1. Introduction

Conversational agents are increasingly employed in education to promote active learning through dialogue rather than passive content delivery. In particular, Socratic chatbots, designed to guide students by prompting reasoning, encouraging reflection, and eliciting explanations, are gaining attention as scalable tools for supporting higher-order thinking. Such systems hold promise for fostering deeper engagement and for operationalizing frameworks like Bloom’s taxonomy, which describes the hierarchy of cognitive skills from Remember and Understand to Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create. This taxonomy was first introduced by Bloom [

1], then later adapted by Anderson and Krathwohl [

2]. By structuring interactions in ways that align with these cognitive levels, Socratic chatbots can provide opportunities for learners to articulate reasoning, test understanding, and engage in progressively complex mental processes.

Despite this potential, empirical research on the educational benefits of Socratic chatbots remains limited, particularly regarding how student–chatbot dialogues can be systematically analyzed to reveal patterns of cognitive engagement. This process is essential because it informs how educational chatbots are finetuned to improve their performance. Manual annotation of dialogues with Bloom’s taxonomy has been shown to provide valuable insight into learning processes, but it is labor-intensive and difficult to scale for large cohorts. This creates a need for automated approaches that can classify dialogue exchanges into cognitive categories reliably and at scale, thereby enabling learning analytics to capture fine-grained indicators of student reasoning. The Society for Learning Analytics Research [

3] provides a definition of learning analytics to be the collection, analysis, interpretation and communication of data about learners and their learning that provides theoretically relevant and actionable insights to enhance learning and teaching.

In this study, we address these gaps in three ways. First, we analyse a real-world corpus of 6716 Socratic student–chatbot exchanges from an undergraduate statistics course and formulate Bloom-level tagging of individual turns as a multi-label classification problem. Second, we propose and empirically evaluate a semi-supervised pseudo-labelling pipeline that combines sentence-embedding-based classical models (Logistic Regression, Linear SVM, XGBoost, MLP) with a fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini baseline, using calibrated per-class thresholds to generate high-confidence pseudo-labels from a small expert-annotated subset. Third, we demonstrate how the resulting Bloom profiles can support learning analytics of cognitive engagement in chatbot-supported learning, by comparing model families and examining the distribution of predicted cognitive levels across students and chatbot turns. Together, these contributions extend Bloom-based analysis beyond static texts to Socratic educational dialogues and offer a scalable approach for incorporating cognitive depth into learning analytics.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on educational chatbots and semi-supervised approaches to dialogue classification, with focus on learning taxonomy.

Section 3 describes the dataset of student–chatbot interactions and outlines the methodological framework, including the design of labeling functions and the weak supervision pipeline.

Section 4 presents the results of the classification experiments and evaluation against human annotations and discusses the implications of these findings for learning analytics, highlighting how automated cognitive labeling can inform instructional design and student support. Finally,

Section 5 concludes with reflections on the contributions, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Educational chatbots have grown increasingly common in higher education, offering scalable, on-demand interaction, personalized feedback, and extended learning outside of class hours [

4]. A recent systematic review by Labadze et al. found that students derive benefit from chatbots in three key areas: homework and study assistance, personalized learning experiences, and the development of various skills [

5]. However, as chatbots proliferate, a recurring concern is how deeply they engage students cognitively, whether they simply provide answers or stimulate critical thinking, and higher-level reasoning. Recent work on Socratic chatbots aims to address this concern. For example, Favero et al. describe a chatbot designed to offer thoughtful questioning rather than direct answers, prompting self-reflection [

6]. Similarly, Fakour and Imani examine how ChatGPT and human tutors differ in fostering critical thinking, emphasizing that while AI tools are useful, human tutors still often provide more tailored feedback and emotional support [

7]. Lai et al. use a Socratic chatbot to expose students’ self-regulated learning (SRL) behaviors through a process–action framework and epistemic network analysis; their focus is on metacognitive regulation rather than the fine-grained cognitive content of each utterance [

8]. A more recent systematic review by Debets et al. maps the primary uses of chatbots and points out that pedagogical depth, such as critical thinking and cognitive scaffolding, is less frequently examined than usability or informational assistance [

9]. Together, these studies highlight the potential of well-designed chatbots to engage students at a deeper level and underscore the accompanying challenge of how to measure such engagement in a principled way.

