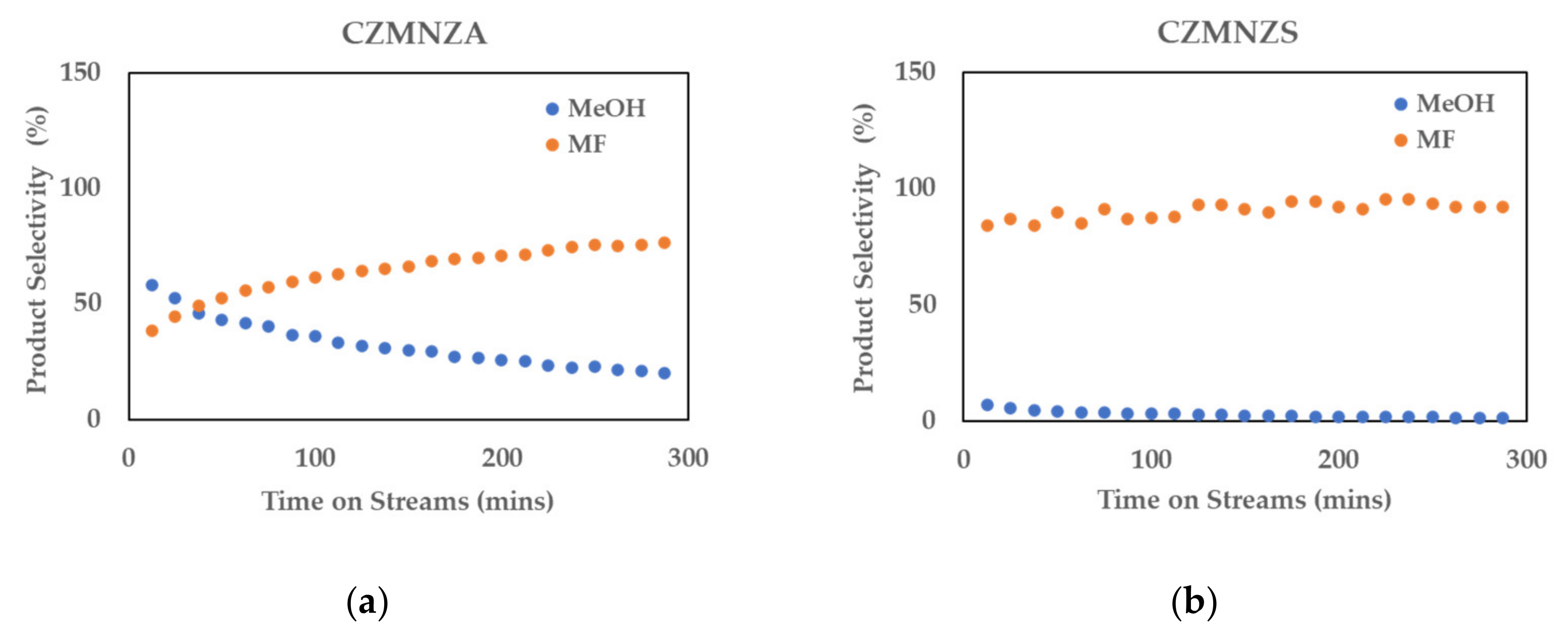

| Catalyst | CO2 Conversion * (%) | Product Selectivity * (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeOH | CH4 | MF | EtOH | ||

| CZMNZA | 7.22 | 32.10 | - | 64.57 | 1.99 |

| CZMNZS | 4.39 | 2.60 | - | 91.65 | 5.74 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berahim, N.H.; Mohd Zabidi, N.A.; Suhaimi, N.A. Co-Production of Methanol and Methyl Formate via Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 over Promoted Cu/ZnO Catalyst Supported on Al2O3 and SBA-15. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12091018

Berahim NH, Mohd Zabidi NA, Suhaimi NA. Co-Production of Methanol and Methyl Formate via Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 over Promoted Cu/ZnO Catalyst Supported on Al2O3 and SBA-15. Catalysts. 2022; 12(9):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12091018

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerahim, Nor Hafizah, Noor Asmawati Mohd Zabidi, and Nur Amirah Suhaimi. 2022. "Co-Production of Methanol and Methyl Formate via Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 over Promoted Cu/ZnO Catalyst Supported on Al2O3 and SBA-15" Catalysts 12, no. 9: 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12091018

APA StyleBerahim, N. H., Mohd Zabidi, N. A., & Suhaimi, N. A. (2022). Co-Production of Methanol and Methyl Formate via Catalytic Hydrogenation of CO2 over Promoted Cu/ZnO Catalyst Supported on Al2O3 and SBA-15. Catalysts, 12(9), 1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12091018