The survey was completed by 100 respondents from 20 universities (both private and governmental) offering architecture and interior design programs. The data provides insights into how these tools are perceived and used in design education in Jordan. Taking into account that the number of universities contributing is 20 (13 with Architecture departments, 7 with Interior Design departments, and some universities offering both), the number of respondents per university was 5 respondents, bringing the total respondents participating in the study from the 20 universities to 100 respondents.

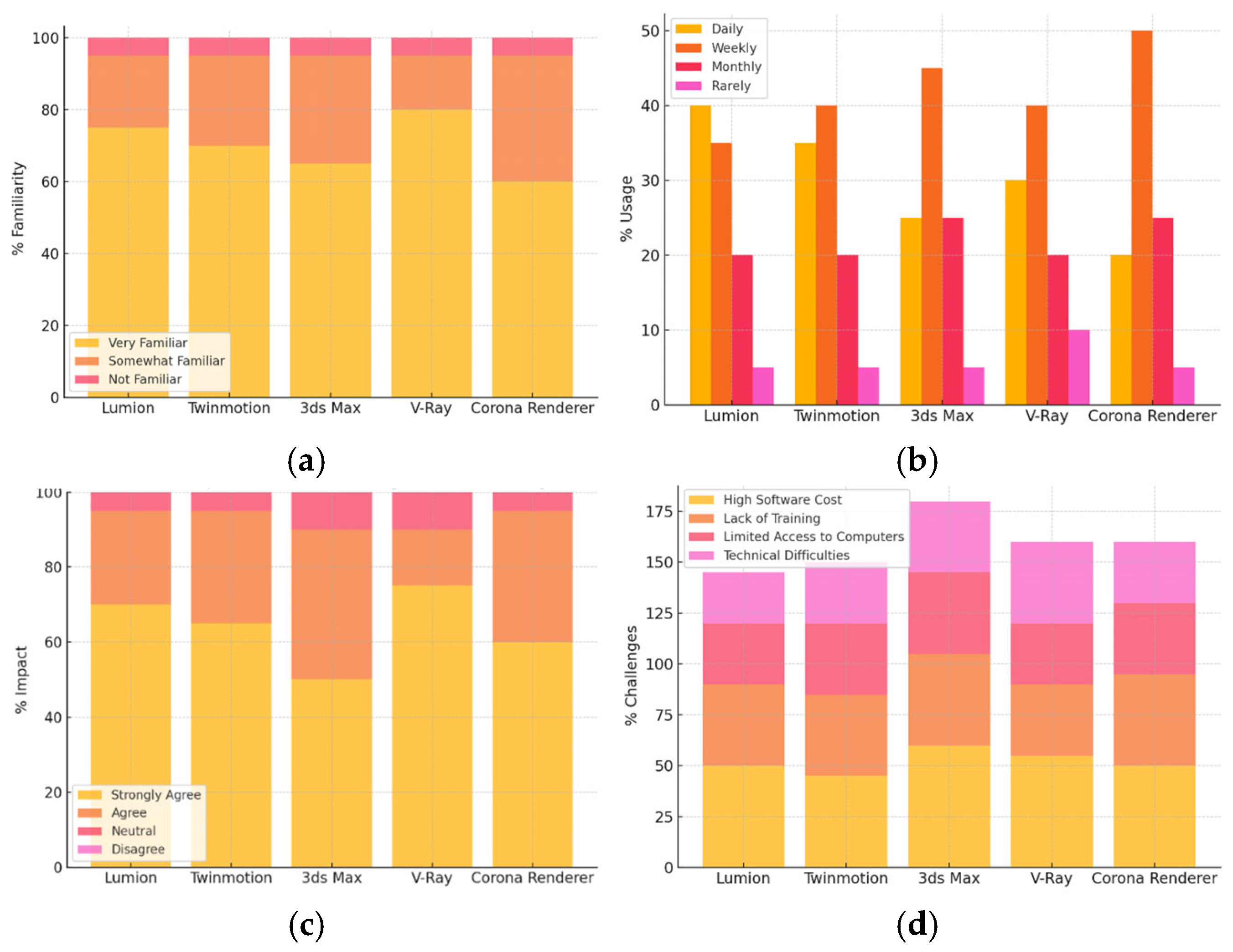

4.1. Data Analysis Results

The descriptive analysis Results Section is presented with the following structure for each of the eight categories:

Familiarity: Present the familiarity data, followed by the chart and its interpretation.

Usage Frequency: Present the usage frequency data, followed by the chart and its interpretation.

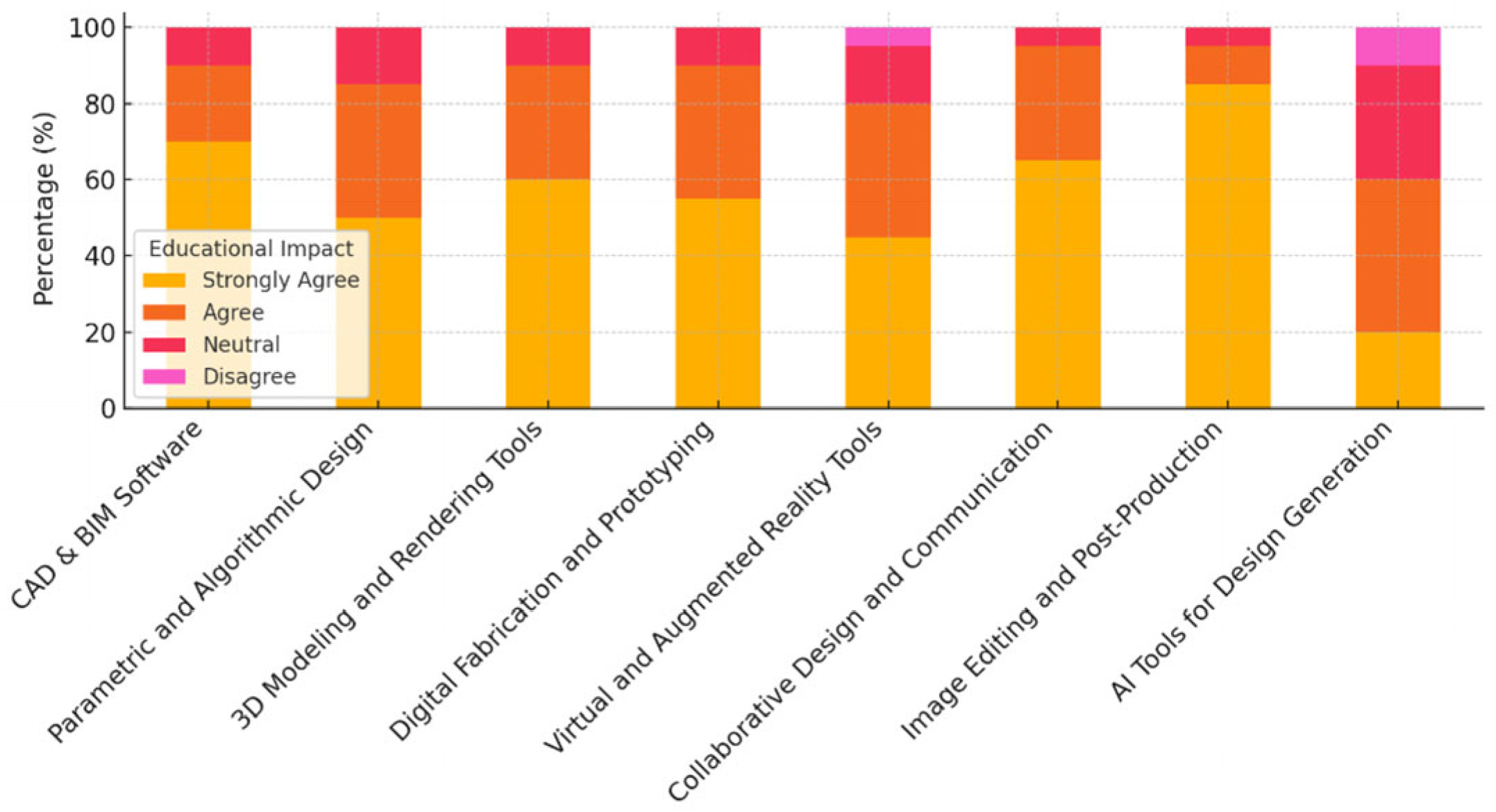

Educational Impact: Present the educational impact data, followed by the chart and its interpretation.

Challenges: Present the challenges data, followed by the chart and its interpretation.

