Digital Literacy in Higher Education: Examining University Students’ Competence in Online Information Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

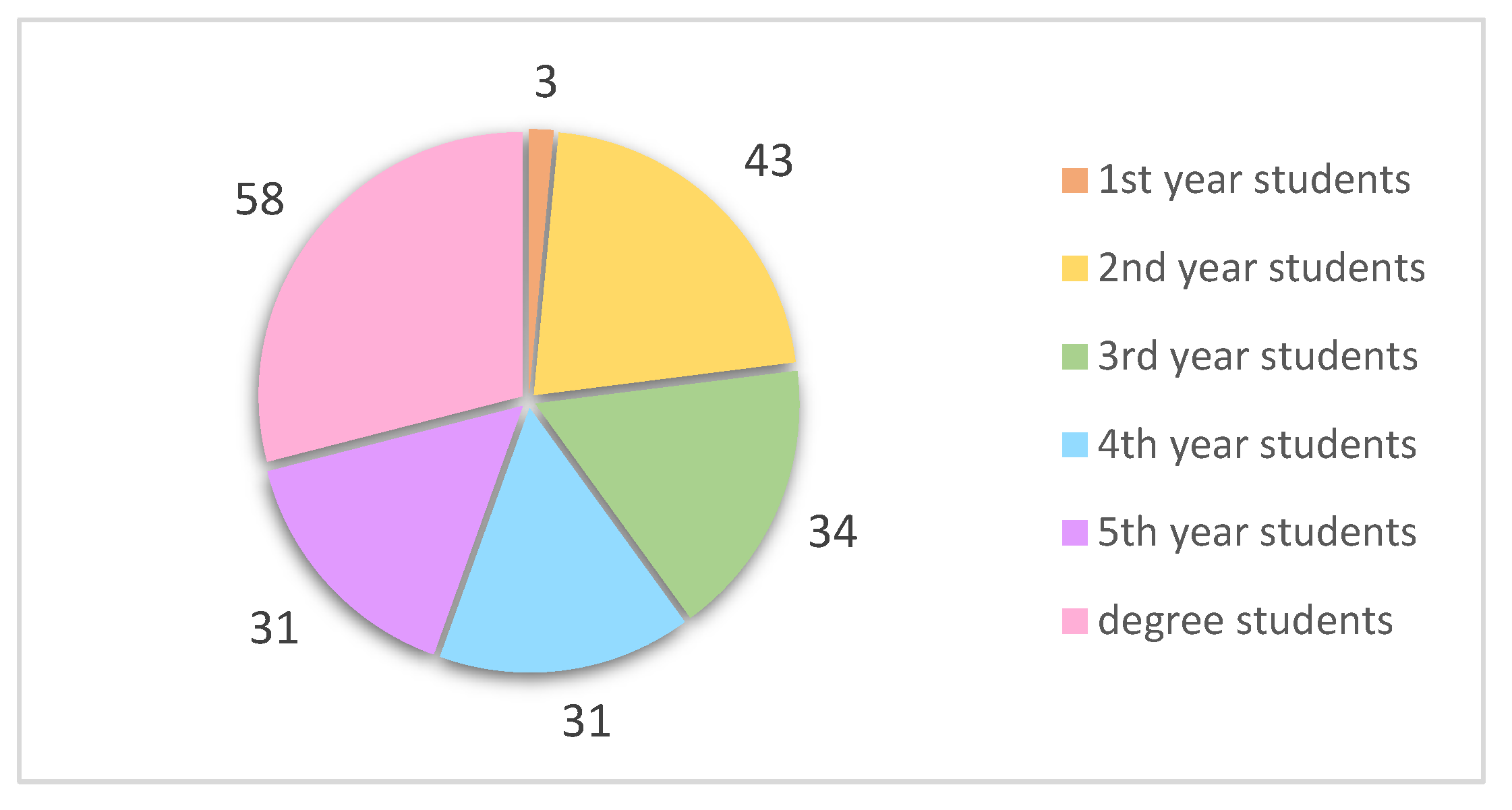

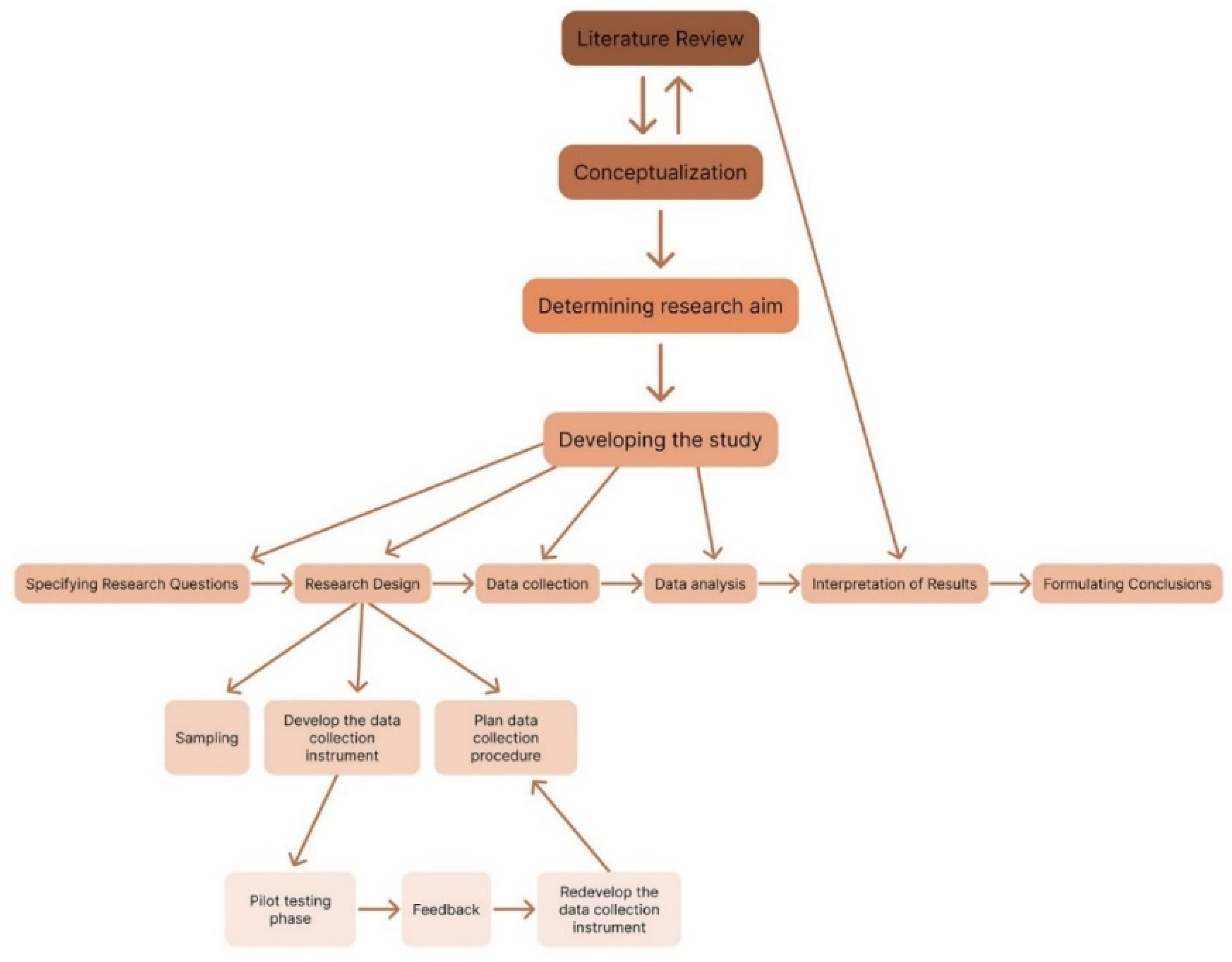

3. Methodology

- RQ1: How do university students in Greece assess their competences in:

- Consuming online content?

