Radiotherapy for Liver-Confined Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Elderly Patients with Comorbidity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

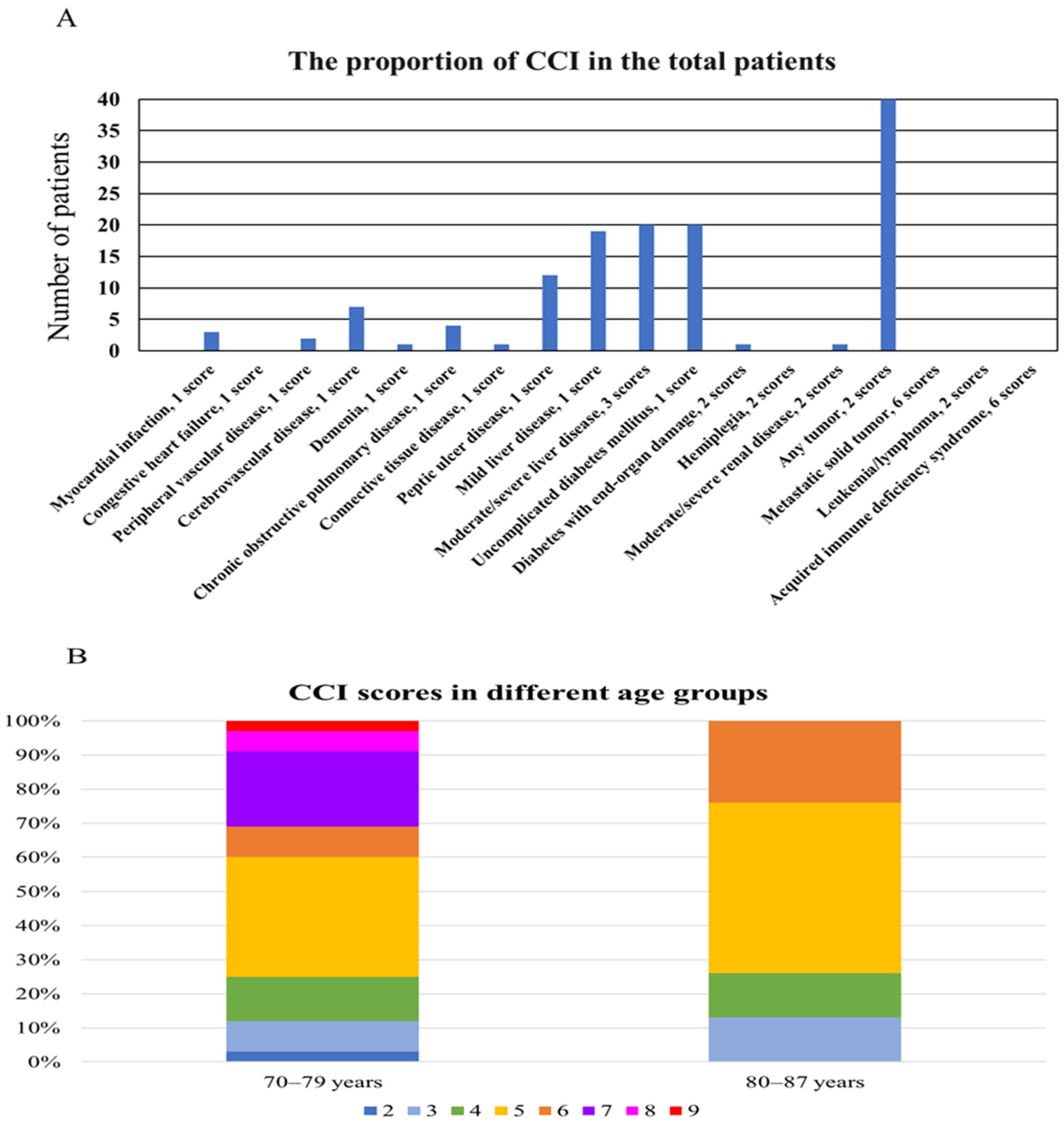

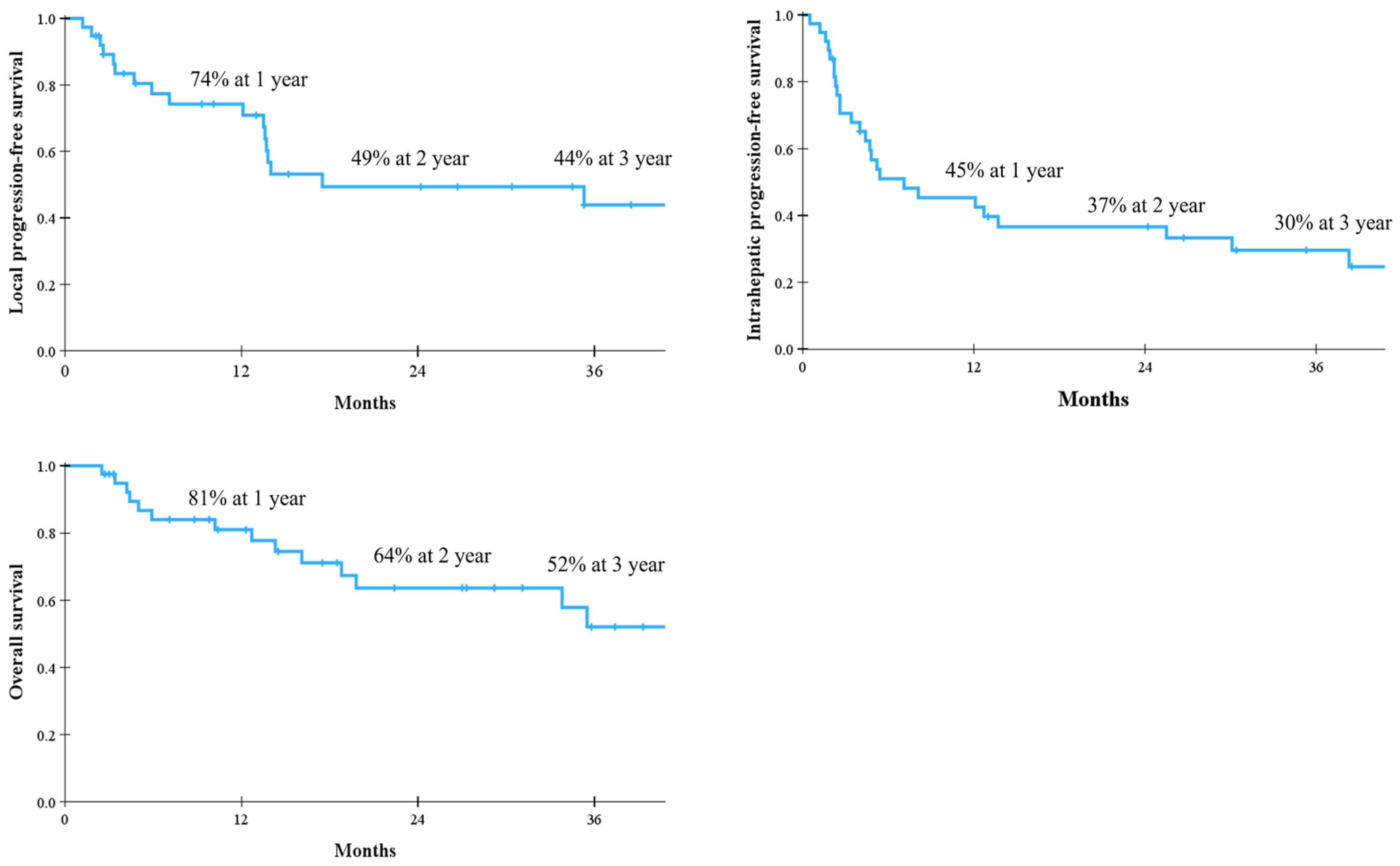

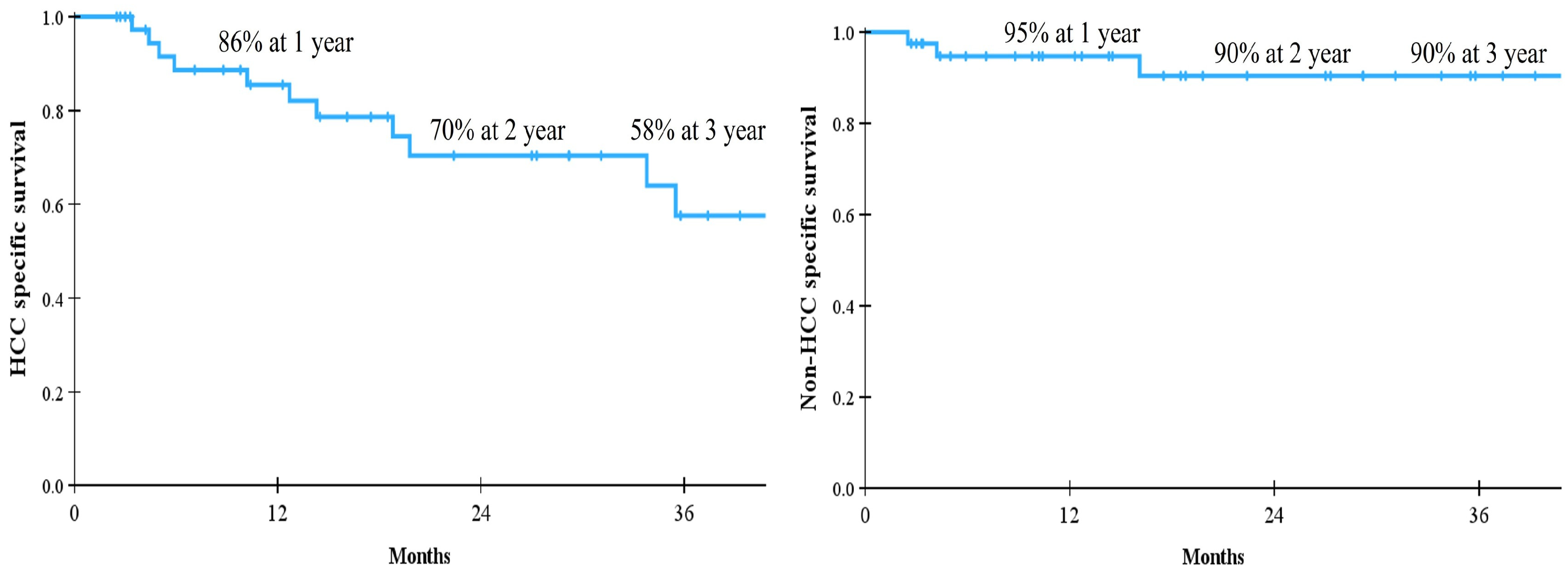

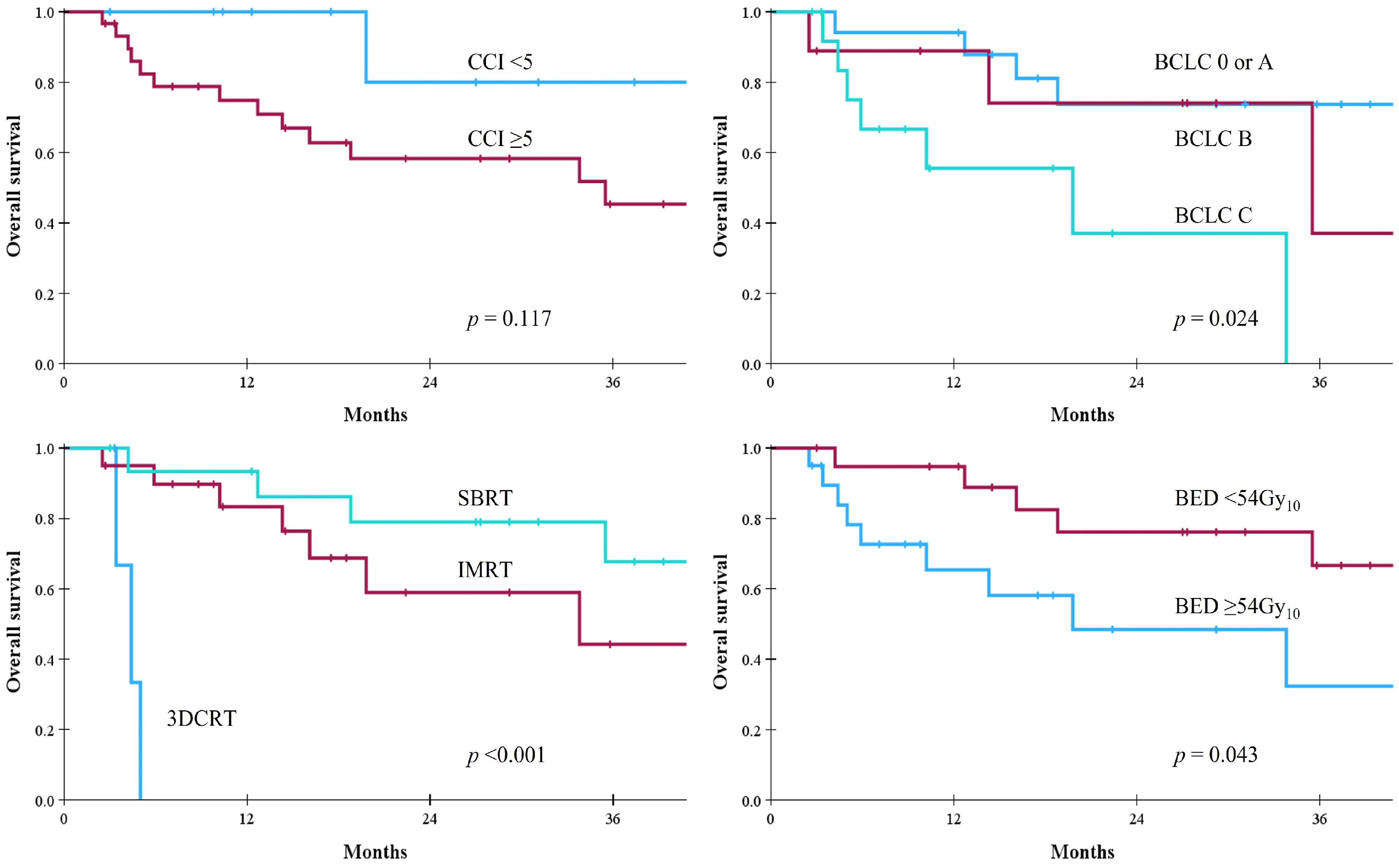

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Pan, G.; Guan, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, W.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Ouyang, G. The burden of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies from 1990 to 2019 at the global, regional, and national levels. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1160–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzio, M.; Dionigi, E.; Parisi, G.; Raguzzi, I.; Sacco, R. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Weng, Z.; Zhou, S.; Feng, L.; Qin, Z.; Ma, D. Global burden and regional inequalities of cancer in older adults from 1990 to 2021 and its projection until 2050. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, M.; Tanaka, M.; Ando, E.; Sakata, M.; Shimose, S.; Ohno, M.; Yutani, S.; Kuraoka, K.; Kuromatsu, R.; Sumie, S.; et al. Long-term outcome of elderly patients (75 years or older) with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2014, 44, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukioka, G.; Kakizaki, S.; Sohara, N.; Sato, K.; Takagi, H.; Arai, H.; Abe, T.; Toyoda, M.; Katakai, K.; Kojima, A.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in extremely elderly patients: An analysis of clinical characteristics, prognosis and patient survival. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Cho, J.Y.; Kim, E.; Na, H.Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, N.R.; Yoon, Y.I.; Lee, B.; Jang, E.S.; Jung, Y.K.; et al. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: An expert consensus-based practical recommendation from the Korean Liver Cancer Association. J. Liver Cancer 2025, 25, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Cho, E.; Jun, C.H.; Park, S.Y.; Cho, S.B.; Park, C.H.; Kim, H.S.; Choi, S.K.; Rew, J.S. Characteristics and Outcomes of Extreme Elderly Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma in South Korea. In Vivo 2019, 33, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyder, O.; Dodson, R.M.; Nathan, H.; Herman, J.M.; Cosgrove, D.; Kamel, I.; Geschwind, J.F.; Pawlik, T.M. Referral patterns and treatment choices for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A United States population-based study. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 217, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunot, A.; Le Sourd, S.; Pracht, M.; Edeline, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients: Challenges and solutions. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2016, 3, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkawa, H.; Tanaka, S.; Takemura, S.; Amano, R.; Kimura, K.; Nishioka, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Kubo, S. Predictive Value of the Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index for Outcomes After Hepatic Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 3901–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, G.; Yang, X.; Wan, W.H. The Age-Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index Predicts Prognosis in Elderly Cancer Patients. Cancer Manag. Res. 2022, 14, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Morris, L.; Ludmir, E.B.; Movsas, B.; Jagsi, R.; VanderWalde, N.A. Radiation Therapy in Older Adults With Cancer: A Critical Modality in Geriatric Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1806–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apisarnthanarax, S.; Barry, A.; Cao, M.; Czito, B.; DeMatteo, R.; Drinane, M.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Koay, E.J.; Lasley, F.; Meyer, J.; et al. External Beam Radiation Therapy for Primary Liver Cancers: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 12, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.I.; Jo, S.; Moon, J.E.; Bae, S.H.; Park, H.C. The Current Evidence of Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Chun, S.J.