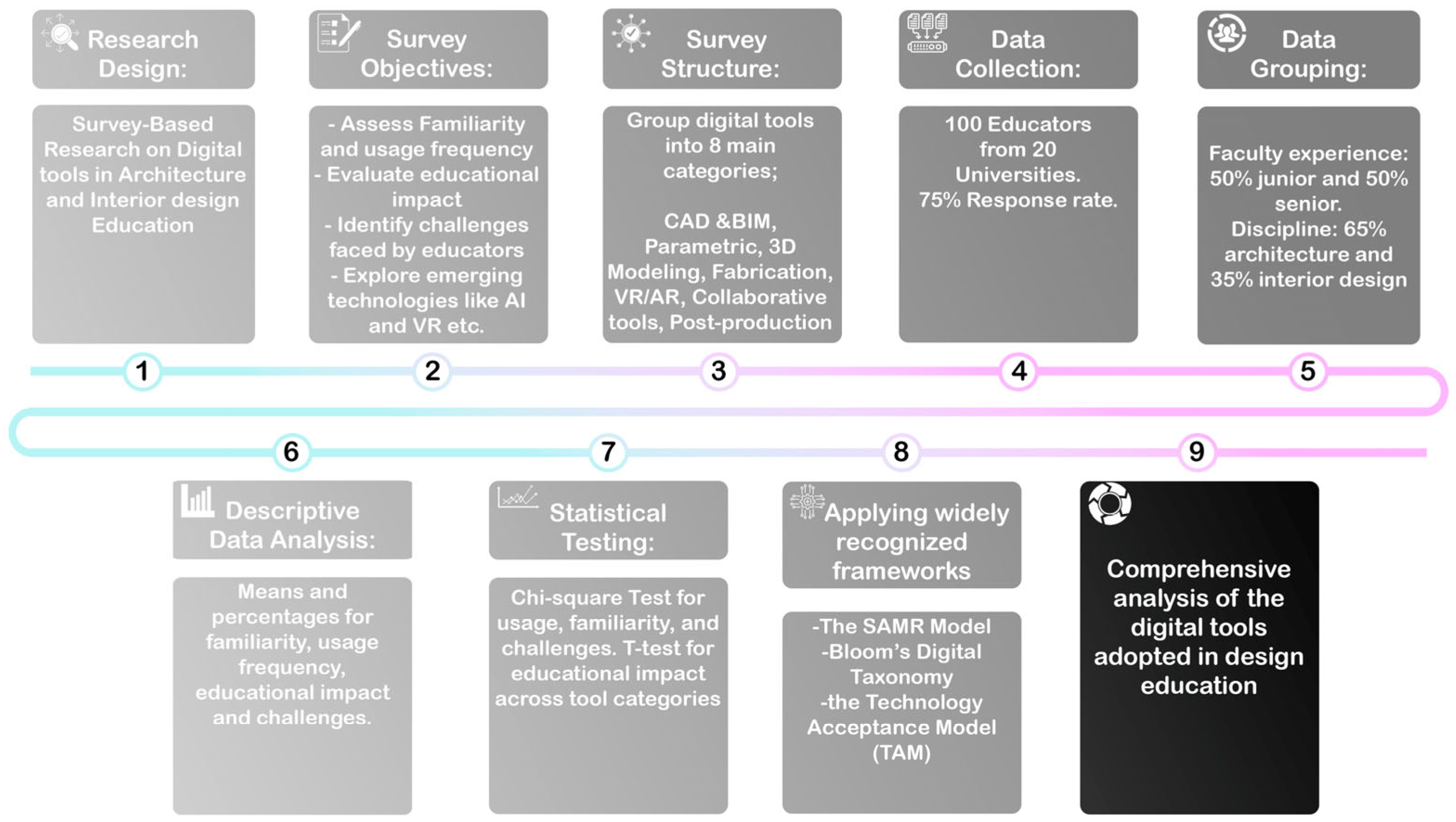

4.1.1. Results Section for the First Category; CAD/BIM Tools

- A.

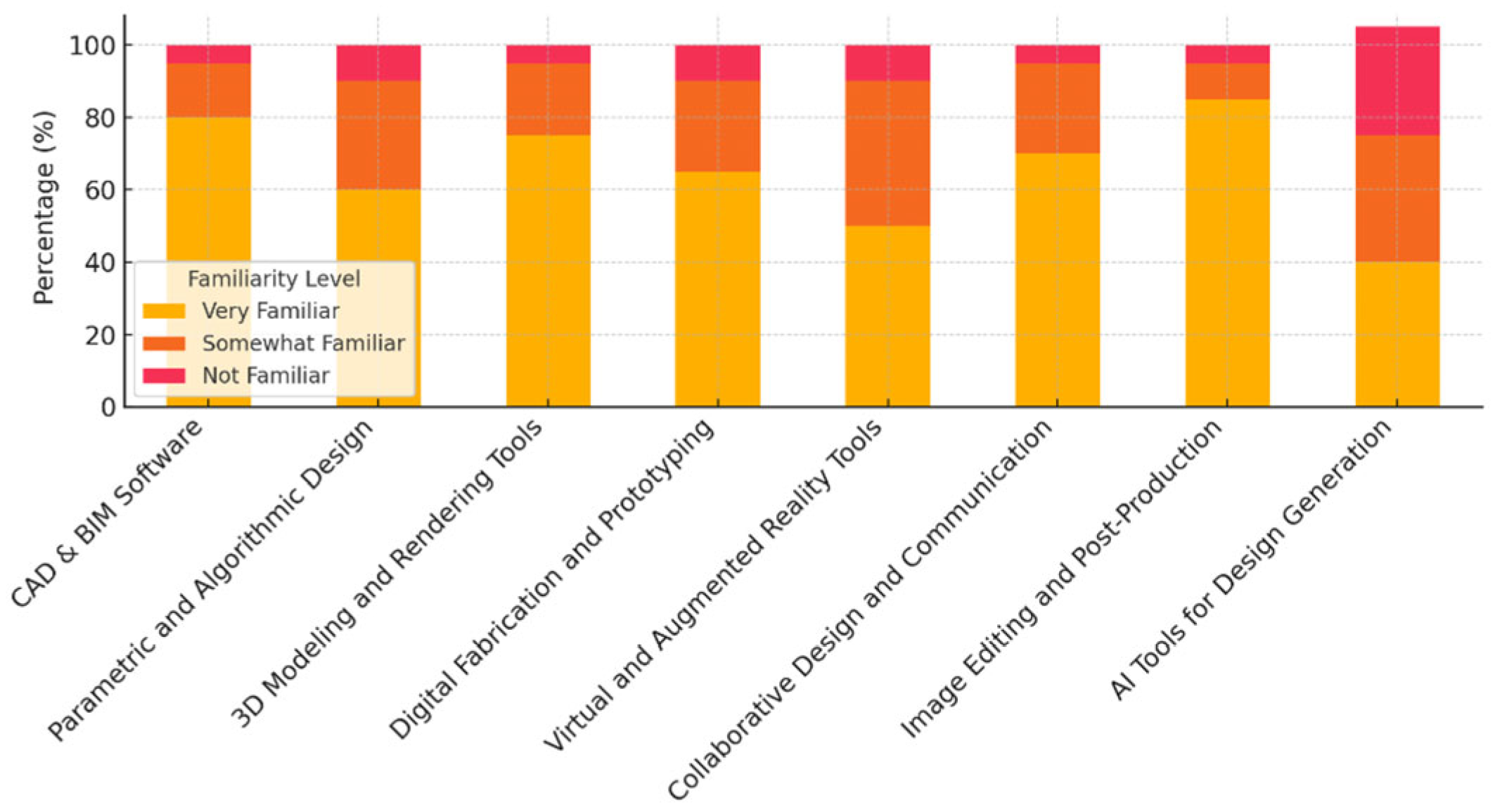

Familiarity with CAD/BIM Tools, as shown in

Table 1.

Results from this analysis show that AutoCAD and SketchUp have the highest familiarity, with 80% and 75% of respondents being very familiar with them, respectively. This indicates that these tools are well-established and commonly used in design education. While Revit and Archicad have lower familiarity levels (65% and 55%), suggesting that these tools are important but less universally recognized or adopted compared to AutoCAD. And finally, Rhino shows the lowest level of familiarity, with only 40% of respondents reporting high familiarity, possibly reflecting its more specialized use.

- B.

