Abstract

The global healthcare system faces significant challenges posed by diabetes and its complications, highlighting the need for innovative strategies to improve early diagnosis and treatment. Machine learning models help in the early detection of diseases and recommendations for taking safety measures and treating the disease. A comparative analysis of existing machine learning (ML) models is necessary to identify the most suitable model while uniformly fixing the model parameters. Assessing risk based on biomarker measurement and computing overall risk is important for accurate prediction. Early prediction of complications that may arise, based on the risk of diabetes and biomarkers, using machine learning models, is key to helping patients. In this paper, a comparative model is presented to evaluate ML models based on common model characteristics. Additionally, a risk assessment model and a prediction model are presented to help predict the occurrence of complications. Random Forest (RF) is the best model for predicting the occurrence of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) based on biomarker input. It has also been shown that the prediction of diabetes complications using neural networks is highly accurate, reaching a level of 98%.

Keywords:

machine learning; recommender system; diabetes mellitus; random forest; decision tree; logistic regression; SVM; KNN; diabetic complications; risk prediction; diabetic foot ulcer; diabetic gangrene; cataract; retinopathy; diabetic neuropathy; stroke; cardiomyopathy; nephropathy; diabetic ketoacidosis; body mass index; glucose levels; blood pressure; PIMA dataset 1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, the global burden of diabetes has reached more than 800 million adults, a fourfold increase since 1990. Between 1990 and 2022, the prevalence of diabetes in adults doubled from 7 to 14%, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) experiencing the largest surge. Alarmingly, 59% of adults with diabetes, nearly 450 million people, remain untreated, with 90% living in LMICs, according to the WHO’s South-East Asia and Eastern Mediterranean Regions report [1]. Predicting diabetes (Type 2-NIDD) risk involves identifying individuals with a higher probability of developing diabetes or experiencing related complications. Accurate prediction is critical for early intervention and prevention. Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder that affects millions of people worldwide and can cause serious complications if not properly managed. Early prediction of diabetes plays a critical role in mitigating its impact through timely intervention and treatment. Numerous studies have focused on developing machine learning models to predict diabetes accurately. Research has demonstrated the efficacy of algorithms such as Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, and Random Forests in identifying patterns from clinical and demographic data—see, e.g., Olusanya et al. [2] and Ahmad et al. [3]. The Pima Indian Diabetes Dataset has been widely used in these studies to benchmark predictive performance (Ahmed et al. [4]). Advanced machine learning algorithms have become pivotal in predicting diabetes risk, utilising features such as age, body mass index (BMI), blood glucose levels, and genetic markers (Deberneh et al. [5]). Models such as logistic regression, decision trees, random forests, and support vector machines (SVMs) have shown high precision in predicting diabetes risk based on clinical and demographic data (Chauhan et al. [6] and Wang et al. [7]). Recent studies emphasize the incorporation of ensemble methods, such as gradient boost and XGBoost, to improve predictive performance. These models analyze complex, high-dimensional datasets and identify critical risk factors, including oxidative stress and genetic predisposition. Additionally, novel approaches, such as deep learning and artificial neural networks, have been employed to enhance the accuracy of diabetes prediction using image data and real-time health monitoring systems (Aslan et al. [8]). The Pima Indian Diabetes Dataset, along with other publicly available datasets, has been extensively used as a benchmark to assess model performance (Kakoly et al. [9] and Naz et al. [10]). These studies highlight the potential of machine learning techniques in identifying people at risk of diabetes and guiding preventive measures. Each model differs in methodology and uses different factors to predict the existence of diabetes. The accuracy of models differs significantly. The models’ parameters, the methods used for computing the error function, and the activation functions differ a lot. Many have compared the models used to predict diabetes, such as those by Chatterjee et al. [11], Grundy et al. [12], and Aponte et al. [13], without much concern for the issue of fixing the model parameters. Therefore, the accuracy estimations are not reliable and comparable. Patients suffering from diabetes may suffer from various kinds of complications, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, etc., which must be predicted, enabling corrective actions taken, in advance. Individual biomarker measurements fall in different ranges. A certain kind of risk is associated with every biomarker, depending on the measurement level. The risk associated with each biomarker contributes to the risk of diabetes. Complications are related to the overall risk of diabetes and the individual risk of biomarkers. Assessment of diabetes risk through biomarkers involves identifying and analysing various biological indicators that can predict the likelihood of developing diabetes. Recent research has highlighted the potential of both traditional and novel biomarkers in improving the accuracy of diabetes risk prediction. These biomarkers can provide insight into the underlying pathophysiological processes and inform the development of early intervention strategies. Various types of biomarkers and their roles in assessing diabetes risk have been presented by Ecesoy et al. [14] and Hathaway et al. [15]. Diabetes is often accompanied by severe complications (Reddy et al. [16]), such as nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy, cardiovascular disease, etc. Understanding and predicting the risk levels of these complications is crucial for effective patient care. Various machine learning models, including Decision Trees and Random Forests, have been used to analyze the risk factors that contribute to dealing with these complications. The level of biomarkers has not been considered in this context. Recommendation systems for managing diabetes risk complications are emerging as powerful tools in personalized healthcare. By integrating clinical data, such as HbA1c levels, blood pressure, BMI, and lifestyle factors, with predictive analytics, these systems provide actionable insights for both healthcare providers and patients. Hybrid recommender systems, which combine collaborative filtering and machine learning models, have demonstrated high effectiveness in improving the management of diabetes-related complications, such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular disease (Alian et al. [17]). Recent advances in recommender systems emphasize the use of real-time patient monitoring and adaptive algorithms to deliver customized recommendations to manage risks associated with diabetes complications. For example, systems that leverage artificial neural networks and hybrid collaborative filtering approaches have been developed to predict the progression of complications and suggest appropriate interventions, such as dietary adjustments, medication regimens, and exercise plans (Xie et al. [18] and Arzouk et al. [19]). Most systems suffer from an inaccurate prediction of complications, as the risk levels of the biomarkers used for prediction are not considered.

2. Problem Definition

Several biomarkers, including glucose levels, blood pressure, and body mass index, are used to determine whether a patient has diabetes. Many machine learning models have been used to predict the presence of diabetes in the past. The prediction accuracy varies considerably, making it necessary to conduct a detailed analysis of existing methods to identify the most accurate method for predicting the presence of diabetes. However, these models do not consider the risk associated with the degree of diabetes possessed by a patient.

The risk is associated with the level of measurement of the patient’s biomarkers. Although the risk is associated with each biomarker separately, it is necessary to consider the risk of diabetes, taking into account the risks associated with each biomarker.

