Quantum Neural Networks in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Advancing Diagnostic Precision Through Emerging Computational Paradigms

Abstract

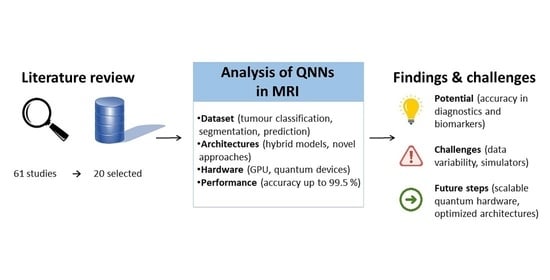

1. Introduction

1.1. Quantum Computers

1.2. Quantum Neural Networks

1.3. Work Selection Criteria

- Dataset: Description of the adopted dataset, including its origin and characteristics (e.g., publicly available MRI datasets or proprietary datasets).

- Simulator: Identification of the simulator or platform on which QNN simulations were run.

- Architecture: Details of the QNN architecture, including layers, quantum gates, or hybrid quantum–classical approaches.

- Hardware: Specification of the hardware employed for running the QNN, including quantum processors or classical computers simulating quantum operations.

- Task: Type of task addressed by the QNN, such as classification, segmentation, or other imaging-related objectives.

- Performance Metrics: Metrics used to evaluate the QNN’s performance, including accuracy, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), precision, recall, or other relevant indicators.

