1. Introduction

Text data analysis is the process of formalizing and analyzing text data that is observed in various domains [

1,

2,

3,

4]. To analyze text data, we build a matrix with documents and keywords through a text mining preprocessing process [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The count data generated from the matrix shows a sparse and imbalanced distribution, where most cells are filled with zeros. This is because keywords that appear only once in a specific document are also included in the column of this matrix. If the given data contains too many zero values, the problem of zero inflation occurs. In other words, zero inflation means that the frequency of zero values is too high for analyzing the data with traditional models such as the Poisson or Negative Binomial models [

9]. The problem of data imbalance due to an inflation of zeros makes data analysis difficult, and if an appropriate method is not used, it can lead to poor prediction performance and interpretation. In data with many zeros, two problems occur. First, since the majority of observations are zeros, the model learning process focuses on zeros and fails to properly reflect the small number of non-zero count data. Second, traditional statistical models such as the Poisson regression model do not properly explain overdispersion or excessive occurrence of zeros, which is the variance of residuals greater than the average [

10,

11].

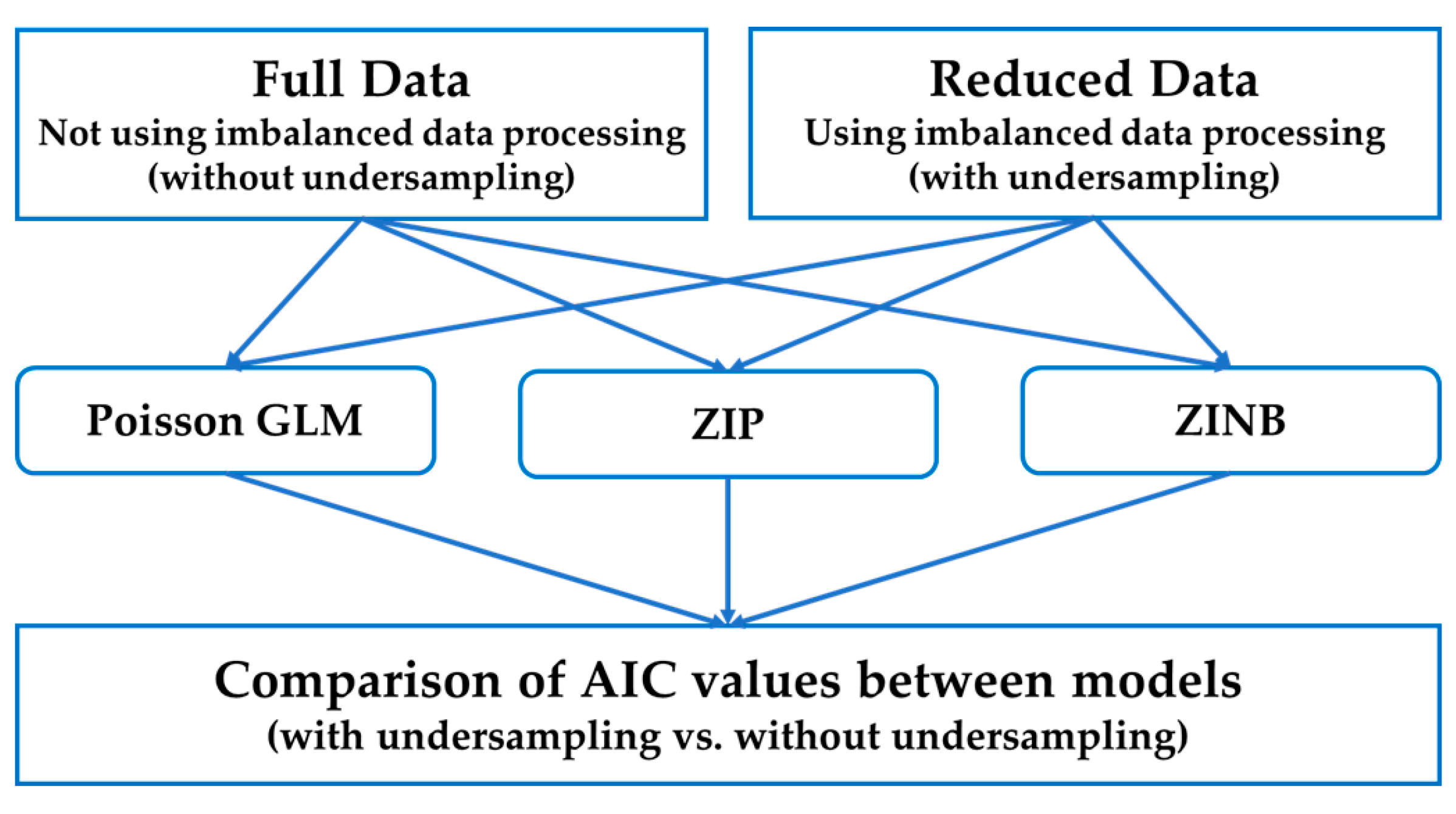

To solve this high-dimensional sparsity problem that occurs in the process of text data analysis, we propose a zero-inflated text analysis method that combines undersampling-based imbalanced data analysis and probability modeling. Using undersampling, we balance zeros and non-zeros and apply three probability models. The models are the Poisson generalized linear model (GLM), zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP), and zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models. In this paper, we compare the performance of probabilistic models by applying them to the original data without undersampling, and to reduced data with undersampling.