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, E.; Kang, J.K.; Jang, W.I.; Moon, J.E.; Roquette, I.; Mirabel, X.; Kimura, T.; et al. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Meta-Analysis and International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society Practice Guidelines. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 118, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.H.; Jang, W.I.; Mortensen, H.R.; Weber, B.; Kim, M.S.; Hoyer, M. Recent update of proton beam therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Liver Cancer 2024, 24, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Sanduzzi-Zamparelli, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fabrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, A.; Diaz, A.; Llarch, N.; Iserte, G.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendations: The 2025 update. J. Hepatol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, B.K.; Yu, J.I.; Park, H.C.; Goh, M.J.; Paik, Y.H. Radiotherapy trend in elderly hepatocellular carcinoma: Retrospective analysis of patients diagnosed between 2005 and 2017. Radiat. Oncol. J. 2023, 41, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Kim, M.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Lim, Y.H.; Bae, H.J.; Kim, D.K.; Park, J.Y.; Noh, J.; Lee, J.P. Recalibration and validation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index in an Asian population: The National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternby Eilard, M.; Helmersson, M.; Rizell, M.; Vaz, J.; Aberg, F.; Taflin, H. Non-liver comorbidity in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and curative treatments—A Swedish national registry study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 60, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.G.; Yoo, J.J.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, M.H.; Lim, S.; Jung, J.H.; Lim, S.H. Treatment outcomes of helical tomotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma in terms of intermediate-dose spillage. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1420–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Cho, K.H.