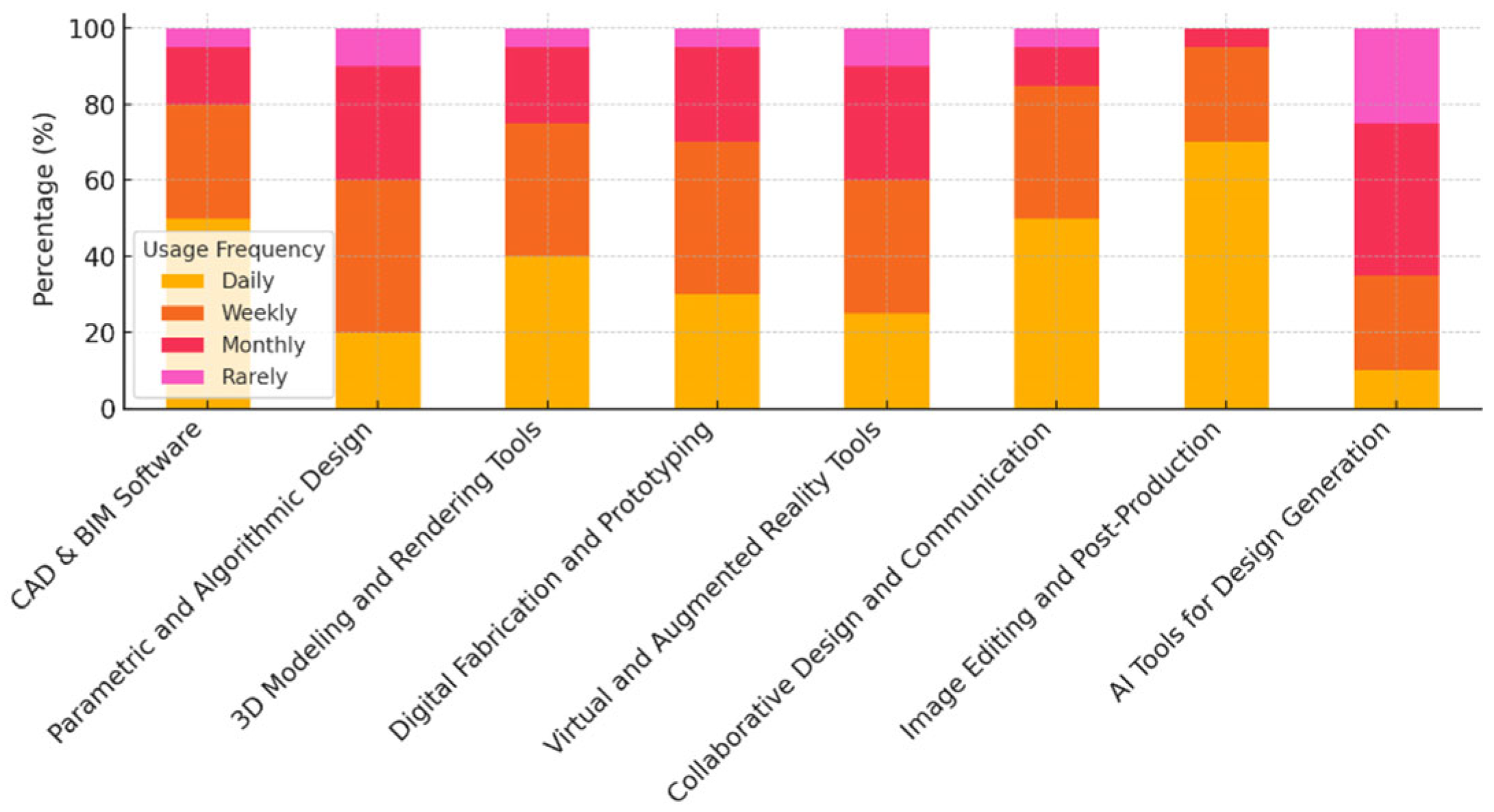

Usage Frequency of CAD/BIM Tools, as shown in

Table 2.

Results from this analysis show that SketchUp has the highest daily usage (60%), followed by AutoCAD (50%). These tools are used most frequently, suggesting their importance in daily design tasks. Revit shows moderate usage, with 25% of respondents using it daily and 40% using it weekly. This reflects its importance but indicates it may not be integrated into daily teaching. Meanwhile, Rhino and Archicad are used less frequently, with only 10% of respondents using Rhino daily. These tools are likely used for more specialized tasks and may require additional training or resources.

- C.

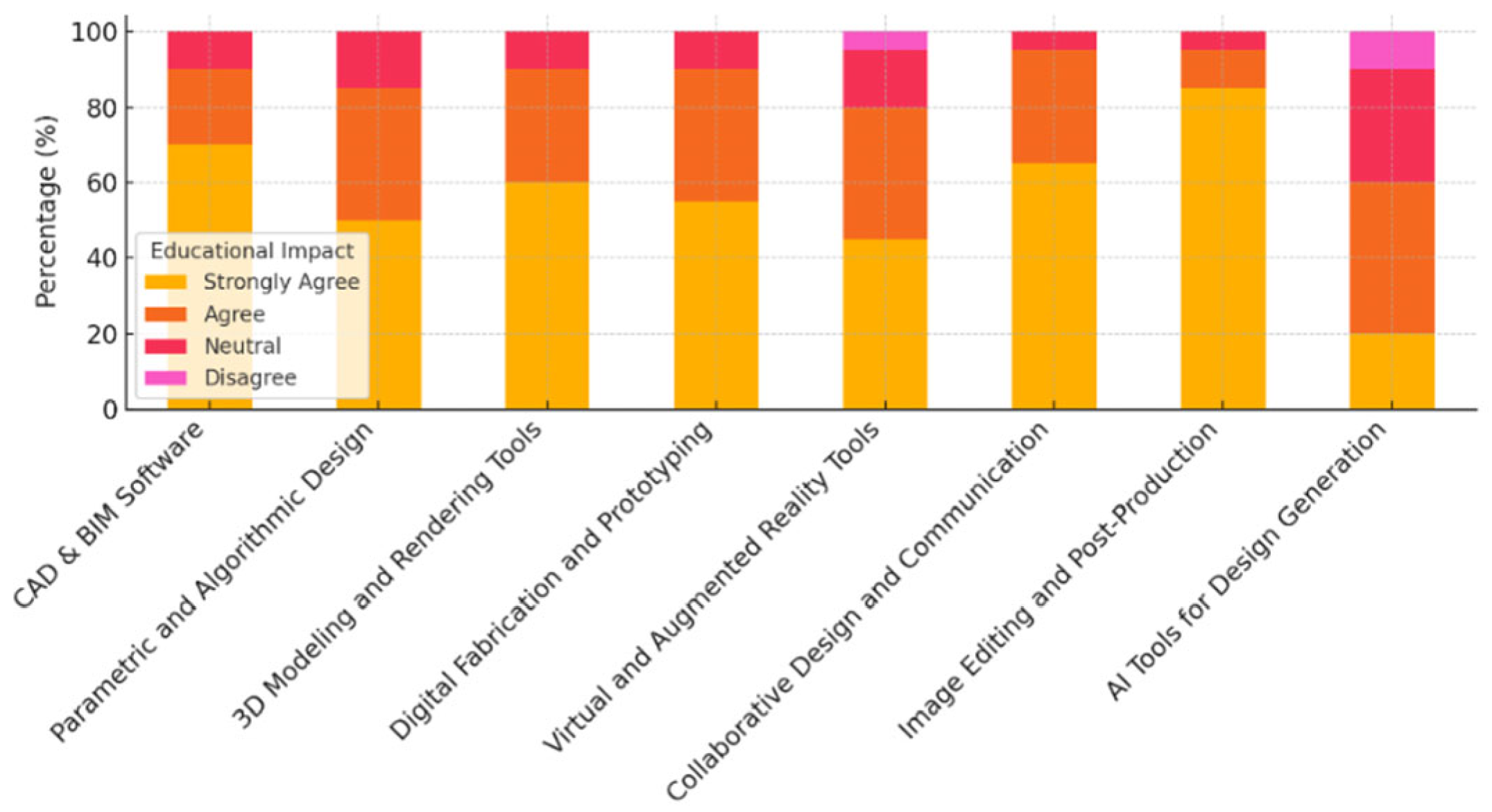

Educational Impact of CAD/BIM Tools, as shown in

Table 3.

Results from this analysis show that SketchUp has the highest positive impact, with 80% of educators strongly agreeing that it enhances student learning. Its ease of use and visualization capabilities make it an essential tool in design education. AutoCAD also shows a strong impact, with 70% strongly agreeing that it improves teaching and learning. Revit has a more mixed impact, with only 40% strongly agreeing. Given its complexity, educators may need more training to integrate it into teaching fully. And finally, Rhino shows a lower educational impact, with only 20% strongly agreeing. This could be due to its specialized nature and higher learning curve.

- D.

Challenges in Using CAD/BIM Tools, as shown in

Table 4.

Results from this analysis show that the most significant challenge reported for all tools is the high software cost (60%). This reflects the expensive licensing for professional design tools, which may limit access in educational institutions. Lack of training and limited access to computers were also significant barriers, especially for tools like Revit and Rhino that require specialized hardware and expertise. Technical difficulties were less common but still notable for tools like Rhino (35%) and Revit (30%), possibly indicating the complexity of these tools.

The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the first category, CAD/BIM tools, as shown in

Figure 2.