Our objective is to improve the fit and interpretability of classical count models under severe zero inflation with a minimal, model-agnostic pre-processing step. While text embedding effectively reduces dimensionality and sparsity, they typically abstract away the count likelihood and may blur the distinction between structural and sampling zeros. We therefore focus on undersampling, followed by Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB, preserving term-level interpretability and enabling likelihood-based criteria such as Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). We later discuss how embedding can be composed with our pipeline when prediction takes priority over interpretability. The text document–keyword matrix is highly sparse, with zero inflation, which undermines the fit and interpretability of the classical count models, due to excess zeros and overdispersion. We therefore pose the following testable hypotheses. Hypothesis: For zero-inflated text counts, undersampling the majority zero class prior to modeling improves the model fit (AIC) for Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. Our study evaluates this hypothesis on a real patent corpus (n = 2929) and a simulated dataset. For clarity, a schematic overview of the full analytical framework is presented in a figure at the end of

Section 3, following the step-by-step methodological development.

This study contributes a simple but effective framework for improving the analysis of zero-inflated text data using undersampling prior to statistical modeling. We do not propose a new model but rather introduce a preprocessing strategy that can be applied to any count-based modeling context: specifically, Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. We assume that the document–keyword matrix exhibits high sparsity and zero inflation, and that the majority of structural zeros can be safely reduced without loss of semantic content. Our experiments focus on improving the model fit, as measured by the AIC, rather than on classification performance. Limitations include the fact that we do not explore oversampling or embedding-based alternatives, and that our method assumes that low-frequency terms including named entities are analytically meaningful and should be retained. Despite these constraints, our results demonstrate that lightweight undersampling leads to consistently improved model fit across both real and simulated corpora.

Next, in

Section 2, we review related work on zero-inflated count modeling, imbalance handling for counts, and text-mining pipelines.

Section 3 presents our methodological framework. To verify the performance and validity of our study, we carry out experiments using real and simulation data in

Section 4. Lastly, we conclude our research in

Section 5.

2. Related Research

2.1. Zero-Inflated Count Data Analysis

Zero-inflated data refers to the data in which the frequency of zero is much higher than a typical probability distribution can explain [

12]. Since zero-inflated data is a count data, we can first consider the Poisson GML. This is the model using the Poisson distribution for analyzing count data [

13]. This model assumes the Poisson probability distribution for the response variable and uses the log link function [

14]. The Poisson GLM is defined as follows [

15,

16,

17].

In Equation (1),

is the parameter of Poisson distribution of the response variable Y. Also,

are explanatory variables and

are the regression coefficients of Poisson GLM. An important assumption in this model is that the mean and variance of Y are equal. Therefore, in real data, the difference between the two values should not be large. However, if there are too many zero values in the given data, it becomes difficult to satisfy this assumption. That is, the Poisson GLM has a simple structure and is easy to interpret but has a constraint that the mean and variance must be equal. Because of this condition, the Poisson GLM has limitations to analyze the zero-inflated count data with overdispersion [

13]. Next, we consider the count data analysis model to solve the zero-inflated problem. To analyze zero-inflated data, various zero-inflated models, such as ZIP and ZINB, have been studied [

18].

The zero-inflated model has a structure that models the probability distribution where Y occurs as a zero value and the probability distribution where Y has a value greater than zero [

13]. In this model, the binomial distribution is mainly used as the probability distribution of Y that produces a zero value, and the Poisson and negative binomial distributions are mainly used as the probability distribution of Y that produces a value greater than zero [

14,

19]. The following equations show the general form of the zero-inflated model [

14].

Equations (2) and (3) represent the occurrence distribution of zero values and the occurrence distribution of values greater than zero, respectively.

represents the distribution of the count data, such as Poisson or negative binomial distributions. In addition, there are zero-truncated, hurdle, and zero-inflated Gaussian models for analyzing zero-inflated data [

19].

2.2. Imbalance Count Data Handling and Text Mining Process

When zeros dominate the outcome, class imbalance can bias estimation and degrade interpretability. Generic strategies such as undersampling, oversampling, ensemble, or boosting adaptations have been studied for regression and count settings, showing that balancing strategies can improve fit or predictive stability when the majority classes overwhelm the signal [

10,

11]. Our work adopts a lightweight undersampling step before model fitting, explicitly to test whether balancing the zero class improves the AIC for Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. In particular, since our research focuses on the problem of text data imbalance, we use procedures for text mining. Constructing a document–term matrix via normalization, tokenization, stopword removal, stemming, and lemmatization is standard practice in text analysis and is supported by mature software stacks (R tm package, Version 0.7-16) [

5]. Such matrices are inherently sparse and often zero-inflated in practical applications, including topic modeling and patent analytics [

7,

20].

