1. Introduction

Monitoring fruit maturity is crucial for determining the optimal harvest time to achieve the best balance between eating quality (flavour, sweetness) and the durability required for shipping and handling. Harvesting too early results in tasteless, underripe fruit, while harvesting too late leads to overripe, soft fruit that spoils quickly and has a very short post-harvest life [

1]. The firmness of the peach fruit is closely related to harvest maturity and is the main factor that affects the post-harvest storage characteristics of the fruit. Firmness has been identified as the most reliable parameter for determining maturity compared to other quality indicators [

2]. Peach firmness is typically measured using a penetrometer, which applies a standardized force to penetrate the fruit flesh. In this research, peach firmness is measured using a penetrometer equipped with an 8 mm wide cylindrical probe, where after skin removal at four equatorial sides maximum penetration force is being recorded [

3,

4]. This presents a significant limitation, as this maturity assessment method is destructive to the fruit. Alongside mechanical tests, dielectric properties have also been explored for maturity evaluation. For instance, while dielectric property measurements have proven to be reliable predictors in models for evaluating peach maturity, traditional dielectric measurement methods also require inserting electrodes into the fruit. This makes the technique equally destructive and impractical for high-throughput sorting [

5]. Therefore, there is a need for an accurate measure of fruit maturity based on parameters that can be measured non-destructively.

Based on a literature review, the primary non-destructive methods for assessing fruit maturity can be categorized into several groups: Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS), Computer Vision, and other techniques such as acoustic methods and electronic nose. The complex data obtained from these techniques are subsequently processed by advanced machine learning methods, which translate the information into specific maturity indicators such as fruit firmness and soluble solid content, both of which are commonly associated with peach maturity.

As early as 2009, it was demonstrated that portable Vis-NIR spectroscopy can accurately and non-destructively predict apricot fruit quality attributes such as firmness and soluble solids content. The results showed a strong correlation between spectral data and internal quality, confirming the method’s potential for real-time, in-field maturity assessment [

6]. Today, this technology effectively combines VIS/NIR spectroscopy with machine learning models (such as decision trees and gradient boosting) for non-destructive assessment of grape ripeness. The authors achieve high accuracy in predicting key ripeness indicators, including anthocyanin content, soluble solids content, and titratable acidity, confirming the method’s efficiency for in-field analysis [

7].

In parallel with spectroscopic approaches, computer vision and deep learning techniques have been used to develop one-stage instance segmentation models utilizing architectures such as Mask R-CNN and YOLO to detect and classify the maturity stages of peaches. This method demonstrates high classification accuracy and offers a robust solution for the automated harvesting and sorting of peaches under real-world orchard conditions [

8].

The use of machine learning, and especially neural networks, in fruit maturity prediction is becoming increasingly common due to their ability to perform accurate and automated classification based on visual or sensor data.

The application of deep learning is not limited to peaches. For instance, a study on bananas [

9], which are also highly perishable, focuses on the development of deep learning models for maturity classification using convolutional neural networks (CNN) and the AlexNet architecture applied to image data. The emphasis is on computer vision, data augmentation, and implementation in the Keras/TensorFlow framework for robust and accurate classification. The proposed CNN model achieved up to 99.36% validation accuracy, outperforming AlexNet in most evaluated scenarios.

However, these are methods that rely on neural network models for fruit maturity prediction based almost exclusively on images. Few models focus on non-destructive prediction using only tabular data, even though sensors providing such features are significantly cheaper, and model training is considerably faster.

A study by Ropelewska [

10] explores the use of non-destructive sensor measurements combined with machine learning models, including Random Forest, Naive Bayes, k-NN, and Decision Tree, for classifying peaches at different maturity stages. Based on tabular data such as firmness, skin color (L*, a*, b*), size, and weight collected via low-cost sensors, the Random Forest model achieved classification accuracy exceeding 90%. These findings highlight that low-cost, non-destructive sensing technologies paired with machine learning provide an efficient and reliable approach for maturity prediction in peaches.

Another study [

11] aligns well with other machine learning approaches for fruit maturity prediction, as it relies exclusively on structured tabular data rather than image-based inputs. By evaluating models such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, XGBoost, and Decision Trees on physicochemical measurements of oil palm fruit, it confirms that high predictive performance can be achieved without visual features. In particular, the XGBoost model demonstrated superior accuracy, reinforcing the value of ensemble methods in agricultural classification tasks. While these classical models have shown strong performance, the question remains whether newer, specialized neural network architectures for tabular data can offer superior performance or different advantages such as interpretability.

In a recent study [

12], the performance of eight machine learning models was evaluated for predicting peach maturity using exclusively non-destructive tabular features, including fruit dimensions and skin color parameters. Following feature selection with the LASSO method, the artificial neural network (ANN) model demonstrated the highest classification accuracy among the tested approaches.

As neural network models demonstrated the highest accuracy in the study [

12], a review of the literature identified three neural architectures that have shown strong performance on tabular data: TabNet, NODE, and SAINT [

13,

14,

15].

TabNet employs a sequential attention mechanism to select relevant features at each decision step, enabling both interpretability and efficient representation learning [

16]. NODE integrates differentiable decision trees into deep networks, leveraging the strengths of ensemble methods while retaining end-to-end trainability [

17]. SAINT introduces a transformer-based architecture with both feature-level and intersample attention, capturing complex dependencies within and across data instances. These models represent a new generation of deep learning methods specifically optimized for structured/tabular datasets, often matching or surpassing traditional gradient boosting techniques in predictive performance [

18].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the applicability and performance of recent neural network architectures specifically optimized for tabular data in the context of non-destructive peach maturity prediction. By comparing TabNet, SAINT, and NODE on a real-world dataset of sensor-based measurements, this research seeks to identify models that combine high classification accuracy with efficient training and potential for integration into autonomous harvesting systems. Ultimately, the study contributes to the development of reliable, low-cost, and scalable machine learning solutions for decision support in precision horticulture.

Unlike previous studies that primarily relied on classical machine learning algorithms or deep learning models applied to image data, this research focuses on neural network architectures specifically designed for tabular inputs. While earlier work demonstrated the feasibility of using low-cost sensor data with models such as Random Forest or ANN, this study systematically compares advanced tabular-specific neural networks (TabNet, SAINT, and NODE), highlighting their potential to achieve high accuracy while preserving interpretability (TabNet) and efficiency in non-destructive fruit maturity classification.

In this study, the Index of Absorbance Difference (iad) emerged as a particularly strong predictor of peach maturity, often dominating model performance. However, although iad sensors can be integrated into industrial and drone-based systems, they are relatively expensive. Since iad also represents a dominant predictor of maturity, additional experiments were conducted to evaluate model performance when this strong feature was excluded and when models were trained on compact subsets of the most informative non-destructive variables. The results demonstrated that even in the absence of iad, and when relying on reduced feature sets, the evaluated neural network models achieved satisfactory classification accuracy, suggesting that reliable maturity prediction can be accomplished using features derived from low-cost sensors performing non-destructive measurements.