Bloom’s taxonomy remains a foundational theoretical lens for categorizing cognitive complexity and engagement, from lower-order thinking skills like Remembering and Understanding to higher-order ones like Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating. In education research, Bloom’s taxonomy has been widely used to shape assessments, learning objectives, and instructional design. In the NLP and learning analytics communities, however, much of the empirical work has focused on static educational artefacts. For example, Li et al. use a large set of over 21,000 learning objectives to train models to recognize cognitive levels, finding that separating binary classifiers for each level often outperforms multi-label classifiers [

10]. Almatrafi et al. demonstrate that GPT-4 can classify course learning outcomes into revised Bloom levels using tailored prompts, with the best prompting setup rivaling a BERT-based classifier on a 1000-item labeled dataset [

11]. Another line of work by Omar et al. and Huang et al. applies Bloom’s taxonomy to exam questions and classroom questions, respectively, demonstrating how feature-based and classical models can categorize question items, though with better performance on simpler, more frequent categories [

12,

13]. The tradition of analyzing interview questions also speaks to the desire to assess cognitive quality in quasi-dialogue contexts: Kazemi Vanhari et al. introduce a composite evaluation metric that accounts for both coverage and distribution of cognitive levels in a set of interview prompts [

14]. Closer to dialogic settings, Valcke et al. use Bloom’s taxonomy as a labeling tool for students’ online collaborative discussion messages, showing that asking students to tag their own contributions with Bloom levels can scaffold more active cognitive processing in computer-supported collaborative learning [

15]. These works demonstrate the usefulness of Bloom’s taxonomy for structuring educational measurement and for supporting reflection in discussion, while also highlighting the difficulties of automating classification—particularly as the cognitive level increases and data become sparse. Our work extends this line of research from static items and manually labeled discussions to Socratic educational dialogues, where student and chatbot utterances form multi-turn interaction traces, and we use a semi-supervised pseudo-labeling approach to cope with limited expert annotation in this richer setting.

By contrast, educational dialogues are dynamic and interactive. Cognitive moves unfold over multiple turns, with each utterance embedded in a local context of prior utterances, while Bloom-inspired heuristics are sometimes used informally to design chatbot prompts or discussion questions, there is comparatively little published work that applies Bloom’s taxonomy to continuous conversational exchanges by assigning cognitive labels to each student and chatbot utterance in situ. A further complication is that Bloom-level annotation in authentic settings is often a multi-label problem under conditions of label imbalance and limited expert annotation: an utterance can legitimately belong to more than one category (e.g., Understanding and Applying), and higher-order labels are typically much rarer than lower-order ones. This makes it difficult to rely solely on fully supervised learning with large, balanced, manually labeled corpora.

In the current digitalized classroom, where much of the learning occurs online and chatbot usage is often encouraged, gaining insights into cognitive engagement while learning with a chatbot becomes increasingly laborious if attempted by hand. At the same time, the automated classification of student and chatbot utterances into Bloom’s categories inherits the challenges of multi-label annotation, label imbalance, and limited expert labels. A recent survey by Li et al. summarizes theoretical and algorithmic foundations for learning when some labels are missing or partial, highlighting strategies such as modeling label correlations, reweighting losses, and inferring missing labels [

16]. More generally, semi-supervised multi-label algorithms have been proposed in domains such as video action detection, where pseudo-labeling, co-training, and judicious exploitation of unlabeled samples make it possible to extend models beyond small annotated cores [

17]. These approaches suggest that one can reduce dependence on large manually annotated corpora by leveraging weaker supervision or partial labels—an insight central to our work.

Pulling these strands together, there remain several gaps and opportunities that our work addresses. Namely, many studies on Bloom’s taxonomy focus on static texts—exam questions, learning objectives, or teacher-posed questions—but relatively few have attempted to automatically tag continuous conversational exchanges (student–chatbot turns) with Bloom’s taxonomy. Labeled data for such dialogues remain expensive, and while there are emerging approaches in educational and non-educational domains, there is limited published work applying semi-supervised, pseudo-labeling, or weak-labeling approaches specifically to educational dialogues, particularly in higher education settings. Finally, relatively few studies connect automatic tagging with actionable educational practices such as adapting chatbot responses, scaffolding learners, or providing feedback rather than simply retrospective analysis. In this work, we aim to narrow these gaps by performing Bloom’s taxonomy labeling of student–chatbot conversations using a semi-supervised pipeline that scales from a small expert-labeled subset to a larger corpus of real-world Socratic dialogues.