Truncated topic models and neural embeddings such as subwords, words, and sentences provide compact document representations that mitigate sparsity and can aid prediction [

18,

20]. While these transformations are effective, they typically decouple inference from the count likelihood and can obscure term-level interpretability, hence our focus on likelihood-based count models; nevertheless, embeddings remain complementary and can be incorporated as low-dimensional covariates. Patent-Text Applications. Prior work has leveraged keyword-based mining and topic modeling for technology forecasting and patent analytics, underscoring the practicality of the pipelines based on the document–term matrix in real corpora [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Our empirical study follows this tradition by analyzing a patent corpus and a matched simulation to evaluate model behavior under controlled zero inflation.

2.3. Prior Work on Zero-Inflated and Text Mining Applications

Numerous studies have explored strategies for modeling zero-inflated count data and handling sparsity in high-dimensional textual corpora. Diverse models are widely used in areas such as ecology, epidemiology, and healthcare, and have recently gained traction in text mining and natural language processing. In terms of imbalanced data handling, Belhaouari et al. (2024) comprehensively reviewed undersampling and oversampling strategies for both classification and regression problems [

10]. While oversampling techniques like the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) are effective for binary classification, they are less suited for sparse count matrices. This motivates our use of undersampling as a lightweight pre-modeling step that retains the interpretability of non-zero counts.

In the context of sparse and zero-inflated text data, Feinerer and Hornik (2025) developed the tm package in R, which provides standard preprocessing operations such as tokenization, stopword removal, stemming, and lemmatization [

5]. These operations are foundational for building document–keyword matrices that serve as input to count-based models. More recently, Xue and Shao (2024) and Bzhalava et al. (2024) employed keyword-based mining and topic modeling on patent corpora, showing the feasibility of structured text analysis for technology forecasting [

4,

20]. The application of zero-inflated modeling in text contexts has been further extended by Jun (2023, 2024), who analyzed patent keyword data using Bayesian ZIP models and GAN-based synthetic keyword generation [

6,

7]. These studies demonstrate the adaptability of count-based and generative models to high-dimensional text domains. However, they do not explore the effect of rebalancing structural zeros in the input data—a gap that our work aims to fill. Lastly, Young et al. (2022) and Lee et al. (2020) provided recent methodological overviews of computational tools and Bayesian variable selection techniques for zero-inflated models, further highlighting the versatility of the ZIP/ZINB models across diverse domains and justifying their selection in our framework [

12,

25].

3. Proposed Framework for Zero-Inflated Text Analysis

We first quantify class imbalance in the document–keyword matrix and then undersample the majority zero class to the frequency, M, of the largest non-zero class. The reduced matrix is modeled alongside the original, with Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB, and AIC is used for comparison. This preserves model interpretability while directly testing whether a minimal imbalance-handling step improves zero-inflated text analysis.

In this paper, we propose a framework to analyze zero-inflated text data. Compared to existing analysis methods that use the original data as is, which includes the zero-inflated problem, we performed changes to the data itself through undersampling, which is used in imbalanced data analysis. In order to analyze text documents, we need to convert the collected documents into structured data. In this process, data preprocessing based on text mining is performed.