2. Materials and Methods

All data processing, analysis, and model development were performed using the Python programming language (v3.9). Key libraries included Pandas (v2.3.1) for data manipulation, Scikit-learn (1.7.1) for machine learning, and Matplotlib (v3.10.3) for data visualization, together with PyTorch (v2.7.1)-based libraries for neural network modelling (including pytorch_tabnet, node-tabular, and an open-source implementation of SAINT).

2.1. Dataset Description

The generation of dataset containing this type of measurement is a resource-intensive process, demanding significant investment in both time and labor. Consequently, the dataset utilized in many of the aforementioned studies are of a relatively limited scale, particularly within the context of neural network applications. For instance, the dataset presented in [

12] comprises 180 samples, whereas the one in [

2] includes merely 120 measurements. The variables used in the former study are marked with a (+) symbol in

Table 1, as they correspond closely to those measured in the present work and are therefore directly comparable.

The dataset employed in this research comprises 701 samples of peach fruit (

Prunus persica), each characterized by 44 variables utilized for classifying maturity stages. All samples were collected from a single cultivar (‘Redhaven’) grown at one geographical location, which may limit the generalizability of the models to other cultivars or growing conditions. Therefore, model performance should be independently validated before application to different peach varieties or environments. The data are maintained in a CSV file format. In USA lack of taste and failure to ripen are the main reasons that limit stone fruit consumption [

19]. Peaches, as being susceptible to bruising due to fleshy mesocarp, are usually harvested earlier to last longer and withstand manipulation. However, although they are climacteric fruit, there is a connection between on-tree physiological maturity and the development of key fruit quality traits [

20]. Hence, too early harvest can lead to consumer dissatisfaction and reduced further consumption. In order to meet the quality standards, peach fruit at harvest should not exceed firmness higher than

(Ramina et al. [

21], according to Neri et al. [

22]). Hence this firmness threshold was used in this study primarily to address consumers growing dissatisfaction with peach fruit eating quality. Following this main maturity segmentation presented in this paper further ones should be also carried in packinghouses (overripe, ready to eat, ready to buy and storable peaches).

The remaining 43 variables function as predictors and are composed of a diverse array of physical, colorimetric, biochemical, and electrical measurements. These can be broadly categorized into the following groups:

Physical and Morphometric Attributes: vol: Peach volume, mass: Peach mass, firm: Fruit firmness

Biochemical and Sensory Features: tst: Soluble solids content, ta: Titratable acidity

Colorimetric Descriptors: udb: share of additional color, md_X, moo_X, mop_X: Maximum values of additional color, ground, and petiole ground color

Impedance-Based Electrical Properties: zs_nd, th_nd: Zs and Ts components (non-destructive), zs_d, th_d: Zs and Ts components (destructive), zs_nd_X, th_nd_X: non-destructively obtained Ts and Zs adjusted for deviation from mean volume

Ripening Index: iad: index of absorbance difference

With a clearly defined categorical target and a heterogeneous mix of continuous, ordinal, and categorical features, this dataset is highly suitable for the development and evaluation of supervised machine learning models for fruit quality assessment and maturity classification.

A total of 701 fruits at various ripening stages were analyzed during this period, resulting in a dataset comprising 701 samples with 43 predictor variables. The dataset does not include the complete photographic set from four different angles nor the multispectral imaging results, which were conducted only on one-third of the fruits. Nevertheless, it provides a highly comprehensive representation of the morphological and physicochemical characteristics of peaches. The list of all variables, including their dataset names and descriptions, is provided in

Table 1. The (+) symbol in the description indicates variables that were also used in the study by Ljubobratović et al. [

12], representing comparable measurement features. Variables

th_nd_X and

zs_nd_X were adjusted based on deviation from the average fruit volume. All above mentioned variables, with exception of destructive and non-destructive dielectric properties, were measured as reported in our previous study [

23]. While dielectric properties were conducted on all fruits in two orthogonal orientations: first along the narrower longitudinal axis of the peach, and subsequently along the wider transverse axis. All measurements were carried out using an ET430 handheld LCR meter with a drive voltage of 600 mV and a frequency of 10 kHz, parameters previously identified as optimal for characterization of peach physicochemical properties [

24]. Additionally, the

udb assessment was performed using a slightly modified protocol, which included an additional category (0) denoting peaches exhibiting no additional coloration.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

Prior to model training, the dataset underwent a structured preprocessing pipeline. The raw data were first imported from a semicolon-delimited CSV file with comma used as the decimal separator. A non-informative identifier column (br) was removed. The target variable (ripe) was isolated, while the remaining 43 variables were used as predictors. Categorical features were encoded using the OrdinalEncoder, and all numerical features were standardized to zero mean and unit variance using the StandardScaler. The fitted encoder and scaler were retained for future use on test data to ensure consistency in data transformation.

To ensure robust model development and to avoid any form of information leakage, all model selection procedures were performed exclusively within the training portion of the data. After the initial stratified train-test split, the 75% training subset (525 samples) was further partitioned using stratified 5-fold cross-validation. In each fold, approximately 80% of the training set (420 samples) was used for model training, while the remaining 20% (105 samples) served as a validation fold for monitoring training behaviour, tuning hyperparameters, and applying early stopping.

Importantly, no sample from the independent 25% test set was ever used during cross-validation or any phase of model construction. This ensures that all reported test-set results reflect true model generalization on entirely unseen data.

Train-Test Partitioning

Before any model development, the complete dataset of 701 Redhaven peach samples was partitioned into a stratified training-test split. A total of 75% of the data (525 samples) was allocated to the training set, while the remaining 25% (176 samples) formed an independent held-out test set. The split was stratified with respect to the binary maturity label to preserve the original class distribution in both subsets. The test set was not used at any stage of model development, including feature preprocessing, hyperparameter tuning, early stopping, or model selection. All preprocessing steps (imputation, encoding, and standardization) were fitted exclusively on the training set and subsequently applied to the test set using the same fitted parameters, ensuring a fully isolated and unbiased evaluation on unseen data.

2.3. Models Description

Three neural network models specifically designed for tabular data were trained on the preprocessed dataset: TabNet, NODE, and SAINT. Each model embodies a distinct architectural approach to learning from structured data. TabNet employs sequential attention for feature selection and interpretability [

13], NODE utilizes ensembles of differentiable oblivious decision trees [

14], while SAINT incorporates both self-attention across features and intersample attention across rows [

15].

All models were trained exclusively on the training portion of the dataset (75% of the full dataset; 525 samples). Model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and early stopping were performed using stratified 5-fold cross-validation applied only within the training subset. The independent 25% test set (176 samples) was withheld throughout the entire development process and used solely for final evaluation. Detailed architectural and implementation settings for each model are described below.

TabNet is a deep learning architecture specifically designed for tabular data. It utilizes a sequential attention mechanism that enables the model to focus on the most relevant features at each decision step. This structure not only enhances predictive performance but also provides interpretability through feature importance masks [

13]. In our implementation, the

TabNetClassifier from the

pytorch_tabnet library was used. The model was trained for 200 epochs with the following hyperparameters: 3 decision steps, 8-dimensional feature transformer, 8-dimensional attention transformer, and a batch size of 256. Early stopping was applied with a patience of 20 epochs.