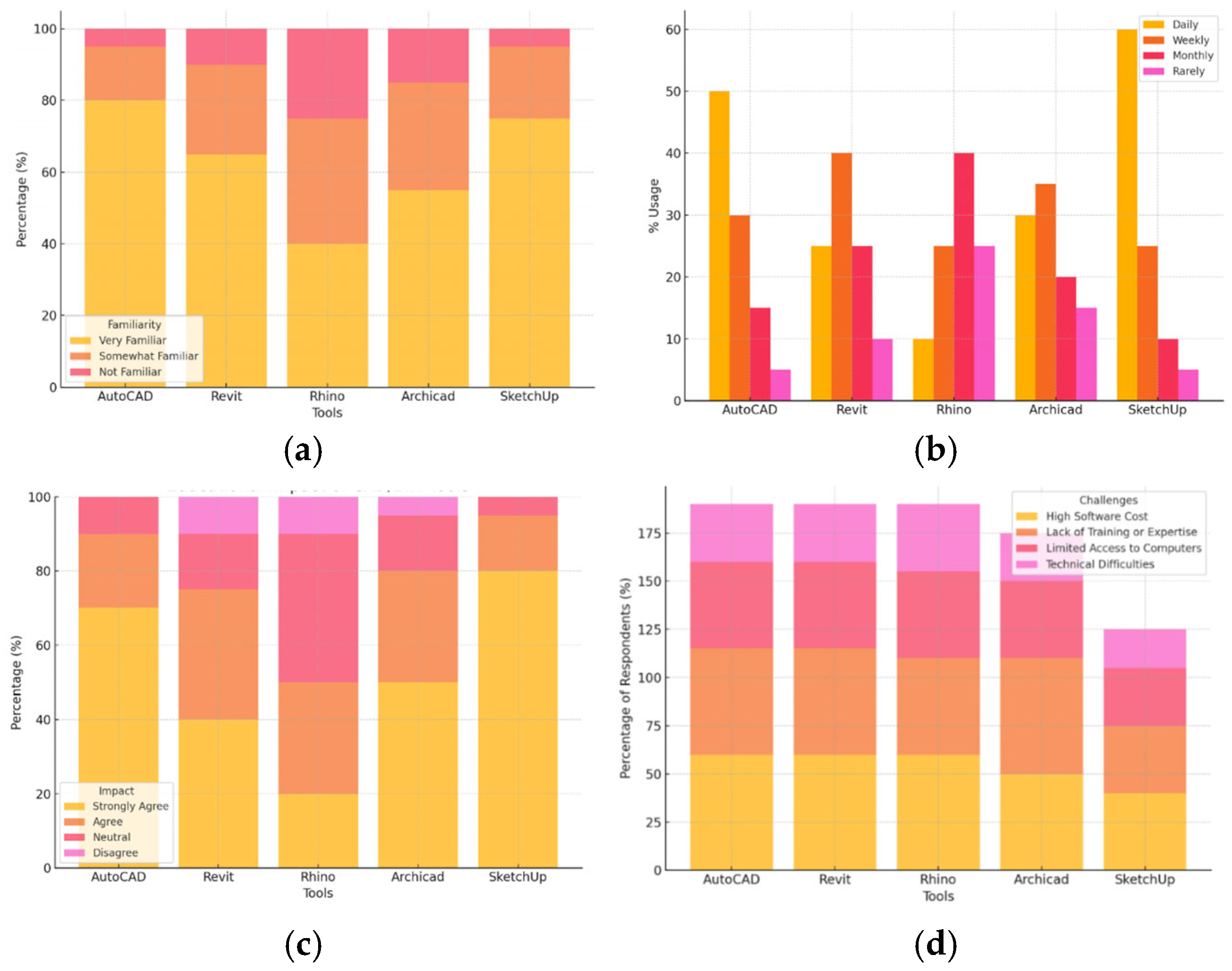

4.1.2. Results Section for the Second Category; Parametric and Algorithmic Design Software

- A.

Familiarity with Parametric and Algorithmic Design Software, as shown in

Table 5.

Results from this analysis show that Grasshopper (for Rhino) has the highest familiarity, with 70% of respondents being very familiar with it. This is consistent with its widespread use in architectural and design education, especially in programs that focus on parametric design. Dynamo (for Revit) shows a moderate level of familiarity, with 50% of respondents reporting that they are very familiar with it. Dynamo is used in BIM workflows but is not as universally known as Grasshopper, reflecting its specialized application. Houdini and TouchDesigner have lower familiarity levels, with 30% and 20% of respondents being very familiar with them, respectively. These tools are more specialized for advanced design and animation, which may explain their lower adoption rate in standard design curricula.

- B.

Usage Frequency of Parametric and Algorithmic Design Software, as shown in

Table 6.

Results from this analysis show that Grasshopper is the most commonly used tool on a daily basis, with 40% of respondents using it regularly. This highlights Grasshopper’s importance in design education, particularly in courses focused on parametric design and computational design methods. Dynamo is used more moderately, with 20% of respondents using it daily. This suggests that while Dynamo is important in BIM environments, it may not be as frequently used as Grasshopper in non-BIM-focused design curricula. Houdini and TouchDesigner have much lower daily usage, with 10% and 5% of respondents using them daily, respectively. These tools are likely reserved for more advanced, specialized design courses and are not yet integrated into the core curriculum for most design programs.

- C.

Educational Impact of Parametric and Algorithmic Design Software, as shown in

Table 7.

Results from this analysis show that Grasshopper shows the strongest educational impact, with 60% of respondents strongly agreeing that it enhances teaching and learning. Its integration with Rhino allows for rapid design exploration and facilitates computational thinking, making it a powerful educational tool in design studios. Dynamo also shows a positive impact, with 40% of respondents strongly agreeing that it improves education. As a tool for integrating design and BIM workflows, it has a strong educational impact, particularly for students learning BIM processes. Houdini and TouchDesigner have lower perceived educational impact, with only 25% and 15% strongly agreeing, respectively. While these tools are powerful for 3D modeling and animation, they are more specialized and may not have widespread educational application in general design programs.

- D.

Challenges in Using Parametric and Algorithmic Design Software, as shown in

Table 8.

Results from this analysis shows that high software cost is the most common challenge, reported by 60% of respondents across all tools. This highlights the barrier that the high cost of professional-grade software (like Rhino, Revit, Houdini, etc.) can have in limiting access to these tools, especially in institutions with constrained budgets. Lack of training is the second most common challenge, with 55% of respondents citing it, particularly for more advanced tools like Houdini and TouchDesigner. This indicates that even when tools are available, educators may lack the resources or expertise to teach them effectively. Limited access to computers is also an important challenge, reported by 45% of respondents, reflecting the fact that some of these tools require significant computational power, which may not be available in all institutions. Technical difficulties are reported by 40% of respondents, particularly for TouchDesigner and Houdini, which may be more complex to use and integrate into educational curricula.

The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Second Category, Parametric and Algorithmic Design Software, as shown in

Figure 3.

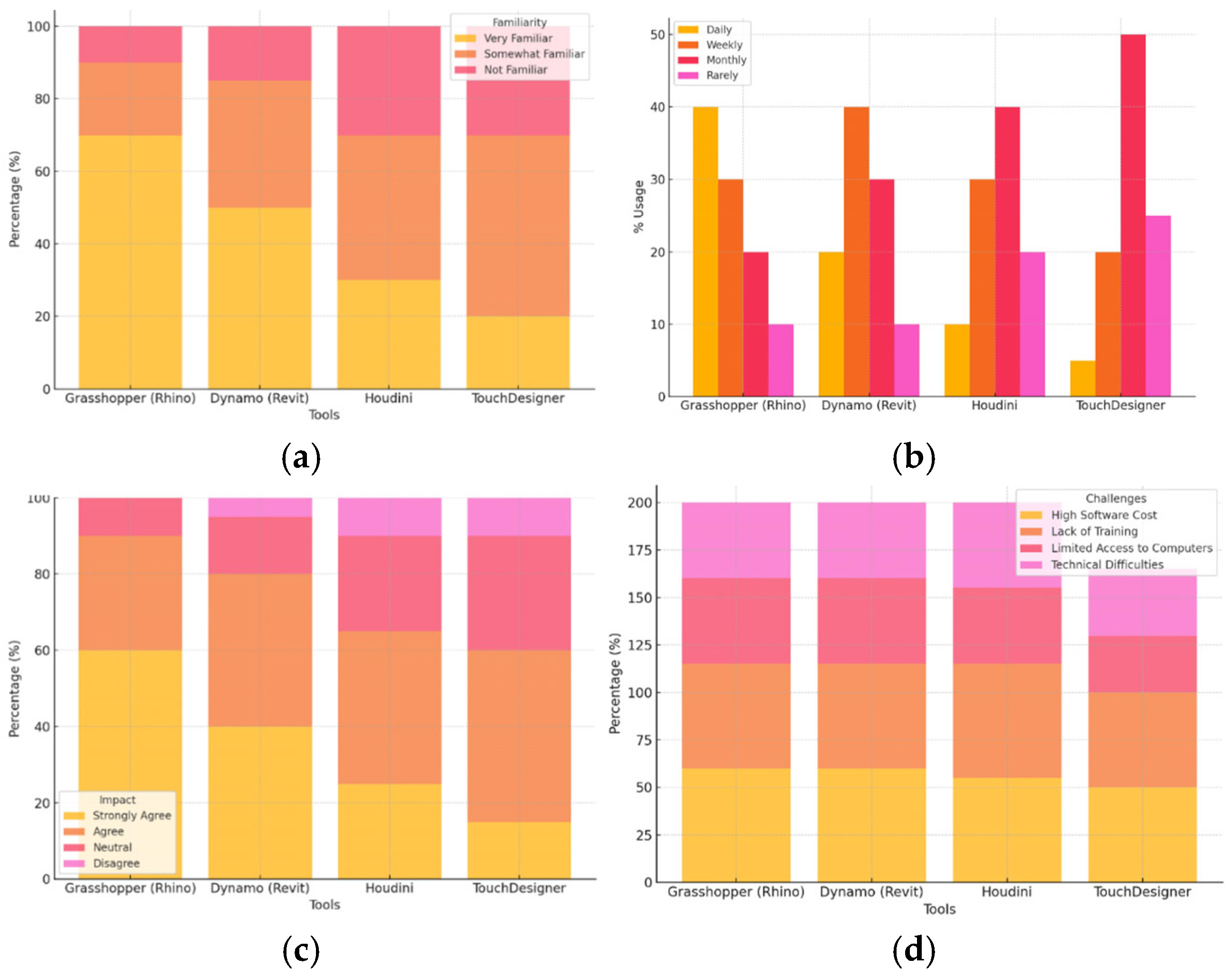

4.1.3. Results Section for the Third Category; 3D Modeling and Rendering Tools

- A.