3. Methodology

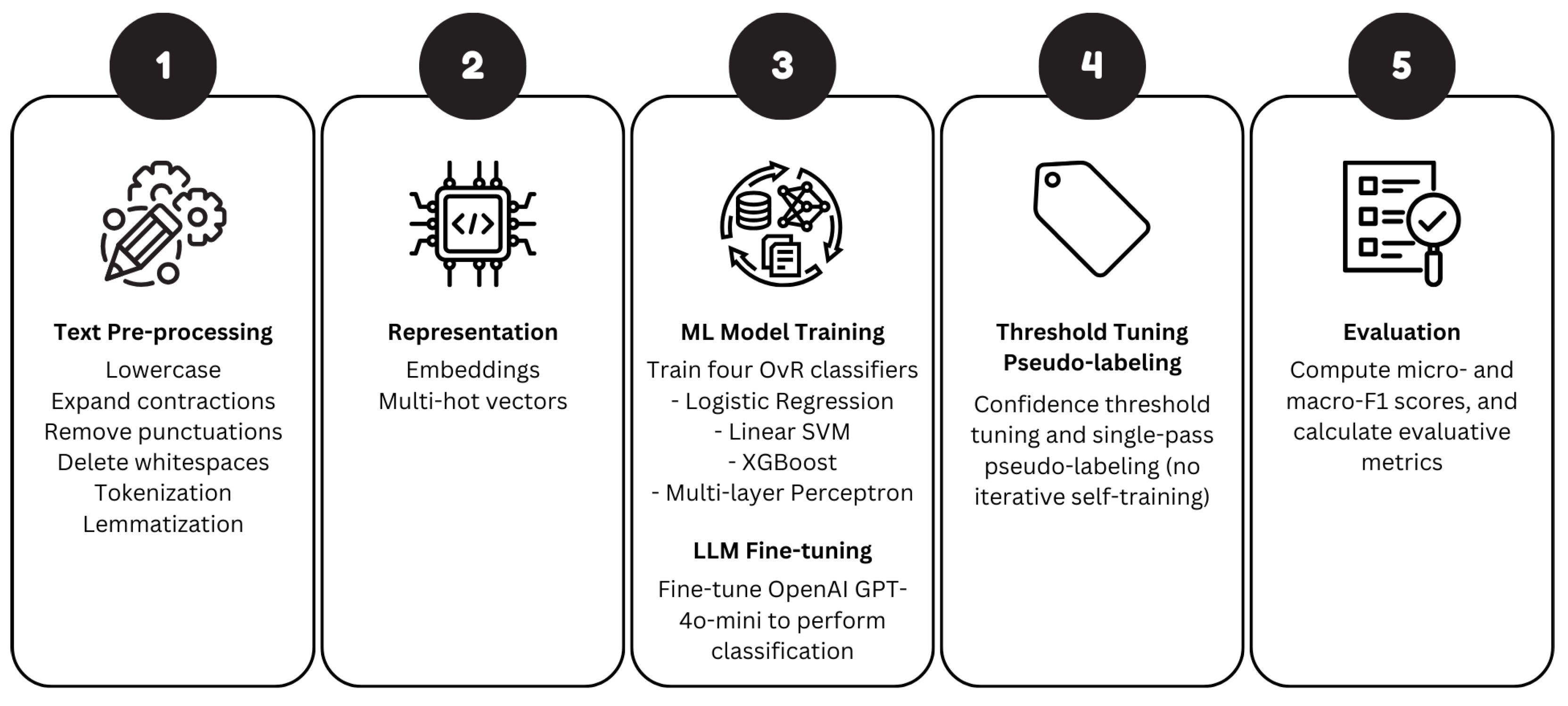

The Bloom-label tagging of chatbot–student exchanges is formulated as a multi-label text classification task, since each utterance may correspond to multiple Bloom cognitive levels. Only a subset of the corpus is expert-annotated, so our approach first trains and evaluates candidate models using the labeled subset only. We obtain out-of-fold class probabilities via 5-fold stratified cross-validation, and use these probabilities to tune class-specific confidence thresholds

that maximize F1 on each class’s precision–recall curve. After selecting the best-performing classifier, we retrain it once on all labeled data (with calibrated probabilistic outputs) and then apply the learned

thresholds to assign high-confidence pseudo-labels to the unlabeled exchanges in a single pass. Importantly, pseudo-labeled data are not fed back into retraining (i.e., no iterative self-training), avoiding confirmation-bias feedback loops while enabling scalable annotation. The full methodological pipeline is summarized in

Figure 1.

3.1. Data Sources and Structure

The dataset consists of 34 Excel workbooks, each containing the conversation log history for each participant. Each workbook contains:

SID: the anonymized student ID used purely to distinguish one student from another.