Many complications arise based on the risk of biomarkers and the overall risk of diabetes, making it necessary to predict the extent of a specific complication’s existence.

The existence of each complication must be predicted through machine learning models, considering the applicability of the biomarkers to a specific complication. Machine learning models are required to predict complications instantly as doctors continuously monitor the patient’s biomarker levels. Delays in predicting the complication leads to adverse outcomes.

Predicting outcomes through machine learning is more accurate than relying on clinical observations and human diagnosis. The risk assessment is complicated, as it involves multiple dimensions, and it is not possible for humans to accurately assess the overall risk involved.

3. Research Objectives

- Compare various machine learning models based on common model parameters to determine the best approach for detecting the existence of diabetes based on biomarker measurements.

- To find a model that assigns risk for each biomarker based on the clinical measurements and define a method of associating the risk of biomarkers to the overall risk of diabetes.

- Develop several machine learning models that can be used to predict several complications.

4. Utility of This Research

The models presented in this paper will help doctors and hospitals properly diagnose diabetes and treat patients without risk. Currently, around 830 million people worldwide live with diabetes mellitus. This research is expected to be highly beneficial to society. Based on this work, a web-based application can be developed and made freely available to the public, providing meaningful recommendations to diabetic patients for proactive risk management and prevention of diabetic complications.

5. Related Work

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) [20] provides comprehensive guidelines on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, serving as a global standard for clinical and research purposes. The ADA’s diagnostic criteria are based on extensive clinical evidence that correlates blood glucose levels with the risk of diabetes complications.

The American Heart Association [21] categorises blood pressure and explains its relevance in diabetes management. It emphasizes the association between elevated blood pressure and an increased risk of cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients. The AHA’s framework helps both clinicians and patients effectively track and manage blood pressure to improve overall health outcomes.

The American Heart Association [22] also presented the Body Mass Index (BMI) classification system, its connection to obesity-related health risks, and the importance of maintaining a healthy BMI to reduce the risk of diabetes.

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [23] provides global statistics on diabetes, emphasising its socioeconomic impact and advocating for preventive strategies and patient education. The IDF emphasises the urgent need for improved prevention, early diagnosis, and access to effective treatment, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where the disease is rapidly increasing. These figures stress the importance of coordinated global efforts to combat the diabetes epidemic and reduce its health and economic consequences.

Shin et al. [24] focus on enhancing the clinical effectiveness of machine learning (ML) models for diabetes prediction by addressing both model accuracy and practical applicability. Their study evaluates various machine learning (ML) algorithms using clinical datasets to improve predictive performance while ensuring the models’ interpretability for healthcare professionals. Their findings demonstrate that tailored machine learning (ML) approaches not only improve diabetes risk stratification but also facilitate better clinical decision-making.

Syed and Khan [25] present a machine learning-based application designed to predict the risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) within the Saudi Arabian population, using a retrospective cross-sectional study approach. Their research utilized clinical and demographic data to train various machine learning models, aiming to identify individuals at high risk for T2DM early on. They assert that AI-driven tools can support healthcare professionals with timely and accurate diabetes risk assessments.

Al-Sadi and Balachandran [26] developed a comprehensive prediction model for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) focused on prediabetic patients in Oman, employing artificial neural networks (ANNs) alongside six different machine learning classifiers. The authors systematically compared the performance of multiple classifiers, including support vector machines, random forests, and logistic regression, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each model within the Omani population context. Their findings demonstrate that combining ANN with other classifiers can enhance prediction accuracy, supporting personalised and region-specific diabetes management strategies. They did not consider the issue of equivalences among the parameters used for learning the models.

Dutta et al. [27] investigated the early prediction of diabetes by employing an ensemble of machine learning models to improve predictive accuracy and robustness. Their study combines multiple classifiers, including decision trees, support vector machines, and logistic regression, to leverage the complementary strengths of each. The ensemble approach demonstrated superior performance compared to individual models, effectively handling the complexity and variability of diabetes-related data. They ignored the issue of equivalences among the parameters used for modelling.

Qin et al. [28] explored the use of machine learning models for predicting diabetes risk based on individual lifestyle types, highlighting the role of behavioural factors in disease development. Their study integrates lifestyle data, such as diet, physical activity, and smoking habits, with clinical indicators to build predictive models. They demonstrated that machine learning can effectively differentiate diabetes risk levels and improve prediction accuracy.

Yuk et al. [29] presented an artificial intelligence (AI)-based approach for predicting diabetes and prediabetes using routine health checkup data collected in Korea. This study leverages machine learning algorithms to analyse diverse clinical parameters and biomarkers, aiming to identify individuals at risk with high accuracy, while minimising the impact of modal parameters.

Farnoodian et al. [30] focused on the detection and prediction of diabetes through the identification and utilization of effective biomarkers. Their study highlights the integration of advanced computational techniques with biomedical data to improve the accuracy of diabetes diagnosis. By analyzing various biomarkers linked to glucose metabolism, inflammation, and lipid profiles, the authors developed predictive models that improve early detection capabilities. Their approach leverages machine learning algorithms to handle complex biomarker data, demonstrating improved sensitivity and specificity in diabetes prediction. The parameter equivalences, however, are not addressed.

Massaro et al. [31] propose a diabetes prediction system that integrates Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with decision support system (DSS) automation and dataset optimization techniques. The study emphasizes the use of LSTM, a type of recurrent neural network, to capture temporal dependencies in patient health data for more accurate diabetes forecasting. Their automated DSS framework facilitates real-time decision-making by healthcare providers, offering risk assessments and early warning signals for diabetes onset.

Larabi-Marie-Sainte et al. [32] provide a comprehensive review of current techniques used for diabetes prediction. The paper surveys a range of machine learning and statistical methods, including support vector machines, decision trees, neural networks, and ensemble models. The authors analyze the strengths, limitations, and performance metrics of these techniques in predicting diabetes onset. They present how integrating various predictive models can enhance accuracy and reliability in clinical settings.

Madan et al. [33] propose an optimization-based diabetes prediction model that combines Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) networks to enhance prediction accuracy in real-time environments. This study leverages CNN’s ability to extract spatial features and Bi-LSTM’s capability to capture temporal dependencies from health data sequences. The model integrates optimization techniques to fine-tune parameters, improving both efficiency and predictive performance.

Sonia et al. [34] present a machine-learning-based approach for predicting diabetes mellitus risk, utilising a multi-layer neural network combined with a No-Prop algorithm. This study focuses on developing an efficient neural architecture that minimises computational overhead while maintaining high prediction accuracy. The No-Prop algorithm streamlines the training process by minimizing the need for extensive backpropagation, making the model faster and more scalable for real-world applications.