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.G.; Yoo, J.J.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, M.H.; Jung, J.H.; Lim, S.H. Stereotactic body radiotherapy using helical tomotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Clinical outcome and dosimetric comparison of Hi-ART vs. Radixact. Transl. Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 3964–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wu, T.; Lu, Q.; Dong, J.; Ren, Y.F.; Nan, K.J.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, X.F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly: Clinical characteristics, treatments and outcomes compared with younger adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.A.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.L.; Song, J.E.; Lee, D.H.; Han, S.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, B.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Rhim, H.; et al. The efficacy of treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients. J. Liver Cancer 2023, 23, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Cho, H.A.; Jun, C.H.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, S.B.; Choi, S.K. A Review of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Elderly Patients Focused on Management and Outcomes. In Vivo 2019, 33, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, J.A.; Fontana, R.J.; Su, G.L.; Conjeevaram, H.S.; Emick, D.M.; Lok, A.S. NAFLD may be a common underlying liver disease in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology 2002, 36, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.W.; Sohn, W.; Choi, G.H.; Jang, J.W.; Seo, G.H.; Kim, B.H.; Choi, J.Y. Evolving trends in treatment patterns for hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea from 2008 to 2022: A nationwide population-based study. J. Liver Cancer 2024, 24, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Xian, Y.; Dale, W.; Fisher, S.G.; Rodin, M.; Morrow, G.R.; Neugut, A.; Hall, W. Association of a cancer diagnosis with vulnerability and frailty in older Medicare beneficiaries. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, M.; Tokuuye, K.; Sugahara, S.; Tohno, E.; Nakayama, H.; Fukumitsu, N.; Mizumoto, M.; Abei, M.; Shoda, J.; Minami, M.; et al. Proton beam therapy for aged patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 69, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, S.; Abe, T.; Shibuya, K.; Katoh, H.; Koyama, Y.; Shimada, H.; Kakizaki, S.; Shirabe, K.; Kuwano, H.; Ohno, T.; et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy for 80 years or older patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraoka, Y.; Kimura, T.; Aikata, H.; Daijo, K.; Osawa, M.; Honda, F.; Nakamura, Y.; Morio, K.; Morio, R.; Hatooka, M.; et al. Clinical outcomes of stereotactic body radiotherapy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2018, 48, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, H.; Ogino, H.; Hattori, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Nomura, K.; Hayashi, K.; Toshito, T.; Sasaki, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Mizoe, J.E.; et al. Image-Guided Proton Therapy for Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: High Local Control and Quality of Life Preservation. Cancers 2021, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, M.; Comito, T.; Franzese, C.; Desideri, I.; Dominici, L.; Lo Faro, L.; Clerici, E.; Franceschini, D.; Baldaccini, D.; Badalamenti, M.; et al. Charlson comorbidity index and G8 in older old adult (≥80 years) hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.Y.; Jung, J.; Lee, D.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Lim, Y.S.; Lee, H.C.; Park, J.H.; Yoon, S.M. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for elderly patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective observational study. J. Liver Cancer 2022, 22, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Meena, B.L.; Anju, K.V.; Jagya, D.; Sarin, S.K.; Yadav, H.P. Efficacy and safety of stereotactic body radiation therapy in elderly patients with cirrhosis and large advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2025, 21, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, P.; Chuong, M.D.; Schaub, S.K.; Lo, S.S.; Ibrahim, M.; Apisarnthanarax, S. Proton