- Producing online content?

- Navigating safely in digital environments?

- RQ2a: Which aspects of a multimodal content are mostly recognized for the evaluation of deepfake content?

- RQ2b: What online sources do university students rely on for:

- Daily news?

- Academic/professional purposes?

- RQ2c: What criteria do university students use to select and use appropriate online sources for their information needs?

- RQ2d: What criteria do university students use to assess the validity and reliability of online information?

- RQ3: What is the level of proficiency of university students in using various digital environments?

- RQ4: How effectively can university students communicate in online environments, beyond commonly used platforms?

Instrument Development and Validation

4. Results

4.1. Self-Assessment

- RQ1: How do university students in Greece self-assess their competences in: (a) consuming online content, (b) producing online content, and (c) navigating safely in digital environments?

- Consuming Online Content

- B.

- Producing Online Content

- C.

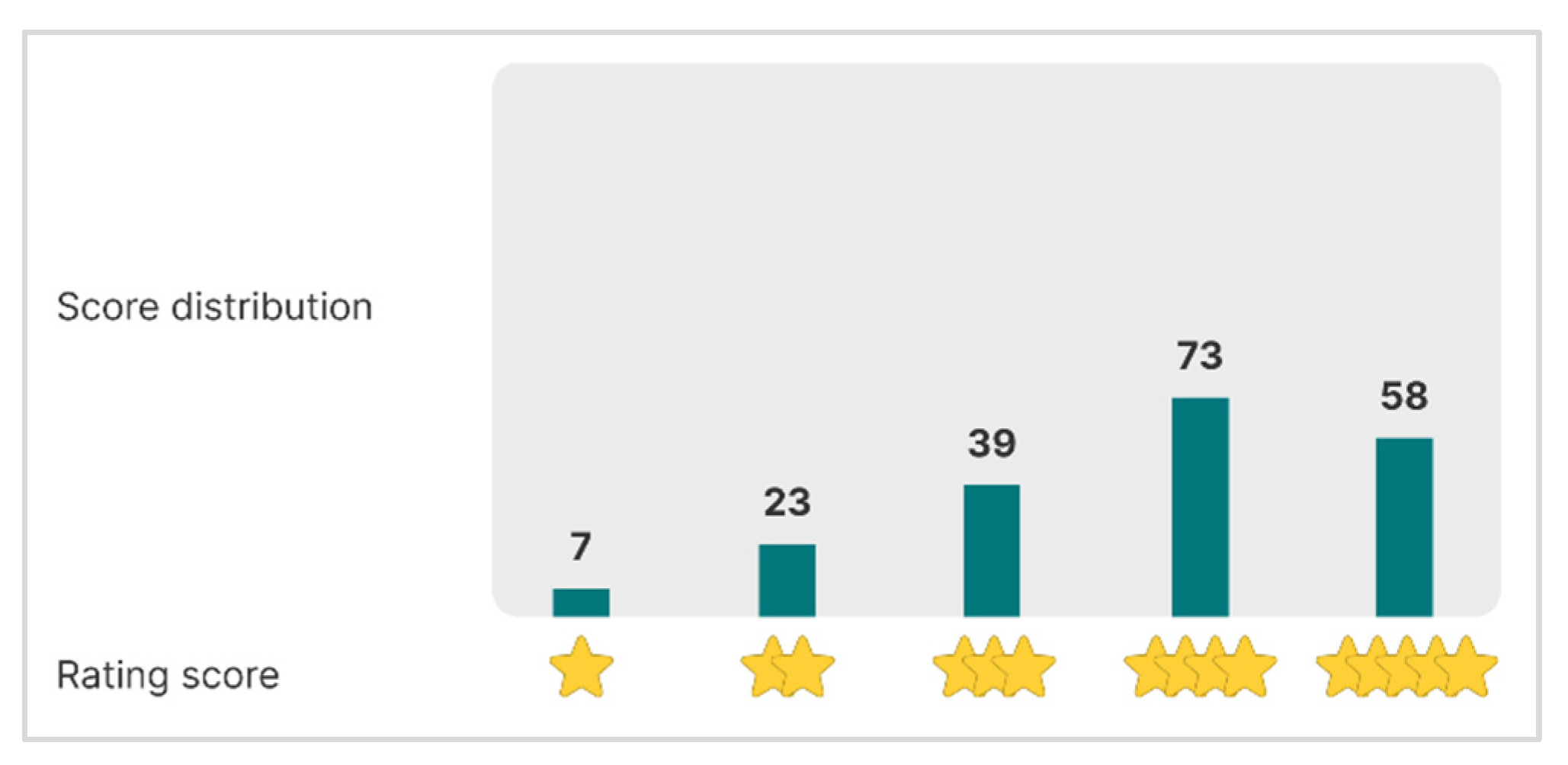

- Navigating Safely in Digital Environments

4.2. Information Evaluation

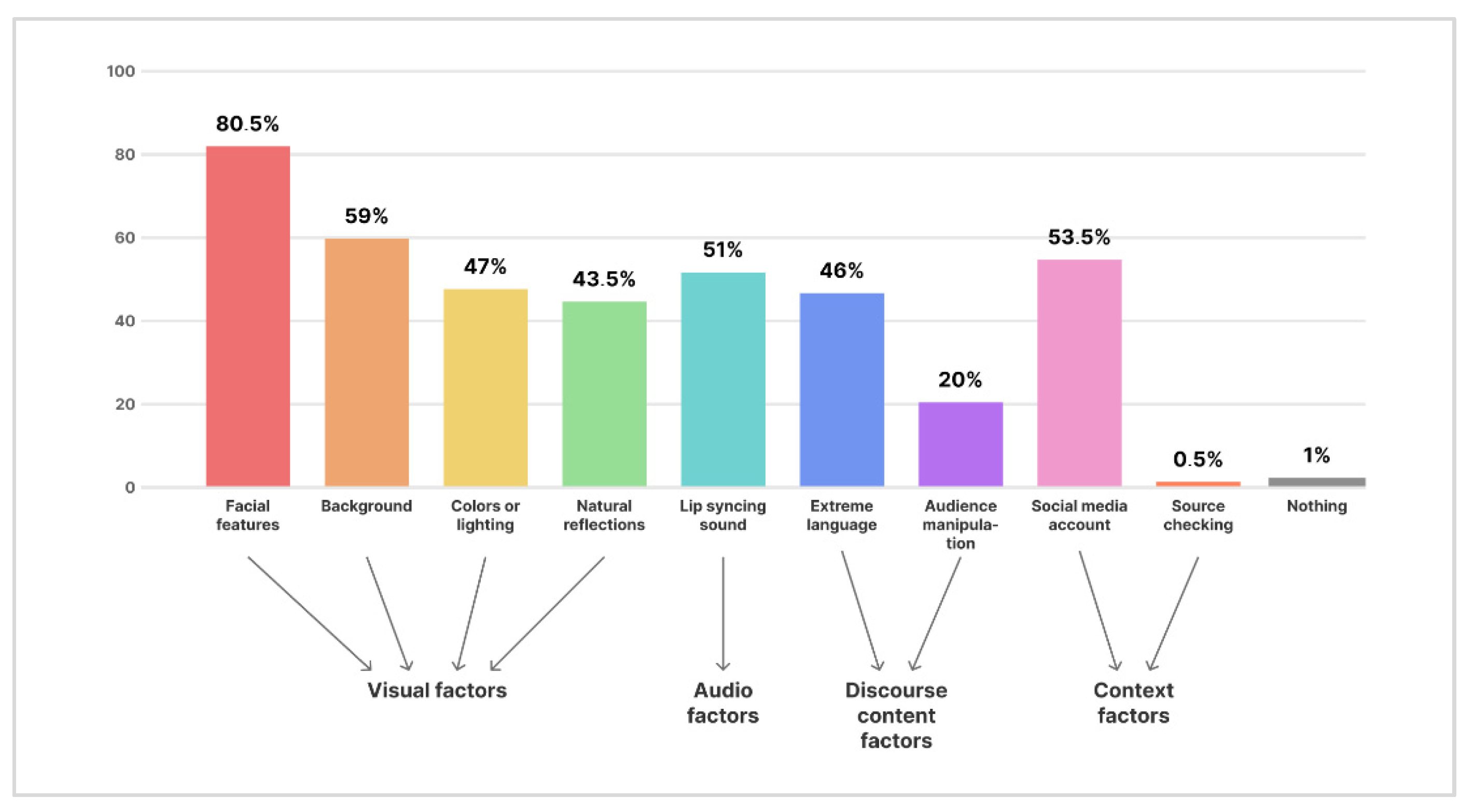

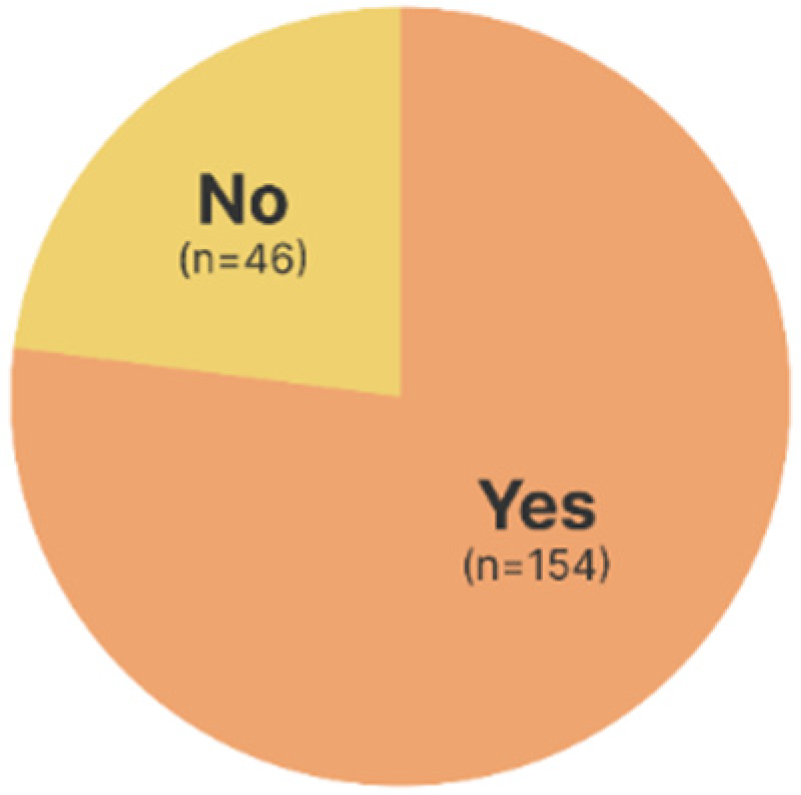

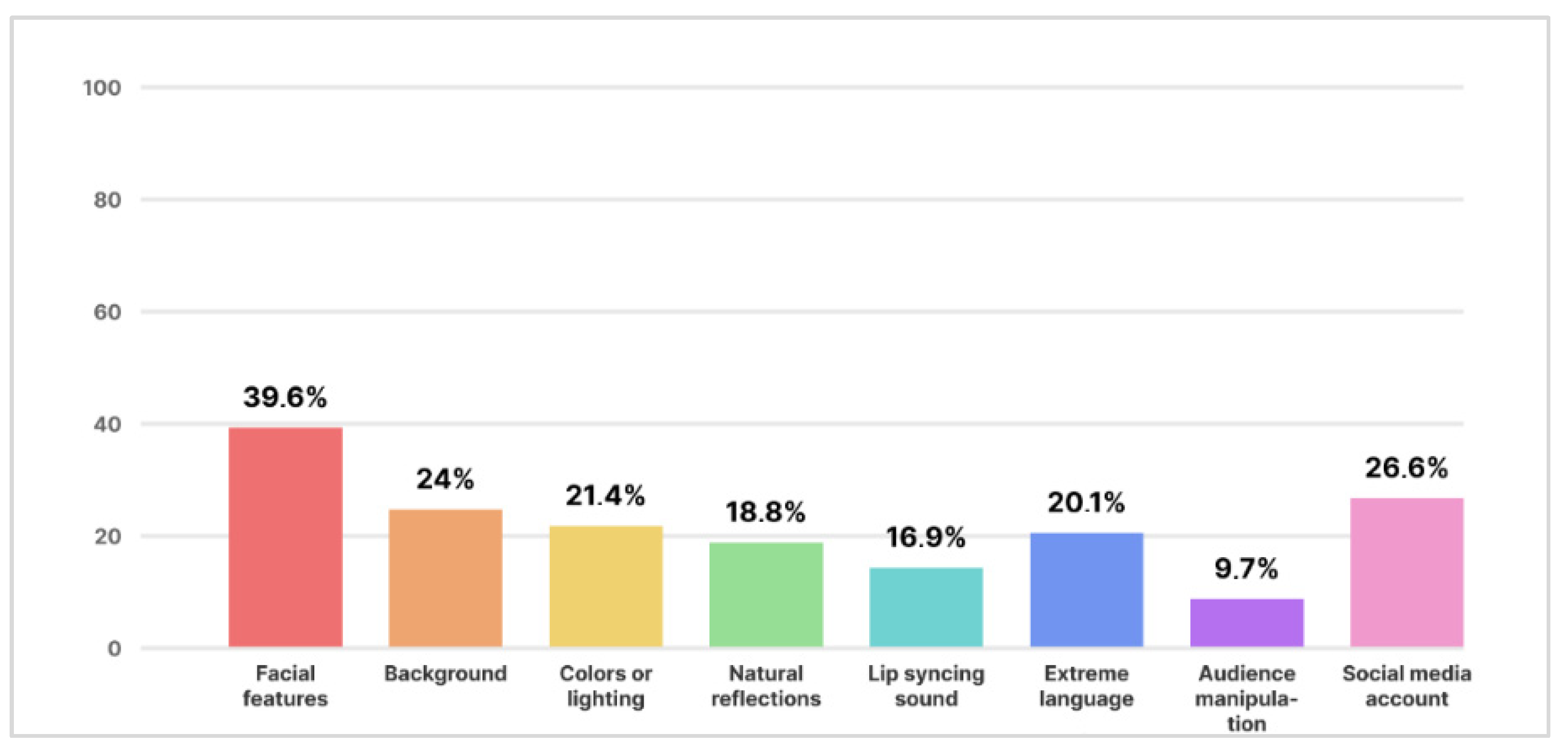

- RQ2a: Which aspects of a multimodal content are mostly recognized for the evaluation of deepfake content?