Fitriyani et al. [35] conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis of diabetes risk screening scores across diverse populations, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, US-PIMA Indian, and Trinidadian cohorts. The study evaluates the predictive performance and applicability of various established diabetes risk assessment tools within these ethnic groups. By analyzing the differences in sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy, the authors identify population-specific strengths and limitations of each screening score.

Dritsas and Trigka et al. [36] provide a comprehensive overview of data-driven machine learning methods applied to diabetes risk prediction. The authors examine various algorithms, including decision trees, support vector machines, and ensemble methods, highlighting their effectiveness in early diabetes risk detection based on clinical and demographic data.

Huang et al. [37] explore the early prediction of prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes by integrating genetic risk scores with biomarkers of oxidative stress. Their study emphasizes the combined use of genetic predisposition and physiological stress indicators to enhance the accuracy of diabetes risk assessment. By incorporating these novel biomarkers into predictive models, the authors demonstrate improved sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional risk factors alone. This approach highlights the potential of personalised medicine strategies that utilise both genetic and biochemical data for earlier detection and targeted prevention of diabetes.

Tan et al. [38] developed a predictive model focusing on the incidence of Type 2 diabetes in individuals with abdominal obesity, based on data from the general population, as published in Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy. Their study highlights abdominal obesity as a significant risk factor for diabetes onset, and integrates demographic, clinical, and lifestyle variables to build a robust risk prediction tool. Using statistical and machine learning techniques, the model effectively stratifies individuals based on their likelihood of developing Type 2 diabetes, highlighting the importance of targeted screening and early intervention in high-risk populations.

Toledo-Marín et al. [39] present an advanced approach to predicting blood risk scores in diabetes patients using deep neural networks. Their study leverages deep learning techniques to analyze complex clinical and biochemical data, aiming to improve the accuracy and reliability of diabetes risk stratification. By employing neural network architectures that can capture nonlinear relationships within the data, the authors demonstrate enhanced predictive performance compared to traditional machine learning methods.

Alghamdi et al. [40] investigates the prediction of diabetes complications using computational intelligence techniques. The study focuses on leveraging advanced algorithms, including machine learning and hybrid models, to accurately identify patients at high risk of developing various diabetes-related complications. By analyzing clinical, demographic, and biochemical data, the proposed models demonstrate significant improvements in predictive accuracy and early detection capabilities compared to conventional methods.

Sun et al. [41] developed prediction models specifically targeting the risk of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in Chinese patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus, as detailed in renal failure. Their research employed various statistical and machine learning techniques to identify key clinical and biochemical risk factors associated with the onset and progression of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). The study emphasizes the importance of localized, population-specific models that account for demographic and genetic differences, enhancing prediction accuracy.

Serés-Noriega, Perea, and Amor et al. [42] investigated the screening of subclinical atherosclerosis and its predictive value for cardiovascular events in individuals with Type 1 diabetes, as published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine. The study emphasizes the heightened cardiovascular risk faced by this population and investigates non-invasive imaging and biomarker-based screening tools to detect early vascular changes before clinical symptoms emerge. Their findings suggest that systematic screening for subclinical atherosclerosis can significantly improve the prediction of adverse cardiovascular events, enabling timely clinical interventions. This research underscores the importance of integrating advanced diagnostic methods into diabetes management to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with Type 1 diabetes.

Gosak et al. [43] present a comprehensive literature review on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for predicting diabetic foot risk in patients with diabetes, published in Applied Sciences. The review highlights how AI techniques, including machine learning and deep learning algorithms, have been increasingly applied to analyze clinical, imaging, and sensor data to identify early signs of diabetic foot complications. The study emphasises the potential of AI-based predictive models to improve early detection, personalise risk assessment, and assist healthcare professionals in preventing severe outcomes such as ulcers and amputations. By synthesising findings from multiple studies, Gosak et al. underscore the critical role of AI in enhancing diabetic foot care and the need for further research to optimise model accuracy and clinical implementation.

Mu et al. [44] investigated the prediction of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in patients newly diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Their study focused on identifying clinical and biochemical markers that could effectively forecast the onset of DKD, a serious microvascular complication of diabetes. Utilizing advanced statistical and machine learning models, the authors developed predictive tools aimed at early risk stratification, which is crucial for timely intervention and prevention of kidney function decline.

Xia et al. [45] conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on risk prediction models for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. The study critically evaluated various predictive algorithms and biomarkers associated with cognitive decline in diabetic populations, highlighting the growing concern of neurological complications in diabetes management. By synthesising evidence from multiple studies, the authors identified key clinical, metabolic, and lifestyle factors that contribute to MCI risk and assessed the performance of machine learning and statistical models in early detection. Their findings emphasize the need for accurate, individualized risk assessment tools to prevent or delay cognitive deterioration among patients with Type 2 diabetes.

Wang et al. [46] developed and internally validated a kidney risk prediction model specifically for patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. The study leveraged advanced machine learning algorithms to analyse clinical and biochemical data, aiming to improve the early detection of diabetic kidney disease (DKD).

Chen et al. [47] investigated the risk prediction of diabetes progression by applying big data mining techniques on a comprehensive set of physical examination indicators. The study utilised a range of clinical and biochemical features from large-scale datasets to identify key predictors and patterns associated with the progression of diabetes. By integrating diverse physical examination data with advanced data mining algorithms, Chen’s model achieved high accuracy in forecasting the progression stages of diabetes.

Kong et al. [48] employed Bayesian network analysis to explore the complex relationships among factors influencing Type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and their comorbidities. This probabilistic graphical modelling approach allowed for the identification of direct and indirect causal links between various clinical, demographic, and lifestyle variables. The study provides insights into how these factors interplay to increase the risk of both diseases and their coexistence, enabling better risk stratification and targeted prevention strategies.

Toofanee et al. [49] proposed DFU-Siam, a novel deep learning-based model for classifying diabetic foot ulcers. Their approach utilises Siamese neural networks to effectively distinguish between different ulcer types, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy and facilitating timely clinical intervention. The study demonstrated that DFU-Siam outperforms traditional classification methods by learning subtle differences in ulcer images, which is critical for personalized treatment and reducing complications associated with diabetic foot ulcers.

Sun and Zhang et al. [50] developed a diagnostic model for diabetic retinopathy using electronic health records (EHRs). Their study employed machine learning techniques to analyze clinical data for early detection and severity assessment of diabetic retinopathy.