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J. Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Petruccione, F. Supervised Learning with Quantum Computers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J.C.; Barends, R.; Biswas, R.; Boixo, S.; Brandao, F.G.S.L.; Buell, D.A.; et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 2019, 574, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.-S.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y.-H.; Chen, M.-C.; Peng, L.-C.; Luo, Y.-H.; Qin, J.; Wu, D.; Ding, X.; Hu, Y.; et al. Quantum computational advantage using photons. Science 2020, 370, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biamonte, J.; Wittek, P.; Pancotti, N.; Rebentrost, P.; Wiebe, N.; Lloyd, S. Quantum machine learning. Nature 2017, 549, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuld, M.; Bocharov, A.; Svore, K.M.; Wiebe, N. Circuit-centric quantum classifiers. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 032308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezo, M.; Arrasmith, A.; Babbush, R.; Benjamin, S.C.; Endo, S.; Fujii, K.; McClean, J.R.; Mitarai, K.; Yuan, X.; Cincio, L.; et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Fox, N.C.; Jack, C.R.; Scheltens, P.; Thompson, P.M. The clinical use of structural MRI in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Velazquez, E.R.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Parmar, C.; Grossmann, P.; Carvalho, S.; Bussink, J.; Monshouwer, R.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Rietveld, D.; et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Rios-Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.; Carvalho, S.; van Stiphout, R.G.P.M.; Granton, P.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Gillies, R.; Boellard, R.; Dekker, A.; et al. Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, M.; Read, P.; Neven, H.; Boixo, S.; Denchev, V.; Babbush, R.; Fowler, A.; Smelyanskiy, V.; Martinis, J. Commercialize quantum technologies in five years. Nature 2017, 543, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuld, M.; Sinayskiy, I.; Petruccione, F. The quest for a Quantum Neural Network. Quantum Inf. Process. 2014, 13, 2567–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humble, T.S.; McCaskey, A.; Lyakh, D.I.; Gowrishankar, M.; Frisch, A.; Monz, T. Quantum Computers for High-Performance Computing. IEEE Micro 2021, 41, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cohen, E.; Wu, C.; Chen, P.-X.; Davidson, N. Weak-to-strong transition of quantum measurement in a trapped-ion system. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R. Implementing a Hybrid Quantum-Classical Neural Network by Utilizing a Variational Quantum Circuit for Detection of Dementia. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), Bellevue, WA, USA, 17–22 September 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.H.; Adel, E.A.; Mohammed, R.H.; Emaduldeen, A.A.; Jasim, B.L. Application of Quantum Computing in Medical Imaging: Revolutionizing MRI and CT Scan Technology. Am. J. Bot. Bioeng. 2025, 2, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Behrman, E.C.; Steck, J.E. Quantum learning with noise and decoherence: A robust quantum neural network. Quantum Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.; Yun, W.J.; Jung, S.; Kim, J. Quantum Neural Networks: Concepts, Applications, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2021 Twelfth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 17–20 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mitarai, K.; Negoro, M.; Kitagawa, M.; Fujii, K. Quantum circuit learning. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 032309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Lloyd, E.; Sack, S.; Fiorentini, M. Parameterized quantum circuits as machine learning models. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaphika, W.S.; Mahato, R.K.; Makhenjera, M.; Phiri, E.; Olajide, T.E. Quantum Neural Networks for Predictive Modelling in Personalized Medicine: Advancing Treatment Response Analysis and Precision Healthcare. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatunmbi, T.O. Integrating quantum neural networks with machine learning algorithms for optimizing healthcare diagnostics and treatment outcomes. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 1059–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral-García, D.; Cruz-Benito, J.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Systematic literature review: Quantum machine learning and its applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2024, 51, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, I.; Choi, S.; Lukin, M.D. Quantum convolutional neural networks. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Sosa, D.; Telahun, M.; Elmaghraby, A. TensorFlow Quantum: Impacts of Quantum State Preparation on Quantum Machine Learning Performance. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 215246–215255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lim, K.H.; Wood, K.L.; Huang, W.; Guo, C.; Huang, H.-L. Hybrid quantum-classical convolutional neural networks. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2021, 64, 290311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-Y.; Broughton, M.; Mohseni, M.; Babbush, R.; Boixo, S.; Neven, H.; McClean, J.R. Power of data in quantum machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Barakat, M.; Sallam, M. A Preliminary Checklist (METRICS) to Standardize the Design and Reporting of Studies on Generative Artificial Intelligence–Based Models in Health Care Education and Practice: Development Study Involving a Literature Review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2024, 13, e54704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, A. MI-CLAIM Checklist Modelling for Clinical Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Kirtipur, Nepal, 11–13 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijaguna, G.S.; Kumar, D.P.M.; Manjunath, B.N.; Jain, T.J.S.; Lal, N.D. Quantum squirrel search algorithm based support vector machine algorithm for brain tumor classification. Internet Technol. Lett. 2024, 7, e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Che, X.; Fu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, Y. Classification of knee osteoarthritis based on quantum-to-classical transfer learning. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1212373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felefly, T.; Roukoz, C.; Fares, G.; Achkar, S.; Yazbeck, S.; Meyer, P.; Kordahi, M.; Azoury, F.; Nasr, D.N.; Nasr, E.; et al. An explainable MRI-radiomic quantum neural network to differentiate between large brain metastases and high-grade glioma using quantum annealing for feature selection. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Sharifi, A.; Hassantabar, S.; Enayati, S. QAIS-DSNN: Tumor area segmentation of MRI image with optimized quantum matched-filter technique and deep spiking neural network. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6653879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahwar, T.; Zafar, J.; Almogren, A.; Zafar, H.; Rehman, A.U.; Shafiq, M.; Hamam, H. Automated detection of Alzheimer’s via hybrid classical quantum neural networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, D.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Behrman, E.C. Qutrit-Inspired Fully Self-Supervised Shallow Quantum Learning Network for Brain Tumor Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 6331–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.; Anjum, M.A.; Gul, N.; Sharif, M. Detection of brain space-occupying lesions using quantum machine learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 19279–19295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.M.; Aljobouri, H.K.; Al-Waely, N.K.N.; Ibrahim, R.W.; Jalab, H.A.; Meziane, F. Diagnosis of breast cancer based on hybrid features extraction in dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 23199–23212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Khan, M.A.; Masood, A.; Mzoughi, O.; Saidani, O.; Alturki, N. Brain tumor classification from MRI scans: A framework of hybrid deep learning model with Bayesian optimization and quantum theory-based marine predator algorithm. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1335740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendela, K.; Vijayakumar, K.; Gunasekaran, G. QDCNN-DMN: A hybrid deep learning approach for brain tumor classification using MRI images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 101, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.; Anjum, M.A.; Gul, N.; Sharif, M. A secure two-qubit quantum model for segmentation and classification of brain tumor using MRI images based on blockchain. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 17315–17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharabi, N.; Shahwar, T.; Rehman, A.U.; Alharbi, Y. Implementing magnetic resonance imaging brain disorder classification via AlexNet–quantum learning. Mathematics 2023, 11, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, D.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Gandhi, T.K.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Jiang, R. 3-D Quantum-Inspired Self-Supervised Tensor Network for Volumetric Segmentation of Medical Images. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 10312–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.; Naqa, I.E. Evaluation of VQC-LSTM for disability forecasting in multiple sclerosis using sequential multisequence MRI. Quantum Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CJetlin, P.; Sherly, P.A.L. PyQDCNN: Pyramid QDCNNet for multi-level brain tumor classification using MRI image. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 100 Pt A, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, R.; Halder, A. Brain MRI tumour classification using quantum classical convolutional neural net architecture. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 4467–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rudra, B. Quantum-inspired hybrid algorithm for image classification and segmentation: Q-Means++ max-cut method. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2024, 34, e23015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.-J.; Park, S.-E.; Baek, H.-M. Predicting Brain Age and Gender from Brain Volume Data Using Variational Quantum Circuits. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Hur, T.; Park, D.K.; Shin, N.-Y.; Lee, S.-K.; Lee, H.; Han, S. Early-stage detection of cognitive impairment by hybrid quantum-classical algorithm using resting-state functional MRI time-series. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Mao, D.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Li, L. HQNet: A hybrid quantum network for multi-class MRI brain classification via quantum computing. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 261, 125537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID Study | Code Availability | Validation Type | Reproducibility | Hardware Accessibility | Benchmark Dataset | Clinical Relevance | Justification for QNN | Robust Metrics | Methodological Contribution | Total Score | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 15 | [32] |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 14 | [33] |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 15 | [34] |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 12 | [35] |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 | [36] |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 11 | [37] |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 17 | [38] |