NODE (Neural Oblivious Decision Ensembles) replaces traditional decision tree ensembles with differentiable oblivious decision trees, where each decision node applies the same split across all samples. This architecture enables end-to-end gradient-based optimization while preserving tree-like inductive biases [

14]. The model was implemented using the

node package by Popov et al. [

17] and trained using the inner 5-fold cross-validation procedure applied only to the training subset. No information from the test set was used during training, validation, hyperparameter selection, or early stopping. The architecture consisted of an Oblivious Decision S-Tree (ODST) layer with 160 trees, each having a depth of 7, a batch size of 256, and a maximum of 200 training epochs with early stopping (patience = 25). Optimization was carried out using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001.

SAINT (Self-Attention and Intersample Attention Transformer) extends the transformer architecture to tabular data by combining both self-attention across features and intersample attention across rows. This dual-attention mechanism allows the model to capture complex intra- and inter-feature dependencies [

15]. We used an adapted implementation based on the open-source SAINT repository. The model was trained for up to 500 epochs with a batch size of 128, a transformer dimension of 64, 6 attention layers, and 8 attention heads, with a dropout rate of 0.05. Categorical features were embedded, and numerical features were normalized. The training pipeline included label smoothing, stochastic depth, and CutMix augmentation (lambda = 0.1). Optimization was performed using the AdamW optimizer (learning rate = 0.0001, weight decay = 0.01), with early stopping applied using a patience of 25 epochs.

2.4. Evaluation Setup and Metrics

To evaluate the predictive performance of the models, three standard classification metrics were employed: Accuracy, F1-score, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC).

Train-validation-test protocol. All models were developed using a strict separation between training, validation, and testing data. The dataset was first split into a training subset (75%; 525 samples) and an independent test subset (25%; 176 samples). Only the training subset was used for model development, including preprocessing, standardization, hyperparameter selection, and early stopping. A stratified 5-fold cross-validation procedure was applied exclusively within the training subset. In each fold, 4/5 of the training data served as the inner training split, while 1/5 was used as the validation split for tuning and early stopping. No information from the test subset was used at any stage of model selection or parameter optimization.

After cross-validation, the final trained models were evaluated once on the independent test subset to obtain the final Accuracy, F1-score, and AUC metrics reported in the

Section 3. These test-set metrics represent the true generalization performance of each model, while the cross-validation metrics are used only for model selection and comparative analysis.

Accuracy quantifies the proportion of correctly classified samples among all predictions. While widely used, this metric may be less informative in the presence of class imbalance, as it does not account for the distribution of true positives and false negatives across individual classes [

25].

F1-score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced assessment of both false positives and false negatives. It is especially suitable when the cost of misclassification is asymmetric or when dealing with uneven class distributions, as in the case of fruit maturity stages [

25]. AUC measures the ability of the classifier to discriminate between classes, by computing the area under the ROC curve. It is threshold-independent and reflects the trade-off between the true positive rate and false positive rate across all decision thresholds. In multi-class settings, AUC is computed using a one-vs-rest approach and averaged across all classes [

26].

These metrics together offer a comprehensive evaluation of model performance, considering both classification correctness and class-wise discrimination capacity.

Cross-validation metrics (Accuracy, F1-score, AUC) reported in the tables represent the mean and standard deviation computed across the five validation folds within the training subset. These values quantify internal model stability and guide model selection, but they do not represent final model performance. Final test-set metrics were computed only once on the independent 176-sample test subset withheld from all stages of model development.

2.5. Main Experimental Design

The primary experiment was designed to evaluate model performance using only features obtained through non-destructive measurement techniques. This scenario reflects a practical application setting where fruit quality assessment must be performed without damaging the samples, such as in automated harvesting systems. For comparative analysis, models were also evaluated on the full feature set, which includes both non-destructive and destructive attributes. This comparison provides insight into the trade-off between prediction accuracy and measurement feasibility in real-world scenarios.

During the analysis, the iad (index of absorbance difference) variable emerged as a particularly strong predictor, frequently appearing as the top-ranked feature in model importance analyses. While iad is obtained non-destructively, it relies on specialized optical instrumentation that may not always be available in practical deployments. To assess the dependence of model performance on this variable, an additional experiment was performed under identical training and validation conditions, using a modified dataset excluding the iad feature. This allowed for the evaluation of predictive robustness in scenarios where simplified sensing configurations are required. Building on this, a final experiment was performed to identify a minimal yet powerful feature set, training the models using only the top-ranked predictors from the non-iad feature group. This aimed to define the most efficient model in terms of both predictive power and sensor complexity.

3. Results

The subsequent section presents the results of the conducted experiments, offering a comprehensive comparison of model performance across four distinct feature configurations. These configurations comprise: (1) training on the complete feature set, encompassing both destructive and non-destructive variables; (2) training exclusively on features derived from non-destructive methods; (3) training on the non-destructive subset following the exclusion of the iad variable; and (4) training on a select subset of top features from the non-destructive set, also excluding the iad variable. The primary objective of this analysis is to evaluate the predictive capacity of each model and to determine the impact of feature availability on classification performance.

Unless otherwise stated, all cross-validation performance values reported in this section correspond to the mean ± standard deviation across the five cross-validation folds, computed from predictions on the held-out validation partitions.

3.1. TabNet Evaluation

The TabNet model was trained using stratified 5-fold cross-validation on the selected feature subsets. Prior to cross-validation, a stratified 75/25 train-test split was applied, and the 5-fold procedure was conducted exclusively on the 525-sample training partition. After cross-validation, the model was retrained on the complete training subset and subsequently evaluated on the independent test set of 176 samples. The implementation was based on the pytorch_tabnet library, with training performed over a maximum of 200 epochs and early stopping (patience = 20). The implementation was based on the pytorch_tabnet library, with training performed over a maximum of 200 epochs and early stopping (patience = 20). The architecture consisted of 3 decision steps, 8-dimensional feature and attention transformers, and a batch size of 256. Optimization was carried out using the Adam optimizer with learning rate scheduling.

In addition to predicted class labels and probabilities, TabNet provides interpretable outputs in the form of feature selection masks, which capture the attention allocated to each input feature at every decision step. By aggregating these masks across folds and samples, global feature importance scores were derived.

Model performance for each fold was evaluated using Accuracy, F1-score, and AUC, and results were summarized in tabular format. Moreover, the averaged feature importance values were visualized as bar plots to highlight the most influential predictors across models and experimental conditions.

3.1.1. TabNet Model Evaluation Using the Full Feature Set

Using the full set of 43 predictors, the TabNet model showed stable performance across the validation folds. Cross-validation resulted in a mean accuracy of 0.8819 ± 0.0222, a mean AUC of 0.9344 ± 0.0138, and a mean F1-score of 0.8782 ± 0.0210.

Following cross-validation, the final model trained on the entire training subset was evaluated on the independent test set. The test results showed an accuracy of 0.8920, an F1-score of 0.8927, and an AUC of 0.9614, confirming strong generalization to unseen samples.