Islam et al. [51] conducted an in-depth study on advanced techniques for predicting the future progression of Type 2 diabetes, highlighting the importance of early and accurate forecasting in clinical decision-making. They utilised a variety of machine learning algorithms, including ensemble methods, recurrent neural networks, and support vector machines, to analyse longitudinal patient data from electronic health records. The study emphasized the integration of temporal trends and multiple clinical indicators such as blood glucose levels, HbA1c, BMI, and comorbidities to improve prediction accuracy. By leveraging these multifaceted data inputs, their models were capable of forecasting disease progression stages with higher precision compared to traditional static models.

Reshan et al. [52] proposed an innovative ensemble deep learning-based Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) designed to enhance the accuracy of diabetes prediction. This study integrated multiple deep learning architectures, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, within an ensemble framework to leverage the strengths of each model. The system processes complex clinical datasets, including patient demographics, laboratory results, and lifestyle factors, transforming them into actionable insights for early detection of diabetes. By combining predictions from different deep learning models, the ensemble approach enhances robustness and generalization, outperforming individual models in both sensitivity and specificity.

Linkon et al. [53] present an evaluation of feature transformation techniques combined with various machine learning models aimed at the early detection of diabetes mellitus. The study examines the impact of various data preprocessing methods—such as normalisation, scaling, and dimensionality reduction—on the performance of classifiers, including decision trees, support vector machines, and neural networks. The research focuses on enhancing prediction accuracy and model robustness by refining feature representation.

Dorcely et al. [54] investigates emerging biomarkers that play a crucial role in the early detection and monitoring of prediabetes, diabetes, and their related complications. These novel biomarkers include inflammatory markers, adipokines, and metabolic indicators, which reflect underlying pathophysiological changes such as insulin resistance, beta-cell dysfunction, and chronic inflammation. Identifying these biomarkers enables more precise risk assessment and helps tailor personalized interventions to delay or prevent disease progression and complications like cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, and neuropathy. The study emphasizes the importance of integrating biomarker data with clinical parameters to improve diabetes management outcomes.

Fazakis et al. [55] present an extensive study on the application of various machine learning tools for the long-term prediction of Type 2 diabetes risk. The research evaluates multiple algorithms, including decision trees, support vector machines, and ensemble methods, to identify key predictors from clinical and lifestyle data. Their findings highlight the effectiveness of machine learning models in capturing complex patterns and improving prediction accuracy compared to traditional statistical methods.

Guo et al. [56] explore the role of oxidative stress and epigenetic regulation in the pathological changes of lens epithelial cells that contribute to diabetic cataract development. The study details how chronic hyperglycaemia-induced oxidative damage and epigenetic modifications disrupt cellular homeostasis, leading to lens opacity. By elucidating these molecular mechanisms, the research provides insight into potential therapeutic targets for preventing or slowing cataract formation in patients with diabetes.

Alkhodari et al. [57] present a study focused on screening for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) in diabetic patients exhibiting microvascular complications, leveraging machine learning methods. CAN is a serious complication affecting the autonomic regulation of the cardiovascular system in diabetes, often leading to increased morbidity and mortality. The research utilized 24 h heart rate variability (HRV) data, which reflects the autonomic nervous system’s control over the heart, as a key diagnostic biomarker. Various machine learning algorithms were applied to analyse HRV features extracted from continuous ECG monitoring, to classify patients with CAN accurately.

Rahim et al. [58] proposed an integrated machine learning framework designed to improve the prediction accuracy of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Recognizing the complexity and multifactorial nature of CVDs, the study combined multiple machine learning algorithms to leverage the strengths of each and enhance predictive performance. The framework incorporated data preprocessing, feature selection, and model optimization techniques to handle high-dimensional clinical datasets effectively. Various classifiers, such as random forest, support vector machines, and gradient boosting, were evaluated, with the integrated approach demonstrating superior accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity compared to individual models. The study emphasises the importance of a holistic machine learning pipeline for early detection and risk assessment of cardiovascular conditions, which could facilitate timely clinical decision-making and personalised patient care.

Salih et al. [59] present a machine learning approach for diabetes prediction using the PIMA Indian dataset. The study evaluates multiple algorithms, including decision trees, support vector machines, and neural networks, to identify the most effective model for early detection of diabetes. The authors report that ensemble methods and hybrid models achieve superior performance compared to single classifiers. Their findings demonstrate that machine learning can provide reliable and cost-effective tools for diabetes screening and risk assessment, potentially aiding in timely medical interventions.

Dagliati et al. [60] explored the application of machine learning techniques to predict complications in patients with diabetes. Using clinical data, the study evaluated models like decision trees, support vector machines, and logistic regression. These models were trained to identify patterns and risk factors associated with long-term complications, including nephropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular diseases. A key focus was on the temporal nature of the data and its integration into predictive modelling. The study utilized electronic health records (EHRs) to generate dynamic patient profiles over time. The results showed that machine learning can accurately stratify risk and assist in proactive disease management. Interpretability and clinical relevance were emphasized to support real-world decision-making.

Dinh et al. [61] presented a data-driven approach for predicting both diabetes and cardiovascular disease using machine learning techniques. The study utilized a large dataset containing patient health records and lifestyle variables. Various algorithms, including decision trees, random forests, and support vector machines, were applied and compared for performance. The goal was to assess predictive accuracy and identify key risk factors. Feature importance analysis highlighted the relevance of age, BMI, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. The results showed that ensemble models, particularly random forests, performed best in classification tasks.

Tan et al. [62] conducted a systematic review evaluating various machine learning (ML) methods developed for predicting diabetes-related complications. The review analyzed 48 peer-reviewed studies covering complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy, cardiovascular disease, and diabetic foot. Commonly used ML algorithms included logistic regression, decision trees, support vector machines, random forests, and neural networks. Most models focused on Type 2 diabetes populations and utilized structured datasets like electronic health records (EHRs).

Kee et al. [63] present a systematic review focused on predicting cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients using machine learning (ML) models. The review analyzed over 40 studies, primarily targeting Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) populations. Common complications assessed included coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart failure. Frequently used ML methods included logistic regression, random forests, support vector machines, and deep learning architectures. Data sources were largely based on electronic health records and longitudinal clinical datasets. Feature variables often included age, HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, and duration of diabetes.

Li et al. [64] investigated the performance of various machine learning (ML) models in predicting Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) in adults with Type 1 diabetes using electronic health record (EHR) data. The study utilized a cohort of over 5000 adult patients from a national health database. Several machine learning (ML) algorithms were compared, including logistic regression, random forest, support vector machines, and gradient boosting. Key predictors included insulin dosage, HbA1c levels, frequency of hypoglycemia, and previous hospital admissions. The gradient boosting model performed best, achieving high predictive accuracy. Logistic regression also showed strong performance with fewer variables. Feature importance analysis highlighted HbA1c and history of prior DKA as top predictors. The study highlighted the utility of EHR-based prediction models for identifying early risk.