3.1. Text Data Preprocessing

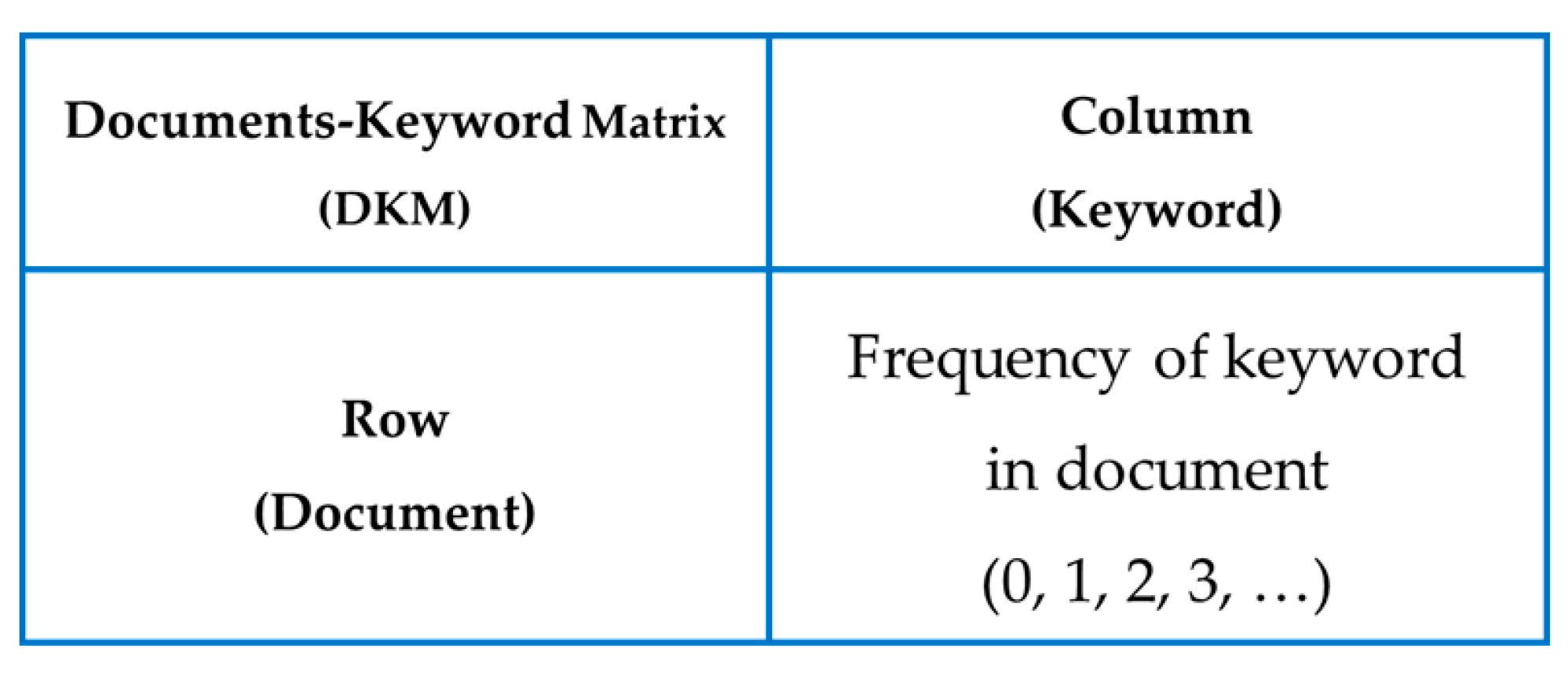

In general, we have to preprocess the text documents by text mining techniques for text data analysis. We construct a document–keyword matrix (DKM) from collected documents by text data preprocessing. The DKM is the result of converting an unstructured text document data into a form that can be statistically analyzed by formalizing it. This matrix is widely used in various natural language processing applications, such as topic modeling and patent analysis [

7,

20]. In this paper, we perform a text mining-based preprocessing procedure to construct this matrix, which expresses each document as a vector and makes each attribute a keyword.

First, we perform text normalization on the collected documents [

5]. The text normalization is the process of converting the collected original documents into a consistent form in order to maintain consistency in text analysis. In this process, all words are converted to lowercase and special characters and numbers are removed. In addition, spaces and punctuation are organized to clearly define the boundaries between words, thereby increasing the accuracy of tokenization. Second, we perform tokenization. Tokenization is the process of separating words, which are the basic units that make up sentences. Typically, space-based tokenization is used, but depending on the language, morphological analysis-based tokenization may also be applied. Third, for stopword removal, we employed the default English stopword list provided in the tm package in R (version 0.7-16), which includes commonly used function words such as ‘the’, ‘is’, ‘and’, ‘in’, and ‘of’ [

5]. This list is designed to remove non-informative tokens that do not contribute to the semantic content of documents. The choice of this list ensures a balance between sparsity reduction and the preservation of informative content. We acknowledge that using a more restrictive stopword list may further alter the degree of zero inflation and impact the balance threshold, M. This aspect will be investigated in future work. Fourth, we perform stemming and lemmatization to integrate different forms of words with the same meaning. The named entity removal (e.g., product names, technical components, and domain-specific proper nouns) was not performed in our preprocessing pipeline. This decision was made to preserve domain-relevant terms that may occur infrequently but carry semantic and technological significance within patent documents. While this may introduce additional sparsity, we consider it to be a trade-off that favors interpretability and completeness of keyword-level analysis. The stemming is a simple rule-based truncation, while the lemmatization is a more sophisticated approach that includes grammatical information and dictionary-based analysis. Finally, based on the preprocessed word list, the document–keyword matrix is constructed by quantifying the frequency information of words appearing in each document. The document–keyword matrix is expressed as an (

) dimensional matrix, based on n documents and p keywords.

Figure 1 shows the DKM constructed from the text documents.

The DKM consists of rows and columns, representing documents and keywords, respectively. Each element in this matrix represents the frequency of a keyword contained in a document. So, this matrix is a count data with (0, 1, 2, 3, …). Since a particular keyword appears only once in all documents, that keyword becomes a column in the DKM, so this matrix can generally suffer from the zero-inflated problem, which means that it contains too many zeros. This problem reduces the performance of the model in text data analysis, so we need to solve this problem in the text data analysis process.