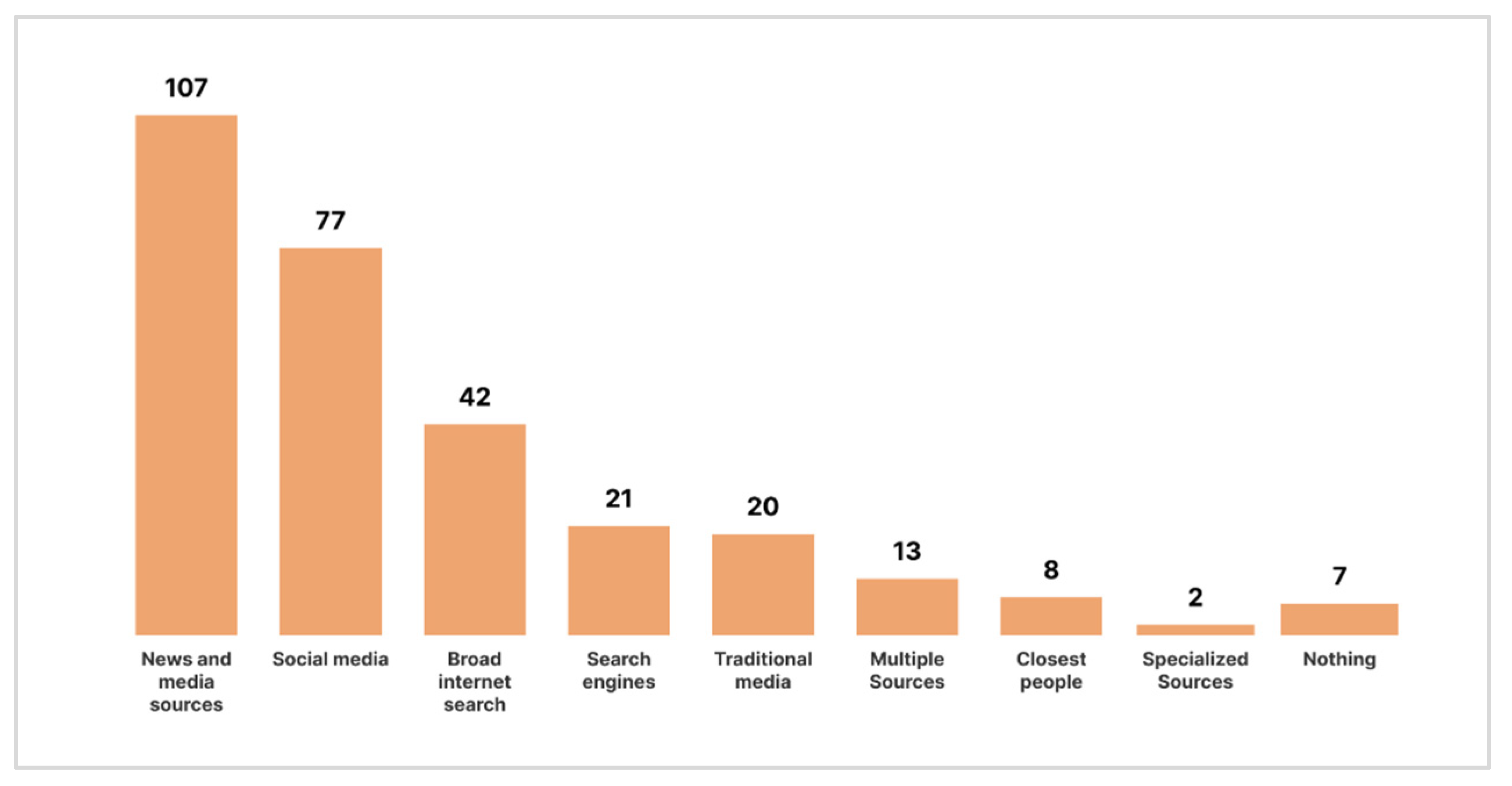

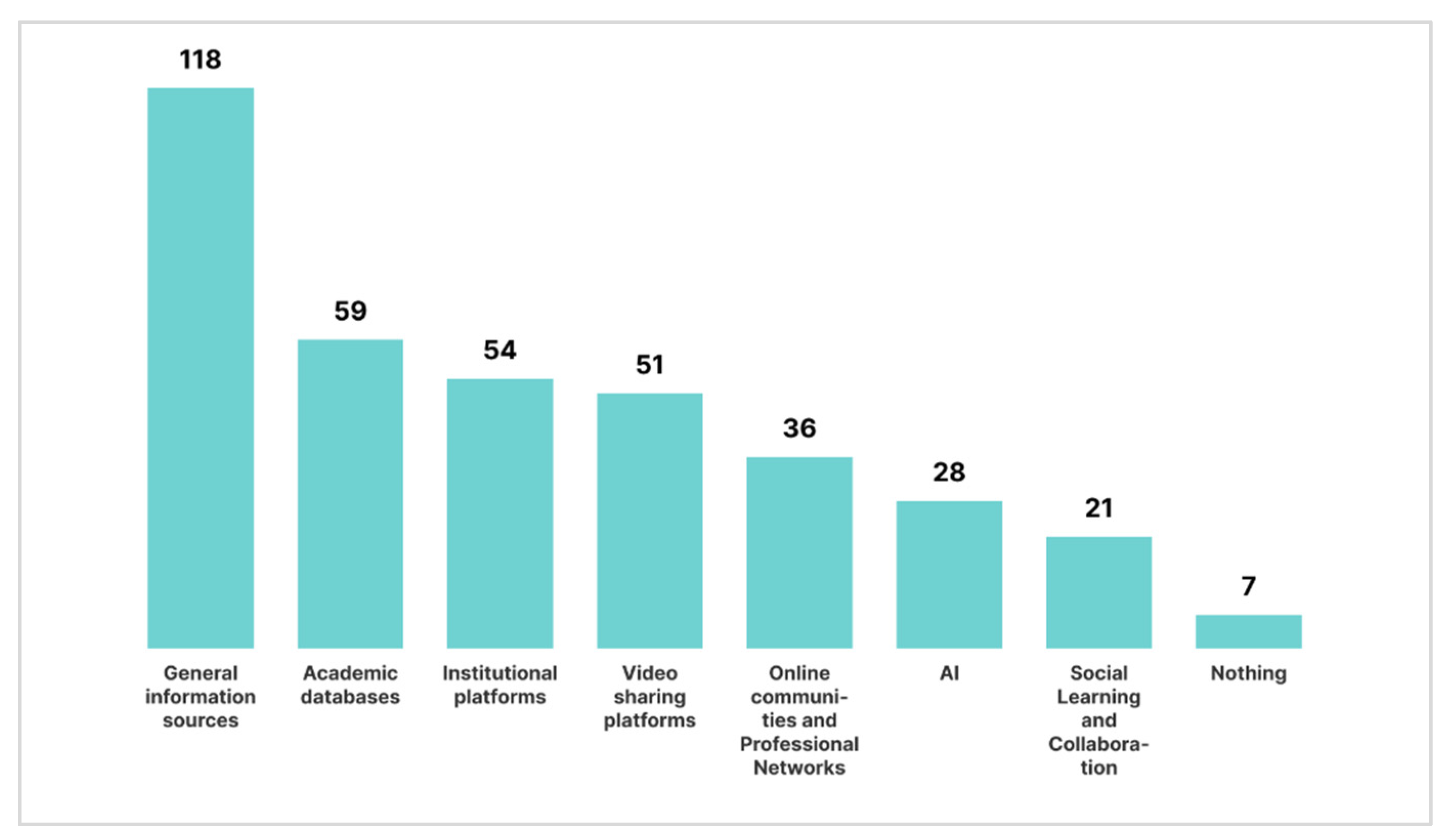

- RQ2b: What online sources do university students rely on for (a) daily news and (b) academic/professional purposes?

- A.