CID: the conversation ID to distinguish different chat sessions.

Content: the student’s prompt to elicit a response from the chatbot.

Reply: the chatbot’s generated response.

Among the 34 workbooks, three (Student 1, Student 2, and Student 3) were annotated by a single domain expert familiar with Bloom’s taxonomy, serving as the gold-labeled subset. These three workbooks (8.8% of the cohort) provide the only ground-truth Bloom labels used to train and evaluate the classifiers. The remaining 31 workbooks lack expert annotations and are labeled only via the pseudo-labeling procedure described in

Section 3.4. These pseudo-labels are used to illustrate how the trained model can be applied at scale to real classroom logs, but they are not treated as ground truth and are not used to compute any of the reported performance metrics.

These three workbooks were selected for expert annotation from the anonymized roster at the time of data preparation, specifically, we annotated the workbooks corresponding to the first three student IDs (SID) in the system. SIDs are assigned sequentially at account creation and are used only to distinguish one student from another; they are not ordered by task submission time, performance, or any other outcome variable. Bloom-level labeling of open-ended dialogue is labor-intensive and requires domain expertise, so annotating a small subset was necessary to keep the study feasible. This convenience sampling allowed us to establish an initial supervised model and calibrate confidence thresholds for pseudo-labeling of the remaining workbooks. The following are available for the three annotated workbooks:

The remaining workbooks lack annotations and are labeled via pseudo-labeling. This setup reflects practical educational contexts where manual annotation is expensive, and the majority of the chatbot logs remain unlabeled. This research was approved by the Nanyang Technological University Institutional Review Board (IRB-2023-735). No personally identifiable information was used in the study, and analyses focused exclusively on de-identified text.

3.2. Text Pre-Processing

Conversational data collected from real-world chatbot–student interactions present several challenges for computational analysis. Unlike curated corpora, these logs often contain informal phrasing, colloquial language, typographical errors, incomplete sentences, and spoken-language artifacts and short-hands. Such irregularities can reduce the effectiveness of machine learning models if unaddressed. To mitigate this, a multi-stage text pre-processing pipeline was implemented, designed to normalize and standardize the data while preserving features relevant to educational intent. The following pre-processing steps were performed: normalization, tokenization using Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) [

18], lemmatization using WordNet Lemmatizer [

19], and selective stopword filtering [

20,

21]. In the final step, we kept interrogatives such as “who”, “what”, “when”, “where”, “why”, and “how” as utterances with these words, primarily “why” or “how”, are often associated with higher-order levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. For this reason, a custom stopword list was constructed to remove semantically redundant words while retaining interrogatives that carry diagnostic value for cognitive classification. Through this combination, the raw conversational exchanges were transformed into a clean and standardized corpus. Importantly, this pipeline reduced surface-level noise while preserving linguistic cues that are strongly indicative of cognitive processes. The result was a dataset optimized for subsequent representation learning using sentence embeddings and for the downstream task of multi-label classification into Bloom’s categories.

3.3. Representation Learning and Classification

After preprocessing, each utterance in the dataset was transformed into a dense numerical representation suitable for machine learning. To capture semantic meaning at the sentence level, we employed the SentenceTransformer model all-MiniLM-L6-v2 [

22], a lightweight transformer-based encoder that balances computational efficiency with strong performance on semantic similarity tasks [

23,

24]. Each utterance, whether from the student or the chatbot, was encoded into a fixed-length 384-dimensional embedding vector. These embeddings preserved contextual information about the utterances, enabling downstream classifiers to distinguish between subtle variations in phrasing that correspond to different levels of Bloom’s taxonomy.

The annotated Bloom’s taxonomy labels, which can involve multiple categories per utterance, were transformed into machine-readable targets using a MultiLabelBinarizer. This procedure converted each set of categorical labels into a multi-hot vector, where each dimension corresponded to one Bloom category and a value of 1 indicated its presence [

25]. For example, an utterance tagged simultaneously as Understanding and Applying would be represented by a vector with ones in the corresponding dimensions and zeros elsewhere. This multi-label format ensured compatibility with classification algorithms while reflecting the possibility of overlapping cognitive processes.