Seerapu et al. [65] explored the integration of machine learning (ML) and computer vision in the diagnosis and management of diabetic cataracts, a common complication of diabetes. The study discusses recent advancements in automated image analysis, particularly using deep learning models applied to fundus and slit-lamp imaging. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were highlighted for their accuracy in detecting early-stage cataract changes in diabetic patients. The authors emphasize the importance of early detection, which can reduce the risk of vision impairment. Several machine learning (ML) models were evaluated for their classification and segmentation capabilities.

6. Research Gap

Many authors have published articles on diabetes, dealing with the following:

- The relation between biomarkers and diabetes using machine learning models.

- The relation between biomarkers and diabetes considering specific risks such as nephropathy, heart stroke, etc.

- Many studies have been presented that compare different machine learning models in terms of accuracy. The dataset is the same, but the models are not based on the same premises as the model parameters, leading to inaccurate predictions and assessments.

Many studies have been presented that assess a specific complication based on biomarker data while ignoring the risk associated with each biomarker and the overall risk associated with diabetes. In this paper, this research gap is addressed through the following:

- Comparative analysis of machine learning models to predict diabetes based on the same model parameters.

- Assessing risk based on each biomarker measurement and computing the overall risk of diabetes considering risk based on biomarker measurement.

- Machine learning models that predict a complication considering the risk assessment from the point of view of each biomarker and the overall risk of diabetes.

7. Methodology

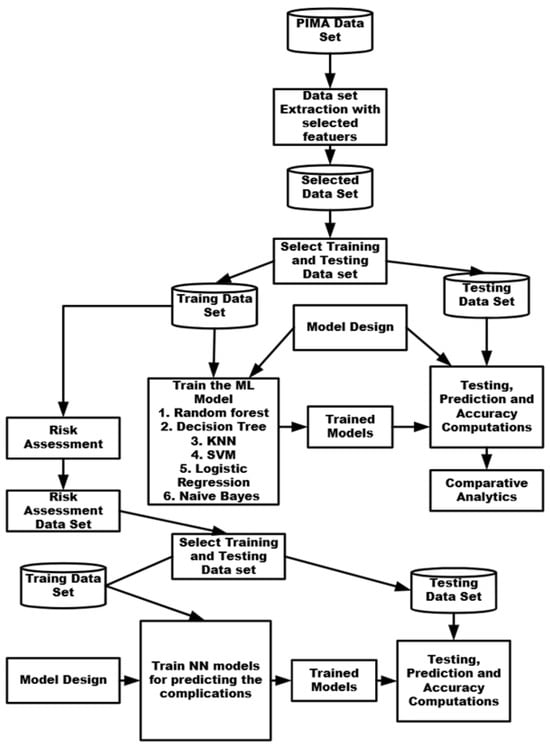

The methodology adopted to predict diabetes and the related complications is shown in Figure 1. First of all, the PIMA dataset was downloaded from the KAGGLE site. The required characteristics, including glucose (GL), blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), and age, were extracted, and a separate dataset was created. A total of 758 records were extracted, of which 90% were used for training and the rest for testing the machine learning models.

Figure 1.

Methodology used for predicting diabetes and its related complications.

The model parameters were fixed, including the learning rate, number of epochs, batch size, activation function, error computations, and optimization function. The issue of overfitting was dealt with by using a regularization function wherever required.

The machine learning models, which included RF (random forest), Decision (DT), K Nearest Neighbors (KNN), SVM (Support Vector Method), LT (logistic regression), and Naive Bayes Classifier were trained using common model parameters and the PIMA training dataset. The models were tested using the PIMA test dataset, and the performance metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score were calculated. RF was found to yield the highest accuracy. A comparative analysis was performed and the best model was found.

Risk analysis was carried out using test data and a new dataset was created to reflect the risk associated with each of the biomarkers, which were combined to obtain the overall risk. This dataset was again split into training data (80% records) and the rest into test data. From the test data, data related to a specific set of biomarkers related to a complication were selected, and a neural network was trained, which was used to predict the possibility of the occurrence of a specific complication. The eight neural networks were thus trained, each reflecting specific complications.

The proposed work comprises two phases. Phase A focuses on predicting the existence of diabetes using different machine learning models and identifying the best-performing model. Phase B involves performing risk analysis based on biomarkers and predicting complications using artificial neural network (ANN) models.

8. Methods and Techniques

8.1. Training Machine Learning Methods for Predicting the Existence of Diabetes

8.1.1. Public Dataset

The PIMA dataset contains 768 records. Table 1 details the features used to compile the dataset. Data analysis was conducted to determine the range of values for each feature individually. Only four features were extracted from this dataset, which included Glucose, Blood Pressure, BMI, and age, for modelling because they are directly related. The feature selection method was not used because the number of features used was limited. A sample of 10 tuples extracted from the PIMA (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/pima-indians-diabetes-database) (accessed on: 19 January 2025) dataset is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample records from the PIMA diabetes dataset.

8.1.2. Equalization of Model Parameters

The model parameters were initially fixed to train the models on the same premises, ensuring that the best model could accurately predict the presence of diabetes within a specific patient based on individual biomarkers.

Adjusting the model parameters for use within each machine learning model is a complex process. The learning models cannot be compared unless the training is carried out using similar parameters. The model parameters were selected based on the equality of the data, the nature of the data (i.e., linearity), the size of the data characteristics, the types of data classification to be performed, and the method used to measure the distance between data points.

The model parameters are to be selected based on the likelihood of the parameters. The commonly used model parameters across all learning models could be based on common characteristics, such as the number of features, linearity of the data, basis for regularization, and type of algorithm (brute force, optimised, linear, uniform). The model parameters should also be selected based on a direct or indirect mapping between the parameters. The mapping of the model parameters among the six learning models is shown in Table 2. Parameters were selected based on equivalences, direct mapping, or indirect relationships. When model parameters are selected based on this criterion, one can ascertain the equivalence among the machine learning models and then select the model that performs best.

Table 2.

Model parameters used for selected machine learning algorithms. Abbreviations are explained in the footnotes.

8.1.3. Machine Learning Models—Trained

Different machine learning models were trained using the PIMA dataset after fixing the model parameters. These models were selected because they deal with binary classification and can apply common characteristics of the model.

- Logistic regression: A statistical tool for binary categorization. It uses the logistic function (sigmoid function) to calculate a probability between 0 and 1. The model calculates the probability of a binary response (diabetes: 0 or 1) based on one or more predictor variables.