- Daily News

- B.

- Academic/Professional Purposes

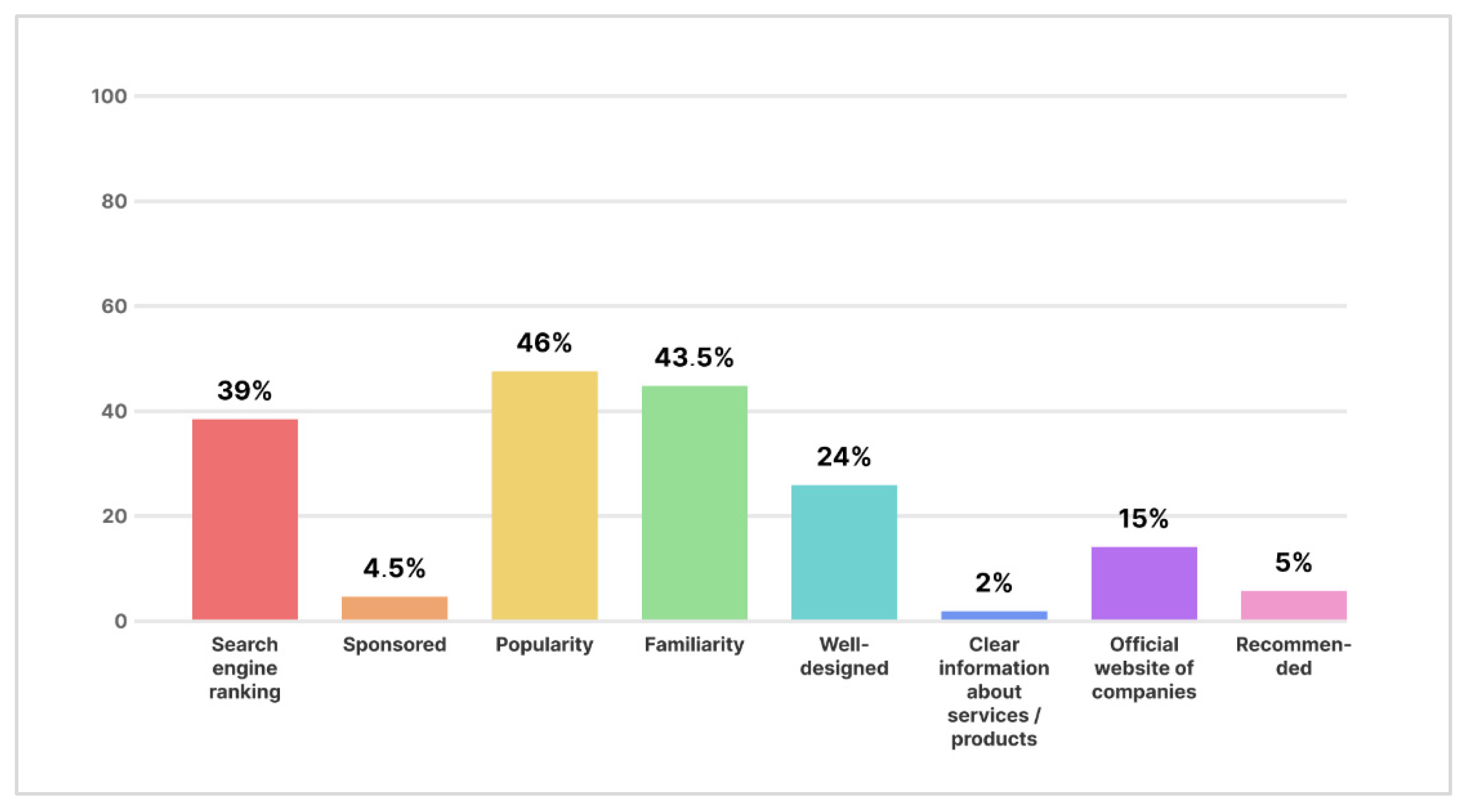

- RQ2c: What criteria do university students use to select and use appropriate online sources for their information needs?