For classification, we adopted a one-vs-rest framework, training a separate binary classifier for each Bloom category. Four distinct algorithms were implemented to explore different modeling capacities. The first was Logistic Regression, a linear model that served as a strong and interpretable baseline, capable of outputting calibrated probability estimates [

26]. The second was a linear Support Vector Machine (SVM), which seeks to maximize the margin between classes in the embedding space and is known for its robustness in high-dimensional settings [

27]. The third, XGBoost, is a gradient-boosted decision tree ensemble capable of modeling non-linear interactions among features [

28]. Finally, a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with fully connected hidden layers was trained to capture non-linear patterns in the embeddings through neural network representations [

29]. Collectively, the selected classifiers span a methodological spectrum, ranging from linear models with straightforward decision boundaries to more flexible non-linear models capable of modeling complex feature interactions.

All classical models were implemented in a one-vs-rest multi-label setting. Logistic Regression used max_iter = 2000, solver = liblinear, and class-balanced weighting. The linear SVM used C = 1.0 with class-balanced weighting, and its decision scores were converted to calibrated probabilities using sigmoid calibration with 5-fold internal cross-validation. XGBoost used gradient-boosted trees with n_estimators = 400, learning_rate = 0.05, max_depth = 5, subsample = 0.9, and colsample_bytree = 0.9; class imbalance was handled via scale_pos_weight computed from label frequencies. The MLP used two hidden layers of sizes 256 and 128 with ReLU activation, Adam optimization, batch size 32, a maximum of 300 epochs, and early stopping. Unless specified above, default library settings were retained.

Each classifier produced probabilistic outputs for each label, which were obtained using cross-validation to reduce overfitting and provide more reliable performance estimates. Since multi-label classification requires converting continuous probabilities into discrete predictions, we applied per-class threshold tuning. Specifically, for each Bloom category, the decision threshold was selected by sweeping along the precision–recall curve and identifying the cutoff that maximized the F1-score for that category. This approach allowed for tailored thresholds that balanced precision and recall according to the difficulty and distribution of each label. The final binarized predictions were then aggregated across utterances, and overall performance was assessed using micro-F1 (which weights frequent classes more heavily and reflects global performance) and macro-F1 (which treats all classes equally and highlights performance balance across categories) [

30].

In parallel with these classical approaches, we also developed a large language model (LLM) fine-tuning track. This component served both as a comparative benchmark and as a means of assessing whether modern pretrained models could outperform traditional methods in this domain. For this track, we selected the OpenAI GPT-4o-mini, a lightweight LLM suitable for fine-tuning on moderate datasets. For the LLM baseline, each labeled utterance was converted to a chat-formatted JSONL example and split 80/20 into training and validation sets with shuffling. We fine-tuned gpt-4o-mini-2024-07-18 for 3 epochs using a learning-rate multiplier of 0.3, and evaluated with deterministic decoding (temperature = 0.0). Fine-tuning was performed through the OpenAI supervised fine-tuning API. After training, the model was evaluated on the held-out validation set, with performance again measured using micro- and macro-F1 scores.

The integration of embedding-based classical classifiers with a fine-tuned LLM provided a comprehensive evaluation of methodological options for Bloom-label tagging. Whereas the classical models relied on compact sentence embeddings and explicit thresholding strategies, the LLM offered a more end-to-end approach capable of leveraging large-scale pretrained knowledge. The results from these complementary approaches were compared directly, providing insight into the trade-offs between lightweight traditional classifiers and fine-tuned transformer-based models.

3.4. High-Confidence Pseudo-Labeling of Unlabeled Exchanges

After model selection on the labeled subset, we labeled the unlabeled workbooks using a high-confidence pseudo-labeling step. We first obtained out-of-fold class probabilities on the labeled data via 5-fold stratified cross-validation. For each Bloom category k, we computed a precision–recall curve and selected a class-specific confidence threshold that maximized the F1-score for that category. Let denote the predicted probability. An unlabeled utterance x was assigned label k only when ; otherwise, the label was left unassigned.

Pseudo-labeling was performed in a single pass using the best-performing calibrated linear SVM retrained once on all labeled data. We did not perform iterative self-training (i.e., no pseudo-labels were added back into model retraining). This design prevents confirmation-bias feedback loops in which early model errors are repeatedly reinforced. In addition, probability calibration (sigmoid calibration for the SVM) and class-balanced training were used to improve threshold reliability for minority Bloom categories.

It is important to note that, because the pseudo-labeled workbooks do not have expert Bloom annotations, they are used only as a target corpus for applying the trained classifier and for downstream descriptive analyses. All micro- and macro-F1 scores reported in this paper are computed exclusively on the three gold-labeled students. In this sense, “high-confidence” refers to the use of calibrated, class-specific probability thresholds on the source domain of labeled data, rather than to any empirically verified error rate on the remaining 31 students, for whom ground-truth labels are unavailable.