Feature importance analysis identified

iad as the most influential feature, followed by colourimetric and dielectric properties such as

moo_h,

moo_a_b, and

d_th. The corresponding feature importance plot, ROC curve, and learning curves are presented in

Figure 1a,

Figure 2, and

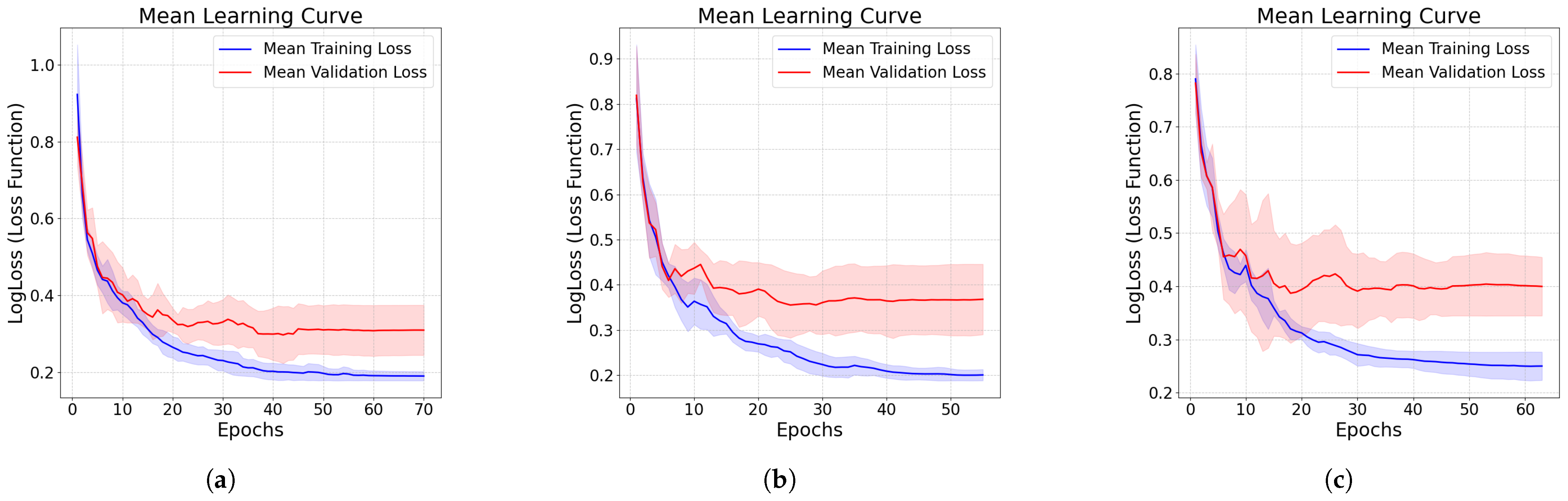

Figure 3a.

3.1.2. TabNet Model Evaluation Using Non-Destructive Features

Using the non-destructive feature set (38 features), the TabNet model achieved consistent results across validation folds, with a mean accuracy of 0.8819 ± 0.0214, a mean AUC of 0.9415 ± 0.0205, and a mean F1-score of 0.8774 ± 0.0222.

Evaluation on the independent test set resulted in an accuracy of 0.8977, an F1-score of 0.8941, and an AUC of 0.9528. These values confirm that the model generalizes well using only non-destructive measurements.

Feature importance analysis again highlighted

iad as the dominant predictor, together with colourimetric and dielectric features such as

moo_ccl,

moo_col, and

nd_zs_X. The corresponding visualizations are shown in

Figure 1b,

Figure 2, and

Figure 3b.

3.1.3. TabNet Performance on the Non-Destructive Set Without iad

Feature

For this feature subset, a stratified 75/25 train-test split was applied, with 5-fold cross-validation performed exclusively on the training portion (525 samples). After cross-validation, the model was retrained on the complete training set and evaluated on the independent test set (176 samples).

Cross-validation produced a mean accuracy of 0.8571, a mean F1-score of 0.8479, and a mean AUC of 0.8992. These values represent an expected decrease relative to the full non-destructive configuration, reflecting the removal of the highly influential iad variable.

Feature importance analysis showed that several non-destructive optical and dielectric properties remained strong predictors, including nd_zs, moo_a, moo_ccl, mass, and mop_a.

Evaluation on the independent test set yielded an accuracy of 0.8409, an F1-score of 0.8313, and an AUC of 0.9230. These metrics closely reflect the cross-validation performance and confirm that the reduced feature set remains capable of reliable maturity classification.

3.1.4. Optimized TabNet Model with Top-Performing Features

To investigate whether strong performance can be maintained using a more compact feature set, a series of experiments was conducted using only the highest-ranked non-destructive predictors (excluding iad). TabNet models were trained using progressively larger subsets of the most influential features, ranging from 9 to 15 variables.

The resulting test-set metrics are summarized in

Table 2. Performance did not improve monotonically with additional features; instead, a peak occurred at 13 features.

3.1.5. Comparative Analysis and Summary of TabNet Model Performance

A consolidated overview of the four TabNet configurations is presented in

Table 3. The comparison highlights the influence of feature selection on model performance based on test-set metrics.

To provide further insight into the predictive behaviour of the best-performing configuration (Non-Destructive Set), the corresponding confusion matrix on the independent test set is shown in

Table 4.

3.2. NODE Evaluation

The Neural Oblivious Decision Ensembles (NODE) model was trained using a stratified 5-fold cross-validation approach on the specified feature subsets. The implementation was based on the node-tabular library, with training performed for a maximum of 200 epochs and employing an early stopping mechanism with a patience of 25 epochs to prevent overfitting. The architecture consisted of an Oblivious Decision S-Tree (ODST) layer with 160 trees, each having a depth of 7, and a batch size of 256. Optimization was carried out using the Adam optimizer with a specified learning rate and weight decay.

To assess interpretability, global feature importance scores were derived post-hoc using a permutation-based method. After training on each fold, the importance of each feature was calculated by measuring the drop in model accuracy when that feature’s values were randomly shuffled. These scores were then averaged across all folds.

Model performance for each fold was evaluated using Accuracy, AUC, and F1-score, with the aggregated results summarized in tabular format. Furthermore, the averaged feature importance values were presented in tables to highlight the most influential predictors.

3.2.1. NODE Model Evaluation Using the Full Feature Set

This evaluation of the Neural Oblivious Decision Ensembles (NODE) model also utilizes the complete set of 43 predictor variables. This scenario provides a direct comparison to the TabNet model under identical data conditions, establishing a performance baseline with the full spectrum of available information.

A stratified 75/25 train-test split was applied, after which a 5-fold cross-validation procedure was conducted exclusively on the training portion (525 samples). The average performance across the 5-fold cross-validation indicates robust predictive capabilities, with a mean accuracy of 0.8590 ± 0.0244, a weighted F1-score of 0.8510 ± 0.0239, and a mean Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.9440 ± 0.0117. The standard deviations reflect consistent performance across folds.

Following cross-validation, the model was retrained on the full training set and subsequently evaluated on the independent test set (176 samples). The final test results showed an accuracy of 0.8636, an F1-score of 0.8588, and an AUC of 0.9496, confirming strong generalization to unseen data.