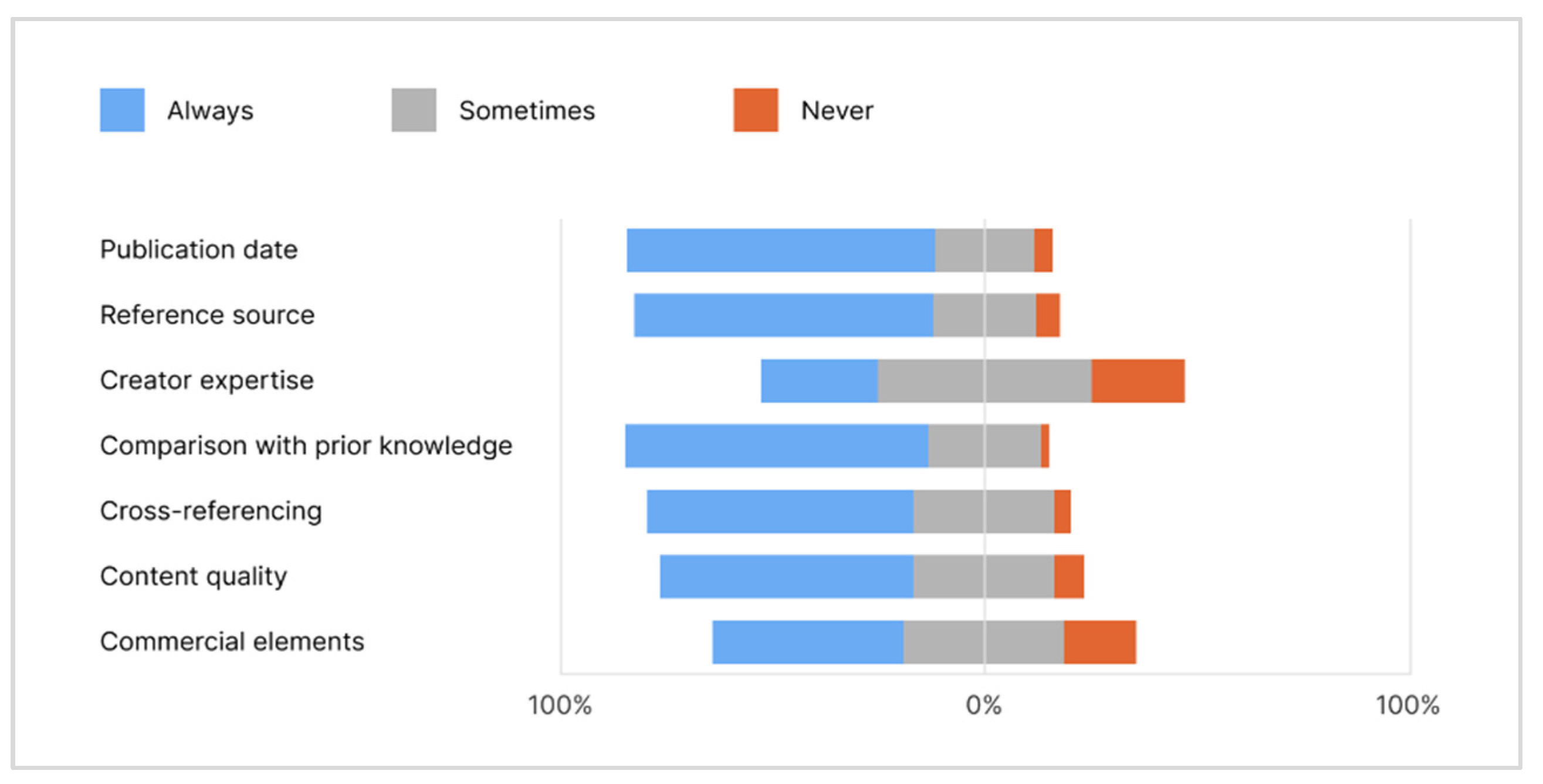

- RQ2d: What criteria do university students use to assess the validity and reliability of online information?

4.3. Technology Utilization

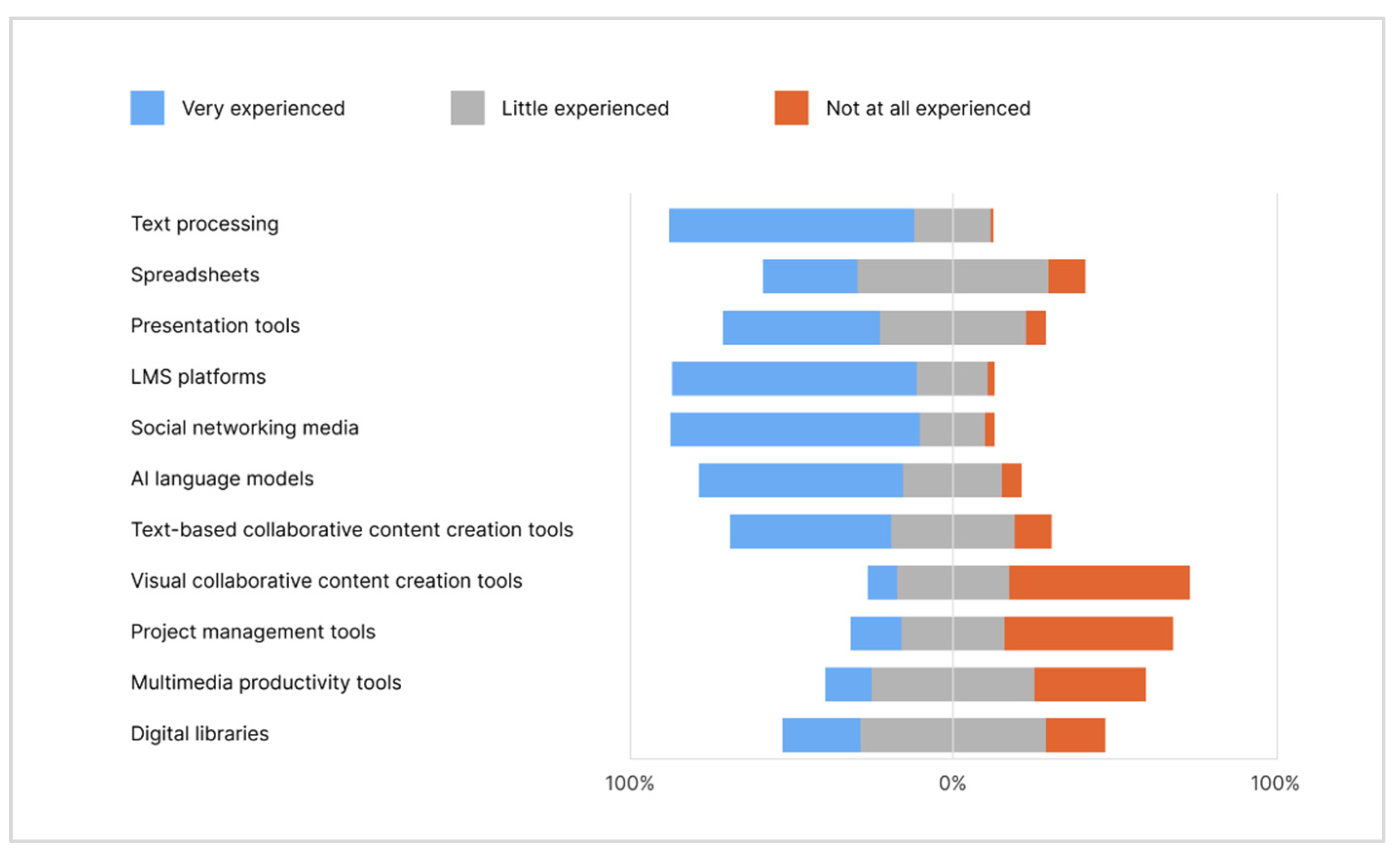

- RQ3: What is the level of proficiency of university students in using various digital environments?