Beam Therapy and Photon-Based Magnetic Resonance Image-Guided Radiation Therapy: The Next Frontiers of Radiation Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 22, 15330338231206335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirokawa, F.; Hayashi, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Asakuma, M.; Shimizu, T.; Komeda, K.; Inoue, Y.; Takeshita, A.; Shibayama, Y.; Uchiyama, K. Surgical outcomes and clinical characteristics of elderly patients undergoing curative hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2013, 17, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.M.; Chen, Z.X.; Ma, P.C.; Chen, J.M.; Jiang, D.; Hu, X.Y.; Ma, F.X.; Hou, H.; Ma, J.L.; Geng, X.P.; et al. Oncological prognosis and morbidity of hepatectomy in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score matching and multicentre study. BMC Surg. 2023, 23, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagihara, T.K.; Tepper, J.E.; Moon, A.M.; Barry, A.; Molla, M.; Seong, J.; Torres, F.; Apisarnthanarax, S.; Buckstein, M.; Cardenes, H.; et al. Defining Minimum Treatment Parameters of Ablative Radiation Therapy in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Expert Consensus. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 14, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keall, P.J.; Mageras, G.S.; Balter, J.M.; Emery, R.S.; Forster, K.M.; Jiang, S.B.; Kapatoes, J.M.; Low, D.A.; Murphy, M.J.; Murray, B.R.; et al. The management of respiratory motion in radiation oncology report of AAPM Task Group 76. Med. Phys. 2006, 33, 3874–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellera, C.A.; Rainfray, M.; Mathoulin-Pelissier, S.; Mertens, C.; Delva, F.; Fonck, M.; Soubeyran, P.L. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extermann, M. Measuring comorbidity in older cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2000, 36, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | Condition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, peptic ulcer disease, mild liver disease a, uncomplicated diabetes mellitus |