Familiarity with 3D Modeling and Rendering Tools, as shown in

Table 9.

Results from this analysis show that V-Ray is the most familiar tool, with 80% of respondents reporting being very familiar with it. This reflects its widespread use in design education and industry for rendering purposes. Lumion and Twinmotion also have high familiarity rates, with 75% and 70% of respondents being very familiar, respectively. These tools are popular for their user-friendly interfaces and real-time rendering capabilities. 3ds Max shows moderate familiarity, with 65% reporting a high level of familiarity. While it is widely used in professional design settings, it may be less commonly incorporated into design education compared to tools like V-Ray. Corona Renderer has the lowest familiarity at 60%, though still relatively high. Its use in educational settings may be more recent or less prevalent than the other tools.

- B.

Usage Frequency of 3D Modeling and Rendering Tools, as shown in

Table 10.

The analysis shows that Lumion and Twinmotion have the highest percentage of daily usage, with 40 percent and 35 percent of the respondents, respectively, indicating that they use the tools daily. They are effective because of their fast-processing speeds and user-friendly interfaces, which ensure that realistic visualizations are produced. Three-de-eight-seo (3ds 3Ds Max) shows moderate usage or 25 percent of respondents; its relatively complex nature could restrict its ease of use in everyday classroom use by some individuals. The frequency of V-Ray and Corona Renderer is utilized at a lower rate on a daily basis, with the daily use reported at 30, indicating that people use it daily, and 20 say that they use it daily. These are also highly specialized applications, with the workflow of producing high-quality rendering often requiring more time and computation capacity to produce detailed visualization.

- C.

Educational Impact of 3D Modeling and Rendering Tools, as shown in

Table 11.

The same analytical framework reveals that V-Ray has an outstanding educational presence, with 75 percent of the respondents providing a high recommendation of effectiveness in the promotion of teaching and learning. The high fidelity and versatility of the tool make it a great asset in the design pedagogy. Lumion and Twinmotion also exhibit a high positive impact, with 70 percent and 65 percent of teachers confirming that they contribute to student learning, respectively. Their ability to provide real-time visualizations is particularly useful in enabling them to perform quick design iterations. Three-de-e-eight-seo is moderately positive; 50 percent of the respondents claim to agree with it strongly, but its complexity might require further training and practice, yet it provides advanced functionality to build complex 3D constructions. Corona Renderer has slightly less impact when compared to V-Ray, but is still positive, where 60 percent strongly agreed that it maximizes educational output. The high-quality design communication is supported by the photorealism of the tool.

- D.

Challenges in Using 3D Modeling and Rendering Tools, as shown in

Table 12.

Results from this analysis show that high software cost is the most significant challenge across all tools, with 60% of respondents reporting this challenge for 3ds Max. The high cost of professional software licenses is a common barrier to their widespread use in educational settings. Lack of training is also a notable challenge, particularly for tools like 3ds Max and Corona Renderer, where 45% of respondents report this barrier. This highlights the need for professional development and training to integrate these tools into curricula effectively. Limited access to computers is a challenge, especially for tools that require high-performance hardware, such as 3ds Max and V-Ray. Technical difficulties were less common but still notable, particularly for V-Ray, where 40% of educators reported challenges in handling the tool’s complex settings. The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Third Category: 3D Modeling and Rendering Tools, as shown in the charts in

Figure 4.

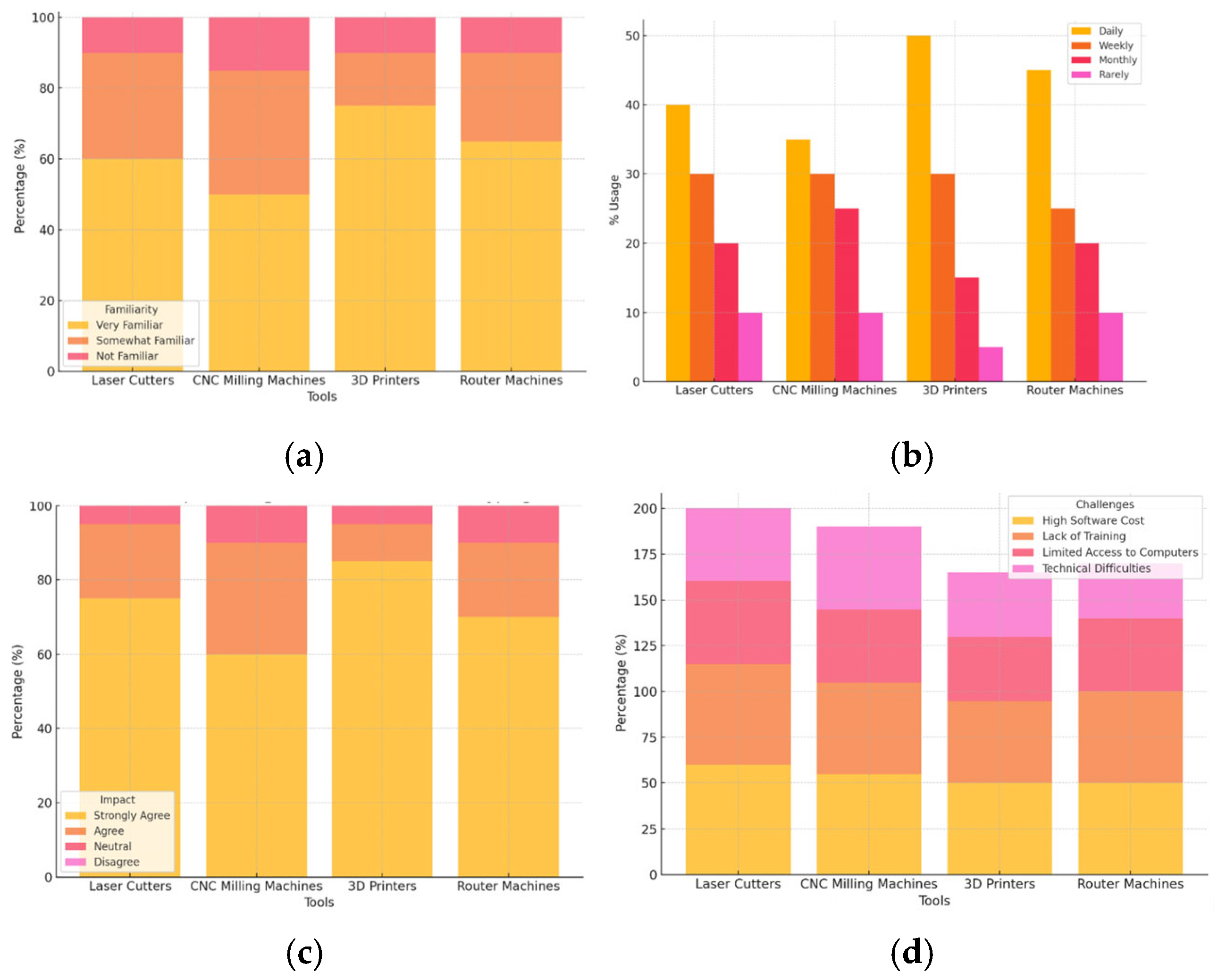

4.1.4. Results Section for the Fourth Category; Digital Fabrication and Prototyping Tools

- A.

Familiarity with Digital Fabrication and Prototyping Tools, as shown in

Table 13.

Regarding familiarity, the 3D printers have the most recognition, with 75% of respondents indicating high familiarity. This tool is widely used in academic and professional environments to prototype quickly and is becoming a part of design courses. The moderate familiarity is reached by laser cutters and router machines, which have the reported levels of 60 and 65%, respectively; these tools are predominantly used in the production of precise and detailed models, albeit with specialized knowledge. CNC milling machines are the least familiar, with 50% of the participants reporting a high familiarity. Although they are common in industrial and architectural fabrication, they are also not as commonly used in design education programs as 3D printers.