4.4. Participation in Online Communities

- RQ4: How effectively can university students communicate in online environments, beyond commonly used platforms?

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Results & Suggestions

5.1.1. Self-Assessment

5.1.2. Information Evaluation

5.1.3. Technology Utilization

5.1.4. Participation in Online Communities

5.2. Comparing Our Findings with the Existing Literature & Contributions of the Current Study

6. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andriushchenko, K.; Oleksandr, R.; Tepliuk, M.; Semenyshyna, I.; Kartashov, E.; Liezina, A. Digital literacy development trends in the professional environment. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakstone, J.; McGrew, S.; Smith, M.; Ortega, T.; Wineburg, S. Why we need a new approach to teaching digital literacy. Phi Delta Kappan 2018, 99, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisola, A.C.; Doyle, A. Critical information literacy as a path to resist “fake news”: Understanding disinformation as the root problem. Open Inf. Sci. 2019, 3, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Howland, B.; Mobius, M.; Rothschild, D.; Watts, D.J. Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, J. Combating Misinformation and Fake News: The Potential of AI and Media Literacy Education. Available at SSRN 4580385. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375981056_Combating_Misinformation_and_Fake_News_The_Potential_of_AI_and_Media_Literacy_Education (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Kopecky, S. Challenges of Deepfakes. Intelligent Computing. In Proceedings of the Science and Information Conference, London, UK, 26–27 June 2024; Arai, K., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1016, pp. 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorikari, R.; Kluzer, S.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens: With new examples of knowledge, skills and attitudes. In JRC Research Reports JRC128415; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y. Thinking in the digital era: A revised model for digital literacy. Issues Informing Sci. Inf. Technol. 2012, 9, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilster, P. Digital Literacy; Wiley Computer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, D. Defining digital literacy-What do young people need to know about digital media? Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2015, 10, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. European framework for digital literacy. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2006, 1, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviram, A.; Eshet-Alkalai, Y. Towards a theory of digital literacy: Three scenarios for the next steps. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2006, 9, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, E.M.; Erickson, I.; Small, R.V. Digital literacy and informal learning environments: An introduction. Learn. Media Technol. 2013, 38, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbeni, F.; Vosloo, S. Digital Literacy for Children: Exploring Definitions and Frameworks. In Scoping Paper 1; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/1216/file/%20UNICEF-Global-Insight-digital-literacy-scoping-paper-2020.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Thomas, T.; Davis, T.; Kazlauskas, A. Embedding critical thinking in IS curricula. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2007, 6, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, M.S.; Krouska, A.; Troussas, C.; Sgouropoulou, C. Redefining the Concept of Literacy: A DigCompEdu extension for Critical Engagement with AI tools. In Proceedings of the 9th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Athens, Greece, 20–22 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, L.; Cridland, K. If students have ChatGPT, why do they need us? Why educators remain irreplaceable in AI-enhanced learning. In AI-Powered Pedagogy and Curriculum Design: Practical Insights for Educators; Baker, G., Caton, L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawden, D. Origins and concepts of digital literacy. In Digital Literacies: Concepts, Policies and Practices; Lankshear, C., Knobel, M., Eds.; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2008; Volume 30, Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hague, C.; Payton, S. Digital Literacy Across the Curriculum. Curriculum Leadership; Futurelab: Bristol, UK, 2011; Volume 9, Available online: https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/jnhety2n/digital_literacy_across_the_curriculum.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Eshet, Y. Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. J. Educ. Multimed. Hypermedia 2004, 13, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Eshet, Y. Thinking Skills in the Digital Era. In Encyclopedia of Distance Learning; Howard, C., Boettcher, J.V., Justice, L., Schenk, K.D., Rogers, P.L., Berg, G.A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet-Alkalai, Y. Real-time thinking in the digital era. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; Khosrow-Pour, M., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 3219–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. The profound shift of digital literacies. In Digital Literacies: A Research Briefing by the Technology Enhanced Learning Phase of the Teaching and Learning Research Programme (6–8); Gillen, J., Barton, D., Eds.; London Knowledge Lab, Institute of Education, University of London: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ainley, J.; Schulz, W.; Fraillon, J. A Global Measure of Digital and ICT Literacy Skills. UNESCO. 2016. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/ict_literacy/12 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Bawden, D. Information and digital literacies: A review of concepts. J. Doc. 2001, 57, 218–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, K.; Gorman, G.E. Information and digital literacy: A stumbling block to development? A Pakistan perspective. Libr. Manag. 2009, 30, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltay, T. The media and the literacies: Media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media Cult. Soc. 2011, 33, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotherington, H.; Jenson, J. Teaching multimodal and digital literacy in L2 settings: New literacies, new basics, new pedagogies. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 31, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet–Alkalai, Y.; Amichai-Hamburger, Y. Experiments in digital literacy. CyberPsychology Behav. 2004, 7, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibani, A.; Knight, S.; Kitto, K.; Karunanayake, A.; Buckingham Shum, S. Untangling Critical Interaction with AI in Students’ Written Assessment. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet-Alkalai, Y.; Chajut, E. Changes over time in digital literacy. CyberPsychology Behav. 2009, 12, 713–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshet-Alkalai, Y.; Chajut, E. You can teach old dogs new tricks: The factors that affect changes over time in digital literacy. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2010, 9, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana Tabusum, S.Z.; Saleem, A.; Sadik Batcha, M. Digital literacy awareness among Arts and Science college students in Tiruvallur district: A study. Int. J. Manag. Stud. Res. 2014, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mirra, N.; Morrell, E.; Filipiak, D. From digital consumption to digital invention: Toward a new critical theory and practice of multiliteracies. Theory Pract. 2018, 57, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, T.; Milliner, B. Japanese university students’ self-assessment and digital literacy test results. In CALL Communities and Culture–Short Papers from EUROCALL; Research-Publishing.net: Dublin, Ireland, 2016; pp. 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimova, G.A. Digital literacy and digital skills in university study. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagul, I.; Seker, B.M.; Aykut, C. Investigating Students’ Digital Literacy Levels during Online Education Due to COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diepeveen, S.; Pinet, M. User perspectives on digital literacy as a response to misinformation. Dev. Policy Rev. 2022, 40, e12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilian, A. Motivational beliefs, an important contrivance in elevating digital literacy among university students. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Meneses, E.; Sirignano, F.M.; Vázquez-Cano, E.; Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. University students’ digital competence in three areas of the DigCom 2.1 model: A comparative study at three European universities. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 36, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamutoglu, N.B.; Gemikonakli, O.; De Raffaele, C.; Gezgin, D.M. Comparative cross-cultural study in digital literacy. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2020, 88, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göldağ, B. Investigation of the relationship between digital literacy levels and digital data security awareness levels of university students. E-Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 12, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, D.-K.; Groß, N. Artificial intelligence in higher education: Exploring faculty use, self-efficacy, distinct profiles, and professional development needs. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzirides, A.-O.O.; Zapata, G.; Kastania, N.-P.; Saini, A.-K.; Castro, V.; Ismael, S.-A.; You, Y.L.; dos Santos, T.A.; Searsmith, D.; O’Brien, C.; et al. Combining human and artificial intelligence for enhanced AI literacy in higher education. Comput. Educ. Open 2024, 6, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Schofield, L. Developing a conceptual framework for Artificial Intelligence (AI) literacy in higher education. J. Learn. Dev. High. Educ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, A.J.; Van Dijk, J.A. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öncül, G. Defining the need: Digital literacy skills for first-year university students. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2021, 13, 925–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Murray, M.C. Introducing DigLit Score: An Indicator of Digital Literacy Advancement in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the InSITE 2018: Informing Science + IT Education Conferences, La Verne, CA, USA, 23–28 June 2018; 2018; pp. 013–020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martzoukou, K.; Fulton, C.; Kostagiolas, P.; Lavranos, C. A study of higher education students’ self-perceived digital competences for learning and everyday life online participation. J. Doc. 2020, 76, 1413–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, K.M.; Khalid, F.; Browne, A. Information Literacy and Search Strategy Proficiency: A Need Analysis. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2024, 23, 015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huilcapi-Collantes, C.; Martín, A.H.; Hernández-Ramos, J.P. The effect of a blended learning course of visual literacy for in-service teachers. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 131–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydınlar, A.; Mavi, A.; Kütükçü, E.; Kırımlı, E.E.; Alış, D.; Akın, A.; Altıntaş, L. Awareness and level of digital literacy among students receiving health-based education. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein Frei, N.; Wyss, V.; Gnach, A.; Weber, W. “It’s a matter of age”: Four dimensions of youths’ news consumption. Journalism 2024, 25, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetto-Hollywood, N.A.; Elobeid, M.; Elobaid, M.E. Addressing information literacy and the digital divide in higher education. Interdiscip. J. e-Ski. Lifelong Learn. 2018, 14, 077–093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnigor, D. Advancing critical thinking proficiency through optimized pedagogical approaches. Cent. Asian J. Interdiscip. Manag. Stud. 2024, 1, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelhoso, P.; Kalogeras, S. Faculty Perspectives on Web Learning Apps and Mobile Devices on Student Engagement. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2024, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurayev, T.N. The use of mobile learning applications in higher education institutes. Adv. Mob. Learn. Educ. Res. 2023, 3, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, I.; MacKenzie, A. Just Google it! Digital literacy and the epistemology of ignorance. Teach. High. Educ. 2019, 24, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, D.K.; Sheikh, D.K.S. Social media and youth participatory politics: A study of university students. S. Asian Stud. 2020, 28, 353–360. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, İ.; Yaşar, M.E. Measuring social media addiction among university students. Int. J. Contemp. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 468–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, M.S.; Troussas, C.; Sgouropoulou, C.; Voyiatzis, I. Struggling to Adapt: Exploring the Factors that Hamper the Integration of Innovative Digital Tools in Higher Education Courses. In Novel & Intelligent Digital Systems: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference (NiDS 2024), Athens, Greece, 25–27 September 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, M.S.; Troussas, C.; Sgouropoulou, C.; Voyiatzis, I. Technology is not enough: Educators as Catalysts for Sparking Student Interest and Engagement in Higher Education. In Novel & Intelligent Digital Systems: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference (NiDS 2024), Athens, Greece, 25–27 September 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saykılı, A. Higher education in the digital age: The impact of digital connective technologies. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2019, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, J.B.; Aziz, A.A. A Systematic review on soft skills development among university graduates. Educ. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.C.; Pérez, J.; Fluker, J. Digital literacy in the core: The emerging higher education landscape. Issues Informing Sci. Inf. Technol. 2022, 19, 001–013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, C.; Fulton, C. Digital literacy in higher education: A case study of student engagement with e-tutorials using blended learning. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2019, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Parker, L. Reconfiguring Literacies in the Age of Misinformation and Disinformation. J. Lang. Lit. Educ. 2021, 17, n2. [Google Scholar]