Feature importance was evaluated using the permutation importance method.

Figure 4a shows the ten most influential predictors. Consistent with the TabNet results, the

iad variable was identified as the dominant predictor, followed by color and dielectric properties such as

moo_b,

mop_cirg1, and

d_zs, although with substantially smaller contributions.

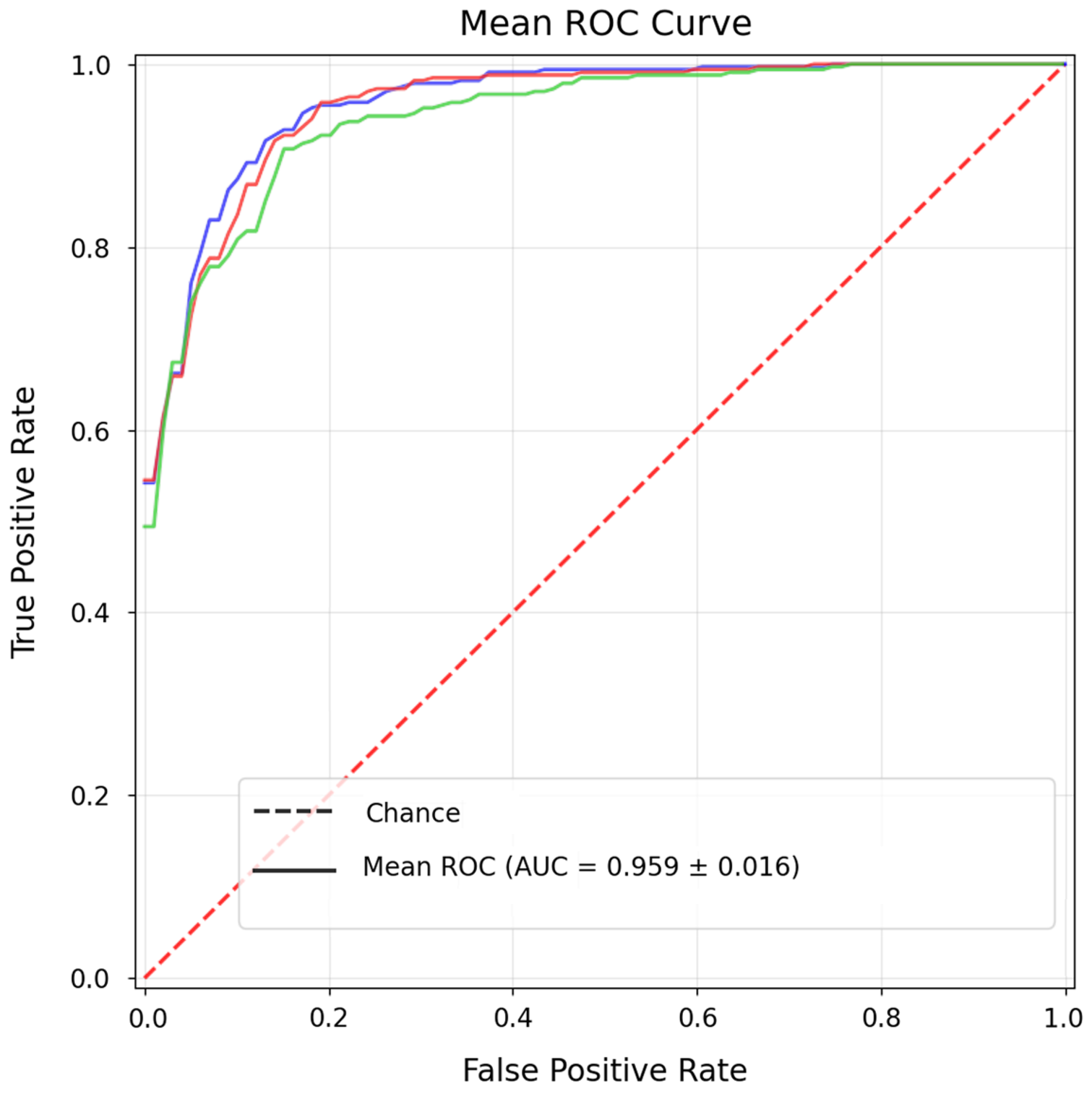

The model’s overall discriminative capability is illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6a. The mean receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve attained an average cross-validation AUC of 0.944, while the learning dynamics demonstrated stable convergence of training and validation losses, with early stopping effectively preventing overfitting across folds.

3.2.2. NODE Model Evaluation Using Non-Destructive Features

In this scenario, the NODE model was trained using a reduced feature set comprising 38 non-destructive variables. The purpose of this evaluation is to determine whether high predictive performance can be maintained when relying exclusively on measurements obtainable without physically altering or damaging the fruit, which is essential for real-world applications such as automated harvesting and in-field maturity estimation.

Across the 5-fold cross-validation, the model achieved a mean accuracy of 0.8667 ± 0.0217, a mean F1-score of 0.8575 ± 0.0205, and a mean AUC of 0.9369 ± 0.0127. These results demonstrate that the model retains strong predictive capability even without destructive measurements, performing at a level nearly equivalent to the full 43-feature configuration. The relatively small standard deviations indicate stable behaviour across folds, suggesting that the non-destructive feature set provides sufficiently rich and consistent information for reliable model training.

Permutation-based feature importance analysis (

Figure 4b) highlighted

iad as by far the most influential predictor, with a markedly higher importance score than any other feature. Following

iad, the most relevant variables were the dielectric properties

nd_zs and

nd_th, as colourimetric attributes such as

moo_b,

moo_c, and

udb. These findings are consistent with the structure uncovered by the TabNet model in the same experimental condition and reinforce the central role of dielectric and optical measurements in predicting peach maturity.

Evaluation on the independent test set yielded an accuracy of 0.8239, an F1-score of 0.8144, and an AUC of 0.9345. Although slightly lower than the cross-validation means, these values reflect solid generalisation and confirm that the model performs reliably when applied to unseen data. The observed difference between validation folds and the held-out test set is consistent with expectations for moderately sized datasets and does not indicate overfitting.

Overall, the results of this configuration demonstrate that the NODE model can achieve high discriminative performance while relying solely on non-destructive measurements, making this approach highly suitable for practical deployment scenarios. The ROC curve and learning behaviour for this configuration are presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6b.

3.2.3. NODE Model Evaluation Using Non-Destructive Features Without iad

This experimental scenario investigates the ability of the NODE model to perform maturity classification when the dominant iad variable is removed from the non-destructive feature set. The purpose of this analysis is twofold: (i) to quantify the extent to which the iad measurement contributes to the model’s discriminative performance, and (ii) to evaluate whether the remaining 37 non-destructive features contain sufficient information to support a reliable and practically usable classifier.

Across the 5-fold cross-validation, the model achieved a mean accuracy of 0.8457 ± 0.0258, a mean F1-score of 0.8341 ± 0.0248, and a mean AUC of 0.9294 ± 0.0157.