3.2. Imbalanced Data Analysis Processing

To solve the zero-inflated problem in text data analysis, we propose an imbalanced data analysis process to analyze the DKM. In imbalanced data analysis, undersampling is an approach to reduce the data of classes with a large frequency to balance out the data of classes with a small frequency. In our DKM, the majority class is zero value and the minority classes are non-zero values. Undersampling reduces the difference in proportions between classes by removing some of the majority zero data from the imbalanced data. Through this, we reduce the learning bias of the analysis model and increase the explanatory power for the minority non-zero data, ultimately improving the performance of the model. In this paper, the proposed method for the imbalanced data analysis process consists of five steps, as follows.

(Step 1) Checking data imbalance

(1-1) Checking the distribution of zero and non-zero values.

(1-2) Calculating the imbalance ratio.

(Step 2) Determining target of undersampling

(2-1) Determine the reduction ratio of zero data in total.

(2-2) Find the frequency (M) of the largest class among non-zero classes.

(Step 3) Sampling

(3-1) Randomly extract M samples without replacement from data of zero class.

(3-2) Merge M samples of zero with non-zero data.

(Step 4) Modeling

(4-1) Modeling using imbalanced overall data.

(4-2) Modeling using reduced data by undersampling.

(Step 5) Evaluating performance

(5-1) Using AIC as an evaluation index.

(5-2) AIC comparison of models, using data before and after applying undersampling.

In this paper, we determined the number of samples with zeros as the M, representing the frequency value of the largest class among non-zero classes. In other words, to achieve a data balance for analysis, we must match the size of the class with the highest frequency of non-zero values to the size of the samples containing zeros. If we match the sample size to the size of the class with the lowest frequency of non-zero values, the effect of the undersampling will be minimal. Therefore, we used the number M as the threshold for convolving the zero vectors. Though multiple imbalance-handling strategies exist—including oversampling and synthetic data generation—we selected undersampling in this study, due to its simplicity, computational efficiency, and alignment with the goal of reducing the dominance of structurally uninformative zeros. Oversampling in text count matrices may lead to redundancy or overfitting, while undersampling offers a lightweight adjustment that preserves rare but meaningful non-zero patterns.

In our research, using imbalanced data analysis, based on undersampling, we overcome the zero-inflated problem of the DKM in text data analysis. We try to solve the zero-inflated problem by adjusting the ratio of zero and non-zero classes from the initially given zero-inflated data. Using the undersampling procedure described in

Section 3.2, we generate a reduced dataset with balanced zero and non-zero counts. This allows us to directly evaluate how the three models respond to reduced zero inflation.

Although undersampling is a well-known technique in the machine learning literature, its application in the context of classical count-based models for zero-inflated text data has not been widely explored. Our contribution lies in demonstrating that even minimal, model-agnostic undersampling applied to document–keyword matrices, without modifying the modeling structure, can significantly improve model fit in terms of likelihood-based criteria such as AIC.

3.3. Modeling Based on Undersampling for Zero-Inflated Text Data Analysis

In this paper, we consider three representative models for count data analysis, because the DKM is representative count data. The models are Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. In general, the GLM consists of three components as follows: probability distribution of the response variable, the linear predictor, and link function [

13,

26]. According to the data type of the response variable, we can use various probability distributions such as Poisson, binomial, Gaussian, etc. To analyze the text count data, we use Poisson GLM; this model uses Poisson distribution, linear predictor, and log function as a link function. The DKM is represented as the following data.

In Equation (4),

is the target keyword for the response variable.

are the first, second, and pth predictor keywords for the explanatory variables. In Poisson GLM,

follows the Poisson distribution with parameter

. The support of

is

. Also, the expectation and variance of

are equal. So, the Poisson GLM is defined as follows [

13].

In Equation (5),

is the Poisson parameter, representing the expected number of target keywords that occur in documents. We estimate the model parameters

by using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) [

27]. The Poisson GLM does not consider the zero-inflated problem in text data analysis. As explained in

Section 3.1, our DKM data has a zero-inflated problem, so in this paper, we use representative zero-inflated models: ZIP and ZINB. In general, the zero-inflated model is used to analyze the zero-inflated count data [

13,

14,

19].

As introduced in

Section 2.1, the ZIP and ZINB models jointly capture excess zeros and over-dispersed counts through a two-part structure consisting of a binary (zero) component and a count component. In this section, we focus on applying these models to the undersampled text data. The first component is the zero-inflated component, which models the excess zeros in the data. The second is the count component, which accounts for the non-zero counts and follows a count distribution, such as the Poisson or negative binomial distribution. Zero-inflated models are widely used across various disciplines, including epidemiology, ecology, medicine, healthcare, and toxicology, where count data with an overabundance of zeros are frequently observed [

25,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. These models allow for the simultaneous modeling of both the probability of observing a zero count and the distribution of non-zero counts. The following equations provide the formal definition of the zero-inflated model [

14].