| 2 | Hemiplegia, moderate to severe renal disease, diabetes with end-organ damage, any tumor, leukemia, lymphoma |

| 3 | Moderate/severe liver disease b |

| 6 | Metastatic solid tumor, acquired immune deficiency syndrome |

| Parameters | No. of Patients | Parameters | No. of Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median 75 years (70–87 years) | Baseline CP class | A | 34 (85%) | |

| Sex | Male | 28 (70%) | B | 6 (15%) | |

| Female | 12 (30%) | BCLC stage | 0 | 7 (17%) | |

| CCI | Median 5 (2–9) | A | 10 (25%) | ||

| ACCI | Median 8 (5–11) | B | 9 (23%) | ||

| CCI-P | Median 2 (0–6) | C | 14 (35%) | ||

| Viral hepatitis | No | 18 (45%) | PVTT | No | 27 (68%) |

| HBV | 17 (43%) | Yes | 13 (32%) | ||

| HCV | 4 (10%) | Combined treatment | No | 27 (68%) | |

| HBV/HCV | 1 (2%) | Yes | 13 (32%) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | No | 9 (23%) | RT aim | Radical intent | 30 (75%) |

| Yes | 31 (77%) | Palliative intent | 10 (25%) | ||

| Previous treatment | No | 14 (35%) | RT technique | 3DCRT | 4 (10%) |

| Yes | 26 (65%) | IMRT | 20 (50%) | ||

| Type of previous treatment | Surgery | 11 (28%) (1–2 cycles) | SBRT | 16 (40%) | |

| RFA | 3 (8%) (1–2 cycles) | GTV | Median 32.7 cc (2.3–1241.8 cc) | ||

| TACE | 23 (57%) (1–16 cycles) | PTV | Median 143.8 cc (17.8–1818.0 cc) | ||

| RT | 1 (2%) | Fraction size | Median 3.2 Gy (1.8–14.0 Gy) | ||

| Sorafenib | 1 (2%) | Total dose | Median 44 Gy (30–60 Gy) | ||

| Ate/beva | 1 (2%) | BED | Median 55.6 Gy10 (39.0–134.4 Gy10) | ||

| Parameters | 1Y LPFS | 3Y LPFS | p-Value | 1Y IHPFS | 3Y IHPFS | p-Value | 1Y OS | 3Y OS | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <80 years | 72% | 41% | 0.509 | 41% | 26% | 0.284 | 79% | 54% | 0.907 |

| ≥80 years | 83% | 63% | 67% | 50% | 88% | 37% | ||||

| Sex | Male | 70% | 38% | 0.140 | 37% | 24% | 0.126 | 76% | 64% | 0.704 |

| Female | 82% | 58% | 64% | 41% | 92% | 43% | ||||

| CCI | <5 | 89% | 59% | 0.513 | 40% | 40% | 0.905 | 100% | 80% | 0.117 |

| ≥5 | 69% | 39% | 47% | 25% | 75% | 45% | ||||

| Baseline CP class | A | 79% | 49% | 0.011 | 51% | 33% | 0.014 | 84% | 56% | 0.066 |

| B | 44% | 0% | 17% | - | 60% | - | ||||

| BCLC stage | O/A | 94% | 86% | <0.001 | 74% | 58% | <0.001 | 94% | 74% | 0.024 |

| B | 86% | 21% | 51% | 25% | 89% | 37% | ||||

| C | 41% | 0% | 8% | 0% | 56% | 0% | ||||

| PVTT | No | 92% | 63% | <0.001 | 63% | 44% | <0.001 | 92% | 67% | 0.005 |

| Yes | 35% | 0% | 8% | 0% | 51% | 0% | ||||

| RT aim | Radical | 89% | 55% | <0.001 | 58% | 38% | <0.001 | 93% | 59% | 0.001 |

| Palliative | 26% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 26% | - | ||||