Although these metrics represent a noticeable decrease relative to the full non-destructive configuration that includes the iad feature, the overall reduction remains moderate. This confirms that several dielectric, and colourimetric measurements still encode meaningful discriminatory structure even in the absence of the most influential predictor. Interestingly, the slightly smaller standard deviations-particularly in accuracy-suggest improved fold-to-fold stability, indicating that the removal of iad may reduce sensitivity to sampling variability despite lowering the mean performance.

Permutation-based feature importance analysis (

Figure 4c) revealed a substantial reordering of the predictor hierarchy. With

iad removed, the dielectric properties

nd_zs and

nd_th emerged as the two most influential variables, followed by colourimetric attributes such as

moo_l,

moo_a,

moo_co, and

mop_cirg2. Additional contributors included physical traits such as

vol, as well as secondary colourimetric features (

moo_b,

moo_a_b). This ranking is consistent with the patterns observed in the TabNet analysis under the same feature constraints, reinforcing the robustness of these variables across modelling approaches.

Evaluation on the independent test set produced an accuracy of 0.8295, an F1-score of 0.8276, and an AUC of 0.9297. These results closely correspond to the cross-validation averages and demonstrate good generalisation to unseen samples. Despite the absence of the iad feature, the model retains a strong ability to distinguish between maturity classes.

Overall, while a decline in absolute performance is unavoidable when the dominant predictor is removed, the NODE model continues to exhibit stable and meaningful classification behaviour. This finding is relevant for practical deployments where

iad measurements may be unavailable, and it highlights the potential of the remaining non-destructive dielectric and colourimetric features to support autonomous maturity assessment systems. The ROC curve and learning dynamics for this configuration are presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6c.

3.2.4. Optimized NODE Model with Top-Performing Features

Following the removal of the iad feature, a final series of experiments was conducted to determine the optimal number of remaining non-destructive predictors required to maintain high model performance. The NODE architecture was trained on progressively larger subsets of the most influential features, starting from the top 9 and extending to the top 15. This procedure enabled the identification of the point at which additional features cease to improve predictive performance or introduce unnecessary noise.

The performance metrics for each configuration are summarized in

Table 5. For each subset, the model was evaluated using the independent test set following retraining on the full 525-sample training portion. This evaluation protocol ensures that the reported values reflect genuine generalization performance rather than cross-validation variability.

The results demonstrate that model performance remains relatively stable across subsets of 9–15 features, with only minor fluctuations in accuracy and F1-score. However, the configuration using 13 features achieves the highest test AUC (0.9227) and a competitive F1-score (0.8391), indicating the most effective balance between discriminative capability and model compactness.

This outcome suggests that enlarging the feature set beyond 13 variables offers no clear advantage, while smaller subsets occasionally reduce predictive strength. The 13-feature configuration therefore represents the optimal trade-off, retaining sufficient variability to support robust decision boundaries while avoiding the diminishing returns observed when additional features are included.

For completeness, the performance of this optimal 13-feature model is also highlighted separately in the overall NODE comparison presented in

Table 6.

3.2.5. Comparative Analysis and Summary of NODE Model Performance

This section synthesizes the results from the four experimental scenarios for the Neural Oblivious Decision Ensembles (NODE) model. A direct comparison, presented in

Table 6, provides an overview of the model’s behaviour under different feature availability constraints, based exclusively on the independent test set, in full alignment with the revised evaluation protocol.

The comparative analysis reveals several consistent trends. The full feature set yields the strongest overall performance across all evaluated configurations, with the highest AUC and a balanced combination of precision and recall. The non-destructive feature set produces slightly lower values but remains competitive, confirming that destructive measurements contribute little additional information for NODE.

Removing the dominant iad measurement results in an observable performance decline, consistent with findings from the TabNet experiments. Nevertheless, the model retains stable discriminative capability even without this feature. The optimized Top-13 feature configuration provides a compact alternative with competitive test-set performance, achieving the highest F1-score among the reduced-feature models.

To illustrate practical classification behaviour,

Table 7 presents the confusion matrix for the Top-13 Feature configuration evaluated on the independent test set.

3.3. SAINT Evaluation

The Self-Attention and Intersample Attention Transformer (SAINT) model was evaluated under the same revised protocol as the TabNet and NODE architectures. Following a stratified 75/25 train-test split, a 5-fold cross-validation procedure was applied exclusively to the training portion (525 samples), after which the model was retrained on the full training set and assessed on the independent test set (176 samples). This ensured a strictly controlled evaluation in which the final metrics reflect performance on data unseen during both model development and hyperparameter selection.

The model was implemented in a custom PyTorch (v2.7.1) framework and trained for up to 500 epochs, using early stopping (patience = 25) to prevent overfitting. The architecture employed a transformer dimension of 64, a depth of 6 attention layers, 8 attention heads, and a dropout rate of 0.05. Optimization was performed using AdamW (learning rate = 0.0001; weight decay = 0.01). To enhance generalization, CutMix augmentation (lambda = 0.1) was applied during training.

Since transformer-based architectures do not produce intrinsic feature importance, interpretability was addressed via a post-hoc Permutation Importance analysis, quantifying the reduction in validation accuracy when each feature was individually perturbed. Model performance across the four experimental feature configurations was evaluated using Accuracy, AUC, and F1-score, consistent with the other models in this study.

3.3.1. SAINT Model Evaluation Using the Full Feature Set

The initial evaluation of the Self-Attention and Intersample Attention Transformer (SAINT) model was conducted using the complete set of 43 predictor variables. As with the previous models, the revised evaluation protocol was applied: after the stratified 75/25 train-test split, a 5-fold cross-validation was performed exclusively on the training subset (525 samples), followed by retraining on the full training set and final testing on the independent test set (176 samples).

Across the cross-validation folds, the SAINT model achieved a mean accuracy of 0.8914, a mean AUC of 0.9552, and a mean F1-score of 0.8866. These results indicate strong and stable predictive performance, with low variability across folds (e.g., a standard deviation of approximately 0.02 for both accuracy and F1-score).

Model training was conducted using a custom PyTorch (v2.7.1) implementation for a maximum of 500 epochs, with an early stopping mechanism (patience = 25) based on validation loss. Optimization was performed using the AdamW optimizer (learning rate = 0.0001, weight decay = 0.01). The architecture consisted of a transformer dimension of 64, a depth of 6 layers, 8 attention heads, and a dropout rate of 0.05. In addition, CutMix augmentation (lambda = 0.1) was applied during training to improve generalization.

As the SAINT architecture does not yield intrinsic feature importance scores, a post-hoc interpretability analysis was performed using the Permutation Importance method. The average permutation scores-summarized in

Figure 7a—again identified the non-destructive

iad measurement as the most influential feature, followed by several additional non-destructive and destructive properties, including

nd_zs,

moo_a,

moo_h, and

ta. These results are consistent with the patterns observed in the other neural models.

The ROC and learning curves, shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9a, illustrate the high discriminative capacity and stable optimization behaviour of the SAINT model. The cross-validation mean ROC curve confirms a strong average AUC of 0.955, while the smooth convergence of the learning curves indicates effective regularization and the successful functioning of the early stopping mechanism.