- B.

Usage Frequency of Digital Fabrication and Prototyping Tools, as shown in

Table 14.

Daily use analysis shows that 3D printers are the most used, with 50% of the respondents reporting daily usage. This trend indicates increased accessibility and teaching integration of 3D printing in design education for rapid prototyping. Laser cutters and router machines also demonstrate moderate usage with 40% and 45 percent daily use, respectively; these tools are necessary to make precise fabrication but are not used as often as 3D printers. CNC milling machines show the lowest usage per day, with 35 percent of the participants using the machines weekly, which indicates that their application is more associated with sophisticated fabrication operations than everyday teaching.

- C.

Educational Impact of Digital Fabrication and Prototyping Tools, as shown in

Table 15.

The last evaluation of educational impact signifies that the role of 3D printers has the strongest impact, with 85% of the respondents strongly supporting this as a tool to enhance teaching and learning. This was influenced by their versatility and continued spread to design education. Laser cutters and router machines also exhibit a positive effect, with 75% and 70% of respondents saying that the tools have improved learning outcomes, respectively. These tools are essential for accuracy work and may significantly enliven practical designing experiences. The influence of CNC milling machines is somewhat more uneven, with 60% of the respondents strongly agreeing that the machines might help in enhancing education, reflecting a more specialized use in the wider education spectrum.

- D.

Challenges in Using Digital Fabrication and Prototyping Tools, as shown in

Table 16.

The results show that high software cost is the main bottleneck in all digital fabrication tools, with laser cutters (60%) and CNC milling machines (55%) being the most vulnerable. Next in line is the lack of training, especially among laser cutters (55%) and CNC milling machines (50%), which demonstrates the need to have specific knowledge. Limited access to computing facilities affects all devices, but with a significant effect on 3D printers (35%), this further intensifies the need to have high-performance hardware. Although the technical complications are less common, they are still consequential, especially the router machines (30%), with the lowest rate of occurrence. The leading barriers that hinder the successful implementation of these technologies into design pedagogy include cost, training, and availability of resources, collectively.

The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Fourth Category, Digital Fabrication and Prototyping Tools, as shown in

Figure 5.

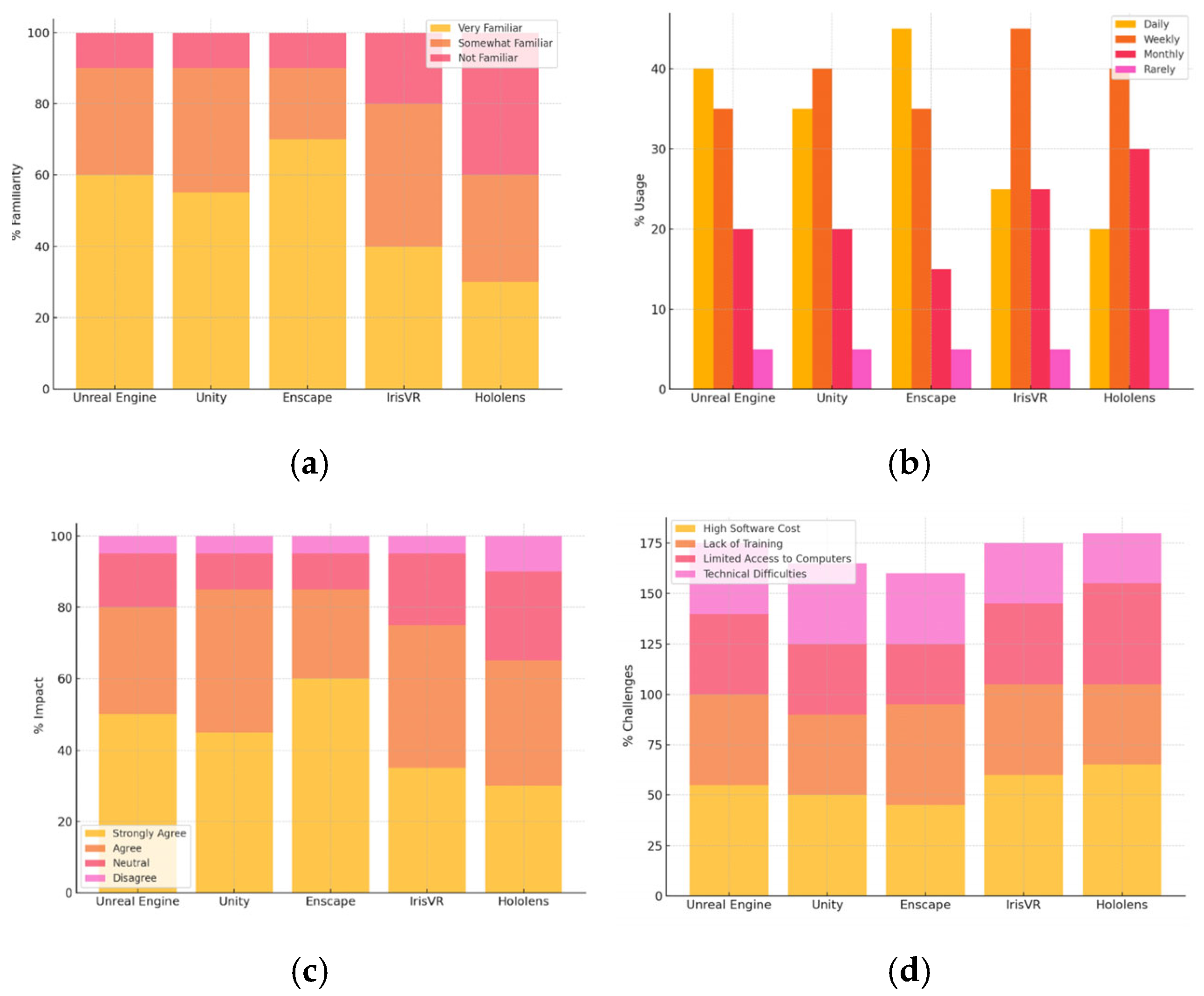

4.1.5. Results Section for the Fifth Category; Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools

- A.

Familiarity with Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools, as shown in

Table 17.

Results from this analysis show that Enscape is the most familiar tool, with 70% of respondents being very familiar with it. It is widely used in design education for immersive visualizations. Unreal Engine and Unity also have a strong familiarity rate of 60% and 55%, respectively. These tools are well-known for their interactive and immersive capabilities in design education. IrisVR and Hololens have lower familiarity levels, with 40% and 30% of respondents being very familiar. These tools are more specialized and may not yet be integrated into the core curricula of many design programs.

- B.

Usage Frequency of Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools, as shown in

Table 18.

Results from this analysis show that Enscape has the highest daily usage at 45%, followed by Unreal Engine and Unity at 40% and 35%, respectively. These tools are frequently used in design studios for immersive visualizations. IrisVR and Hololens are used less frequently, with 25% and 20% using them daily, indicating that these tools might be more specialized or used in specific courses. IrisVR and Hololens show relatively high weekly usage, with 45% and 40% using them regularly, indicating that they are still being integrated into the curriculum but with moderate frequency.

- C.

Educational Impact of Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools, as shown in

Table 19.

Results from this analysis show that Enscape has the highest positive impact, with 60% of educators strongly agreeing that it enhances teaching and learning. Its real-time rendering capabilities make it a powerful tool for design education. Unreal Engine and Unity also show strong educational impact, with 50% and 45% of educators strongly agreeing. These tools support immersive and interactive learning experiences. IrisVR and Hololens show a more mixed impact, with 35% and 30% strongly agreeing. While these tools are impactful for certain educational contexts, their specialized nature might limit their widespread application.

- D.

Challenges in Using Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools, as shown in

Table 20.

Results from this analysis show that high software cost is the most significant challenge across all tools, with 65% of respondents citing it for Hololens and 60% for IrisVR. The high cost of VR/AR hardware and software licenses is a common barrier in educational settings. Lack of training is also a major issue, with 50% of respondents citing it for Enscape. This suggests a need for more professional development and resources to fully integrate these tools into design education. Limited access to computers is a significant challenge, particularly for Hololens, with 50% of respondents indicating this as a barrier. VR/AR tools often require high-performance computers or specialized hardware, which may not be available in all institutions. Technical difficulties were reported by 35% of respondents for Unreal Engine and Unity, indicating that while these tools offer great potential, they may require more technical expertise to integrate into the curriculum effectively.

The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Fifth Category, Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools, as shown in

Figure 6.