4. Results & Discussion

The micro- and macro-F1 scores of the classical classifiers and the fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini are summarized in

Table 1. Across models, micro-F1 ranged from

to

, while macro-F1 ranged from

to

. Among the classical classifiers trained on sentence embeddings, Logistic Regression achieved the highest micro-F1 at

, closely followed by the MLP (

) and the Linear SVM (

). XGBoost registered the lowest micro-F1 at

. However, the relative ordering changed when considering macro-F1. The Linear SVM outperformed the other classical classifiers with a macro-F1 of

, slightly higher than Logistic Regression (

) and XGBoost (

), while the MLP trailed with a macro-F1 of

. By contrast, the fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini achieved the highest overall micro-F1 of

, outperforming the best classical baseline by

. However, this came at the cost of a much lower macro-F1 of

, approximately

below the Linear SVM. This result challenges the emerging default assumption that LLMs are universally superior for all NLP classification tasks, especially in the presence of strong class imbalance, and highlights scenarios where classical models remain preferable.

The divergence between micro- and macro-F1 highlights the challenge of class imbalance among Bloom’s labels and the varying sensitivity of models to minority categories. The fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini’s strong micro-F1 indicates its ability to model the dominant patterns well, particularly the more frequent lower-order categories such as Remembering and Understanding. However, its relatively weak macro-F1 suggests poorer generalization to underrepresented labels, namely the higher-order categories. In contrast, the Linear SVM and Logistic Regression, supported by per-class threshold calibration, demonstrated steadier performance across Bloom levels, achieving higher macro-F1 scores. This suggests that these models maintain better balance between frequent and rare classes, even if their aggregate accuracy lags behind the LLM. The MLP’s comparatively low macro-F1 points to either mild overfitting or poorer calibration of probabilities on minority classes, while XGBoost sits between the linear baselines and the neural network across both metrics.

Two practical implications emerge from these results. First, if the analytic goal is to maximize overall correctness weighted by prevalence, then the fine-tuned LLM is clearly the most attractive option. Its superior micro-F1 underscores its strength in capturing the dominant conversational patterns, making it suitable for high-level summaries of student–chatbot exchanges. Second, if the aim is to achieve equitable performance across all Bloom categories, then the calibrated Linear SVM model is preferable. Their higher macro-F1 scores show that they are less biased toward the majority classes, an important consideration when the educational goal is to track higher-order cognitive skills that are rarer but more pedagogically significant. In the context of educational chatbot use, however, the trade-off looks different. Here, the ability to reliably detect the rarer higher-order categories is arguably more valuable than capturing the majority classes, because these moments represent opportunities for the chatbot to scaffold learning and push students toward deeper engagement. For example, when a learner moves from Understanding to Analyzing, the chatbot can respond with targeted prompts that encourage Evaluating or Creating. In this setting, a model such as the Linear SVM, despite its lower micro-F1, would be advantageous, since its stronger macro-F1 provides more consistent coverage of the full Bloom spectrum. That coverage allows the chatbot not only to mirror the student’s current level of reasoning but also to strategically extend it. Thus, while the fine-tuned LLM offers efficiency for broad analytics, calibrated classical models may prove more effective for pedagogical interventions in real-time dialogue.

However, beyond comparing how the models label these conversation exchanges, it is instructive to also examine the distribution of the model-predicted labels as a proxy for the quality of student conversation and the help that chatbots are providing the students. The comparison between these predicted label frequencies is shown in

Figure 2. In this figure, the “Unlabeled” category is a technical bucket capturing utterances for which no Bloom level exceeded its calibrated confidence threshold; it does not represent a cognitive level in Bloom’s taxonomy. Accordingly, all distributional analyses and percentages reported are computed over the six Bloom categories only.

Because the majority of utterances are pseudo-labeled rather than human-annotated, the analyses in this section should be interpreted as exploratory, model-based summaries rather than confirmatory hypothesis tests about the true underlying cognitive distributions of students and chatbots. To quantify discrepancies between predicted profiles, we computed statistics of independence across the six Bloom categories (excluding the “Unlabeled” class) to compare (i) student vs. chatbot distributions and (ii) Linear SVM vs. fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini distributions. The resulting values (student–chatbot: 1182.68 for the SVM and 1015.62 for GPT-4o-mini; SVM–GPT contrasts within each role: 166.06 for students and 249.22 for chatbots) indicate that the models assign Bloom levels differently across these conditions. However, we refrain from attaching classical p-values to these statistics, since pseudo-labeled data violate the assumption that each count reflects ground-truth annotation.