Final evaluation on the independent test set yielded an accuracy of 0.8977, an AUC of 0.9735, and an F1-score of 0.9011. The confusion matrix shows balanced behaviour across the two classes, with only a small number of misclassifications. These results position SAINT as one of the top-performing models in this study when provided with the full combined destructive and non-destructive feature space.

3.3.2. SAINT Model Evaluation Using Non-Destructive Features

In the second scenario, the SAINT model was evaluated using a reduced set of 38 non-destructive features. This configuration is particularly relevant for practical, real-world deployments in which the fruit must remain intact, and the goal is to assess the extent to which the model can preserve high predictive performance without relying on destructive measurements.

Following the revised evaluation protocol, a stratified 75/25 train-test split was applied, and a 5-fold cross-validation was conducted exclusively on the training subset (525 samples). Across the validation folds, the model achieved a mean accuracy of 0.8876, a mean AUC of 0.9537, and a mean F1-score of 0.8831. These values are only slightly lower than those obtained with the full feature set, confirming that the non-destructive measurements encode nearly all of the discriminatory information required for reliable maturity classification.

The permutation-based feature importance analysis (

Figure 7b) again identified

iad as the dominant predictor, with a substantially higher importance score than any other variable. Secondary contributors included dielectric properties such as

nd_th and

nd_zs, followed by colourimetric attributes including

moo_a_b,

moo_a,

mop_l, and

moo_b. These findings align closely with the patterns observed for the TabNet and NODE models under the same experimental conditions.

The ROC and learning curves (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9b) further illustrate the model’s strong discriminative behaviour and stable optimization dynamics. The mean ROC curve confirms a high average AUC of approximately 0.954, while the learning curve demonstrates efficient convergence with effective regularization provided by CutMix and early stopping.

Final evaluation on the independent test set yielded an accuracy of 0.8864, an AUC of 0.9689, and an F1-score of 0.8913. The confusion matrix indicates balanced performance across both maturity classes, with only a small number of misclassifications. These results confirm that SAINT maintains strong generalization ability even when restricted to non-destructive measurements, making this configuration highly suitable for autonomous maturity assessment systems.

3.3.3. SAINT Model Evaluation Using Non-Destructive Features Without iad

This third experimental scenario evaluates the robustness of the SAINT architecture when its most influential predictor, the iad variable, is removed. This configuration is essential for assessing the standalone predictive value of the remaining 37 non-destructive features, which primarily consist of dielectric and colourimetric measurements. The results provide insight into the feasibility of practical, low-cost sensor systems that do not rely on the specialised instrumentation required for iad acquisition.

Following the revised protocol, a stratified 75/25 train-test split was applied, and a 5-fold cross-validation was performed exclusively on the training subset. Across the validation folds, the SAINT model achieved a mean accuracy of 0.8743, a mean AUC of 0.9428, and a mean F1-score of 0.8658. As expected, these values represent a moderate decline relative to the full non-destructive feature set, but the model nevertheless maintains strong discriminative performance, indicating that substantial predictive information remains available even without iad.

The feature-importance hierarchy (

Figure 7c) undergoes a clear reorganisation in the absence of

iad. Dielectric properties such as

nd_th and

nd_zs emerge as the dominant predictors, followed by several colour-related variables including

moo_ccl,

moo_b,

moo_col,

moo_c, and

moo_a. This pattern mirrors the shifts observed in the TabNet and NODE models under the same constraints, underscoring the consistent importance of optical and dielectric measurements.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9c illustrate that the overall discriminative capability remains high. The mean ROC curve confirms a robust average AUC of approximately 0.943, while the learning curves show stable convergence and effective regularisation.

Final evaluation on the independent test set yielded an accuracy of 0.8636, an AUC of 0.9594, and an F1-score of 0.8667. The confusion matrix indicates a well-balanced classification performance, with only a modest increase in misclassifications compared with the full non-destructive configuration. These findings demonstrate that SAINT remains a competitive model even without access to the iad measurement, highlighting the practical value of the remaining non-destructive features for autonomous maturity assessment systems.

3.3.4. Optimized SAINT Model with Top-Performing Features

In the final experimental stage, the SAINT model’s performance was evaluated on incrementally larger subsets of the most influential non-destructive features (after excluding iad). This analysis, conducted on feature sets ranging from 9 to 15 predictors, aimed to identify the optimal configuration that balances model complexity with predictive accuracy, simulating a cost-effective, targeted sensor system. As in the previous experiments, a stratified 75/25 train-test split was used, with 5-fold cross-validation performed exclusively on the 525-sample training subset and final evaluation on the independent test set of 176 samples.

The test-set performance metrics for each feature subset are summarized in

Table 8.

The results demonstrate the robustness of the SAINT architecture. Across all tested subsets from 9 to 15 features, test-set accuracy remains in a narrow range between 0.8352 and 0.8807, with F1-scores between 0.8415 and 0.8786 and all AUC values above 0.95. The configuration with 15 features achieves the highest test AUC (0.9607), together with the joint-best test accuracy (0.8807) and F1-score (0.8786), and is therefore selected as the optimal trade-off between model compactness and predictive performance.

The permutation importance analysis identified a set of fifteen non-destructive variables as the most informative predictors for the SAINT model. For clarity of presentation,

Figure 7c displays only the ten highest-ranked features; however, these correspond closely to the top part of the full fifteen-feature ranking used during model optimization.

The performance metrics obtained using the complete optimized subset of fifteen features (excluding

iad) are also included in the overall SAINT comparison presented in

Table 9.

3.3.5. Comparative Analysis and Summary of SAINT Model Performance

This section consolidates the independent test-set results for all SAINT configurations. The full feature set is included exclusively as an upper-bound reference and is not considered for operational deployment. Among the reduced-feature models, the configuration based on the top-performing fifteen non-destructive features offers the most balanced trade-off between predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and system simplicity, and is therefore highlighted as the preferred solution.

Although the full feature configuration achieves the highest absolute performance, the differences between it and the reduced models remain relatively modest. For practical deployment-particularly in real-time or embedded contexts-the complexity, sensor requirements, and computational overhead become equally important considerations.

The top-performance subset of fifteen features delivers slightly lower accuracy and F1-score compared with the full non-destructive set; however, it provides a markedly more efficient and lightweight architecture. This configuration reduces the dimensionality by over 60%, eliminates reliance on destructive measurements, and requires only a compact set of inexpensive sensors. It also trains faster, converges more consistently across folds, and exhibits excellent generalization on the independent test set. These properties make it the most attractive configuration for realistic, resource-constrained maturity prediction systems.

A class-wise evaluation for the selected top-performing model is provided in

Table 10.

4. Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the performance of three modern neural network architectures; TabNet, NODE, and SAINT, for the non-destructive classification of peach maturity. Our findings align with a growing body of literature that positions neural networks and machine learning as state-of-the-art tools for fruit quality assessment. The superiority of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) over traditional models has been decisively shown; for instance, Abdel-Sattar et al. [

27] demonstrated that an ANN achieved an R

2 greater than 0.97 for predicting peach quality attributes, while regression models struggled. Similarly, a study by Kangune et al. [

28] showed a CNN model achieving significantly higher accuracy (79.49%) compared to an SVM model (69%) for grape ripeness, which supports our decision to focus exclusively on neural architectures.