| 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | [39] |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 17 | [40] |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | [41] |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 10 | [42] |

| 12 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 | [43] |

| 13 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 18 | [44] |

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 | [45] |

| 15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | [46] |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 11 | [47] |

| 17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | [48] |

| 18 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 15 | [49] |

| 19 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 | [50] |

| 20 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 | [51] |

| ID Study | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Precision (%) | Validation Type/Data Split | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 98.3 | 95.4 | 97.9 | 98.1 | Internal validation (train/test 75/25) | |

| 2 | 95.65 | 97.02 | 97.89 | Internal validation (train/test 90/10) | ||

| 3 | 74 | 77 | 77 | Not reported | ||

| 4 | 98.21 | 5-fold cross-validation (train/test 80/20) | ||||

| 5 | 97 | 85 | 88 | 10-fold-cross-validation (train/test 90/10) | ||

| 6 | 99 | 99 | 72 | Not reported | ||

| 7 | 10-fold-cross-validation (train/test 50/50) | |||||

| 8 * | 84.2 | 85.9 | 82.5 | QCHPs-Pre-contrast | ||

| 88.3 | 87.1 | 89.6 | QCHPs-Post-contrast 1 | |||

| 93.2 | 92.5 | 93.9 | QCHPs-Post-contrast 2 | |||

| 92.7 | 91.8 | 93.5 | Not reported | QCHPs-Post-contrast 3 | ||

| 89.2 | 89.8 | 88.5 | Combined Features-Pre-contrast | |||

| 96.7 | 95.7 | 96.6 | Combined Features-Post-contrast 1 | |||

| 99.5 | 99.3 | 96.7 | Combined Features-post-contrast 2 | |||

| 97.5 | 96.7 | 98.3 | Combined Features-Post-contrast 3 | |||

| 9 | 99.38 | 99.38 | 99.65 | 99.4 | Internal validation (train/test 70/30) | |

| 10 * | 92.3 | 92.8 | 91.8 | BRATS 2018 dataset varying training data | ||

| 93 | 93.5 | 92.9 | 10-fold-cross-validation | Figshare dataset | ||

| 92.7 | 93 | 92.8 | Brain Tumor Classification Database | |||

| 11 | 85 | Internal validation (train/test 80/20) | ||||

| 12 * | 97 | 92 | 93 | Internal validation (train/test 50/50) | Parkinson | |

| 96 | 90 | 91.5 | Azheimer | |||

| 13 * | 98.9 | 96.5 | 73.6 | MRI T1 | ||

| 98.9 | 95.7 | 74 | MRI T1-CE | |||

| 99.1 | 95.7 | 75.1 | FLAIR | |||

| 99 | 96 | 73.6 | Not reported | T2 | ||

| 98.7 | 95.9 | 67.8 | MRI T1 | |||

| 98.7 | 95.8 | 67.8 | MRI T1-CE | |||

| 98.9 | 95.6 | 69.7 | FLAIR | |||

| 98.8 | 95.7 | 69.6 | T2 | |||

| 14 * | 70 | 70 | 70 | MPS-LSTM | ||

| 76 | 76 | 78 | Not reported | MERA-LSTM | ||

| 81 | 75 | 75 | TTN-LSTM | |||

| 15 * | 93.8 | 93.6 | 92.6 | Figshare dataset 1 level | ||

| 93.7 | 93.5 | 92.5 | BRATS 2018 dataset 1 level | |||

| 93.2 | 92.5 | 91.9 | BRATS 2020 dataset 1 level | |||

| 94.1 | 93.3 | 92.6 | Not reported | Figshare dataset 2 level | ||

| 94 | 93.8 | 92.1 | BRATS 2018 dataset 2 level | |||

| 93.5 | 92.6 | 91.7 | BRATS 2020 dataset 2 level | |||

| 16 * | 98.72 | 100 | 97.44 | 97.5 | BRATS 2013 Dataset | |

| 98.46 | 97.62 | 100 | 100 | Internal validation (train/test 70/30–80/20)–90/10) | Harvard Dataset | |

| 98.17 | 97.69 | 98.65 | 98.67 | Private Dataset | ||

| 17 | 98.4 | 97.7 | 99 | Not reported | Classification | |

| 18 | 81.8 | 79.4 | 88.5 | Not reported | Gender prediction | |

| 19 | 58.1 | Not reported | ||||

| 20 * | 97.55 | 97.73 | 99.19 | 97.31 | BT-large-4c | |

| 99 | 99.02 | 99.02 | 98.99 | 5-fold and 10-fold cross-validation | BT-large-2c | |

| 98.86 | 98.57 | 99.43 | 98.65 | Cheng Dataset |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosa, E.; Vaccaro, M.; Placidi, E.; D’Andrea, M.L.; Liporace, F.; Natali, G.L.; Secinaro, A.; Napolitano, A. Quantum Neural Networks in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Advancing Diagnostic Precision Through Emerging Computational Paradigms. Computers 2025, 14, 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120529

Rosa E, Vaccaro M, Placidi E, D’Andrea ML, Liporace F, Natali GL, Secinaro A, Napolitano A. Quantum Neural Networks in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Advancing Diagnostic Precision Through Emerging Computational Paradigms. Computers. 2025; 14(12):529. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120529

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosa, Enrico, Maria Vaccaro, Elisa Placidi, Maria Luisa D’Andrea, Flavia Liporace, Gian Luigi Natali, Aurelio Secinaro, and Antonio Napolitano. 2025. "Quantum Neural Networks in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Advancing Diagnostic Precision Through Emerging Computational Paradigms" Computers 14, no. 12: 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120529

APA StyleRosa, E., Vaccaro, M., Placidi, E., D’Andrea, M. L., Liporace, F., Natali, G. L., Secinaro, A., & Napolitano, A. (2025). Quantum Neural Networks in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Advancing Diagnostic Precision Through Emerging Computational Paradigms. Computers, 14(12), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120529