- A Decision Tree is a supervised learning technique that divides data into subsets based on characteristic values, generating a tree structure. The branch nodes represent decision rules, the leaf nodes represent outcomes, and the internal nodes represent characteristics. A criterion determines which feature separates data at each node using the algorithm.

- Random forest: This ensemble learning method combines forecasts from hundreds or thousands of decision trees. Each tree is built using bootstrap aggregation (bagging) and feature randomization. Each forest tree is trained on a random subset of data and split using random features. The average (regression) or voting (classification) between all forest trees yields the final prediction.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): An effective supervised learning algorithm for classification and regression. It finds the best hyperplane to classify the data. Kernels turn non-linearly separable data into a higher-dimensional space. The kernel helps SVM manage complex data relationships.

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): A basic, non-parametric technique for classification and regression. Find the k-nearest neighbors of a data point in the feature space and assign their most common class label. K is a crucial hyperparameter that affects the performance of the model. KNN works effectively with simple decision boundaries and is intuitive.

- Naive Bayes, which is used for classification jobs. It assumes that all features in the dataset are independent of each other given the class label; the technique performs well in many real-world applications, including medical diagnosis, risk assessment, and text classification. Naive Bayes is useful for large datasets as it calculates the class probability based on prior knowledge and the likelihood of features. It is suitable for binary data. Naive Bayes is commonly used as a baseline classifier in machine learning due to its efficiency, simplicity, and capacity to handle high-dimensional data.

8.2. Risk Assessment and Predicting Complications (PHASE-B)

8.2.1. Dataset Preparation

Data extracted from Table 1 of PIMA were processed to assess the risk associated with biomarkers and the overall risk of diabetes separately, considering both the training and test datasets.

8.2.2. Risk Assessment Based on Biomarkers

The risk levels of each biomarker were assessed by considering the measurement levels reported by the American Diabetes Association [20]. Table 3 presents the classification of biomarker levels and the corresponding risk assignments. Each higher level of measurement is of higher risk.

Table 3.

Risk association matrix based on stratified biomarker thresholds.

Table 4 shows the weightage of contributions made by a biomarker to specific complications. The value of ‘0’ indicates the absence of contribution to specific complications.

Table 4.

Contribution of biomarkers to specific diabetic complications.

8.2.3. Assigning Weights to Biomarkers

The weights are assigned based on specific reasons that contribute to particular complications. Table 5 shows the reasons for the contribution in the case of gangrene complications. Table 6 shows the reasons for complications in the case of neuropathy, and Table 7 shows the reasons for complications in the case of cataracts. Similarly, the reasons for other complications can be prepared.

Table 5.

Reasons for assignment of weights to biomarkers in case of gangrene complication.

Table 6.

Reasons for assignment of weights to biomarkers in case of neuropathy complication.

Table 7.

Reasons for assignment of weights to biomarkers in case of cataract complication.

8.2.4. Learning ANN Model

A separate ANN model was created for each complication, taking into account the associated levels of biomarker risk and the overall risk of the complications. This model is used to predict the risk of a specific complication. Table 8 shows the details of the model’s learning and prediction accuracy, considering all ANNs, each representing a specific complication. Based on the patients’ risk levels of the biomarkers, complications can be predicted instantly from these tables.

Table 8.

Model design parameters and accuracy prediction of diabetic-related complications.

9. Results

9.1. Performance of ML Models Considering the Equalized Parameters

To ensure a robust evaluation of the models, we employed a combination of five-fold cross-validation and a training–test split (80:20 ratio) during the training and testing processes. The dataset was initially divided, with 80% allocated for training and 20% reserved as a separate test set to evaluate performance on unseen data. The key metrics of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score were calculated for each model.

Table 9 compares various machine learning models based on common parameters. After evaluating multiple machine learning models, the Random Forest algorithm emerged as the best-performing model due to its ability to accurately predict a patient’s diabetic state.

Table 9.

Performance comparison of different machine learning algorithms.

9.2. Comparing the Performance of ML Models Based on the Equal-Parameters Approach vs. Other Approaches

The proposed approach is the only one that considers common model parameters for the model training. Table 10 shows a comparative analysis of the proposed model with other learning models.

Table 10.

Comparison of model performance metrics for different algorithms.

9.3. Assessing Risk Due to Each Biomarker Relating to Different Patients

A sample of data extracted from the PIMA dataset is shown in Table 11. Risk due to each biomarker is computed using the risk assessment model presented in Section 8.2.

Table 11.

Sample data from the PIMA dataset.

The level of biomarkers for each patient is determined and assigned to a specific level of the biomarker, as shown in Table 12. The related risk is assigned to that specific biomarker.

Table 12.

Risk levels computed from sample records.

A diabetic patient may have many complications, and biomarkers contribute to each complication to a specific extent. Based on its contribution to complications, each biomarker is assigned a weight.

In the next step, the risk levels of the associated biomarkers are selected for each patient. The same is multiplied by the respective weights, and the combined overall risk is computed by averaging the weighted values across the maximum levels available for each biomarker. Table 13 shows the total risk calculation for gangrene complications.

Table 13.

Risk assessments in case of gangrene/DFU complication.

9.4. Overall Risk Calculations

Similarly, the overall risk levels for each complication are computed. Table 14 and Table 15 show the overall risk calculations considering two marker complications (cataract) and three marker complications (neuropathy).

Table 14.

Risk assessments in case of cataract complication.

Table 15.

Risk assessments in case of neuropathy complication.

10. Discussion

10.1. Discussion on Machine Learning Models

There is great variability in the assessment of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score for different machine learning models used for prediction by other authors, e.g., Chouhan et al. [6] and Salih et al. [59]. The variability arises because the optimisation is performed separately for each model. The model parameters used for learning vary drastically from method to method. There is no commonality in the model parameters. Thus, the results are not reliable for determining the optimal learning method for predicting diabetes. Each author selects machine learning (ML) models to compare to identify the most effective method. Each author separately considers different model parameters for optimization for each ML model. There is no commonality among the model parameters used by other authors. In this paper, a commonality is identified among the model parameters of different machine learning algorithms, and then the same approach is used to train the models; all four performance parameters have been estimated. From the table, it is evident that the variability among all machine learning models, considering all performance evaluation parameters, has been reduced, thereby making the evaluation more reliable and facilitating the optimal selection of a prediction model.

10.2. Discussion on Risk Assessment and Complication Predictive Models

Table 16 compares the proposed models with other models presented in the literature to predict the complications that a diabetic patient may face. The comparison is performed on the parameter AUC (area under the curve) as most of the models presented are based only on this parameter. The proposed models outscore all the other models presented in the literature, achieving an accuracy of nearly 100%. In the proposed model, L2 regularization is employed to prevent overfitting. No scaling is used, as risk levels are represented by numeric values in the range of 0–5. The sigmoid function is used in the output layer to express the existence or absence of a specific complication. The models are run using 500 epochs with a batch size of five to obtain optimal AUC values.