The performance of our models is highly competitive, especially when compared to studies on the same ‘Redhaven’ cultivar. Scalisi et al. [

29] used a fluorescence spectrometer on ‘Redhaven’ peaches and achieved a pooled F1-score of 0.85 for classifying maturity. In our study, the optimized SAINT model using 15 non-destructive top features achieved an F1-score of 0.8786, while the optimized TabNet model using 13 features achieved an F1-score of 0.8623. These results demonstrate that compact, potentially lower-cost sensor configurations combined with specialized tabular neural networks can match or exceed the performance of more complex spectrometric approaches. While modern CNNs achieve high accuracies on image data, often exceeding 96% for bananas [

30] or 94% for plums in uncontrolled environments [

31], our study highlights that high accuracy is also attainable using less expensive, non-image, tabular data. This modernizes earlier approaches, such as that of Llobet et al. [

32], who used an electronic nose and neural networks to achieve over 90% accuracy for banana ripeness. Our work contributes to this field by applying the latest architectures specifically designed for the tabular data that such sensor systems produce.

Beyond direct maturity sensing, the utility of machine learning in peach orchards is well-established for modeling complex agricultural systems. Studies have successfully used ANNs to predict fruit quality from soil mineral content [

33] and Random Forest models to diagnose tree nutrition with over 80% accuracy [

34], underscoring the power of these methods to handle intricate, non-linear interactions. The final comparative analysis of our models, presented in

Table 11, further explores these capabilities.

A consolidated view of the results shows that no single model dominates in all scenarios; rather, each architecture performs best under specific conditions. The SAINT model consistently achieved the highest scores when the dataset included the full feature set, which is in line with its design that leverages attention mechanisms to model interactions between features.

In contrast, when relying entirely on the comprehensive non-destructive feature set (38 features), the TabNet model delivered the strongest overall performance (Accuracy = 0.8977; F1 = 0.8941), surpassing both NODE and SAINT in this practically relevant scenario. This indicates that TabNet’s sequential attention mechanism is particularly effective when a full collection of low-cost non-destructive measurements is available.

In the reduced-feature settings, the optimized SAINT configuration using 15 features provided the strongest overall performance (Accuracy = 0.8807; F1 = 0.8786). However, the 13-feature TabNet configuration (Accuracy = 0.8693; F1 = 0.8623) remained highly competitive, offering a favorable balance of accuracy, robustness, and interpretability.

All three models exhibit a measurable decline once the iad variable is removed, confirming its relevance for maturity prediction. Nevertheless, the optimized configurations—particularly the 13-feature TabNet and 15-feature SAINT models—demonstrate that reliable classification is achievable using compact, non-destructive feature subsets, which is important for practical implementation.

The practical implications of our research are best viewed in the context of large-scale precision agriculture. As demonstrated by Zhang et al. [

35] for almond yield prediction, machine learning models are essential tools for orchard-level management. Our conclusion regarding the practicality of compact, optimized models resonates with the findings of Mazen and Nashat [

36], who also highlighted the importance of feature selection for achieving high performance in banana classification. This confirms that the future of practical systems lies not only in model complexity but in the synergy between an optimized architecture and a minimal, yet informative, set of low-cost sensor data, offering a tangible pathway towards robust and scalable systems for real-time decision support.

4.1. Limitations of the Study

Despite the robust findings, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, all models were trained and validated exclusively on the ‘Redhaven’ peach cultivar. The physiological and spectral properties can vary significantly between different cultivars, and further research is needed to validate the model’s generalizability. Second, the data were collected from a single geographical location and season, meaning the models might not account for variations caused by different climatic conditions or horticultural practices. Finally, while the dataset of 701 samples is comprehensive for this type of agricultural study, it is relatively small by deep learning standards, which could limit the models from learning even more complex patterns. Although the dataset is relatively small by deep learning standards, the study employed a stratified 75/25 train-test split combined with 5-fold cross-validation performed exclusively on the training subset. Future research should validate the models on external datasets from additional seasons and cultivars.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Based on these limitations, several avenues for future research emerge. A crucial next step is to evaluate the performance of the optimized TabNet and SAINT models on a multi-cultivar dataset collected across different seasons and locations. Another promising direction is the development and field-testing of a prototype sensor system based on the 13 optimal non-destructive features. This would involve integrating the required sensors into a portable unit or an autonomous platform to validate the model’s performance in real-time. Finally, exploring data fusion techniques that combine these tabular features with low-resolution multispectral images could potentially unlock further performance gains.

4.3. Model Interpretability and Explainability

From the perspective of interpretability, all three models provided valuable insights into the underlying feature relevance. TabNet, by design, offers inherent interpretability through its sequential attention mechanism, which highlights the contribution of each feature at every decision step. This allowed visualization of feature importance dynamics and identification of the most influential attributes contributing to classification decisions. For the SAINT and NODE models, which are less interpretable by nature, post hoc permutation-based analysis was performed, revealing a high degree of consistency in the ranking of dominant predictors. In particular, dielectric properties and ground color-based features frequently appeared among the top-ranked variables, confirming their physiological relevance to fruit maturity. The concordance across different model architectures suggests that the observed feature relationships are robust and not driven by random correlations or overfitting effects.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated the high potential of modern neural network architectures for non-destructive classification of peach maturity using tabular sensor data. Through a systematic evaluation of TabNet, NODE, and SAINT models across four distinct feature configurations, we have shown that it is possible to achieve high classification accuracy (up to 89.77%) without resorting to destructive measurement techniques.

The key findings are threefold:

The transformer-based SAINT architecture exhibited the highest overall predictive performance when the full feature set (43 variables) was available, achieving an F1-score of 0.9011 and an AUC of 0.9735, and thus establishing the upper benchmark for this dataset.

The iad index was confirmed as the single most influential predictor of maturity. However, all models demonstrated the capacity to maintain strong performance even in its absence, relying on a combination of dielectric, colorimetric, and morphometric features.

The TabNet model, when optimized to use only the top 13 non-destructive features (excluding iad), emerged as a highly practical and well-balanced solution. It achieved an accuracy of 86.93% and an F1-score of 0.8623, offering a compelling balance of performance, efficiency, and interpretability for real-world deployment.

These results suggest that future research should focus on deploying such optimized, low-cost sensor systems in real-world agricultural settings. The integration of a model like the 13-feature TabNet into autonomous platforms could significantly enhance the efficiency of selective harvesting, improve fruit quality management, and reduce post-harvest losses, thereby contributing to more sustainable and profitable horticultural practices.

A crucial next step will be to evaluate the performance of the optimized TabNet and SAINT models on a multi-cultivar dataset collected across different seasons and locations. Additionally, future efforts should explore the development of a prototype sensor system based on the 13 optimal features, integrating the required sensors into a portable or autonomous platform to validate the model’s performance in real time. Finally, exploring data fusion techniques that combine these tabular features with low-resolution multispectral imaging may further enhance predictive accuracy and interpretability.