As a complementary, effect-size style measure, we computed Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence [

31] between SVM- and GPT-predicted distributions, yielding

for student utterances and

for chatbot utterances. These small divergence values suggest that the overall cognitive profiles predicted by the two models are broadly similar, with modest but systematic shifts. A KL divergence of 0.064 suggests that the two models produce highly similar overall cognitive profiles, with differences equivalent to a slight redistribution of probability mass across Bloom categories—insufficient to alter the main finding of lower-order dominance, but indicative of model-specific biases in classifying certain higher-order levels.

To better understand the performance gap between the Linear SVM and the fine-tuned GPT-4o-mini on minority classes, we conducted a qualitative error analysis. We sampled examples from the test set involving minority labels and categorized them accordingly.

From

Table 2, we observe that in many minority-class examples where the SVM is correct but GPT-4o-mini is not, the input contains sparse but distinctive lexical cues such as “what”, “how”, and “when”. In these cases, the linear decision boundary learned from bag-of-words style features seems to capture strong associations between these cues and the minority label. In contrast, GPT-4o-mini more frequently predicts majority or semantically related high-frequency classes, even when minority-specific cues are present. This behaviour suggests that the fine-tuned LLM sometimes over-regularizes toward frequent classes or relies on more generic semantic similarity rather than exploiting rare but decisive lexical evidence in imbalanced settings. There are also examples where GPT-4o-mini succeeds while the SVM fails. These typically involve longer inputs or cases where the minority label depends on nuanced context, which are more naturally handled by the LLM’s contextual representation. Overall, this qualitative analysis explains the macro-F1 divergence, SVM better exploits highly discriminative sparse features that characterize minority classes in our dataset, while GPT-4o-mini’s strengths lie in more context-dependent reasoning but are offset by a tendency to over-predict majority classes under imbalance.

The results presented in

Figure 2 have direct implications for learning analytics, albeit with important caveats. First, within our current model-based labeling, Understanding dominates the labeled student utterances (82–92%, once the Unlabeled category is excluded), indicating that the classifiers tend to assign a large majority of student turns to lower-order Bloom levels. Taken at face value, this pattern is consistent with the idea that many chatbot-mediated interactions revolve around consolidating understanding rather than engaging in higher-order reasoning. However, this interpretation must be seen as tentative, because the Bloom labels for the 31 pseudo-labeled students have not been independently validated and the models themselves are trained on a small, imbalanced expert-labeled subset. An equally plausible explanation is that the classifiers are better at recognizing surface patterns associated with Understanding and systematically under-detect more nuanced higher-order thinking in the remaining dialogues.

From an analytics perspective, if the model-predicted distributions are at least approximately accurate, dashboards or performance summaries based only on aggregate participation would risk overstating the depth of learning taking place. For instructors and researchers, identifying this skew in the model-based profiles is still useful, because it flags a potential concentration of activity at lower-order levels and highlights the need for both richer human validation and improved models before drawing strong conclusions about educational effectiveness.

Second, the relative scarcity of higher-order utterances (collectively ≤10% of labeled instances) highlights a blind spot in the current chatbot. These higher-order categories are exactly the dimensions most educators want to foster and monitor. Their underrepresentation not only depresses macro-F1 as models struggle to learn from limited examples, but also limits the analytics available to assess whether a chatbot is genuinely scaffolding advanced reasoning. In other words, the imbalance in

Figure 2 translates directly into an imbalance in what learning analytics can reliably report. Finally, the relatively high proportion of unlabeled student utterances (≈44–48%) points to the prevalence of ambiguous, meta-communicative, or off-task dialogue in real-world educational settings.