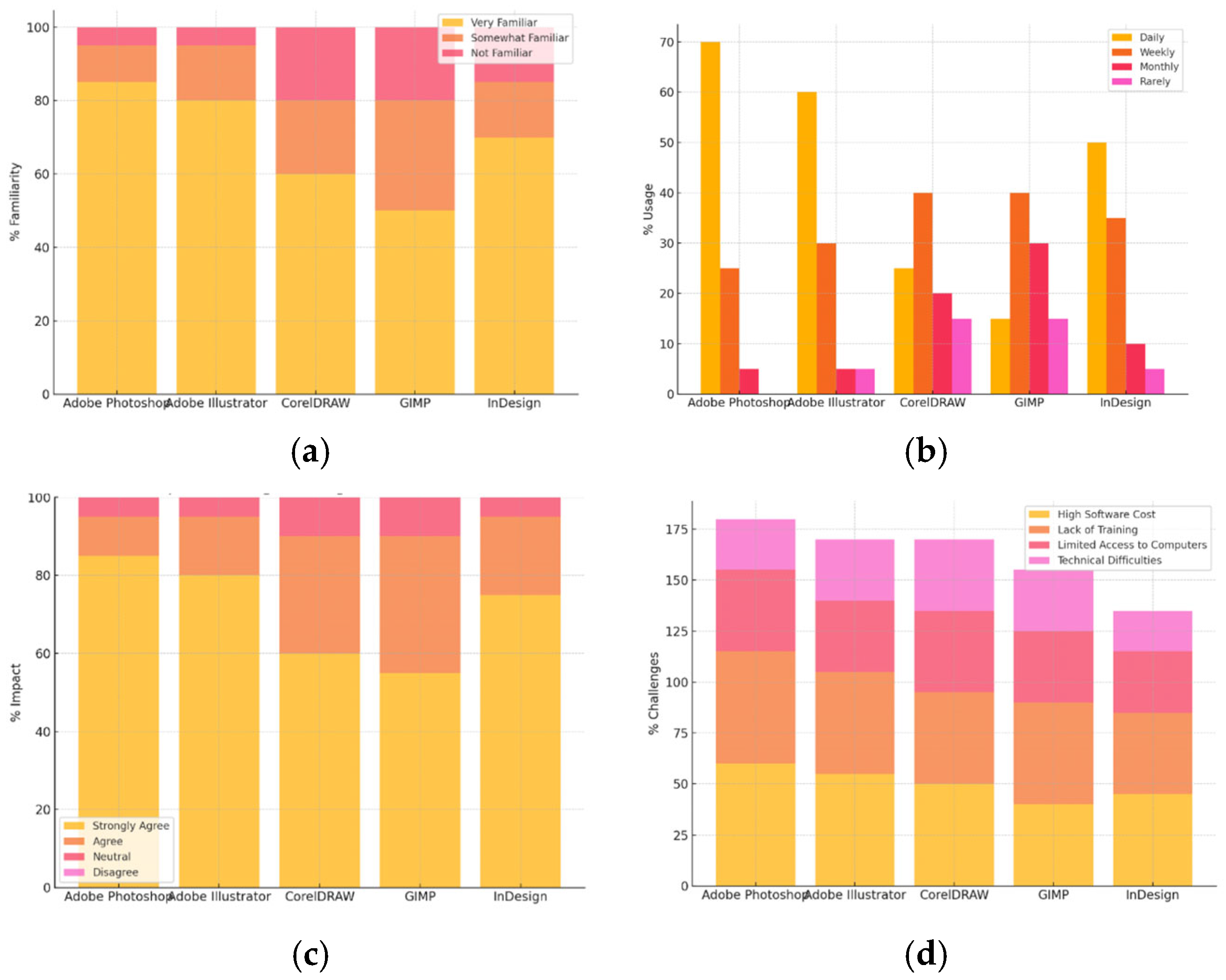

4.1.6. Results Section for the Sixth Category; Image Editing and Post-Production Tools

- A.

Familiarity with Image Editing and Post-Production Software, as shown in

Table 21.

Results from this analysis show that Adobe Photoshop is the most familiar tool, with 85% of respondents being very familiar with it. This reflects its widespread use in both professional design and educational settings for editing and enhancing visual content. Adobe Illustrator follows closely, with 80% of respondents being very familiar, confirming its significant role in vector graphic design. InDesign also shows high familiarity at 70%, as it is essential for layout design and final presentation work. CorelDRAW and GIMP have lower familiarity rates, with 60% and 50%, respectively, but still indicate solid usage in certain educational contexts, particularly in open-source environments (GIMP) and in traditional design settings (CorelDRAW).

- B.

Usage frequency of Image Editing and Post-Production Software, as shown in

Table 22.

The results of this survey show that 70% of the people who answered use Adobe Photoshop every day. This shows that it is an important part of design education for things like editing images, changing the way they look, and making them look better. Adobe Illustrator is also used a lot every day, at 60%, which makes sense because it is important for making designs and illustrations. Half of the people who answered said they use InDesign every day, which shows how important it is for layout and presentation design. CorelDRAW and GIMP are used less often every day, with 25% and 15% of users, respectively. However, both tools are still used a lot, especially in some specialized design courses or for open-source projects.

- C.

Educational Impact of Image Editing and Post-Production Software, as shown in

Table 23.

Results from this analysis show that Adobe Photoshop has the highest educational impact, with 85% of educators strongly agreeing that it enhances teaching and learning. Its role in image manipulation, retouching, and creating design assets makes it indispensable in design education. Adobe Illustrator follows closely, with 80% of respondents strongly agreeing about its positive impact, highlighting its effectiveness in vector-based graphic design. InDesign also has a strong educational impact, with 75% of respondents strongly agreeing that it helps in layout design and final presentation work. CorelDRAW and GIMP show moderate educational impact, with 60% and 55% strongly agreeing, indicating their relevance in some design curricula, particularly in more traditional or open-source contexts.

- D.

Challenges in Using Image Editing and Post-Production Software, as shown in

Table 24.

Results from this analysis show that high software cost is the most significant challenge for all tools, particularly for Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator, with 60% and 55% of respondents reporting it. The high cost of licensing for these industry-standard tools can be a barrier in educational environments, especially in institutions with limited budgets. Lack of training is a notable issue, reported by 55% of respondents for Photoshop and 50% for Illustrator, indicating that educators may need more professional development or resources to teach these tools effectively. Limited access to computers is a challenge for all tools, particularly for Photoshop, Illustrator, and CorelDRAW, where 40% to 60% of respondents reported this issue. These tools often require high-performance computers, which may not be available in all institutions. Technical difficulties were less common but still notable, especially for CorelDRAW and GIMP, where 35% and 30% of respondents cited this barrier. These issues may be related to compatibility or software setup.

The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Sixth Category, Image Editing and Post-Production Tools, as shown in

Figure 7.

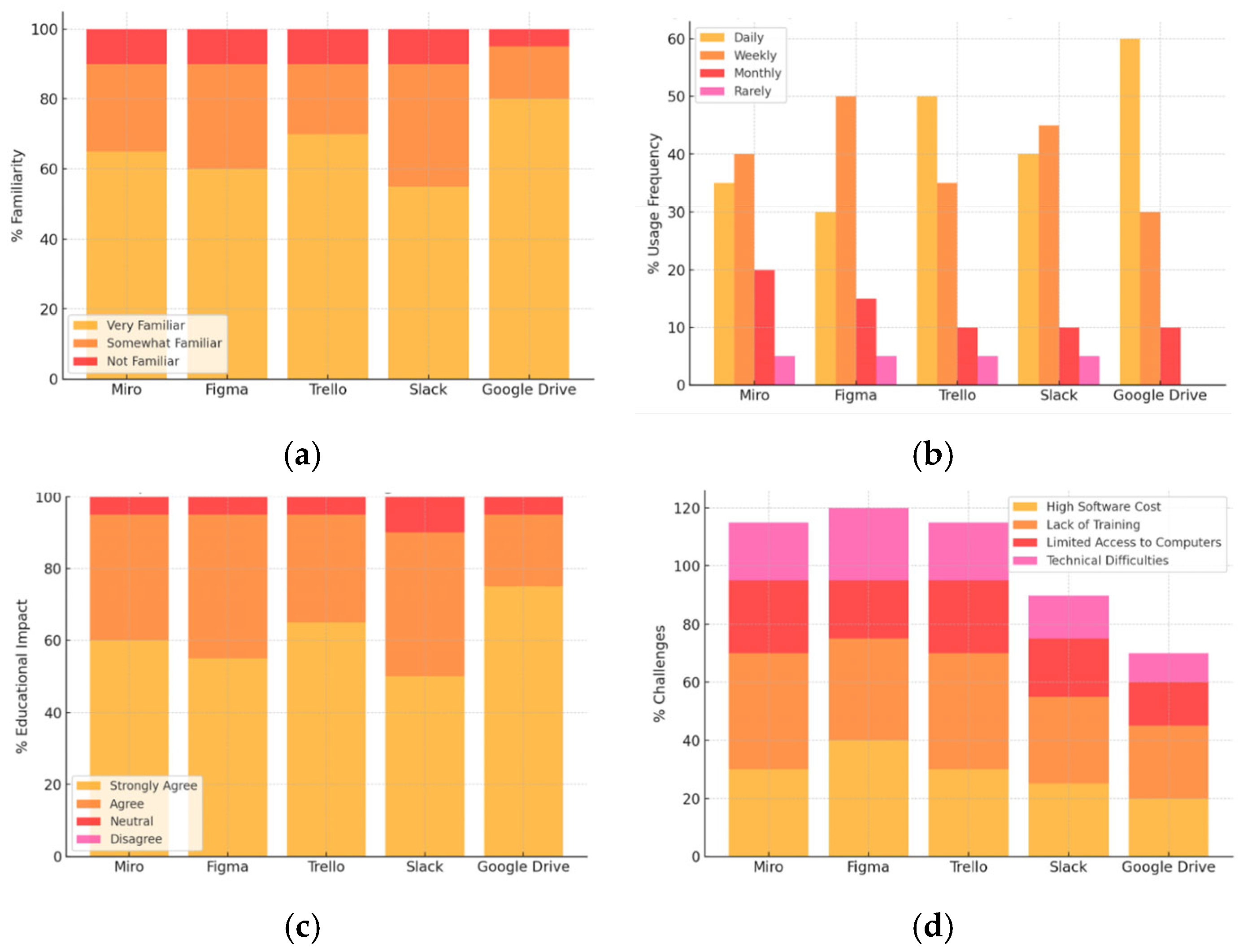

4.1.7. Results Section for the Seventh Category; Collaborative Design and Communication Tools

- A.