In Equations (6) and (7),

is the probability of zero-inflation for the binomial model representing zero occurrence.

is a probability function for the count model of

and

. If

is the Poisson probability function, then the model is ZIP. Also, in ZINB, the function is the negative binomial probability function. The ZIP model is defined as follows [

13,

14,

19].

In Equation (8), the probability of

consists of the binomial of zero and the Poisson of zero. The probability of

is the Poisson of non-zero in Equation (9). Also, in ZINB, the negative binomial distribution is used for

. For the model comparison, we use AIC, which is defined as follows [

26].

In Equation (10),

is the maximum likelihood of the fitted model and

is the number of model parameters. The smaller the AIC value, the better the model performance.

Figure 2 shows our proposed method to analyze the imbalanced text data with a zero-inflated problem.

Full data is the original data, not using imbalanced data processing. That is, we do not perform undersampling on this data. So, this is zero-inflated data that contains too many zero classes. On the other hand, reduced data is the data that has reduced the proportion of the zero class from the full data to the proportion of non-zero classes. We perform undersampling to do this. Next, using the AIC, we compare the performance evaluation results of three models: Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. Using each model, full data and reduced data are analyzed and the AIC values are compared according to whether or not undersampling is used.

4. Experiments and Results

In this paper, we used the R project (

www.r-project.org, Version 4.5.2) for our experiments. We evaluate the proposed pipeline on a patent corpus (n = 2929) and on a simulated zero-inflated dataset that mirrors the document–keyword structure. For each of the four target keywords and three models, we fit both the full and undersampled data and compare the AIC; we analogously evaluate the simulation. To demonstrate the performance and validity of our proposed method, we conducted experiments using data from real domains. We searched patent documents related to synthetic data generating technology from KIPRIS (Korea Intellectual Property Rights Information Service) and USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office) [

21,

22]. A patent is a legal right that gives inventors exclusive rights to developed technology [

23,

24]. A patent document contains various results about the developed technology, such as the title and abstract, inventors, technology code, claims, citation information, and drawings [

24]. For our text analysis, we use the title and abstract of the technology from the patent documents. In another experiment, we generate simulated data, similar to the zero-inflated DKM, and use it for our analysis.

4.1. Patent Documents Related to Synthetic Data Technology

First, we used patent documents that were related to synthetic data technology to verify the performance of our proposed methods. Synthetic data are artificially generated data that mimic real data from a statistical perspective [

35,

36,

37,

38]. The use of synthetic data has become increasingly prevalent in contexts where real data are scarce, sensitive, or difficult to acquire [

36]. The goal of synthetic data technology is to generate data that retain most statistical patterns of the original data while avoiding privacy concerns [

35,

36]. Therefore, in this paper, we collected patent documents on synthetic data generation technology and conducted experiments. The number of collected patent documents was 2929, and we extracted 147 words through the preprocessing process of text mining and finally used 14 keywords among them in the experiment. The 14 keywords are as follows: algorithm, analysis, computing, data, deep, distribution, generating, intelligent, learn, machine, network, neural, statistics, and synthetic. We compared the three models of Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. They were carried out using the text data without and with imbalanced data analysis. We selected the four keywords of synthetic, machine, learn, and generating as target variables for the comparative models.

Table 1 shows the frequency of zero and non-zero values, according to the target keywords.

For example, in the case of the synthetic keyword in

Table 1, out of the total 2929 documents, there were 1161 documents with a value of zero where the keyword did not appear even once, and 679 documents where it appeared once. Next, there were 403 documents where the keyword appeared twice. The remaining non-zero frequencies can be checked in the same way. We can see that the frequency of zero is much larger than the frequency of other non-zero values, not only in synthetic but also in all the other three keywords. To solve the zero-inflated problem of the synthetic keyword data, we performed imbalanced data analysis. We performed undersampling, which makes the frequency of the value 0 equal to the frequency of the value 1. We compare the model fit, measured using AIC, for Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB across both full and undersampled datasets. Results are summarized in

Table 2.

In the case of synthetic, the first keyword in

Table 2, we confirmed that the AIC values were computed to be smaller in all three comparison models when imbalance processing was performed, compared to when imbalance processing was not. That is, we could see that the performance of all count analysis models improved when undersampling was performed. We were able to confirm that the same results as synthetic were obtained for the remaining three keywords of machine, learn, and generating. We also found that the performance of the Poisson GLM was worse than that of the ZIP or ZINB in all cases. This is because the difference between the mean and variance of the frequency values of each keyword is large, as confirmed in

Table 3.

We confirmed that the variance in the frequency values of all keywords was more than twice as large as the mean from the results of

Table 3.