For learning analytics, this signals both a challenge and an opportunity. On the one hand, it complicates straightforward Bloom-level tracking, as not every utterance maps neatly onto a cognitive category. On the other, it provides a window into learner affect, engagement, or strategy use; dimensions that may be incorporated into richer analytics frameworks. To address the observed class imbalance, particularly the underrepresentation of certain categories, future work will focus on both data-centric and model-centric strategies. On the data side, targeted augmentation methods, for example, paraphrasing, back-translation, or synthetic dialogue generation, can be applied to enrich the training set with more diverse instances of higher-order reasoning, which is lacking. On the modeling side, hybrid ensemble architectures offer a promising direction such as using a fine-tuned LLM to classify majority categories with high confidence, while calibrated linear models (e.g., SVM or Logistic Regression) could be invoked for minority or ambiguous cases. Such an approach would leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms, improving robustness and coverage across the full Bloom hierarchy.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a reproducible pipeline for tagging chatbot–student conversational exchanges with Bloom’s cognitive labels, combining a calibrated classical machine learning track with a fine-tuned, lightweight large language model. By leveraging high-confidence pseudo-labeling, the approach was able to make effective use of a small set of expert-labeled workbooks while scaling across a larger corpus of real-world chatbot logs. The evaluation demonstrated clear trade-offs between model families. Distributional analyses confirm modest model-family differences in the model-predicted Bloom profiles, with a pronounced skew toward lower-order cognitive levels appearing robust across students and chatbots under our current classifiers. However, because pseudo-labels for the unlabeled students have not been independently validated and the models are trained on a small, imbalanced annotated subset, these distributions should be interpreted as exploratory, model-based estimates rather than definitive measurements of the chatbot’s educational effectiveness. At the same time, classical models provide more equitable coverage of the rarer but pedagogically significant Bloom levels, such as Analyze, Evaluate, and Create. We note, however, that the same issues faced by previous works, where an imbalance of labels leads to a significant decrease in F1 scores, continue to remain true in our case. This continues to be a pressing problem that requires further methodological exploration.

A principal limitation of this study is dataset scale and labeling coverage. The corpus comprises 34 students from a single course, and the gold-labeled subset is drawn from only three students (8.8% of the cohort). Moreover, the three labeled workbooks were chosen for expert annotation from the first three student IDs in the anonymized roster. SIDs are assigned sequentially at account creation and are not tied to submission time or performance, but with only three annotated students we cannot guarantee that this subset is fully representative of the cohort. Although this reflects realistic annotation constraints in classroom analytics, it may bias the classifiers toward the discourse patterns and cognitive styles of those particular students, increasing the risk of overfitting to a narrow sample. The pseudo-labels assigned to the remaining 31 students’ utterances should therefore be interpreted as model-generated estimates, suitable for aggregate analytics and exploratory visualization, but not as validated ground truth. Future work should expand expert labeling to involving multiple annotators on a larger and more diverse subset of students (ideally across multiple courses/institutions) and evaluate robustness with student-level splits. Additionally, to facilitate robust learning analytics, fine-grained performance analysis for rare higher-order classifications, such as per-class precision and recall, can be computed.

From a learning analytics perspective, the results underscore both the promise and the limitations of automated Bloom-level tagging. On the one hand, the pipeline enables moving beyond surface indicators of engagement toward more cognitively meaningful analytics, thereby allowing dashboards and research studies to quantify the distribution of learning processes in real time. On the other hand, the strong skew toward lower-order categories observed in the dataset constrains the ability of models to reliably detect higher-order thinking, precisely the forms of reasoning most valued in educational practice. This highlights the need for continued attention to data balance and curation, particularly by enriching training resources with examples of advanced reasoning and creative synthesis. Looking forward, several extensions appear promising. Hybrid strategies that combine the high-confidence predictions of fine-tuned LLMs with the steadier per-class calibration of linear models may offer the best of both worlds. Likewise, class-aware fine-tuning, balanced sampling, and targeted augmentation of minority categories could directly improve the coverage of higher-order Bloom levels. More broadly, embedding Bloom’s taxonomy into chatbot analytics represents a step toward richer, cognitively grounded forms of learning analytics. By operationalizing not only how much learners interact but also at what level they think, the proposed pipeline contributes to the growing vision of analytics as a tool for supporting deeper learning and more effective pedagogical design.

The ability to automatically identify the cognitive level of a student’s utterance creates important opportunities for adaptive pedagogy. When the chatbot recognizes that a learner is operating at a lower-order level, such as Remembering or Understanding, it can intentionally introduce prompts or follow-up questions that encourage movement toward higher-order skills like Analyzing, Evaluating, or Creating. Conversely, when a learner is already reasoning at a more advanced level, the chatbot can either match the student’s depth to sustain engagement or strategically scaffold them further by posing increasingly complex, open-ended questions. In this way, Bloom-level tagging does more than classify conversations; it provides a foundation for dynamic conversational strategies that nudge students into deeper forms of cognitive engagement with the course material. A natural next step is to integrate the classifier into the live chatbot loop, maintaining a running estimate of each student’s Bloom level and adjusting Socratic prompts in real time; future work should implement and evaluate such Bloom-aware dialogue policies in classroom trials to test effects on learning outcomes and student experience.