| RT technique | 3DCRT | - | - | <0.001 | 0% | 0% | <0.001 | 0% | 0% | <0.001 |

| IMRT | 66% | 22% | 39% | 14% | 83% | 44% | ||||

| SBRT | 93% | 73% | 61% | 53% | 93% | 68% | ||||

| BED | <54 Gy10 | 53% | 13% | <0.001 | 28% | 11% | 0.002 | 65% | 32% | 0.043 |

| ≥54 Gy10 | 94% | 75% | 62% | 47% | 95% | 7% |

| Authors (Year) | Age (Years) (Median) | No. of Pts | Indication | RT Technique | Median RT Dose (Gy) (Range) | No. of Fractions | LPFS | PFS | OS | RILD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hata [35] (2007) | 80–85 (81) | 21 | UICC T1 or T3 | PBT | 66 (60–70) | 10–35 | 100% at 1Y | 70% at 1Y | 84% at 1Y | 0% |

| 100% at 3Y | 51% at 3Y | 62% at 3Y | ||||||||

| Shiba [36] (2017) | 80–95 (83) | 31 | BCLC A–C | CIRT | 60 (52.8 or 60) | 4 or 12 | 89% at 2Y | 51% at 2Y | 82% at 2Y | 3% |

| Teraoka [37] (2018) | 75–93 (79) | 54 | ≤3 HCCs ≤ 3 cm, MVI (-) | SBRT | 48 (40, 48, 60) | 4 or 8 | 100% at 1Y | 51% at 1Y | 96% at 1Y | NR |

| 98% at 3Y | 27% at 3Y | 64% at 3Y | ||||||||

| Iwata [38] (2021) | 80–96 (82) | 71 | BCLC 0–D | PBT | 66 (66 or 72.6) | 10 or 22 | 88% at 2Y | 50% at 2Y | 76% at 2Y | 0% |

| Loi [39] (2021) | 80–91 (85) | 42 | BCLC A or B | SBRT | 54 (30–75) | 3–10 | 93% at 1Y | 47% at 1Y | 72% at 1Y | 0% |

| 93% at 2Y | 31% at 2Y | 43% at 2Y | ||||||||

| Jang [40] (2022) | 75–90 (77) | 83 | ≤2 HCCs ≤ 6 cm, MVI (-) | SBRT | 45 (36–60) | 3–4 | 98% at 3Y | 30% at 3Y a | 57% at 3Y | NR |

| 90% at 5Y | 10% at 5Y a | 41% at 5Y | ||||||||

| Sharma [41] (2025) | 70–84 (75) | 24 | BCLC C | SBRT | 35 (25–40) | 5 | 90% at 1Y | 42% at 1Y | 58% at 1Y | 0% |

| Current study | 70–87 (75) | 40 | BCLC 0–C | Overall | 44 (30–60) | 4–25 | 74% at 1Y | 45% at 3Y a | 81% at 1Y | 2% |

| 44% at 3Y | 30% at 3Y a | 52% at 3Y | ||||||||

| 3DCRT | 37.5 (30 or 45) | 10 or 25 | - | 0% at 3Y a | 0% at 3Y | |||||

| IMRT | 44 (30–60) | 10–25 | 22% at 3Y | 14% at 3Y a | 44% at 3Y | |||||

| SBRT | 48 (32–56) | 4 | 73% at 3Y | 53% at 3Y a | 68% at 3Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bae, S.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, S.G.; Yoo, J.-J.; Lee, J.M.; Lim, S.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, C.K. Radiotherapy for Liver-Confined Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Elderly Patients with Comorbidity. Cancers 2026, 18, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010091

Bae SH, Kim YS, Kim SG, Yoo J-J, Lee JM, Lim S, Jung JH, Kim CK. Radiotherapy for Liver-Confined Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Elderly Patients with Comorbidity. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleBae, Sun Hyun, Young Seok Kim, Sang Gyune Kim, Jeong-Ju Yoo, Jae Myeong Lee, Sanghyeok Lim, Jae Hong Jung, and Chan Kyu Kim. 2026. "Radiotherapy for Liver-Confined Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Elderly Patients with Comorbidity" Cancers 18, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010091

APA StyleBae, S. H., Kim, Y. S., Kim, S. G., Yoo, J.-J., Lee, J. M., Lim, S., Jung, J. H., & Kim, C. K. (2026). Radiotherapy for Liver-Confined Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Elderly Patients with Comorbidity. Cancers, 18(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010091