- Sriwisathiyakun, K. Utilizing design thinking to create digital self-directed learning environment for enhancing digital literacy in Thai higher education. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2023, 22, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareem, J.; Abhaya, N.B. From Classrooms to Clicks: Exploring Student Attitudes and Challenges in the Shift to Digital Learning in Higher Education. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2025, 24, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabakaran, N.; Patrick, H.A.; Kareem, J. Enhancing English Language Proficiency and Digital Literacy Through Metaverse-Based Learning: A Mixed-Methods Study in Higher Education. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2025, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Angel, N.; Sanchez-Garcia, J.N.; Mercader-Rubio, I.; Garcia-Martin, J.; Brito-Costa, S. Digital literacy in the university setting: A literature review of empirical studies between 2010 and 2021. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 896800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 ✰✰✰✰✰ | 108 | 54.0% |

| 4 ✰✰✰✰ | 73 | 36.5% |

| 3 ✰✰✰ | 17 | 8.5% |

| 2 ✰✰ | 1 | 0.5% |

| 1 ✰ | 1 | 0.5% |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 ✰✰✰✰✰ | 58 | 29.0% |

| 4 ✰✰✰✰ | 75 | 37.5% |

| 3 ✰✰✰ | 48 | 24.5% |

| 2 ✰✰ | 12 | 6.0% |

| 1 ✰ | 6 | 3.0% |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 ✰✰✰✰✰ | 58 | 29.0% |

| 4 ✰✰✰✰ | 73 | 36.5% |

| 3 ✰✰✰ | 39 | 19.5% |

| 2 ✰✰ | 23 | 11.5% |

| 1 ✰ | 7 | 3.5% |

| RQ1a Consuming Online Content | RQ1b Producing Online Content | RQ1c Navigating Safely in Digital Environments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Valid | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean | 4.43 | 3.84 | 3.77 | |

| Std. Error of Mean | 0.050 | 0.069 | 0.075 | |

| Median | 4.50 | 4.00 | 4.00 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.712 | 0.977 | 1.059 | |

| Variance | 0.507 | 0.955 | 1.121 | |

| Range | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Georgopoulou, M.S.; Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Sgouropoulou, C. Digital Literacy in Higher Education: Examining University Students’ Competence in Online Information Practices. Computers 2025, 14, 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120528

Georgopoulou MS, Troussas C, Krouska A, Sgouropoulou C. Digital Literacy in Higher Education: Examining University Students’ Competence in Online Information Practices. Computers. 2025; 14(12):528. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120528

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorgopoulou, Maria Sofia, Christos Troussas, Akrivi Krouska, and Cleo Sgouropoulou. 2025. "Digital Literacy in Higher Education: Examining University Students’ Competence in Online Information Practices" Computers 14, no. 12: 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120528

APA StyleGeorgopoulou, M. S., Troussas, C., Krouska, A., & Sgouropoulou, C. (2025). Digital Literacy in Higher Education: Examining University Students’ Competence in Online Information Practices. Computers, 14(12), 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120528