Table 16.

Comparative analysis of AUC for diabetic complication prediction using machine learning techniques.

11. Conclusions

Detecting diabetes in a patient and predicting the likelihood of various complications is crucial and urgent, allowing for immediate corrective actions to be taken.

The models comparing various machine learning models revealed that Random Forest produces the most accurate prediction regarding the existence of diabetes.

Comparative models have employed various machine learning methods. As such, there is no commonality among the various studies conducted. Every ML model is experimented with separately and optimized through the choice of model parameters. Training of the models is achieved using different approaches. This leads to non-uniformity; therefore, the comparison models do not reveal the proper suitability of a method for predicting diabetes.

In this paper, all the ML models have been trained on commonly related model parameters; the study considers all possible ML models and a comparison of the accuracy of the models has been presented, which revealed the non-existence of variability among the accuracy estimation, and the accuracy of Random Forest was slightly better, even though it took more time for processing.

Every biomarker contributes to the risk of complications that arise due to diabetes. The percentage of risk contribution varies from biomarker to biomarker. In this paper, a method for assigning risk due to each biomarker and its weight in contributing to a particular complication was presented, which contributes to an accurate prediction of 100% of complications due to diabetes.

This system gathers standard test results to diagnose diabetes mellitus in patients and offers predictions to help manage the disease effectively. In addition, it analyses the input parameters to assess the risk of developing diabetic complications, enabling proactive measures to prevent these potential problems. The system offers insight into the risks of the most important diabetes-related complications, namely, diabetic ketoacidosis, stroke, cardiomyopathy, nephropathy, diabetic foot ulcers/gangrene, retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and cataracts, by evaluating important metrics such as blood glucose levels, blood pressure, BMI, and age. Additionally, the system creates risk assessment and predictions of complications, helping patients to take precautionary measures. This strategy highlights the value of preventative care and sophisticated decision-making, which might improve quality of life for people with diabetes and empower patients and healthcare professionals.

12. Future Scope

The current study focuses on a machine learning-driven system for predicting diabetes complications and generating personalized recommendations.

In the future, this approach can be extended to address significant comorbidities associated with diabetes mellitus, which are crucial to managing and improving patient outcomes.

Research can be conducted to identify cognitive models for assigning weights to biomarkers that contribute to the various complications associated with diabetes.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.K.R.J., S.B.J., and S.S.B.; Software, S.S.B. and B.K.D.; Validation, S.S.B. and B.K.D.; Formal analysis, S.S.B., S.K.R.J., C.P.V., S.B.J., and B.C.V.; Investigation, S.S.B., C.P.V., S.B.J., B.K.D., and B.C.V.; Resources, S.K.R.J.; Data curation, B.K.D.; Writing—original draft, S.S.B., S.K.R.J., and S.B.J.; Writing—review & editing, S.K.R.J.; Visualization, B.C.V.; Supervision, C.P.V. and S.K.R.J.; Project administration, S.K.R.J. and C.P.V.; Funding acquisition, S.S.B., S.K.R.J., C.P.V., S.B.J., B.K.D., and B.C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received Partial funding from KLEF Deemed to be University Grant Number 25001, and the rest of the funding is met from the Authors’ resources.

Data Availability Statement

The publicly available PIMA data set is used for this research. Additional data generated are available as part of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Urgent Action Needed as Global Diabetes Cases Increase Four-Fold over Past Decades. World Health Organization. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-11-2024-urgent-action-needed-as-global-diabetes-cases-increase-four-fold-over-past-decades (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Olusanya, M.O.; Ogunsakin, R.E.; Ghai, M.; Adeleke, M.A. Accuracy of Machine Learning Classification Models for the Prediction of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Survey and Meta-Analysis Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, H.F.; Hamid, M.; Alaqail, H.; Seliaman, M.; Alhumam, A. Investigating Health-Related Features and Their Impact on the Prediction of Diabetes Using Machine Learning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Machine Learning Algorithm-Based Prediction of Diabetes Among Female Population Using PIMA Dataset. Healthcare 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deberneh, H.M.; Kim, I. Prediction of Type 2 Diabetes Based on Machine Learning Algorithm. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.S.; Varre, M.S.; Izuora, K.; Trabia, M.B.; Dufek, J.S. Prediction of Diabetes Mellitus Progression Using Supervised Machine Learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, A.; Jin, X.; Che, H. Prediction of Type 2 Diabetes Risk and Its Effect Evaluation Based on the XGBoost Model. Healthcare 2020, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, M.F.; Sabanci, K. A Novel Proposal for Deep Learning-Based Diabetes Prediction: Converting Clinical Data to Image Data. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoly, I.J.; Hoque, M.R.; Hasan, N. Data-Driven Diabetes Risk Factor Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms with Feature Selection Technique. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, H.; Ahuja, S. Deep Learning Approach for Diabetes Prediction Using PIMA Indian Dataset. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 Diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M. Pre-Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 635–643. [Google Scholar]