Familiarity with Collaborative Design and Communication Tools, as shown in

Table 25.

The familiarity data show a relatively high recognition of Google Drive (80%) and Trello (70%) as well-established tools in design education. In contrast, tools like Figma and Slack are moderately familiar but not as universally used.

- B.

Usage frequency of Collaborative Design and Communication Tools, as shown in

Table 26.

The usage frequency data indicate that Google Drive is used most frequently (60% daily), followed by Trello (50%). However, tools like Miro and Figma are used less frequently.

- C.

Educational Impact of Collaborative Design and Communication Tools, as shown in

Table 27.

The educational impact data show a positive effect across all tools, with Google Drive and Trello leading in strong agreement for enhancing teaching and learning.

- D.

Challenges in Using Collaborative Design and Communication Tools, as shown in

Table 28.

The most common challenge faced across all tools is a lack of training, followed by high software costs. The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Seventh Category, Collaborative Design and Communication Tools, as shown in

Figure 8.

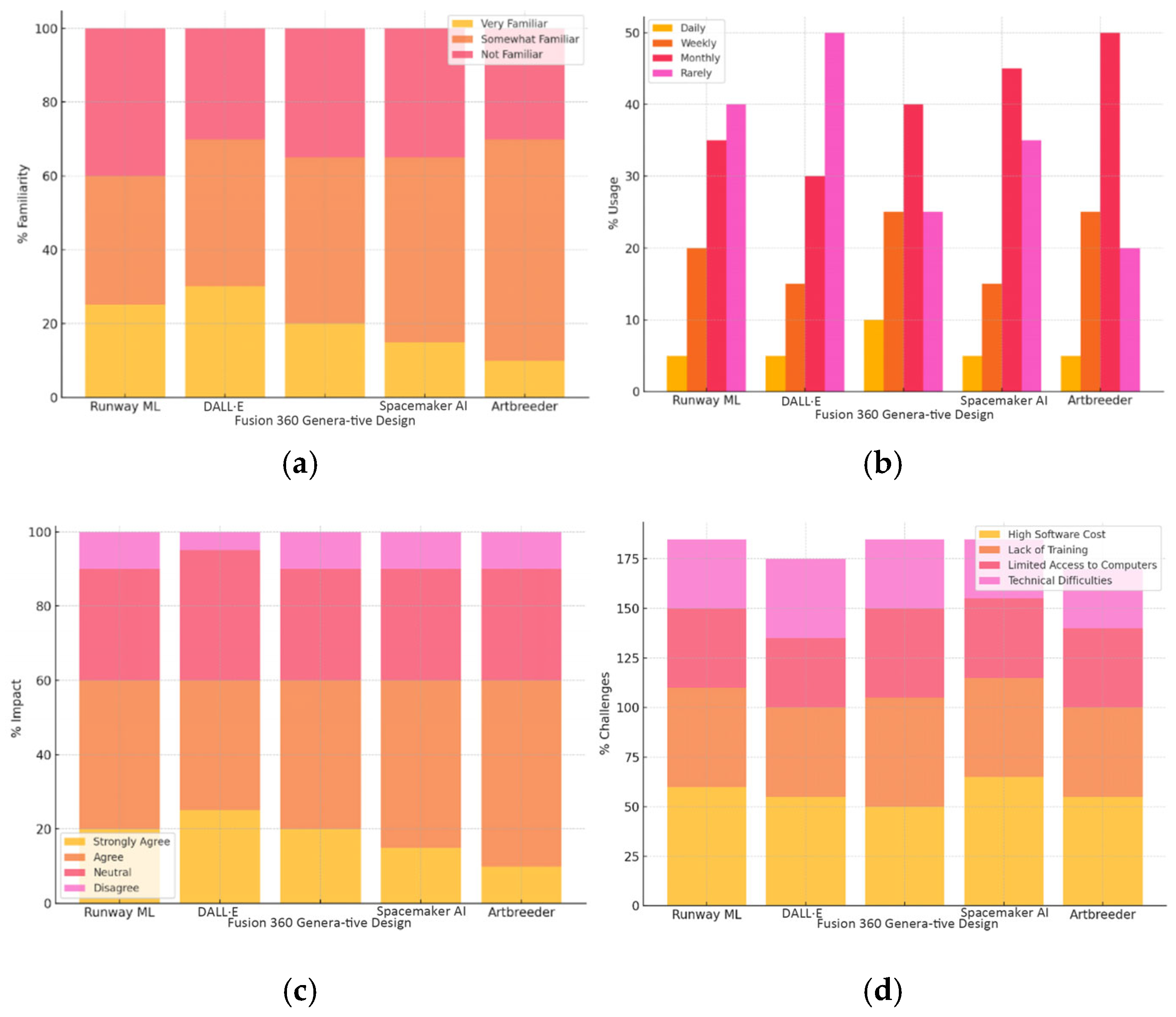

4.1.8. Results Section for the Eighth Category: AI Tools for Design Generation, Editing, and Automation Tools

- A.

Familiarity with AI Tools for Design Generation, Editing, and Automation, as shown in

Table 29.

Results from this analysis show that DALL·E has the highest familiarity, with 30% of respondents being very familiar with it. As an AI tool focused on generating images from text descriptions, it has made a significant impact in creative fields. Runway ML follows closely with 25% familiarity, indicating its growing presence in design education for AI-driven design generation. Fusion 360 Generative Design has 20% familiarity, which reflects its more specialized application in engineering and architecture design. Spacemaker AI and Artbreeder have lower familiarity rates, with 15% and 10%, respectively, indicating that these tools are still relatively niche in the design education sector.

- B.

Usage Frequency of AI Tools for Design Generation, Editing, and Automation, as shown in

Table 30.

Results from this analysis show that Fusion 360 Generative Design has the highest daily usage at 10%, suggesting it is utilized in more specialized courses focusing on generative design and parametric modeling. Runway ML and DALL·E are used more on a monthly or rarely basis, with 35% and 30% of respondents using them monthly, indicating that while these tools are seen as valuable, they may not yet be integrated into day-to-day curricula. Spacemaker AI and Artbreeder show lower daily usage, with only 5% using them regularly, but both tools are utilized in more advanced or experimental contexts.

- C.

Educational Impact of AI Tools for Design Generation, Editing, and Automation, as shown in

Table 31.

Results from this analysis show that DALL·E has the strongest perceived educational impact, with 25% of educators strongly agreeing that it enhances teaching and learning, particularly in creative and conceptual design contexts. Runway ML also shows a positive impact, with 20% of respondents strongly agreeing that it improves education. As an AI platform for creative applications, it has a unique role in generating design ideas. Fusion 360 Generative Design and Spacemaker AI show a moderate impact, with 20% of educators strongly agreeing on their educational value. These tools are highly specialized and used for specific applications in generative and architectural design. Artbreeder has the lowest educational impact but still shows some potential, with 10% of educators strongly agreeing about its usefulness in design education.

- D.

Challenges in Using AI Tools for Design Generation, Editing, and Automation, as shown in

Table 32.

Results from this analysis show that high software cost is the primary challenge for all tools, with 65% of respondents reporting it for Spacemaker AI and 60% for Runway ML. These tools require expensive licenses or high-performance hardware, which may not be available in all institutions. Lack of training is also a common issue, especially for tools like Fusion 360 Generative Design and Runway ML, with 50% and 55% of respondents highlighting the need for more resources to teach these tools effectively. Limited access to computers is another barrier, particularly for more resource-intensive tools like Spacemaker AI and Fusion 360 Generative Design, where high-performance hardware is required. Technical difficulties are a moderate concern, with 35% of respondents reporting challenges in using these tools effectively.

The following are the charts corresponding to the descriptive analysis for the Results Section for the Eighth Category, AI Tools for Design Generation, Editing, and Automation Tools, as shown in

Figure 9.