4.2. Simulation Data Analysis

The simulation experiment is included to complement the empirical findings from the patent corpus by providing a controlled setting with known distributional properties. This enables us to verify that the proposed imbalance-handling strategy and model comparisons are robust to different forms of zero-inflated count data and not limited to a specific document collection. Therefore, we performed another experiment by generating simulated experimental data. In this experiment, we generated a count data from the multivariate generalized Poisson distribution [

39,

40,

41,

42]. This is similar to the document–keyword matrix. The generated data consists of one response variable (Y) and four explanatory variables (X

1, X

2, X

3, X

4). The parameters of the Poisson distribution for each of the five variables were set to 1, 3, 4, 4, and 5.

Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients between the five variables.

We conducted the same analysis as the experiment in the previous section, using data based on the correlations in

Table 4. In

Table 5, we see that Y is distributed over values from 0 to 49 with various frequencies.

In particular, we found that the frequency of zero was 3603, accounting for 36% of the total data. The simulation data also had the zero-inflated problem. In other words, we were able to see that the problem with the zero-inflated text data that occurred in the real patent document data in the previous section also appeared in this simulation data. To solve this problem, we carried out the Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB using the simulation datasets with balanced and imbalanced data approaches.

Table 6 shows the results of a performance evaluation between comparative models using simulation data.

In this paper, we performed imbalanced data processing to solve the zero-inflated problem and compared the performance of the model before and after the processing. For this purpose, the imbalanced data processing was performed by undersampling 2208 of the 3603 zero data included in the data, which had a frequency of one. First, we can see that the AIC value after performing imbalanced data processing is smaller than before performing it in the results for the Poisson GLM. We can also find that the same results as those for the Poisson GLM are obtained for ZIP and ZINB. Therefore, we can illustrate the improved performance and validity of the proposed method.

5. Discussion and Implications

This section discusses the main empirical findings of the study, their methodological and practical implications, and the assumptions and limitations underlying the proposed framework. It also outlines future research directions and open questions motivated by both our results and the prior related work.

5.1. Key Findings and Implications

The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether a simple undersampling strategy applied to a zero-inflated DKM can improve the performance of classical count models, namely Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. Across both the real-world patent dataset and the simulated dataset, the empirical results consistently show that applying undersampling to reduce the dominance of zeros leads to improved model fit, as measured by the AIC, compared to the models estimated on the full, unbalanced data. An important observation is that the relative benefit of undersampling is not uniform across models. The Poisson GLM, which is most sensitive to zero inflation and overdispersion, tends to show the largest improvement in AIC after balancing the zero and non-zero counts. ZIP and ZINB also benefit from undersampling, but to a lesser extent, since they already incorporate explicit mechanisms for handling excess zeros and over dispersed counts. This pattern suggests that undersampling can be viewed as a complementary strategy that improves the data environment in which these models operate, rather than as a replacement for specialized zero-inflated models. From a practical standpoint, the findings indicate that a lightweight, preprocessing-based approach can yield tangible benefits without requiring modifications to the modeling framework or additional tuning of hyperparameters. Because undersampling acts only on the input document–keyword matrix, it can be seamlessly integrated into existing analysis pipelines that rely on Poisson GLM, ZIP, or ZINB. This is particularly attractive in settings such as patent analytics, where interpretability at the keyword level is important and practitioners may prefer classical statistical models over more complex black-box approaches. The results from the simulated dataset provide additional support by confirming that the observed improvements are not specific to a single corpus. Even when the degree of zero inflation and the underlying parameter structure are controlled, the same qualitative pattern emerges: undersampling reduces the influence of structurally uninformative zeros, thereby enabling the models to focus more on the informative variation among non-zero counts. Taken together, these findings imply that simple balancing of zero and non-zero entries can be a robust and generalizable preprocessing step for zero-inflated text data analysis.

5.2. Assumptions and Limitations

The usefulness of the proposed framework rests on several assumptions about the data structure and modeling goals. First, we assume that the DKM can be meaningfully represented as a sparse count matrix, where the majority of entries are zeros and a smaller subset consists of non-zero keyword frequencies. This representation aligns with traditional text mining practice but does not capture semantic or contextual information beyond word counts. Second, the undersampling procedure implicitly assumes that a substantial portion of zeros are structurally uninformative in the context of model fitting. In other words, we treat many zeros as arising from a general sparsity phenomenon, rather than from informative absences of specific keywords. This assumption may not hold in all domains; in some applications, the absence of a given term may itself carry an analytical meaning. Third, we use a fixed threshold of M to determine the degree of undersampling of the zero class. This threshold is chosen ex ante and is not optimized or adapted dynamically. Different values of M may lead to different trade-offs between variance reduction and information loss, and our study does not fully explore this design space. Fourth, we focus exclusively on undersampling and do not consider oversampling or synthetic data generation strategies, such as SMOTE-like methods for count data. While these alternatives are widely discussed in the imbalanced learning literature, their direct application to sparse DKM is non-trivial and may introduce other forms of bias or redundancy. Fifth, the models considered in this study are restricted to classical count-based approaches: Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB. We do not compare the models with modern embedding-based or deep learning models, which may offer superior predictive performance at the cost of reduced interpretability. Our evaluation metric is also limited to AIC as an indicator of model fit; other performance criteria such as predictive accuracy, Brier score, or proper scoring rules are not examined. Finally, the empirical analysis is based on a single patent corpus and one simulated data design. Although the results are consistent across these two settings, broader validation on additional domains (for example, social media texts, scientific abstracts, or legal documents) is needed to fully establish generalizability.