- Aponte, J. Prevalence of Normoglycemic, Prediabetic and Diabetic A1c Levels. World J. Diabetes 2013, 4, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecesoy, V.; Arici, H. Evaluation of Diabetes and Biochemical Markers. Nobel Tip Kitabevleri 2023, 37–43. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/evaluation-of-diabetes-and-biochemical-markers-6ywu0uku370a (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Hathaway, Q.A.; Roth, S.M.; Pinti, M.V.; Sprando, D.C.; Kunovac, A.; Durr, A.J.; Cook, C.C. Machine-Learning to Stratify Diabetic Patients Using Novel Cardiac Biomarkers and Integrative Genomics. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.S.K.; Tan, M. Diabetes Mellitus and Its Many Complications. Diabetes Mellit. 2020, 12, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Alian, S.; Li, J.; Pandey, V. A Personalized Recommendation System to Support Diabetes Self-Management for American Indians. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 73041–73051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wang, Q. A Personalized Diet and Exercise Recommender System for Type 1 Diabetes Self-Management: An in Silico Study. Smart Health 2019, 13, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, R.; Alluhaidan, A.S.; El Rahman, S.A. An Analytical Predictive Models and Secure Web-Based Personalized Diabetes Monitoring System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 105657–105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnosis. American Diabetes Association. Available online: https://diabetes.org/about-diabetes/diagnosis (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- AHO. Understanding Blood Pressure Readings. American Heart Association. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- AHO. Body Mass Index (BMI) in Adults, American Heart Association. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/losing-weight/bmi-in-adults (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Diabetes Facts & Figures. International Diabetes Federation. Available online: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Shin, J.; Lee, J.; Ko, T.; Lee, K.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.-S. Improving Machine Learning Diabetes Prediction Models for the Utmost Clinical Effectiveness. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, A.H.; Khan, T. Machine Learning-Based Application for Predicting Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2dm) in Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 199539–199561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadi, K.; Balachandran, W. Prediction Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus for Oman Prediabetes Patients Using Artificial Neural Network and Six Machine Learning Classifiers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A. Early Prediction of Diabetes Using an Ensemble of Machine Learning Models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y. Machine Learning Models for Data-Driven Prediction of Diabetes by Lifestyle Type. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuk, H.; Gim, J.; Min, J.K.; Yun, J.; Heo, T.-Y. Artificial Intelligence-Based Prediction of Diabetes and Prediabetes Using Health Checkup Data in Korea. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 2145644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnoodian, M.E.; Karimi Moridani, M.; Mokhber, H. Detection and Prediction of Diabetes Using Effective Biomarkers. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imaging Vis. 2024, 12, 2264937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, A.; Maritati, V.; Giannone, D.; Converting, D.; Galiano, A. LSTM DSS Automatism and Dataset Optimization for Diabetes Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabi-Marie-Sainte, S.; Aburahmah, L.; Almohaini, R.; Saba, T. Current Techniques for Diabetes Prediction: Review and Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, P. An Optimization-Based Diabetes Prediction Model Using CNN and Bi-Directional LSTM in Real-Time Environment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonia, J. Machine-Learning-Based Diabetes Mellitus Risk Prediction Using Multi-Layer Neural Network No-Prop Algorithm. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitriyani, N.; Syafrudin, M.; Ulyah, S.M.; Alfian, G.; Qolbiyani, S.L.; Anshari, M. A Comprehensive Analysis of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, US-PIMA Indian, and Trinidadian Screening Scores for Diabetes Risk Assessment and Prediction. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Data-Driven Machine-Learning Methods for Diabetes Risk Prediction. Sensors 2022, 22, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Han, Y.; Jang, K.; Kim, M. Early Prediction for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Using the Genetic Risk Score and Oxidative Stress Score. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Li, B.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Ding, N. A Prediction Model of the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in Individuals with Abdominal Obesity: Insights from the General Population. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 2022, 3555–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo-Marín, J.; Quetzalcóatl, T.A.; van Rooij, T.; Görges, M.; Wasserman, W.W. Prediction of Blood Risk Score in Diabetes Using Deep Neural Networks. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, T. Prediction of Diabetes Complications Using Computational Intelligence Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, Y.; Hua, R.-X.; Zou, L.-X. Prediction Models for Risk of Diabetic Kidney Disease in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serés-Noriega, T.; Perea, V.; Amor, A.J. Screening for Subclinical Atherosclerosis and the Prediction of Cardiovascular Events in People with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosak, L.; Svensek, A.; Lorber, M.; Stiglic, G. Artificial Intelligence Based Prediction of Diabetic Foot Risk in Patients with Diabetes: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Wu, A.; Hu, H.; Zhou, H.; Yang, M. Prediction of Diabetic Kidney Disease in Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 2023, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Cao, S.; Li, T.; Qin, Y.; Zhong, Y. Risk Prediction Models for Mild Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 2024, 4425–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. Design of Machine Learning Algorithms and Internal Validation of a Kidney Risk Prediction Model for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 2024, 2299–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X. Risk Prediction of Diabetes Progression Using Big Data Mining with Multifarious Physical Examination Indicators. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 2024, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D. Bayesian Network Analysis of Factors Influencing Type 2 Diabetes, Coronary Heart Disease, and Their Comorbidities. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toofanee, M.S. Dfu-Siam a Novel Diabetic Foot Ulcer classification with deep learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 98315–98332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, D. Diagnosis and Analysis of Diabetic Retinopathy Based on Electronic Health Records. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 86115–86120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Qaraqe, M.K.; Belhaouari, S.B.; Abdul-Ghani, M.A. Advanced Techniques for Predicting the Future Progression of Type 2 Diabetes. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 120537–120547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshan, M. An Innovative Ensemble Deep Learning Clinical Decision Support System for Diabetes Prediction. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 106193–106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkon, A.A. Evaluation of Feature Transformation and Machine Learning Models on Early Detection of Diabetes Mellitus. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 165425–165440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcely, B. Novel Biomarkers for Prediabetes, Diabetes, and Associated Complications. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2017, 2017, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazakis, N.; Kocsis, O.; Dritsas, E.; Alexiou, S.; Fakotakis, N.; Moustakas, K. Machine Learning Tools for Long-Term Type 2 Diabetes Risk Prediction. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 103737–103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Ma, X.; Zhang, R.X.; Yan, H. Oxidative Stress, Epigenetic Regulation and Pathological Processes of Lens Epithelial Cells Underlying Diabetic Cataract. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2023, 3, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhodari, M. Screening Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy in Diabetic Patients with Microvascular Complications Using Machine Learning: A 24-Hour Heart Rate Variability Study. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119171–119187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Rasheed, Y.; Azam, F.; Anwar, M.W.; Rahim, M.A.; Muzaffar, A.W. An Integrated Machine Learning Framework for Effective Prediction of Cardiovascular Diseases. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 106575–106588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, M.; Ibrahim, R.K.; Zeebaree, S.R.; Asaad, D.; Zebari, L.M.; Abdulkareem, N.M. Diabetic Prediction Based on Machine Learning Using PIMA Indian Dataset. Commun. Appl. Nonlinear Anal. 2024, 31, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagliati, A. Machine Learning Methods to Predict Diabetes Complications. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2018, 12, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, A.; Miertschin, S.; Young, A.; Mohanty, S.D. A Data-Driven Approach to Predicting Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease with Machine Learning. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, K.R. Evaluation of Machine Learning Methods Developed for Prediction of Diabetes Complications: A Systematic Review. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2023, 17, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kee, O.T. Cardiovascular Complications in a Diabetes Prediction Model Using Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L. Performance Assessment of Different Machine Learning Approaches in Predicting Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Using Electronic Health Records Data. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2021, 30, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seerapu, V.N.; Shirole, B.S.; Srilatha, P.; Penubaka, K.K.R>; Sivaraman, R. Lessons from Global Health Crises: The Role of Machine Learning and AI in Advancing Public Health Preparedness and Management. J. Neonatal Surg. 2024, 16. Available online: https://jneonatalsurg.com/index.php/jns/article/view/3596 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).