5.3. Future Research Directions

The present study suggests several promising avenues for future research, as well as open questions that remain unresolved. One natural direction is to extend the framework to incorporate oversampling or synthetic data generation for non-zero counts. For example, researchers could investigate Poisson or negative binomial-based synthetic augmentation as an analog to SMOTE in the context of sparse count data. An open question is whether such oversampling strategies can achieve similar or better improvements in the model fit without introducing excessive redundancy or overfitting. A second direction involves integrating embedding-based representations with zero-inflated count models. While our analysis is grounded in DKM, recent advances in natural language processing provide contextual word embeddings and sentence representations that may help mitigate sparsity. An open research question is how to combine these dense representations with interpretable count-based models: perhaps through hybrid architectures or hierarchical modeling. A third area for future work is the adaptive selection of the undersampling threshold, M. In this study, M is fixed, based on a simple rule, but one could envision data-driven procedures that choose M to optimize a given criterion (for example, cross-validated AIC or predictive performance). This raises methodological questions about stability, computational cost, and the potential need for regularization when tuning M in high-dimensional settings. Fourth, the literature on zero-inflated models and imbalanced learning suggests that model-based and data-based approaches can be complementary, rather than mutually exclusive. Future research could explore joint frameworks in which undersampling is combined with more flexible model structures, such as Bayesian ZIP/ZINB models, finite mixture models, or hurdle models, to capture heterogeneity in both the zero and non-zero components. Finally, drawing on related research, there are open questions regarding the interpretation of zeros in different text domains and the degree to which structural zeros should be preserved or reduced. For example, in some applications, the absence of a term may signal a distinct topic or class, whereas in others, it may simply reflect general sparsity. Clarifying these semantic and domain-dependent aspects of zero inflation remains an important challenge for future work.

6. Conclusions

When analyzing text data, zero inflation and sparsity in the DKM can severely degrade both the explanatory power and predictive accuracy of count-based models. This is because an excessive number of zeros disproportionately influences parameter estimation and model fit. In this study, we addressed this problem by proposing a simple yet effective framework that combines undersampling of the dominant zero class with classical count models such as Poisson GLM, ZIP, and ZINB, applied to DKM-based count data. The DKM was constructed from text documents through standard text mining preprocessing, with each matrix entry representing the frequency of a keyword in a document, thereby yielding a natural count data structure that is suitable for Poisson- or negative binomial-type models.

Using both a real-world patent corpus and a simulated dataset, we showed that modest undersampling of zeros can consistently improve the model fit, as measured by AIC, without changing the underlying modeling structures or sacrificing interpretability at the keyword level. Rather than introducing new modeling machinery, the contribution of this work lies in demonstrating that a lightweight, model-agnostic preprocessing step, implemented as an imbalanced data analysis via undersampling, can substantially mitigate the adverse effects of excessive zeros in zero-inflated text data. The proposed approach is easy to implement, computationally efficient, and compatible with standard statistical software, making it a practical option for researchers and practitioners working with sparse text data in a wide range of applications.

Although the empirical analysis in this paper focused on a quantum-computing-related patent dataset and a corresponding simulated dataset, the overall process of constructing a DKM and applying the undersampling procedure is generic. Therefore, the proposed framework can be readily extended to other technology domains, as well as to different types of text corpora, such as academic articles, news reports, and online postings, wherever zero-inflated count structures arise. In our previous work, we primarily focused on developing new advanced models for zero-inflated data; in contrast, this paper has shown that carefully adjusting the zero/non-zero ratio in the data can already enhance the performance of existing models.

Despite its simplicity, this study opens several avenues for future research. First, we plan to investigate more advanced model-based extensions of ZIP and ZINB, tailored to zero-inflated text data, including variants for binary and continuous transformations of textual features. Second, we will explore alternative imbalance-handling strategies, such as oversampling or synthetic count generation, and examine how they compare or combine with undersampling in this context. Third, future work will consider additional performance indices beyond AIC, including predictive and calibration-based criteria, and will study adaptive schemes for selecting undersampling thresholds. We hope that this work will encourage further exploration of the interplay between data preprocessing and statistical modeling in the analysis of zero-inflated and imbalanced text data.